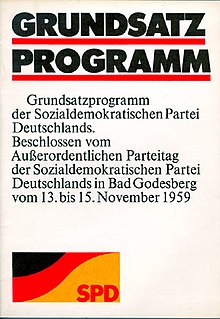

Godesberg program

The Godesberg Program was the party program of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) from 1959 to 1989 . An extraordinary SPD party conference in the town hall of Bad Godesberg , today a district of Bonn , passed it with a large majority on November 15, 1959. This basic program expressed the change of the SPD from a socialist workers' party to a people 's party . Central elements of the Godesberg program are still valid today - these include the commitment to the market economy and national defense , the formulation of basic values and the claim to be a people's party. The Berlin program followed the Godesberg program in December 1989 .

prehistory

Changes since 1925

The Heidelberg program of 1925 was binding for the SPD as a basic party political program until the end of the 1950s. Since its adoption in the middle phase of the Weimar Republic , serious political upheavals had taken place in Germany and Europe: the failure of the first German republic, the rise and rule of National Socialism , World War II , division of Germany and Europe, the Cold War , Stalinism and the expansion of communism . The authors of the Heidelberg program could not foresee these upheavals; they expected a socialist future. Even more: In many respects this program was little more than a new edition of the Erfurt program that had been drawn up after the Socialist Act in 1891 came to an end . The formulation of a revolutionary perspective stood alongside contemporary reform demands .

Policy of the SPD under Kurt Schumacher

Kurt Schumacher , until his death in August 1952 the undisputed leader of the SPD in the western zones and in the early years of the Federal Republic, always rejected discussions about a new basic program as out of date. What the social democracy wants in principle, "is clear to us all" - so Schumacher. More important to him was the formulation of a clear alternative to government policy, especially in the fields of Germany and foreign policy .

Schumacher was a sharp opponent of alliances with communists. His Weimar experience with the anti-parliamentarianism of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and the compulsory unification of the SPD and KPD to form the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) in the Soviet occupation zone motivated him to adopt this stance. Nevertheless, Schumacher's thoughts and speeches were shaped by the concepts of Marxism , to which he attached great importance as an instrument for analyzing society. For him - as for many social democrats - socialism as a form of society and socialization as a way to achieve it were on the agenda after the experiences of the Third Reich and the Second World War. At the same time, after 1945 he emphasized the ideological openness of his party. In particular, he called on people who affirmed socialism out of Christian convictions to see the SPD as their political sphere of activity. In Schumacher's eyes, the SPD played the leading role in economic and political reconstruction, all the more if it succeeded in attracting white-collar workers, civil servants, small traders, craftsmen and farmers in addition to the workers.

As chairman of the party, Schumacher shaped the affirmation of parliamentarism and the state within the party as well as the unconditional insistence on internal and external freedoms for Germans. The latter brought him and the SPD into opposition to the federal government. He accused her of giving up the political goal of national unity of the Germans in favor of a connection to the West for West Germany. He rejected common political institutions in Western Europe such as the Council of Europe as “conservative, clerical, capitalist and cartelist”. Overall, he shaped the image of sharp opposition by the SPD to important political decisions in post-war Germany.

Federal opposition

The Federal Republic of Germany, founded in May 1949, experienced a period of rapid economic reconstruction in the 1950s, known as the economic miracle , and a policy of increasing ties to the West, which was promoted by the governments under Chancellor Konrad Adenauer . At the federal level, the Union parties dominated , i.e. the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the Christian Social Union (CSU).

Since the first federal election , in which it had expected a victory, the SPD had been relegated to the opposition bank in the German Bundestag , while it provided the government in the city-states of Berlin , Hamburg , Bremen and some large states . The second federal election in September 1953 also turned out to be disappointing from the perspective of the Social Democrats - the SPD suffered slight percentage losses and remained an opposition party, while the CDU and CSU recorded significant gains in voters. In response to these circumstances, deliberations on the formulation and adoption of a new party program intensified.

Programmatic preparatory work

Declaration of Principles of the Socialist International

In smaller circles and with little attention from the party as a whole, program discussions began in the early 1950s. In many cases, the participants referred to the declaration of principles of the Socialist International , which had been founded in Frankfurt am Main in 1951 and which had offered the European socialists a programmatic orientation for the first time after 1945. The preamble to the resolution on the “goals and tasks of democratic socialism ” expressed clear criticism of capitalism and distinguished the socialists from the communists . Furthermore, she emphasized the different motivations of the individual for the support of socialist ideas - Marxist or other justified social analyzes, religious values and humanistic considerations were of equal importance here. After all, she maintained that democracy would develop its highest form under socialism, and that socialism could only be realized through democracy. However, this declaration of principle was denied a major all-party echo in the SPD.

Dortmund action program from 1952

Under the leadership of Willi Eichler , who had been campaigning for a programmatic renewal of the SPD for a long time, a ten-person committee set up by the party leadership worked out the draft of a so-called action program from April 1952. In September of the same year, the SPD's Dortmund party congress unanimously adopted this draft as the Dortmund action program . The background to this was the upcoming election campaign for the federal election, which was to take place a year later. From the point of view of the party officials, the first draft had barely met the requirements of the election agitation and was therefore considerably modified in form and content before the party congress. But even the adopted version had - according to the historian Kurt Klotzbach - only the "character of an honorable testimony to meticulous practical self-understanding". It did not arouse external impact or interest in the public. The moderate reform demands of the party in the actual program of action were also unrelated to the apodictic and critical description of the present in the foreword, which Kurt Schumacher had written, who had died in August 1952. All attempts that the party undertook after 1952 to make the Dortmund action program known and popular - these included specialist conferences, its own series of publications and a handbook of social democratic policy that extensively commented on the program - remained without the desired success. The Dortmund action program only reached those functionaries who were firmly committed to the party even without such a paper.

Berlin version of the action program from 1954

After the defeat in the Bundestag election of 1953, the party leadership around the new chairman Erich Ollenhauer intensified efforts to formulate a new party program. Initially, a study commission worked out the so-called Mehlemer theses by April 1954 . These were then used by a commission of 60 people, again chaired by Willi Eichler, to revise the Dortmund action program for the Berlin party congress of July 1954 and to give it a preamble. The party congress approved this update and addition. Socialism was referred to as the "goal of humanity". However, it is not an end goal, but an ongoing task. Furthermore, socialist ideas are not a “substitute religion”. Christianity , classical philosophy and humanism were considered to be the roots of the socialist world of thought. The SPD's turning away from the pure workers' party towards the people's party was already stated in this party congress resolution of 1954: “Social democracy has become a party of the people from a party of the working class , as which it was founded. The workforce forms the core of its members and voters. ” Karl Schiller had a decisive influence on the economic policy section of the program . His catchy formula “As much market as possible, as much planning as necessary”, coined a year earlier, introduced the subsection on “Planning and competition”. The SPD thus reversed its appreciation of planned and market economy principles; from now on the market had priority over planning. Socialization was no longer discussed in the action program. It only demanded the transfer of the basic industries into common ownership with the aim of full employment .

Draft policy and organizational reform

One of the results of the SPD's Berlin party congress in 1954 was the decision to set up a commission to draft the new party program. This "large program commission", made up of 34 people, took up its work in five sub-committees and was also controlled by Willi Eichler in March 1955. The program work made slow progress at first. A first point of contention was the question of whether or not the basic program should be initiated by a so-called "time analysis". The task of such an analysis would have been the description of society and the present from the perspective of the party, as well as a historical-philosophical prognosis. The discussion about it was tough and sometimes tiring even those involved. Aspiring party politicians such as Herbert Wehner , Fritz Erler and Willy Brandt held back during this phase of program development. Instead, they concentrated on preparing important organizational and personnel changes. The aim of these plans was to remove the influence of the “office”, ie the party apparatus of the full-time functionaries of the party executive. The reformers in the party strove to assign the necessary administrative tasks to the “apparatus” alone. The party leadership itself should formulate the political direction. This change was achieved at the Stuttgart party congress in May 1958. The influence of the full-time paid declined due to the decision to elect the so-called Presidium as the center of the party leadership from among the party executive committee. Wehner and Waldemar von Knoeringen were also elected as Ollenhauer's deputies . As early as October 1957, the reformers in the SPD had achieved a stage victory. In the new election of the executive board of the SPD parliamentary group in the Bundestag , three of their most prominent leaders prevailed: Wehner, Erler and Carlo Schmid replaced Erwin Schoettle and Wilhelm Mellies , who were considered traditionalists, in the post of deputy parliamentary group leaders and henceforth determined the basic lines of the parliamentary group's work.

One of the reasons for these decisions at the Stuttgart Party Congress was the preparatory work by the reformers. More important, however, was the shock caused by the result of the 1957 federal election . The Union parties won an absolute majority. Adenauer's popularity was unbroken. Shortly before, he had succeeded in reintegrating the Saarland into the Federal Republic. In addition, the pension reform proved to be an effective electoral move. The Chancellor also knew how to interpret the suppression of the Hungarian uprising against the SPD. From the SPD's point of view, all of these factors had a negative effect and gave it a result of almost 31.8 percent of the vote. In the leadership circles of the SPD pessimistic future expectations were circulating. Due to the dominance of the Union, the Federal Republic is heading towards a one-party state following the example of George Orwell's novel 1984 . Hamburg Social Democrats considered the "danger of the clerical semi-fascist state" to be given. Domestic political fascization threatens . The lasting impact of this election result increased efforts to present a new policy program.

Eichler had compiled a first overall draft from the drafts of the sub-commissions in April 1958 and presented it to the party congress. In the summer, this draft, which was discussed in the first reading in Stuttgart, was sent to all party members. A broad internal party discussion process then began with an intensity that surprised many in the party leadership. The interest reached out for the first time through the circle of the few who had dealt with program issues for years. In particular Eichler and Heinrich Deist , a pioneer of updated economic policy principles of the SPD, discussed the draft at several hundred party events with the members. Many comrades at these meetings expressed their dissatisfaction with the length of the text. For this reason, the party executive , which now took over the reins of the program discussion, set up a so-called editorial committee in February, headed by the journalist Fritz Singer . This shortened the draft presented by Eichler significantly. At the same time, it removed - as it was said - "verbally radical remnants". In addition, the controversial time analysis has been dropped. In June 1959, Sänger submitted the revision to the party executive. Four people - Eichler, singer, Ollenhauer and Benedikt Kautsky , son of Karl Kautsky - then refined the design again. Legal expert Adolf Arndt integrated a clearer commitment by the party to the Basic Law , while Erler, an expert on military issues, added a statement on national defense. The deleted time analysis was replaced by an introduction written by Singer and Heinrich Braune . The party executive decided on September 3, 1959, to present the current version at the Godesberg extraordinary party congress of November 1959.

Godesberg Party Congress 1959

The extraordinary party congress of the SPD, which met in the town hall of Bad Godesberg from November 13 to 15, 1959, dealt exclusively with the question of a new basic program. Ollenhauer opened the party congress in front of 340 delegates with voting rights and 54 functionaries present in an advisory capacity, making it clear that the new program had no scientific claims but should be understood as a political program of a political party.

At the beginning of the debate, the question arose whether the decision on the draft program should be postponed. A request from party congress delegates from Bremen demanded such a postponement because there was not enough time until the party congress to discuss the last draft of the party executive in detail. This motion did not find a majority.

In the course of the party congress it became clear that the critics of the draft, who found themselves on the left wing of the party, were clearly in the minority and were also divided. Two items in the new program generated more intense debate. For one, a number of delegates called for changes to the section on “Property and Power”. The local association Backnang demanded the transfer of key industries into common ownership - 69 delegates at the party congress approved this request. 89 delegates voted in favor of the application of the district of Hessen-Süd, which only wanted to see the protection of private property enshrined if this protection did not hinder a fairer social order. On the other hand, the new version of the relationship with the churches sparked a major controversy. The new program spoke of a “free partnership”. That went too far for many delegates. Many members and officials have traditionally had a tense relationship with the churches and their representatives. In addition, quite a few Social Democrats were involved in freethinking associations . Only the appeal to unity of the party saved the party executive from defeat on this issue.

Changes to the draft of the party executive committee were only made in details. An editorial committee headed by Fritz Sänger incorporated these details. On November 15, the party congress passed the draft program with 324 votes to 16. This result is particularly attributed to the commitment of two people. Herbert Wehner strongly advocated the adoption of the new basic program. One should say goodbye to Marxist ideas. In this context he used his famous incantation “Believe a burned!” Several times. The left of the party surprised Wehner's position, as they thought he would be among the critics of the draft program before the party congress. Ollenhauer was also a decisive factor. Out of loyalty to the party chairman, many delegates approved the program, even if they did not agree with all points.

content

introduction

The Godesberg program is divided into seven parts, preceded by an introduction. This addresses the "contradiction of our time", which would consist in making the civil use of nuclear power possible, but at the same time being exposed to the risk of nuclear war . Democratic socialism strives for a “new and better order”. It should give everyone in peaceful conditions a fairer share of the common wealth.

Core values

The first section is devoted to the so-called “basic values of socialism” - freedom, justice and solidarity. Democratic socialism has three roots in the history of ideas : Christian ethics , humanism and classical philosophy. There is no reference to a further root, Marxism, although this root had played the decisive role in all of the previous basic programs. The SPD, according to the Godesberg program, does not want to proclaim any “ultimate truths”, the bond that unites the party are the basic values and the common goal of democratic socialism. Socialism is not the ultimate goal of historical developments, but the constant task of “fighting for freedom and justice, preserving them and proving oneself in them”.

Basic demands

The second section presents “basic requirements”. War is rejected as a means of politics. An “international legal order” should regulate the coexistence of peoples. Communist regimes are rejected because socialism can only be achieved through democracy. Democracy is not only endangered by communists. Every power, including economic power, must be publicly controlled; if this does not happen, democracy is also at risk. For this reason, democratic socialism strives for a new economic and social order.

Statements on the state order and national defense

With the third section of the Godesberg program, the SPD expressly committed itself to the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany. From this the advocacy of the national unity of the Germans derives and at the same time the commitment to national defense. In this context, a nuclear weapon-free zone in Europe and steps towards disarmament were called for.

Economic and social order

The fourth section, which deals with the “economic and social order”, is the longest. The Schiller's formula "competition as far as possible, planning as necessary!" Was included in the program and shaped the statements on the economic and social order. A steady economic upswing and the chance of general prosperity for all would be ensured by the second industrial revolution . The task of state economic policy is to realize these opportunities for prosperity through a forward-looking economic policy on the basis of national accounts and a national budget. However, further influences on the market would have to be avoided because "free competition and free entrepreneurship [are] important elements of social democratic economic policy". If private economic power threatens to become a threat to competition and democracy, public scrutiny through investment controls, through antitrust laws and through competition between private and public service companies is required. Only if a “healthy order of economic power relations” cannot be guaranteed, common property is justified. The Godesberg program does not speak of socialization. The demand for the socialization of mining , made by the party a year earlier in view of the incipient mining crisis in Germany, was also not found in this section of the program. There must be effective participation within the companies . The democratization process should not stop at the companies. Here, too, there must be more opportunities to participate: "The employee must turn from an economic subject to an economic citizen" - so the program. Social policy has to create the basis for the free and independent development of the individual .

Cultural life

The fifth section deals with “cultural life”. The statements in this part of the program primarily served to change the relationship between the party and the churches. In the interaction of these institutions, "mutual tolerance" from the position of a "free partnership" is required. The program also puts it briefly: "Socialism is not a substitute for religion."

International community

In the sixth section, the party presented its ideas about the "international community". In doing so, she took up demands that she had been making for decades. Securing freedom and maintaining peace are the primary goals here. These included the demand for general disarmament and international arbitration tribunals. The United Nations should become an effective guarantor of peace. In addition, developing countries are entitled to solidarity and unselfish help from richer peoples.

Review and perspective

In the final section with the heading Our Way , we first look back at the history of the labor movement . Formerly the “object of exploitation of the ruling class”, the worker had won his recognized place as an equal citizen over the decades. The struggle of the labor movement was a struggle for freedom for all. For this reason, social democracy has "turned from a party of the working class into a party of the people". The task of democratic socialism is not yet fulfilled, however, because the capitalist world is not in a position to "oppose the brutal communist challenge with the superior program of a new order of political and personal freedom and self-determination, economic security and social justice" and at the same time the To consider emancipation aspirations of the developing countries. The “hope of the world” here is democratic socialism, which strives for a “humane society”, “free from need and fear, free from war and oppression”.

Alternative drafts

Design by Wolfgang Abendroth

Wolfgang Abendroth , one of the few West German Marxists with a professorship at a university ( Philipps University of Marburg ) in the post-war years , tried to force the party to maintain basic Marxist positions. For this reason he took part in the debates on a revision of the basic program. After working on the program committees for six years, he sent Eichler a counter-draft on April 15, 1959. This was fundamentally based on the positions of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels .

Even with the first chapter of his alternative draft, Abendroth marked the essential difference to the later Godesberg program. This chapter - called "The social situation in the capitalistically organized part of the world" - was based on the continuing monopoly and concentration of capital . A small group of capitalists and managers appointed by them direct the physical and mental work of the majority of the population. Claims of this majority for equal participation in the control of the “social work process” would be successfully fended off by this power group, as well as all demands for full participation in material and cultural progress. The amalgamation to finance capitalist blocs and the tendency towards monopoly as a whole prevented attempts at democratic control. Rather, the state merges with the interests of this overpowering group of capitalists. Public authority can therefore always be placed in the service of their special interests.

A change in this situation can only be hoped for if the “struggle of the workers” to defend and improve their living conditions and to introduce the socialist mode of production is extended to the “struggle for state power”. According to Abendroth, the Basic Law in no way precludes the peaceful transition to socialism. The “mobilization of the working class” is necessary for this. Such an approach had prospects if the class relations in society and in the political system of the Federal Republic were worked out analytically and communicated to the masses. Enlightenment of the masses about the real class structures is sabotaged by manipulatively acting party leadership in the SPD.

Abendroth's alternative proposal was hardly echoed within the party. Only the sub-district of Marburg and the local association from Senne referred to him. The party congress did not discuss the relevant proposals. Abendroth himself had not been able to get a mandate for the Godesberg party congress.

Counter-draft by Peter von Oertzen

Another counter-proposal came from Peter von Oertzen , also a representative of the left wing of the party. On November 8, 1959 von Oertzen informed some party friends that he had designed an alternative draft. He deliberately designed this as a compromise, with which he wanted to iron out "the worst corners" of the executive board's draft. Abendroth's alternative proposal was known to him, but he rejected it. In terms of content, the Abendroth draft was correct, but the form, train of thought and argumentation were too dogmatic for him.

Peter von Oertzen insisted on the traditional triad of freedom, equality, and brotherhood . This is preferable to the new triad of basic values “freedom, justice, solidarity”. Von Oertzen did not remove Schiller's formula of the primacy of the market over planning. He did, however, set up a catalog of socialization for a number of industries. Energy-generating companies, especially in the nuclear industry , the coal and steel industry , large chemical companies, large banks , insurance companies and dominant companies in other sectors are ripe for appropriate measures. In addition, von Oertzen formulated a section on the democratization of the economy .

Oertzens' initiative came too late to be considered in the deliberations of the party congress. His speech did not cause any change of opinion in the majority of the delegates. Peter von Oertzen remained one of the 16 delegates who refused to vote for the Godesberg program.

Reactions and effects

Reactions from leading SPD politicians

Many leading politicians in the SPD expressly welcomed the new basic program. Willy Brandt, for example, considered it a “contemporary statement” that promoted the party's practical work. It is more difficult for the opponents of the SPD to attack them with distorting statements instead of seriously dealing with social democracy. The basic program also portrays the SPD as a “militant democratic freedom movement”. In addition, clarifications had been made on a number of important points, for example in relation to the churches, the state and national defense. Willi Eichler emphasized and welcomed the fact that basic values had been expressly formulated and that freedom played the central role among them. Carlo Schmid pointed out that according to the Godesberg program, socialism was no longer a worldview and certainly no longer a substitute religion. Although there are still classes, class struggle is no longer necessary, because the state brings about a balance between class interests. Erler particularly welcomed the changed relationship with the churches and that some things from the 19th century had been "cleaned up".

Internal party criticism

Intra-party criticism remained the exception and was limited to the small circle of traditionally argued Marxists. Abendroth, for example, disliked the detachment from traditional Marxist basic ideas. A critical analysis of society and the state will be completely dispensed with in the new program. Central “laws of movement and contradictions” therefore remained hidden, and with it the starting points for the “objectives, strategy and tactics of the party”. The SPD is turning away from its educational task, its duty to promote class consciousness .

Peter von Oertzen also kept his distance from the new program. It aligns the party “unilaterally to the parliamentary debate”. It blurs “the class situation and the class interests of the workforce”, in this context the offers to the self-employed middle class are also “questionable”. In addition, von Oertzen pointed out that the program as a whole was supported by a hardly justified economic optimism. "The authors basically do not believe in the possibility of serious economic setbacks" - said von Oertzen.

Reaction of the CDU and the FDP

The CDU predominantly claimed that the SPD's new basic program was just a maneuver to camouflage true intentions. The strategic goal of a “Marxist seizure of power” is unchanged. In the Godesberg program, great leeway had been left for extensive regulation of the economy and society. However, the Union was concerned about the SPD's offer of tolerance and partnership to the churches. The Union therefore advised the churches not to forget the allegedly anti-Christian attitude of social democracy. Some Christian Democrats intervened with clergy so that SPD advertisements would not appear in church newspapers . In 1960, at the CDU party congress in Karlsruhe , a dispute broke out between Adenauer and Eugen Gerstenmaier , then President of the Bundestag . This advised the delegates to examine the similarities between the SPD and CDU in social, social and economic policy on the basis of the SPD's new program. Adenauer responded with clear words. He considered the SPD program to be a pure diversionary maneuver and contradicted all ideas about a common policy.

The Free Democratic Party (FDP) considered the SPD's stance on state order and national defense to be steps in the right direction. On the other hand, she saw the economic policy considerations of the Godesberg program as a “camouflaged socialization bomb”. An SPD government will not shy away from touching the private property of its citizens.

Echo in leading newspapers

The Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) noted that the SPD had removed a number of blockades that blocked the way to the voters. A change from the workers' party to a party for workers is recognizable. The FAZ, however, remained suspicious of the economic policy statements of the Godesberg program. Central economic control attempts cannot be ruled out by an SPD government. Even the world pointed out that the economic section of the program could be a lot of leeway. However, she also saw a clear rapprochement between the party and the state, church, army and the market economy in the other program statements. The Frankfurter Rundschau , especially Conrad Ahlers , did not criticize the openness of the economic policy statements. There does not have to be final clarity here, what is more important is that the spirit of the times is hit. The SPD does not want to overturn the existing order, but rather to transform it into a defensive social democracy.

The SPD on the way to power

The programmatic reorientation of the party was one factor that contributed to the changed public perception of the SPD. It was seen less and less as an implacable opposition party. The patriarchal, representative, popular and occasionally non-partisan appearance of leading social democrats in the countries, which included Max Brauer , Wilhelm Kaisen , Hinrich Wilhelm Kopf , Georg-August Zinn and Willy Brandt, supported this impression.

The rapprochement with ethical Protestants already succeeded in the common commitment against rearmament and in the fight against atomic death . The fact that Protestant Christians from the bourgeoisie could see the SPD as their field of activity was demonstrated by the party entries of Gustav Heinemann , Johannes Rau and Erhard Eppler , who came from the All-German People's Party . The long-awaited break in the milieu of the Catholic workforce took place only gradually. In the Ruhr area, the crisis in the iron and steel industry that began in the mid-1960s was necessary for this.

At the federal level, the SPD decided not to position itself as an uncompromising opponent of the governing parties, but as a “better party”. She made a point of highlighting similarities with the government and spoke of her community policy. A first milestone in this development was Wehner's sensational foreign policy speech to the Bundestag on June 30, 1960, in which he formulated the SPD's change of course in foreign, German and alliance policy. The SPD ended the ongoing conflict with the government here. From then on, she tolerated and supported the Federal Republic's ties to the West. The party drew clear boundaries to the left by separating from the Socialist German Student Union in 1961 . Exclusions of prominent leftists from the SPD also signaled the dividing line from Marxism. Wolfgang Abendroth, his academic colleague Ossip K. Flechtheim and Viktor Agartz , an influential trade unionist for many years, were affected by such resolutions . As early as February 5, 1960, the SPD executive board had decided to support other student associations, "if they recognize the SPD's Godesberg program." On May 9, 1960, the Social Democratic University Association (SHB) was founded with the support of the SPD . who, unlike the SDS, explicitly committed to the Godesberg program.

In the 1960s, the SPD's share of the vote in federal elections grew steadily. The core of the electorate continued to be workers. The party also lastingly reached other sections of the population. The assertion of the Godesberg program that the SPD had become a people's party could more and more be derived from its electoral structure. The political weight of the SPD thus increased. In 1966, with the formation of the grand coalition under Kurt Georg Kiesinger, she entered the government. In 1969, with the formation of the social-liberal coalition under Willy Brandt , it relegated the Union parties to the opposition bench, and in the 1972 Bundestag election it finally drew more votes than the Union.

Programmatic additions and updates

Discussions until the late 1960s

In the 1960s, program discussions were of little importance overall. The party supplemented the main statements of the Godesberg program for some policy areas. The most important additions related to education policy , legal policy and Germany policy. In 1964, the party leadership outlined its ideas for educational reform in the 1960s and 1970s with its “Education Policy Guidelines” . In 1968 the SPD party congress in Nuremberg passed a "legal political platform". The party called for the restriction of political criminal law, emphasized the idea of rehabilitation and crime prevention and campaigned for a reform of the judiciary that should make it more transparent and efficient. The party looked for new ways in Germany and Ostpolitik . The trigger was the shock caused by the construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961 . The non-recognition of the GDR should be overcome as well as the rejection of the Oder-Neisse border as the German eastern border. In 1968 the SPD party congress in Nuremberg approved the “Social Democratic Perspectives in the Transition to the Seventies”. The experiences made in the government, the more recent SPD concepts for the various political areas and the expected future prospects should be summarized in this paper on the basis of the Godesberg program statements. However, this synthesis did not acquire any greater importance, because practical questions of politics - these included the debate about the emergency laws, approval of the grand coalition and the relationship with the German Trade Union Confederation - dominated the discussion. For the left, which became more articulate again at the end of the 1960s, the “perspectives” also led in the wrong direction. For the pragmatists, on the other hand, the degree of societal analysis found in the “Perspectives” went too far.

Orientation frame 85

The 1970s saw intensive program discussions that spread to the party. The SPD endeavored to develop a medium-term political concept for the next 10 to 15 years. The first draft of the so-called orientation framework , developed since the early 1970s under the direction of Helmut Schmidt , Hans Apel and Jochen Steffen , fell through in 1973 within the party. The Jusos and representatives of the party left criticized the lack of a socialist perspective.

A new commission, which was considerably enlarged to 30 people, chaired by Peter von Oertzen, developed a second draft. Schmidt and social democrats like Hans-Jochen Vogel , who organized themselves in the “Godesberg Circle”, warned against changing the programmatic foundations. They feared a narrowing and dogmatization of the theoretical basic assumptions of the SPD - a clear indication to the party left not to overdo it with the revitalization of Marxist positions. The party leadership, especially Wehner and Brandt, made these warnings their own and knew that the party majority was behind them. The commission around Peter von Oertzen took these signals into account and tried a middle ground. The Godesberg program should not be revised, but a one-sided, free-market reading of the program, as prevailed in the 1960s, was also considered inappropriate.

In November 1975, the second draft of the Orientation Framework 85 was finally adopted by party congress resolution in Mannheim . At the party congress there were lengthy debates about the positions on "market and control". The party left disagreed with the corresponding section of the orientation framework and submitted applications for investment control , investment bans and the socialization of means of production. After this demonstrative expression of displeasure, which did not change anything in the draft, she also approved the draft presented, which was passed with only two abstentions and one vote against.

The orientation framework did not achieve a status that would guide action, because the economic framework conditions deteriorated to such an extent that even the trimmed growth expectations of the orientation framework became waste . Within the party he was soon forgotten. Only the process of creating the orientation framework remained positive in many of the participants. The party left and the party right had been able to agree on a presentable compromise in a largely objective dispute.

Berlin program from 1989

At the end of the 1970s, Brandt, as party leader, refused to take steps to formulate a new program to replace the one in Bad Godesberg. In 1982, however, he announced that the party would go into a phase "in which we critically tap Godesberg." The Basic Values Commission at the SPD party executive presented a report on this two years later. It contained a number of recommendations as to which further aspects should be included in a new basic program and which passages of the Godesberg program should be specified. Accelerated technological change , the serious rise in unemployment , problems of environmental degradation , the international debt crisis, the arms race and the emergence of new social movements demanded new answers. A first draft was presented in 1986. It aroused sharp criticism from left-wing Social Democrats.

A second commission, headed by Oskar Lafontaine , presented a revised draft in March 1989, which became the basis for the party congress that met in Berlin from December 18 to 20. This party congress adopted the SPD's new basic program , the Berlin program . Ecological questions and demands, the appeal for a sustainable orientation of the industrial society , the striving for equality of women and the demand for a new role relationship between the sexes, the extension of solidarity to future generations, the will for an extended participation of the workers in productive assets as well as for expansion - and the restructuring of the welfare state characterized this script. The basic values - freedom, justice and solidarity - continued, also in the Hamburg program of October 2007, also the positioning as the "party of the people". Since the Berlin program, however, the term “left people's party” has been anchored in the basic programs.

Scientific evaluations

Twenty years after its adoption, the magazine Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte said on the importance of the Godesberg program: “No other document by a political party in the Federal Republic has produced such controversial statements and interpretations as this program.” These ranged from strict rejection even in academic evaluations up to comprehensive endorsement.

Adaptation

Those who believed that the main task of the SPD was to help overcome the capitalist social system in (West) Germany largely rejected the Godesberg program.

Historians of the GDR condemned the program and moved along the lines laid out by the SED. In the “technical dictionary of the history of Germany and the German labor movement” it was said that the program demonstrated the “integration of social democracy in the state of developed state monopolitical capitalism”. Even more: the authors claimed that the program “largely corresponded to the policy of monopoly capital”. The "ideological on the bourgeois idealistic philosophy" based text is the "complete turning away from the social democratic goals and traditions in theory and practice".

Abendroth interpreted the program as the end of an adjustment process. The fight against “ oligopolistic capital” had been put on record by the SPD. “ The program replaces concrete social analysis and concrete goal setting with the appeal to 'values' and formulas, which can be interpreted in any way. “According to Gerhard Stuby , the program was the result of a successful policy of“ pro-imperialist forces in the SPD ”. Their objective was the "seamless transfer of the SPD into the state monopoly system of rule".

Ossip K. Flechtheim was also sharply negative. For him, the Godesberg program expressed the "final submission to the restorative development of the Federal Republic". This had already begun in 1914 with the approval of the Social Democrats for the war credits and also showed itself in 1933 in the “pandering to National Socialism”. Theo Pirker wrote off the party after Bad Godesberg, saying that it had ceased to be “an anti-capitalist, socialist or radical democratic party”. The “national socialism” of the Schumacher era has become a “national social liberalism that ideologically made an appendix of the ruling party out of the opposition”.

Tilman Fichter and Siegward Lönnendonker accused the program of completely neglecting the social democratic milieu consisting of youth and cultural associations and of leaving in the dark the question of where additional supporters should be won from.

The “Herford theses” of the Stamokap trend among the Young Socialists rated the program as the loss of the left's last influence on the party organization.

Government ability

The programmatic decisions of Bad Godesberg were welcomed by those authors who measured the development of the party by the extent to which it got involved in the parliamentary system of the Federal Republic and made basic decisions of the post-war development in West Germany - this also includes setting the political course - as its own. In their judgments, these authors were often concerned with exploring the extent to which the Godesberg program succeeded in exhausting and expanding the pool of voters in order to gain government and thus creative power.

Susanne Miller , co-author of a frequently published short story of the SPD , which was also used for internal party training purposes, emphasized that the Godesberg program had “a lot to calm down and clarify within the party, but above all to change the appearance of the SPD in public “Contributed. This created the prerequisite “ to be able to achieve the goal she is striving for: to become a 'people's party' that can be elected by different strata. “Klaus Lompe's judgment was similar. By adopting the program, the Social Democrats gained "a new self-image internally and a new public image on the outside - a prerequisite for their ability to govern". He also emphasized that the Godesberg program was neither a break nor a turning point. Many programmatic lines of discussion of the 1940s and 1950s led to Bad Godesberg, which thus represented "the end of a continuous intellectual development".

Kurt Klotzbach also supported this thesis. In its central statements and demands, the program was "nothing more than a concentration of what leading political and programmatic spokesmen of the SPD had represented on various occasions since the 1940s". The SPD anchored itself through the program “as a liberal-socialist grouping firmly in the pluralistic-competitive democratic system”. The tension between a theory aimed at overcoming the system and a pragmatic, reform-oriented practice, which has determined the history of the party so far, has also been overcome. According to Klotzbach, the goals arose from the basic values, while the means to be selected and tested in each case remained separate from them. Detlef Lehnert disagreed at this point. The tension between theory and practice has by no means been overcome. The SPD only relieved the new program of expectations that were too high. The party's orientation towards basic values and basic demands is "not a priori checkable for its realization in practical politics".

Helga Grebing also emphasized the continuity in which the program had stood. It was not a change of course, "rather, it rewrote the basic guidelines to which the SPD had already worked its way step by step in the decade after the establishment of the Federal Republic." However, it was more than just a keystone. With this text, the Social Democrats had also found a “timely answer” to the “failure of humane socialism in the communist states of Eastern Europe, an answer to the ability of capitalist production relations to shift their existential boundaries, an answer to the emerging changes in the social structure in the Federal Republic". As deficits of the Godesberg program she considered in particular the "blind trust" in the possibilities of economic growth as well as an "unreflected, if not naive euphoria for progress".

Christoph Nonn said that the Godesberg program had "detoxified the social democratic budget of ideas from Marxist elements". Any gaps in the theory that have arisen have been filled "with liberal elements". For practical politics, however, there was little concrete evidence. In his study, Nonn worked out in particular the significance of the crisis in the German coal mining industry, which began in 1958. This had led to considerable controversy within the SPD between representatives of a consistent consumer policy on the one hand and a stringent interest policy for employees, especially miners , on the other. This conflict was not carried out, but suppressed, which is why the Godesberg program did not contain any statements on the socialization of mining, although this old social democratic demand was still party line a year earlier. Subsequently, the SPD avoided taking up conflict-prone issues and promoting them. Instead, in the 1960s, the party concentrated on working on policy areas that were capable of reaching a consensus and gaining opinion leadership there.

In her dissertation on “Consensus Capitalism and Social Democracy”, Julia Angster worked out that the program was also created through intensive engagement with Western, in particular Anglo-American, political and social concepts. The influence of the American trade unions was extremely relevant in this regard. They advocated the John Maynard Keynes- oriented politics of productivity ( overcoming the class conflict through high productivity growth and achieving joint support for a consistent growth policy ), the belief in progress and growth, and pluralism as a social concept. By adapting these concepts specifically in each case, it was not only the SPD who took the path of westernization ; With it, a whole series of Western European workers' movements decided in favor of this reorientation.

attachment

literature

- Helga Grebing : History of the German labor movement. An overview , Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1970.

- Helga Grebing: History of ideas of socialism in Germany , part II, in: History of social ideas in Germany. Socialism - Catholic social teaching - Protestant social ethics. A manual, ed. by Helga Grebing, 2nd edition, VS, Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften Wiesbaden 2005, pp. 353-595, ISBN 3-531-14752-8 .

- Siegfried Heimann : The Social Democratic Party of Germany. In: Richard Stöss (Ed.): Party Handbook. The parties of the Federal Republic of Germany 1945-1980. Volume II: FDP to WAV. With contributions by Jürgen Bacia, Peter Brandt a . a. (Writings of the Central Institute for Social Science Research of the Free University of Berlin , Vol. 39), Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1984, pp. 2025-2216, ISBN 3-531-11592-8 .

- Tobias Hintätze: The Godesberg program of the SPD and the development of the party from 1959–1966. What significance did the Godesberg Program have for the development of the SPD into the ruling party in 1966? , Master's thesis at the Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences at the University of Potsdam , (Potsdam) 2006. ( PDF, 357 kB )

- Kurt Klotzbach : The way to the state party. Program, practical politics and organization of the German social democracy 1945 to 1965. Verlag JHW Dietz Nachf. Berlin / Bonn 1982, ISBN 3-8012-0073-6 .

- Helmut Köser: The control of economic power, in: From politics and contemporary history. Supplement to the weekly newspaper Das Parlament , B 14/74, pp. 3–25.

- Detlev Lehnert: Social democracy between protest movement and ruling party 1848 to 1983 ( edition suhrkamp , Neuesequence, vol. 248), Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1983, ISBN 3-518-11248-1 .

- Sabine Lemke: The role of the Marxism discussion in the development process of the Godesberg program , in: Sven Papcke , Karl Theodor Schuon (Hrsg.): 25 years after Godesberg. Does the SPD need a new basic program? (Series of publications of the university initiative Democratic Socialism, vol. 16), publishing house and mail order bookshop Europäische Perspektiven, Berlin 1984, pp. 37–52, ISBN 3-89025-010-6 .

- Klaus Lompe: Twenty Years of the Godesberg Program of the SPD , in: From Politics and Contemporary History. Supplement to the weekly newspaper Das Parlament , B 46/79, pp. 3–24.

- Christoph Meyer: Herbert Wehner. Biography , Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-423-24551-4 .

- Susanne Miller : The SPD before and after Godesberg (Small History of the SPD, Volume 2, Theory and Practice of German Social Democracy), Verlag Neue Gesellschaft, Bonn 1974, ISBN 3-87831-157-5 .

- Christoph Nonn : The Godesberg program and the crisis in the Ruhr mining industry. On the change in German social democracy from Ollenhauer to Brandt , in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 50th vol. (2002), no. 1, pp. 71–97 ( PDF ).

- Peter von Oertzen: The "true story" of the SPD. On the requirements and effects of the Godesberg program (Pankower lectures, volume 4), Helle Panke, Berlin 1996.

- Hartmut Soell: Fritz Erler. A political biography , Dietz, Berlin, Bonn-Bad Godesberg 1976, ISBN 3-8012-1100-2 .

- Gerhard Stuby : The SPD during the Cold War phase up to the Godesberg party congress (1949–1959) , in: Jutta von Freyberg, Georg Fülberth u. a .: History of the German Social Democracy 1863-1975 , second, improved edition, Pahl-Rugenstein Verlag, Cologne 1977, pp. 307–363.

Web links

- Godesberg program, online ( memento from July 23, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) available on the website of the German Historical Museum (now in the Internet Archive ).

- Godesberg program as a PDF file on the website of the library of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Bonn (1.09 MB)

- Norbert Seitz: Adaptation to reality. The SPD's Godesberg program was adopted 50 years ago . Broadcast by Deutschlandfunk on November 13, 2009.

- November 13, 1959: The SPD party conference in Bad Godesberg begins the summary of the radio podcast by Christoph Vormweg, broadcast on WDR 5 on November 13, 2009.

Individual evidence

- ↑ The assessment that the Heidelberg program is in decisive parts a new edition of the Erfurt program can be found in Miller: Die SPD vor und nach Godesberg , p. 12. Heinrich August Winkler : Workers and workers' movement in the Weimar Republic in detail on the Heidelberg program . The appearance of normality. 1924–1930 , Dietz, Berlin / Bonn 1985, pp. 320–327, ISBN 3-8012-0094-9 . Winkler also emphasizes extensive parallels between the two programs. See pages 321 and 327.

- ↑ Quoted from Heimann: Social Democratic Party of Germany , p. 2047.

- ↑ On the claimed leadership role and the aspired attractiveness of the SPD for social circles beyond the working class, see Heimann: Sozialdemokratische Party Deutschlands , p. 2048.

- ↑ On the importance of Schumacher for the politics and the program of the post-war SPD see Miller: Die SPD vor und nach Godesberg , pp. 9–30. Quote "conservative, clerical ..." from Lehnert: Social Democracy between Protest Movement and Government Party 1848 to 1983 , p. 177.

- ↑ For the declaration of principles of the Socialist International see Grebing: History of ideas of socialism in Germany , p. 438, Klotzbach: Der Weg zur Staatspartei , p. 259 f and Sabine Lemke: The role of the discussion of Marxism in the development process of the Godesberg program , p. 41 f .

- ↑ Klotzbach: Der Weg zur Staatspartei , p. 262.

- ↑ On the Dortmund action program see Klotzbach: Der Weg zur Staatspartei , pp. 260–264 and Grebing: History of Ideas of Socialism in Germany , pp. 438 f.

- ↑ On this Klotzbach: Der Weg zur Staatspartei , p. 320 f and Sabine Lemke: The role of the Marxism discussion in the development process of the Godesberg program , p. 45.

- ↑ Quoted from Grebing: History of Ideas of Socialism in Germany , p. 440.

- ^ Karl Schiller at the economic policy conference of the SPD in February 1953, quoted from Heimann: Social Democratic Party of Germany , p. 2056.

- ↑ For the Berlin version of the action program see Grebing: History of ideas of socialism in Germany , p. 439 f and Klotzbach: Der Weg zur Staatspartei , p. 319-324.

- ↑ On the political fears in SPD circles after the federal election of 1957, see Christoph Nonn: The Godesberger Program and the Crisis of the Ruhr Mining , p. 72 f, citation of Hamburg Social Democrats there p. 73.

- ↑ On the significance of Deist for the Godesberg program, see in particular Helmut Köser: The control of economic power , pp. 8–22 and Christoph Nonn: The Godesberger program and the crisis of Ruhr mining , pp. 79 ff.

- ↑ Information on the development of the program from the Berlin party congress in 1954 to the Godesberg party congress in 1959 at Grebing: History of ideas of socialism in Germany , p. 440 f and Heimann: Social Democratic Party of Germany , p. 2058 f. Thoroughly on this, Klotzbach: The Path to the State Party : Work of the Great Program Commission up to the Stuttgart Party Congress (pp. 433–440); organizational and personnel decisions of the Stuttgart party congress (pp. 421–431); Program discussion at the Stuttgart party congress (pp. 440–442); Program work from the Stuttgart party congress to the party congress in Godesberg (pp. 442–447). For the change at the top of the parliamentary group in October see Meyer: Herbert Wehner , p. 208 f and Soell: Fritz Erler , p. 300–302.

- ↑ Quoted from Gunter Hofmann : Free, but left . In: Die Zeit , 39/1999.

- ↑ On the party congress see Klotzbach: Der Weg zur Staatspartei , p. 448 f and Heimann: Social Democratic Party of Germany , p. 2061. For the tense relationship between Social Democrats and the churches, see Hint: The Godesberg Program of the SPD and the Development of the Party from 1959– 1966 , p. 44.

- ↑ Available online on the website of the German Historical Museum and as a PDF file on the website of the library of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Bonn .

- ↑ The overview of the essential aspects of the Godesberg program is based on Heimann: Social Democratic Party of Germany , pp. 2061–2063.

- ↑ On the then current internal party controversies about social democratic economic policy in the face of the mining crisis, see Christoph Nonn: The Godesberger Program and the crisis of Ruhr mining .

- ↑ On Abendroth's alternative, see Grebing: History of Ideas of Socialism in Germany , pp. 447–449, there also all of Abendroth's quotations.

- ↑ On the alternative proposal by Oertzens see Grebing: History of Ideas of Socialism in Germany , pp. 449–451, there also the quotations from Oertzens.

- ↑ Quoted in excerpts from Klotzbach: Der Weg zur Staatspartei , p. 448 f, note 460.

- ↑ Brandt's assessment by Klotzbach: Der Weg zur Staatspartei , p. 449.

- ^ Evidence for statements by Eichler, Schmid and Erler in Grebing: History of ideas of socialism in Germany , p. 445.

- ↑ On this criticism by Wolfgang Abendroth see Grebing: History of ideas of socialism in Germany , p. 447, there also the Abendroth quotations.

- ↑ On this criticism of Oertzens see Grebing: Ideengeschichte des Sozialismus in Deutschland , p. 450, there also the quotations from Oertzens.

- ↑ For the reaction of the CDU, see back sentence: The Godesberg program of the SPD and the development of the party from 1959–1966 , p. 53 f. The quote on the “Marxist seizure of power” can be found in Hartmut Soell: Fritz Erler , p. 328 and p. 640, note 470.

- ↑ For the reaction of the liberals see the backhand: The Godesberg Program of the SPD and the Development of the Party from 1959–1966 , p. 54, there also the quote.

- ↑ For the reactions from FAZ , Die Welt and Frankfurter Rundschau see the back sentence: The Godesberg Program of the SPD and the Development of the Party from 1959–1966 , pp. 54–56.

- ↑ See Miller: The SPD before and after Godesberg , p. 39.

- ↑ Cf. Lehnert: Social Democracy Between Protest Movement and Government Party 1848 to 1983 , p. 182 f.

- ↑ See Lehnert: Social Democracy between Protest Movement and Government Party 1848 to 1983 , p. 194.

- ↑ On the common policy see Klotzbach: Der Weg zur Staatspartei , pp. 497-532.

- ↑ On Wehner's speech on June 30, 1960, see Meyer: Herbert Wehner , pp. 230–336. Excerpts from the tape recording of this speech in Microsoft Encarta .

- ↑ For the delimitation to the left, see Heimann: Social Democratic Party of Germany , p. 2110 f and p. 2166 f. Information on the exclusion of Flechtheim from Grebing: The history of ideas of socialism in Germany , p. 470.

- ↑ a b Tilman Fichter, Siegward Lönnendonker: Small history of the SDS. The Socialist German Student Union from Helmut Schmidt to Rudi Dutschke , first edition Berlin 1977, pp. 64–70.

- ↑ On the history of the SPD's program in the 1960s, see Heimann: Sozialdemokratische Party Deutschlands , pp. 2069–2072.

- ↑ On the program debate in the SPD up to the Mannheim party congress of November 1975, on the orientation framework itself and on the practical and intra-party significance of the text, see Heimann: Social Democratic Party of Germany , pp. 2075-2085 and Grebing: History of ideas of socialism in Germany , pp. 492– 496.

- ↑ Quoted from Grebing: History of Ideas of Socialism in Germany , p. 556.

- ↑ For the recommendations of the Fundamental Values Commission, see Grebing: History of Ideas of Socialism in Germany , p. 557 f.

- ↑ On the content of their criticism, see Grebing: History of ideas of socialism in Germany , p. 579 f.

- ^ For the Berlin program see Grebing: History of Ideas of Socialism in Germany , pp. 580-584.

- ^ Lompe: Twenty Years of the Godesberg Program of the SPD , p. 3.

- ^ Article "Godesberg Party Conference of the Social Democratic Party of (West) Germany 1959", in: "Subject dictionary of the history of Germany and the German workers' movement". Edited by Horst Bartel, Herbert Bertsch u. a., Volume 1, A – K, Dietz , Berlin (DDR) 1969, pp. 719–721.

- ↑ Wolfgang Abendroth: “Rise and Crisis of German Social Democracy. The problem of the misappropriation of a political party through the tendency of institutions to adapt to given power relations ”, fourth, extended edition, Pahl-Rugenstein Verlag, Cologne 1978. p. 74.

- ↑ Stuby: The SPD during the phase of the cold war up to the Godesberg party congress (1949–1959) , p. 355.

- ^ Ossip K. Flechtheim: The adaptation of the SPD: 1914, 1933 and 1959 . In: Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie , Vol. 17 (1965), Issue 3, pp. 584–604, quoted from Lompe: Twenty Years Godesberger Program of the SPD , p. 8, note 27.

- ^ Theo Pirker: The SPD after Hitler. The history of the Social Democratic Party of Germany 1945-1964 , Rütten & Loening, Munich 1965, quoted from Heimann: Social Democratic Party of Germany , p. 2065.

- ^ Theo Pirker: The SPD after Hitler. The history of the Social Democratic Party of Germany 1945–1964 , Rütten & Loening, Munich 1965, quoted from Grebing, History of the German Labor Movement, p. 247.

- ^ Herford theses . On the work of Marxists in the SPD. Berlin SPW-Verlag 1980, ISBN 3-922489-00-1 , p. 86 ( online ).

- ↑ Miller: The SPD before and after Godesberg , p. 38.

- ↑ Lompe: Twenty Years of the Godesberg Program of the SPD , p. 4.

- ↑ Lompe: Twenty Years of the Godesberg Program of the SPD , p. 9.

- ↑ Klotzbach: Der Weg zur Staatspartei , p. 449 f.

- ↑ Klotzbach: Der Weg zur Staatspartei , p. 599. For details on the tense relationship between theory and practice in the SPD, see ibid., Pp. 25–31.

- ↑ Lehnert: Social Democracy Between Protest Movement and Government Party 1848 to 1983 , p. 191.

- ^ Grebing: The history of ideas of socialism in Germany , p. 443 f.

- ^ Grebing: The history of ideas of socialism in Germany , p. 444.

- ↑ Christoph Nonn: The Godesberg Program and the Crisis of the Ruhr Mining , p. 72.

- ↑ Julia Angster: Consensus Capitalism and Social Democracy. The westernization of the SPD and DGB (systems of order, studies on the history of ideas in the modern age, volume 13). Oldenbourg, Munich 2003, p. 416, p. 424 and p. 428, ISBN 3-486-56676-8 .