Neanderthals

| Neanderthals | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Reconstruction of a Neanderthal skeleton |

||||||||||||

| temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Pleistocene | ||||||||||||

| 230,000 (130,000) to 30,000 years | ||||||||||||

| localities | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Homo neanderthalensis | ||||||||||||

| Kings , 1864 | ||||||||||||

The Neanderthal (formerly also "Neanderthaler", scientifically Homo neanderthalensis ) is an extinct relative of the anatomically modern human ( Homo sapiens ). It developed in Europe , parallel to Homo sapiens in Africa , from a common African ancestor of the genus Homo - Homo erectus - and temporarily settled large parts of southern , central and eastern Europe . Apparently during the last ice agethe Neanderthals have expanded their originally exclusively European settlement area into western Asia ( Turkey , Levant , northern Iraq ), into parts of central Asia ( Uzbekistan , Tajikistan ) and even into the Altai region. DNA sequencing of the Neanderthal genome revealed evidence of multiple gene flow between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens . The Neanderthals made tools out of stone and wood and, depending on the climatic conditions, subsisted partly on prey and partly on plants. They controlled fire , could communicate in language and were capable of forming symbols.

Neanderthal finds since the Eemian Interglacial (about 130,000 years ago) are referred to as "classical Neanderthals" because of their often distinct anatomical features. Due to at least isolated burials of their dead both in Europe and in western Asia and the depositing of dead people in caves, Homo neanderthalensis is the best preserved species of hominins along with Homo sapiens . There are currently different theories as to why the Neanderthals died out around 40,000 years ago.

naming

The term Neanderthaler goes back to the Neandertal , a valley section of the Düssel between the towns of Erkrath and Mettmann . There, in today's state of North Rhine-Westphalia , the partial skeleton of a Neanderthal was found in 1856 , later named Neandertal 1 . The scientific term Homo neanderthalensis is derived from the Latin hŏmō [ ˈhɔmoː ] "man", the epithet neanderthalensis refers - like the more popular term Neanderthal - to the locality. Homo neanderthalensis means "man from the Neanderthal". The name thus goes back indirectly to Joachim Neander , after whom the "Neandertal" was named. The holotype of Homo neanderthalensis is the Neandertal 1 find .

The naming of the fossil - and thus also of the taxon as a result - as Homo neanderthalensis was made in 1864 by the Irish geologist William King . As early as 1863, in a lecture before the Geological Section of the British Association for the Advancement of Sciences , King had introduced the name "Homo Neanderthalensis King" after discussing the skull shape and its deviations from the skull shape of modern humans . In the German-speaking world, however, Rudolf Virchow retained the upper hand with his misinterpretation of 1872 until his death in 1902. Virchow - the most important German pathologist at the time - considered the find to be a pathologically deformed skull of a modern human being and rejected the thesis of " primitive man ".

The different spellings (epitheton with 'th', Neanderthals only with 't') stem from the fact that in the middle of the 19th century "Neanderthal" was still written with 'th' and this notation was then adopted into the epithet . According to the International Rules for Biological Nomenclature , species names recognized as valid are not subsequently changed. In contrast, the Orthographic Conference of 1901 stipulated in its specifications for the future common German orthography of all German-speaking countries that the hitherto customary 'h' after 't' should be dispensed with in native words (Tal instead of Thal, Tür instead of Thür). For this reason, the popular spelling ("Neanderthaler") that had been common until then was changed to Neanderthaler .

Supported i.a. at a suggestion published by the British paleoanthropologist Bernard G. Campbell in 1973, the Neanderthals were not regarded as a separate species until the 1990s , but as a subspecies of Homo sapiens and were therefore referred to as Homo sapiens neanderthalensis , and the anatomically modern human as Homo sapiens sapiens . However, this naming assumed that according to the biological nomenclature the last common ancestor would be described as (archaic) Homo sapiens ; in fact, however, according to a widespread view, supported by new genetic analyzes (see 2016/17: proof of gene flow to the Neanderthals ), the Homo erectus documented in Africa is the last common ancestor. In addition, the rules of the nomenclature would mean that – as recommended by Günter Bräuer , for example – i.a. the European ancestors of the Neanderthals classified as Homo heidelbergensis would also have to be renamed Homo sapiens . The classification of Neanderthals as a subspecies of Homo sapiens is therefore currently considered outdated; There is "an increasing acceptance that Neanderthals are morphologically distinctive" among paleoanthropologists , which is why the terms Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis have prevailed in the specialist literature.

finds

The oldest evidence for the presence of individuals of the genus Homo outside of Africa are fossil finds from Dmanisi in Georgia , which are approximately 1.85 million years old. The oldest evidence to date of the presence of immigrants of the genus Homo to Europe is 1.2 to 1.1 million years old and comes from the Sima del Elefante site near Atapuerca ( Spain ). Numerous bones, around 900,000 years old, were recovered from the immediately adjacent Gran Dolina site. These fossils are referred to as Homo antecessor by their Spanish discoverers and placed in close proximity to early Neanderthal ancestors. Other researchers interpret these fossils as evidence of early settlement of the Atapuerca region by a population of Homo erectus that later became extinct. Whether there was just one early immigration to Europe or several independently of each other is unclear. In the current specialist literature, it is largely assumed that Europe – long before the immigration of Homo sapiens – was settled by descendants of the African Homo erectus : “The Neanderthals emerged from the European variant of the early humans Homo erectus – known as Homo heidelbergensis .”

Neanderthal

In mid-August 1856, Italian quarry workers discovered some bone fragments in a section of the Neander Valley that had fallen victim to limestone quarrying shortly thereafter . They were initially carelessly thrown into the overburden, but were noticed by the quarry owners Wilhelm Beckershoff and Friedrich Wilhelm Pieper, who had 16 larger pieces of bone recovered and handed them over to Johann Carl Fuhlrott for examination. The Bonn anatomist Hermann Schaaffhausen , who became aware of press reports, also examined the bones and came to the same conclusion as Fuhlrott: It was a prehistoric form of modern man. Fuhlrott and Schaaffhausen presented the find in June 1857 at the general meeting of the Natural History Association of the Prussian Rhineland . However, their interpretation was not shared by the specialist audience. This find, named Neandertal 1, is the type specimen of the species Homo neanderthalensis .

The history of the development of anatomically modern humans and their relationship to Neanderthals is traced in the Neanderthal Museum near the site of the find .

During excavations at the original site in 1997 and 2000, another 60 bone fragments and teeth were discovered that could be attributed to the Neanderthal 1 fossil and two other Neanderthals.

In 2006, a total of 400 Neanderthal fossils were found in Europe.

Other localities

The Neanderthal find was not the first fossil of Homo neanderthalensis to be discovered . As early as 1833, the Dutch doctor and naturalist Philippe-Charles Schmerling described a fossil child's skull and several other bones from a cave near Engis in Belgium, which he assigned to the "Diluvium" (the epoch of the Deluge ) on the basis of animal fossils and stone tools that were also discovered ; however, this 1829 discovered, first scientifically described Neanderthal find ( Engis 2 ) was misjudged by colleagues as "modern".

The relatively well-preserved skull Gibraltar 1 , discovered in 1848 in the limestone quarry Forbes' Quarry in Gibraltar , was only recognized decades later as being thousands of years old and was assigned to the now established species Homo neanderthalensis . The Neanderthals were only finally recognized as an independent human form, deviating from Homo sapiens , after two almost completely preserved Neanderthal skeletons were found in 1886 in a cave in Spy (today a district of Jemeppe-sur-Sambre , Belgium).

By 1999, skeletons and skeletal fragments of more than 300 Neanderthal individuals were known. There are many sites in the karst regions of southern France, such as La Chapelle-aux-Saints , Le Moustier , La Ferrassie , Pech de l'Azé , Arcy-sur-Cure and La Quina . Other significant sites include the Sima de los Huesos , the Cueva de los Aviones , the Cueva Antón and the Cueva de El Sidrón in Spain, the Tabun Cave and the Kebara Cave in the Carmel Mountains in Israel, the Shanidar Cave in Iraq, the Vindija Cave in Croatia, the Karain Cave in Turkey, the Mezmaiskaya Cave in the Russian part of the Caucasus and the Okladnikov Cave in the Altai Mountains.

Overall, the majority of Neanderthal fossils come from France, Italy and Spain, Germany, Belgium and Portugal, in that order; their core area was therefore southern and south-western Europe. From the distribution of the fossil remains known so far, it was deduced that the Neanderthals "extended their originally exclusively European settlement area into the Near East, into parts of Central Asia and even into the Altai region" only during the course of the last Ice Age.

In 2017, Science reported that traces of their mitochondrial DNA could be detected in the sediment of various proven or putative locations of Neanderthals . Neanderthal stone tools had previously been discovered in the Trou al'Wesse cave near Modave in Belgium , but no Neanderthal bones. In 2021, cell nuclear DNA was also detected from cave sediments.

Fossil record and age of finds

The oldest finds in the fossil record , which are classified as Neanderthals by the majority of researchers due to a sufficient number of anatomical peculiarities and are usually referred to as "classic" Neanderthals, come from excavation layers of the oxygen isotope level MIS 5. They come from Croatia ( Krapina ) and Italy and are about 130,000 and 120,000 years old respectively. The eponymous find from the Neandertal was dated to be 42,000 years old.

It is difficult to differentiate between the bone finds associated with the Neanderthals and the older finds formerly referred to as pre-Neanderthals (“Ante-Neanderthals”, “Pre-Neanderthals”, “Proto-Neanderthals”) and today mostly as Homo heidelbergensis , since the Neanderthals were directly and gradually emerged from the chronospecies Homo heidelbergensis . Therefore, different dates are shown in the specialist publications. Frequently, the existence of Neanderthals as a separate taxon is derived from fossils that are between 200,000 and 160,000 years old; However, some fossils that are 300,000 years old and even 500,000 years old have also been attributed to the Neanderthals.

The point in time at which the Neanderthals died out cannot be reliably dated. The widespread view that the Neanderthals were particularly adapted to the cold periods ( stadials ) of the last glacial period that began around 115,000 years ago seems to contradict the fact that they apparently died out during an interstadial , Interstadial 5. This was well before the glacial maximum of the last glacial period, which began around 25,000 years ago and peaked around 20,000 years ago. The distribution of the bone finds was also interpreted to mean that the Neanderthals only left their core area in south-west and south Europe "under favorable climatic and environmental conditions" in order to "penetrate into areas in which they were only temporarily, until the deterioration of those there According to a study published in 2011, the fossils from the Caucasian Mezmaiskaya Cave (39,700 ± 1,100 cal BP ) mark the most recent Neanderthal finds with unequivocal dating. The dating of finds from the Iberian Peninsula that are younger than 45,000 years is also considered doubtful.

The reliability of determining the age of other more recently dated finds is also disputed; this applies in particular to finds from the caves of Arcy-sur-Cure (34,000 years before today = BP ), from the Cueva del Boquete de Zafarraya (32,000 BP) and from the Gorham Cave (28,000 BP). These localities are also all much more southerly and therefore speak more for a cold escape. Dating of Neanderthal fossils younger than 34,000 BP ( 14 C years) is doubted either for methodological reasons or because of the transmission from an unclear layer context. The fossils found in southern Spain may have been underestimated by around 10,000 years due to contamination during sampling; Thomas Higham , a British expert in radiocarbon dating, assumes, based on various age determinations he has made, that the Neanderthals became extinct in Europe no later than 39,000 years ago (cal BP). Also controversial is the assignment of Mousterian -like stone tools to the late Neanderthals, which were discovered at 65° 01′ N (i.e. almost at the Arctic Circle ) in the northern Urals in the Byzovaya site and dated to an age of 34,000 to 31,000 BP.

In Heinrich Event 4 of the most recent ice age (about 40,000 years ago), Homo sapiens advanced north from Africa via the Middle East and subsequently occupied the previous habitat of the Neanderthals. The culture of the Châtelperronian is considered evidence of the cultural influence of the anatomically modern humans ( Homo sapiens ) of the Upper Paleolithic , the so-called Cro-Magnon humans , on the Neanderthals .

anatomy

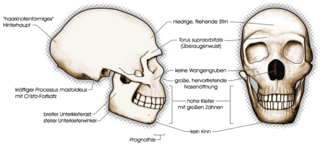

Thanks to the more than 300 skeletal finds, the Neanderthal is the best-studied fossil species of the genus Homo . However, Ian Tattersall pointed out that until the late 1970s there was only "a superficial definition" of this taxon; What was missing, however, was a compilation of those characteristics that distinguish Homo neanderthalensis from all other species of the genus Homo . Albert Santa Luca first presented this in 1978, highlighting four unique features of the Neanderthal skull:

“One was the occipital torus, a bony ridge that runs across the occipital bone at the back of the head. Overlying this bulge is an oval depression ( fossa suprainiaca ), another unique Neanderthal feature. Further forward at the base of the skull is the third feature, a prominent occipito-mastoid crest (now often referred to as the juxtamastoid crest) located in the mastoid process. The mastoid bone is a bony structure that projects behind and below the ear canal (small in Neanderthals compared to anatomically modern humans). Finally, Neanderthals have a distinct, rounded elevation on top of the mastoid process, the mastoid tuberosity. This elevation, which runs obliquely backwards and upwards, is developed differently in other human forms or is absent.”

Later, other typical Neanderthal features were found, such as special structures of the nasal cavity and the position of the semicircular canals of the inner ear . Analyzes of two well-preserved skeletons of Neanderthal newborns showed that Neanderthal bones, which were robust compared to anatomically modern humans, were present before birth.

Neanderthal footprints are known in particular from a dune area of Le Rozel in Normandy (France, around 70,000 years old); there, a group of 10 to 13 mostly very young and juvenile Neanderthals left at least 257 footprints. 87 footprints discovered in 2020 in the Coto de Doñana National Park in southwestern Spain (106,000 ± 19,000 years old) also come from a group of mostly young Neanderthals. A single footprint has also been preserved, for example, from the Vârtop Cave in the Bihor Mountains (Romania at least 62,000, maximum 97,000 years old).

skull bones

The brain volume of the Neanderthals was around 1200 to 1750 cubic centimeters (on average around 1400 cm³), which is slightly larger on average than in modern humans and is interpreted as a consequence of their overall stronger physique. As a result of this range of variation, other features of the skull also show a considerable range of variation. Nevertheless, there are numerous characteristics that differ from those of the anatomically modern human being and which, moreover, did not only develop after birth, but were already present before birth; this could be proven on the skull of the Neanderthal baby from the Mesmaiskaja cave ( Caucasus ).

The skull is elongated from front to back and with its low forehead is also much flatter than that of modern humans, and its elongated shape means that it projects far back and forms a characteristic protrusion there. Due to its two strongly protruding ridges above the eyes, the skull shape appears more archaic than that of most people alive today. The largest skull width is at the level of the lower skull base (in anatomically modern humans: above the ears). Because of this and the relatively low, wide cranium, the outline appears semicircular when viewed from behind (in anatomically modern humans: rounded trapezoidal). The large and wide nostril opening is also noticeable on the facial skull.

The location of the semicircular canals of the inner ear in the petrous bone of the base of the skull is a particularly distinct feature between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens . The semicircular posterior semicircular canal (part of the spinal balance organ) is deeper in Neanderthal than in any other species of the genus Homo . The difference between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens in this trait is about as great as that between Homo sapiens and chimpanzees.

The forehead is flat and receding, while it is mostly steep in European Homo sapiens . The region above the eyes typically shows a clear supraorbital bulge ( torus supraorbitalis ). However, the overeye bulges are not very pronounced in all individuals, also occurred in early Homo sapiens and are therefore not always a reliable criterion for distinguishing Neanderthals and Homo sapiens . This bone thickening is interpreted as a stabilizing adaptation, because the skull was exposed to strong static loads due to the powerful chewing apparatus. The trait appeared in the common ancestors of Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans, and can also be observed in the great apes.

The nostrils are large and relatively wide, the bridge of the nose very strong and also wide. In contrast to modern Europeans , the nasal floor is rounded off at the level of the face. These features indicate a large, fleshy nose, which - like some other internal nasal features - is interpreted by some researchers as an adaptation to the Ice Age cold periods: A large nose preheats the breathing air before it reaches the lungs , and thus supports this maintaining core body temperature. In addition, the olfactory mucosa was located further forward in the nose than in Homo sapiens : "The resulting improved absorption of smells could have been an advantage when locating food in general and especially when hunting animals." However, it was also argued that the larger noses and the more spacious maxillary and frontal sinuses of the Neanderthals were less an adaptation to cold periods than primarily a consequence of their overall somewhat broader faces.

teeth

Based on the wear of the teeth, it was concluded that the Krapina Neanderthals did not live longer than 30 years; only marginally longer lifespans have also been reported for the fossils of Homo heidelbergensis from the Sima de los Huesos in Spain.

The upper and lower jaw bones are higher and also longer than in anatomically modern humans; Neanderthals also have larger incisors but narrower molars than Homo sapiens . Due to the stronger and larger jawbones , Neanderthal skulls appear prognathic , i. H. the lower half of the face protrudes clearly. The ascending mandibular rami are wider, the angle between mandibular rami and body steeper. A striking distinguishing feature from anatomically modern humans is the lack of a clearly protruding chin in most Neanderthal skulls .

The number of teeth and the shape of the crown correspond to those of Homo sapiens , but the upper incisors are shovel-shaped. The molars often have a hump in the middle, which does not occur in anatomically modern humans. The back molars are sometimes - not always - characterized by taurodontia . H. the roots separate into branches just before the tips. Special diagnostic features can also be found on the lower fourth premolars , the first molars and second deciduous molars, which has led to extensive comparative studies of late Middle Palaeolithic and early Upper Palaeolithic tooth finds to distinguish between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans. In addition, the so-called retromolar gap (“Neanderthal gap”, not to be confused with the diastema ) is typical, which regularly occurs between the last molar (back tooth) and the mandibular ramus.

One hypothesis assumes that the shape of the skull was not only formed passively by the growing brain, but later also came about through the heavy use of the incisors. Accordingly, these were not only used for eating, but also as a "tool" and as a kind of "third hand". FH Smith 's so-called teeth -as-tool hypothesis states that the teeth were used as a vise and pliers . However, this technique is not a unique feature of the Neanderthals, but is both pathologically and ethnographically proven in modern humans. Traces of abrasion on the teeth indicate that the Neanderthals - like Homo heidelbergensis - were predominantly right-handed.

torso, arms and legs

Many Neanderthal finds come from burials , which is why all parts of their bodies have been preserved multiple times and in good condition. The typical European - the so-called classical - Neanderthal skeletons " look more or less the same as the skeletons of modern humans. The main differences are in the proportions. Neanderthals have a much broader, sturdier pelvis and leg bones than modern humans. In contrast, the arms were comparatively delicately built. From the muscle attachment marks of the hands it was deduced that Neanderthals primarily used precision grips in their manual activities .

The bone finds suggest a height of about 1.60 m; the Neanderthals were therefore somewhat smaller than the early anatomically modern humans , for whom a body height of approx. 1.77 m was reconstructed. Their body weight , on the other hand, roughly corresponded to that of Europeans living today: the so-called Old Man of La Chapelle , a skull with associated lower jaw and numerous other body bones found in La Chapelle-aux-Saints ( Corrèze department , France) in 1908 has a body weight of 60 to 80 kg attributed; the female skull Gibraltar 1 discovered in Gibraltar in Forbes' Quarry in 1848 is attributed a body weight of 50 to 70 kg. The body height of Neanderthal women was about 95 percent of the average height of Neanderthal men and thus corresponds to the proportions of modern humans. The pelvic canal of Neanderthal women was built as narrow as that of anatomically modern women.

Given that the Neanderthals lived during an Ice Age, such differences have been interpreted as an adaptation to the cold climate of Europe. Finds from warmer regions (e.g. the Middle East) indicate larger and slimmer individuals. Since there was only a short space between the chest and hips of the Neanderthals and the chest cavity was larger than in Homo sapiens due to a deviating curvature of the ribs from the anatomically modern human , their torso appeared more compact, stockier - "barrel-shaped" - than the torso of today's Europeans; this is also considered to be the main reason for the smaller average body size of the Neanderthals compared to humans living today.

The deviations of certain features of the legs from modern man are also interpreted as an adaptation of the physique to a relatively cold climate; Friedemann Schrenk illustrated this using the example of Africans , Lapps and Neanderthals:

“While the length of the lower leg corresponds to 79 percent of the thigh in the 'Lapps', this value is 86 percent in Africans; these have much longer lower legs. Neanderthal lower legs were only 71 percent of thigh length, so Neanderthals had significantly shorter legs than modern Lapland humans .”

In addition to these length ratios, which differed from those of Homo sapiens , the bones of the lower extremities in the Neanderthals were also able to cope with much greater loads:

“[ Femur and tibia ] suggest a doubling of flexural and torsional strength compared to the modern human lower extremity. The morphology of the knee area indicates considerable strength and loading capacity. After all, the foot was extremely resilient due to enlarged joints and a reinforced big toe.”

However, it was deduced from the length of his Achilles tendon that the Neanderthals were not as good endurance runners and used more energy than modern humans even when running short distances.

From the surviving muscle marks (where the muscles attach to the bone) it could be deduced that the Neanderthals had unusually strong chest and back muscles compared to modern humans, so that the arms “ also allowed an extremely strong grip ”; the hand bones also indicate a "precision grip". From these muscle marks and the weight of the bone finds - the ribs and pelvic girdle were also more massive than in modern humans - it was possible to deduce the body weight, which at 50 to 80 kg is relatively high in relation to body size and compared to modern humans.

The image of the clumsy primitive that was often depicted in the past, who can hardly walk upright, has long been outdated, because the body dimensions of the Neanderthals – despite all the deviations – are still within the range of variation of modern humans.

Anatomical findings on development and social behavior

Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology used impressions of the brain on the inside of the cranial bones to show that the growth pattern of the Neanderthal brain in the first year of life - a critical phase for cognitive development - differed significantly from that of anatomically modern humans difference. Accordingly, the slightly different shape of the brain (spherical in modern humans, oblong in Neanderthals) probably had an impact on cognitive abilities. In the Neanderthal child, for example, areas of the parietal lobe and the cerebellum region developed less strongly than in the young Homo sapiens, but similarly to the chimpanzee. In modern humans, when these regions are injured or reduced in size as a result of developmental disabilities, this can lead to limitations in speech and social behavior.

In a laboratory experiment, cell biologists integrated the variant of the gene NOVA1 , which had been reconstructed for Neanderthals, into the stem cells of modern humans; this gene is known to regulate brain function in early stages of development . As a result, an “ organoid ” grew up with characteristics that differed significantly from an unmodified organoid: it had a different shape, and “the way the cells spread out, how the synapses form as the junctions of the neurons, and also from which proteins the synapses are constructed”, was also different. From this, the researchers concluded that the Neanderthal brain was noticeably different from that of Homo sapiens .

In 2010, synchrotron radiation was used to reconstruct the period within which the teeth of Neanderthal children developed; this applies to anatomically modern humans as a benchmark for the general speed of development of a child. Accordingly, the development speed of the young Neanderthals was much faster - and the phase of childhood therefore shorter - than in humans. However, the development of the brain in early childhood was probably similar to that in anatomically modern humans, and according to a study published in 2017, the enlargement of the bones below the head was also similar to that in humans; this was interpreted as an indication of a possibly similarly long childhood as in humans.

The right humerus and the muscle attachments on the right side of the upper arm of Neanderthals were generally stronger than the left ones. This is often attributed to the regular use of spears; However, a study published in 2012 suggested that this pronounced asymmetry could be primarily a consequence of the frequent processing of surfaces (smoothing the floor, furs).

Numerous skeletons of older Neanderthals show healed fractures and evidence of severe muscle atrophy as a result of injuries that severely weakened them. This has been interpreted to mean that they could only survive the aftermath of these injuries because they had the support of clan members.

Evidence of cannibalism has been found in the Goyet Caves in Gesves ( Belgium ), as has previously been found in archaeological sites in France and Spain .

Life expectancy

The age at death can be reconstructed quite accurately for individual bone finds. However, a reliable mean value for the life expectancy of the entire Neanderthal population cannot be calculated from this. Nevertheless, there are indications of life expectancy. According to Friedemann Schrenk , an examination of “a total of 220 skeletons from the entire distribution area of the Neanderthals from a period between 100,000 and 35,000 years ago showed […] that 80 percent of all Neanderthals died before the age of 40”; most of them even died between the ages of 20 and 30. According to Schrenk, however, some people had an “astonishingly high life expectancy”, especially given the harsh living conditions: it is certain, for example, that the so-called Old Man of La Chapelle was around 40 to 45 years old when he died. Nevertheless, these findings indicate that only a few people lived to see their grandchildren grow up. (Cf. also grandmother hypothesis )

nutrition

The teeth of modern humans and macaques exhibit a characteristic that correlates closely with the timing of weaning : the ratio of barium to calcium in tooth enamel . An analysis of this ratio in a Neanderthal tooth in 2013 revealed that this Neanderthal had been weaned around the age of 14 to 15 months. However, the examination of two Neanderthal teeth from the French site of Payre (municipality of Rompon , Ardèche department ) in 2018 revealed an age of 2 ½ years for the time of weaning; In 1997, the age at weaning was estimated at three years. A study published in 2020 on three Neanderthal teeth from Italy, around 70,000 to 50,000 years old, showed an age of only 5 to 6 months for weaning.

What is certain is that the Neanderthals regularly kindled fires at their dwelling places ; the oldest fireplaces in Europe that are considered certain come from Homo heidelbergensis and are around 400,000 years old. Ash deposits from a plethora of hearths discovered at Kebara Cave were particularly revealing: “Each settlement phase left a layer of debris in the cave; dust blew in between dwellings and rock material fell from the ceiling. Sediments several meters thick have accumulated in Kebara, in which successive inspection horizons could be distinguished precisely in the central area, where the hearths were located.” Similar finds were uncovered in Spain in the Abric Romaní , a rocky outcrop (abri) that – with interruptions – covered more than been inhabited for 20,000 years.

Findings of hunting grounds in France, in the Caucasus and near Wallertheim in the Rhineland as well as in the Buhlen hunting station prove “that Neanderthals were specialized hunters who repeatedly ambushed and killed bison or mammoths on their way to winter pastures in the same places. Bone remains from 86 hunted reindeer were found in Salzgitter-Lebenstedt along with thousands of stone tools , a clear testament to the excellent hunting skills of the Neanderthals.” Isotope measurements of collagen in Neanderthal bones from the Vindija Cave in Croatia also indicated that meat was the main source for protein was; Isotope measurements on several Neanderthal finds from France have been interpreted to mean that these Neanderthals were " apex predators ". Such findings led, among other things, to the assumption that the extinction of the Neanderthals could have been partly caused by a less flexible diet than that of Homo sapiens .

In 2010, however, this hypothesis was weakened when an international team of researchers from George Washington University 's Center for Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology found numerous plant microfossils in the calculus of Neanderthal teeth from Belgium and Iraq . Accordingly, among other things , dates , legumes and grass seeds were consumed. Furthermore, the calculus-embedded starch of northern Spanish Neanderthals was found to show characteristics of being altered by heating; their vegetable diet was consequently made more digestible by cooking, and consisted at least in part of species that can be interpreted as medicinal or aromatic plants. Traces of abrasion on the tooth surface of Neanderthals from different epochs (cold periods and warm periods) also show that they adapted their food intake to the available plants depending on the climatic and, at the same time, ecological conditions. Independently of these findings, it was also possible to reconstruct from around 50,000-year-old faeces of Spanish Neanderthals - based on preserved 5β-stigmasterin - that in addition to frequent meat consumption, a considerable proportion of plant-based food was consumed. An isotopic study of the skeletal remains of Spy (now a part of Jemeppe-sur-Sambre in Belgium ) revealed that around 20 percent of the protein intake was of plant origin, which also means that this population had a higher proportion of meat in their diet than the populations in Spain.

A working group from the Senckenberg Research Institute came to similar conclusions when they analyzed the wear and tear of 73 molars from the upper jaws of Neanderthals and modern humans: the grinding of food changes the surface of the teeth depending on the type of food. The study results "clearly show that the diet of both members of the genus Homo was varied overall." It was also shown that the composition of the diet "depended on the eco-geographical conditions in each case." According to this study, the proportion of meat in the diet was also in the Neanderthals living in Northern Europe much higher than in the Neanderthals living in Southern Europe. The diet of the Neanderthals was therefore just as variable and varied as that of the early European Homo sapiens .

The oldest evidence to date of the consumption of snails and mussels comes from the Bajondillo Cave ( Torremolinos , Spain); they have been assigned to the oxygen isotope level MIS 6 and dated to be 150,000 years old. Evidence of Neanderthal adaptation to eco-geographical conditions was also discovered in the offshore Vanguard Cave and Gorham Cave in Gibraltar , also offshore, along with Mousterian stone tools: shells of Adriatic mussels ( Mytilus galloprovincialis ) and bones of seals , Dolphins and fish bear witness to the consumption of sea creatures for thousands of years. Evidence of the consumption of sea creatures dating back around 100,000 years was also discovered in the Serra da Arrábida in Portugal. Ear canal exostoses in some of the skulls examined were interpreted as independent confirmation that Neanderthals could also obtain food under water. The oldest evidence of Neanderthals eating pigeons also comes from Gorham Cave; the surviving bones of these birds show both cut and burn marks.

Culture

overview

Habitat and culture of Homo neanderthalensis extended - especially in the phase as "classic Neanderthal" since the Eemian interglacial period about 125,000 years ago - over large parts of Europe to the Levant in the Middle East and beyond the Crimean Peninsula to the edge According to archaeological findings, Siberia was probably settled in two waves. These early Europeans lived in labor groups. The Neanderthals are associated in particular with the cultural area of the Mousterian (125,000 to 40,000 years ago) with e.g. Micoquian and Levallois techniques of working stone - until their disappearance in the early Aurignacian , when the anatomically modern Homo sapiens ( Cro-Magnon man ) had already immigrated to Europe. The hordes settled z. T. widely scattered, and it cannot be assumed that there is a uniform way of life in this huge area. A uniform appearance of the individuals is also unlikely, although isolated genetic traces for red hair and lighter pigmentation have been demonstrated.

Regionally different conditions determined the everyday life of the Neanderthals: climate, terrain and seasons, sources of drinking water and the availability of huntable game and other food, especially places where raw materials for stone tools were found. Some groups preferred to stay in caves and grottos or under rock shelters (rock overhangs) - e.g. B. in the Dordogne ( Le Moustier , La Ferrassie ) but also in the Small Feldhofer Grotto in the Neandertal . Others lived on the plains or in forests and built shelters out of skins or shrubs and branches. There were also dwellings supported by mammoth bones and tusks, e.g. B. in Netzetal (Hesse). Shallow pits with round support holes and hearths were found in Rheindahlen near Mönchengladbach, stone artefacts from several zones were found on a forecourt: coarsely dissected stone nodules and finely worked edges through retouching. These finds date from the Eem Interglacial . In the Ukraine , too, there were outdoor stations with evidence of fireplaces.

Traces of pyrite have been found on hand axes and flakes in France . Scientists who replicated those tools and used them to create fire (which also led to traces of pyrite on the tools) concluded that axes and other stone tools were sometimes used multifunctionally by Neanderthals.

In the Middle East, Neanderthals showed different migratory behavior: On the one hand, there were circular migration strategies from place to place, on the other hand, star-shaped migrations from the base camp to peripheral places with raw material deposits. In the Middle Paleolithic , the Neanderthals deliberately sought out larger deposits of flint and quartzite , in some places over ten thousand years. There are also references to woodworking and the use of wooden lances, e.g. B. a 2.45 meter long yew lance, with which forest elephants were killed 120,000 years ago. Wooden, sharpened javelins, occasionally tipped with stone, were also used.

Analyzes of the genomes of two Neanderthals from Germany and Belgium who were around 120,000 years old showed that the last Neanderthals who lived in Europe around 40,000 years ago descended at least in part from these European Neanderthals who were around 80,000 years older. At the same time, the analyzes revealed that the two 120,000-year-old individuals were less closely related to the Neanderthals living in Siberia at the same time, which means that the Neanderthal populations in Europe and Siberia had hardly any contact with each other as early as 120,000 years ago.

Some sites document the hunting of individual animals, in other places there is evidence of mass hunting: at the Salzgitter-Lebenstedt site , Neanderthals had set up special hunting camps; the remains of hunted animals with slaughter marks from 86 reindeer and thousands of stone implements were found here. The hunting period can be determined by examining the teeth and the development of the antlers in the autumn. Medium-sized mammals such as horses, wild donkeys and reindeer were often killed and dismembered individually, and the parts were taken to their living quarters. Large mammals (elephant, rhinoceros) were driven over limestone cliffs on what is now the island of Jersey. Mass killings and long-term stockpiling of meat only make sense if the hunters were aware of methods of preservation.

The type of stone tools and weapons used depended on the availability of raw materials, tradition and individual skill. There were Neanderthals who preferred to settle near quarries; others traveled great distances to flint deposits to obtain raw material. Groups staying at the craters of the East Eifel volcanoes had tools made of flint with them, the closest occurrence of which was in the Meuse region (near Aachen and Maastricht), but also so-called Baltic flint from the Ruhr area. These sites were corner points of a home range of more than 100 km in diameter. Stone tools and weapons now associated with specific cultures or processing techniques (axes, flakes , scrapers , points ) were not always used by all Neanderthal groups, and not always at the same time. Some were predominantly found in a particular region. Towards the end of their existence, Neanderthal techniques may have been influenced by Cro-Magnon immigrant tools and ornaments.

language

In 1983, the only hyoid bone of a Neanderthal man was discovered in the Kebara Cave in Israel 's Carmel Mountains . It corresponds to that of modern humans and is considered the most important indication that the Neanderthals had the anatomical prerequisites for the ability to speak . In October 2007, paleogenetic studies also revealed that Neanderthals had the same FOXP2 gene as modern humans. The FOXP2 gene, thought to be important for the development of language, was isolated and analyzed by DNA sequencing from Neanderthal bones found in a Spanish cave. A reconstruction of the sound transmission to the inner ear in five Neanderthal skulls also showed that the width of the frequency band of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals hardly differs; at the same time, however, considerable differences between Neanderthals and their forerunners ( Homo heidelbergensis ) were demonstrated. From this it was concluded that Neanderthals could hear spoken language just as well as humans living today. While more evidence is needed, there is no reason to believe that Neanderthals could not speak. Katarina Harvati and Maria Kirady speculate that there was probably no "common language" understood by all Neanderthals and that the idioms were probably structured differently than in Homo sapiens .

tool use

In Europe, the Mousterian era and the stone tools made using the Levallois technique are associated with the Neanderthals. For the “classic” Neanderthals of the Würm and Vistula glacial periods , the universal tool for cutting and scraping was the wedge knife , which was also the typological model of the Micoquien (today: “wedge knife groups”). A modern counterpart of this type of device, which was used both for cutting and scraping, has been handed down to the Eskimos with the ulu . The sites of tools used during the Mousterian period are often only five or six kilometers from the natural deposits of the rocks from which they were made; From this finding it was concluded that these Neanderthal groups lived in a relatively small area. Other groups traveled great distances to flint deposits to obtain the raw material. Some sites were corner points of a home range of more than 100 km in diameter.

As evidenced by the approximately 120,000-year-old spear found by apprentices in 1946 , Neanderthals used wooden weapons ( pikes ) to kill big game. In 2018, hunting injuries were found on two 120,000-year-old fallow deer skeletons recovered near Halle (Saale) . Using an experimental ballistics set-up, "the use of a wooden javelin in upward motion, deployed at low speed" was reconstructed; this indicates “that Neanderthals approached the animals from a very short distance and used the spear as a thrusting weapon and not as a throwing weapon. Such a confrontational type of hunt required careful planning, camouflage and close cooperation between the individual hunters.” Since 1994, eight spears from the Holstein interglacial period ( Schöninger Speere ), which are around 300,000 years old and were used as throwing spears , have also been found in the Schöningen opencast mine be interpreted. Experiments with javelins show that they can be used accurately at a distance of 20 meters or more. Experiments from a distance of 5 m resulted in average penetration depths of 23.8 cm at average impact speeds of 83 km/h and a penetration force of 25.9 N . It is very probable that lances were reinforced with blade tips for the late Neanderthals, and the stocking of wooden weapons with Levallois tips has also been proven in several cases. At the Poggetti Vecchi site in the province of Grosseto (Italy), several dozen 171,000-year-old fire-hardened burial sticks were recovered, made mostly from boxwood ( Buxus sempervirens ), but also from oak , juniper and ash . The use of toothpicks is also considered safe.

Neanderthals from the Königsaue site on the Ascherslebener See (Harz foreland) used birch pitch to glue stone artefacts into wooden shafts. Another find of birch pitch on a stone artefact around 50,000 years old was reported from the Netherlands. For the distillation of the pitch from birch bark by smoldering in the absence of air, a constant temperature of about 350 °C is necessary for a longer period of time; however, a less complex procedure (without air exclusion) could also have led to success.

The grinding tools ( smoothers ) made of deer bones discovered in the south-west of France in the Abri Peyrony and Pech-de-l'Azé excavation sites , which have been dated to be up to 50,000 years old, are similar to the smoothing woods ( lissoirs ) used to this day, with which leather is processed. These so far oldest special tools in Europe served to soften the leather and increase its water resistance by scraping, grinding and polishing. According to the researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, this might be evidence that the Neanderthals already had their own technology, the emergence of which was previously attributed to modern humans, but which they could also have adopted from Neanderthals. When they immigrated to Europe, they only knew pointed bone tools, but a short time later they made lissoirs.

clothing

Neanderthals were believed to be the first human species to make clothing, but unlike Cro-Magnon humans , no evidence of the manufacture and use of needles has yet been discovered among them. In the Abri du Maras (at the end of the Gorges de l'Ardèche , Ardèche department , France), however, plant fibers twisted into threads were discovered in the immediate vicinity of stone tools, which do not occur in nature in such a state, are 40,000 to 50,000 years old and due to of this dating were attributed to the Neanderthals. From Neumark-Nord , an approx. 200,000-year-old site on a former lake shore near Frankleben in Saxony-Anhalt , comes a stone tool with adhering residues of oak acid in a concentration that cannot occur naturally and is therefore considered an indication of the tanning of animal skins is interpreted. Numerous footprints were found at the Le Rozel beach site , some of which are believed to be from light footwear.

It was also derived from model calculations that the Neanderthals probably made and wore clothing. According to the calculations, a clothed Neanderthal with a body weight of 80 kg would have had to produce an additional 50 kg of subcutaneous fat tissue during the cold periods of the time in order to withstand the cold without clothing. As Ian Tattersall comments: "Being built like a sumo wrestler is hardly what can be considered an ideal adaptation to a hunter's lifestyle."

Sites on the Crimean Peninsula

Some archaeological sites on the Crimean Peninsula show cultural layers from the Eemian Interglacial (125,000 years before today) to the extinction of the Neanderthals around 30,000 years ago. Accordingly, the tool culture remained largely unchanged for several tens of thousands of years: flat blades, which were mostly kept functional on both sides for a long time by surface retouching. They were located in side handle shafts made of wood or bone and were partly retouched in the assembled state. This culture, called “ Ak Kaya industry ”, is similar to the industry of the Micoquien of Central Europe , which is also attributed to the Neanderthals . With the drop in temperature to the first maximum of the last ice age around 60,000 years ago, the culture changed: tools made of flint were now produced using cutting techniques, which were thrown away after wear and were not retouched. The culture of the late Neanderthals was therefore similar to the Aurignacian of Homo sapiens in Central Europe, although this is only documented in Crimea 30,000 years ago. The Neanderthals had therefore anticipated important innovations of modern man in the Crimea.

The numerous bone finds of wild donkeys at the Kabazi site make it clear that the Neanderthals were able to plan their raids. The finds were interpreted to mean that entire families or herds of donkeys with parents and young animals were captured while they were drinking from the nearby river. The prey was butchered on the spot, but substantial parts of the animals were transported away in one piece and cut up, prepared and eaten elsewhere. A division of labor across different camp sites has also been proven: There were camp sites where the game was cut up and the stone tools made, as well as others where people obviously lived longer and ate more frequently. A clear, planned division of labor and organization, a seasonal specialization in individual animal species and seasonal camp sites related to the whole group could be identified. The researchers gained the impression of Middle Palaeolithic people who had already developed certain Upper Palaeolithic achievements but were not yet familiar with others: typical Upper Palaeolithic features such as special antler and bone processing and tools such as gravers and scrapers were not found.

At the site of Kiik-Koba , a large cave in the Crimean Mountains (44°57' N, 34°21' E), a flint with scratches was recovered, the find layer of which was found to be 35,000 to 37,000 years old (35 to 37 cal kyr BP) was dated; the scratches were interpreted as possibly deliberately designed figurative engraving.

Sites in Germany and Austria

The best-known site in Germany is the Neandertal , where only a few stone tools were found, which were not directly related to the Neandertal 1 fossil that gave it its name .

On the other hand, an important site in Germany is the Balver Cave in Westphalia, because it was frequently visited by Neanderthals in the first half of the Vistula glaciation 100,000 to 40,000 years ago. In addition to numerous stone artefacts, many tools made of bone and mammoth ivory were identified in the finds from the Balver Cave. The sediment of the cave was also interspersed with the bones of mammoths, especially calves and young animals; it is believed that the very large number of animals around the cave were killed. In the Gudenus Cave (Kleines Kremstal , Lower Austria), the lower, 70,000-year-old cultural layer indicates hunting of mammoths , woolly rhinos , reindeer , wild horses and cave bears . Due to the frequent head and arm injuries on Neanderthal skeletons, one concludes that the big game was hunted with close-range weapons, as evidenced by the find of a wooden spearhead.

Possible seafaring (in Greece)

Evidence of early seafaring Neanderthals has been found in the eastern Mediterranean region, where Neanderthals and their ancestors ( Homo heidelbergensis ) had lived for around 300,000 years. However, their typical Mousterian stone tools have not only been found on mainland Greece, but - dated to be at least 110,000 years old - also on the Greek islands of Lefkada , Kefalonia and Zakynthos . With the exception of Lefkada – a peninsula on the Greek mainland during the Ice Age when the sea level was up to 120 meters lower – Kefalonia and Zakynthos including Ithaca formed a single large island during these times. It was surrounded by water at least 180 meters deep and could probably only be reached by watercraft; the distance to the mainland at that time was about 5 to 7.5 kilometers to the southern tip of the Lefkada peninsula.

As early as 2008 and 2009, researchers led by Thomas Strasser from Providence College found 130,000-year-old stone tools in the Megalopotamos gorge on Crete , above the palm-lined beach of Preveli ; these tools also come from an epoch in which Homo sapiens was not yet settled in Europe. Crete has been completely surrounded by water for around 5.3 million years, the nearest land was around 40 kilometers away even during the ice ages. However, Strasser does not assign the finds on Crete to Homo neanderthalensis , but to Homo heidelbergensis or Homo erectus .

Stone tools from the Middle Paleolithic have also been found on Naxos ; It is unclear whether this island was at least temporarily accessible from the mainland with dry feet during the ice ages. In 2019, the finds were reported to be around 200,000 years old.

In Asia, Homo erectus was only able to colonize the island of Flores after using watercraft to cross several waterways that existed between the neighboring islands around a million years ago (cf. Homo floresiensis ).

Body jewelry, symbolic thinking

Several mussel shells were discovered in two caves in south-east Spain, which (without the help of their collectors) have 5 mm holes in the area of their vertebrae and, according to radiocarbon dating , are 45,000 to 50,000 years old; both caves are known to be the abodes of Neanderthals. The shell of a large scallop from Cueva Antón is painted on its outside with orange pigment , several shells from Cueva de los Aviones have red, yellow and orange pigments. Further remains of red and yellow paint were also found in their vicinity. These finds have been interpreted as evidence that the authors of the finds used the shells and pigments "in an aesthetic and presumably symbolic" manner - possibly attached to a necklace. According to a study published in 2018, the finds from the Cueva de los Aviones are even 115,000 to 120,000 years old according to uranium-thorium dating .

Also attributed to a Neanderthal is the La Roche-Cotard mask found in France . Furthermore, in France, during excavations in Pech de l'Azé , manganese-containing pigment clumps were found, which suggest Neanderthal body painting. Most finds of color pigments date from the epoch 60,000 to 40,000 years ago; the oldest find - red ochre , whose use is unclear - comes from Maastricht -Belvédère and is 250,000 to 200,000 years old, about as old as pigment finds from Africa, which are attributed to early Homo sapiens .

In the Italian Grotta di Fumane (Fumane Cave ) , 18 km northwest of Verona, 44,000-year-old evidence of the removal of large feathers from bird species that were not eaten, such as bearded vultures or red- footed hawks , has been found . Signs of body painting were also found.

Eight claws of white- tailed eagles obtained from the Krapina excavations were evaluated as pieces of jewelery in 2015: examination with light microscopy ruled out indented and polished areas on the claws from natural origin or accidental influences and led to the conclusion that the claws were considered decorative Parts of a necklace were used. From this, the authors concluded that objects were used symbolically by Neanderthals in Europe 130,000 years ago and thus before their contact with modern humans. This interpretation was supported in 2019 by evidence of cut marks on golden eagle wing bones (on bones that hardly put on flesh) from other sites in central and western Europe, which were evaluated as evidence of careful separation of the feathers from the bones. This gave the authors reason to suspect that the feathers could have served as ornaments. Cut marks were also found on a toe bone from the Foradada Cave in Calafell (Spain), which is probably attributable to a Spanish imperial eagle .

Also, “an angular pattern of six notches” on the giant deer bone from the Einhorn Cave in the Harz Mountains was scratched by a Neanderthal at least 51,000 years ago.

cave painting

The oldest known cave paintings from Europe are around 65,000 years old. An international team of researchers led by Dirk Hoffmann from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology reported in 2018 that Neanderthals in Europe created cave art more than 20,000 years before the arrival of anatomically modern humans in Europe 40,000 years ago. The researchers had analyzed, using uranium-thorium dating , 60 samples of carbonate crusts on the color pigments of paintings in three caves in Spain: from the Cueva de La Pasiega in the municipality of Puente Viesgo , the Maltravieso Cave in the municipality of Cáceres and the Cave of Ardales (in the municipality of Ardales ). "They usually contain red, sometimes black, paintings that include groups of animals, dots, geometric signs, positive and negative handprints, and also rock carvings." However, another scholarly publication later suggested that the dating might be wrong, and that for some paintings a natural-geological cause cannot be ruled out. Results of a study published in 2021 disproved this theory. Using X-ray spectroscopy , micro -Raman spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction , a natural-geological cause could be ruled out and the paint layers identified as cave paintings.

For a long time, science assumed that men had artistically depicted their hunting experiences in the paintings, but there was no evidence for this. Pennsylvania State University archaeologist Dean Snow analyzed handprints from eight French and Spanish Stone Age caves, including El Castillo Cave, and found that about three-fourths of all colored hands are female, and there are also numerous handprints from children and adolescents .

Spatially differentiated use of caves

Neanderthals apparently lived on three levels in the rock overhang Bombrini in northwestern Italy, which has been referred to as a logistical base camp. Each of these levels contained artifacts that allowed inferring a division into rooms used for slaughter, habitation, and tool-making.

In a cave near Bruniquel in southern France , numerous fragments of more than 400 stalagmites , which were deliberately broken off, were discovered, which are arranged in two rings of 6.70 and 4.50 meters in circumference ( stone circles in the Bruniquel cave ). These constructions were erected 176,500 ± 2100 years ago, some 330 meters from the cave entrance. The function of these rings is unclear, but a thumb-sized charred piece of bone was discovered, suggesting that food may have been prepared here. However, this cannot explain why the Neanderthals went to such great lengths to equip such a remote, difficult-to-reach place.

burials

Due to at least isolated burials of their dead both in Europe and in the Middle East and the laying of dead people in caves, Homo neanderthalensis is the fossil best preserved species of hominins next to Homo sapiens . “The deceased was usually laid in the grave on his back or in a squat position – i.e. lying on his side with his legs drawn up. Red chalk and ocher colored pigment remains have been identified in the tombs at La Ferrassie , Spy and La Chapelle-aux-Saints . The importance of colors in Neanderthal burials and the cult practices that led to the use of natural pigments are unknown. ”

“Upper Paleolithic tombs were often very complex, with richly decorated bodies and numerous grave goods. Objects interpreted in this way in Mousterian tombs, on the other hand, were mostly everyday objects such as stone tools and individual animal bones. These could have been intended as equipment and for provisions in later life, but it is also conceivable that they ended up in the grave more or less by accident as ubiquitous objects in the living room. There are few things in Mousterian tombs whose interpretation as 'grave goods' stands up to critical analysis.”

As early as 1945, for example, the grave of a nine-year-old Neanderthal boy discovered in the Teschik-Tash Cave in Uzbekistan was described; the child's skeleton lay there for around 70,000 years, surrounded by ibex horns.

Several Neanderthal burial sites in the Shanidar Cave ( Iraq ) are about the same age . An unusually high concentration of bee pollen was found in Grave IV , which has occasionally been interpreted as evidence "of shamanism and ritualized burials"; however, the flowers could also have been carried into the cave by the Persian gerbils , which are often found there , and buried in the burial horizon. There are also Neanderthal finds that have been controversially discussed as burials or deposits in pits in the Abri La Ferrassie (south-western France). Burial finds from the Spanish cave Sima de las Palomas del Cabezo Gordo became known in 2011. The so-called Old Man of La Chapelle was also recovered from a pit "whose filling is clearly different in color from the surrounding sediment."

Bones of cave bears in the Swiss Drachenloch cave , arranged between stone slabs, were the cause of a bear cult attributed to the Neanderthals . Of course, the rocks can also have fallen from the cave ceiling without human intervention, and the “aligned” appearance of the finds can have been caused by the effects of water. Since there is no further evidence of a bear cult that early (e.g. ritual objects, communal burials, etc.) and existing bear cults are very complex, its existence is now considered unlikely or refuted.

reproduction and population density

Genetic analyzes of tooth finds in the Spanish El Sidron Cave indicate a patrilocal reproductive behavior of the Neanderthals. Carles Lalueza-Fox from the Institute for Evolutionary Biology in Barcelona, who carried out these analyzes using mitochondrial DNA on a 12-member family-related Neanderthal group, interprets this as a social practice of Neanderthals, which also occurs in modern hunter-gatherer cultures. namely, that the females left their original groups while the males remained in the father's group. However , it has not yet been conclusively clarified whether this leads to the conclusion that the Neanderthals had a consistently patrilineal social practice. The lineages within the group, which were carried out on the basis of the mtDNA analysis, also make a birth frequency of the Neanderthals of about 3 years seem plausible.

Based on the DNA of the mitochondria ( mtDNA ) of five Neanderthals, which was exclusively transferred from the mother to the children, it was calculated in 2009 that around 70,000 to 40,000 years ago, at most 3500 female Neanderthals lived at the same time. How meaningful this estimate is, however, remained controversial. On the one hand, it was derived from it that the total population at a certain point in time during this late phase of the Neanderthals was only 7000 individuals; At the same time, however, an accompanying article in the journal Science referred to model calculations for today's population in Sweden, where around nine million people live. However, a procedure comparable to that of the Neanderthals would only result in 100,000 individuals for today's Swedish Homo sapiens population; therefore the actual number of female Neanderthals in the mentioned epoch could well have been 70,000.

Jean-Jacques Hublin from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology , on the other hand, came to the conclusion in 2018 that "even at times of their greatest distribution" there were no more "than an estimated 10,000 'Neandertal Europeans'" at the same time, with the size of the individual groups comprised “a maximum of 50 to 60 women and men”.

die out

The reasons for the extinction of the Neanderthals are unknown. Archaeological evidence of acts of war between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans is just as little as evidence of a very rapid displacement of the Neanderthals by anatomically modern humans. On the contrary: in 2014 it was calculated that Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans coexisted in Europe for 2600 to 5400 years; In 2020, this period was narrowed down to 3960 ± 710 years after an updated calibration of the C14 method .

Numerous hypotheses have been put forward to explain the disappearance of the Neanderthals. In a review paper published in 2021, these hypotheses were grouped as follows:

- The cause of the extinction was competition for limited resources . Depending on the opinion of the individual researcher, the following characteristics of the anatomically modern human being are placed in the foreground for their superiority, viz

- morphological features

- cognitive traits

- technological features

- social characteristics

- economic features.

- The cause of the extinction was the internal demographic dynamics of Neanderthal populations:

- Even without competition from anatomically modern humans, the Neanderthal population was too small to survive in the long term.

- The small size of the local sub-populations and their insufficient networking with other sub-populations made the Neanderthals susceptible to inbreeding and led to inbreeding depression due to the missing Allee effect .

- The cause of the extinction were changes in the environment:

- the climate became more unstable (among other things, as part of the Heinrich event , known as H4, about 40,000 years ago).

- there were extreme climatic situations after the eruption of a volcano in the Phlegraean fields of the southern Italian region of Campania (cf. Campanian ignimbrite ).

- anatomically modern humans brought pathogens to which they were immune, but Neanderthals did not.

Some of these hypotheses have been challenged by recent research. For example, in 2012 a team of scientists published a study that found that the gradually colder climate in Europe 40,000 to 30,000 years ago did not appear to have had a significant impact on the Neanderthal extinction, since the main glaciation in Europe only began and peaked around 25,000 years ago 20,000 years ago, when the Neanderthals were long extinct. However, according to a 2018 study, between 44,000 and 40,000 years ago there were numerous alternations of pronounced cold phases and less cold interstadials . This repeatedly led to regional Neanderthal depopulation and subsequently - possibly - to colonization of the depopulated regions by Homo sapiens .

It is also suggested that Cro-Magnons benefited from hunting with early "wolf-hounds". However, in 2014, the US archaeologist Paola Villa and her Dutch colleague Wil Roebroeks did not find any archaeological findings in the entire specialist literature that would prove a cultural superiority of Homo sapiens over Neanderthals; instead they suspect a gradual numerical superiority of Homo sapiens . Model calculations show that group size and population density can have an impact on cultural complexity. The German paleoanthropologist Friedemann Schrenk also suspects: “The theory of Neanderthals as reproductive muffles appears most likely. So-called 'bottle-neck' situations, i.e. population bottlenecks, were not uncommon in human history and could therefore also have affected the Neanderthals.” A survey of more than 200 paleoanthropologists that became known in 2021 showed that the vast majority of researchers today population-biological disadvantages of the Neanderthals compared to the anatomically modern humans as the main reason for their extinction. The comparison of 17,367 protein-coding genes from Neanderthals from Spain, Croatia and southern Siberia - that is, from widely separated regions of Eurasia - indeed revealed evidence of "remarkably low" genetic diversity. The fact that anatomically modern humans became sexually mature earlier and had more descendants could also have been decisive for the extinction.

There is also archaeological evidence that, for example, in the Aquitaine region - an area with the greatest density of finds of both populations - the number of individuals of Homo sapiens increased tenfold between 55,000 and 35,000 years ago. Homo sapiens could probably survive better than the Neanderthals in densely populated areas due to their culturally transmitted behavior. Statistical population models show that differences in reproductive rates of just a few percent are enough to lead to the extinction of the less favored population in a few thousand years. In a review article in 2010, Katerina Harvati named not only a higher birth rate, shorter intervals between two births and the resulting larger groups, but also other scenarios that individual researchers - in different combinations - consider possible: For example, anatomically modern people could have a have had lower mortality, a wider diet, and better clothing or shelter during the cold periods. Different customs in the exchange of goods were also considered.

relationship to modern man

historical

After the view that the Neanderthals were a forerunner of the anatomically modern human being had gained acceptance at the end of the 19th century, a debate about their family closeness, which continues to this day, began in specialist circles. There were initially different opinions, particularly on the question of whether the Neanderthals were merely the temporal and spatial forerunners of Homo sapiens or whether the anatomically modern human developed from them. The German anatomist Gustav Schwalbe , for example, examined the Neanderthal finds known up to 1906 (he called them Homo primigenius , "primitive man") and interpreted some finds as "intermediate forms between Homo primigenius and sapiens." The prevailing opinion in the 1910s and 1920s was, however, mainly influenced by Arthur Keith and by Marcellin Boule , who had written the first scientific description of an almost complete Neanderthal skeleton; both were among the most influential paleoanthropologists of their era. In their opinion, the physique of the Neanderthals was so “ primitive ” that they could not be a direct ancestor of Homo sapiens . This view was partly due to an incorrect reconstruction of the Neanderthal find La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 by Marcellin Boule, who had reconstructed the fossil in a crooked posture, with a bent spine and bent legs.

This interpretation changed in the 1930s, when Ernst Mayr , George Gaylord Simpson , and Theodosius Dobzhansky associated the Neanderthals as Homo sapiens neanderthalensis with the anatomically modern humans of the same species, now called Homo sapiens sapiens . The seemingly complete sequence of sites of both - now - subspecies in Europe has been interpreted to mean that there was a slow, gradual evolutionary transition from Neanderthals to anatomically modern humans. For example, Aleš Hrdlička defended the hypothesis of the “Neanderthal phase of man” in 1927. In 1943, Franz Weidenreich again referred to the Neanderthals as an “intermediate form” between the Chinese Sinanthropus and Homo sapiens , so he also opted for a continuous transition, and as late as 1964 this view was defended by a large and prominent group of authors. Together with similar interpretations of finds in Asia, these considerations also led to the hypothesis of the multi-regional origin of modern humans .

In the four decades that followed, numerous newly discovered fossils and the subsequent reinterpretation of earlier finds in Europe ensured that the early, so-called Presapian fossils were all placed in the ancestral lineage of Neanderthals; these included the Swanscombe skull from England , the Steinheim skull in Baden-Württemberg , and the Tautavel and Biache-Saint-Vaast skulls in France. As early as 1973, William W. Howells certified the Neanderthals in his extensive study Cranial Variation in Man that the anatomical features of their skulls are outside the range of variation of Homo sapiens and they can therefore be attributed to a separate species. Furthermore, his data gave no indication that there was a gradual transition from Neanderthals to anatomically modern humans in Europe. By the early 1980s, the doctrine in paleoanthropology gradually gained acceptance that in Europe there was only the line of development leading to the Neanderthals and that there is a separate line of development - related to Homo sapiens - that of African fossils of the early Upper Pleistocene to the Cro-Magnon people of western Eurasia and to the people of the present day. This “Afro-European Sapiens Hypothesis” first formulated by Günter Bräuer at the 1st International Congress of Paleoanthropology in Nice is now known as the Out-of-Africa Theory . However, a small number of researchers continued to advocate the multiregional model, such as Milford H. Wolpoff and Alan G. Thorne - supported et al. to morphological analyzes by Weidenreich – as late as 2003, while researchers such as Günter Bräuer assumed that Homo sapiens replaced the Neanderthals in Europe and other archaic species such as Homo erectus in Asia (“replacement” instead of “continuity”), which they believed after but did not rule out the possibility of gene flow between species. The departure from the presumed gradual evolutionary transition from Neanderthals to anatomically modern humans resulted in both being re-established the status of species ( Homo neanderthalenis and Homo sapiens ) rather than subspecies. Chris Stringer justified this in 2001 and again in 2014, for example, with the fact that Neanderthals are closely related to Homo sapiens , but have a sufficient number of anatomical features unique to them. Ian Tattersall reinforced this argument from the perspective of the morphological species concept in 2015, while Fiorenzo Facchini (2006) and some other researchers continue to prefer a classification as a subspecies.

According to Svante Pääbo, it is unclear whether, given the genetic data, the classification of Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans into two biological species will endure, since there is no species definition "that applies to all groups of animals or hominids."

In summary, Chris Stringer had already stated in 2012: "Although the normal species definition is not given due to the incomplete reproductive delimitation, it is too early and, given the large morphological differences, not yet necessary for practical reasons, H. heidelbergensis , H. neanderthalensis and the Denisova- To group people with H. sapiens in one species.” The particularly large morphological differences include, for example, the shape of the faces and the brains of both species.

Today's Perspectives

The relationship between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans ( Homo sapiens ) is considered to be largely clarified. There is a consensus among paleoanthropologists that both shared a common ancestor in African Homo erectus . Based on fossil and tool finds, it is considered proven that Homo erectus left Africa "during the first wave of expansion about 2 million years ago" towards the Levant , Black Sea region and Georgia and possibly via Northwest Africa towards southern Spain. This early settlement of Georgia is evidenced by the 1.8 million year old hominin fossils from Dmanisi . The oldest, highly fragmented finds in Europe come from Spain. These 1.2 million year old finds are referred to by their discoverers as Homo antecessor and identified as the ancestors of Neanderthals; however, this interpretation is highly controversial and seems to have been refuted by recent genetic findings on the relationship between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans.

According to many paleoanthropologists, around 600,000 years ago a second wave of spread of African Homo erectus occurred . Skulls from that period found in Spain, for example, suggest a volume of between 1100 cm³ and 1450 cm³ for the brain; the brain volume of the fossil finds from the first wave of propagation, however, is estimated at just over 1000 cm³. After this second colonization of Europe by Homo erectus , this intermediate stage, known in Europe via Homo heidelbergensis , developed into the Neanderthal, while in Africa around 300,000 years ago - documented by fossil finds - Homo erectus became the so-called early anatomically modern human and from this today's human emerged.

What is more controversial, however, is when the lineage leading to Neanderthals separated from the lineage leading to modern humans. Based on the molecular clock , a time span between 440,000 and 270,000 years ago was initially calculated in 2010. However, the “accuracy” of the molecular clock on which such estimates are based is disputed; The dates determined with the help of geological - especially stratigraphic - methods often deviate considerably from those determined with the help of the molecular clock. In the case of the separation of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens , the dating of the Spanish finds mentioned, which are attributed to the second wave of expansion of Homo erectus , argued against the calculations using the molecular clock. A recalculation of the mutation rates in 2012 also revealed indications of a much earlier separation; it was - quite imprecisely - dated to between 800,000 and 400,000 years ago. The dating is supported, among other things, by the approximately 400,000-year -old Swanscombe skull , to which - although mostly still placed with Homo heidelbergensis - clear characteristics of the early Neanderthals were already ascribed.

Attempts at dating using the "molecular clock" also differ significantly from findings derived from the analysis of 1200 hominin molars , including teeth from all species of the genus Homo and from Paranthropus . A Spanish-American group of researchers used Neanderthal teeth and teeth from anatomically modern humans to reconstruct the teeth of the last common ancestor of both populations and compared this reconstruction with the teeth of early hominid species. In the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , they reported in 2013 that - derived, among other things, from the change in tooth shape in the transition period from Homo heidelbergensis to Neanderthals - according to their calculations, the development lines of Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans already diverged 1 million years ago parted In 2019, this argument was reinforced in another study and 800,000 years was calculated as the minimum age for the last common ancestor.