Irmgard Keun

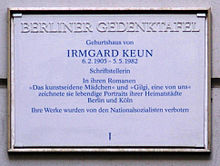

Irmgard Keun (born February 6, 1905 in Charlottenburg near Berlin, † May 5, 1982 in Cologne ) was a German writer .

Life

Irmgard Keun first spent her childhood in Berlin with her parents, the businessman Eduard Keun and Elsa Charlotte Keun, née Haese, and her brother Gerd, born in 1910. During the time in Berlin, the family moved several times until they moved to Cologne in 1913. Her father had meanwhile advanced to become a partner and managing director of the Cologne petrol refinery and had moved into the house at Eupener Strasse 19 in Cologne-Braunsfeld with his family . After graduating from the Teschner Protestant Girls' College in 1921, Keun first attended a commercial school in the Harz Mountains , then took private lessons in shorthand and typewriter at a Berlitz School . Then she worked as a stenographer. Keun attended drama school in Cologne from 1925 to 1927. Engagements in Greifswald and Hamburg followed , albeit with moderate success. For this reason, she ended her acting career in 1929 and began - encouraged by Alfred Döblin - to write. On October 17, 1932, she married the author and director Johannes Tralow in Cochem ; The marriage ended in divorce in 1937.

plant

Her first novel Gilgi, One of Us made Irmgard Keun famous overnight in 1931. Also, The Artificial Silk Girl (1932) became an instant sales success. It was sponsored by Döblin and Kurt Tucholsky , with whom, however, a controversy developed after allegations of plagiarism were raised against Das Kunstseidene Mädchen . Keun allegedly copied from Robert Neumann's novel Career, which was published in 1931. Neumann distanced himself - albeit only in 1966 - from this accusation in the epilogue to the new edition of Karriere and blamed the critics for the blame: “I never said anything like that, I don't claim it today - I hope Ms. Keun reads this assurance, which is just it comes a couple of decades late. Ms. Keun didn't need me either. "

In 1933/34 her books were confiscated and banned. Your application for membership in the Reichsschrifttumskammer was finally rejected in 1936. Keun went into exile (1936 to 1940), first to Ostend in Belgium and later to the Netherlands . During this time, the novels The Girl, With whom the children were not allowed to socialize (1936), After Midnight (1937), D-Zug third class (1938) and Child of all countries (1938), which are published in German-language exile publishers in the Netherlands could appear. During these years her circle of friends included Egon Erwin Kisch , Hermann Kesten , Stefan Zweig , Ernst Toller , Ernst Weiß and Heinrich Mann . From 1936 to 1938 she had a love affair with Joseph Roth , which initially had a positive effect on her literary work. She worked with Roth and made numerous trips with him (to Paris, Vilnius, Lemberg, Warsaw, Vienna, Salzburg, Brussels and Amsterdam). In 1938, Keun separated from Roth. After the Germans caught up with Keun in their country of exile when the German Wehrmacht invaded the Netherlands , she returned to Germany in 1940 and lived there until 1945 in illegality in her parents' house in Cologne-Braunsfeld . An SS man in the Netherlands helped her to produce false papers in the name of "Charlotte Tralow". It also helped that a hoax about her alleged suicide had been published by the Daily Telegraph .

After the war, Keun tried to reestablish lost contacts, met with Döblin and began an exchange of letters with Hermann Kesten that lasted for years. She worked as a journalist and wrote short texts for radio, cabaret and features , but could not gain a literary foothold again. At times she lived in very poor conditions in a shed on a ruined property in Cologne-Braunsfeld . There she went to the director of the Northwest German Broadcasting Corporation, Max Burghardt , and tried to get her to work together. At first she refused, but then a collaboration arose.

Her novel Ferdinand, the man with a friendly heart (1950) received little attention, and the books from the time of emigration also turned out to be unsaleable. In 1951 the daughter Martina was born, Keun kept the father a secret. From the mid-1950s onwards there was a friendship with Heinrich Böll , with whom she wanted to publish a fictitious "exchange of letters for posterity". The project failed because no publisher could be found. From the 1960s onwards there were no publications, Keun suffered from alcoholism and became impoverished. In 1966 she was incapacitated and was admitted to the psychiatric department of the Bonn State Hospital, where she stayed until 1972. After that she lived secluded in Bonn, from 1977 in a small apartment on Trajanstrasse in Cologne. A reading in Cologne and a portrait in Stern then unexpectedly led to a rediscovery of Keun's books. From 1979 onwards, her financial situation improved through new editions. In 1982 she died of lung cancer and was buried in the Melaten cemetery in Cologne .

Keun's last project belongs in the realm of the imagination: her autobiography No connection under this number, which she repeatedly announced after the renewed public interest. There was no line of this in her estate. This closes a circle of self-portrayals and false information about the biography that were typical of Irmgard Keun: When her first novel Gilgi appeared, she made herself five years younger to be as old as her protagonist. The Keun biographer Hiltrud Häntzschel therefore writes: "Irmgard Keun had a very special relationship to the truth of her life circumstances: sometimes sincere, sometimes reckless, sometimes inventive out of a longing for success, sometimes imaginative out of lust, dishonest out of necessity, sometimes secretive out of sparing."

Irmgard Keun's writing career began with novels that satirically and critically depict the lives of young women in the final phase of the Weimar Republic . The focus is on their striving for independence, the need to look after themselves, not to let themselves get down, but to survive. Keun's heroines are self-confident, quick-witted, have a sense of reality and the right to a happy life. What is missing, in addition to economic independence, is also emotional independence. They remain dependent on the money and attention of men. Irmgard Keun became an important representative of the " New Objectivity ". With her associative, funny-aggressive style, she oriented herself on the spoken language and the role model of the cinema: "But I want to write like film, because that's my life and it will be even more so," says the artificial silk girl.

After Gilgi appeared in 1932, Tucholsky wrote one of us about Irmgard Keun: “A writing woman with humor, look!” He praised Keun's “best little girl irony” and said: “Here is a talent (...) from this one A woman can become something. ”The bestseller editions , the naive charm of the female characters and the image of the fresh and cheeky young woman who is“ one of us ”, cultivated by the author, made Keun's books seem like pure entertainment. The literary importance was only recognized late by the critics . On her 100th birthday, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung read : “What Keun made out of the no longer entirely New Objectivity was artistic pop literature : a rapid mixture of hits and typewriters, inner monologues , delicate lyricisms and precisely heard Colloquial language, from advertising posters and revue numbers. "

After the Nazis seized power , Gilgi and Das Kunstseidene Mädchen were blacklisted as “ asphalt literature with an anti-German tendency” . In her later works Keun dealt with National Socialism and life in exile, especially in the novel After Midnight. In it she describes everyday life in Nazi Germany and paints a pessimistic picture of the futility of individual resistance to the dictatorship.

At the end of the 1970s, Irmgard Keun was rediscovered after long years of being forgotten - especially by feminist literary criticism .

The artificial silk girl became the first book for the city in Cologne in 2003 .

Awards / honors / prizes

- Marieluise Fleißer Prize of the City of Ingolstadt (1981)

Works

- Gilgi, one of us . 1931, novel.

-

The rayon girl - novel. Universitas, Berlin 1932.

- Many new editions, first Droste, Düsseldorf 1951; Paperback Ullstein, 2017, ISBN 978-3-548-28876-5 .

-

The girl with whom the children were not allowed . Allert de Lange Verlag, Amsterdam 1936.

- Numerous new editions, first Komet, Düsseldorf 1949, a. a. Claassen, Düsseldorf 1980, ISBN 3-546-45373-5 .

- After midnight . Querido Verlag, Amsterdam 1937. Novel. New editions: in GDR: Verlag der Nation, Berlin [-Ost] 1956; in FRG: Torchbearers Verlag Schmidt-Küster, Hanover 1961.

-

Third class express train . Querido Verlag, Amsterdam 1938. Novel.

- New editions: Claassen Verlag, Düsseldorf 1983 and: Gustav Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1984, ISBN 3-404-10357-2 .

-

Child of all countries . Querido Verlag, Amsterdam 1938. Novel.

- Frequent new editions: first Droste, Düsseldorf 1951; most recently List, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-548-60415-3 .

- Pictures and poems from emigration. Epoch, Cologne 1947, DNB 452 392 500 .

-

Women only ... 1949.

- New editions: If we were all good (= Bastei-Lübbe-Taschenbuch. Volume 10537). Edited and with an afterword by Wilhelm Unger . Bastei Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1985, ISBN 3-404-10537-0 ; Reprint of: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1983, ISBN 3-462-01548-6 (satires, autobiographies, scenes and considerations from the post-war period).

- I live in a wild vortex. Letters to Arnold Strauss , 1933–1947. Edited by Gabriele Kreis and Marjory S. Strauss. Claassen, Düsseldorf 1988, ISBN 3-546-45384-0 .

- Ferdinand, the man with the kind heart . 1950, novel.

- Joke article. Schleicher & Schüll, Einbeck / Han. 1951, OCLC 1040296451 (33 pp.).

- If we were all good Small incidents, memories and stories. Progreß-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1954; Licensed edition: Verlag der Nation, Berlin [-Ost] 1956, DNB 574296182 .

- Blooming neuroses. Box flowers. Droste, Düsseldorf 1962, DNB 452392683 .

- Irmgard Keun. The work. With an essay by Ursula Krechel . Ed. I. A. the German Academy for Language and Poetry and the Wüstenrot Foundation by Heinrich Detering and Beate Kennedy . Wallstein, Göttingen 2017, ISBN 978-3-8353-1781-9 .

Dramatizations

Stage versions

- The artificial silk girl. Book: Gottfried Greiffenhagen . Director: Volker Kühn , actress: Katherina Lange . Renaissance Theater Berlin, since 2003.

- The artificial silk girl. Stage version by Gottfried Greiffenhagen. Production by Tobias Materna at the Bonn Theater. With Birte Schrein in the lead role. Premiere: October 19, 2002. Resumption on September 3, 2005.

- After midnight. Book: Yaak Karsunke for the municipal theaters of Osnabrück, 1982.

- After midnight. Book: Yaak Karsunke. Director: Goswin Moniac, actors: Monika Müller, Jörg Schröder, Frankfurt 1988.

- An angel in Berlin. Book: Sandra Jankowski , Frank Klaffke . A play based on motifs by Irmgard Keun, staged at the Sturmvogel Theater, Reutlingen.

- Gilgi - one of us. Script and direction: Dania Hohmann with Anneke Schwabe in the leading role, St. Pauli-Theater, 2009.

Film adaptations

- One of us. Director: Johannes Meyer , screenplay: Irma von Cube , actors: Brigitte Helm , Gustav Dießl , Ernst Busch . Paramount, Paris 1932.

- The artificial silk girl . Director: Julien Duvivier , screenplay: Robert Adolf Stemmle , René Barjaval , Julien Duvivier, actors: Giulietta Masina , Gert Fröbe , Gustav Knuth , Ingrid van Bergen . Berlin 1959.

- After midnight . Director: Wolf Gremm , screenplay: Wolf Gremm and Annette Regnier, actors: Désirée Nosbusch , Wolfgang Jörg, Nicole Heesters , Hermann Lause and Irmgard Keun himself. Berlin 1981.

Radio plays based on works by Keun

- 1975: The artificial silk girl. - Director: Wolfgang Brunecker (radio play - Broadcasting of the GDR )

- 1997: Gilgi, one of us. - Director: Barbara Plensat (radio play - NDR )

- 2018: After midnight. - Director: Barbara Meerkötter (radio play - Der Audio Verlag , Berlin ISBN 978-3-7424-0189-2 , 96 min.)

literature

- Stefanie Arend , Ariane Martin (Eds.): Irmgard Keun 1905/2005. Interpretations and documents. Aisthesis, Bielefeld 2005, ISBN 3-89528-478-5 .

- Heinz Ludwig Arnold (Ed.): Irmgard Keun (= edition text + criticism . Journal for literature. Issue 183). Richard-Boorberg-Verlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-86916-020-7 .

- Frank Auffenberg: Of someone who set out to seek happiness and confuse research. Essay. In: Critical Edition . 1/2000, pp. 41–43 ( kritische-ausgabe.de [PDF; 32 kB]).

- Carmen Bescansa: Gender and power transgression in Irmgard Keun's novels (= Mannheim studies on literary and cultural studies. Volume 42). Röhrig, St. Ingbert 2007, ISBN 978-3-86110-424-7 .

- Heike Beutel, Anna Barbara Hagin (Ed.): Irmgard Keun. Telling contemporary witnesses, pictures and documents. Emons, Cologne 1995, ISBN 3-924491-48-8 .

- Jürgen Egyptien : Irmgard Keun in Cologne. Morio, Heidelberg 2019, ISBN 978-3-945424-47-6 .

- Hiltrud Häntzschel : Irmgard Keun. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2001, ISBN 3-499-50452-9 .

- Maren Lickhardt: Irmgard Keun's novels of the Weimar Republic as modern discourse novels. Winter, Heidelberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-8253-5691-0 .

- Ursula Krechel : Strong and quiet. Pioneers. Chapter: The destruction of the cold order. Irmgard Keun. Salzburg / Vienna 2015. Paperback edition, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-442-71538-1 , pp. 268–291.

- Gabriele Kreis: "What you believe is there". The life of Irmgard Keun. Arche, Zurich 1991, ISBN 3-7160-2120-2 .

- Ingrid Marchlewitz: Irmgard Keun. Life and work. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1999, ISBN 3-8260-1621-1 .

- Matthias Meitzel: "I long for peace, but I can't stand it". Two unknown letters to a friend. In: Sense and Form . 1/2020, pp. 5-12.

- Doris Rosenstein: Irmgard Keun. The narrative work of the thirties (= research on literary and cultural history. Volume 28). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1991, ISBN 3-631-42565-1 (Zugl .: Siegen, Univ., Diss., 1989).

- Liane Schüller: On the seriousness of distraction. Writing women at the end of the Weimar Republic: Marieluise Fleißer, Irmgard Keun and Gabriele Tergit. Aisthesis, Bielefeld 2005, ISBN 3-89528-506-4 .

- Liane Schüller: "Under the stones everything is a secret". Children's figures from Irmgard Keun. In: Writing women. A diagram in the early 20th century (= June . Magazine for literature and art. Issue 45/46). Edited by Gregor Ackermann and Walter Delabar. Aisthesis, Bielefeld 2011, ISBN 978-3-89528-857-9 , pp. 311–326.

- Volker Weidermann : The book of burned books. Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-462-03962-7 (on Keun pp. 188-191).

- Edda Ziegler: Forbidden - ostracized - expelled. Women writers in the resistance against National Socialism (= German volume 34611; part of: Anne Frank Shoah Library ). dtv, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-423-34611-5 , p. 49 ff.

Web links

- Literature by and about Irmgard Keun in the catalog of the German National Library

- Irmgard Keun. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations).

- Works by and about Irmgard Keun at Open Library

- Irmgard Keun. Hypies Hall of Fame. In: hypies.de. February 1999, archived from the original on October 6, 2007 .

- Sonja Hilzinger: Legends: Irmgard Keun for the 105th In: Deutsche Welle . February 4, 2010

- Carola Köhler: Pointy pen, inappropriate opinion, extremely hard-drinking. In: Berliner Stadtzeitung Scheinschlag . 05/2002

- Irmgard Keun in the database of Find a Grave (English)

- Link collection ( memento from April 13, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) of the University Library of the Free University of Berlin

- Christiane Kopka: 05.05.1982 - Anniversary of the death of Irmgard Keun In: wdr.de. ZeitZeichen series , May 5, 2017

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hiltrud Häntzschel: Irmgard Keun. P. 42 f.

- ↑ Volker Weidermann : Ostend 1936 - Summer of Friendship. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2015, ISBN 978-3-462-04600-7 .

- ^ Eduard Prüssen ( linocuts ), Werner Schäfke and Günter Henne (texts): Cologne heads . University and City Library, Cologne 2010, ISBN 978-3-931596-53-8 , p. 72 .

- ↑ Petra Pluwatsch: The ladies Keun. In: ksta.de. Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger , November 8, 2003, accessed on August 2, 2014.

- ↑ In his autobiography Burghardt describes in detail the encounter with the very repellent Irmgard Keun and describes her living conditions in the post-war years. Max Burghardt: I wasn't just an actor. Memories of a theater man. 3. Edition. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin / Weimar 1983, DNB 850068525 , p. 267 ff.

- ↑ Hiltrud Häntzschel : Irmgard Keun. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2001, ISBN 3-499-50452-9 , p. 7.

- ^ Eva Pfister: A long night about Irmgard Keun. "A writing woman with a sense of humor, look at it!" In: Deutschlandfunk . Long Night , August 18, 2018, accessed June 11, 2020.

- ↑ None of us and none of them. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . February 4, 2005, accessed December 17, 2018 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Keun, Irmgard |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Tralow, Charlotte (alias) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 6, 1905 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Berlin |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 5th 1982 |

| Place of death | Cologne |