William I (England)

William the Conqueror ( English William the Conqueror , Norman Williame II , French Guillaume le Conquérant ; called William the Bastard before the conquest of England ; * 1027/28 in Falaise , Normandy , France ; † September 9, 1087 in the monastery of Saint-Gervais near Rouen , Normandy, France) was from 1035 when William II. Duke of Normandy and ruled from 1066 to 1087 as William I and the Kingdom of England .

The Romanized Norman was the progenitor of the short-lived Norman dynasty in England, which died out in the male line as early as 1135 with his son Henry I (called "Beauclerc"). The Domesday Book , which he issued, still serves in part as a legal source today, and above all it is an outstanding source for economic and social history.

Life

origin

Wilhelm comes from the Rollonid dynasty , which was of Scandinavian origin and ruled Normandy since 911. He was the son of the Norman Duke Robert I from his relationship with Herleva , the daughter of a Norman tanner named Fulbert and his wife Doda from Falaise. He came from a common (polygamous) marriage among Vikings " more danico " (according to Danish custom), whereby the descendants were considered legitimate. Since this “marriage” came about without a church blessing, Wilhelm was also referred to as “Wilhelm the bastard” at first.

After the birth of their daughter Adelheid, Herleva was married to Robert's friend and henchman Viscount Herluin de Conteville around 1031 . The marriage resulted in four daughters and two sons: Robert , later Count of Mortain, and Odo , later Bishop of Bayeux .

Immaturity

In 1034 Robert I made the decision to go on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem . In order to secure his kingdom in the event of his death abroad, he persuaded the feudal lords to recognize Wilhelm as a legitimate descendant. They swore to William, fealty and obedience. "William the Bastard" ('le Bâtard') began his Norman rule. During the absence of his father, Wilhelm's rule was supported by Robert I's loyal followers, who took over the guardianship. These were Robert , Archbishop of Rouen , and Count Alan III. von Bretagne , Osborn, the steward, and Turchetil, the paedagogus (educator) of the young duke. The most important of them was Archbishop Robert, who, as the younger brother of Duke Richard II - and thus uncle of Robert I - could have claimed the office, but did not. Shortly before Robert I's departure, the French King Henry I had given his consent to the succession plan; probably Wilhelm had traveled to the court to take the royal feudal oath. But in spite of all this, Wilhelm's situation remained uncertain; almost all of his protectors were violently killed.

Alan III died in 1040. unexpectedly, whereupon Gilbert took over as chief guardian and was killed a few months later. Almost at the same time, Turchetil was killed. Osborn was murdered in a fight in Wilhelm's bedroom in Vaudreuil. Herleva's brother Walter usually slept with his nephew and often had to flee with the boy. There was an uproar in Normandy. The fact that Wilhelm survived his minority at all was largely due to the policy of the French king: When Wilhelm took office, Heinrich I demanded his feudal rights to the duchy, for which he expressed his support and recognition for Robert's succession plan. The king could demand the right of guardian for the child of a deceased feudal man, whereby he also took responsibility for its safety. For the duration of the minority the king exercised direct rights over Normandy.

marriage

Around 1049 , a marriage was planned between Wilhelm and Mathilde , daughter of Baldwin V , Count of Flanders, and granddaughter of Robert II of France . This connection forbade Leo IX. at the Council of Reims in October 1049, presumably because of the close relationship. Wilhelm and Mathilde were cousins and 5th cousins, as both descended directly from Rollo the Viking . The marriage nevertheless took place in Eu in 1051 . Wilhelm immediately brought his wife to Rouen. Initially, however, the marriage led to the excommunication . The connection was finally approved by Pope Nicholas II in 1059 , after he had concluded an alliance with Wilhelm's relatives, the southern Italian Norman leaders Richard von Capua and Robert Guiskard . Out of gratitude or to vote favorably for the Pope, the couple founded a monastery east and west of the castle in Caen : the ladies' abbey ( Abbaye-aux-Dames ) and the gentlemen's abbey ( Abbaye-aux-hommes ). Construction began for both abbeys in 1066. Mathilde was buried in St.-Trinité in the Abbaye-aux-Dames .

Wilhelm's marriage to Mathilde von Flanders made his power so threatening in the eyes of the King of France that Heinrich dropped his previous ally and settled with Gottfried von Anjou , Theobald III. von Blois (Theobald I of Champagne) and rebellious Norman barons allied against him.

Duke of Normandy

The years 1047 to 1060 were of the utmost importance in the history of Normandy. The prelude was an uprising in 1047, which almost overthrew the duke. This was followed by a second crisis in which between 1052 and 1054 William had to oppose not only a hostile alliance of his own vassals, but also a union of French feudal men under the leadership of their king. During these 14 years the Duke was almost continuously in a state of war. After 1054 the situation eased. Wilhelm had freed himself from the dependence of the French king and repulsed the joint attack by Paris and Anjou ( Mortemer 1054 , Varaville 1057 ). He had proven victorious and decisive; his authority was largely due to the expansion of his power in Lower Normandy. The rise and the resulting increased competition with the Anjou family were a new factor in Norman politics.

The strength of Normandy, as it developed under William, was mainly due to the rise of a new aristocracy and their interests coinciding with those of the duke. But to a large extent his success was also to depend on the ecclesiastical renewal of the province, which he had already begun with his successor and which gained more and more importance under his rule. There was a monastic renewal that began under ducal patronage and continued independently, as well as a reorganization of the Norman Church, which began with a group of powerful bishops. During the decades leading up to the Norman conquest, the main goal was to put aristocratic and ecclesiastical developments in direct relationship. A great advantage were the rights that the ducal office was granted by tradition. In this way, Wilhelm was able to enact laws throughout the duchy and pronounce justice within certain limits. He was able to mint money, raise certain taxes, and as the “ruler of Normandy” he had - at least in theory - a military force at his disposal.

With increasing age, Wilhelm was faced with the main task of asserting the rights of his dynasty in the midst of a changing society and of including the feudal aristocracy as far as possible in the administrative power. The main institutions were the counties and vicomtés, which in the 11th century were directly related to the feudal nobility and were essential for the ducal administration.

Norman counts did not appear on the scene until the beginning of the 11th century; their establishment was an extension of the ducal power. All these men came from the ducal line, the counties were at strategic points, the only danger was the personal infidelity of a member of the ruling families to their head. On the other hand, the vicomtés, who had become the inheritance of the new feudal families, were more problematic. As deputy to the Count of Rouen, you were to perform duties which previously fell within the jurisdiction of the vice-count's office. This should largely account for the success of Wilhelm's administration. Her duties included the collection and payment of ducal funds and the enforcement of ducal jurisdiction, and her greatest responsibility lay in the military field.

After 1057, but especially between 1060 and 1066, the duchy under Wilhelm became so strong that he was soon able to venture into a foreign country. In addition, death had finally freed him from his two most dangerous opponents in France - Count Gottfried and King Heinrich. In 1066 the farm was changing. Many powerful officials (e.g. the steward , the cellar master and the chamberlain ) were already firmly established and surrounded by less important officials ( master of ceremonies , numerous bailiffs). It was a feudal court whose task it was to support its liege lord in every way. The conquest of England was prepared and made possible by the growth of Norman power and the consolidation of the duchy under the rule of Wilhelm. A close political bond between Normandy and England formed part of the heritage.

England before the Norman conquest

After Æthelred II married Emma , the daughter of Duke Richard I of Normandy , in the second marriage in 1002 , the Normans came into play and language had been romanized. The deposed Æthelred died 1016. A Danish fleet under Knut the Great , the second son of the Danish king Sven Forkbeard , who already from 1014 Witan - a meeting of the most powerful spiritual and secular dignitaries - was proclaimed King of England who came Thames up against London before. Æthelred's son, Edmund Ironside, was unable to hold the divided English army together in the face of the enemy. When he died in November of that year, England bowed to King Canute - now elected by the Witan - who ruled over a North Sea empire until 1035 . Canute the Great gave England a firm system of rule for the last time before the Norman conquest.

Claims to the English throne

Since 1042 the Anglo-Saxon King Edward the Confessor ruled over England. Before his coronation, he spent several years in the Duchy of Normandy , whose structures he regarded as a model. In order to give England a similar administration, he also set up a central administration and filled numerous important positions with Normans. In 1050, therefore, there was an uprising of the Anglo-Saxon nobles under the leadership of Godwin of Wessex , Edward's father-in-law. Eduard was able to suppress the uprising and in 1051 expelled the ringleaders from the country.

During this time, Wilhelm visited Eduard, who was a cousin of his father. Since Edward himself had no children, he is said to have made him promises on this occasion that Wilhelm would be his successor on the throne of England. In 1052 the Godwins family returned with armies, and Eduard had to reinstate them. When Godwin died in 1053 at a meal with Eduard, his son Harold Godwinson succeeded him as the most powerful English duke.

In 1064, Eduard sent Harold across the canal to Wilhelm and suffered a severe shipwreck in which five of his men died. He was captured in Beaurain by Count Guy de Ponthieu . When Wilhelm found out about this, he freed Harold from the Count's hands, took the oath of allegiance from him and went on a victorious campaign with him. In this way, Wilhelm not only secured the promise of the current ruler of the succession to the throne, but also obliged his toughest rivals for the throne to obey. Harold, of course, saw this oath as not binding, in his opinion it had been taken under duress while in captivity.

Norman times in England

Death of the last Anglo-Saxon king

Edward the Confessor died on January 5, 1066. Since he left no descendants, it was foreseeable that the succession to the throne would be clarified in acts of war, in which Wilhelm would play an essential role. The actors also included Harold Godwinson , his brother Count Tostig of Northumbria and King Harald Hardråde of Norway . Harold Godwinson was chosen by the Witenagemot as the new king and was crowned king immediately after Edward's funeral in Westminster Abbey . Wilhelm, however, insisted that Eduard had already chosen him as his successor. He therefore saw Harold's rise to power as a personal insult and a political challenge. He was aware that his claims could only be enforced by force.

Battle for the throne

In the first half of 1066 he secured the support of his vassals (see also Companion William the Conqueror ) and promoted divisions between rivals. He successfully turned to European public opinion and made important preparations for armament. Since it was dangerous to leave the duchy without a ruler and most of the armed forces, Wilhelm took special measures to secure it. His wife Mathilde and their son Robert were given special responsibility during his absence, and Robert was solemnly appointed heir to the duchy at a meeting of the feudal lords. The most important men of Normandy swore allegiance to him. In addition, established members of the new nobility were directly entrusted with the administration of Normandy. The construction of ships began in the spring of 1066, and the new ships were pulled together in the Dives estuary as early as May, where work continued and was probably completed in August at the earliest.

At the beginning of May 1066, Tostig attempted to return to England from exile by force of arms. He devastated the Isle of Wight and then occupied Sandwich , where he took sailors into his service and sailed with 60 ships on the east coast to the mouth of the Humber . When he went on a rampage in Lincolnshire , his army was destroyed by the Count Edwin of Mercia . The survivors fled, Tostig sailed north with the remaining twelve ships and sought refuge with King Malcolm of Scotland , with whom he had made an alliance. Harold Godwinson went to the Isle of Wight to arm the south coast against the Norman Duke. Harald Hardråde was known to be preparing for an invasion and was in contact with Tostig waiting in Scotland , but Harold's attention was primarily on Wilhelm.

Wilhelm's powerful vassals gathered with their tenants on military service to form the core of the army, for which volunteers flocked from other regions - including Maine , Brittany , Poitou, and Flanders ; the army will have been between 5,000 and 10,000 men strong. Most of them were mercenaries , so it was Wilhelm's urgent task to turn this mixed troop into a disciplined force.

On August 12th the fleet was ready to go and, only separated by the narrow channel , the rivals faced each other. Both Wilhelm and Harold had similar problems. In particular, there was the conversation of a large army about the preparation time without devastating the area in which it was billeted. Wilhelm forbade all forms of looting and generously supplied his troops, which Harold failed to do, and after weeks of waiting it became clear that he could no longer supply or hold his army together. Harold's army began to disintegrate on September 8, 1066, and he himself withdrew to London with his housecarls . The ships were also supposed to return to the capital, and many went down on the voyage there. The south coast was now undefended, whereupon Wilhelm sailed with his fleet to the mouth of the Somme . After suffering some damage along the way, they arrived in Saint-Valery-sur-Somme , where repairs were being carried out and the only thing left to do was to wait for a good wind to set sail.

The situation changed within the waiting period. Harald Hardråde began his attack on England. The Norwegian king arrived on the river Tyne with 300 ships, where Tostig joined him. Together they advanced to the mouth of the Humber by September 18 , landed at Riccal and moved to York .

On September 20, 1066, the first of the three great English battles took place, from which Harald Hardråde emerged victorious. York received him enthusiastically, and after making arrangements for the city, he withdrew with his troops to the ships. Harold Godwinson immediately set out north with his entire army. In Stamford am Derwent he met the Norwegian enemy at the Battle of Stamford Bridge and attacked immediately. Harold won, Hardråde and Tostig perished in the battle. Now the question was whether he could get south in time to face Wilhelm's imminent landing. Harold let his exhausted troops breathe in York for two days after the battle. At this time a favorable wind came up, and Wilhelm hastily embarked his troops. They set sail on September 27th and landed at Pevensey on the morning of September 28th , where they hardly expected any resistance. The old Roman fortress was provided with an inner rampart, and Wilhelm tried to use the conditions of the coast to his advantage. It was important to maintain the connection to his ships.

Battle of Hastings

Hastings had an excellent harbor that Wilhelm could use as a landing stage, and was at the time at the base of a small peninsula that could be defended by a cover force in case he had to re-embark his army. So Wilhelm moved troops and ships to Hastings, built a fortress within the city and waited. He devastated the surrounding land to incite his enemies to attack before his resources were exhausted.

On October 11th, Harold and his army (mostly infantry) moved south to Hastings. He had come north with most of his force, but had been in such a hurry on his way south that he had had to leave some of his infantry and archers behind. Apparently he wanted to repeat the tactics of the battle of Stamford Bridge, surprise William and cut him off from his ships, but this was no longer possible due to the exhaustion of his troops. He took up position near Battle . When Wilhelm found out about this, he saw his chance, marched on Battle and attacked immediately. Harold's troops were on a hill, a strong position that Wilhelm had to advance against, and his army was somewhat weaker. But the advantage was the larger proportion of professional warriors and a larger contingent of archers. Wilhelm won the battle, Harold was killed. After his victory he returned to Hastings and let his troops rest. The departure took place five days later.

At the end of October the troops came to a standstill, a stay that lasted five weeks, during which the supply was extremely difficult and the dysentery broke out. The break also brought benefits, as news of the battle spread and the areas of Kent began to surrender one by one. But it turned out even better for Wilhelm, for Winchester , the old capital of the West Saxon kings, dowry of Edith, the confessor's widow, offered her submission. So at the end of November Wilhelm could see himself as master of south-east England. Sussex , Kent and part of Hampshire were under his rule. The attitude of the north and London, however, was not yet clear. London was the junction that dominated the country's routes to the Thames and the sea, but it was too big for the city to be taken by storm. Wilhelm therefore decided to isolate the city. After setting fire to Southwark , he headed west, devastating northern Hampshire and invading Berkshire . From there it went north, and finally, completing the loop , he reached Berkhampstead .

Now the high lords of the country came to him and submitted, with which only the Norman feudal lords had to consent to his accession, which they did, and he was able to advance to London with the most important men of Normandy and England. A few days before Christmas he moved into his new capital and immediately made arrangements for his coronation.

William I the Conqueror (1066-1087)

On Christmas Day 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, was crowned King of the English in Westminster Abbey according to old English custom. Wilhelm took over the rights and duties of an old English king and, although he had only taken possession of parts of the country, he was able to proclaim peace in the whole of England . The new king (now called "the Conqueror") had three fortresses built on the Thames ( Tower of London , Baynard's Castle and Montfitchet Castle ) to protect the city from further attacks by the Vikings and to prevent possible uprisings by the locals.

In order to be able to monitor the capital, he moved with his army to Barking , which completed the encirclement of London. In the Barking monastery he called a meeting of English feudal lords, from whom he demanded recognition and submission and in return promised gracious rule. At the beginning of March his power was so secured that he could return to Normandy. He entrusted England to some loyal Norman feudal lords. William Fitz Osbern was installed in Norwich (possibly Winchester), Bishop Odo of Bayeux was entrusted with the fortress of Dover and the Kent area. Wilhelm carried a large group of the most important men in England as hostages on his journey home.

He was received with great enthusiasm in Normandy. In France, Maine and Brittany, on the other hand, there was unrest because the French monarchy was not well disposed to its most powerful vassal. Up to now only part of England was under Norman rule, and the Welsh princes and the Scottish king sat attentively beyond the vague English borders. In addition there was the resistance of Scandinavia, which England did not want to give up easily.

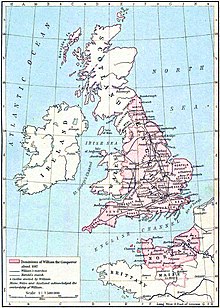

So the decision of 1066 had to be confirmed. It was important to maintain Norman power and supremacy in the duchy and to complete the conquest of England. In addition, the Anglo-Norman Empire had to withstand the Scandinavian threat. Wilhelm started the task. From the end of 1067 to 1072 he was mainly occupied with suppressing English uprisings and securing his power. In 1072 he decreed to move the bishopric of England to fortified cities. Between 1073 and 1085 he spent most of his time in Normandy but had to fend off Scandinavian attacks (1069, 1070, 1075). In 1085 the conqueror returned to England because of another very threatening attack. William celebrated Easter 1086 in Winchester and held a large court at Whitsuntide in Westminster, where his wife Mathilde was solemnly crowned queen in 1068.

In 1069 William had brought almost all of England south of the Humber under his rule. In the summer of the year, however, the Scandinavian resistance increased; a strong Scandinavian army was in England and was reinforced by a sizeable army of powerful Saxon feudal lords. The news that spread quickly brought further uprisings, but the heart of the danger lay in the north. Wilhelm acted quickly. He went immediately to Axholme , whereupon the Danes moved back over the Humber to Yorkshire. Wilhelm left the Counts of Mortain and Eu at Lindsey and went west himself. He suppressed the rebellion that had broken out under Edric the Wild and the Welsh princes without difficulty and then moved on to Lincolnshire, where he left Bishop Geoffrey of Coutances to put down the uprising in Dorset.

When he arrived in Nottingham , he received a message that the Danes wanted to reoccupy York, whereupon he immediately turned north. He moved towards the capital, whereupon the Danes withdrew again. On the way he ruthlessly devastated the country. He arrived in York just before Christmas. The Norman troops divided into small groups and systematically devastated Yorkshire. After that, it quickly moved further west, where it was more difficult to suppress the uprising. He reached Chester before his enemies were ready, occupied the town and built a castle here and in Stafford .

The resistance was broken and the Danish fleet left the Humber in the face of the defeat of their English allies. Wilhelm moved south again and reached Winchester before Easter. The first rebellion had survived the Norman regime in England, the main English cities had surrendered, the north had been defeated and the Fenland rebellion had been suppressed. At the beginning of 1073, Wilhelm was at the head of an army that was translating from England to Normandy. His opposition here was now so organized and strong that he had to spend most of his time in Normandy. In 1074 his opponents began to act together on both sides of the canal. Edgar Ætheling , grandson of the Anglo-Saxon King Edmund II , returned to Scotland from Flanders, and the French king immediately realized that he could be used as the center of a counter-Norman alliance. Wilhelm felt the threat was so great that he negotiated with Edgar Ætheling and agreed to take him back to his court.

Uprising in Normandy

King Philip I of France had to establish another center of resistance. That finally happened in Brittany. A policy developed there between 1075 and 1077 that allied the English, French and Scandinavian enemies of Wilhelm for some time. Robert , Wilhelm's son, had until then shown himself to be loyal to his father. In 1078 he let himself be persuaded by the flatteries of his companions and asked his father to give him independent power over Normandy and Maine.

However, since a split in the Anglo-Norman Empire would have been dangerous at this point in time, Wilhelm shied away from a rash act. In the end he was forced to stifle a quarrel that had broken out between Robert's followers and those of his two other sons, Wilhelm and Heinrich . It came to an open break, Robert immediately left his father's court and tried with a large retinue to bring the city of Rouen into his possession, but it withstood the attack. Wilhelm countered immediately, ordered the rebels to be captured and threatened them with expropriation. Robert and many of his followers fled Normandy. This was Philip's long-awaited opportunity.

Contingents of troops were sent to Robert from France, Brittany, Maine and Anjou. Wilhelm attacked the rebels assembled in Rémalard immediately, whereupon they withdrew and entrenched in the Gerberoy castle , which Philip had given them. Robert received new encouragement from Normandy, and many knights from France also joined him. The siege of the fortress lasted three weeks before the besieged attempted an escape, which had unexpected success.

Robert remained victorious, Wilhelm returned to Rouen and felt compelled to negotiate. The reconciliation between father and son took place in March or April 1080, but Wilhelm's influence on his son was considerably weakened. The news of this defeat prompted King Malcolm of Scotland to attack. From August 15 to September 8, 1079, he devastated the whole area from tweed to teas , which brought him rich booty. The fact that he went unpunished for some time strengthened the opposition in Northumbria .

In the spring of 1080 an uprising broke out which threatened all Normans in the north and culminated in the murder of Bishop Walcher and his entourage. Wilhelm was still in Normandy, but Odo von Bayeux was sent north on the punitive expedition. In the same year Robert moved to Scotland with an army and forced Malcolm into a contract. Then he turned south and built a fortress at Newcastle ; the land north of the Tyne was still disputed territory.

Wales gave William little trouble during his reign; Scotland was different. During his reign, the north was a constant threat and there was always some relationship with the attacks on his possessions in France. In 1081, Count Fulko IV of Anjou launched an attack on Normandy from Maine. He was supported by Count Hoël II of Brittany. So Wilhelm had to cross the canal again and marched with a large army against Maine. The church stepped in, and so a contract was signed between the king and the count, but Maine kept boiling.

At the same time, however, Wilhelm's position was also threatened from within his own family. In 1082 there was a dispute between Wilhelm and his half-brother Odo von Bayeux. Wilhelm had Odo locked up. The reasons are unclear, but presumably Odo aspired to the papal crown and tried to persuade important vassals of the king to undertake an enterprise in Italy . He was probably held prisoner until Wilhelm's death in 1087, but not expropriated, because in the Domesday Book he continues to appear as the largest landowner next to the king. Odo's apostasy was a great danger.

In 1083 Robert rebelled for the second time and left the duchy. He disappeared from history for four years; what he did is questionable, but he remained an important intermediary for the French king who gave him full support. The two most important members of the family had publicly opposed Wilhelm. Towards the end of the year he was hit particularly hard, because his wife Mathilde died on November 2, 1083.

Last uprisings

The beginning of the crisis was dated 1085 in the Anglo-Saxon chronicle. Canute IV. The Saint renewed the Scandinavian claims to England. In France, Philip continued to support Robert, who was still in opposition to his father.

Odo, although still in captivity, was able to incite the English and Norman subjects of Wilhelm to betrayal. Malcolm stood as an enemy on the Scottish border and Fulk de Anjou was ready to take advantage of the situation. Wilhelm had to defy this threat, to which the personal grief came. Wilhelm aged quickly and had only recently lost his wife, whom he is said to have loved very much. He could only rely on a few family members, his health had deteriorated, he was becoming more and more obese.

The energy with which he faced his enemies shows his remarkable determination and willpower. When he heard of the impending invasion of Knut, he acted quickly and decisively: he devastated coastal areas of England. This act deprived the Northmen, who took care of themselves by looting from the surrounding area, the opportunity to gather their strength undisturbed on the coast. Instead, they had to be prepared to let their entire army march for several days without supplies, until there was a prospect of unspoiled villages and thus a supply of food again. He left the defense of Normandy to others; he himself crossed the canal with an army composed of infantry and cavalry - the largest he had ever carried with him. He distributed his army over the estates of his liegemen and ordered them to feed these departments according to the extent of their lands. This combination of "scorched earth" in the coastal area and troops standing by inland initially thwarted the invasion. The Northmen left without having achieved anything.

At Christmas 1085 he was in Gloucester holding court and conferring with his counselors, which was followed by the creation of the Domesday Book . Afterwards Wilhelm traveled through southern England, at Easter 1086 he was in Winchester and at Pentecost in Westminster, where he knighted his son Heinrich. Knut had meanwhile gathered a large army and a mighty fleet in the Limfjord , but encountered resistance and dissatisfaction from his subjects during the preparation period. In the riots that followed, he was captured and murdered in Odense in July 1086 . This ended the campaign before it really started and the immediate Scandinavian threat averted. The situation remained serious, however, because Robert rebelled and Odo encouraged the treasonous movements directed against Wilhelm.

Since in 1086 attention had necessarily turned to England, a favorable opportunity arose for Philip to resume his military activities in France. So Wilhelm embarked for France again in 1086 and focused primarily on defense. When in the late summer of 1087 the garrison of the French king of Mantes invaded the Évrecin and began to sack Normandy, Wilhelm decided to retaliate. Before August 15, he undertook a campaign to regain the Vexin , but especially the cities of Mantes, Chaumont and Pontoise for Normandy. The following campaign was Wilhelm's last and one of the bloodiest. He crossed the Epte and devastated the country with a large force as far as Mantes. When the occupiers there attempted a sortie, Wilhelm surprised them, whereupon they withdrew to the city. Terrible destruction followed, Mantes was so completely burned that today it is hardly possible to discover traces of buildings from the 11th century. The capture of Mantes was Wilhelm's last military act.

Death and succession

While riding through the city, he suddenly suffered a very painful illness or injury; there are contradicting traditions about this. He was forced to return to Rouen in severe pain. There pain and illness increased from day to day, Wilhelm was tied to the bed. Family and friends gathered around his bed, the two most important members of his family still missing, for Robert was still rebellious and in the company of Philip, and Odo was still in prison. Present were the other sons of the king, his half-brother Count Robert von Mortain , Archbishop Wilhelm Bonne-Ame, the Lord Chancellor Gérard von Rouen, the highest officials of the court and many others.

Wilhelm died slowly and painfully, but was able to give final instructions because he was in his right mind until the end. When it came to the end, he was not particularly afraid of death, he confessed and received absolution, after which he arranged for a generous distribution of alms and had the clergy precisely record to whom his gifts were to be sent. He exhorted everyone present to ensure the upkeep of law and the upholding of the faith and finally ordered all prisoners to be released, with the exception of the Bishop of Bayeux. Here those present defied him, especially Robert von Mortain asked for his brother's release. They discussed for a long time, and finally Wilhelm gave in exhausted. The transfer of the empire was of the highest importance, and Wilhelm declared himself with justified bitterness against Robert Curthose ; Faithlessness, but also the inability to rule without admonitions and supervision, prompted him to do so. The feudal lords tried to cement and eventually he agreed to appoint him as Duke of Normandy.

With regard to England, however, things looked different. He bequeathed the throne there to his second son Wilhelm II Rufus . Since he was aware of the unrest that followed his death, he sent a sealed letter to Lanfranc in England with his provisions and immediately had Wilhelm leave with them. Wilhelm had already reached Wissant when he learned of his father's death. Wilhelm left a considerable fortune (5,000 pounds silver) to his son Heinrich the Scholar , and he, too, was immediately dispatched to secure the sum. The separation of Normandy from England had long been Philip's main goal, which Wilhelm had constantly opposed. Now this goal seemed to have been achieved, and the dying king must have felt it was his last defeat. After William received his instructions, he received the last unction and the Lord's Supper from the Archbishop of Rouen. He died in the early morning hours of September 9, 1087.

The king's body was transferred from the Saint-Gervais monastery near Rouen to the Norman capital Caen . There he was received by the abbot of Saint-Étienne , Gislebert de Coutances, and led through the town in a procession to the abbey church. Everyone of rank and name attended the service - except for the royal sons.

The first Norman King of England is - or better: lay - buried in the Abbey Church of Saint-Étienne in Caen . However, the grave was looted, in 1522 in the Huguenot Wars and again in the French Revolution . Therefore, of the remains of Wilhelm today, it only contains a thigh bone - the authenticity of which is doubted. Today's tombstone was created in the 19th century.

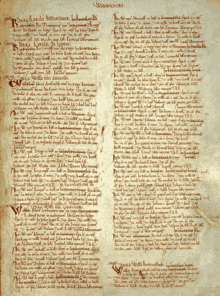

Domesday Book (Book of Winchester)

In 1085 William I announced his decision to create a "descriptio totius Angliae", a description of the country for the whole of England, on his Christmas Court Day ( curia regis ) in Gloucester on the occasion of his 20th anniversary on the throne. In view of the impending Danish invasion, it became necessary to clear up the many unclear things about the distribution of property and burdens. They had turned out to be a general land tax , especially when collecting Danegeldes . The then created land register was called the book of Winchester , later also Domesday Book ("Book of Judgment Day ", based on the declared finality of the landed property relations). To this end, the rulership south of the Tyne was divided into districts, which two groups of royal officials as commissioners traveled to at different times in order to document in detail the English property in its rulership.

All lands, owners and residents, livestock and land holdings were recorded. A comprehensive catalog of questions asked about the name of the respective place, about its owner before the Norman conquest in 1066 and that at the time of the survey, about the size of the place in Hides (medieval area measure) and the number of plow teams that each included eight oxen were added and were available on the local farms and the manor.

In addition, the number of villages in the area concerned, the number of kötter, farmhands, free men and court dependent free, the forests, meadows, pastures, mills and fish ponds, the respective changes in ownership, and the total value at the time of the survey were determined. Finally, the size of the property owned by free and court dependent farmers before 1066, when the land was awarded at the time of the survey. In addition, it should be asked whether more can be taken in the respective areas than was the case at the time of the survey.

The survey was completed in 1086 after nine months. The brevity of time may be one of the reasons data are not available for both Northumberland and Durham, as well as several cities including London and Winchester. The data has been combined into two volumes, the first of which deals with 31 counties and is referred to as the "Great Domesday". The second volume, called Little Domesday, contains dates from Essex, Norfolk and Suffolk.

The Domesday Book served to secure property titles and an effective collection of taxes. The property of the surveyed areas was estimated at £ 72,000. As taxable served the number of plow lands, depending on the region in Carucatae or Hiden measured. The total number of hides listed is given as 32,000, which means that one hid was valued at a little over two pounds. The annual taxes were two shillings per hîde, or five percent of the total land value.

The Domesday Book lists more than 13,000 rural settlements with a population of 269,000, although only male heads of household are included. Of these, 109,000 people belonged to the group of non-aristocratic rural residents (villani), 89,000 to the group of small business owners (bordarii), 28,000 to the group of the unfree (servi) and 37,000 people to the group of the free. Assuming a household size of five people, the size of the rural population at that time was about 1.34 million. With regard to the cities, the information from the survey of 1086 is less comprehensive. However, an estimated 150,000 people lived in the 112 boroughs , so that the total population of England at the end of the 11th century, or the areas not covered by the Domesday Book , is likely to have been 2 million.

It was not up to the baronial courts to draw up the land register , but rather to the commissioners who the municipalities called upon for their inquisitions. The procedure itself had been taken over by Normandy. The commissioners' questions were answered by a jury made up of equal numbers of Normans and Anglo-Saxons. The older legal relationships were apparently taken into account, but each municipality or its parts were classified in a fiefdom. In doing so, the commissioners used the feudal terminology of uniform Anglo-Saxon relationships that they are familiar with, so that the extent of the reference to the Anglo-Saxon legal situation was obscured.

According to the Domesday Book of 1086, almost half of the land was in the hands of the lay barons. Of the more than 170 secular magnates, only two were of Anglo-Saxon origin, and the local landowners only owned eight percent of the land. The largest landowner was the king and next to him the church, whose individual goods were mostly treated like knights' fiefs with public service.

In addition, the entire land as "Feod" was subordinate to the supreme suzerainty of the king and no allod was recognized as an independent property. Since every land was regarded as a fiefdom and every owner as a crown vassal or sub-vassal, the previous personal ties were now replaced by feudal ties and no country without a lord and no lord without an overlord except the king. Over time, the idea of free land with no service attached receded. With the Domesday Book , the whole country was under the feudal hierarchy of the Norman system, so that the fief pyramid extended seamlessly from the king, as "Lord Paramount" of England, through crown and sub-vassals to the smallest landowner and no region was without a seigneur. From him and the manor district, and not from the village parish, the officials now collected the amount of tax imposed on the county.

All in all, the most closed feudal monarchy in Western Europe was created. In 1086 in Salisbury , William had an alliance between France, Norway and Denmark swear against him a general oath of allegiance, which all persons who owned land had to take. Of course, the king himself had to bow to the norms of the feudal constitution. The heredity of the fiefs was assured and an increase in the inheritance fees was not simply permitted. Confiscated fiefs could not simply be added to the crown domains. In particular, the fiefdoms associated with an office were considered to be the legal status of the magnate families and could not be merged with the crown property. Heredity gave rise to noble dynasties, of which around 100 families formed the high nobility at the time of Henry I , who of course could not claim any specific rights that could be clearly defined.

In the years 1274 and 1275, the English King Edward I sent two officials to each county of the kingdom to clarify the ownership situation. This is how the Hundred Rolls , a new edition of the Domesday Book , came about . The investigation also uncovered numerous cases of abuse of office by royal officials, against whom Edward passed new criminal laws.

Wilhelm and the Church

Wilhelm brought numerous foreign clergy to England who displaced the local clergy from the dioceses, abbeys and cathedral chapters and leaned towards the efforts of the church reform party. He made the Lombard jurist and prior of Le Bec Abbey in Normandy, Lanfranc (1010-1089), Archbishop of Canterbury (1070-1089) and his first advisor. After heavy fighting, celibacy was enforced for the parish clergy. With a few exceptions, the bishops were Normans; they had to reside in the cities and were under the supervision of the Archbishops of Canterbury and York .

The spiritual jurisdiction was separated from the secular in 1076; however, it encompassed broad areas of general life, such as marriage and inheritance law and the criminal justice system for breaking oaths, defamation and insulting priests. The bishop resigned from the county court, whose direction he previously held together with the sheriff or the Ealdorman . This separation freed English law to develop independently, but also opened the church to the advancing canon law. The great churches of the Saxon period were gradually replaced by impressive monumental church buildings such as Canterbury , Rochester , Exeter and Durham ; the formation of the time was essentially borne by the new clergy, whose formation was shaped by the continent.

Wilhelm asserted himself as the undisputed overlord of the English Church and reserved the appointment of all bishops and abbots, whom he endowed with extensive fiefs. Numerous church properties remained knightly fiefs with public service. In his own interest, Wilhelm favored the Reform Party and through the Church was not only king, but real ruler. He maintained his independence from the political claims of the papacy from the Constantinian donation , according to which all islands should be subject to the papal suzerainty. He paid the church dues as before, but as alms and not as tribute. Papal measures or bulls required his approval. It was only under his successors that an open conflict arose.

Linguistic diversity

Norman French became the language of the English upper class (nobility) and administration. The court language of the higher authorities was Latin and French; the clergy spoke Latin, but the vast majority of the population continued to speak Anglo-Saxon.

progeny

There is some doubt about the number of his daughters; currently the list of his children looks like this:

- Robert II Curthose (* 1054; † 1134), Duke of Normandy

- engaged (the wedding did not take place) since 1059 Margaret of Maine († 1063)

- ⚭ 1100 Sibylle di Conversano († 1103)

- Adelizia (or Alice) (* 1055; † 1065)

- Cecilia (* 1056; † 1125), Abbess of Caen

- Richard (* 1057, † 1081, unexplained hunting accident with a stag), Duke of Bernay

- Wilhelm Rufus (* 1056; † 1100, murdered by William Tyrrel ), King of England

- Adela (* 1062; † 1138) ⚭ 1080 Count Stephan II of Blois and Chartres (* 1045; † 1102)

- Agatha (* 1064; † 1080), died as the bride of King Alfonso VI. of Castile (* 1037; † 1109)

- Konstanze (* 1066; † 1094) ⚭ 1086 Duke Alain IV. Fergent of Brittany († 1119)

- Henry I. Beauclerc (* 1068; † 1135), King of England

- ⚭ 1100 Edith (Mathilde) of Scotland (* 1080; † 1118)

- ⚭ 1121 Adeliza of Louvain (* 1103; † 1151)

Others

- The Bayeux Tapestry, called “Tapisserie de la Reine Mathilde” in France , appears for the first time in 1476 in the inventories of the Bayeux Cathedral . In the 18th century it was wrongly assumed that it was dedicated to Queen Mathilde, the wife of William the Conqueror. It is not a carpet in the true sense of the word, but rather an embroidery on a 70 meter long and 50 centimeter wide canvas. But the tapestry was certainly commissioned by Bishop Odo von Conteville , Wilhelm's half-brother, around 1077 in an English embroidery for the choir of the new cathedral in Bayeux.

- On the site of the Battle of Hastings, Wilhelm had the Battle Abbey built during his lifetime to commemorate the victims of the battle. The small town of Battle gradually developed around the monastery . The remains of the abbey now serve as an (open-air) museum about the Battle of Hastings.

- In 1522, Wilhelm's bones were removed from the coffin. Their length suggested that he must have been about 175 cm tall. The grave was destroyed during the French Revolution , so today only the tombstone and a femur remain in the grave. Victorian historian EA Freeman believed that the femur was lost in 1793.

- In his pamphlet Common Sense , published in 1776, the English-American writer Thomas Paine questioned the divine right of the English kings with a sarcastic reference to the descent and the way in which William the Conqueror came to power: “A French bastard who lands with an armed bandit and proclaiming himself King of England against the will of the locals, simply put, has only a very shabby villainous origin. There is certainly nothing divine about this. "

swell

- Roger AB Mynors et al. a. (Ed.): Willemi Malmesbirensis Monachi de Gesta Regum Anglorum . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1998–1999, ISBN 0-19-820678-X and ISBN 0-19-820682-8

- Ralph H. Davis (Ed.): The Gesta Guillelmi of William of Poitiers . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1998, ISBN 0-19-820553-8 .

- Marjorie Chibnall (Ed.): The ecclesiastical history of Orderic Vitalis ("Orderici Vitalis Ecclesiasticae Historiae Libri Tredecim"). Clarendon Press, Oxford 1980-1986

- General introduction, book I and II . 1980

- Book III and IV . 1983

- Book V and VI . 1983

- Book VII and VIII . 1983

- Book IX and X . 1985

- Book XI, XII and XIII . 1986

- David N. Dumville (Ed.): The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. A collaborative edition ("Chronicon Saxonicum"). Brewer Books, Cambridge 1983-2004 (10 volumes)

- Elizabeth M. VanHouts (Ed.): The gesta Normannorum ducum of William of Jumièges, Orderic Vitalis and Robert of Torigui . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1992 ff.

- Introduction and book I-IV . 1992, ISBN 0-19-822271-8

- Books V-VIII . 1995, ISBN 0-19-820520-1

literature

- David Bates: William the Conqueror. Yale University Press, New Haven 2016, ISBN 978-0300118759 . [current standard work]

- David C. Douglas : William the Conqueror . Hugendubel, Kreuzlingen 2004, ISBN 3-424-01228-9

- Kurt-Ulrich Jäschke: The Anglo-Normans . Stuttgart 1981, ISBN 3-17-007099-1

- Kurt Kluxen : History of England. From the beginning to the present (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 374). 5th enlarged edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-520-37405-6 .

- Philippe Maurice : Guillaume le Conquérant. Flammarion, Paris 2002, ISBN 2-08-068068-4

- Jörg Peltzer : 1066. The fight for England's crown. CH Beck, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-69750-0 .

- Marco Innocenti : William I the Conqueror. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 22, Bautz, Nordhausen 2003, ISBN 3-88309-133-2 , Sp. 1544-1550.

Web links

- http://gutenberg.org/etext/1066

- http://englishmonarchs.co.uk/normans.htm

- William I in the database of Find a Grave (English)

- http://historyhouse.com/in_history/william/

- http://chateau-guillaume-leconquerant.fr/

- Literature about Wilhelm I in the catalog of the German National Library

- [1]

Remarks

- ↑ See Jörg Peltzer: 1066. The battle for England's crown. Munich 2016, pp. 94–96.

- ↑ Jörg Peltzer: 1066. The fight for England's crown. Munich 2016, p. 172f.

- ^ Kurt-Ulrich Jäschke: The Anglo-Normans. Stuttgart 1981, p. 108f .; Lexicon of the Middle Ages . Vol. 3. Munich / Zurich 1986, Sp. 1180.

- ^ Kurt-Ulrich Jäschke: The Anglo-Normans. Stuttgart 1981, p. 109.

- ↑ Lexicon of the Middle Ages . Vol. 3. Munich / Zurich 1986, Sp. 1180.

- ↑ Lexicon of the Middle Ages . Vol. 3. Munich / Zurich 1986, Sp. 1178f.

- ^ A. Harding: Hundred Rolls . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 5, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1991, ISBN 3-7608-8905-0 , column 218 f.

- ↑ Thomas Paine: Common Sense. § 3 Of the monarchy and succession, nos. 59, 60 . ( Memento of the original from December 16, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 910 kB), p. 19 of the German translation in the portal liberliber.de , accessed on November 23, 2012

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Harald II |

King of England 1066-1087 |

Wilhelm II. |

| Robert I. |

Duke of Normandy 1035-1087 |

Robert II. Curthose |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Wilhelm I. |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Wilhelm the conqueror; Wilhelm the Bastard; William the Conqueror (English); Guillaume le Conquérant (French) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | King of England and Duke of Normandy |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1027 or 1028 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Falaise , Normandy , France |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 9, 1087 |

| Place of death | Saint-Gervais Monastery near Rouen , Normandy, France |