Sarah Baartman

Sarah "Saartje" Baartman (* around 1789 in South Africa ; † December 29, 1815 in Paris ) was a Khoikhoi who was brought to Europe as a young woman in 1810 and exhibited there due to its anatomical features ( fat throat ). She became well known in Great Britain as Hottentot Venus and in France as Vénus hottentote . After her death in 1815, she was dissected and partially preserved.

biography

origin

Thanks to the archive work of Pamela Scully and Clifton Crais, the early biography of Sarah Baartman in particular has become much clearer. She was born in Camdeboo ("green valley") into a family of Khoikhoi - called " Hottentots " in colonial literature. There she lived until his death on David Fourie 's farm Baartman's Fonteyn and then moved with her family near the Gamtoos River to the farm of a Cornelius Muller, who sold Sarah in 1795 or 1796 to the free black Pieter Cesars. This was an employee of a wealthy merchant in Cape Town , in whose house Sarah worked. After his death she moved to Pieter in 1799 and to his brother Hendrik Cesars in 1803. During this time Saartjie , as she was called by Sarah's diminutive , met Hendrik van Jong, a drummer in the Dutch army, and lived with him for almost two years until he returned to Europe. From him she had her second child who, like her first, died after giving birth. Because he was in economic difficulties, her employer got Sarah to perform as "Hottentottenvenus" in front of sailors and soldiers in the local military hospital for money. There she was noticed by the doctor Alexander Dunlop, who also had money problems. He had the idea to let Sarah perform in Europe. On April 7, 1810, he, Hendrik and Sarah left South Africa on the HMS Diadem for London.

London

Sarah Baartman appeared in London as Hottentot Venus . In September 1810, members of the upper class were given private screenings. From October, Baartman appeared publicly, where she danced, sang and played the ramkie stringed instrument . Their particular attractiveness was based on the Europeans as exotic and erotic body shape, on their very pronounced buttocks ( steatopygia ) and on the rumor that the inner labia (labia minora) are long drooping ("Hottentott apron"). The performance was reported to be immoral and it also violated the ban on the slave trade that had been in place since 1807 . The African Institution under Zachary Macaulay (the father of the historian Thomas Babington Macaulay ) offered to bring Sarah Baartman back to her homeland. However, she refused. It is unknown whether she was put under pressure, whether she feared returning home to the Cape, because her people there were persecuted with brutality bordering on genocide , whether she also enjoyed her stage appearances or what the exact reasons came together. At the trial, which was conducted in Dutch, she stated that she was not subjected to any coercion and that she had been promised half of the profit from the show.

English province

After this sensational judicial review, which ended with a warning to the impresario not to continue to display Sarah Baartman inappropriately, further appearances in London were out of the question, Hendrick Caezar roamed the English provinces with his “ freak ”. On December 1, 1811, Sarah Baartman was baptized by the Reverend Joshua Brooks, with the written permission of the Bishop of Chester, in Christ Collegiate and Parish Church in Manchester .

Paris

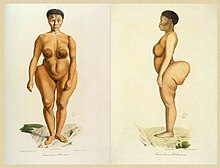

In 1814 she came to Paris under a new impresario, the trainer Réaux, and again caused a sensation, this time mainly in science. In the Jardin des Plantes she was presented to the assembled doctors, anatomists and natural historians covered with only shame and portrayed by professional graphic artists. She died at the end of 1815, allegedly of pneumonia.

The anatomist Georges Cuvier performed a dissection. The skeleton, brain and genitals were preserved after a plaster cast of the body was made. The painted plaster cast and the skeleton were exhibited in the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle , which later became the Musée de l'Homme , now housed in the Palais de Chaillot .

Post-history

Only essays by Stephen Jay Gould and Élisabeth de Fontenay brought the sexism and ethnocentrism of this exhibition practice into European consciousness in 1982 . Still, the French academic establishment, fearing a precedent, long refused to allow President Nelson Mandela to hand over the remains of Sarah Baartman to South Africa. The transfer took place in May 2002 and later the ceremonial burial at Hankey on the Gamtoos River in the Baviaanskloof area on August 9, 2002. The then incumbent South African President Thabo Mbeki gave the funeral address. The plaster cast of the “Vénus hottentote” is still on display in the Musée de l'Homme . The district of Cacadu in the South African province of Eastern Cape, in which her grave is located, was renamed " Sarah Baartman ".

The poem Tribute to Sarah Baartman , written by Diana Ferrus , had a not inconsiderable influence on the publication of Sarah Baartman's remains . The precedent of the member of the "Eskimos of New York", Minik Wallace , may also have played a role . The bones of his relatives had to be released by the American Museum of Natural History in 1993 and transferred to Greenland , where they were also solemnly buried.

See also

literature

- Clifton Crais, Pamela Scully: Sara Baartman and the Hottentot Venus. A Ghost Story and a Biography. Princeton, Oxford 2009.

- Elisabeth de Fontenay : Diderot, ou, Le matérialisme enchanté . Paris 1981, ISBN 2-246-23052-7 .

- Stephen Jay Gould : The Hottentot Venus, in Natural History 1982 , German in Stephen Jay Gould: The smile of the flamingos , Frankfurt 1995, pp. 229-240 ISBN 3-518-28771-0

- Sander Gilman : Hottentot and prostitute. An iconography of the sexualized woman . In: Sander Gilman (Ed.): Race, Sexuality and Epidemic. Stereotypes from the inner world of western culture . Reinbek, 1992, ISBN 3-499-55527-1 .

- Zoe S. Strother: Display of the Body Hottentot . In: Bernth Lindfors (Ed.): Africans on Stage. Studies in Ethnological Show Business . Bloomington, 1999, ISBN 0-253-21245-6 .

- Gérard Badou: The black Venus . Munich and Zurich 2001, ISBN 3-8284-5038-5 (original title: L'Énigme de la Vénus Hottentote .).

- Sabine Ritter: 'Présenter les organes génitaux'. Sarah Baartman and the construction of the Hottentottenvenus . In: Alienated Bodies. Racism as desecration of a corpse . Edited by Wulf D. Hund . Bielefeld: Transcript 2009, pp. 117–163

- Sabine Ritter: Facets of Sarah Baartman: Representations and reconstructions of the 'Hottentottenvenus' . Münster etc .: Lit 2010. ISBN 3-643-10950-4

- Gesine Krüger : 'Moving Bones. Unsettled Histories in South Africa and the Return of Sarah Baartmann '. In: Histories; unsettling and unsettled . Edited by Alf Lüdtke u. a. Frankfurt / M .: Campus 2010, pp. 233–250

- Rachel Holmes: The Hottentot Venus: the life and death of Saartjie Baartman: born 1789 - buried 2002 . Bloomsbury, London, 2007

- Sadiah Qureshi: Displaying Sarah Baartman, the 'Hottentot Venus' . In: Sci. Hist. No. XLII , 2004, pp. 233-257 ( negri-froci-giudei.com [PDF]).

Fiction and film

- Suzan-Lori Parks: VENUS, a drama in 3 acts , 1990–95

- Zola Maseko: The Life and Times of Sarah Baartman , documentary, 1998

- Barbara Chase-Riboud: Hottentot Venus, a novel , New York 2003

- Abdellatif Kechiche : Vénus noire , feature film, 2010

- Joanna Bator : Chmurdalia ("Wolkenfern"), novel, 2010

theatre

- Robyn Orlin : Have you hugged, kissed and respected your brown Venus today?

Opera

- Hendrik Hofmeyr and Fiona fall composed the 20-minute opera Saartjie , it was in November 2010, directed by Geoffrey Hyland in the Cape Town Opera premiered.

Web links

- Literature about Sarah Baartman in the catalog of the German National Library

- history

- Post-history

- Proposal for the law to return the remains of SB to South Africa with the poem by Diana Ferrus, presented to the French Senate by Sénateur M. Nicolas ABOUT on December 4, 2001

- Dossier on French law n ° 2002-323 of March 6, 2002 on the return of the remains of SB to South Africa with left to minutes of meetings.

- South African Government Information: Sarah Bartmann Dressing Ceremony, AUGUST 4, 2002

- South African Government Information: Sarah Bartmann Interment Ceremony, August 9, 2002, Hankey, Eastern Cape

- Other post-history links

- Gamtoos Tourism Information, the grave of the SB in Baavianskloof, still unfenced

- Gender and Women's Studies for Africa's Transformation, Yvette Abrahams, Colonialism, disjuncture and dysfunction: Sarah Bartmann's resistance , an approach from the perspective of gender research

- Mara Verna: "Hottentot Venus", interactive audio presentation with link list and bibliography. Conversations, interviews and speeches.

- Lucille Davie: Sarah Baartman, at rest at last

Individual evidence

- ↑ Information from Clifton Crais, Pamela Scully: Sara Baartman and the Hottentot Venus.

- ↑ Lyndel Prott V.: The Return of Saartjie Baartman ot South Africa. In: Lyndel V. Prott (Ed.): Witnesses to History. A Compendium of Documents and Writings on the Return of Cultural Objects. UNESCO Publishing, Paris 2009, p. 288

- ↑ Margit Hillmann: Voluminous artificial rear, cheeky springy . In: dradio.de, Deutschlandfunk, Corso, December 1, 2012 (December 2, 2011)

- ↑ http://www.gipca.uct.ac.za/project/five-20-operas-made-in-south-africa/

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Baartman, Sarah |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Sartjie; Saartjie; Sartjee; Saartjee |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Khoi stage actress |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1789 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | on the Gamtoos River, South Africa |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 29, 1815 |

| Place of death | Paris |