Red chalk

Red chalk (also called “red ocher ”, “red iron ocher ” and red chalk stone ) is a mineral color and consists of a soft mixture of clay and hematite (Fe 2 O 3 ), an iron oxide mineral . The hematite causes the deep red color.

use

Early and prehistory

Red chalk has been used by Neanderthals for 250,000 to 200,000 years.

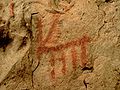

Red chalk has been used for body coloring by Homo sapiens for at least 100,000 years . The body painting served to suppress odor when hunting and as protection from wind, sun, plants and cold. A use to make animal skins more durable is also being discussed. Since a red chalk cover increases the grip of objects, red chalk was used as an additive in gluing techniques for stocks in the Middle Stone Age of South Africa. Already 49,000 years ago binders were used to preserve red chalk paint. B. used from dairy products long before dairy animals were kept. Along with lime and charcoal, red chalk was one of the colors used in cave paintings .

The early use of red chalk is associated with ritual acts and symbolism.

Red chalk was also used to color the deceased and their graves in the band pottery and in the Yamnaja or ocher grave culture . In addition, a wide variety of minerals were used, with ocher in Rixheim, hematite in Elsloo, manganese in Thuringian graves and possibly iron hydroxide in Halle.

history

The Germanic peoples used red chalk to dye runes and breathe life into them for magical purposes. The Greeks used red chalk as a paint to paint ships waterproof. The Romans embellished houses, door posts and ceiling beams with red chalk. During excavations in the Roman vicus Wareswald near Tholey , a red chalk pencil factory established in the 4th century AD was discovered. The red chalk, which was mined in the vicinity until the 20th century, was traded by the Oberthal red chalk merchants throughout Europe.

art

Red chalk, also known as red chalk stone (and red earth ) since the Middle Ages , has been used as a pencil for drawing , especially for sketches and drafts, since the Renaissance , but has also been used in cave paintings in the Altamira cave. Even in the baroque and rococo periods , artists valued the reddish tint. The red chalk markings are not smudge-proof and must be fixed . Today it is less common.

Red chalk is particularly suitable for fine line drawings, portraits, nude drawings and figurative representations. The red chalk used in art today is a fine-grain mineral mixture of clay flakes ( layered silicates ), quartz and feldspar grains and hematite as a color pigment. In the trade, red chalk is offered in the form of square sticks, as a lead for pinch pins and as a wooden pen with a round core made of red chalk.

Extraction

Red chalk mining, sometimes also by mining, has taken place in all parts of the world since the Paleolithic Age . Early Bronze Age red chalk pits are u. a. known from the Greek island of Thasos .

research

Since iron can occur in different oxidation states depending on the moisture, which give off different pigment tones, when looking at and evaluating older or even prehistoric representations using red chalk, it is not certain whether yellow, red, brown or black tones should be displayed there. This often makes it difficult to identify the meaning and requires reconstructions of the oxidation processes.

gallery

Prehistoric cave drawing in Cueva de Bacinete ( Los Barrios )

Leonardo da Vinci , self-portrait , approx. 1512–1515

Johann Heinrich Füssli , The artist desperate in view of the size of the ancient ruins , approx. 1778–1780

Hans von Marées , Study for the painting The Abduction of Ganymede , 1887

Web links

- Information about red chalk at Oberthal Tourismus

- Rötelsteinpfad - hiking trail

- Red chalk: history, material and application in art, J. den Hollander

- Rötel: Historical mining areas with indication of the source literature, J. den Hollander, B. Reissland, N. Wichern, I. Joosten (2019)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Marin Cârciumaru, Elena-Cristina Niţu, Ovidiu Cîrstina: A geode painted with ocher by the Neanderthal man. In: Comptes Rendus Palevol. Volume 14, No. 1, 2015, pp. 31-41.

- ↑ Wil Roebroeks , Mark J. Sier, Trine Kellberg Nielsen, Dimitri De Loecker, Josep Maria Parés, Charles ES Arps, Herman J. Mücher: Use of red ocher by early Neandertals . In: PNAS , 109, No. 6, February 7, 2012, pp. 1889-1894, doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1112261109 .

- ↑ Christopher S. Henshilwood, Francesco d'Errico, Karen L. van Niekerk, Yvan Coquinot, Zenobia Jacobs, Stein-Erik Lauritzen, Michel Menu, Renata García-Moreno: A 100,000-year-old ocher-processing workshop at Blombos Cave, South Africa. In: Science . Volume 334, No. 6053, 2011, pp. 219–222, doi: 10.1126 / science.1211535 .

- ↑ Ian Watts: ocher red, body painting, and language: interpreting the Blombos ocher. In: The cradle of language 2. 2009, pp. 93-129.

- ↑ Helmut Tributsch: Ocher bathing of the bearded vulture: A bio-mimetic model for early humans towards smell prevention and health. In: Animals. Volume 6, No. 1, 2016, p. 7.

- ↑ István E. Sajó, János Kovács, Kathryn E. Fitzsimmons, Viktor Jáger, György Lengyel, Bence Viola, Sahra Talamo, Jean-Jacques Hublin: Core-shell processing of natural pigment: upper Palaeolithic red ocher from Lovas, Hungary. In: PloS one. Volume 10, No. 7, 2015, p. E0131762, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0131762 .

- ↑ Ian Watts: Ocher in the Middle Stone Age of Southern Africa: ritualised display or hide preservative? In: The South African Archaeological Bulletin . 57, No. 175, 2002, pp. 1-14, doi : 10.2307 / 3889102 .

- ↑ Marlize Lombard: The gripping nature of ocher: The association of ocher with Howiesons Poort adhesives and Later Stone Age mastics from South Africa In: Journal of Human Evolution , 53, No. 4, October 1, 2007, pp. 406-419, doi : 10.1016 / j.jhevol.2007.05.004 .

- ^ Lyn Wadley, Bonny Williamson, and Marlize Lombard: Ocher in hafting in Middle Stone Age Southern Africa: A practical role In: Antiquity 78, No. 301, September 2004, pp. 661-675, doi : 10.1017 / S0003598X00113298 .

- ↑ Lyn Wadley: Putting ocher to the test: Replication studies of adhesives that may have been used for hafting tools in the Middle Stone Age In: Journal of Human Evolution , 49, No. 5, November 2005, pp. 587-601, doi : 10.1016 / j.jhevol.2005.06.007 .

- ↑ Marlize Lombard: Direct evidence for the use of ocher in the hafting technology of Middle Stone Age tools from Sibudu Cave In: Southern African Humanities 18, No. 1, November 1, 2006, pp 57-67..

- ↑ Paola Villa, Luca Pollarolo, Ilaria Degano, Leila Birolo, Marco Pasero, Cristian Biagioni, Katerina Douka, Roberto Vinciguerra, Jeannette J. Lucejko, Lyn Wadley: A milk and ocher paint mixture used 49,000 years ago at Sibudu, South Africa. In: PLOSone. June 30, 2015, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0131273 (PDF).

- ↑ a b Simona Petru: Red, black or white? The dawn of color symbolism. In: Documenta Praehistorica. Volume 33, 2006, pp. 203-208.

- ↑ Erella Hovers, Shimon Ilani, Ofer Bar-Yosef, Bernard Vandermeersch: An early case of color symbolism: Ocher use by modern humans in Qafzeh Cave 1. In: Current Anthropology . Volume 44, No. 4, 2003, pp. 491-522.

- ↑ Alexander Marshack: On Paleolithic ocher and the early uses of color and symbol. In: Current Anthropology. Volume 22, No. 2, 1981, pp. 188-191, doi: 10.1086 / 202650 .

- ↑ Eric Glansdorp: Roman age red chalk stick and red chalk powder production in northern Saarland. [Red chalk pens from the Roman vicus Wareswald near Oberthal]. In: E. u. E. Glansdorp (Ed.): Prehistoric and early historical traces in the middle Primstal. Archaeological exhibitions in the local history museum Neipel from 1997 to 2012. (= Archaeological finds in Saarland. 2). Tholey, 2013, ISBN 978-3-00-039212-2 , pp. 253-271.

- ↑ Dieter Lehmann: Two medical prescription books of the 15th century from the Upper Rhine. Part I: Text and Glossary. (= Würzburg medical historical research. 34). Horst Wellm, Pattensen / Han. 1985, ISBN 3-921456-63-0 , p. 241.

- ^ Bernhard D. Haage: A new text testimony to the plague poem of Hans Andree. In: Specialized prose research - Crossing borders. Volume 8/9, 2012/2013, pp. 267–282, here: p. 279 ( rot erde ).

- ^ Ernst E. Wreschner, Ralph Bolton, Karl W. Butzer, Henri Delporte, Alexander Häusler, Albert Heinrich, Anita Jacobson-Widding, Tadeusz Malinowski, Claude Masset, Sheryl F. Miller, Avraham Ronen, Ralph Solecki, Peter H. Stephenson, Lynn L. Thomas, Heinrich Zollinger: Red ocher and human evolution: A case for discussion [and comments and reply]. In: Current Anthropology. Volume 21, No. 5, October 1980, pp. 631-644.

- ↑ Michael D. Stafford, George C. Frison, Dennis Stanford, George Zeimans: Digging for the color of life: Paleoindian red ocher mining at the Powars II site, Platte County, Wyoming, USA. In: Geoarchaeology. Volume 18, No. 1, 2003, pp. 71-90, doi: 10.1002 / gea.10051 .

- ↑ Nerantzis, Stratis Papadopoulos: Copper production during the Early Bronze Age at Aghios Antonios, Potos on Thassos. In: E. Photos-Jones in collaboration with Y. Bassiakos, E. Filippaki, A. Hein, I. Karatasios, V. Kilikoglou, E. Kouloumpi (eds.): BAR S2780 Proceedings of the 6th Symposium of the Hellenic Society for Archaeometry. British Archaeological Reports, 2016, ISBN 978-1-4073-1430-3 , pp. 89-94.

- ↑ Rochelle M. Cornell, Udo Schwertmann: The iron oxides: structure, properties, reactions, occurrences and uses. John Wiley & Sons, 2003.

- ↑ Michael Balter: On the origin of art and symbolism. In: Science. Volume 323, No. 5915, 2009, pp. 709-711.

- ^ Robert G. Bednarik: A taphonomy of palaeoart. In: Antiquity. Volume 68, No. 258, 1994, pp. 68-74.

- ^ Robert G. Bednarik, Kulasekaran Seshadri: Digital color reconstitution in rock art photography. In: Rock Art Research: The Journal of the Australian Rock Art Research Association (AURA). Volume 12, No. 1, 1995, p. 42.