Berlin-Charlottenburg

|

Charlottenburg district of Berlin |

|

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 52 ° 31 '0 " N , 13 ° 18' 0" E |

| surface | 10.6 km² |

| Residents | 130,663 (Dec. 31, 2019) |

| Population density | 12,327 inhabitants / km² |

| Incorporation | 1920 |

| Postcodes | 10585, 10587, 10589, 10623, 10625, 10627, 10629, 14052, 14055, 14057, 14059 |

| District number | 0401 |

| Administrative district | Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf |

Charlottenburg is a part of the Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf district of Berlin .

Founded as a city in 1705, Charlottenburg became a major city in 1893 . When it was incorporated into Greater Berlin in 1920 , it became the independent district of Charlottenburg . Before that, Charlottenburg was at times the municipality with the highest tax revenue per capita in Germany . After the merger with the then Wilmersdorf district to form the new Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf district during the administrative reform in 2001, the Charlottenburg district was downgraded to a district.

The districts of the Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf district were reorganized in 2004, as a result of which the area of the former Charlottenburg district was divided into the current districts of Westend , Charlottenburg-Nord and Charlottenburg.

Limits

Charlottenburg is limited

- west through the Ringbahn (this is where Westend borders),

- north through the Spree to Jungfernheide station , from there in an easterly direction through the S-Bahn-Ring (this is where Charlottenburg-Nord borders),

- east first largely through the Charlottenburg connecting canal and then through the Spree to Siegmunds Hof (here Moabit and the Hansaviertel border), then zigzag along the Zoological Garden to Olof-Palme-Platz (here borders the Tiergarten ),

- southeast through Nürnberger Straße ( Schöneberg borders here ),

- south through the course Eislebener Straße - Rankestraße - Lietzenburger Straße - Olivaer Platz - Kurfürstendamm to Lehniner Platz (this is where Wilmersdorf borders), then Damaschkestraße - Holtzendorffstraße - S-Bahn -track of the Wetzlarer Bahn to the Westkreuz station (where Halensee borders).

Today's district of Charlottenburg is located in Berlin's glacial valley , while parts of the Westend district to the west (until September 2004 to Charlottenburg) are located on the Teltow plateau (landscape) .

Residents

The district of Charlottenburg has 130,663 inhabitants, making it the most populous in the Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf district.

The disproportionate accumulation of Russian residents - especially after the First World War - led to the nickname Charlottengrad .

history

Early settlements

At the end of the Middle Ages , three settlements have been identified on Charlottenburger Grund: the Lietzow , Casow and a settlement called Glienicke . Although all three names are of Slavic origin, a mixed Slavic- German settlement can be assumed for this time .

Lietzow (also called Lietze , Lutze , Lutzen , Lützow , Lusze , Lütze and Lucene ) was first mentioned in a document in 1239. It was located in the area of today's Alt-Lietzow street behind the Charlottenburg town hall , Casow was opposite on the other side of the Spree in the area of today's Kalowswerder. In 1315 Lietzow and Casow were awarded to the St. Marien nunnery in Spandau . The large Lietzow farm may have been expanded into a village. In the course of the Reformation , the nunnery was closed. While the area of Lietzow was continuously settled to this day, Casow, as well as the third settlement Glienicke, was abandoned at some point. Based on old field names , Glienicke is suspected to be in the area now enclosed by Kantstrasse , Fasanenstrasse , Kurfürstendamm and Uhlandstrasse , located on a now silted lake, the Glienicker See.

Lietzow's development is well documented. For more than 400 years the Berendt family held the village school administration office and had to pay lower taxes to compensate for this activity. Lietzow was also cared for by the Wilmersdorfer pastor, who commuted between Wilmersdorf and Lietzow on the then Priesterweg , today the axis Leibnizstraße - Konstanzer Straße - Brandenburgische Straße.

Residential city

Sophie Charlotte received the place Lietzow and the Vorwerk Ruhleben in 1695 from her husband, Elector Friedrich III. transferred by Brandenburg in exchange for their more remote goods in Caputh and Langerwisch . There she had the summer palace Lützenburg built, which was completed in 1699. After the coronation of Sophie Charlotte as queen and Friedrich I as king in Prussia in 1701, the small pleasure palace was expanded into a representative palace by various architects by 1740. Shortly after the death of Sophie Charlotte, the settlement opposite Lützenburg Palace was given the name Charlottenburg by Friedrich I on April 5, 1705, and at the same time received city rights . Lützenburg Palace was also renamed Charlottenburg Palace . Until 1720 the king was also mayor of the city. In the same year the village of Lietzow was incorporated into Charlottenburg. With that, the city of Charlottenburg had reached the extent that it was to keep until the mid-1850s, today's old town Charlottenburg .

Friedrich's successor Friedrich Wilhelm I , known as the soldier king, stayed only rarely in Charlottenburg Palace, which had a negative effect on the development of the still very small royal seat. He even tried - unsuccessfully - to revoke Charlottenburg's city rights. It was not until his successor Frederick the Great took office in 1740, who at least regularly held court parties in the palace, that the city of Charlottenburg also moved more into the limelight. During his reign, however, he preferred the Sanssouci Palace near Potsdam , which he had planned in part, as a summer residence. However, when his nephew Friedrich Wilhelm II took over government after his death in 1786 , Charlottenburg Palace became his preferred residence. As early as 1777, Friedrich Wilhelm had given his lover and perhaps only confidante Wilhelmine Enke , who later became Countess von Lichtenau, a property with a large park in the triangle between Berliner Strasse (now: Otto-Suhr-Allee ), Spreestrasse (now: Wintersteinstrasse) and the Spree . The area was directly connected to the castle park. His son and successor Friedrich Wilhelm III. chose Charlottenburg Palace as his favorite residence. He and his family frequented the still small town of Charlottenburg and communicated with the local population as a matter of course.

After the defeat of Prussia in the battle of Jena and Auerstedt in 1806, Charlottenburg was occupied by the French for two years . Napoleon himself resided in Charlottenburg Palace, while his troops built a large army camp on the other side of today's Ringbahn in the area of Königin-Elisabeth-Straße.

Summer retreat

It was not only the personal preferences of the regents that encouraged the development of Charlottenburg in the late 18th century. The small town built on less fertile land was also discovered as a local recreation area for the up-and-coming city of Berlin. After the first real inn on Berliner Straße (today: Otto-Suhr-Allee ) opened in the 1770s , many other restaurants and beer gardens followed, which were particularly popular on weekends.

"During the summer, the city is inhabited by many Berliners who have tasteful country houses and gardens here, [...] Charlottenburg is the favorite spot for Berliners and is regularly visited by several thousands on Sundays."

Until the beginning of the 20th century, Charlottenburg remained an excursion area and summer retreat for Berliners. Those who did not come across the Spree by ship could be driven from the Brandenburg Gate to Charlottenburg and back: initially with so-called “gate wagons”, uncomfortable and irregularly traveling open vehicles. From 1825 they were juxtaposed with the rain-protected covered wagons of the haulage contractor Simon Kremser , which operated for a slightly higher fee at regular departure times. Such vehicles are still known today under the name of Kremser . The first horse tram in Germany has been running from the Brandenburg Gate to Charlottenburg since 1865 . The Westend villa colony was founded west of Charlottenburg in 1866 . The grounds of the palace of Countess Lichtenau were acquired by the Lichterfeld property speculator J. A. W. Carstenn in 1869 in order to build a large-format amusement park with a palm house, the " Flora ". The "Flora" only existed for a short time. To the amusement of the public, a so-called “ people show ” of an “ Ashanti caravan” for the year 1887 is documented. After the bankruptcy , the amusement facility was blown up in 1904 and the site was divided into 54 construction sites. This is how Eosanderstrasse and Lohmeyerstrasse came into being.

Bourgeois city

The increasing attractiveness attracted more and more wealthy Berlin citizens, who preferred to settle on the representative road connecting the palace and Berlin. For example, Werner Siemens had a villa built at Berliner Strasse 34–36 (today: Otto-Suhr-Allee 10–16) near the knee ( Ernst-Reuter-Platz ) in 1862 . From the 1870s onwards, important industrial companies such as Siemens & Halske and Schering also set up shop in the north-east of Charlottenburg. This started the city's rapid growth.

This growth was directed by the Hobrecht Plan , which gave the city of Berlin a certain structure to expand into the surrounding area. The generous honeycomb pattern of the planned streets was designed for the construction of tenements , from which James Hobrecht expected a social mix, with the upper bourgeoisie in the front building, the common people in the back buildings and side wings and small craft shops in the inner courtyards. This social mix actually took place, but Hobrecht had not foreseen that speculators would build up too densely on the land, so that life in the narrow, dark and damp backyards was very unhealthy. From this, social hot spots developed over time. In Charlottenburg, the Kiez south of Klausenerplatz should be mentioned in particular .

Against the background of the introduction of gas lighting , the Berlin police chief pushed for the construction of a separate gas works for Charlottenburg, which began operations in 1861 on the Charlottenburger Ufer (today Einsteinufer) of the Landwehr Canal; another at Gaußstr. ( Charlottenburg connection channel ) went online in 1891. So Charlottenburg came to street lighting very early. The existence of the old gas lanterns is now threatened.

After the city of Charlottenburg had more than 25,000 inhabitants in the 1875 census, it was hived off from the Teltow district on January 1, 1877 at its own request and made an independent urban district . At the same time, the mayor's office was taken over by Hans Fritsche , who managed to rehabilitate the city's finances. In Fritsche's tenure, which lasted until his death in 1898, there was a population explosion in which the population increased sevenfold. As a result, there was a constant lack of infrastructure : the school classes were overcrowded, the town hall soon became too small and the small hospital in Kirchstrasse (today: Gierkezeile) was constantly overcrowded despite the expansion. Even the churches were often unable to cope with the onslaught of believers. Since Charlottenburg had become a prosperous city after 1875, the city administration was able to fight the problems without solving them. At times, Charlottenburg was the city in Prussia with the highest tax revenue per capita.

Today's Technical University was built as a technical college from 1878 to 1884 . In 1893 Charlottenburg had more than 100,000 inhabitants for the first time and thus became a major city and at the same time, alongside Berlin, the largest city in the province of Brandenburg . The old town hall with its small-town layout had become much too small. The prestigious new town hall building, completed for the 200th anniversary in 1905, with the stately 88-meter-high tower that clearly towers above the dome of the castle, testifies to the increased self-confidence of the bourgeoisie. In 1900 the city built the Charlottenburg electricity works , also for reasons of demarcation from competing Berlin , which served to supply households and industry, the trams that were converted to electrical operation and, from 1905, street lighting. The world-famous Kaufhaus des Westens was opened in 1907 (due to a later change in the course of the border, the “KaDeWe” is now in the Schöneberg district ).

The 15th German Fire Brigade Day took place in Charlottenburg from July 9th to 13th, 1898 .

Around 1900 Charlottenburg was a city of great social contrasts in a small area. At the eastern end of Zillestrasse , for example, there were many simple workers and craftsmen - in some houses with no water connection - facing a few, particularly wealthy Charlottenburgers, who, like the Siemens and Warschauer families , were mostly just a few hundred meters away near today's Ernst-Reuter -Place lived. These not only ensured the city's high tax revenue, many also supported the city's social welfare with foundations. Some of the institutions financed by the foundations were built in the area of Westend, which has belonged to Charlottenburg since 1878 .

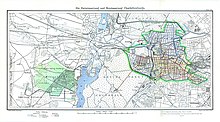

At the 1910 census, around 306,000 people were already living in Charlottenburg. The city was divided into 15 districts .

|

|

|

According to post districts, in the 1910s the properties of the streets were assigned to the Berlin post districts W 15, W 30, W 35, W 50, W 62, NW 87 and, for Charlottenburg, the post districts Charlottenburg 1 to Charlottenburg 5, Nonnendamm , Halensee, Plötzensee. On the other hand, roads extended beyond the Charlottenburg city limits to Schöneberger, Wilmersdorfer and Berlin areas from Charlottenburg.

In 1911 and 1912 the German Opera House was built on Bismarckstrasse . With the Greater Berlin Act passed in 1920, Charlottenburg was incorporated into the newly created Greater Berlin on October 1, 1920 and merged with the Plötzensee manor district and large parts of the Heerstraße and Jungfernheide manor districts to form the seventh district of Berlin and part of the " New West ".

District of Berlin

In order to counteract the mass unemployment that arose after the First World War , pre-war plans by the Charlottenburg City Garden Director Erwin Barth were taken up again, the Lietzenseepark was redesigned and the Jungfernheide laid out as a large public park. The rapidly developing automotive industry was interested in a car-only test track. For this purpose, the AVUS (Automobile Traffic and Practice Road) was created between Charlottenburg and Nikolassee . Construction began in 1913, due to the war , however, only completed the 1,921th

Exhibition halls were built at the zoological garden as early as 1905 to 1907, but they never really fulfilled their purpose. The auto industry in particular needed more spacious halls. The automobile exhibition hall at the north end of the AVUS was built for them in 1914. The Witzleben station was added to the ring line to provide transport links and opened in 1916. Due to the war, the first exhibitions in the automobile exhibition hall did not take place until 1919. This marked the beginning of today's exhibition center . Soon the one large exhibition hall was no longer enough. In 1924, a second automobile exhibition hall was built on the site of today's bus station. For the rapidly developing radio industry, a third exhibition hall south of the new automobile exhibition hall was built entirely of wood so as not to interfere with radio reception . At the same time, the construction of the Berlin radio tower began, which was completed in 1927. The wooden radio hall burned down in 1935, and the radio tower was also badly damaged.

time of the nationalsocialism

In the time of National Socialism , the focus was initially on hosting the 1936 Summer Olympics, which were awarded to Berlin in 1929 . The initially planned expansion of the German stadium , which was then located on Charlottenburger Grund, was stopped by Adolf Hitler in favor of a new building at the same location, from which greater representative and propagandistic effects were to be expected. The contract was awarded again to Werner March , son of Otto March , the architect of the German Stadium. The external appearance of the newly built Olympic Stadium was, however, strongly influenced by Hitler personally and his master builder Albert Speer . Numerous other facilities were built in this context: The first was the Germany Hall, completed in 1935 , in which the Olympic boxing competitions took place; then the Waldbühne (then named after Hitler's fatherly model Dietrich Eckart ) located on the Olympic site , which was then called the Reichssportfeld , as well as the bell tower with Langemarckhalle and the adjacent Maifeld as a parade ground.

After the Olympic Games around 1937, Hitler's plans to expand Berlin to become the “ world capital Germania ” began to take shape. Berlin was to be traversed by two imposing axes in north-south and east-west directions. The western axis cut through the Charlottenburg area coming from the Tiergarten on today's Straße des 17. Juni , Ernst-Reuter-Platz (formerly: Knie ), Bismarckstraße , Kaiserdamm , Theodor-Heuss-Platz , Heerstraße to the Stößenseebrücke . The area between the Brandenburg Gate and Theodor-Heuss-Platz was largely completed by 1939. The passage through the Charlottenburg Gate , which was only built at the beginning of the 20th century, had to be expanded. Since the western part along the Heerstraße was still largely undeveloped forest area, the area around it was ideal for further representative facilities. A clinic was planned between Westend and the Olympic site, south of Heerstraße the defense technology faculty, over the shell of which today the Teufelsberg heaped up from rubble from the Second World War lies, as well as a university town between the Olympic site and the Havel on both sides of Heerstraße. The high road station should be rebuilt as a prestigious reception station for state guests. The Theodor-Heuss-Platz (at that time: Adolf-Hitler-Platz ) was to be converted into a prestigious pageant with a Mussolini monument in the center. Apart from the shell of the defense technology faculty , which was completed at the beginning of the war , the projects only made rudiments beyond the planning phase.

With the Berlin regional reform on April 1, 1938, numerous straightening of the district boundaries and some major changes to the area were made. It came

- the area between Nollendorfplatz and Nürnberger Straße from the Charlottenburg district to the Schöneberg district

- the Eichkamp settlement from the Wilmersdorf district to the Charlottenburg district

- the western part of Ruhleben from the Charlottenburg district to the Spandau district

- the part of the Jungfernheide from the Charlottenburg district to the Reinickendorf and Wedding districts north of the Berlin-Spandau shipping canal

- the location Martinikenfelde from the Charlottenburg district to the Tiergarten district

City West

The Allied air raids particularly destroyed the eastern part of Charlottenburg. Contrary to initial plans and due to public protests, the ruins of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church were not torn down, but the tower of the church was left as a ruin. Berlin was divided into four sectors by the victorious powers of World War II and Charlottenburg was added to the British sector . As a result of the East-West confrontations that soon became apparent, the area around the Bahnhof Zoo , Breitscheidplatz and Kurfürstendamm soon developed into City West , the new center of West Berlin , as the historical center was in the Soviet sector . This tied in with old traditions from the Weimar Republic , in which the western center was known as the New West or the zoo district . From the mid-1950s, the abundant vacant lots were used to build high-rise buildings, initially around the newly designed knee , renamed Ernst-Reuter-Platz .

In 1961, the new building of the Deutsche Oper was opened in place of the smaller opera house destroyed in 1943 in World War II after the State Opera Unter den Linden in Mitte was de facto cut off from West Berlin by the construction of the Wall . From 1963, the Europa-Center was built on Breitscheidplatz as an office and commercial building in place of the Romanesque Café, which was also destroyed in World War II . The Europa-Center was to represent a landmark of the reconstruction and emphasize the affiliation of West Berlin to the Federal Republic and the western world by the analogy to the Kö-Center in Düsseldorf , which was built shortly afterwards, and the Bonn-Center in Bonn .

During the demonstration on June 2, 1967 in West Berlin against the visit of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi , the student Benno Ohnesorg was shot dead by the police officer Karl-Heinz Kurras near the Deutsche Oper for no apparent reason , which triggered the hot phase of the " '68 movement "was. At the Stuttgarter Platz , the settled community I and tried there new forms of life. The tabloids followed it with disgust and made it the talk of the day for months.

In the 1970s, new building activity subsided and more emphasis was placed on the renovation and maintenance of existing residential areas, with the backyard development typical of Berlin being thinned out in favor of a higher quality of living. The best example is the district around Klausenerplatz near Spandauer Damm , which was largely undamaged during World War II . At the “wet triangle” between Hebbel-, Fritsche- and Zillestrasse , the lowering of the groundwater level in connection with the construction of the U7 underground line created a risk of collapse for the residential area, which in 1972 had to be demolished at very short notice. In the building boom at the turn of the century, the possibilities for founding a silted lake were overestimated.

The area around Kantstrasse has been developing into a Chinatown or Asian Town in western Berlin for many years , with many Asian residents, shops, gastronomic and cultural offers. Over three percent of the population of Charlottenburg come from East Asia.

Since the 2010s, City West has again come into the focus of urban developers and investors. Examples of this are the 119-meter-high zoo window on Breitscheidplatz , which was completed in 2012 and which houses the luxury Waldorf Astoria Berlin hotel , and the neighboring - equally high - Upper West , which was completed in March 2017.

Also on Breitscheidplatz, the Bikini House with the Zoo Palast cinema was extensively renovated between 2010 and 2014 . Further extensive investments are planned in the vicinity.

The photo gallery C / O Berlin has opened its doors in the former America House since 2014 .

Locations and city quarters

Below the official structure, according to which the former district of Charlottenburg was divided into the three districts of Charlottenburg, Westend and Charlottenburg-Nord according to the decision of the district council meeting (BVV) of September 30, 2004, there are regional substructures of well-known localities and neighborhoods within the district of Charlottenburg:

Old town Charlottenburg

The old town of Charlottenburg emerged as a settlement from 1695 near the village of Lietzow , as a result of the palace construction, the former Lietzenburg Palace , which was built as a summer residence for the first Prussian Queen Sophie Charlotte of Hanover . After her death, the palace and location were renamed from Lietzenburg to Charlottenburg after her . Today's old town of Charlottenburg comprises the area between the Spree in the north, Nehringstrasse in the west and the axis Zillestrasse / Loschmidtstrasse in the south and east, which corresponds to the boundaries of the then independent city of Charlottenburg from 1720 to 1855, until the place grew beyond its borders . The old town of Charlottenburg was largely spared from destruction during the Second World War and has thus been able to maintain its small-town character to this day.

Alt-Lietzow

The real nucleus of the old Charlottenburg was the village of Lietzow , north of today's town hall . The area was probably inhabited since the Neolithic Age , it was first mentioned in 1239. As a result of the Second World War, hardly anything has been preserved from the original development of the place . The Alt-Lietzow street on the site of the former town center is reminiscent of the historic village. The shape of the former village can still be seen in the course of the road.

Klausenerplatz (Danckelmannkiez)

The residential area around Klausenerplatz , sometimes also called Danckelmannkiez , connects to the west of the old town of Charlottenburg. It emerged as a barracks district in the middle of the 19th century. Originally, the area around Klausenerplatz was considered a quarter for the “common people” or a typical “Zillekiez”, which earned it the nickname “Little Wedding ”. In fact, the Berlin Milljöhmaler Heinrich Zille lived and worked for many years in Sophie-Charlotten-Straße 88. Similar to the old town of Charlottenburg, the area remained largely undestroyed during World War II . A tenant initiative in 1973 prevented the area from being redeveloped, which essentially intended to break open the backyards typical of these Berlin areas. Today the Kiez is a rather quiet residential area between the industrial area Charlottenburg-Nord and City West .

Kalowswerder

Another residential area in the district is Kalowswerder , in the north of Charlottenburg, adjacent to the industrialized Charlottenburg-Nord . The term Kalowswerder is rarely used in common language today. More common is the reference to the centrally located Mierendorffplatz , so that mostly the Mierendorffkiez , and occasionally the Mierendorff Island, is mentioned.

Joke life

The community of Witzleben was established in 1820 as a country estate, named after Job von Witzleben , who had a park with a country house built here on a lake. The park still exists today as Lietzenseepark . At the turn of the 20th century, elegant apartment buildings for the upper classes of Berlin and Charlottenburg were built there. Today nothing can be seen of the former suburban atmosphere. After the Second World War , bomb holes were partly built with large apartment buildings and several large traffic arteries, such as Neue Kantstrasse and Kaiserdamm , criss- cross the local area. The name Witzleben is hardly used today and is rarely used by Berliners, only at the train station Messe Nord / ICC the historical name can still be read on old signs.

Embassies and diplomatic missions

- Republic of Ecuador

- Kyrgyz Republic

- Republic of Mali

- Kingdom of Nepal

- Republic of Paraguay

- Republic of the Philippines

- Military attaché of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Republic of Cyprus

Sights and culture

Museums

- Bröhan Museum for Art Nouveau , Art Deco and Functionalism

- Käthe Kollwitz Museum in Fasanenstrasse

- Ceramic Museum Berlin on the site of the oldest town house in Charlottenburg (built: 1712)

- Museum Berggruen in the western Stüler building on Schloßstraße , opposite on the central promenade of Schloßstraße is the Prince Albrecht monument

- Museum of Photography / Helmut Newton Foundation

- Scharf-Gerstenberg collection in the eastern Stüler building

- Charlottenburg Palace with palace gardens, Belvedere , new pavilion by Karl Friedrich Schinkel , orangery and mausoleum

Sacred buildings

Churches

- Catholic parish of St. Canisius

- Friedenskirche in Bismarckstrasse

- Gustav-Adolf-Kirche by Otto Bartning in Herschelstrasse

- Sacred Heart Church

- Evangelical Jonah Church

- Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church

- Catholic Church of St. Camillus

- Evangelical Church at Lietzensee

- Luisenkirche

- Mor Afrem Syriac Orthodox Church

- Francophone Catholic parish in the St. Thomas Aquinas Church

- Trinity Church

Synagogues

- Fasanenstrasse synagogue (destroyed during the November pogroms in 1938 , today the Jewish community hall , which, among other things, houses the Jewish adult education center)

- Liberal synagogue on Herbartstrasse in the former Leo Baeck retirement home

- Pestalozzistraße synagogue

- Central Orthodox Synagogue Berlin

Public buildings

- District Court of Charlottenburg

- Europacenter

- Kudamm-Karree high-rise

- Berlin Regional Court on Tegeler Weg

- Ludwig-Erhard-Haus of the IHK Berlin

- Charlottenburg Town Hall

- Technical University

- University of the Arts

- Registry office Villa Kogge

Cultural sites

- Astor Film Lounge on Kurfürstendamm

- Cinema Paris in the Maison de France on Kurfürstendamm

- C / O Berlin in the Amerikahaus

- Delphi Filmpalast at the Zoo in Kantstrasse

- Deutsche Oper Berlin in Bismarckstrasse

- The porcupines in the Europa Center

- Free theaters in Berlin on Klausenerplatz

- Jewish community center on Fasanenstrasse

- Kant cinema

- Comedy on Kurfürstendamm

- Literaturhaus Berlin in Fasanenstrasse

- New Berlin Scala , music theater

- Quasimodo on Kantstrasse

- Renaissance theater in Hardenbergstrasse

- Schiller Theater in Bismarckstrasse

- Theater on Kurfürstendamm

- Theater des Westens in Kantstrasse

- Grandstand in Otto-Suhr-Allee (currently no games)

- Vagant stage on Kantstrasse

- Zoo palace

Streets and squares

traffic

The first long-distance station was the Charlottenburg station on Stuttgarter Platz as the western terminus of the Berlin light rail . It was put into operation on February 7, 1882, the connection to the Wetzlarer Bahn , which had already reached Grunewald station in 1879 , on June 1, 1882.

The Zoologischer Garten station was also opened on February 7, 1882, but long-distance trains did not stop there until 1884. At the time of the Berlin Wall , it was a symbol of the connection with West Berlin for decades - just like the Tegel and Tempelhof airports of the Federal Republic . Although located in the western part of the city, it was operated by the Deutsche Reichsbahn until the German railways were merged into Deutsche Bahn AG in 1994 . The S-Bahn station has been operated by BVG since January 9, 1984 and modernized accordingly. In the meantime, the station is no longer served by long-distance trains operated by Deutsche Bahn in favor of the main station that opened in 2006 . It was feared that City West would be decoupled from tourist traffic.

The U1 , U2 , U3 , U7 and U9 lines of the Berlin subway run in the Charlottenburg district .

people

Born in Charlottenburg

- (sorted by year of birth)

- Eduard Moritz von Flies (1802–1886), Prussian officer, most recently lieutenant general

- Ernst von Bredow (1834–1900), politician, manor owner and district administrator

- Leo von Caprivi (1831–1899), Vice Admiral of the Imperial German Navy, politician, Reich Chancellor as successor to Bismarck

- Otto March (1845–1913), architect

- Georg Michaelis (1852–1912), President of the Mainz Railway Directorate

- Georg Sobernheim (1865–1963), physician

- Carl Friedrich von Siemens (1872–1941), industrialist

- Paul Stanke (1875–1948), architect

- Paul Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1879–1956), chemist and industrialist

- Franz Hoffmann (1884–1951), architect

- Raul Mewis (1886–1972), Admiral of the Imperial German Navy

- Friedrich Fromm (1888–1945), army officer in World War II, most recently colonel general

- Paul Röhrbein (1890–1934), Kampfbundführer

- Fritz Bauer (1893–?), Racing cyclist

- Erich Karweik (1893–1967), architect

- August Thiele (1893–1981), naval officer, vice admiral in World War II

- Rüdiger von der Goltz (1894–1976), lawyer, defense attorney and politician ( NSDAP )

- Fritz Lindemann (1894–1944), general of the artillery and resistance fighter against National Socialism

- Werner March (1894–1976), architect

- Edit von Coler (1895–1949), Nazi propagandist, industrial spy , dramaturge and foreign press chief in the Reichsnährstand as well as Gestapo agent and special representative in Romania

- Heinrich Ruhfus (1895–1955), rear admiral in World War II

- Günter Worch (1895–1981), civil engineer

- Georg Bertram (1896–1979), Protestant theologian, pastor of the German Christians and university professor for the New Testament

- Paul Haehling von Lanzenauer (1896–1943), officer

- Hansi Bochow-Blüthgen (1897–1983), writer, editor and literary translator

- Franz Karl Meyer-Brodnitz (1897–1943), doctor and industrial hygienist

- Maria von Bredow (1899–1958), farmer and politician

- Ernst-Robert Grawitz (1899–1945), Managing Director of the German Red Cross, SS Obergruppenführer and General of the Waffen SS and "Reichsarzt SS and Police"

- Karl-Günther Heimsoth (1899–1934), physician, publicist and politician

- Kurt Lieck (1899–1976), actor and radio play speaker

- Veit Harlan (1899–1964), actor and director

- Walter Meidinger (1900–1965), photo chemist

- Franz-Josef Wuermeling (1900–1986), politician (CDU), Federal German Minister for Family Affairs from 1953 to 1962

- Hans Ilau (1901–1974), politician (FDP) and bank manager

- Gerhard Renner (resistance fighter) (1902–1945), resistance fighter against the Nazi regime

- Hellmut Lehmann-Haupt (1903–1992), German-American art historian and university professor

- Hans Bernd von Haeften (1905–1944), diplomat and resistance fighter against National Socialism

- Irmgard Keun (1905–1982), writer and Nazi victim

- Henri Lehmann (1905–1991), American scholar

- Heinz Brandt (1907–1944), major general in World War II and Olympic champion in show jumping

- Fritz Meyer-Struckmann (1908–1984), lawyer and banker

- Ottfried Neubecker (1908–1992), heraldist and vexillologist

- Ahasver von Brandt (1909–1977), historian and archivist

- Eberhard von Thadden (1909–1964), lawyer, head of department and Jewish advisor in the Foreign Office

- Sybille Bedford (1911–2006), German-British writer

- Robert Gysae (1911–1989), naval officer, submarine commander, most recently flotilla admiral of the German Navy

- Martin Sandberger (1911-2010), SS-Standartenführer and convicted war criminal

- Karl-Heinz Gerstner (1912–2005), journalist

- Fritz Tobias (1912–2011), author and ministerial official

- Otto Krüger (1913–2000), dancer, choreographer and ballet master

- Meret Oppenheim (1913–1985), Surrealism artist

- Hans-Joachim Krieger (1914 - unknown), SS functionary

- Johann Georg von Rappard (1915–2006), mill owner and genealogist

- Charlotte Salomon (1917–1943), painter

- Alfred Dürr (1918–2011), musicologist

- Hans-Joachim Marseille (1919–1942), fighter pilot

- Hoimar von Ditfurth (1921–1989), psychiatrist, pharmaceutical researcher, journalist, television presenter and popular science writer

- Inge Wolffberg (1924–2010), actress, voice actress and cabaret artist

- Harry Wüstenhagen (1928–1999), actor and voice actor

- Andreas Feldtkeller (* 1932), architect and urban planner

- Karl Veit Riedel (1932–1994), folklorist and theater scholar

- Friedrich-Wilhelm Kiel (* 1934), politician (FDP)

- Brigitte Weigert (1934-2007), painter and table tennis national player,

- Burckhard Garbe (* 1941), writer and Germanist

- Bernward Wember (* 1941), media scientist, book author and filmmaker

- Thomas Elsaesser (1943–2019), director and professor for film and television studies at the University of Amsterdam

- Michael Klein (* 1943), sculptor

- Drafi Deutscher (1946–2006), singer

- Henry Hübchen (* 1947), actor and composer

- Wolfgang Schulze (1953–2020), linguist

- Désirée Nick (* 1956), entertainer

- Christoph Marcinkowski (* 1964), Islamic scholar and Iranist

- Jan Peter Bremer (* 1965), writer

- Boris Aljinovic (* 1967), actor

- Lars Eidinger (* 1976), actor

- Prince Pi (* 1979), rapper

Connected to Charlottenburg

- (sorted by year of birth)

- Max Cassirer (1857–1943), local politician, entrepreneur and victim of National Socialism

- Adele Sandrock (1863–1937), actress; lived in Charlottenburg from 1905 to 1937

- Else Ury (1877–1943), children's book author and Nazi victim; lived in Charlottenburg from 1905 to 1933

- Trude Hesterberg (1892–1967), actress and singer; founded the Wilde Bühne in Charlottenburg in 1921

- Jan Bontjes van Beek (1899–1969), ceramist, sculptor and dancer as well as resistance fighter against National Socialism ; had a ceramics workshop in Charlottenburg and lived there

- Helmut Himpel (1907–1943), resistance fighter against National Socialism; lived in Charlottenburg

- Maria Terwiel (1910–1943), Catholic resistance fighter against National Socialism; lived in Charlottenburg

- Cato Bontjes van Beek (1920–1943), resistance fighter against National Socialism; lived in Charlottenburg

- Mietje Bontjes van Beek (1922–2012), painter and author; lived with her father Jan in Charlottenburg

- Brigitte Grothum (* 1935), actress and voice actress; graduated from the Ricarda Huch School in Charlottenburg

Mayor of the City of Charlottenburg

- 1705–1713: Friedrich I.

- 1717–1720: Friedrich Wilhelm I.

- 1720–1729: Daniel Friedrich Habichhorst

- 1731–1752: Heinrich Witte

- 1752-1753: unknown

- 1753-1766: E. Weider

- 1766-1775: F. Schomer

- 1775-1788: A. Krull

- 1788–1798: presumably: Justice Director Göring

- 1798–1800: E. Sydow and Göring

- 1801-1822: E. Sydow

- 1822–1842: Go. Advice from Schulz

- 1842: F. Trautschold

- 1842–1848: G. Alschefski

- 1848–1877: August Wilhelm Bullrich

- 1877–1898: Hans Fritsche (Lord Mayor since 1887)

- 1898-1899: Paul Matting

- 1899–1911: Kurt Schustehrus

- 1912–1920: Ernst Scholz

- Source: District Office Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf

See also

- List of stumbling blocks in Berlin-Charlottenburg

- List of streets and squares in Berlin-Charlottenburg

- List of cinemas in Berlin-Charlottenburg

literature

- Wilhelm Gundlach: History of the city of Charlottenburg. 2 volumes. Springer, Berlin 1905.

- Helmut Engel , Stefi Jersch-Wenzel , Wilhelm Treue , Historical Commission to Berlin (ed.): Geschistorlandschaft Charlottenburg. Charlottenburg, Part 1 - The historic city. Nicolai, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-87584-167-0 .

- Andreas Ludwig: The Charlottenburg case. Social foundations in an urban context (1800–1950). Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-412-12905-4 .

- Elke Kimmel, Ronald Austria: Charlottenburg in the course of history. From the village to the elegant west. Berlin Edition, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-8148-0137-7 .

- Clemens Maria Peuser, Michael Peuser: Charlottenburg in royal and imperial times - the richest city in Prussia. Michael Peuser Verlag, São Paulo 2004, ISBN 3-00-014695-4 .

- Katrin Achilles Syndram, Sonnenstuhl (Ed.): Charlottenburg opened. Schütze, Berlin 2005, ISBN 978-3-928589-20-8 (a series of maps).

- From idyll to big city - Charlottenburg district 1877–1920. District Office Charlottenburg of Berlin, Berlin 1987.

- Sonja Miltenberger: Charlottenburg in historical maps and plans. Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-932202-32-5 .

- Otto A. Borchert: Do you know Charlottenburg? What street names tell. Walter Göritz, Berlin 1930.

- Dorothea Zöbl: Where the king was mayor. Charlottenburg city history since 1700. Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-7861-2686-7 .

- Manfred Stürzbecher : From the history of the Charlottenburg health system . In: The Bear of Berlin , yearbook ed. v. Association for the History of Berlin , 29th year, Berlin 1980.

Movies

- Picture book: Berlin-Charlottenburg. rbb 2015. First broadcast on April 3, 2015. Film by Stephan Düfel. Shown in rbb on July 14, 2015, 8:15 p.m. to 9:00 p.m.

Web links

- Karl-Heinz Metzger: 300 Years of Charlottenburg in 12 Chapters From Charlottes Hof to Berlin City

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Stephan Brandt: The Charlottenburg old town. Sutton, Erfurt 2011, ISBN 978-3-86680-861-4 , p. 8.

- ↑ JGA Helling: Historical-statistical-topographical pocket book of Berlin and its immediate surroundings . HAW Logier, Berlin 1830, p. 51.

- ↑ Archive material in the Ethnological Museum Berlin, SMB: Process E 609/1887 (I / MV 0706 / IB 6 Africa)

- ^ Stephan Brandt: The Charlottenburg old town. Sutton, Erfurt 2011, ISBN 978-3-86680-861-4 , p. 7 f.

- ↑ The association Gaslicht-Kultur e. V. is committed to the preservation of Berlin's old gas lamps.

- ^ Official Journal of the Royal Government of Potsdam , 1876, p. 455, Textarchiv - Internet Archive

- ↑ Gundlach, 1905, p. 481 ff.

- ^ Wilhelm Gundlach: History of the city of Charlottenburg. First volume. Springer, Berlin 1905, pp. 560 ff., Textarchiv - Internet Archive

- ^ Historical Commission to Berlin, Helmut Engel et al. (Ed.): Historical landscape of Charlottenburg. Charlottenburg . Part 1 - The historic city . Nicolai, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-87584-167-0 , p. 270 ff.

- ^ Wilhelm Gundlach: History of the city of Charlottenburg . Springer-Verlag, 1905, attachment and p. 578 ff. Text archive - Internet Archive

- ^ Alphabetical street directory of Charlottenburg . In: Berliner Adreßbuch , 1910, Part 5, pp. 44–48.

- ^ Greater Berlin Act, Annex II .

- ↑ Wet triangle. In: District Lexicon Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf on berlin.de

- ↑ Björn Rosen: Chinese Charlottenburg Berlin's Chinatown. In: Der Tagesspiegel . June 17, 2013, accessed October 10, 2013 .

- ↑ neighborhood walk on 14.2.2004. In: berlin.de. September 8, 2014, accessed December 31, 2016 .

- ↑ Mayor and District Mayor