Boppard Fort

| Boppard Fort | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Bodobrica , Bodobriga , Baudobriga , Baudobrica |

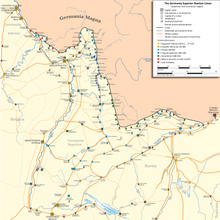

| limes | Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes |

| section | Germania great |

| Dating (occupancy) | 4th century AD |

| unit | milites balistarii |

| size | 308 m × 154 m |

| Construction | stone |

| State of preservation | rectangular system with projecting horseshoe-shaped towers, enclosing walls and defense towers partly. still in good condition. |

| place | Boppard |

| Geographical location | 50 ° 13 '54.1 " N , 7 ° 35' 28.3" E |

| height | 79 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Burgus Lahnstein (north) |

| Subsequently | Fort Oberwesel (southeast) |

The fort Boppard ( Latin Bodobrica , including: Bodobriga , Baudobriga or Baudobrica ) was a late Roman military camp on the Rheintalstraße whose crew "wet" for security and surveillance tasks at the border (ripae) of the Rhine was responsible. Today the plant is located in the center of Boppard , a town in the Rhein-Hunsrück district in the Federal Republic of Germany. The remains of the ancient fortifications are of particular interest for scientific research due to their exceptionally good state of preservation.

location

Roman settlements at this easily accessible location on the Middle Rhine between Taunus and Hunsrück can be traced back to the 1st century. Historical sources from the 2nd – 3rd centuries Century like the Tabula Peutingeriana and the Itinerarium Provinciarium Antonini Augusti mention the settlement as Bouobriga and Bontobrice respectively. The name probably goes back to an earlier Celtic settlement Boudobriga . The remains of this Roman fort are located in today's old town center of Boppard. The fort was built on a slight hill above the Rhine and thus on a flood-free area. It was centrally located between the forts Oberwesel and Andernach.

Research history

During the construction of the Boppard sewer system in 1939, several archaeological finds were uncovered and published in the Bonn yearbooks in 1941 . Proof of the western side of the Roman fort fortifications at tower 2 and 3 could be provided. Until then it was assumed that part of the fort was destroyed by the construction of the railway line on the left bank of the Rhine . In addition, two Franconian graves with additions were found. One of the interesting single finds that came to light was a Cautes , a figure from the Mithras cult .

In the course of a research program launched in 1959 to measure Roman fortifications in cities on the Middle Rhine, the remains of several watchtowers of the fortifications were uncovered. On the basis of this research program, the fort was examined from 1959 to 1962 by the art historian Günter Stein (1924–2000). This research work, which arose in connection with the Technical University of Berlin , was published in the Saalburg Yearbook 23 in 1966 and has served as the basis for all subsequent studies ever since.

The first systematic excavations were carried out between 1963 and 1966 during renovation work on the St. Severus Church and construction work on the market square by the then Office for Prehistory and Early History in Koblenz . An early Christian baptismal font from the 5th century was found during the excavations under the St. Severus Church. Further excavations were carried out in 1977 in connection with road repairs on Bundesstrasse 9 at the west gate and on the southern part of the western fort wall. The course of the western section of the wall could be determined, and the presumed western gate on today's Oberstraße could also be detected.

Further extensive excavations were carried out in connection with the relocation of federal highway 9 and the planned construction of a police station from 1989 to 1995. These were carried out in the area of the so-called bull stable in the southern apron and in the interior of the fort walls on Angertstrasse. There the fortress wall could be exposed over a length of more than 55 m. Tower 8 is only up to the current surface level, while Tower 9 has been preserved up to a height of eight meters. Due to these finds, the monument office prohibited the construction of the police station and demanded that the area be cleared.

At the beginning of the 21st century, a row of houses on the western wall of the fort was demolished as part of the surrounding design for the construction of an underground car park, and a 50-meter-long section of the wall is now freely accessible again.

Building history

After the Rhine became the border of the Roman Empire again in the 3rd century, the Bodobrica fort, around 308 × 154 meters in size , was built to protect against the Germanic tribes around the middle of the 4th century AD. This defense system was about a kilometer southeast of the settlement at that time and was surrounded by an eight meter high wall with probably 28 towers. The fortress-like bulwark served as a military base and trading center. In contrast to other late antique forts in the Rhineland, such as those in Remagen, Andernach, Koblenz, Bingen and Mainz, no existing buildings had to be taken into account. The fort at Boppard seems to have been built as a planned construction based on geographical, military and economic considerations.

On the field side, the defensive wall association consisted of small blocks , mostly made of greywacke . More or less heavily hewn stones were observed on the city side and inside the towers. Layers in the form of herringbone patterns ( Opus spicatum ) were built in at different heights . At one of the defense towers, the upper part of which was still preserved, the remains of two “loopholes” could still be observed under the medieval construction. A similar finding is also available from Andernach ( Antunnacum ) .

The fortification of the late antique fort Boppard is one of the best preserved of its kind in Germany and can be visited freely. During excavations, the remains of the thermal baths as well as several early Christian graves from the 7th century were uncovered.

investment

Fort

The fort had a size of 308 m × 154 meters , which corresponds to a walled area of around 4.6 hectares. The stone defensive wall was three meters thick, only on the Rheinfont it was measured with only two meters. In places the wall is still nine meters high. On the outer wall there were presumably a total of 28 round towers at regular intervals of around 27 meters. At least the southern fort wall was additionally secured by a trench in front of it. On the narrow sides of the fort to the west and east, there was an entrance each without gates or towers. A narrow gate could be detected on the south side and such a gate is also suspected on the north side, but this could not be detected. The Rheintalstraße led south past the fort and a main road ran through the fort, which corresponds to the current course of the Oberstrasse. A special feature are the strikingly massive towers, which reached a height of 10 meters and a diameter of 8.70 meters. They were used to station slingshots and arrow guns for the milites balisarii stationed in Boppard .

Fort bath

At the current location of the St. Severus Church there was a military bath that was built together with the fort. It was 50 m × 35 m in size and was built directly onto the north wall. The arrangement of its rooms corresponded to the usual building scheme of Roman baths. The building consisted of schisty greywacke and had brown-red exterior plaster. The roof was covered with red tiles and the windows were glazed.

A visitor came through a porch to the dressing rooms and from there to a room leaning against the fort wall with a floor area of 20 m × 9 m . This was probably used as a multi-purpose room. Another room with an apse adjoined the room to the east . This was equipped with underfloor heating and served as a warming room. The actual bathing wing connected to this room to the south. It consisted of a cold bath, a warm bath and a sweat bath. The fresh water for the basins was brought in from the slopes to the south and the wastewater was channeled into the Rhine through a lead channel. The bathing pools had a maximum water depth of 80 cm.

Coins of the Emperor Constantius were found under the floor of the changing room. These were minted between 341 and 346. Timestamps from the 22nd Legion were also found. This allows the use to be dated to 352/355 at the latest. After the fort was abandoned at the beginning of the 5th century, the fort bath was built over with a church, the forerunner of today's Severus Church.

Vicus

The early Roman settlement had Celtic origins. Linguistic research and written records suggest that this originally Celtic village was called Bodobrica. The village was located directly on the Rhine at the entrance to the Mühltal. The Rheintalstrasse was connected to the Ausoniusstrasse through the Mühltal . The fishing and trading village had its heyday between the 1st and 3rd centuries. Finds from the late Roman period were no longer made in this area. It can therefore be assumed that the settlement was relocated to the fort built in the middle of the 4th century. This is located about one kilometer east of the original settlement.

The vicus extends for about 50 m and consisted of permanent houses, some of which had a basement. The residents were quite wealthy during the 2nd and 3rd centuries, which can be deduced from the elaborate tombs that were erected along the Roman highway.

Troop

According to the Notitia dignitatum , a Roman state manual from the first half of the 5th century, fortress artillery workers were stationed in the fort milites balistrarii . The fort was under the command of the general of Germania I , the Dux Mogontiacensis in Mainz.

Lost property

The baptismal font from the 5th century found during excavations between 1963 and 1966 under St. Severus Church was left in its original location. When the interior of the church was restored again in 2010 and 2011, the room and the access to the baptismal font were also rebuilt. Since December 2011, this baptismal font can therefore be viewed during church tours.

A terracotta figure was found in one of the former houses of the vicus . It is a representation of the Celtic horse goddess Epona , who sits on the side of the lady's seat on a horse. The clay statue is twelve centimeters high. The importance of the find results from its rarity and the good preservation of the colors. Today the statue is in the Landesmuseum Koblenz , a copy is also exhibited in the museum of the city of Boppard in the electoral castle . In addition, an enlarged copy was set up near where it was found.

Three characteristic graves of the more than 40 grave pits that were found during the excavations between 1989 and 1990 in today's archaeological park have been preserved and preserved there.

Other finds from Roman times are exhibited in the city's museum in the electoral castle in Boppard.

Post-Roman development

After the withdrawal of the Roman troops, the civil population continued to live in the Roman fort. Around 406/407 the military bath was destroyed by fire. Around the middle of the 5th century, the predecessor of today's St. Severus Church was built on this site.

The fort walls served as the city wall of the medieval city until the 12th century . The northern wall was demolished at the latest when today's St. Severus Church was built. This had become superfluous because a wall closer to the Rhine had been built. However, it was not until the Archbishop of Trier, Baldwin of Luxembourg , to whom Boppard was pledged by Henry VII., That the new residential areas in the east and west were protected by a medieval city fortification and thereby bound the Roman fort walls. Thus only the southern fort wall remained an outer wall of the medieval city fortifications.

In the 19th century even larger parts of the former fort were destroyed. In 1969, when the new hall at the Römer was built, an eight-meter-long and four-meter high section of the western wall was demolished against protests from the citizens of Boppard. This hall was demolished together with other buildings in 2007/2008 and the wall was exposed. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Federal Republic of Germany acquired land in Boppard in order to implement a partial bypass for Bundesstraße 9 . The Federal Republic also became the owner of the south-western corner of the Roman fort. At the beginning of the 1990s, Bundesstraße 9 was relocated, with parts of the acquired southwestern walls with towers 1 to 5 being demolished with the approval of the preservation authorities.

Monument protection

Fort Boppard has been part of the Upper Middle Rhine Valley UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2002 . In addition, this ground monument is protected as a registered cultural monument within the meaning of the Monument Protection and Maintenance Act (DSchG) of the state of Rhineland-Palatinate. Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to approval, and accidental finds are reported to the monument authorities.

See also

literature

- Hans Eiden: Military bath and early Christian church in Boppard on the Rhine. In: Excavations in Germany funded by the German Research Foundation 1950–1975. Volume 1. Part 2. Mainz 1975, pp. 80-98.

- Hans Eiden: A Christian cult building in the late Roman fort Boppard. In: Files of the VII International Congress on Christian Archeology. Trier, 5th to 11th September 1965 (= Studi di antichità cristiana. 27). Città del Vaticano, Berlin 1969, pp. 485-491.

- Hans Eiden: The results of the excavations in the late Roman fort Bodobrica (= Boppard) and in the Vicus Cardena (= Karden). In: Joachim Werner, Eugen Ewig (Ed.): From late antiquity to the early Middle Ages. (= Lectures and research. 25). Jan Thorbecke Verlag, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-7995-6625-2 , pp. 317-345.

- Hans Eiden: Late Roman fort bath and early Christian church in Boppard. (= Excavations on the Middle Rhine and Moselle 1963–1976. = Trier magazine. Supplement 6). Tafelband 1982, pp. 215-265.

- Hubert Fehr : The west gate of the late Roman fort Bodobrica (Boppard). In: Archaeological correspondence sheet. 9, 1979, pp. 335-339.

- Hubert Fehr: Excavations on the southern front of the late Roman fort of Boppard. In: Archeology in Germany . Volume 3, 1991, p. 53.

- Eberhard J. Nikitsch: New, not only epigraphic reflections on the early Christian inscriptions from Boppard. In: New Research on the Beginnings of Christianity in the Rhineland. (= Yearbook for Antiquity and Christianity . Supplementary Volume 2). Aschendorff Verlag, Münster 2004, pp. 209-223.

- Ferdinand Pauly : The Boppard Fort. In: From the history of the Diocese of Trier. Issue 1–3. Trier 1968-1970, pp. 7-14.

- Sebastian Ristow : The term “early Christian” and the classification of the first church in Boppard on the Rhine. In: Ulrike Lange, Reiner Sörries (ed.): From the Orient to the Rhine. Encounters with Christian Archeology. Peter Poscharsky on his 65th birthday. Dettelbach 1997, pp. 247-256.

- Josef Röder: New excavations in Boppard. In: All about Boppard. No. 53, 1960.

- Günter Stein: Building recordings of the Roman fortification of Boppard. In: Saalburg yearbook. 23, 1966, pp. 106-133.

- Hans-Helmut Wegner : Boppard. Vicus, fort. In: Heinz Cüppers : The Romans in Rhineland-Palatinate. Licensed edition of the 1990 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-60-0 , pp. 344–346.

- Klemens Wilhelmi: Emergency excavations in the area of the W and S gate of the Rhine castles in Boppard and Koblenz. In: Roman Frontier Studies 1979. pp. 567-586.

Web links

- Fort Boppard in: regionalgeschichte.net

- Roman fort, Boppard in welterbe-mittelrheintal.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c History Association for the Middle Rhine and Vorderhunsrück (ed.): From Iron Age fortifications to Prussian fortresses . Boppard 2009, p. 34 ff .

- ^ A b c d Klaus Brager: Archaeological preservation of monuments . In: Heinz E. Missling (Ed.): Boppard. History of a city on the Middle Rhine . Third volume. Dausner Verlag, Boppard 2001, ISBN 3-930051-02-8 , 5.4.

- ↑ a b c Victor Heinrich Elbern (ed.): Roman city tower in Boppard. In: The first millennium. Culture and art in the emerging West on the Rhine and Ruhr. Panel tape. Verlag L. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1962, p. 6.

- ↑ Hans-Helmut Wegner : The prehistory and early history in the settlement area Boppard . In: Heinz E. Missling (Ed.): Boppard. History of a city on the Middle Rhine . First volume: From the early days to the end of the electoral rule . Dausner Verlag, Boppard 1997, ISBN 3-930051-04-4 , p. 38-40 .

- ↑ Hans-Helmut Wegner: The prehistory and early history in the settlement area Boppard . In: Heinz E. Missling (Ed.): Boppard. History of a city on the Middle Rhine . First volume: From the early days to the end of the electoral rule . Dausner Verlag, Boppard 1997, ISBN 3-930051-04-4 , p. 40 .

- ↑ a b c Hans-Helmut Wegner: The prehistory and early history in the settlement area Boppard . In: Heinz E. Missling (Ed.): Boppard. History of a city on the Middle Rhine . First volume: From the early days to the end of the electoral rule . Dausner Verlag, Boppard 1997, ISBN 3-930051-04-4 , p. 41 .

- ↑ a b Hans-Helmut Wegner: Boppard. Vicus, fort. In: Heinz Cüppers : The Romans in Rhineland-Palatinate. Licensed edition of the 1990 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-60-0 , pp. 344–346.

- ↑ Hans-Helmut Wegner: The prehistory and early history in the settlement area Boppard . In: Heinz E. Missling (Ed.): Boppard. History of a city on the Middle Rhine . First volume: From the early days to the end of the electoral rule . Dausner Verlag, Boppard 1997, ISBN 3-930051-04-4 , p. 41-42 .

- ^ A b Hans-Helmut Wegner: The prehistory and early history in the settlement area of Boppard . In: Heinz E. Missling (Ed.): Boppard. History of a city on the Middle Rhine . First volume: From the early days to the end of the electoral rule . Dausner Verlag, Boppard 1997, ISBN 3-930051-04-4 , p. 31-32 .

- ↑ Hans-Helmut Wegner: The prehistory and early history in the settlement area Boppard . In: Heinz E. Missling (Ed.): Boppard. History of a city on the Middle Rhine . First volume: From the early days to the end of the electoral rule . Dausner Verlag, Boppard 1997, ISBN 3-930051-04-4 , p. 47 .

- ^ A b State Office for Monument Preservation (ed.): The art monuments of Rhineland-Palatinate . tape 8 : The art monuments of the Rhein-Hunsrück district. Part 2. Former county St. Goar, the first town of Boppard I . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-422-00567-6 , p. 450-451 .

- ↑ M. Thoma: Roman fort. regionalgeschichte.net .

- ↑ The “Central-Café” in Boppard is being demolished. In: Rhein-Hunsrück-Zeitung. December 14, 2007. walter-bersch.de .

- ↑ The city of Boppard becomes the owner of the historic city walls along the B 9. July 23, 2013, accessed on October 8, 2013 .

- ↑ DschG or DSchPflG RP