Völkerschau

Völkerschau (also called colonial exhibition or colonial show and recently called human zoo) describes a display of members of a foreign people . The heyday of the Völkerschauen in Europe was between 1870 and 1940. In Germany alone , over 300 non-European groups of people were presented during this time. Sometimes more than 100 people were put on display at the same time in these national and colonial shows. These displays were mass events that attracted millions of audiences in Europe and North America . They also took place away from the big cities in medium-sized and small towns.

From the 15th century onwards, explorers brought people from distant countries to Europe, who were initially shown to aristocrats and wealthy merchants. The explorers wanted to prove their success and the authorities complained about their ownership claims and wanted to demonstrate their openness to the world and their wealth. In the 19th century a branch of business emerged in which not only individual people or small groups from the most distant areas of the world were presented, but these events, of which up to 60,000 people attended, made considerable profits for the organizers. The European colonialism developing at that time wanted to show with people and colonial shows that colonies can also be of advantage for the people. In 1940 the Völkerschauen were closed and it was not possible to revive them in the 1950s.

term

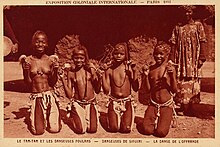

The term Völkerschau appeared in German-speaking countries as "Völkerschau auf Reisen" as early as 1840 as a book title in Theodor Mundt's travel reports from Europe and Africa. While Völkerschauen were run privately, the colonial shows were organized by the state. The first so-called colonial exhibition in Germany took place in Berlin's Treptower Park in 1896 , where more than 100 African inhabitants were shown for seven months in a so-called "Negro village" and stared at by visitors. In the racial theories of that time, Völkerschauen were also referred to as anthropological exhibitions or anthropological exhibitions . From 1901 to 1903 a magazine "Völkerschau" was published and in 1932 there was a scrapbook "Völkerschau in Bilder" for pictures from cigarette packets. In these decades the term Völkerschau referred to the representation and description of the display of exotic people. In 1904 the term was used for the first time for a display of "Tunisians" at the Oktoberfest in Munich. Hagenbeck attached importance to the fact that his events were called "ethnological-zoological exhibitions" and referred to them in his correspondence and autobiography as " national exhibitions ". In common usage they were called "caravans", "groups", "troops" or "exhibitions". In the “scientific context” of that time, the terms “human exhibition” and “human conceptions” were also used.

Recently, starting around 2010, it has been noticed in German-speaking countries that the term Völkerschau has been replaced by human zoo on various occasions in the media . The term human zoo has found its way into English usage .

history

In the Roman Empire it was common to display strangers and different people and also to destroy them, especially in the gladiatorial games .

15th to 17th centuries

Explorers in the early modern period often transported overseas residents to Europe on their return journeys. Born in Italy, Christopher Columbus (around 1451–1506) brought seven Arawak Indians to Spain from his first voyage of discovery . The Italian navigator Amerigo Vespucci (1454–1512) abducted around 200 Americans to Europe on his four voyages of discovery. The Portuguese navigator Gaspar Corte-Real (1450–1501) brought the first North American Indians to Lisbon in 1500 . When the Spaniard Hernán Cortés (1485–1547) returned in 1528, the first Mexicans arrived in Europe, who had to appear before Charles V and before the Pope. The French navigator Jacques Cartier (1491–1557) brought the first Native Americans to France.

Eskimos could already be admired in Bristol in 1501 and Eskimos in Copenhagen and Germany in 1721/1722 . In 1767 an Eskimo woman with child was exhibited in Antwerp.

In 1606 a man from Africa was put on display in Nuremberg, who had to present games with African animals and dogs. In 1610 a Huron Indian who was called Savignon became well known in Paris and marched through Paris for a year in Indian leather robes and a clean-shaven head . The name Pocahontas , a chief daughter who came to Europe with her husband, the tobacco grower John Rolfe, is still known today. She died before leaving Europe.

Many of the kidnapped people died on sea voyages to Europe or shortly after their arrival. These kidnapped people were brought before the court, introduced to rich merchants and shown at markets. They stimulated sculptors and painters, poets and writers incorporated them into their works, and they became the subject of treatises in theology, philosophy, and science.

18th century

In the 18th century, when the South Pacific was discovered, the French officer and navigator Louis Antoine de Bougainville (1729–1811) brought Aotourous, the first Tahitian to France, in 1769 after circumnavigating the world . When he left Paris in March 1790, he died of smallpox on the ship . The second Tahitian to come to Europe in the United Kingdom in 1775 was the servant Omai (also called Mai) of the British navigator James Cook (1728–1779). In contrast to before, both allegedly started the sea voyage to Europe voluntarily and had to return home because their sponsors were too expensive to maintain. Governor Arthur Phillip (1738–1814), the founder of the British convict colony Australia , took the Aborigines Bennelong (1764–1813) and Yemmerrawanne (1775–1794) to the United Kingdom on his return journey in 1792 , who became king on May 24, 1793 George III were presented.

The employment and display of so-called Moors was widespread among wealthy citizens in the 18th century and they served as porters, messengers and messengers. In the regimental orchestras in almost every country, the Moors had to make percussion instruments such as drums, timpani, cymbals, triangles or bell trees sound by striking them. They were so present that they also found their way into literature.

Explorers brought these people to Europe to stage themselves. This staging was supplemented by objects, animals and plants brought along, which were supposed to document the wealth of the newly discovered areas. With the presentation to the authorities, they wanted to document ownership, openness and wealth. European absolutism tried to justify the public with a new concept: Due to the insurmountable class boundaries within one's own people, the demarcation from a stranger could on the one hand be made into a new kind of communal experience and on the other hand linked to the "appreciation" of this stranger as long as it remained weaker. "Indian villages" with "real" Indians have existed in Europe since the 17th century. This connection of absolutism, submission and recognition through publication was still evident in the Viennese “high princely Mohren” Angelo Soliman , who was a member of the court and also a Freemason , but after his death in 1796 was not buried, but stuffed and exhibited in the natural history cabinet.

From the 19th century

In the course of the 19th century a line of business had emerged in which people were introduced to people in peoples' shows from the remotest regions of the world, which made considerable profits. With the heyday of colonialism towards the middle of the 19th century, the Völkerschauen experienced a great boom in Europe. People from foreign cultures were presented in the zoo or in the circus as well as at fairs, folk festivals, in variety shows and at commercial and colonial exhibitions in the most natural setting possible.

From 1870 the showman trade developed to an unimaginable extent, which was caused by the economic, political and social change. The population grew, the cities enlarged, the establishment of industrial forms of work, which was associated with the Sunday off, created the conditions for an entertainment industry and the need for relaxation from everyday work. From the 1880s onwards, local showman associations were founded in Germany that networked with national showmen. The company was even able to set up its own specialist newspaper, Der Komet , which formed a nationwide communication network for events, job advertisements, company advertisements and festive events. Later, an event calendar was also published, which provided information on the dates of the events across the entire Reich territory. Decisive for the abandonment of the displays of individual or several »exotic people« was that it could no longer reach the general public and folk shows were designed and organized with great success. Hagenbeck organized the first Völkerschau in Germany in 1875 with “resounding success”.

One of the most famous displays of "exotic people" was the "Hottentot Venus" in 1810. It was a woman from South Africa named Sarah Baartman , who was allegedly the daughter of a bushman killed by the bushmen. Because of her physique and body size, this woman was celebrated as the »missing link« between apes and humans and the visitors were asked to feel her body shape and gender. But there was also criticism of this display. After her death in 1813, her remains were exhibited in the Musée de l'Homme until 1974 and only handed over to the South African Embassy in Paris in 2002 so that they could be buried in South Africa.

After the German Empire also became a colonial power in Europe with the occupation of Togo and Cameroon in 1884 , this should be secured propagandistically and the first German colonial exhibition took place in Berlin in 1896. Altogether only two of the 50 or so colonial shows were organized by the state, the Berlin colonial exhibition from 1896 and the “Africa show” from 1935 to 1949. Only in these two colonial shows did people come from the German colonies. This propaganda instrument was intended to make it clear that colonies not only served the particular interests of individual elite circles, but also the overall interests of the economy, the military and society in imperialist Germany. Colonial exhibitions that took place in Germany from 1896 to 1940 should show the “little man” that German colonies also offer them “advantages and opportunities”. In order to increase the attractiveness of the colonial exhibitions, amusement parks were set up in addition to the colonial exhibitions, where the population could enjoy themselves such as at folk festivals with puppet and puppet theater, shooting galleries, in riding arenas, coffees and tea rooms, etc., including culinary specialties from the colonies. The main organizer was the "German Colonial Society" founded in 1887, which at times had up to 40,000 members. Other colonial private trading companies, industrial companies, geographical societies and associations also organized colonial exhibitions. In the 1920s the "Committee for German Colonial Propaganda" and in the 1930s the " Reichskolonialbund " organized the colonial exhibitions.

Non-colonial powers also organized Völkerschauen: at the Swiss National Exhibition in Geneva in the summer of 1896, in addition to a Village suisse, a Village noir with 230 Sudanese who lived in mud huts despite the cold.

The display of so-called “exotic peoples” was not limited to Germany. In other countries of ( Western ) Europe and North America, people shows were also held in zoological gardens , panoptics , at folk festivals and fairs, as well as in the context of colonial and world exhibitions. For example, more than 50 Völkerschauen took place in Vienna between 1870 and 1910, and the Basel Zoo was the venue for 21 shows. At the Paris World Exhibition of 1889, in addition to the inauguration of the Eiffel Tower, another main attraction in the former Jardin d'Acclimatation Anthropologique, which was transformed into the Jardin d'Acclimatation Anthropologique , was a huge peoples exhibition of the French colonial empire (1877-1912). At the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, 17 “native” villages were on display. As part of the world exhibition of 1897 in Brussels, a Congolese village was built in which 267 Africans lived during the exhibition. In the world exhibition in St. Louis of 1904 Patagonians and Filipino Igorot were exhibited.

The various national groups were mostly not only presented in one country, but by their international organizers, such as u. a. Carl Hagenbeck , sent on a European tour to increase profits.

After the First World War , the line of business initially collapsed. Business relationships around the world were destroyed for many companies. In the 1920s there were again Völkerschauen, but their popularity decreased significantly. To compete against competition, e.g. In order to survive, for example through the radio, the exhibitions became larger and more expensive. Friedrich Wilhelm Siebold organized several "Lippenneger" shows between 1930 and 1932 and the exhibition "Kanaken der Südsee" at the Munich Oktoberfest in 1931 .

The beginning of National Socialist rule marked the end of the Völkerschauen in Germany. At first there were a few show events with a similar concept, for example in 1937 a “native village” was shown in the Düsseldorf zoo. From 1935 to 1940, the German Africa Show toured through the German Reich, a variety-like program that increasingly approached the concept of the classic Völkerschau and promoted the recovery of the former colonies . In 1940 black people were banned from appearing, so that Völkerschauen could no longer be organized. After the Second World War there were hardly any Völkerschauen in Germany (for example an Apache show at Oktoberfest in 1950 , in 1951 and 1959 in the same place each with the theme Hawaii ) - the longing for the exotic now served film and television as well as the emerging long-distance travel.

In Switzerland, Völkerschauen took place widely from the 1870s, for example, in 1885 there was " Carl Hagenbeck's anthropological-zoological Sinhalese exhibition"; 10,000 tickets were sold on the first weekend. In addition to other occasions, for example, in the summer of 1925 a settlement was built in Altstetten for “popular amusement” in which 74 people from West Africa lived; In 1930 Zurich Zoo built a “Senegalese village” on the Flamingo Meadow. The Knee Circus held Völkerschauen on Sechseläutenplatz in Zurich until 1964. In 1955 a poster read “Afrika calls, Sitten- und Völkerschau. Negro from Sudan. Six men, three women, two children. ». In general, visitors did not go to such shows out of sensationalism, but out of a supposed interest in the culture of the peoples.

Völkerschauen

Showman

Carl Hagenbeck

In 1875 Carl Hagenbeck opened the first Völkerschau with Laplanders based on the idea of animal painter friend Heinrich Leutemann (1824–1905). During the stay in Hagenbeck's exhibition grounds, visitors were able to watch the people of Lapland go about their everyday life. Hagenbeck's show celebrated great success. The little Lapland show moved from Hamburg to Berlin. Then she traveled to Leipzig. In order to remove the exhibitions from the environment of show booths and entertainment venues, attempts were made from now on to find reputable exhibition locations so that the shows were respected by the bourgeoisie.

After the unexpected great success of Carl Hagenbeck's first Völkerschau, he quickly planned more. With the help of his connections to animal hunters all over the world, he brought three “Nubians” to Europe in 1876, and immediately afterwards an Inuit family from Greenland. In 1883 and 1884 he organized a Kalmyks - and a Sinhalese - or Ceylon show. With the opening of his zoo in Stellingen in 1907 at the gates of Hamburg, Carl Hagenbeck had his own exhibition area, where Somalis , Ethiopians and Bedouins performed.

Other showmen

Hagenbeck's Völkerschauen soon found imitators, who at the time were Eduard Gehring, Carl, Fritz and Gustav Marquardt, Willy Möller, Friedrich Wilhelm Siebold, the companies Ruhe und Reiche and Carl Gabriel .

The companies of Ludwig Ruhe and Carl and Heinrich Reiche were Hagenbeck's greatest competitors. Both were based in Lower Saxony and competed with Hagenbeck through Nubian and Iroquois shows , “Wild Africa” (1926) and the “Riesenpolarschau” (1930).

Carl Gabriel was rarely supraregional, but mostly only worked in Munich at the Oktoberfest. He owned a wax museum, a movie theater and later a cinema. With his "giant shows", which often showed over a hundred people on display, he attracted many visitors to the Oktoberfest and made it a multiple "exotic venue".

From human zoos in Freiburg and Basel developed Karl Küchlin the programs of his vaudeville -Theaters.

organization

The organization of the Völkerschauen was associated with great effort. A total of up to five years had to be planned for preparation and implementation for a Völkerschau. Recruitment began six months before the actual tour. The recruiters of the animal dealer Carl Hagenbeck were, for example, the north polar region traveler Johan Adrian Jacobsen or members of Hagenbeck's family.

Great care was taken to show children and adults of both sexes and different ages as possible so that visitors could learn more about the “family life” of the peoples. A contract between the organizer and the strangers stipulated the length of stay, the obligations during the show and the salary. Some shows had losses from various diseases, making medical examination mandatory.

Advertising and staging

The arrival of the participants caused quite a stir, including with parades through the city. The shows benefited from events such as death, wedding or birth of the exhibited and the resulting rush of visitors. Prominent visitors to the shows such as Otto von Bismarck also attracted even more audiences to the exhibition venue. Through numerous press connections, hundreds of articles appeared on such events. Post and trading cards, film and radio also contributed to the marketing. Posters were important advertising media: They were colorful, visually powerful and large. The posters from the Hamburg printing company Adolph Friedländer were the most popular .

The staging of the exhibitions could partly be compared with theater performances. That is why artists, jugglers and craftsmen were preferred to be brought to Germany. All participants had to be healthy and strong. There were three types of Völkerschauen: On the one hand, the “native village” that the viewer could walk through, then shows with regulated sequences of the presentations and the sideshow , which emphasized the physical difference compared to the Europeans. Often there were also mixed forms. Matching costumes and elaborately designed stages and backdrops that portrayed the homeland were also important.

The Völkerschauen mostly did not correspond to the reality and the true way of life of the peoples, but rather an image of the European clichés about foreign people that had arisen through books and stories (e.g. by Karl May ). For example, the Tierra del Fuego were portrayed as cannibals and had to eat raw meat, perform fights and war dances. India was characterized by its picturesque backdrops, splendid costumes and brightly decorated elephants. Völkerschauen have contributed significantly to the consolidation of racist attitudes. It was often a humiliating portrayal of foreign cultures.

People watching

In the 1930s, the interest in Völkerschauen and also the "scientific interest", which carried out research using extremely questionable methods, began to wane in "exotic" people. The reasons for this are complex. In science, research at home was replaced by field research , in which the behavior of people in their environment was examined. The NSDAP's interest in Völkerschauen was initially low. The Foreign Office approved in the later 1930s, the so-called " Africa show " only under the condition that "Unzuverträglichkeiten to the public" were excluded. The Africa show was well received by the population and the National Socialists came up with the idea to involve John Hagenbeck and so this event toured Germany from 1935 to 1940. In 1939 a »Cameroon Show« was held without Hagenbeck, there was no further such event, because the Foreign Office was of the opinion that this “type of colonial propaganda [...] met with a justified lack of understanding among broad layers of the German people”. Even if all Völkerschauen were banned in 1940, the attitude towards this was not uniform in the NSDAP. The National Socialists saw and feared above all a mixture of races in the Völkerschauen. Colonial propaganda was important to them, but not in the form of Völkerschauen and this propaganda should take place through lectures, slide shows and training courses.

Anne Dreesbach , author of the book Tamed Wilde , not only attributes the end of the Völkerschauen to the National Socialists, but also sees an essential factor in the emerging film industry, which had become a mass phenomenon since the 1920s. Not only did films make more impact, they were also easier to make.

When after the end of the Second World War in the 1950s the Völkerschauen were revived at the Oktoberfest in Munich and several Völkerschauen were held at various locations in the Federal Republic of Germany until 1959, the "age of the Völkerschauen" was over, largely due to the onset of long-distance tourism. In addition, there was the attitude of European societies in the 1950s and 1960s, which resulted from the experiences of National Socialism and the Second World War, was connected with the collapse of the European colonial empires and with the striving for independence of the overseas peoples.

racism

The Völkerschauen assumed the imaginary superiority of the "white man", although this was rarely shown on posters. Nevertheless, this feeling of superiority, colonialism and imperialism were the background of the Völkerschauen. The commercial Völkerschauen were racist , other cultures were appropriated and the people exhibited were exhibited exclusively for the enjoyment of the audience. It was not for nothing that Hagenbeck referred to the actors at the displays as "human material". Open colonial propaganda was seldom carried out, and open racism did not attract paying spectators.

The exotic people were co-opted and their ways of life depicted as primitive. Negative descriptions always came to the fore: what these peoples cannot, what they do not have and what they are not. Only their physical abilities were highlighted and praised. When assessing the appearance, the own ideals of beauty served as a template. The life presented had to correspond to the expectations of the audience; the productions often referred to the events of everyday family life, which also corresponded to that of Europeans, such as celebrating a birth, wedding with dance, etc. The original meaning such as decorating and painting the body, the meaning of rituals, dances and ceremonial acts remained hidden from the audience.

Whole continents like Africa had to correspond to racist images in the Völkerschauen, for example that of the presented Africans and the image of the North American Indians, which Karl May had shaped. The entire history of mankind was shaped in the Völkerschauen in the 19th century by the racist ideas of industrialized Europe and North America. The other peoples should now also reach this level of industrialization.

criticism

As early as 1872, the Munich police headquarters forbade the exhibition of an "Indian" at the Oktoberfest because "such displays ... run counter to human dignity ". The later criticism expressed that Völkerschauen were only productions and did not show the foreign culture. The exhibitions would be organized in such a way that the perception of the exhibited corresponded to the stereotypes of Europeans towards these peoples. The “superiority” of the citizens in Europe over the peoples of the whole world was also expressed linguistically in the advertising media.

Criticism also came from the ranks of the German Colonial Society , whose board member Fran Strauch, in a memorandum in 1900, accused the organizers of the purely commercial orientation and discussed their harmful influence.

As a result, in 1900 the “export of natives from the colonies for the purpose of exhibition” was banned in the German Reich.

Even today, various events cause criticism because they are seen in the historical context of Völkerschauen. When the Augsburg Zoo was planning its “African Village” event from June 9th to 12th, 2005, the zoo director Barbara Jantschke was accused of racism.

The protesters found in an open letter:

“The reproduction of colonial gaze relationships, in which black people can be viewed as exotic objects, as subhumans or subhumans in intimate unity with the animal world in an apparently timeless village-like environment and which the majority Germans can use as inspiration for future tourist travel destinations, is hardly considered to be to understand equal cultural encounters. "

Zoo director Barbara Jantschke said:

“These days are supposed to bring people closer to African culture and African products. Of course, this is managed by colored Africans, and they are happy to do so - we have more requests for stands than we can satisfy. If you mean by 'exhibiting', then there should no longer be any international sporting events where people of color can be seen. On the contrary, this event is intended to promote tolerance and international understanding and bring the people of Augsburg closer to African culture. "

Since the discussion that began in 1999 about the speech rules for the human park by the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk , Völkerschauen have also been criticized as a “human park”.

Movie

- “The wild ones” in human zoos. Director: Bruno Victor-Pujebet, Pascal Blanchard. France, 2017, 92 min.

literature

- Utz Anhalt: Animals and humans as exotic: The exoticization of the "other" in the foundation and development phase of the zoo. Technical Information Library (TIB) - Leibniz Information Center Technology and Natural Sciences and University Library Hanover, 2007, full text (PDF; 2.4 MB).

- Manuel Armbruster: “Völkerschauen” around 1900 in Freiburg i. Br. - Colonial exoticism in a historical context . Freiburg 2011, freiburg-postkolonial.de (PDF).

- Pascal Blanchard, Nicolas Bancel, Gilles Boëtsch, Éric Deroo, Sandrine Lemaire: MenschenZoos. Showcase of inhumanity . Susanne Buchner-Sabathy (translation). Ed. du Crieur Public, Hamburg 2012. 512 pages. ISBN 978-3-9815062-0-4

- Rea Brändle: Totally foreign, up close. Völkerschauen and their locations in Zurich 1880 - 1960 . Rotpunktverlag, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-85869-120-8

- Anne Dreesbach, Helmut Zedelmaier (eds.): Right behind the Hofbräuhaus real Amazons. Exoticism in Munich around 1900 . Dölling and Galitz, Hamburg 2003.

- Anne Dreesbach: Tamed Wild: The display of "exotic" people in Germany 1870-1940 . Campus-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 ( review by ak )

- Anne Dreesbach: Colonial exhibitions, national shows and the display of the "foreign" . European History Online , ed. from the Leibniz Institute for European History , 2012. urn : nbn: de: 0159-2012021707 .

- Gabi Eißenberger: Kidnapped, ridiculed and died - Latin American national shows in German zoos . Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-88939-185-0 .

- Angelika Friederici: Peoples of the world on Castan's stages , in: Castan's Panopticum. A medium is viewed , issue 10 (D3), Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-928589-23-9 .

- Cordula Grewe (ed.): The look of the stranger. Exhibition concepts between art, commerce and science . Stuttgart 2006.

- Sylke Kirschnick: Colonial scenarios in the circus, panopticon and lunapark . In: Ulrich van der Heyden, Joachim Zeller (eds.) ... Power and share in world domination. Berlin and German colonialism . Unrast-Verlag, Münster 2005, ISBN 3-89771-024-2 .

- Haug von Kuenheim : Carl Hagenbeck . Ellert & Richter Verlag, Hamburg 2007, pp. 95–117, ISBN 978-3-8319-0182-1

- Susann Lewerenz: Völkerschauen and the constitution of racialized bodies . In: Torsten Junge, Imke Schmincke (ed.): Marginalized bodies. Contributions to the sociology and history of the other body. Münster 2007, ISBN 978-3-89771-460-1 .

- Hartmut Lutz (ed.): Abraham Ulrikab in the zoo - diary of an Inuk 1880/81. von der Linden, Wesel 2007, ISBN 3-926308-10-9 (diary of one of the exhibited persons; engl. 2005 - The Diary of Abraham Ulrikab, ISBN 0-7766-0602-6 ).

- Volker Mergenthaler: Völkerschau - Cannibalism - Foreign Legion. On the Aesthetics of Transgression (1897–1936). Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-484-15109-9 .

- Balthasar Staehelin: Völkerschauen in the Basel Zoological Garden 1879-1935 . Basler Afrika Bibliographien, Basel 1993.

- Werner Michael Schwarz: Anthropological Spectacle. For the exhibition of “exotic” people, Vienna 1870–1910 . Turia and Kant, Vienna 2001.

- Hilke Thode-Arora: Around the world for fifty pfennigs. The Hagenbeckschen Völkerschauen . Frankfurt am Main / New York 1989.

- Stefanie Wolter: Marketing the foreign. Exotism and the beginnings of mass consumption . Frankfurt am Main 2005.

- Eskimos died of smallpox . In: Berliner Zeitung , July 8, 1994; on the occasion of the 150th birthday of the Berlin Zoo

radio

- Karin Sommer: The wild ones are coming. Völkerschauen and other curiosities . Bayerischer Rundfunk , June 2, 1996

watch TV

- "The wild ones" in human zoos . Arte media library from July 1, 2020

Web links

- Chapter from Stefan Nagel: Show booths . (PDF; 5.53 MB) Völkerschau - with many original quotes.

- Calendar sheet Hagenbeck's exotic show. Deutsche Welle , March 11, 1874

- The German Colonial Exhibition of 1896 in Treptower Park . German Historical Museum

- Kurt Jonassohn: On A Neglected Aspect Of Western Racism .

- ISD: "Africans in the zoo / We protest!" ( Memento from April 7, 2011 in the Internet Archive ), 2005

- Zoo shows Africans . ( Memento of December 13, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Der Tagesspiegel , May 28, 2005

- Online picture archive on the topic of Völkerschauen - postcards, photos, etc.

Individual evidence

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of “exotic” people in Germany 1870–1940. Frankfurt a. M. 2005, p. 11 ff.

- ↑ Manuel Armbruster: "Völkerschauen" around 1900 in Freiburg i. Br. - Colonial exoticism in a historical context . P. 3 ff.

- ↑ Ursula Trüper: The German Colonial Exhibition of 1896 in Treptower Park . In: Deutsches Museum (Ed.), Undated, accessed on July 29, 2020

- ^ Meyer's Large Conversational Lexicon . 6th edition. Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1909 ( zeno.org [accessed on December 11, 2019] Lexicon entry “Showings, anthropological”).

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of "exotic people" in Germany 1870-1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 . Pp. 320/321

- ↑ Christa Hager: You have to be naked, of course. In: Wiener Zeitung undated, accessed on July 27, 2020

- ^ Marc Tribelhorn: Human zoos . In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung from December 23, 2013

- ↑ Watch cannibals . In: Tagesspiegel from September 28, 2018

- ↑ Völkerschauen: People put on display like in a zoo . In: Deutsche Welle of March 10, 2017

- ^ Peter Burghardt: Racism. Remnants of the human zoo . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung of May 17, 2010

- ↑ Sina Riebe: Accusations of racism against Hagenbeck Hamburger are reminiscent of a cruel “human zoo” . In: Hamburger Morgenpost from July 3, 2020

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of "exotic people" in Germany 1870-1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 . Pp. 24/25

- ^ A b Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of "exotic people" in Germany 1870-1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 . P. 25.

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of "exotic people" in Germany 1870-1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 . Pp. 18-20

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of "exotic people" in Germany 1870-1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 . P. 21/22

- ↑ Elenor Dark: Bennelong (c. 1764-1813) . In: Australian Dictionary of Biography, 1966

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of "exotic people" in Germany 1870-1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 p. 24

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of "exotic people" in Germany 1870-1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 p. 24

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of "exotic people" in Germany 1870-1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 pp. 40 to 49

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of "exotic people" in Germany 1870-1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 p. 26 and 27

- ↑ Working Committee of the German Colonial Exhibition (ed.): Germany and its colonies in 1896; official report on the first German colonial exhibition ( online at Archive.org )

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of »exotic people« in Germany 1870–1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 pp. 249/250

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of »exotic people« in Germany 1870–1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 p. 251

- ↑ LE SAPAJOU: LE VILLAGE NOIR ET LE VILLAGE SUISSE DE L'EXPOSITION NATIONALE DE 1896 (accessed April 4, 2019)

- ↑ Werner Michael Schwarz: Anthropological Spectacle. For the exhibition of “exotic” people, Vienna 1870–1910 . P. 223 ff.

- ↑ Balthasar Staehelin: Völkerschauen in the Basel Zoological Garden 1879–1935. P. 35.

- ↑ Pascal Blanchard, Sandrine Lemaire and others: Human zoos as an instrument of colonial propaganda. In: Le Monde diplomatique , August 11, 2000, p. 16.

- ↑ Balthasar Staehelin: Völkerschauen in the Basel Zoological Garden 1879–1935. P. 27.

- ↑ Adam Hochschild: King Leopold's Ghost: a Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa . Papermac, London, 2000, ISBN 978-0-333-76544-9

- ^ Marshall Everett, "The book of the Fair: the greatest exposition the world has ever seen photographed and explained, a panorama of the St. Louis exposition," Philadelphia: PW Ziegler 1904, Chapter VI, "Giants at the Exposition," p 101 ff., Https://archive.org/details/bookoffairgreate00ever/page/100 and Chapter XIX, “The Study of Mankind”, p. 265 ff., Https://archive.org/details/bookoffairgreate00ever/page / 264

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of “exotic” people in Germany 1870–1940. Frankfurt a. M. 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 . P. 53.

- ^ Susann Lewerenz: The German Africa Show (1935-1940). Racism, Colonial Revisionism and Post-Colonial Conflicts in National Socialist Germany . Frankfurt / New York 2005. ISBN 3-593-37732-2

- ↑ tagesanzeiger.ch

- ↑ nzz.ch

- ^ Meyer's Large Conversational Lexicon . 6th edition. Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1909 ( zeno.org [accessed on December 11, 2019] Lexicon entry “Exhibitions, anthropological”).

- ^ Haug von Kuenheim : Carl Hagenbeck . Ellert & Richter Verlag, Hamburg 2007, pp. 96–98

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of "exotic" people in Germany 1870-1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 . P. 53

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of “exotic” people in Germany 1870–1940. Frankfurt a. M. 2005, p. 64 ff.

- ↑ voelkerkundemuseum-muenchen.de ( Memento from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Günter HW Niemeyer: Hagenbeck. History and stories . Hamburg 1972, p. 215 ff.

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of "exotic people" in Germany 1870-1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 pp. 306 to 316

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of "exotic people" in Germany 1870-1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 p. 314/315

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of "exotic people" in Germany 1870-1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 pp. 306/307

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of "exotic people" in Germany 1870-1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 p. 316

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of "exotic people" in Germany 1870-1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 p. 318

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Tamed savages. The display of "exotic people" in Germany 1870-1940. 1st edition Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2005, ISBN 3-593-37732-2 . Pp. 183 to 189

- ↑ Münchener Gemeinde-Zeitung , 1 (1872), No. 27 of July 4, 1872, p. 204 ( Google Books ).

- ↑ Deutsche Kolonialzeitung 1900, No. 44–46, pp. 500, 511 and 520

- ↑ http://ieg-ego.eu/de/threads/hintergruende/europaeische-begegierungen/anne-dreesbach-kolonialausstellungen-voelkerschauen-und-die-zurschaustellung-des-fremden

- ↑ Werner Balsen: Exotics for the human park . In: Frankfurter Rundschau , September 16, 2002.

- ↑ Utz Anhalt: In the human park . In: taz , May 3, 2007.

- ↑ "The Wild" in the human zoo. Director: Bruno Victor-Pujebet, Pascal Blanchard. France, 2017, 92 min. Original title: Sauvages, au coeur des zoos humains. First broadcast by arte , Sept. 29, 2018 ( on YouTube )