Parforce hunt

The par force hunt ( French par force , with force) is a hunt in which the hunt pack of dogs is accompanied on horseback. It was already known to the Celts and was particularly popular in the European royal houses in the 17th and 18th centuries. In the period before the Napoleonic wars , the great effort that this type of hunting entails limited it to the nobility . Par force hunting is still practiced today, for example in France, the USA and Australia.

Parforce hunt

During the parforce hunt, an appropriately trained pack of bracken or hounds seeks and follows the tracks of deer , fox , wolves or wild boars . The hunters and the picors , who accompany and guide the pack, ride with them on horses and communicate via trompes de chasse until the dogs cover the game. The parforce horn originally served as a signaling instrument for parforce hunting. The dogs are slower than the game, for example deer, but have superior endurance and thus tire them. The dogs only catch the game and a hunter intercepts it.

The hunt participants follow the pack on horseback. During a par force hunt in the open countryside, the path the hunting party will take is unpredictable. It is determined by the kilometer-long escape route of the game. Large areas are required for par force hunting.

In Germany, in the second half of the 19th century, par force hunts were replaced by drag hunts . With this new form of hunting, a German hunting tradition has developed. On the hunts with packs of dogs, the horns with the fanfare of the "chasse à courre" from France no longer sounded, but mainly parforce horns in Eb. The fanfares of these horns were largely taken over from the Prussian cavalry, to which there was a very close connection. Hunting horn music with the musical style elements of cavalry music in its fanfares and signals today follows on from this tradition of drag hunts with parforce horns tuned in Eb. They also go wonderfully with the small hunting horns and can therefore be heard for the horns tuned in Bb.

Princely parforce hunt in the 17th and 18th centuries

In the late Middle Ages, the wealthy and nobles hunted with horses and dogs. As can be seen on the Duke of Devonshire's 15th century hunting carpet, elegant party hunts were held where jumping was not the primary focus.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, princely par force hunting was carried out at great expense in France, England and Germany. Packs of several hundred dogs were kept.

Hunting castles and aisles

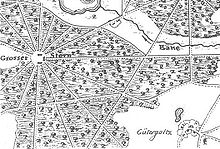

This type of hunting required new hunting facilities, as the riders needed flat and open terrain with many aisles (frames) for the fast ride. Forests were specially prepared for this purpose, such as the Parforceheide in Brandenburg between Berlin and Potsdam with the Stern hunting lodge , which was commissioned by the soldier king Friedrich Wilhelm I and built between 1730 and 1732. A few years earlier, between 1722 and 1724, Landgrave Ernst Ludwig von Hessen-Darmstadt had the Wolfsgarten Castle built in Langen , about 15 kilometers south of Frankfurt am Main . It corresponded to the then common pattern for hunting locks. Because of the high costs, there were only about 10 such parforce hunting equipment in Germany in the 18th century. In addition to the above-mentioned u. a. also at the court of the Mecklenburg dukes in Ludwigslust .

Below the northern Hessian Sababurg , a rondel ( hunting star ) was laid out in the Sababurg zoo in 1779 according to the wishes of Landgrave Friedrich II of Hessen-Kassel . Star-shaped aisles led to it, which can still be recognized today as oak avenues. The southern part of the Rhineland Nature Park , to the west of the large cities of Cologne and Bonn in North Rhine-Westphalia , is crossed by a spider-web-like system of paths that is oriented towards the former Herzogsfreude Castle in Röttgen . In the 18th century, Elector Clemens August von Cologne had these aisles laid out for the purpose of hunting forces.

Environmental damage

The parforce hunt in a princely setting required large and closed terrain. Wild gardens were created, some of which were several thousand hectares in size. Kilometers of ramparts, fences and walls surround the wildlife parks in order to prevent the game from moving to foreign hunting areas and to avoid damage to the fields. A wall around the park of Chambord Castle still exists today . In France, numerous landscape gardeners and foresters took care of the maintenance of the wild gardens.

Large areas of land were required to create the wild gardens, which were ecologically impaired in a relatively short time. Paths and avenues were set up and trees were planted. In the wild gardens, the intensive keeping of large game led to forest damage through game browsing . This was countered in France with the increased cultivation of the beech tree , as it is not bitten. This led to monoculture with negative consequences for the ecosystem. The water supply of the artificially planted wild gardens was difficult. In many cases, water had to be diverted from rivers in order to supply the non-local trees with water and to offer the animals a watering facility.

Large numbers of animals were captured in other areas and taken to the game gardens so that large numbers of animals could be reached there. For this purpose, non-native species also had to be used from areas that were sometimes far away. A lively transport of wild animals developed in Europe. Stocking with non-native species put pressure on the ecosystems.

Parforce hunting in hunting areas outside of the game gardens often caused damage to the fields due to game, as hunting law often did not provide for the regulation of game for the benefit of agriculture.

Criticism of the par force hunt in the Enlightenment

The parforce hunt could often cause great damage to the peasantry, but also to aristocratic landowners, without adequate compensation being granted. In particular, the field damage caused by the game could reach devastating proportions. This is why the topic was repeatedly taken up as a drastic social criticism during the Enlightenment . The poem Der Bauer to his serene tyrant by the poet Gottfried August Bürger (1747–1794) is exemplary:

Who are you, Prince, that

your cartwheel

may roll me up without fear , Your horse may smash?

Who are you, Prince, so that

your friend, your hunting dog, unblown,

may steal and throat in my flesh ?

Who are you that through the seeds and the forest

the hurray of your hunt drives me,

breathe like the game? -

The seed, when your hunt is crushed,

What horse and dog, and you devour,

The bread, you prince, is mine.

You prince did not have egg and plow,

did not sweat through the harvest day.

Mine, mine is diligence and bread! -

Ha! you were the authority of God?

God gives blessings; you rob

You not of God, tyrant!

It remains to be noted, however, that in the 17th and 18th centuries the proper practice of par force hunting was as far as possible while protecting the fruit still on the stalk, i. H. usually only had to be done after the harvest. In most cases, one can assume that hunting was carried out properly, because hunting was practiced as a strictly regulated sport. A large part of the lack of compensation is likely to be due to the inherently difficult evidence and, on the other hand, the high cost burden of the legal proceedings to be conducted, which also prevented less well-off nobles from asserting any claims for damages.

Parforce hunting from the 19th century to the present day

Parforce hunt in Germany

In Germany, even before 1800, parforce hunting was not as widespread as in England or France. Fox hunting requires the largest possible open space, which was rare in wooded Germany. In densely populated Germany there was also a lack of space for deer hunting, which often leads 30 km before the deer can be caught. The hunt for wild boar was easier in this regard. The Napoleonic Wars interrupted the costly princely par force hunt in Germany for a long time. Only a few packs were founded after the Congress of Vienna , and many royal houses did without a pack entirely. The former princely, magnificent hunts developed further and became faster. Since the landscape was now divided by numerous fences and walls, it was necessary to jump. Light, noble riding horses with great jumping ability were bred, for example the light loft of the Trakehner , into which a lot of English thoroughbred was crossed.

Packs

The royal Hanover pack , which consisted of 400 dogs, was almost completely lost by the French occupation in 1806. It was re-established with Harriern after the Congress of Vienna in 1815 . It belonged to the English royal family until 1866. The successor was the Foxhound pack of the Hanover Military Riding Institute , which existed from 1866 to 1914.

At the Prussian court there was a foxhound pack from 1827 to 1914 , with kennels in Grunewald. Box hunts for wild boar. In 1914, 30 paddocks hunted (this corresponds to 60 dogs ready for action, a total of probably around 75 dogs), which came to an end in the First World War .

In Bohemia, which belonged to Austria-Hungary , Count Kinsky founded the Pardubice deer pack at Karlskron Castle around 1830 . Kinsky was the master of the pack of 40 paddocks foxhounds. He bred the Kinsky horse , a new breed of hunting horse .

In the law on the basic rights of the German people of 1848 , paragraph 37, the privilege of sovereigns and the high nobility to hunt on foreign land is abolished. Although the law was often disregarded, it restricted par force hunting with its unpredictable route.

Box hunting

Not until the middle of the 19th century did the number of packs increase again, especially in Mecklenburg, Western Pomerania, Brandenburg and Prussia. Especially after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871 , par force hunting took off again in Germany. On the one hand various pack dogs came from France to Germany, on the other hand Germany was united and the 2nd German Empire was founded. This upswing lasted until the First World War. However, it was predominantly smaller, purpose-oriented, sporty packs that were run by the landed gentry and the military and did not serve for representation. Later, the bourgeoisie, strengthened by the industrial revolution , came along, but because of their urban roots, they often preferred to hunt on foot.

These hunts often until several were dragging down before then box game was suspended, that should then cover the dogs in a final run. Box game was game that was transported in a box. It was either raised in a wildlife park or captured in advance. The box game had little chance of escaping the dogs due to a lack of experience and the often small head start that was granted to them. Wild boar could sometimes be caught by the dogs just one kilometer after being abandoned. Deer had a better chance of escaping the hunters. Box hunts were already criticized at the time as being unhealthy . The dragging of the box hunts, in contrast to the game hunts, could be planned so that only a small part of the hunting route was unpredictable. The disadvantage was the laborious and expensive rearing of box game. In the military in particular, the focus was on training, and so a plannable hunting route was preferred, which could be designed with high obstacles, walls and wide trenches. The hunting races developed from this tradition .

During the First World War , most of the packs were broken up and only a few, mostly half-starved dogs survived the war. Many dogs ended up in France and England. Many packs were formed between the wars, but box hunts are no longer successful because of the high costs. Instead, mainly drag hunts were ridden. For these reasons, the German par force hunt cannot be compared with the great tradition in England or France. Many hunting customs and pack dog breeds come from France and England.

termination

In Germany , under National Socialism , the par force hunt for live game was banned by Hermann Göring by the regulation supplementing the Reichsjagdgesetz of July 29, 1936 ; the Reich hunting law was dated July 3, 1934. In 1939, after the annexation, the ban was extended to Austria. Bernd E. Ergert , Director of the German Hunting and Fishing Museum in Munich, said of the ban: "The nobles were very angry, but they couldn't do anything about it because of the totalitarian regime."

The Second World War also ended hunting riding . A few pack dogs survived and were taken over by the British and French occupation forces after the war. During the occupation , the British rode par force hunts in the Lüneburg Heath, in the area of Osnabrück and ran a pack of Bloodhounds in the Senne. The French hunted in Württemberg from 1949 to 1952 (Rallye Wurtemberg with 25 paddocks Angelo-Poitevins for deer, kennels near Tübingen). The Federal Hunting Act, which came into force in 1953, forbade par force hunting with every hunt.

Riding and drag hunts are a sporting event and not a hunt in the true sense of the word. You experience a fast long ride in a large group with or without packs of dogs on a prepared route with obstacles. Spectators are led to the most beautiful places where you can see the hunting route with jumps. The game replaces a rider who often carries a foxtail as prey .

Fox hunting in Great Britain

The parforce hunt for the fox had a long and unbroken tradition in Great Britain until it was banned in 2005, which was only briefly affected by the two world wars.

In addition to animal welfare issues , the dispute about a ban on fox hunting always had a socio-political background, as many jobs were connected with fox hunting. Traditionally, farmers consider fox hunts useful because they hope it will contain the foxes that threaten their lambs. Even today, drag hunting, which replaced fox hunting, is of great social importance.

Attempts to outlaw parforce fox hunting in the UK have sparked heated debate and scientific research. In Great Britain, for example, it was only allowed in certain areas and under certain conditions at times.

On September 15, 2004, a majority in the House of Commons voted in favor of a complete ban on horse fox hunting ( Hunting Act 2004 ). The Burns Inquiry was preceded by an investigation into the extent to which hunting complies with animal welfare regulations. It dealt not only with the hunt for foxes, but also with the hare-baiting . Despite several demonstrations (e.g. Countryside Alliance March in London) in which large parts of the rural population spoke out against a ban, a law was passed on November 18, 2004 by the House of Commons through the use of a Parliament Act to prevent dog hunting banned from February 18, 2005 in England and Wales. Traditional fox hunting remained legal in Northern Ireland .

MacDonald (1993) examined 81 hunting grounds in England in the 1970s / 1980s and wrote: “In a seven month season, a pack of foxhounds hunted an average of 2.5 days a week. A hunt has an average of 120 paying, mounted members, and 50 riders and 20 to 100 cars can follow the hunt on a hunting day. The pack hunt on farm land (around a third of the farmers are actively involved, while 2.2 percent do not like to see the dogs on their land or even block it for hunting). (...) Traditional packs can include a 'construction victim' who closes the surrounding foxholes at dawn so that the foxes cannot spend the day underground. The around 40 dogs now browse the area and 'push the fox out' (they scare him off). One to four foxes are kicked out on an average day, and some of them are then hunted. The chase generally lasts less than an hour. ”Sometimes the pack alternates from one fox to another, or a fox is hunted several times in a row. "About half of the foxes captured are killed by dogs, the other half are shot after terriers have 'blown' them out of the burrow."

Since par force hunting was banned, the number of drag hunts in England has increased.

Parforce hunt in France

In France, the conditions for par force hunting were better than in Germany. It is less densely populated and offers more space for parforce hunt for wild boar, roe deer and red deer, which have a good chance of escaping. The French Revolution marked a turning point in hunting, but the packs soon recovered. Neither 1870/71 nor the two world wars brought hunting riding to a standstill, so that a great hunting tradition could develop in France as well. In France, depending on local traditions and circumstances, both drag hunts and parforce hunts, which are called chasse à courre in French , are carried out.

See also

literature

- Caroline Blackwood: Tally-Ho. About the English fox hunt , Rio Verlag, Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-9520059-2-4

- Contributions by A. Corvol, J Buridant and I. Trivisani-Moreau in XVIIe Siècle No. 226, 57th year 2005, pp. 3–40

- Wilhelm König: Die Schleppjagd , Olms-Verlag, Hildesheim, Zurich, New York, 1999, ISBN 3-487-08407-4

- Hanns Friedrich von Fleming: The perfect German hunter . JC Martini, Leipzig 1749, Von dem Par-Forçe hunting, p. 294 ff . ( Digitized online ).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Allgemeine Forst- und Jagd-Zeitung, No. 45, June 4, 1825, Volume 1, Verlag JD Sauerländer Description of the hunt of Duke Carl Eugen von Württemberg. P. 217 ff in the PDF document

- ↑ Tamsin Pickeral, Das Pferd , 2007, Cologne, p. 172, ISBN 978-3-8321-7794-2

- ↑ a b c Wilhelm König, Die Schleppjagd , 1999, Olms, Hildesheim, Zurich, New York, pp. 65, 66 and 67

- ↑ Basic rights 1848

- ^ Wilhelm König, Die Schleppjagd , 1999, Olms, Hildesheim, Zurich, New York, pp. 1, 12f.

- ^ RGBl., 1936, I, p. 578 at ALEX Historical legal and legal texts online - an offer from the Austrian National Library

- ^ RGBl., 1934, I, p. 549 at ALEX Historical legal and legal texts online - an offer from the Austrian National Library

- ↑ Thanks to Hitler, hunting with hounds is quietly forbidden , The Telegraph. September 22, 2002. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- ↑ Wilhelm König: The drag hunt. 1999, p. 16 f. and 91.

- ↑ so-called Objective prohibition in accordance with Section 19 Paragraph 1 Number 13 of the Federal Hunting Act

- ↑ D. MacDonald: Among Foxes - A Behavioral Study. Knesebeck-Verlag, Munich 1993, 253 pp.

- ^ All about drag hunting , Horse & Hound . January 7, 2005. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ^ Website of the English The Masters of Draghounds and Bloodhounds Association . Retrieved January 20, 2012.