Oberkassel double grave

The double grave of Oberkassel was discovered in 1914 by quarry workers in what is now the Oberkassel district of Bonn . The skeletons of a 50-year-old man, a 20- to 25-year-old woman, the remains of a dog, other animal remains and processed animal bones lay under flat basalt blocks and wrapped in a sparse layer of clay colored by red chalk .

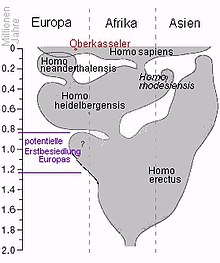

The well-preserved skeletons from the time of the late Ice Age penknife groups are between 13,300 and 14,000 years old according to various 14 C dates . This makes it - after the grave in the Klausenhöhle in Bavaria - the second oldest burial of anatomically modern humans ( Homo sapiens ) in Germany. The skeletons, the grave goods and part of the dog's teeth can be seen in the LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn . On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the find, the museum showed the exhibition Ice Age Hunters - Life in Paradise from October 23, 2014 to June 28, 2015 . For this exhibition, the faces of the two buried people were reconstructed.

Find

In February 1914, two workers discovered bones while clearing rubble in the “Am Stingenberg” quarry , which they recognized as human remains. The bones and the surrounding earth were discolored reddish. The bones were in good condition, two skulls almost intact. The work was interrupted and the Oberkassel teacher Franz Kissel made sure that the find was saved. Under one of the skulls a narrow bone object about 20 cm long was discovered, which was carved at one end. The bones were deposited in an old ammunition box that had contained explosives for the rock blasting.

The quarry owner Peter Uhrmacher reported the find to Bonn University . On February 21, the physiologist Max Verworn , the anatomist Robert Bonnet and the geographer Franz Heiderich appeared in Oberkassel. Since the notification had mentioned a "hair arrow", a female hair ornament, the scientists initially believed in a find from Roman or Frankish times. However, they recognized the hair arrow as a bone tool, as it had been used as a straightener or scraper for fur at the end of the Ice Age (“Diluvium”) .

Location

In the “Am Stingenberg” quarry in Oberkassel, basalt had been quarried for decades. It rose around 25 million years ago along a fissure parallel to the course of the Rhine and which is part of the tertiary volcanism of the Siebengebirge . This basalt train, the " Rabenlay ", determined the direction of the Rhine. At this southern point it bears the name "Kuckstein".

Before the quarry was built, there was a precipice here, which was removed by the quarry. The site was at the foot of the precipice at a height of 99 meters above sea level . A mapping of the locality did not take place, but the Bonner geologist Gustav Steinmann written a description of the location. The top layer was about 0.5 m thick and consisted of overburden from the quarry and a humus cover. Underneath there was about 6 m thick hanging debris made of more or less weathered blocks and chunks of basalt mixed with basalt clay. There was no loess material in or above it, but rubble made of quartz that had been rolled or washed from the main terrace from the level of the cuckoo.

At the base of this hanger debris store were the skeletons and additions, as well as a canine tooth of an animal, which Steinmann assumed was a reindeer , and a "bovid tooth". Both teeth were in a reddish layer on and in 0.1 m of sandy loam. Below that, up to 4 m deep, was gray-yellow sand of the high terrace of the Rhine. It was to be found in the same geological position at several points in the area. Underneath there was 1 m of existing basalt, which continued in the depths and was clayey decomposed on the surface. In the red-colored culture layer, which continued towards the basalt wall, animal bones were also found, which Steinmann described as follows: "[...] a right lower jaw from a wolf , a tooth from a cave bear and bones from the deer , as well as charcoal that adhered to some bones."

Experts do not rule out the possibility of finding more skeletons under the hanging debris store.

Find report

In 1919, Verworn, Bonnet and Steinmann published a comprehensive report on the find in Oberkassel, which the University of Bonn published on the occasion of its centenary. Verworn writes about the circumstances of the find:

“With impatience we followed Mr. Uhrmacher to the work hut of the large basalt quarry, where the bone finds were presented to us in an old explosives box. We immediately saw two well-preserved skulls, only one of which was slightly injured by a hack while excavating. What we first noticed about one skull was the extraordinarily strong development of the muscle attachment points. [...] Above all, however, we noticed that not only the skulls, but also a large part of the other skeletal bones, which were jumbled up in the small box, covered in a sometimes quite thick layer of red color material, as we can see from the Paleolithic sites of the Vézèretales, something very familiar, appeared covered up, and that this pigment, which apparently consisted of red chalk, had undoubtedly partially impregnated the skeletons in the earth , and was therefore at least of the same age as them. In the meantime, we still hardly dared to believe in a Paleolithic age of the skeletons until we had visited the site ourselves. In the pouring rain, Mr. Uhrmacher jun. to the place where the skeletons were revealed. "

Two days later, further excavations were carried out, with the Bonn scientists wanting to check whether the find layer had a further expansion in area and depth and whether other finds were to be expected in the vicinity. It quickly became apparent that almost the entire extent of the site had already been uncovered and that it could only extend a little further in the direction of the gravel wall. This assumption was correct, the site could be traced about half a meter into the gravel dump. Some tarsal bones and toe phalanx were found. But then the red chalk layer stopped and there was nothing left of bone fragments. Also in the neighborhood, as far as it was accessible for a test excavation, there were no more signs of further finds, apart from a few scattered bone fragments that had been lost when the skeletons were first recovered.

Storage or burial place?

On June 23, 1914, Verworn, Bonnet and Steinmann reported on the finds to the Bonn Anthropological Society and answered the question of what kind of place it was where the skeletons had been found. They came to the conclusion that the find was a burial place and not a storage place. Presumably the diluvial hunters would have had their camp nearby, probably under the protection of the basalt wall, and buried the dead with their additions not too far away, carefully surrounding them with copious amounts of red paint according to the usual ritual and with large stones covered.

What can no longer be precisely reconstructed due to the circumstances of the find is the location of the two skeletons in the grave. It is questionable whether they were buried next to each other as they are today in the LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn. The lack of knowledge about this is also one reason why the circumstances of their death and the reasons for the joint burial are still unclear to this day.

skull

In 1914, Robert Bonnet published an initial description of the two skeletons in the journal Die Naturwissenschaften , which was further specified five years later in a publication from Bonn University. Bonnet's skeletal analysis is today praised by archaeologists and anthropologists as extremely precise and complete, which leaves nothing to be desired.

In addition to the well-preserved skulls with lower jaws, Bonnet found that almost all the important bones from the male and female skeletons had either been recovered in whole or in part. According to this finding, only the wrist and tarsal bones, a femur, a few fingers and toes, and the sternum were missing.

From this the scientist concluded that the Oberkassel find was one of the best diluvial finds up to this point due to its state of preservation, due to the certainty of determining its geological and archaeological age, due to its completeness and the fact that it consists of a male and female skeleton .

Woman's skull

The woman's skull had been loosened in the very simple sutures and disintegrated into its individual bones, but apart from parts of both temporal scales , the nasal bones and a few defects at the base of the skull , it could be reassembled.

The long-headed skull has a greatest length of 184 mm, a greatest width of 129 mm and a greatest height of 135 mm (measured from the anterior edge of the occipital opening to the apex). Its horizontal circumference is 512 mm. In side view, the contour of the brain skull runs over the well-curved, steep forehead to the occipital opening in a round arc. When viewed from the front, the face shows a strongly developed jaw apparatus . The moderately broad forehead is divided by a forehead seam . The square eye sockets are relatively large. The nostril is of moderate size, the palate is deeply arched, a very strong lower jaw with a clear chin completes the steep profile line. The dentition was complete except for the third right upper molar during life. The last three molars are less worn than the rest of the teeth, so they haven't erupted for too long.

These values and those of the other skeletal bones allowed Bonnet to conclude “a graceful body about 155 cm long”. Today's calculations of the body length of women range between 160 cm ± 3.7 cm and 163 cm ± 4.1 cm. As for the woman's age, Bonnet assumed she was around 20 years old. Today their age is more likely to be around 25 years.

Men's skull

In contrast to the skull of the woman, for Bonnet the skull of the man shows a "gross disproportion" to the moderately broad and slightly inclined forehead and the well-arched skull due to its width and low profile . He estimated the man's age to be 40 to 50 years.

The greatest length of the skull is 193 mm, the greatest width 144 mm, the greatest height 138 mm, the horizontal circumference 538 mm. The capacity was determined to be approx. 1500 cm³. The low, rectangular eye sockets are strongly inclined outwards and downwards, above them a uniform, about 8 mm wide, upper eye bulge is noticeable. A lower middle forehead bulge extends and flattens out to the apex. The nostril is narrow in relation to the width of the face, the palate, apart from the partial regression of the tooth socket process in relation to the rest of the jaw structure, remarkably small.

In the upper jaw, only the last two molars on both sides and the left canine were left. Incisors in the lower jaw fell out during life, and one incisor and one canine subsequently fell out. All dental crowns are, as is often found on the bites of the quaternary skulls of young, worn down except for small remnants of the tooth enamel . The exposed dentin is black.

From these values and the strong development of all muscle processes on the skull and on the extremity bones, Bonnet drew the conclusion that the man from Oberkassel had an "unusual" physical strength and was about 160 cm tall. Today's calculations of body length range between 167 cm ± 3.3 cm and 168 cm ± 4.8 cm.

meaning

In his report, Robert Bonnet attempted to classify the finds with regard to the affiliation of the Oberkassel people to previously known populations . For him, some of the findings he found in the man indicated that he was close to the Neanderthals . Others, such as the wide lower face with the lower rectangular eye sockets, the narrow nose and the V-shaped lower jaw with his pronounced chin triangle made him of the characteristics of Homo sapiens counting Cro-Magnons close. For the Bonn scientist, the two skulls showed not only unmistakable similarities but also not inconsiderable differences from one another. "In both skulls," says Bonnet, "the very remarkable consequences of crossings that took place during the Diluvian are expressed."

After his first attempts at classification in 1914, he had the plan to compare the Oberkassel skeletons with other Pleistocene skeletons in order to substantiate and refine his results. Because of the First World War , however, he had to limit himself to literature data, and access to other European museums and collections was not possible for him. After the First World War, he didn't have much time to research any further. Bonnet died in 1921.

The first to classify the Oberkassel skeletons as typical representatives of the Cro-Magnon type was Josef Szombathy in 1920. Seven years later, Karl Saller took up the question and assigned the finds to an "Oberkasselrace". In doing so, he gave them an autonomy that was not and is not shared by other scientists. Today there is agreement that “the Upper Palaeolithic were decidedly more homogeneous than the ideal typological differentiations into a Cro-Magnon, Grimaldi, Brünn or Combe-Capelle breed suggest”.

The Mainz anthropologist Winfried Henke , for whom the Oberkassel finds are the "most significant Upper Palaeolithic fossils of the Federal Republic of Germany" , subjected the skeletons to a scientific inventory in 1986 . In addition, he examined again, now with the help of modern research methods, in particular the two skulls. His aim was to determine the " morphological affinities" to comparable European finds and to answer the question whether the Oberkassel can be clearly differentiated craniologically from other European fossil finds from the same time or contemporary periods , or whether based on "comparative-static findings it can be assumed that the Oberkasselers fit into the comparative sample without being noticed ”.

Henke came to the conclusion that the man from Oberkassel deviates from the comparison sample in particular "in the width dimensions of the facial skull ( zygomatic arch width , lower jaw angle width , orbital width ) and the occipital width dimensions" , "while the other metric data of the cranium largely correspond to the average and are therefore inconspicuous are " . The woman from Oberkassel shows a clear deviation from the narrower dimensions of the brain skull compared to her gender-specific comparison sample. "Overall," says Henke, "the female skeleton deviates significantly from the type pole opposite to the male skull due to the univariate metric analysis."

In summary, Henke's analysis confirmed "that the Oberkasselers occupy an extreme position in some metric features" . With regard to their morphology, the examined skulls were by no means “outside the distribution spectrum of the comparison samples” . The man from Oberkassel can only be characterized as “average robust male” based on the metric data of the skull , while Henke classified the woman “as graceful and clearly tending towards the hyperfeminine type pole” .

With regard to the classification of the man from Oberkassel, he assigns himself, according to Henke's study, “clearly to the Cromagniden circle of forms” . In the woman von Oberkassel, in contrast to the man, Henke sees clear affinities to the Combe-Capelle type, to a population in which “a pronounced gracefulness is emerging” and the Henke viewed as complementary to the Cromagnid type. (Note: As only became known in 2011, the burial of Combe Capelle can be classified in the Mesolithic , so it represents a potential descendant of Frau von Oberkassel.) Whether these external similarities also indicate family relationships can only be determined through further molecular genetic and archaeometric research.

In such research there is also “a great chance” of proof, according to Henke, that “the Oberkasselers played a decisive role in our direct ancestry” .

Grave goods

In addition to the human remains of the Oberkassel grave, the processed grave goods are of particular archaeological value because they are important evidence of the cultural level in which the people lived. It was they who in 1914 provided clues for the alleged assignment of the grave find to the lower Magdalenian .

Quarry workers discovered the “hair arrow” as soon as they were rescuing the skeletons. Heiderich found the find, which scientists initially called “animal head” or “horse head”, when he began sorting the parts found in the quarry. He noticed small pieces of bone with engraved lines that did not belong to the two human skeletons. Verworn reports:

“When he [Peter Uhrmacher] brought these fragments to me that evening, we were pleased to find that they belonged together and that they came from a flat, plastically carved animal head, as has become known several times from sites in the south of France. The fractures of the pieces were still fresh and sharp, so that there was no doubt that the carving had not been broken by the workers until the skeletons were found. On the other hand, it was clear from the fact that the workers had removed these bone fragments from the ground at the same time as the skeletal bones, as well as from the red chalk coating on them, that the animal head carving represented an addition of the skeletons, as well as the 'hair arrow' as an addition of the skeletons had been found. For the complete composition of the animal head carving, a larger fragment was missing, which must have been lost when the bone remains were removed from the ground and could not be found when the site was subsequently searched. "

Verworn saw a grave object in another animal bone. He described it as an "awl-shaped animal bone".

"Hair arrow"

The “hair arrow” is a very finely polished object carved out of hard bones, approx. 20 cm long, with a rectangular cross-section, which Verworn called a “smoothing instrument”. At the end of the handle there is a small animal head that is similar to a rodent's head or a marten 's head. The other end is blunt. On the narrow sides the instrument shows a notch cut decoration which is very characteristic of the reindeer age .

The reason why the bone stick was referred to as a "hair arrow" in the first reports on the discovery was probably due to the fact that it was located under the skull of one of the two skeletons and therefore suggested that it was a female hair ornament . In later descriptions it was referred to as a "scraper" , "smoother" or " bone slab " . Since this find has remained without parallels to this day, no precise statements can be made about its actual use.

"Horse head"

Even more important than the “hair arrow” is the second grave gift with regard to the chronological assignment of the grave, because there were parallels to this as early as 1914. “This 'bone carving'” , Verworn wrote, “is one of those small, board-like, narrow horse heads engraved on both sides, as found in large numbers and in many variations by Girod and Massenad in Laugerie Basse and by Piette in the Pyrenees , and a characteristic one Present the key fossil of the lower Magdalenian strata. ” In 1914, Max Verworn saw one of those horse heads from these strata in the assembled figure, which was around 8.5 cm long, 3.5–4 cm wide and almost 1 cm thick.

Since the 1920s, carving has generally been seen as depicting an animal's body, today the depiction of an animal belonging to the deer family. A complete picture of the find cannot be created. He lacks the head, the rear quarter of the body and the legs. The outline of the carcass is cut out while the inside surface is engraved. The engravings on the inner surface consist of parallel lines. The shape of the body is emphasized by clear parallel hatching on the abdomen and neck.

Grave goods in the layers of the middle Magdalenian in south-western Europe, in France and Spain are called contours découpés (literally translated: "cut out outlines"). They are usually animal heads, often horse heads, that have been found in heaps in southwest France. For a long time, with the help of the small carving, the entire Oberkassel find was classified in Magdalenian IV using this supposed parallel.

In addition to the radiocarbon dating , which in fact excludes an assignment to Magdalenian IV, the assignment of the Cervid sculpture cannot be kept stylistically. The Oberkassel piece is not a contour découpé in the narrower sense, as these were almost without exception made from the tongue bones of horses, in contrast to the object by Oberkassel. In addition, it was found very far away from the rest of the distribution area.

This view is supported by the fact that comparable objects have meanwhile been found by the penknife groups . In particular, the amber moose from Weitsche (Lower Saxony) is used as a very plausible parallel. Weitsche is depicted as a cow elk , with almost identical decorations. Researchers at the University of Bonn assume today that this addition to the Oberkassel grave is also a representation of a moose.

An "unprocessed awl-shaped animal bone"

Investigations have shown that Verworn's assessment is correct and that a third find is to be regarded as grave goods. He called the find an "unprocessed awl-shaped animal bone" . The piece is the penis bone of a bear, probably a brown bear. However, and in contrast to Verworn's knowledge of 1919, it has "a series of fine cut marks that were subsequently superimposed by hematite ". As with the “hair arrow” and the second bone carving, these workings on the find suggest that he was an early human cultural asset.

The dog and other remains of the fauna

In comparison to the skeletons and the cultural additions, the scientists who evaluated the Oberkassel find after the discovery of the grave paid little attention to the animal bone remains found. In the first report from 1914 they were only mentioned in passing, Steinmann went into more detail in 1919 on this part of the grave finds in his text "The geological age of the finds" .

In 1986 Günter Nobis published the animal bones again. The findings that Steinmann published in 1919 were partially revised. In the meantime, only the brown bear ( Ursus arctos ) and domestic dog ( Canis familiaris ) are described as predators, in the other bones the cloven-hoofed red deer ( Cervus elaphus ) and aurochs ( Bos primigenius ) / steppe bison ( Bison priscus ). The exact determination of the bovine bones is not possible on the basis of the remains. Nobis mistakenly identified lynx ( Lynx lynx ) and roe deer ( Capreolus capreolus ), but from today's perspective these bones can also be assigned to the domestic dog. The fauna suggests light forest cover, as is typical for the late glacial interstadials - especially the Alleröd interstadials . The allocation to the Alleröd Interstadial is also obvious because of the archaeological classification in the time of the Federmesser groups, but would only coincide with the more recent radiometric data.

“Of particular importance,” said Nobis in the summary of the results of his research, “are the remains of canids in the animal material from Oberkassel that were previously ascribed to the wolf. The morphological and metric comparison teaches that the sum of domestication characteristics speaks for a domestic dog. With due caution, one can speak of a late Paleolithic pet becoming the wolf: The Oberkassel domestic dog, which accompanied the hunting people of the Cromagnon breed about 14,000 years ago , is thus the oldest domestic animal known to man. "

The appearance of the domestic dog in Oberkassel and the almost simultaneous appearance of the first domestic dogs in Central Europe, the Middle East, the Far East and North America "suggests several independent centers of autochthonous wolf domestications in the Upper Paleolithic" A 2013 published study of the mtDNA of 18 prehistoric canids from Eurasia and America, on the other hand, allows the conclusion that the origin of the domestication of the wolf is to be found in Pleistocene Europe, in a time window between 32,000 and 18,000 years ago. The dog from Oberkassel was one of the specimens examined.

Previous age determination and new research

In the years and decades after 1914, in addition to the age determinations that result from the geological conditions of the site, scientists had the opportunity to make a historical classification by comparing the skeletons and the cultural additions of the grave with other archaeological finds. Radiocarbon dating has also been around since the 1960s . Bone samples from the Oberkassel double grave were subjected to this procedure in 1994 as part of a study at Oxford University . The dating was 12,200 - 11,500 uncal. BP , which corresponds to about 12,000 - 11,350 BC when calibrated . A study by the Rheinisches Amt für Bodendenkmalpflege in 1994 yielded similar results . Employees took soil samples from the soil layer in which the grave was located at a point about 80 m from the site. Martin Street, a prehistorian of the RGZM , summarized the results of the investigations in 1999 in articles on the chronology of archaeological sites of the last glacial in the northern Rhineland . After that, the two Oberkassel people lived in the phase of the latest Magdalenian or the time of the penknife groups .

On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the discovery of the site in 2014, the grave complex has been completely re- examined as part of a research project by the LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn since 2009. Under the direction of the prehistorian Ralf W. Schmitz from the LVR-Landesmuseum , 30 international scientists from various disciplines worked on the investigations. The following analyzes were planned at the grave complex: determination of the exact age of the finds, examination of the human skeletons for injuries, diseases, deficiency symptoms, nutrition, migration movements and DNA as well as facial reconstructions, DNA analyzes on dogs to clarify the domestication question and stylistic classification and material determination of the art objects. In addition, the LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn planned a special exhibition with a focus on Ice Age art in the anniversary year. An accompanying symposium and the publication of all results in an anthology were also planned.

The first results of more recent studies were published in early 2013. On the question of the relationship between the two people from Oberkassel, an employee of a study by an international team of researchers led by Johannes Krause from the University of Tübingen , which is the DNA of the oldest skeletal finds from Germany and Europe - e.g. B. the human remains of a triple burial in the Czech town of Dolní Věstonice - examined: "We now know that the two were not as closely related as siblings are." The Oberkasselers played a role in this study in connection with the central question of when the first human (Homo sapiens) left Africa for Europe. Result: this event must have occurred 62,000 to 95,000 years ago today.

Lost and found and exhibition

The skeletons and other finds from the Oberkassel grave are now in the LVR State Museum in Bonn. In the exhibition Roots - Roots of Mankind from July 8th - November 19th 2006 they were next to the remains of the " Neanderthal child from Engis " (Belgium), next to skeletal remains of the earliest anatomically modern humans from Europe (" Oasis 1 and 2 "from Romania ) and many other original finds.

Reconstructions

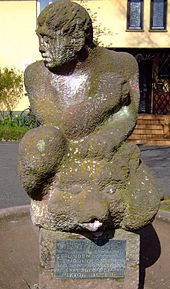

Since the find, artists and scientists have repeatedly made a picture of the dead buried in the Oberkassel grave and created graphic or plastic images.

Not far from the site in Oberkassel there is a monument by Viktor Eichler: The first Rhenish Stone Age man . The so-called "Homo obercasseliensis" by Eichler following research approaches from the 1920s and 1930s crouches over a killed bear. "Homo obercasseliensis" and prey are on a pedestal in the middle of a well. An inscription indicates the age of the "first Rhenish Stone Age man" at 40,000 years.

As a demo of a woman from the end of the last Ice Age, a female figure was created by Elisabeth Daynès for the Neanderthal Museum , representing an attempt to reconstruct the woman from the grave in Oberkassel.

In 1964, Mikhail Gerasimov (1908–1970) published a work in which he gave a face to fossil skulls. It also contains reconstructions of the heads of the two dead from the Oberkassel grave.

Location today

Since 1989 there has been “Am Stingenberg” in Oberkassel, a little below the actual site of the find at the disused quarry on the Rabenlay, a place to commemorate the find from 1914. A plaque that the local history association has put up informs visitors and passers-by about the two dead and the grave goods.

In memory of Franz Kissel, who made sure that the skeletons and grave goods were secured after the grave was found, a street in Oberkassel is now called Franz-Kissel-Weg.

literature

- Michael Baales : Excursus: Bonn-Oberkassel (North Rhine-Westphalia). In: The late Paleolithic site of Kettich. Publisher of the Roman-Germanic Museum, Mainz 2002.

- Anne Bauer: The Stone Age People of Oberkassel - A report on the double grave on the Stingenberg . (= Series of publications by the Heimatverein Bonn-Oberkassel eV No. 17). 2nd edition, 2004.

- Winfried Henke, Ralf W. Schmitz, Martin Street: The late Ice Age finds from Bonn-Oberkassel. In: Rheinisches Landesmuseum: Roots - the roots of mankind. 2006.

- Ralf-W. Schmitz, Jürgen Thissen: Follow-up examinations in the area of the Magdalenian discovery site in Bonn-Oberkassel. In: Archeology in Germany. No. 1/47, 1995.

- Ralf-W. Schmitz, Jürgen Thissen, Birgit Wüller: Discovered 80 years ago. New investigations into finds, findings, geology and topography of the Magdalenian discovery site in Bonn-Oberkassel. In: Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn. No. 4, Bonn 1994.

- Martin Street: A reunion with the dog from Bonn-Oberkassel (PDF; 4 MB). In: Bonn zoological contributions. No. 50 (2002), pp. 269-290.

- Martin Street, Michael Baales, Olaf Jöris: Contributions to the chronology of archaeological sites of the last glacial in the northern Rhineland. In: R. Becker-Haumann, M. Frechen (Ed.): Terrestrial Quaternary Geology . Cologne 1999.

- Birgit Wüller: The full-body burials of the Magdalenian. (= University research on prehistoric archeology. No. 57). Bonn 1999.

- Ralf W. Schmitz, Susanne C. Feine, Liane Giemsch: Young woman and old man with a dog. The extraordinary double grave of Bonn-Oberkassel. In: Michael Baales, Thomas Terberger (Hrsg.): Welt im Wandel. Life at the end of the last ice age , special issue 10/2016 of the journal Archeology in Germany , pp. 67–77.

Web links

- Current events on the Oberkassel people in the anniversary year 2014

- Research project to re-examine the Oberkassel grave complex

- The Oberkassel Stone Age man, page of the Uhrmacher family (quarry owners) about the grave ( Memento from April 8, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- The Stone Age people of Oberkassel and the domestic animal, the dog - evolution of the Stone Age

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b M. Verworn, R. Bonnet, G. Steinmann: The diluvial human find from Obercassel near Bonn. In: The natural sciences. No. 27, 1914, pp. 649/650.

- ↑ Monument and History Association Bonn-Rechtsrheinisch : Circular 03/2012 ( Memento from February 22, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 145 kB)

- ↑ M. Verworn, R. Bonnet, G. Steinmann: The diluvial human find of Obercassel near Bonn. In: The natural sciences. No. 27, 1914, p. 647.

- ^ W. Henke, RW Schmitz, M. Street: The late Ice Age finds from Bonn-Oberkassel. In: Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn: Roots - roots of humanity . Bonn 2006, p. 244.

- ↑ RWS (= Ralf-W. Schmitz): Homo sapiens from Bonn-Oberkassel (Germany). In: Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn: Roots - roots of humanity . 2006, p. 350.

- ↑ M. Verworn, R. Bonnet, G. Steinmann: The diluvial human find of Obercassel near Bonn. In: The natural sciences. No. 27, 1914, pp. 648/649.

- ^ A b W. Henke: The morphological affinities of the Magdalenian human finds from Oberkassel. P. 331.

- ^ W. Henke: The morphological affinities of the Magdalenian human finds from Oberkassel. P. 361.

- ↑ Almut Hoffmann u. a .: The Homo aurignaciensis hauseri from Combe-Capelle - A Mesolithic burial. In: Journal of Human Evolution. 61 (2), 2011, pp. 211-214. doi: 10.1016 / j.jhevol.2011.03.001

- ^ W. Henke, RW Schmitz, M. Street: The late Ice Age finds from Bonn-Oberkassel. In: Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn: Roots - roots of humanity . 2006, p. 248.

- ↑ a b M. Verworn, R. Bonnet, G. Steinmann: The diluvial human find from Obercassel near Bonn. In: The natural sciences. No. 27, 1914, p. 646.

- ↑ A. Bauer: Die Steinzeitmenschen von Oberkassel - A report on the double grave on the Stingenberg. P. 39.

- ↑ Birgit Wüller: The whole body burials of the Magdalenian. In: University research on prehistoric archeology. No. 57, Bonn 1999.

- ^ M. Baales: Excursus: Bonn-Oberkassel (North Rhine-Westphalia). In: The late Paleolithic site of Kettich. Publisher of the Roman-Germanic Museum, Mainz 2002.

- ^ Stephan Veil, Klaus Breest: The archaeological context of the art objects from the Federmesser site of Weitsche, Ldkr. Lüchow-Dannenberg, Lower Saxony (Germany) - a preliminary report. In: Berit Valentin Eriksen, Bodil Bratlund: Recent Studies in the Final Palaeolithic of the European Plain. Aarhus University, 2002, pp. 129-138.

- ^ According to Liane Giemsch, project manager of the “Research project to re-examine the late Paleolithic double burial of Bonn-Oberkassel” at an event on February 13, 2014.

- ^ W. Henke, RW Schmitz, M. Street: The late Ice Age finds from Bonn-Oberkassel. In: Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn: Roots - roots of humanity . 2006, p. 251.

- ↑ Günter Nobis: The wild mammals in the human environment of Oberkassel near Bonn and the domestication problem of wolves in the Upper Palaeolithic. In: Bonner Jahrbücher. 186, 1986, pp. 368-276.

- ↑ a b Winfried Henke, Ralf W. Schmitz, Martin Street: The dog from Bonn-Oberkassel and the other remains of the fauna. from: The late Ice Age finds from Bonn-Oberkassel. In: Rheinisches Landesmuseum: Roots - the roots of mankind. 2006, pp. 249-252.

- ↑ Günter Nobis: The wild mammals in the human environment of Oberkassel near Bonn and the domestication problem of wolves in the Upper Palaeolithic. P. 375.

- ↑ O. Thalmann, B. Shapiro et al. a .: Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Ancient Canids Suggest a European Origin of Domestic Dogs. In: Science. 342, 2013, pp. 871-874, doi: 10.1126 / science.1243650 .

- ↑ M. Baales, M. Street: Late Palaeolithic Backed Point assemblages in the northern Rhineland: current research and changing views. In: Notae Praehistoricae. 18, 1998, pp. 77-92.

- ↑ Ulrike Strauch: Scientific investigation of grave finds in Oberkassel.

- ↑ RW Schmitz, L. Giemsch: Neandertal and Bonn-Oberkassel - new research on the early human history of the Rhineland. In: Fundgeschichten - Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia: Book accompanying the state exhibition in North Rhine-Westphalia 2010 (= writings on the preservation of monuments in North Rhine-Westphalia. Volume 9). 2010, ISBN 978-3-8053-4204-9 , pp. 346-349.

- ↑ Current Biology: A Revised Timescale for Human Evolution Based on Ancient Mitochondrial Genomes . Online at cell.com March 21, 2013.

- ↑ When did modern man leave Africa? ( Memento of the original from May 8, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Archeology online from March 22, 2013.

- ↑ Title page of the special issue Archeology in Germany 10/2016 on aid-magazin.de

Coordinates: 50 ° 42 ′ 51.7 " N , 7 ° 10 ′ 28.7" E