Magic spell

A spell is an incantation text that is supposed to produce a certain magical effect. Spells can be assigned to verbal magic . An exact demarcation between the spell and the blessing is not possible. Magic spells belong to the oldest testimonies in German literature, for example the Merseburg magic spells (probably originated in the 8th century) and the “ infernal compulsions ” contained in grimoires . From ancient times there are spells and the like. a. obtained from Marcellus , from Pelagonius , and from Pliny the Elder .

History of the spell

In the pre-Christian, pagan- Germanic early times, magic spells were used "through the power of the bound word to make usable the magical powers that man wants to make himself subservient". In the case of illnesses that were based on a demonic cause, magic spells were used to induce the respective demon to leave the sick person. The spells recorded in the Middle Ages come, at least conceptually, from ancient Roman, Germanic sources and from monks and monk doctors and are mostly influenced or influenced by Christianity. For these medieval magic texts, a classification according to formal, content and functional criteria was developed in incantations and magical salvation blessings. The essential strategies of a) command to demons , b) analogy between world creation, miracle, outstanding historical event and the promise of healing for the sick person as well as c) a story that captivates the sick person (Historiola) offer an overview of the variability of the texts. With recourse to the most extensive German magic spell collection - the corpus of the German blessing and incantation formulas (CSB) with around 28,000 texts - at the Institute for Saxon History and Folklore Dresden, a motif-oriented one was initially created in 1958, later in 2000 one on the mythical-archaic origins and structuralist questions in the sense of Claude Lévi-Strauss . An investigation according to criteria of speech act theory on high medieval sayings from Trier , Bonn and Paris is based on illocutionary strategies. Since most of the medieval magic spells served as verbal therapy by monk doctors and doctors as an accompaniment to a pragmatic medical measure, they were part of an early holistic medicine. On this basis and taking into account their neurobiological factors in limbic and prefrontal areas, the most concise texts were examined from a medical-psychotherapeutic point of view. In modern performing magic , spells are primarily used to distract the audience.

Famous spells

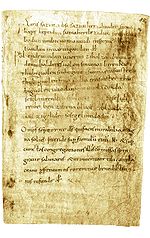

- The Lorsch bee blessing is one of the oldest rhyming poems in the German language. The saying was written in Old High German in the 10th century upside down on the edge of a page of the apocryphal Visio St. Pauli from the early 9th century (today Bibliotheca Vaticana : Pal. Lat. 220 , fol. 58r). The manuscript originally came from the Lorsch Monastery .

- The 10th century worm ban found in the Tegernsee monastery in the Munich library (Clm 18524b), written by a Salzburg hand, with a parallel in the Vienna library, drives the worm (e.g. a deep inflammation) to the surface: “Go out, Nesso, with nine little Nesslein, from the marrow into the vein, from the vein into the flesh, from the flesh into the skin… ”. Parallels were found in ancient Indian magic texts ( Atharvaveda ), so that an Indo-European relationship is assumed. (see also: Wikisource: Old High German Magic Spells)

- The origin of the Merseburg magic spells , which were found in the 9th - 10th centuries, is unknown. They come from a theological collective manuscript from Merseburg, hence their name. In terms of content, the proverbs are about the liberation of a prisoner and the healing of a leg injury.

Famous magic formulas

- Simsalabim goes back with high probability to encounters between medieval Christians and Muslims , who were often described as "magicians" up to the late Middle Ages (also because of the technical and scientific progress of the Islamic world compared to the European world). The bi-smi llāhi r-raḥmāni r-raḥīm (In the name of God, the Most Merciful, the Merciful.) Spoken by practicing Muslims before any meaningful activity was therefore understood onomatopoeically as a conjuring magic formula in popular narratives . ("Simsalabim - and it happened."). The Duden states that the origin of the saying is unclear, but may be traced back to the Latin similia similibus (like with like (to heal), see also magic analogy and homeopathy ). In another opinion, Kalanag touted it as his creation, while other historians ascribe the idea to the Danish-American magician Dante .

- There are different theories for the origin of hocus-pocus :

- In the words of institution of the Christian liturgies (also called the conversion of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ) it says “Hoc est enim corpus meum” (This is my body). It is assumed that the priest's Latin was not understood and that a popular corruption arose: "Now he's doing his hocus-pocus again."

- A sleight of hand in 17th century England was called hax pax max deus adimax "Hocos pokos" after an often used (and insignificant ) spell from the 16th century . The origin of this spell is likely to be traced back to the words of institution.

- Abracadabra is reminiscent of Abraxas and is a magic word already known from the 3rd century, which is supposed to ward off misfortune and illness and to call forth good spirits. In Hebrew , abra ke dabra means "I am created as I will speak".

- ABRAHADABRA the end of words is the word ABRAHADABRA ( Aleister Crowley ) the word of Aeon's Thelema .

- sator arepo tenet opera rotas is a palindrome , written one below the other it forms a magic square .

- The sentence ata gibor le-olam adonai is very often incorporated as the abbreviation AGLA . In Hebrew it says “You God are almighty” and comes from the Jewish eighteen supplication .

- Ciáralo-Báralo , which sounds Italian, is a well-known magic formula in Croatia that may have had a magical meaning in the past, but is now used in children's stories and fairy tales . The sound similarity with the German word "zauber" is striking.

- Lilith's Schem Hammeforasch , the secret name of the gentleman, magic formula.

- mutabor , Latin for “I will be transformed”, is the central magic word in the fairy tale The Story of Kalif Storch by Wilhelm Hauff .

- Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo , was used by the fairy godmother in Cinderella (1950) .

- Bibi Blocksberg hexes with eene meene (in addition to the rare Aberakadabera and once on dam dei ) and the closing formula hex hex .

The effect of magic spells

Questions about the effectiveness of spells that have been used historically are often treated with great skepticism or even with enthusiasm . Therefore, the conditions of form and content of the text and of the situation in which a spell - here healing spell and incantation - was used must be analyzed more precisely. Empirical observations have produced powerful arguments for circulatory and vascular effects; Extreme situations are voodoo conditions with death. As part of the tradition in Europe, the texts have been viewed secretly as a valuable treasure of tradition for more than 1000 years and have demonstrably been consulted by doctors in the High Middle Ages .

For 10–15 years, criteria have been developed on the basis of imaging procedures ( magnetic resonance tomography MRT) and on the basis of the EEG ( electroencephalogram ) with event-related potentials (EKP), which also had to be postulated for brains 1000 years ago. Preconditions for exact conclusions are, however, the assumption of an emergency situation of the patient with hormonally given pressure of expectation to absorb the psychoperformative imagination and a culturally compliant text design, possibly with hypnosis-like practices by shamans , monk doctor or physician.

The following results are evident as brain tissue reactions:

a) The imagery of naming an evil as a demon, e.g. B. in conjuring up the nightmare , transforms horror, fear and tension into negotiable tangible elements by relieving the limbic system and stimulating the cognitively working frontal lobe by means of "labeling emotions " .

b) The wrong-way formulas built into magic spells (e.g. Adynata: “Against colic : There is a tree in the middle of the sea and a vessel full of intestines hangs there, three virgins walk around, two bind, one dissolves” or “I conjure you "Demons, you should eat stones!") Can be seen as an incongruity effect, i. H. tap N400 with EEG as a cognitive surprise potential.

c) With the staging of therapeutic images and word figures, regressions and narratives, cognitive and emotional inner 'libraries' can be stimulated to mobilize resources. This has been successfully tested in modern symbol-related psychotherapies ( hypnotherapy , katathymes picture life , psychodrama, etc.).

d) The induction of formulas of suffering and redemption, especially in medieval evocations of prayer , can contribute to an introversive catharsis with arousal of the middle brain structures and to circulatory changes with an effect on the homeostatic balance as well as the extroversive catharsis with commanding demons for the excitation of lateral and frontal areas of the brain.

With the organic evidence of the brain that shows a neurolinguistic reaction of brain tissue, however, a truly sustainable therapeutic effect for historical communication can only ever be considered possible, not guaranteed.

See also

literature

Sources, editions

- Alf Önnerfors (ed.): Ancient magic spells bilingual . Reclam, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-15-008686-8 (ancient Greek, Latin, German).

- Gerhard Eis : Old German magic spells. Berlin 1964.

- Irmgard Hampp: incantation - blessing - prayer. Studies on magic from the field of folk medicine. Stuttgart 1961 (= publications of the State Office for Monument Preservation Stuttgart. C, 1).

- Otto Schell : Bergische magic formulas. In: Journal of the Association for Folklore 16, 1904, pp. 170–176.

- Elias von Steinmeyer : The smaller Old High German language monuments. Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, Berlin 1916.

- Gustav Storms: Anglo-Saxon Magic. The Hague 1948.

Research literature

- Wolfgang Beck : Magic. In: Gert Ueding (Ed.): Historical Dictionary of Rhetoric Volume 9 St – Z. Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 2009, col. 1483 to 1486 ( with costs Historical Dictionary of Rhetoric Online at de Gruyter ).

- Christian Braun (ed.): Language and mystery. Special language research in the field of tension between the arcane and the profane. (= Lingua Historica Germanica 4). Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-05-005962-4 (for a fee from de Gruyter).

- Wolfgang Ernst : Incantations and blessings. Applied psychotherapy in the Middle Ages. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2011, ISBN 978-3-412-20752-6 .

- Friedrich Hälsig: The magic spell among the Teutons up to the middle of the XVI. Century. Philosophical dissertation Leipzig 1910.

- Jonathan Roper: Spell. In: Rolf Brednich (Ed.) Et al .: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Concise dictionary for historical and comparative narrative research. Volume 14. de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2015, ISBN 978-3-11-040829-4 , Sp. 1197-1201.

- Rudolf Simek : magic spell and magic poetry . In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . tape 34 . de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-018389-4 , pp. 441-446 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wolfgang Wegner: Magic spell. In: Werner E. Gerabek, Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil and Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, pp. 1524–1526.

- ^ Rudolf Simek : Lexicon of Germanic mythology . 2nd, supplementary edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-520-36802-1 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Wegner: Magic spells. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , pp. 1524-1526; here: p. 1524 f.

- ↑ Irmgard Hampp : conjuring blessing prayer . Stuttgart 1961.

- ^ Adolf Spamer : Romanus booklet. Historical-philological commentary on a German magic book . German Academy of Sciences, Berlin 1958 (From his estate, edited by Johanna Nickel .).

- ↑ Monika Schulz : Magic or the restoration of order . Frankfurt 2000.

- ↑ Christa Haeseli : Magical Performativity . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2011.

- ^ Wolfgang Ernst : Conjurations and blessings. Applied psychotherapy in the Middle Ages . Böhlau Verlag, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2011 .; for the approach cf. the review of the medievalist Albrecht Classen in: Mediaevistik. International journal for interdisciplinary research on the Middle Ages. Volume 25, 2012, p. 202 f. ( ac Klassen.faculty.arizona.edu PDF).

- ↑ merseburg.de

- ↑ Cf. Carl Werner Müller : Same to Same. A principle of early Greek thought. Wiesbaden 1965.

- ↑ Lévi-Strauss : Structural Anthropology. I, Paris 1985, (German :) Frankfurt / M. 1981², p. 183.

- ↑ Joachim Telle: Petrus Hispanus in the old German medical literature. Heidelberg 1972, pp. 169-171, 367.

- ↑ Wolfgang Ernst : Brain and magic spell. Archaic and medieval psycho-formative healing texts and their natural active components, Frankfurt / M. Bern Bruxelles New York Oxford u. a. 2013, pp. 46–55.

- ↑ Lieberman, Matthew D. et al. (2011) Subjective responses to emotional stimuli during labeling, reappraisal and distraction, in: Emotion 11, 468–488.

- ↑ cf. Friederici, Angela D. , Human language processing and its neural basis, in: Meier, H. u. D. Ploog (ed. :) Man and s. Brain, Munich 1998, pp. 137–156.

- ↑ cf. z. B. for hypnotherapy: Halsband, Ulrike: Neurobiologie der Hypnose, in Revenstorf, Dirk and Peter, Burkhard: Hypnose, Heidelberg 2009, pp. 809f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Ernst : Brain and Magic, Frankfurt / M. u. a. 2013, pp. 131–174.