Klausenhöhle

| Klausenhöhle

|

||

|---|---|---|

|

Entrance to the Klausen cave |

||

| Location: | Essing in the Altmühltal | |

| Height : | 398 m above sea level NN | |

|

Geographic location: |

48 ° 56 '4.8 " N , 11 ° 47' 4.4" E | |

|

|

||

| Cadastral number: | I 9 (ae) | |

| Overall length: | 330 m | |

The Klausenhöhle is a natural karst cave near the Lower Bavarian market town of Essing in the Kelheim district in Bavaria .

description

It is a publicly accessible cave in the Altmühltal . The approx. 330 meter long cave in the Jura limestone is located between 25 and 55 meters above the valley floor. The cave consists of several rock niches lying close together at four different altitudes. As archaeological sites , they are divided (from bottom to top) into the Lower Klause, the Klausenniche and the Middle and Upper Klause. There is a connecting passage from the Middle to the Upper Klause, the so-called chimney. The Klausen caves are designated as a valuable geotope (geotope number: 273H003) by the Bavarian State Office for the Environment .

Research history

From 1900 to 1908 the local researcher Joseph Fraunholz dug in the caves. He was a full-time rent agent , but had made a great contribution to researching many sites in the Naab and Altmühltal valleys. Between 1905 and 1908 he created a stratigraphy in niche B of the upper hermitage, which reached from the Moustérien to historical times. When the Wiedemann brewery from Neuessing carried out further excavations in the cave system in 1908 to build a "grotto tavern" in the Upper Klause , Ferdinand Birkner, who was a private lecturer in Munich at the time, was present. Layers of the late Worm Ice Age ( Magdalenian ) as well as shards and bones from the upper Holocene layers were recognized by him.

The prehistorian Hugo Obermaier (Institut de Paléontologie Humaine, Paris) from Regensburg suggested further excavations in 1912 and 1913, in which Ferdinand Birkner, Joseph Fraunholz, Gero von Merhart and Paul Wernert were also involved.

Further investigations in and in front of the Untere Klause and in the Middle Klause took place in 1960 and 1961 by the Institute for Prehistory and Protohistory at the University of Erlangen .

Lower hermitage

The Lower Klause was cleared out to a small amount of sediment around 1860 and turned into a beer cellar. Sintered strips on the walls mark the original sediment height. During subsequent excavations by the Erlangen Institute for Prehistory and Protohistory in 1960, no archaeological finds were made. Only at the cave forecourt were two layers still to be found, whereby stone tools from the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic were found mixed at the border between the two layers. The most significant pieces were preserved along the rock face in karst pockets.

In 1962, a collector found a strongly S-shaped curved collarbone fragment in one of the rock niches , for which Thomas Rathgeber assigned the abbreviation "Neuessing 3" and which may be ascribed to a Neanderthal man .

Niche

Which now 4.70 meters wide and 2.70 meters high to Abri beer garden was set 1860th A large part of the layers found was lost. Only small residues of the two upper layers could be examined. They contained finds from the Neolithic Age (layer 1) and a phase of the Upper Palaeolithic (layer 2) that can no longer be dated . Below a narrow Moustérien horizon (layer 3) followed a gray-yellow clay with numerous artefacts, animal bones and fireplaces, which Ferdinand Birkner initially placed in the Acheuléen and referred to as " Klaus niche culture " (layer 4). An empty red clay completes the sequence of layers at the bottom.

In the main find layer - gray-yellow clay layer 4 - during the excavations in the autumn of 1912 and 1913, various micoque wedges were found (at that time still called Acheuléen wedges), as well as hand axes , many hand ax blades , wedge knives , a few blade tips and various scrapers , many of which were made from Plate silex are made. This complex was of Gerhard Bosinski by the numerous wedge knife the Micoquian assigned "type Klaus niche" and in an early phase of the Würm provided. The animal world of the find layer is cold ages. B. woolly mammoth , woolly rhinoceros and wild horse .

A human tooth - according to the excavation report from deposits of the Riss-Würm intergazial - was identified by Wolfgang Abel in 1936 as the first right upper deciduous incisor of a Neanderthal child . The tooth is only fragmentary, the root is missing. It was found in the immediate vicinity of “Acheuléen blade tips”, which in the terminology of the time can stand for slender hand axes, hand ax blades or wedge knives. The tooth (abbreviation: Neuessing 1) is on the one hand referred to as "lost since the war", on the other hand it was listed by Erhard Schoch in his collection as early as the 1960s. This statement is confirmed by an x-ray of the tooth, which was only shown by Schoch ; the whereabouts of the fossil after the private collection was dissolved is still unclear.

Middle hermitage

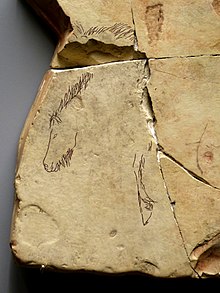

The Mittlere Klause is a 21 meter long and 18 meter wide, low hall, the walls of which are divided by several niches. The cultural sequence has been handed down from the excavations by Fraunholz and the Institut de Paléontologie Humaine, whereby it should not be ignored that the layers were largely mixed. In the top layer were finds from the Neolithic Age. This is followed by a gray-brown clay with a perhaps two-phase Magdalenian . In addition to the usual flint industry, the find complex contains a single-row harpoon , bone points with a double-beveled base, a needle, engraved ivory plates and lime plates with traces of red paint as well as a lime plate with the engraving of a horse and a sculpted hole stick with a bison head on the face.

The beautifully crafted leaf tips from the cave were originally placed in the Solutréen . According to current knowledge, however, these are leaf tips from the late Middle Paleolithic . The Middle Paleolithic is still represented with notched and serrated pieces, a few scrapers and hand axes.

Some of the finds, including a stem tip , come from the Gravettian , which was confirmed by radiocarbon dating of a worked bone from the upper hermitage to 24,680 ± 360 BP.

Upper Paleolithic burial

On October 4, 1913, during the excavations, Obermaier, Wernert and Birkner came across a grave pit in the middle of the cave, which was about 20 cm deep intrusively sunk into the older moustéry layer. A relatively complete male skeleton of an anatomically modern human ( Cro-Magnon human ) was found embedded in a dense red chalk pack , which is listed in the fossil catalog as "Neuessing 2". The handwritten protocol of the discovery is signed by Obermaier, Wernert and Birkner, the only publication on the circumstances of the find was made by Birkner. According to this, the dead was more than 50 cm below the level of the cave floor at the time of the excavation. A crevice was chosen for the laying down. The upper 30 cm of the overlying layers contained Neolithic find material, the 20 cm underneath an "unspoiled Magdalenian" with "Moustérien impact" (quotations from the protocol). A 60–70 cm thick layer of reddish-brown clay with individual Middle Paleolithic finds followed in the lying area. Later information on the layer thicknesses are partly different. The excavators rated the Magdalenian layer as an ante quem term to burial, as the grave surface had already been slightly torn up by the “Madeleine people” at that time. The distal end of the ulna was torn upwards and dyed gray to match the Magdalenian layer.

Using radiocarbon dating on a vertebral bone, the age of the grave was determined to be 18,590 ± 260 BP ( 14 C years) (Laboratory No. OxA-9856 ). This corresponds (after CalPal online) a calibrated age of 20,269 ± 439 v. It dates before the beginning of the Magdalenian era in Central Europe and is at the same time the oldest burial in Germany and the earliest fossil record of anatomically modern humans in Bavaria. The man, who was around 30–40 years old at the time of death, was buried in a stretched supine position facing south-north, from the basin downwards. The trunk with the head to the south was turned on its left side, so that the "line of sight" of the skull pointed to the west. The left arm was placed against the body, while the right forearm was bent over the pelvis.

The burial was wrapped in a mighty red chalk wrap , which was known as a typical burial custom in the Upper Paleolithic. Breaks of tusk teeth from the mammoth , caked in breccia-like fashion , were found under and above the skull , while the upper body lay on an irregular stone packing. The stones under the torso had been deposited there naturally, they were not placed by humans. The sediment of the grave pit was found free. It is assumed that this is the lower part of the excavation from the crevice filling. There were no additions directly related to the burial, even if Ferdinand Birkner associated a tip that had been retouched on both surfaces with the burial. A bone artifact ("smoother") from the rib of a hoofed animal was only recognized during a later inspection and was assigned to burial. The larger of the two fragments shows traces of red chalk from the grave pit.

As a result of several defects in the joint areas, the anthropologist Wilhelm Gieseler initially aimed at an interpretation as cannibalism , since he assumed that the bones were deliberately broken to remove the bone marrow. This contradicts a new analysis that could not determine any effects from tool use. Therefore, the assumption that it was a secondary burial can be ruled out according to the new investigations. The discovery protocol also referred to damage caused by lithographic printing and a partially selective recovery of the skeletal remains, for example in the area of the chest. The lack of skeletal elements is therefore apparently due to salvage-related causes and is not the result of a reburial at the time of the Upper Palaeolithic.

The human occupation of Central Europe was at the stage shortly after the Second Glacial Maximum of the last ice age ( Engl. LGM = Last Glacial Maximum) very thin. Among the few contemporaneous find sites include Wiesbaden -Igstadt and Grubgraben in chambers (Lower Austria).

Upper hermitage

The 27 meter long, 15.5 meter wide and up to 5 meter high hall is one of the most impressive cave rooms in the Altmühlalb. From layers of the Upper Magdalenian there are single-row harpoons, various bone points, three perforated rods, needles, various ivory objects, stone tools and pierced animal teeth. In addition, several limestone plates decorated with rows of red dots were found, which is a typical decorative element of the late Magdalenian period . There are comparable finds in southern Germany from the Hohlen Felsen near Schelklingen and from the “Kleine Scheuer”, the middle half-cave of the Hohlenstein . There are large numbers of such red-dotted stones in Birseck (Switzerland) and Mas d'Azil (southern France).

A mammoth tusk fragment with an incised drawing of a mammoth probably also belongs to the Magdalenian. The Moustérien the lower layer with various scrapers ordered Gerhard Bosinski his "Inventory type Kart stone to".

See also

- List of caves in Germany

- Schulerloch - visitor cave on the other side of the Altmühltal

literature

- Brigitte Kaulich: The Klausen cave. In: Rolf KF Meyer, Hermann Schmidt-Kaler: Walks into the history of the earth 6: Lower Altmühltal and Weltenburger Enge. Pfeil, Munich 1994, pp. 81-86.

- Michael Rind , Ruth Sandner: Klausenhöhlen - protection for Paleolithic hunters and gatherers. In: Altmühltal Archaeological Park: A travel guide to prehistoric times. Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7954-2106-9 , pp. 61-67.

- Mikeska, Detlef, Trappe, Martin, Miedaner, Helmut: The Klausen caves near Essing. In: Karst und Höhle 2008–2010. Southern Franconian Alb - Altmühl and Danube Valley region. Munich 2010.

- Martin Trappe: Geology in the area of the Klausen caves. In: Report on the 9th supra-regional surveying weekend in the Lower Altmühltal, 5th – 6th July 2004 , IHF / FHKF. Ingolstadt, 2003. pp. 95-96.

- Christian Züchner: The Klausenhöhlen near Neuessing. District of Kelheim. In: Hugo Obermaier-Gesellschaft (ed.): 50th annual conference in Erlangen. PrintCom, Erlangen 2008, ISBN 978-3-937852-02-7 .

Web links

- Text and photo collection about the Klausenhöhlen

- Klausenhöhle at caveseekers.com

- Klausenhöhle at caveclimbers.de (with sketch)

- 360 ° panorama of the upper hermitage (Flashplayer required)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bavarian State Office for the Environment, Klausenhöhlen W von Neuessing (accessed on October 6, 2017.)

- ↑ Stone Age dwellings near Neuessing in the Altmühltal. In: The Upper Palatinate 2 (12). Kallmünz, 1908, pp. 198-199.

- ^ Report: Yearbook of the Royal Bavarian Academy of Sciences. KB Academy of Sciences publisher in commission of G. Franz'schen Verlag, Munich 1915.

- ^ Lothar Zotz : Research by the Institute for Prehistory at the University of Erlangen in the Altmühltal. In: Prehistoric Journal 39, 1961, pp. 266-273

- ↑ a b Gisela Freund : On the question of palaeolithic settlement of the Lower Klause near Neu-Essing, Kelheim district. In: Germania 39, 1961, pp. 1-7.

- ↑ Thomas Rathgeber: Fossil human remains from the Sesselfelsgrotte in the lower Altmühltal (Bavaria, Germany). In: Quartär, Volume 53/54, 2006, pp. 33–59, here specifically text and footnote 2 on p. 36.

- ↑ Ferdinand Birkner: Ancient and Prehistory of Bavaria. Publisher Knorr & Hirth, Munich, 1936

- ↑ Gerhard Bosinski: The Middle Paleolithic finds in western Central Europe. Dissertation University of Cologne 1963. Böhlau, Cologne / Graz 1967.

- ↑ Wolfgang Abel: A human milk incisor from the Klausenhöhle (Ndb.) - With a find report by H. Obermaier. In: Journal for Ethnology , Volume 68, 1936, pp. 256-259.

- ^ Hugo Obermaier, Paul Wernert: Die Klausennische bei Neu-Essing (Niederbayern. Chapter in: Paläolithbeitbeitionen aus Nordbayern. Mitteilungen der Anthropologische Gesellschaft in Wien, Volume 44, 1914, pp. 53–55

- ^ A b W. Gieseler: Germany. In: Kenneth P. Oakley (ed.) (Inter alia): Catalog of Fossil Hominids: Europe. Part 2. Smithsonian Institution Proceedings, 1971, pp. 189-215.

- ↑ Hansjürgen Müller-Beck : The upper Old Palaeolithic in southern Germany. Part 1 (text), Habelt in Commission, Bonn 1957, p. 38

- ↑ Erhard Otto Schoch: Fossil human remains. The way to Homo sapiens (= The new Brehm library. Volume 450). Wittenberg, Ziemsen-Verlag, 1973, (2nd edition, 1974), pp. 88-89.

- ^ A b Hugo Obermaier, Josef Fraunholz: The sculpted reindeer antler stick from the Middle Klausen cave near Essing. In: IPEK 4, 1927, pp. 1-9.

- ↑ a b C. Sebastian Sommer (Ed.): Archeology in Bavaria - Window to the Past. Pustet, Regensburg 2006, ISBN 3-7917-2002-3 , p. 42f.

- ↑ a b c Ferdinand Birkner: The Ice Age settlement of the Schulerloch and the lower Altmühltal. Treatises of the Royal Bavarian Academy of Sciences, Mathematical-Physical Class, Volume XXVIII, 5th Treatise, Munich 1916, pp. 35-38

- ^ Martin Street, Thomas Terberger, Jörg Orschiedt : A critical review of the German Paleolithic hominin record. Journal of Human Evolution, Volume 51 (6), 2006, pp. 551-579, doi : 10.1016 / j.jhevol.2006.04.014 ; Full text p. 71. ( Memento from February 23, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF)

- ↑ CalPal website online (accessed February 14, 2014)

- ↑ a b Jörg Orschiedt: Middle Klause, Neuessing, Kr. Kelheim, Bavaria. In: Manipulation of human skeletal remains. Taphonomic processes, secondary burials or cannibalism? Urgeschichtliche Materialhefte 13, 1999, Tübingen, pp. 119–123.

- ↑ Peter Schröter: A bone artifact in the Upper Palaeolithic skeleton find from the Middle Klause near Neuessing, Gde. Essing, Lkr. Kelheim (Lower Bavaria). In: Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt 9, 1979, pp. 155–158

- ^ Wilhelm Gieseler: The Upper Palaeolithic skeleton from Neuessing. An example of cannibalism and subsequent burial. From home 61, pp. 161–174.

- ^ Wilhelm Gieseler: The Upper Palaeolithic skeleton from Neuessing. In: P. Schröter (Ed.), Festschr. 75 years of the State Anthropological Collection in Munich. Munich, 1977, pp. 39-51.

- ^ Martin Street, Thomas Terberger: The last Pleniglacial and the human settlement of Central Europe. New information from the Rhineland site Wiesbaden-Igstadt. Antiquity 73, 1999, pp. 259-272.

- ↑ Martin Street, Thomas Terberger: Upper Palaeolithic human remains in western Central Europe and their context. In: Dietrich Mania, Jan Michal Burdukiewicz (ed.): Knowledge hunters : Culture and environment of early humans. Publications of the State Office for Archeology Saxony-Anhalt - State Museum for Prehistory 57 (1 & 2), Halle 2003, ISBN 3-910010-69-5 , pp. 579–591.