Peking man

As Peking Man are fossils indicated that from the 1920s in a cave ( "Lower cave" or Locality 1 ) near Zhoukoudian , about 40 km south-west of the center of Beijing , were discovered and the genus Homo are assigned. The ages of the fossil-containing layers of Locality 1 cover a range from around 780,000 to 400,000 years ago.

Naming

In 1927, the fossil finds, based mainly on a single tooth, were given the new species and genus name Sinanthropus pekinensis Black & Zdansky (“Chinese man from Beijing”) by Davidson Black . In 1940 the finds - based on meanwhile several dozen fossils - were interpreted by Wilfrid Le Gros Clark as closely related to the " Java people " from Java ( Indonesia ) and, like them, with the species and genus name Pithecanthropus erectus chosen by Eugène Dubois in 1892 ("Upright ape man") named; shortly before that, Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald and Franz Weidenreich had highlighted the anatomical similarities between the two finds. Since 1950, the fossils are of both sites by most paleoanthropologists as Homo interpreted to and the nature of Homo erectus ( "upright man") assigned, in particular, the origin of Chinese Finds sometimes by adding a subspecies - epithet is emphasized: Homo erectus pekinensis ( "Upright man from Beijing"). Occasionally, however, it is assumed that - according to the hypothesis of the multiregional origin of modern humans, largely independent of the development of the genus Homo in Africa - a variant of the archaic Homo sapiens developed from Homo erectus in Asia , so that the findings of Zhoukoudian then as Homo pekinensis ("man from Beijing").

According to Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald, the name Peking Man goes back to the German-American geologist Amadeus William Grabau , who was the first to speak of the Peking Man in 1927 .

Find history

The discoverers of the site were workers who mined limestone . Embedded in the rock, they often came across bones, which they interpreted as " dragon bones ", which is why the site was named dragon bone hill from them . Such "dragon bones" used in traditional Chinese medicine as medicaments and miracle cures had around 1900 a. a. The German paleontologist Max Schlosser bought it in Chinese pharmacies, which in turn a decade later prompted the Swedish geologist Johan Gunnar Andersson to search for fossils in the northern Chinese provinces of Henan and Gansu from 1914 to 1918 and, most recently, on the dragon bone mound. He recognized the limestone caves of Zhoukoudian as particularly suitable for systematic exploration, which is why he commissioned Otto Zdansky to organize excavation work there. Otto Zdansky had just completed his training at the University of Vienna and agreed with Andersson that instead of being paid for his work, he would be given the right to publish all finds in his own name. In 1921 the excavations began in the "lower cave" of the dragon bone mound , where an upper right hominine molar was discovered in the summer of 1921 . Only after Zdansky had returned to Sweden in 1926 did he notice the fragment of a second hominine tooth, a lower premolar, in the collection boxes that had been shipped from Beijing to Sweden . Now, for the first time, Zdansky informed his sponsor Andersson about these teeth, and one year later, in 1927, Zdansky reported in the journal Bulletin of the Geological Survey, China about these finds, which he cautiously ascribed to a species of the genus Homo that could not be identified .

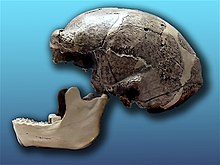

At the same time as Zdansky, some North American geologists were in Beijing to prepare a large expedition of the American Museum of Natural History to Mongolia . The deputy director and chief paleontologist of these scientists was Walter W. Granger , who was invited by Andersson to visit the excavations at Dragon Bone Hill. Davidson Black, who was then professor of anatomy at the Rockefeller Institute in Beijing, was also impressed by the excavations, especially after he had examined the two teeth. Thanks to the support of American colleagues, he was therefore able to acquire a generous grant from the Rockefeller Foundation for a Cenozoic Research Laboratory and to begin his own excavations on April 16, 1927, which led to the discovery of another lower molar on October 16. Based on this third tooth, Black defined the new genus and species Sinanthropus pekinensis in 1927 . The official directors of the excavations were initially the geologists Ding Wenjiang and Wong Wenhao . In the years up to 1937 - under the direction of Davidson Black, Pei Wenzhong and Jia Lanpo (one of the participants in the excavation was the Jesuit Teilhard de Chardin in 1929 ) - parts of 14 skulls, including complete ones, 14 lower jaws, more than 150 teeth and numerous other skeletal remains recovered; the finds represented more than 40 individuals of both sexes, about a third were children. After Davidson Black's untimely death in 1934, Franz Weidenreich continued the detailed scientific work on Zhoukoudian's finds, including making casts of all the fossils.

Above Locality 1 (= "Lower Cave") there is another paleoanthropological and archaeological site, the "Upper Cave". It was explored in 1933 and 1934, and found fossil bones of at least eight individuals of anatomically modern humans ( Homo sapiens ), including three relatively intact skulls of an older man, a middle-aged woman and a girl, as well as four lower jaws, dozen individual teeth and numerous more bones from the body below the head. The skulls were related to Europeans (the man), Eskimos (the girl) and Melanesians (the woman), but not to today's Chinese . A minimum age of 35,100 to 33,500 years was calculated for the finds.

Loss of fossils

The casts and the numerous drawings of the fossils that Franz Weidenreich made for his specialist publications are almost the only things that have survived from the finds from the Lower Cave . In July 1937, Beijing was occupied by Japanese troops as a result of the Second Sino-Japanese War . In December 1941, the military situation in the region came to a head, with fears that the Japanese could take control of the Peking Union Medical College (Běijīng Xiéhé Yīxuéyuàn), the repository of the Peking man's fossils. In order to protect the finds from access by the Japanese and to prevent their possible dispatch to Japan, all bones - with the exception of the teeth discovered by Zdansky, which had been stored in Uppsala ( Sweden ) - were individually and lavishly padded and packed in small wooden boxes these were made ready for travel in two transport boxes to be brought from Beijing to the USA . On December 5, 1941, the two shipping crates were taken to the port city of Qinhuangdao in a US Navy railroad car to be loaded onto the USS President Harrison . On December 7th, however, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor occurred , to which the USA responded with a declaration of war against Japan and the entry of the United States into World War II . This, in turn, had the consequence that the USS President Harrison was sunk by its crew and the US base Qinhuangdao surrendered. The military train that had the fossils on board was captured by the Japanese - the whereabouts of the two shipping crates is unknown and none of the fossils has ever been found again.

In the years 1951, 1955, 1966 and 1973, new excavations u. a. A piece of a tibia, a part of a lower jaw and some skull fragments were also found, five teeth, which are now kept in the Institute for Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, and a fragment of a humerus . In addition, there are the first two teeth, discovered by Otto Zdansky and preserved in Uppsala, also a third tooth, which Zdansky only recognized as hominin in 1952 in a renewed survey of his fossil collection, and finally a fourth canine tooth , also archived in Uppsala . Johan Gunnar Andersson sent this canine tooth with numerous other fossils from Beijing to Carl Wiman in Sweden in the mid-1920s and stored it there, but the 40 crates with fossils were only opened in 2011 to catalog their contents - and the hominine tooth was discovered.

Along with the fossils of the Peking people, the finds from the "Upper Cave" were also lost in December 1941.

Dating

The dating of the finds proved to be difficult because the bones had been recovered from horizons of different ages and younger rock from the broken-down cave ceiling had been laid over older sediments. Therefore, their age is given in the specialist literature partly as 420,000 years, partly as 600,000 years. In 2009, the aluminum-beryllium method was used to determine an age of 770,000 ± 80,000 years for the oldest layer in which skulls II, III and XIII had been discovered. A slightly younger age was calculated for skulls VI to XII, and an age of 400,000 to 500,000 years was calculated for skulls I and V, which came from two different, younger horizons. In any case, according to the dating, all individuals were contemporaries of European Homo heidelbergensis .

Special features and other finds

Based on 17,000 finds in the Zhoukoudian cave, it is certain that the Peking people made stone tools of the Oldowan type. However, it is controversial whether the blackening on some bones is due to fire; So far, no ash and therefore no direct evidence of a hearth fire has been found, but evidence of natural entry of ash by wind has been found. Certain damage to tubular bones and skulls, which was initially interpreted as a possible indication of cannibalism , is now interpreted partly as an expression of funeral rites, partly as damage by hyenas .

On the basis of casts of six original, particularly completely preserved skulls, a volume of 1058 cm³ was calculated in 2010, which corresponds to about two thirds of the inner space of today's humans. A reconstruction of an internal volume of the skull published in 2009 resulted in 1140 cm³.

The so-called Yuanmou man and the so-called Jianshi man as well as the 475,000 year old teeth from the Tham Khuyen cave (North Vietnam) on the border between Vietnam and China are also assigned to the Peking man . Their dates are mostly very well fitting, but the sometimes complex stratification of the find situation through cave collapse also resulted in much older age information.

According to a study published in 2011, the Beijing people differ so clearly from the older fossils known as Java people that both Homo erectus populations may have immigrated to Asia independently - in two separate waves - from Africa.

See also

literature

- Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald : Encounters with the pre-humans. dtv, Munich 1965, pp. 38-52

- Alan Walker and Pat Shipman: The Man Who Lost the Missing Link. Chapter 4 in: The Same: Turkana Boy. In search of the first person. Galila Verlag, Etsdorf am Kamp 2011, pp. 83-102, ISBN 978-3-902533-77-7 .

- Chen Shen, Xiaoling Zhang and Xing Gao: Zhoukoudian in transition: Research history, lithic technologies, and transformation of Chinese Palaeolithic archeology. In: Quaternary International. Volume 400, 2016, pp. 4-13, doi: 10.1016 / j.quaint.2015.10.001

- Noel T. Boaz et al .: Mapping and taphonomic analysis of the Homo erectus loci at Locality 1 Zhoukoudian, China. In: Journal of Human Evolution . Volume 46, No. 5, 2004, pp. 519–549, doi: 10.1016 / j.jhevol.2004.01.007 , full text (PDF) [a three-dimensional reconstruction of Locality 1 ]

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Bernard Wood : Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution. Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, p. 849, ISBN 978-1-4051-5510-6 .

- ^ A b Davidson Black : On a Lower Molar Hominid Tooth From the Chou Kou Tien Deposit. In: Paleontologia Sinica. Series D, volume. 7 Fascicle I, 1927

- ^ Wilfrid Le Gros Clark : The Relationship between Pithecanthropus and Sinanthropus. In: Nature . Volume 145, 1940, pp. 70-71, doi: 10.1038 / 145070a0

- ^ Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald and Franz Weidenreich : The Relationship between Pithecanthropus and Sinanthropus. In: Nature. Volume 144, 1939, pp. 926-929, doi: 10.1038 / 144926a0

- ↑ Valery Zeitoun et al .: Solo man in question: Convergent views to split Indonesian Homo erectus in two categories. In: Quaternary International. Volume 223–224, 2010, pp. 281–292, doi: 10.1016 / j.quaint.2010.01.018 , full text (PDF)

- ^ Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald: Encounters with the pre-humans. dtv, Munich 1965, p. 41.

- ↑ Lydia Pyne: Peking Man: A Curious Case of Paleo-Noir. Chapter 4 in: Dies .: Seven Skeletons. The Evolution of the World's Most Famous Human Fossils. Viking, New York 2016, pp. 122-125, ISBN 978-0-525-42985-2

- ↑ Djia Lan-Po: The home of the Peking man. Peking 1976, Verlag für Fremdsprachige Literatur, pages 1 and 11

- ↑ Vincent L. Morgan and Spencer G. Lucas: Walter Granger 1872-1941. Paleontologist. In: New Mexico Museum of Natural History, Bulletin. No. 19, 2002; Online excerpt (PDF)

- ↑ Otto Zdansky : Preliminary notice on two teeth of a hominid from a cave in Chihli (China). In: Bulletin of the Geological Survey, China. Volume 5, No. 3-4, 1927, pp. 281-284, doi: 10.1111 / j.1755-6724.1926.mp53-4007.x .

- ^ The Granger Papers Project.

- ^ Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald, Encounters with the Vormenschen , pp. 40–42

- ↑ Friedemann Schrenk : The early days of man. The way to Homo sapiens. CH Beck, Munich 1997, p. 83

- ^ Franz Weidenreich: The Skull of Sinanthropus pekinensis. A Comparative Study on a Primitive Hominid Skull. In: Palaeontologica Sinica. New Series D., No. 10. Whole Series No. 127, 1943 (PDF) Comprehensive illustrated review article, archived in the Internet Archive .

- ↑ Feng Li, Christopher J. Bae, Christopher B. Ramsey, Fuyou Chen and Xing Gao: Re-dating Zhoukoudian Upper Cave, northern China and its regional significance. In: Journal of Human Evolution. Volume 121, 2018, pp. 170–177, doi: 10.1016 / j.jhevol.2018.02.011

- ↑ You are now in the American Museum of Natural History in New York

- ↑ Lydia Pyne, Peking Man: A Curious Case of Paleo-Noir , pp. 136-138

- ^ Archeology: Peking Man, still missing and missed. On: nytimes.com October 11, 2005

- ↑ Gary J. Sawyer, Viktor Deak: The Long Way to Man. Life pictures from 7 million years of evolution . Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg 2008, p. 129

- ^ Song Xing et al .: Morphology and structure of Homo erectus humeri from Zhoukoudian, Locality 1. In: PeerJ. 6: e4279, January 2018, doi: 10.7717 / peerj.4279

- ↑ Otto Zdansky: A New Tooth of Sinanthropus pekinensis Black. In: Acta Zoologica. Volume 33, No. 1-2, 1952, pp. 189-191, doi: 10.1111 / j.1463-6395.1952.tb00363.x

- ↑ Clément Zanolli et al .: Inner tooth morphology of Homo erectus from Zhoukoudian. New evidence from an old collection housed at Uppsala University, Sweden. In: Journal of Human Evolution . Volume 116, 2018, pp. 1–13, doi: 10.1016 / j.jhevol.2017.11.002

- ^ A new tooth of Peking Man. On: evolutionsmuseet.uu.se from March 2011

- ^ Martin Kundrat et al .: New Tooth of Peking Man Recognized in Laboratory at Uppsala University. In: Acta Anthropologica Sinica. Volume 34, No. 1, 2015, pp. 131–136, doi: 10.16359 / j.cnki.cn11-1963 / q.2015.0015 , full text (PDF), Chinese and English

- ↑ Guanjun Shen, Xing Gao, Bin Gao and Darryl E. Granger: Age of Zhoukoudian Homo erectus determined with 26Al / 10Be burial dating. In: Nature . Volume 458, 2009, pp. 198-200; doi: 10.1038 / nature07741 , full text

- ↑ G. Shen and L. Jin: Restudy of the upper age limit of Beijing man site. In: International Journal of Anthropology. Volume 8, No. 2, 1993, pp. 95-98, doi: 10.1007 / BF02447617

- ^ Rex Dalton: Peking Man older than thought. On: nature.com from March 11, 2009, doi: 10.1038 / news.2009.149

- ^ Paul Goldberg, Steve Weiner, Ofer Bar-Yosef , Q. Xud and J. Liu: Site formation processes at Zhoukoudian, China. In: Journal of Human Evolution. Volume 41, No. 5, 2001, pp. 483-530, doi: 10.1006 / jhev.2001.0498

- ↑ Friedemann Schrenk: The early days of people , p. 83 f.

- ^ Gary J. Sawyer, Viktor Deak: The Long Way to Man , p. 126

- ↑ Xiujie Wu, Lynne A. Schepartz and Christopher J. Norton: Morphological and morphometric analysis of variation in the Zhoukoudian Homo erectus brain endocasts. In: Quaternary International. Volume 211, 2010, pp. 4–13, doi: 10.1016 / j.quaint.2009.07.002 , full text (PDF)

- ↑ Xiujie Wu, Lynne A. Schepartz and Wu Liu: A new Homo erectus (Zhoukoudian V) brain endocast from China. In: Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Online publication of April 29, 2009, doi: 10.1098 / rspb.2009.0149

- ^ Russell Ciochon et al .: Dated co-occurrence of Homo erectus and Gigantopithecus from Tham Khuyen Cave, Vietnam. In: PNAS . Tape. 93, 1996, pp. 3016–3020, full text (PDF)

- ↑ Yahdi Zaim et al .: New 1.5 million-year-old Homo erectus maxilla from Sangiran (Central Java, Indonesia). In: Journal of Human Evolution. Volume 61, No. 4, 2011, pp. 363-376, doi: 10.1016 / j.jhevol.2011.04.009