Caesarius von Heisterbach

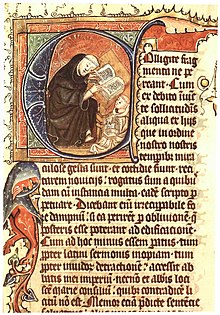

Caesarius von Heisterbach (* around 1180 in or near Cologne , † after 1240 in Heisterbach) was an educated Cistercian monk and novice master in the Cistercian monastery Heisterbach near Königswinter .

As a famous Cologne chronicler, author of church writings and narrator, he collected stories of the miracles and visions of his time in Dialogus miraculorum (1219–1223) , as another title of this work says: De miraculis et visionibus sui temporis . His second collection of copies, VIII libri miraculorum (“Eight Books of Miracles”) also contains stories that are valuable for the history of customs and culture. His Engelbert biography Vita, passio et miracula beati Engelberti Coloniensis archiepiscopi is the chronicle of the life and death of the murdered Archbishop Engelbert I of Cologne . He also wrote the Vita s. Elisabeth (1236–1237) about St. Elisabeth of Thuringia .

Life

Caesarius von Heisterbach is attested in Cologne for the years 1188 to 1198. He attended the school of St. Andreasstift , which was under the supervision of Dean Ensfried, to whom Caesarius grants a long chapter in his Dialogus miraculorum . There he describes him as a “man of a long standing” (“vir magni nominis”) and describes him as a benevolent, pious-naive, brave man.

During this time, Caesarius was still a little student ("adhuc scholaris parvulus"), he suffered a serious illness that was cured by a sweat bath.

After his time at St. Andreasstift, Caesarius attended the cathedral school, where he received his theological training from the famous cathedral scholasticus Rudolf, who had previously taught in Paris.

Caesarius later wrote numerous “sermon tales” that are often set in Cologne. These reveal details of his stay in Cologne. So he ran as a schoolboy with his comrades to the place of execution at the gates of the city. He heard mass in Michael's Basilica. He often stayed on Hoch- and Schmalgasse ("Strata Alta et Angusta"), and he also experienced the miracle on the cross in St. George's Church . One afternoon in 1198 he stayed with others in the archiepiscopal palace to see the shining star wonder.

In October 1198 Caesarius migrated from the monastery in Walberberg to Cologne with Gevard, the second abbot of the Cistercian Abbey of Heisterbach, which is located near Bonn in the Siebengebirge . Gevard tried to persuade him to join his order, but Caesarius only agreed to this when his traveling companion told him about a miracle allegedly performed there on the monks during the harvest. Caesarius first fulfilled his vow and went on a pilgrimage to St. Mary of Rocamadour near Cahors . This lasted five months.

At the beginning of 1199, Caesarius then entered the Heisterbach monastery and from then on stayed mainly in Heisterbach until the end of his life. Caesarius soon became a novice master in the monastery and later a prior . Here he also wrote his numerous works. Through his activity as a novice master, he was inspired to write a whole series of writings. As prior he accompanied the abbot on his visitation trips. This gave him a better idea of what was happening in the surrounding country. The places visited include the Salvatorberg near Aachen , Hadamar in Nassau , Friesland , Hesse , the Rheingau , the Eifel and the Moselle .

Caesarius' main work, the dialogue on the miracles and visions of his time, provides for the novices certain "spiritual anecdotes Collection". The a long catechism as similar work is written by the Church's view of his time, and performs particularly through the form of conversation (dialogue), the modern readers all of the ideas and opinions prevailing at that time in an otherwise rarely achieved clarity.

Year of death

The year of his death is unknown. The author has left a catalog in which he has compiled his 36 own works in chronological order. The 32nd and 34th come from the year 1237. No. 36, the last one, is an extensive Bible commentary from a total of nine books. From this it can be concluded that Caesarius put up the catalog in which he listed everything he "wrote with God's help" around 1240. Then he must have completed at least two more writings.

This is not clearly clarified in the catalog of the Archbishops of Cologne. Caesarius oversaw the section from 1167 to 1238 and must have written it in 1238 or shortly afterwards. Konrad von Hochstaden , the 50th Archbishop of Cologne and successor to Heinrich von Molenark from 1238, is only mentioned by name. It could also be that Caesarius prepared this catalog before his list of writings and did not list it there because it seemed too insignificant to him. Caesarius did not include his first sermons there either.

The eight sermons on the feasts of Mary ( De sollemnitatibus beate Mariae virginis octo sermones ), however, should have been mentioned by Caesarius in the list. Likewise, the Omelias de sanctis , the "Dominus ac salvator noster Jesus" begin and have not yet been proven. The other works that are attributed to Caesarius do not, however, fit into the context of the aforementioned list.

The Dialogus inter capitulum, monachum et novicium is probably identical to the Dialogus miraculorum . The Questiones quodlibetice Cesarii do not come from Caesarius von Heisterbach. In eum locum: In omnibus requiem quesivi is identical to the eight sermons of Mary. If one considers the time that Caesarius' works will have needed after 1237, one can conclude that Caesarius must have lived until the forties of the thirteenth century.

Fonts

Sermons

With his contemplative way of writing, which focuses on the solitude of the monastery, Caesarius sets himself in conscious contrast to the mendicant monks who roamed the country during his lifetime, came from the people and preached for the people.

The first writings of Caesarius were sermons , which he wrote down for his own practice. He later did not allow his first attempts at writing to be included in his own catalog. But it was not long before his confreres approached him, gave him suggestions and encouraged him in his plans. This is how his ninth work came into being because his fellow brothers Gottschalk and Gerhard asked him for a simple and clearly understandable explanation of the Mary sequence “Ave preclara maris stella”. Most of the other fonts were also created on request. Caesarius complains in his list of writings that his writings have been taken from his hand in an incomplete and uncorrected manner. They would be written off behind his back, and not even with the necessary care. This would lead to errors distorting the meaning, which one would then blame on him as an author. The number of surviving copies shows that Caesarius' writings were known and loved. From Dialogus miraculorum sixty known copies exist solely from the period prior to publication of the critical edition.

32 of the 36 works in the catalog are purely theological in nature. These are predominantly sermons, with the sermons clearly outweighing the homilies . There are also two pamphlets against the heretics and prayers at the canonical times of the day.

In the sermons Caesarius deals with passages from the Bible, examining whole or parts of psalms six times. He also sheds light on the relationship between the heavenly bodies and the fate of people.

The homilies, on the other hand, deal with the Gospel texts on Sundays and feast days throughout the church year. The two-volume homily dominicales is devoted to the Sunday pericopes , while the 33 homily festive is devoted to the pericopes of the main festivals with special attention to the Cistercian needs. Caesarius combined both works into a compilation, which he provided with an epistle to the reader and a dedication letter to his abbot. The homilies are to be seen as theological treatises and meditations rather than sermons and speeches. They are not aimed at lay people, but at members of the Cistercian order, monks and novices. The interpretations often deal with monastic and religious life. Caesarius considers his plays to be mystical and scholastically learned; some pieces reach a size that makes them useless for practical pastoral care. When his monastery brothers Caesarius pointed this out, he tried to keep the second part of the Homile dominicales shorter and to maintain a simpler style (“stilo breviori atque planiori”). At the same time, however, he enlarged the scope of the festive homily , although he modeled it on the already completed one and did not include any sermon tales.

The homilies not only deal with the pericope, but also contain teachings on pulpit eloquence. Caesarius speaks about the genesis of the sermon, its character and that of the preacher. His writings are of great importance for medieval homiletics . As the foreword to the first volume of the homilies reveals, Caesarius added examples “so that I can also confirm by Exempla what I could prove from the words of the Holy Scriptures” (“ut, quod probare poteram ex divine scripture sentenciis, hoc eciam firmarem exemplis "). However, the examples were criticized by contemporaries, so that he refrained from doing the homily festive . However, Caesarius later added them to his sermons.

Caesarius proves to be a connoisseur of the theological literature of his time. His sermons, with their moralizing and dogmatic discussions, are enriched with material from church life and teachings at that time. The speculation of Caesarius is typical of the theology of the time and especially that of the Cistercian order, even if it does not reach the depth and the peculiar character of Bernard of Clairvaux . Caesarius' work marks the transition between the two great periods. In most of the sermons, the author still uses the old, inorganic form that was prevalent into the twelfth century. Several times, however, he already used the new, scholastic form, which is characterized by unity and logical dispositions. For example, a sermon is divided into two fifteen sections, with Caesarius using scholastic artifacts such as number mysticism and letter symbolism .

Exempla

Caesarius' activity as a novice master led him to narrative literature, which largely established his reputation as a writer. He not only included the homilies Exempla (exemplary episodes), but also used them in the teaching of the novices for clarification and instruction. His students urged him to collect the Exempla in his own works. Caesarius took up this idea and first wrote the Dialogus miraculorum (approx. 1219–1223) with the consent of the Heisterbacher and the Marienstatter Abbot . Because of their size, Caesarius needed two codices and divided them into twelve distinctions. The number of chapters in the twelve books varies between 35 and 103. The stories are arranged according to the topics covered. The first book deals with outward conversion to monastic life, the second with repentance, the third with confession, the fourth and fifth with temptation and the tempter, etc.

Caesarius dresses his remarks in an instructive conversation. He wants to bring the most important thoughts of religious life closer to the novice. The dialogue and the speaking people are, however, kept colorless and lifeless, which emphasizes the instructive character of the work. Caesarius also creates an external connection with the homilies. The stories usually close with a moral or dogmatic interpretation that works out the intention of the Exempla to act as a warning or an incentive.

The Libri miraculorum , the second collection of specimens, is only available in fragmentary form. It was created between 1225 and 1226, shortly after the completion of the Dialogue , at the abbot's request. During this time, on November 7th, 1225, Archbishop Engelbert I of Cologne was murdered. Then Caesarius wrote the Vita s. Engelberti . A total of eight books were planned, of which only the first and second have survived. In the later, expanded version of three books, the Vita was added as a fourth and fifth book. Five surviving copies and three fragments indicate that the specimen collection has been handed down in full. The absence of the third book and books 6–8 seems to be due to the fact that Caesarius never finished them. Presumably he lost interest in the specimen collection through writing the Engelbertvita, so that he no longer dealt with it after its completion. However, some statements show that he temporarily wished the work to be completed.

Unlike the Dialogus , the Libri are not written in dialogue form. A material breakdown takes place only in a few places. Caesarius himself explains that a fixed order is not intended by him. Rather, he recorded what he heard. Dogmatic and moral explanations are found less often than in dialogue and are then usually kept more concise. For the content of the Exempla, Caesarius oriented himself to life in the Cistercian monasteries. He settles the stories in the “last generation”, that is, the time between 1190 and 1225. The scenes are primarily Cologne and Heisterbach, the Rhineland and the Netherlands .

The Exempla are located in the most diverse areas of life, different classes and ages, genders and tribes, characters and temperaments are named. There are motifs from international narrative literature. The Theophilus, Polykrates and the rapture saga are touched, but also the old Germanic mythology, which describes how the people dance around an idol, a ram, mutton or maypole, the wild hunter roars along or a dragon devours the moon. Mostly the depiction of the evil and the uncanny, of vice and hell prevails, the pleasant and cheerful is seldom heard. This should underline the instructive character of the Exempla.

The main source for the Exempla is the oral tradition. Caesarius recorded everything that was told to him by other clergy or worldly people in the form of strange incidents. In some cases he processes his own experiences, others he took from literary works, which he sometimes cites by name. He tries to name not only the source from which his story comes, but also the names of the people involved, the place of action and the time at which the event described took place. His assurance in the prologue to the Dialogue that he had not invented a chapter should therefore be sincere; Caesarius tries to report truthfully. However, in the Middle Ages people had a different understanding of 'truth' than they do today.

So Caesarius also presents the unbelievable, fairy tales and legends as real occurrences, while conversely he regards everyday things as miracles. Sometimes he also transformed events into a miracle himself. The attempt to see a miracle in everything should develop a moral effect, but also prove dogmatic propositions. With this Caesarius was a characteristic and important representative for the miracle experience and the faith of his order as well as the broad mass of the people.

Caesarius was probably the first to systematically add Exempla to the sermon. It was not until six months later that Odo von Cheriton came with the Exempla in his Sermones dominicales , and ten years later, namely in 1229, Jakob von Vitry with the Exmpla in his Sermones vulgares . With these preachers only posterity detached the exemplary stories from the sermons and collected them in an independent form; Caesarius, on the other hand, treats the Exempla more and more as an independent literary story and unites it himself in large compilations. In this way, Caesarius shaped the history of literature in a special way.

Historical writings

From the Exempla grew a third and final group of literature that Caesarius wrote, namely the historical writings. Already in the dialogue there are six smaller vitae, which string together anecdotes, visions and miracles. They describe the characteristic traits of the people concerned. These include the Vita domini Everhardi plebani sancti Jacobi or the (longer) Vita domini Ensfridi decani s. Andreae in Colonia .

This is followed by the Vita s. Engelberti immediately, after all, it was to form the fourth and fifth books of the second collection of copies. Then the Vita s was created. Elyzabeth lantgravie and finally the catalog of the Archbishops of Cologne. The last text, which was written in 1238 or soon after, is less important and is called Catalogi archiepiscoporum Colonensium continuatio II . It only covers a good seventy years and is largely borrowed from other sources.

More important is the life of St. Elisabeth of Thuringia, written between 1236 and 1237 . However, Caesarius puts more emphasis on the literary than on the historical tradition. As a source he used a booklet that contained the protocol for the canonization process of 1235 and briefly and simply reported on the spiritual life of the saints on the basis of the interrogation of their four servants. It had been sent to Caesarius by Prior Ulrich and the brothers of the German House in Marburg: Landgrave Konrad of Thuringia had a Teutonic Chapter built in the Marburg Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The clergy asked Caesarius to make a complete life story and saint's life out of the material. Even Conrad of Marburg , Elizabeth's now deceased father confessor, Caesarius had proposed for this task. He was happy to take on the task.

Unlike the Vita s. Engelberti already had the canonization, dated May 27, 1235. He could therefore rely on a written source. However, he only left this unchanged to a large extent in a few places. As Caesarius reveals in the preface, "he shortened some chapters in terms of their wording, not in terms of meaning", expanded the text and adorned it with quotations from the Bible and theological interpretation of events. In addition, Caesarius incorporated a great deal of information from oral sources and his own knowledge. Particularly important are those about the Marburg Teutonic Order, which would not have been handed down without Caesarius' vita. Here, too, the author's aim is to tell the truth and present the events in chronological order. The Vita occupies an important position in the history of the Elisabeth legend, especially since it was written by a contemporary of Elisabeth and a recognized author.

In the handwriting of the Vita, Caesarius added the sermon on the translation of Elizabeth . He wrote this based on his Vita, but probably in a close chronological context and presumably held it on May 2, 1237 for the Heisterbacher monastery community. Finally, Ceasarius sent both works together to the Marburg.

Works

- Opera selecta. Heisterbach, Cistercian Abbey (?), 13th century, 2nd quarter a. 14th century, 1st half ( digitized ).

- Dialogus miraculorum. Ulrich Zell, Cologne around 1473 ( digitized version ).

- Dialogus miraculorum. North. Rhineland, Altenberg, Cistercian Abbey, 14th century, 2nd third ( digitized version ).

- Fasciculus Dialogus miraculorum, moralitatis venerabilis Caesarii Heisterbacensis. Homilias de infantia servatoris Jesu Christi complectens / per ... Joannem Andream Coppenstein ... nunc primum ex ... MS Cod. Ad typos elaborata, Additis ad marginem lemmatis & citationibus adnotatis. Henning, Coloniae Agr. 1615. Digitized edition of the University and State Library Düsseldorf .

- The miracle stories of Caesarius von Heisterbach. Hanstein, Bonn 1933. Digitized edition , volumes 1 and 3 .

literature

- Alois Wachtel : Caesarius von Heisterbach. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 3, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1957, ISBN 3-428-00184-2 , p. 88 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Hermann Cardauns : Caesarius von Heisterbach . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 3, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1876, pp. 681-683.

- Caesarius von Heisterbach: Dialogus Miraculorum - Dialogue about the miracles . Edited by Nikolaus Nösges and Horst Schneider. 5 volumes in Latin and German. Brepols, Turnhout 2009, ISBN 978-2-503-52940-0

- Karl Langosch : Caesarius von Heisterbach. Life, suffering and miracles of the holy Archbishop Engelbert of Cologne. Introduction. Weimar 1955.

- Alexander Kaufmann : Wonderful and memorable stories from the works of Caesarius von Heisterbach , selected, translated and explained by Alexander Kaufmann, 2 parts (Annalen des Historisches Verein für den Niederrhein 47, 53), Cologne 1888, 1891

- Johann Hartlieb's translation of the Dialogus miraculorum by Caesarius von Heisterbach / from d. single London Hs. ed. by Karl Drescher. - Berlin: Weidmann, 1929. Digitized edition of the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Ludger Tewes : The Dialogus Miraculorum of Caesarius von Heisterbach. Observations on the structure and character of the work , in: Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 79th Vol. 1, 1997, pp. 13–30.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz : CAESARIUS von Heisterbach. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 1, Bautz, Hamm 1975. 2nd, unchanged edition Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-013-1 , Sp. 843-844.

- Frederek Musall: Caesarius von Heisterbach , in: Handbuch des Antisemitismus , Volume 2/1, 2009, p. 119

Web links

- Literature by and about Caesarius von Heisterbach in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Caesarius von Heisterbach in the German Digital Library

- Caesarius prior Heisterbacensis monasterii in the repertory "Historical Sources of the German Middle Ages"

- Literature on Caesarius von Heisterbach in the Opac of the Regesta Imperii

- Repertory "Historical Sources of the German Middle Ages" in the Bavarian Academy of Sciences, accessed November 15, 2012

- Caesarius von Heisterbach in the Biographia Cisterciensis

- Egid Beitz: Caesarius von Heisterbach and the fine arts, Augsburg 1926 ( part 1 , part 2 )

- Digitized version of a lost tradition of the Elizabeth legend ( memento from March 30, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Caesarius reports in Dialogus miraculorum IV. Cap. 79 that he was "abhuc puer" ("still a boy") when he heard Cardinal Bishop Heinrich von Albano preach the crusade against Saladin in St. Peter's Church in Cologne . This was in the year 1188. From this Caesarius's date of birth around the year 1180 can be deduced.

- ↑ Caesarius von Heisterbach, Dialogus miraculorum , VI, 5.

- ↑ Caesarius von Heisterbach, Dialogus miraculorum , X Cap. 44.

- ↑ Dialogus miraculorum II cap. 10.

- ↑ Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz: Caesarius of Heisterbach. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 1, Bautz, Hamm 1975. 2nd, unchanged edition Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-013-1 , Sp. 843-844.

- ^ Letter to Prior Petrus von Marienstatt , which Caesarius wrote about a collection of Tractatus minocres . Epistola Cesarii ad dominum Petrum priorem de Loco sancte Marie in diversa eius opulescula , edited by A. Hilka, Die Wundergeschichten des Caesarius von Heisterbach I (1933), p. 2 ff.

- ↑ In the list of writings Caesarius says: "Primo omnium in adolescencia mea paucis admodum semonibus prelibatis ... scripsi ..."

- ↑ A. Hilka, Die Wundergeschichten des Caesarius von Heisterbach I (1933), p. 31 ff.

- ↑ A. Hilka, Die Wundergeschichten des Caesarius von Heisterbach I (1933), p. 60.

- ↑ A. Hilka, Die Wundergeschichten des Caesarius von Heisterbach I (1933), p. 33f.

- ↑ PE Hübinger at A. Hilka, Die Wundergeschichten des Caesarius von Heisterbach II .

- ↑ In the commentary on Psalm 118 of 1137, Caesarius notes: "In libris visionum, quos nunc manibus habeno". Libri visionum is an imprecise specification, meaning the Libri miraculorum . Caesarius still speaks of libros VIII in the list of scriptures .

- ↑ IV cap. 98

- ↑ VI Cap. 5.

- ↑ Published in the MGH. Scriptores 24 (1879), pp. 345-347.

- ↑ Vita sancte Elyzabeth lantgravie , edited by A. A. Huyskens at Hilka, the miracle stories of Caesarius of Heisterbach III , p 329 ff.

- ^ "Sermo de translatione beate Elysabeth", edited by A. Huyskens at A. Hilka, Die Wundergeschichten des Caesarius von Heisterbach III (1937), p. 387 ff.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Caesarius von Heisterbach |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Caesarius Heisterbacensis |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Monk, Cistercian, chronicler |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1180 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | uncertain: Cologne |

| DATE OF DEATH | after 1240 |

| Place of death | Heisterbach Monastery , Germany |