Antunnacum

| Antunnacum | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Antunnacum , Antennacum |

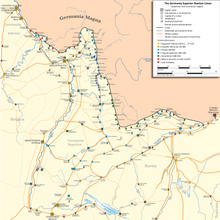

| limes | late antique Rhine Limes |

| section | Germania great |

| Dating (occupancy) | 1st to 5th century AD |

| Type | a) Cohort fort, vexillation fort? b) late antique fortress |

| unit | a) unknown Cohors Raetorum ? b) Milites Acincenses |

| size | a) unknown b) approx. 5.6 ha |

| Construction | a) wood-earth b) stone |

| State of preservation | Nothing more can be seen of the fort. Parts of a late antique bath have been preserved. |

| place | Then after |

| Geographical location | 50 ° 26 '24.5 " N , 7 ° 23' 51" E |

| Previous | Remagen Fort (northwest) |

| Subsequently | Burgus Neuwied-Engers (southeast) |

Antunnacum , today Andernach ( Mayen-Koblenz district ), was a Roman military camp , the crew of which secured a river crossing in the Middle Rhine Valley . Before the conquest of the Agri decumates and after the fall of the Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes around 159/160 AD , Antunnacum , located on the Roman Rhine Valley road , was also a border town. The ancient structures, now completely built over by the modern city, lie on the southern bank of the Rhine .

location

The early fortification was founded on the north-west end of a large, old island on the Rhine after the archaeologist Hans Lehner (1865–1938) thought . The fort there took up the area of a flood-proof hill, which is also known under the name "hill". The town hall is located here today. The vicus , the camp village, which later developed into an important trading place , was located to the west of this point on the island area. It could be proven that the "little hill" was already settled during the early La Tène period .

Investigations into the historical course of the Rhine showed that the branch branching off the main stream, which once surrounded the ancient settlement area, no longer had any water in Roman times, but was still swampy in places due to the tributary of the Kennelbach - known in the city of Schafbach held. The brook itself seeped away before it even reached the Rhine in the area of today's market square. North of Andernach, the old arm of the Rhine flows into the main stream with a bay that extends far into the country between the Krahnenberg and the "hill". At this point the valley of the Rhenish Slate Mountains narrows . The bay was a good natural harbor. Before that, however, the branch was traversed by two streams, the Felsterbach and the Antel, both of which flowed into the Rhine at some distance. The Antel was believed to be possibly related to the name of Antunnacum .

Research history

In 1902 the results of the excavations in Andernach carried out in 1900 and 1901 under the direction of Hans Lehner were published in the Bonn yearbooks . There the researcher submitted a detailed report on the state of research at the time. Only the investigations and excavations carried out by Günter Stein and Josef Röder around 1960 brought a significant enrichment to the facility presented at the time. After the demolition of the Weissheim malt house , an extensive excavation phase was carried out since 2010 under the direction of the General Directorate for Cultural Heritage Rhineland-Palatinate , Directorate for Regional Archeology, Koblenz, which covered an area of around 2500 square meters.

The Roman baths, discovered in 2006 next to the Romanesque basilica Maria Himmelfahrt and examined by the archaeologist Axel von Berg, were integrated into the building and opened to the public in 2009. Since then, parts of the thermal bath can be viewed through a glass dome in front of the parish hall.

Building history

Wood-earth warehouse

Through the conquests of the Roman general Gaius Iulius Caesar on the left bank of the Rhine , in the middle of the 1st century BC. BC also the Celtic precursor settlement of Antunnacum in the west of today's old town part of the Roman Empire. It remained and became the nucleus of the later town. Early Roman ceramic shards from the oldest Gallo-Roman strata were recovered from the lower Hochstrasse, Schaarstrasse and Agrippastrasse and date back to the turn of the century.

In order to protect the new river border from Germanic raids, apparently irregular units were first dug, which were probably made up of members of the local population. Graves on the Andernacher Martinsberg, which, among other things, contained the weapons of the deceased, point to such a force, which in addition to defending their settlement also secured the natural harbor . From the late Iberian-Claudian epoch between 30 and 50 AD, a regular Roman unit took over these tasks and built a wood-earth camp around 400 meters west of the Celtic settlement for the permanent garrison, but research cannot make any concrete statements about it. What is certain is that it was already on the "hill". It is possible that the wood and earth camp went under during the Batavian revolt (August 69 AD – Autumn 70 AD). One can only speculate about an immediate successor investment. At the latest with the construction of the Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes, Andernach became uninteresting as a possible garrison location for the Roman military leadership.

Stone fort

With the fall of the Limes in 259/260 AD, Antunnacum again became a border town and obviously a target of Germanic attacks. For example, the temple complex “In der Felster” on the Kranenberg and a previous building of the late Roman villa at the Marienstätter Hof were violently destroyed in the following years. Andernach came again into the focus of the Roman strategists. To secure the border area, a mighty fortification was built in the 4th century on the area of the core area of the mid-imperial settlement, which had a defensive wall around 910 meters long and 2.9 to 3 meters wide and enclosed around 5.6 hectares. Towards the foundation, the wall was set off by a 0.30 meter wide, partly stepped, partly sloping base area. In the foundation itself there were tufa blocks built as spoil alongside slate stones. Inside the fort, the defensive wall consists of Opus caementitium . Only the outside was carefully faced with tuff and slate stones. The basically rectangular system only adapted to the topography of the terrain on the south-east side, as the boggy oxbow lake of the Rhine was located there.

The Via principalis , the main camp street that cuts through the width of the fort, is still marked today by the course of the elevated street, while the church street at right angles to it takes up the direction of Via praetoria , which leads to the river bank via Porta praetoria - the dem Main gate of the garrison facing the enemy - left. The fort had four driveways equipped with gate towers as well as 14 proven intermediate towers at a distance of around 30 meters. Only on the Rhine side no towers were found. Two of the gates were facing each other, the Porta praetoria on the lower Kirchstrasse in the north, on the Wick in the south, in the west at the end of the Hochstrasse and in the east on the Hochstrasse between the confluence of Steinweg and Eisengasse. In addition to the garrison, the interior of the facility also included the core of the civil settlement. Ammianus Marcellinus names Andernach as Antennacum in connection with the battles of the later Emperor Julian against the Alemanni . After the garrison site was destroyed by this Germanic tribe, Julian had it rebuilt together with six other settlements as a supply base for his punitive expeditions carried out in 359. At the latest around 450/460 AD, the place finally fell to Frankish warriors, who among other things left a large number of graves.

Troop

Fort occupation

A Cohors Raetorum - a cohort of the Raetians - could have been in the early wood-earth camp , possibly just the vexillation of such an auxiliary force unit. This is indicated by the grave inscription of the soldier Firmus , son of Ecco , whose stone was found around 300 meters east of the "little hill" on Koblenzer Straße.

- [F] irmus

- Ecconis f (ilius)

- mil (es) ex coh (places)

- Raetorum

- natione M-

- ontanus

- ann (orum) XXXVI

- stip (endiorum) X [V] II (?)

- heres [e] x tes (tamento)

- po [sui] t // Fuscus

- serv [u] s // [

Translation: “Firmus, son of Ecco, soldier of the Raeter cohort, from the tribe of the Montani (inhabitants of the Ligurian Maritime Alps), 36 years old, with 14 (?) Years of service. The heir had (the tombstone) set according to the will. "

Since his slave Fuscus is shown next to Firmus, it is assumed that he was the heir of his master.

Along with this stone, the remains of two other soldiers' graves came out of the ground. The approximately three meter high tombstones made of Lorraine limestone were shipped to Antunnacum around 50/60 AD .

The Notitia dignitatum , a Roman state manual from the first half of the 5th century, describes Andernach as Castellum , which was subordinate to the command of the Dux Mogontiacensis . At that time a Praefectus was in charge of the Milites Acincenses unit stationed here .

Rhine fleet

A consecration stone for matrons kept in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn provides an indication that there could have been a Roman naval base in the Andernach harbor. In addition, this stone, which was created between 89 and 96 AD, could also indicate local members of the Rhine fleet . The name of the founder and the consecration itself suggest:

" Matribus / suis / Similio mil / es ex c (l) asse Ge / rmanica P (ia) F (ideli) D (omitiana) / pler (omate) Cresimi / v (otum) s (olvit) l (ibens) l (aetus) m (erito) "

“His matrons (donated by) Similius, soldier of the Germanic fleet - pious, loyal, Domitian - from the ship's crew (pleroma) of Cresimus. He has honored the vow gladly, joyfully and for a fee. "

In contrast, the skipper came Cresimus from the Hellenistic culture , his Latinized name means in Greek the Efficient .

bath

In addition to the Romanesque Basilica of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary , the remains of a well-preserved Roman hypocausted bathing complex from the 4th century came to light during the planning for a new parish house in 2006 , over which a cemetery had been located since the 8th century. The water basins were plastered with waterproof mortar and supplied with lead pipes.

Civil settlement

The knowledge about the early Roman civil and semi-civil life in Antunnacum , which was concentrated in the west of today's old town, is still very little. As the finds examined by Röder show, the continuity of settlement discovered there from the last phase of the Latène period to the early phase of the Roman occupation can be traced without any breaks. The area was still in the elevated area of the prehistoric Rhine island. In the north, the Rhine limited and protected the settlement area. In the west, south and east this task was taken over by the boggy river arm.

During the middle imperial period, in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, the area west of the market square up to Agrippastraße and between the Rhine and the railway line was densely built up. Another focus of the settlement was along the elevated road to the "hill". In this heyday of the town, which had grown large through trade and commerce, elaborate stone buildings replaced the small houses from the 1st century. At the corner of Kirchstrasse / Steinweg, south of the Maria Himmelfahrt basilica, the remains of a hypocausted building were discovered, which make it clear that the wealthy residents could afford some affluence. In 1882 a building inscription came to light on today's Merowingerplatz, which is dated to the years 202 to 208. The fragmentary inscription from the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus (193–211) mentions the completion of a building ([CV] M MVRIS POSIT [IS -]) at the behest of the governor at the time. However, since the text passage describing what was specifically built “with walls” was not preserved, the reference remains unclear. According to Lehner, there was a 75 meter long, east-west facing public building at the site of the find, which ended with a double row of fluted columns on the elevated road. A 0.75 meter diameter drum has been preserved from these columns in the Andernach City Museum. The function of this large structure is not known.

In the 4th century, the late antique fort was built in the area of the core area of the medieval settlement between Agrippastrasse in the west and the medieval market square in the east. The areas of the village further to the east along the elevated road and on the hill were obviously not included in the defense concept.

Burial grounds

The grave fields have been located south of the settlement since Celtic times, on the other bank of the marshy arm of the Rhine. A large number of grave finds at the foot of Martins (early Roman burials) and Kirchberg (early and late Roman burials) as well as in the east in front of the castle gate (early and late Roman burials) limit the location. Franconian graves have also been found in the two late antique cemeteries since the second half of the 5th century.

Two coemeterial churches discovered on the grave fields of late antiquity are a clear indication of the Roman origin of an early Christian community in Andernach, along with graves without gifts. It is assumed that these sacred buildings were subordinate to a parish church.

port

The port of Andernach made a particular contribution to the rise of the place during Roman times. In particular, the building material shipped there from the surrounding quarries, which has been needed to a large extent for the expansion of the cities along the Rhine since the early 1st century, has made a considerable contribution to this upswing. In particular, millstones made from basalt and tuff remained a constant bestseller. After the demolition of the Weissheim malt house, von Berg was able to examine the port area on a large scale for the first time in 2010. So far, in addition to the remains of buildings from the port facility, the Rhine-side city walls from early Roman and late ancient times have been observed over a length of 60 meters.

Minting

In the late antique Andernach a mint master's studio was built , which belonged to the so-called Mainz minting district . Boppard and temporarily Zülpich also belonged to this district . The extensive trade relations of this mint are proven by an Andernach Triens , which was found next to a Triens from Banassac in the south of France on the hay market in Cologne.

Post-Roman development

The geographer of Ravenna calls the settlement in the fort area , which then belonged to the Rhine-Franconian area, Anternacha around 500 AD and Venantius Fortunatus described Antunnacum as still strongly fortified in the 6th century. The walls of the late Roman fort lasted for many centuries and were still inhabited. As a result, the Merovingian Franconian kings owned a palace in the northeastern part of the fortification , to which a Genoveva chapel was attached. In 883 the Normans visited Andernach during their raids and destroyed the settlement areas in front of the fort walls.

Lost property

The finds from the excavations are exhibited in the Andernach City Museum. A remnant of the Roman aqueduct from the Eifel to Cologne can be viewed on a meadow in front of the hospital. Individual pieces are also kept in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn.

See also

List of forts in the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes

literature

- Josef Röder: New excavations in Andernach. In: Germania 39, 1961, pp. 208-213.

- Günter Stein, Josef Röder: The construction of the Roman city wall in Andernach. In: Saalburg Jahrbuch 19, 1961, pp. 8-17.

- Klaus Schäfer: Andernach in early Roman times . City Museum, Andernach 1986.

- Fritz Mangartz: The ancient stone quarries of the Hohen Buche near Andernach. Topography, technology and chronology . Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum, Mainz 1998, ISBN 3-88467-041-7

- Klaus Schäfer: Andernach - the hub of the ancient stone trade. In: quarry and mine. Monuments of Roman technical history between the Eifel and the Rhine. Verlag des Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseums, Mainz 2000, ISBN 3-88467-048-4 , pp. 83-109.

- Axel von Berg: Archaeological investigations at the Romanesque church Maria Himmelfahrt in Andernach, Mayen-Koblenz district. In: Andernacher Annalen 8, 2009/10, pp. 15–24.

- Axel von Berg: Excavation of the city center in the Roman town of Andernach on the Weissheim site of the former malt factory. In: Andernacher Annalen 10, 2013/14, pp. 7–22.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Josef Röder: New excavations in Andernach. In: Germania. 39, 1961, pp. 208-213; here: p. 210.

- ↑ a b c d e Klaus Schäfer: Andernach - hub of the ancient stone trade. In: quarry and mine. Monuments of Roman technical history between the Eifel and the Rhine. Verlag des Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseums, Mainz 2000, ISBN 3-88467-048-4 , pp. 83-109; here: p. 89.

- ↑ Hans Lehner: Antunnacum . In: Bonner Jahrbücher. 107, 1901, pp. 1-36.

- ^ Günter Stein, Josef Röder: The construction of the Roman city wall in Andernach. In: Saalburg Yearbook. 19, 1961, pp. 8-17.

- ^ Wellness facility from antiquity uncovered .

- ↑ Klaus Schäfer: Andernach - hub of the ancient stone trade. In: quarry and mine. Monuments of Roman technical history between the Eifel and the Rhine. Verlag des Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseums, Mainz 2000, ISBN 3-88467-048-4 , pp. 83-109; here: p. 87.

- ↑ a b c Klaus Schäfer: Andernach - hub of the ancient stone trade. In: quarry and mine. Monuments of Roman technical history between the Eifel and the Rhine. Verlag des Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseums, Mainz 2000, ISBN 3-88467-048-4 , pp. 83-109; here: p. 93.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus 18, 2, 4.

- ↑ a b Klaus Schäfer: Andernach - hub of the ancient stone trade. In: quarry and mine. Monuments of Roman technical history between the Eifel and the Rhine. Verlag des Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseums, Mainz 2000, ISBN 3-88467-048-4 , pp. 83-109; here: p. 95.

- ↑ CIL 13, 7684 ; Harald von Petrikovits : The tombstone of the Firmus . In: Harald von Petrikovits: The Roman armed forces on the Lower Rhine. Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1967, p. 54; Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz): Römische Kastelle , Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 35 (with ill.).

- ^ Leonhard Schumacher: Slavery in antiquity. Everyday life and fate of the unfree. CH Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3406465749 , p. 80.

- ↑ Notitia Dignitatum 39, 11.

- ↑ CIL 13, 7681 ; Heinrich Clemens Konen: Classis Germanica. The Roman Rhine fleet in the 1st – 3rd Century AD Scripta Mercaturae Verlag, St. Katharinen 2000, ISBN 3895901067 , p. 334.

- ↑ a b Klaus Schäfer: Andernach - hub of the ancient stone trade. In: quarry and mine. Monuments of Roman technical history between the Eifel and the Rhine. Verlag des Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseums, Mainz 2000, ISBN 3-88467-048-4 , pp. 83-109; here: p. 92.

- ↑ CIL 13, 7683a .

- ^ Stefan F. Pfahl, Marcus Reuter : Weapons from Roman individual settlements on the right of the Rhine. In: Germania. 74, 1996, pp. 119-167; here: p. 139, footnote.

- ↑ Markus Scholz : Ceramics and history of the Kapersburg fort - an inventory. In: Saalburg yearbook. Volumes 52–53, 2002/2003, Mainz 2003, pp. 9–282; here: p. 55.

- ^ Karen Künstler-Brandstädter: The building history of the Liebfrauenkirche in Andernach. Bonn, 1994, p. 18.

- ↑ Bernd Päffgen, Gunther Quarg: The coins found in the Merovingian period from the excavations on the Heumarkt in Cologne. In: Kölner Jahrbuch. Volume 34, 2001, pp. 749-758; here: p. 752.