Rhenish Slate Mountains

| Rhenish Slate Mountains | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| surface | 25,812.8 km² in Germany | ||

| Systematics according to | Handbook of the natural spatial structure of Germany | ||

| Greater region 1st order | Low mountain range threshold | ||

| Greater region 2nd order | 24, 25, 27–33, 344, 56 → Rheinisches Schiefergebirge |

||

| Natural area characteristics | |||

| Landscape type | Low mountain range ( basement , partly volcanically interspersed) | ||

| Highest peak | Großer Feldberg ( 880.9 m ) | ||

| Geographical location | |||

| Coordinates | 50 ° 21 '56 " N , 7 ° 36' 22.6" E | ||

|

|||

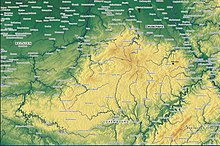

The Rhenish Slate Mountains are low mountain ranges in Germany (federal states of North Rhine-Westphalia , Rhineland-Palatinate , Hesse and Saarland ). As a geological - geographical unit, however, it extends to Luxembourg , France and Belgium and also includes the Ardennes . Its highest point is located on the right bank of the Rhine in the Taunus on the Großer Feldberg at 880.9 m above sea level. NHN and on the left bank of the Rhine in the Hunsrück with the Erbeskopf (816 m above sea level).

Surname

The name of the mountain goes back to Karl Georg von Raumer , who declared in 1815:

"The widespread clay slate gave the Rhenish Slate Mountains its name at the beginning of the 19th century, whereby the deposits in the Eifel played a decisive role: Here, slate prevails over all other rocks in our mountains, which I therefore name after him."

Geographical breakdown

overview

The Rhenish Slate Mountains as a Central to Western European natural landscape are divided into two parts by the Rhine . The almost butterfly-shaped mountains in the schematic map image (see right) are highly differentiated and are divided into the slate mountains on the left bank of the Rhine and the slate mountains on the right bank of the Rhine . Its mean height is about 500 m.

The Rhenish Slate Mountains are bounded in the west and south-west by the Paris Basin , in the south by the Saar-Nahe Basin , the Mainz Basin and the Wetterau . The eastern edge forms the Hessian depression belonging to the West Hessian mountainous region. On the northern edge, the Lower Rhine Plain , the Lower Rhine Bay and the Westphalian Bay are parts of the North German lowlands . To the north of the Ardennes lies the old Paleozoic Brabant massif, which is only exposed in the valleys of southern Brabant, under recent overburden .

The east wing of the Rhenish Slate Mountains is cut through by the Lahn . To the south of the Lahn lies the Taunus, to the north of it the Westerwald and the Gladenbacher Bergland with the Bottenhorn plateaus , to which the Siegerland connects to the north. The Sauerland as the center of the northeastern Slate Mountains with the Rothaargebirge as the core of the Hochsauerland merges to the west into the Bergisches Land . The easternmost tip is formed by the Kellerwald . The west wing of the Rhenish Slate Mountains is cut through by the Moselle , south of it lies the Hunsrück , north of it the Eifel and the Ardennes with the High Fens .

In addition to the three large valley furrows of the Rhine, Lahn and Moselle, two larger intramontane basins shape the landscape, the Middle Rhine basin between Koblenz and Andernach and the Limburg basin on both sides of the Lahn around Limburg . From the north, the Lower Rhine Bay encroaches far into the slate mountains along the Rhine, from the southwest the Trier Bay .

Mountain range

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Rhenish Slate Mountains (with objects in neighboring landscapes) : - Highest elevations of partial elevations and neighboring landscapes - Some river / estuary heights - Four largest reservoirs - Most important large cities Height data in meters (m) above sea level (NHN) |

Parts of the Rhenish Slate Mountains - with the respective maximum height of the most important landscapes in meters (m) above sea level and natural space main unit group ( italics ) - are these low mountain ranges :

|

Left of the Rhine |

Right of the Rhine

|

Flowing waters

The Rhenish Slate Mountains are traversed by these rivers , among others :

geology

The Rhenish Slate Mountains arose between 299 and 419 million years ago as part of the Variscan orogeny and lies in the so-called Rheno- Hercynian zone (also known as the Rheno-Hercynian zone). Its structure and geological development are closely related to the Harz Mountains in the east and the English coal basins in Devon , Cornwall and Pembrokeshire in the west. Except for very limited areas with older layers, its rocks mainly date from the Devonian and Carboniferous periods . At the edge, rocks from the Permian , Triassic , Jura and Cretaceous periods spill over onto the slate mountains. In the basins in the interior of the slate mountains and the Lower Rhine Bay, sediments from recent geological history ( palaeogen and neogen ) can be found to a large extent .

Particularly in the Eifel and Westerwald, volcanic rocks from the Palaeogene and the Neogene are common. In the Eifel, volcanism even lasted into historical times and cannot be regarded as completely extinct to this day.

rocks

The term slate mountains leads to the assumption that in the Rhenish slate mountains there is a particularly large amount of slate almost everywhere , but this is only true to a limited extent. “Pure” slate, the roofing slate popular as a building material , is only accessible in limited areas, such as B. in the Moselle area and on the lower reaches of the Rhine, in parts of the Bergisches Land or the Siegerland. The main mass of rocks in the slate mountains are slate sandy mudstones , sandstones , greywacke and Taunus quartzite .

In addition, in the northern Ardennes, in the Eifelkalkmulden and in the northern Eifel , on the northern edge of the eastern slate mountains, in the Bergisches Land and in the Sauerland as well as in the Lahn-Dill area, mass limestone from the Central Devonian with corresponding karst phenomena occurs to a large extent . Caves have often formed here, such as the Atta cave in Attendorn , the Balver cave and the Recken cave near Balve or the Kubacher crystal cave near Weilburg . The limestone is still an important raw material in these areas and is sometimes extracted in very large quarries. This applies above all to the northern mass limestone range from the Ardennes via the Eifel, Wülfrath , the Hönnetal and Warstein to Brilon . In the area of the middle Lahn, the so-called Lahn marble , a mass limestone that can be polished, is important.

Volcanic rocks such as basalt , tuff and pumice are more widespread in the Vulkaneifel , in the Siebengebirge and in the Westerwald ; they were deposited on the old hull of the slate mountains in the Palaeogene and Neogene. Volcanic rocks are also mined in the Lahn area; these come from the Devonian and Carboniferous and are much older than those from the Vulkaneifel, Westerwald and Siebengebirge. The large clay deposits of Kannenbäckerland are located in the vicinity of the Westerwald . Gravel and sand play only a subordinate role in the slate mountains, only significant deposits are preserved in the Middle Rhine Valley .

Geological structure

The Rhenish Slate Mountains comprise the following structural units from north to south:

- Namur-Synklinorium, Dinant-Synklinorium, Liège Revier, Aachener Revier with Inde- and Wurm-Mulde, Ruhr area (Molasse)

- Old Paleozoic of the Ardennes, Stavelot-Venn-Sattel, Remscheid-Altenaer Sattel, Ebbe-Sattel

- Eifel-Mulde, Eifler North-South Zone, Eifler Hauptsattel, Paffrather Mulde , Attendorn-Elsper Doppelmulde , Gummersbacher Mulde, Müsener Sattel, Ostsauerland Hauptsattel

- Siegener saddle

- Moselle Mulde, Dillmulde , Wittgensteiner Mulde, Hörre Zone , Kellerwald

- South Eifel, Hintertaunus, Lahnmulde , Hessian slate series, Gießen ceiling

- Hunsrück, Taunus

The Hunsrück-Taunus southern rim fault limits the Rhenish Slate Mountains on both sides of the Rhine. It is interpreted as a suture and represents the interface to the Saxothuringian .

Geological evolution

The rocks of the Rhenish Slate Mountains were deposited in an ocean that developed from the Lower Devonian. By stretching the passive continental margin of Laurussia ( Old-Red continent ), an ocean basin was created that initially deepened to the south, the southern margin of which was formed by a high area now south of the Moselle and the Sieg and then at least partially protruding from the ocean. From the Devonian to the beginning of the Upper Carboniferous , shallow deposits of marine sediments as well as clastic and carbonate sediments took place in this sea , but ultimately had a total thickness between 3 and 12 km. In addition - only regionally significant - there was the deposition of volcanic rocks.

In the extreme southern slate mountains in Hunsrück and Taunus, the renewed transition into the deeper ocean has been preserved. On the eastern edge of the slate mountains near Gießen , in the Gießen cover, on the rocks of the Rhenoherzynic, the remains of an oceanic basin that was formerly to the south lie. Its opening began with the lower Middle Devon , its complete closure is dated to the early Lower Carboniferous .

In the Lower Carboniferous the entire area was covered by the Variscan mountain formation . The deposited rocks were folded , tectonically scaled and pushed together to form a large-scale pile of ceilings . Parts of the slate mountains were subject to a metamorphosis that increased from north to south . Flysch rocks were deposited in front of the mountain formation moving northwards, and these are increasingly younger in age towards the north. The age of the metamorphosis, which can be determined by radiometric determination of the age of characteristic minerals , also decreases from around 340 to 320 million years in the south to around 305 to 290 million years in the north.

The end of the orogeny was accompanied by the formation of the north of the mountain located foredeep and the sedimentation of the Upper Carboniferous molasses with a clastic sequence with more than 100 coal seams . The Molassesedimentation sat in places up in the Lower Permian, as in smaller deposits in the ditch of Malmedy in Menden and in the Wittlich valley is documented. By the end of the Permian, the mountains were largely eroded and leveled into a lowland that barely protruded beyond the surrounding area. In addition to the rift-forming fracture structures, after the Variscan orogenesis numerous line-shaped fracture faults with SE-NW direction mostly running transversely to the fold structures emerged, which blocked the old mountains and where vein- shaped mineralization formed in numerous places .

Since the Permian, the Ardennes and Slate Mountains have essentially remained a land area. Marginal encroachments by various sea advances can mostly be detected on the edges of the mountains. The following areas show remnants of recent deposits:

- Zechstein sediments on the eastern edge of the Rhenish Slate Mountains

- Terrestrial deposits of the red sandstone and the Keuper as well as marine sediments of the shell limestone and the Lias (Lower Jura) in the Eifler north-south zone from the Trier Bay via the red sandstone deposits of Gerolstein (Oberbettinger Triasgraben) to the Mechernich Triassic triangle

- Remains of a sea advance in the Upper Chalk , which can be found on the northern edge of the slate mountains on the right bank of the Rhine and in further distribution in the Ardennes and Eifel

- Tertiary sediments are again more widespread in and around the slate mountains. During this time both the sinking of the Lower Rhine Bay with the deposits of several thousand meters of clays, silts, sands and lignite and the other tertiary basins in the interior of the mountains, as well as the main phase of volcanism in the Hocheifel, the Siebengebirge and the Westerwald.

In the Quaternary the Rhenish Slate Mountains slowly rose. The streams and rivers gradually cut their way into the originally flat undulating plain, forming the various hillside terraces that are still visible today and creating the present-day image of the slate mountains with deep valleys and plateau-like ridges. The last phase of volcanism in the East and West Eifel began around 500,000 years ago. The last volcanic eruptions were witnessed by Homo heidelbergensis (the ancestors of the Neanderthals ), who lived in this area for about 600,000 years. Remains of their Stone Age settlements and also parts of a skeleton were found in the Neuwied Basin directly under the mighty pumice ceilings, which have been passed down from the catastrophic eruptions of the Eastern Eifel volcanoes. Even today, numerous sourlings , hot springs and gas leaks testify to the dormant volcanic forces.

See also

literature

- Werner P. d´Hein: National Geopark Vulkanland Eifel. A nature and culture guide. Gaasterland Verlag, Düsseldorf 2006, ISBN 3-935873-15-8 .

- D. Fliegel : A geological profile through the Rhenish Slate Mountains . Cöln, 1909. (online edition dilibri Rhineland-Palatinate)

- Claus von Winterfeld, Ulf Bayer, Onno Oncken, Brita Lünenschloß, Jörn Springer: The western Rhenish Slate Mountains. In: Geosciences. 12, 1994, pp. 320-324. doi: 10.2312 / GEOWISSENSCHAFTEN.1994.12.320

- W. Meyer: Geology of the Eifel. Schweizerbart'sche Verlagbuchhandlung, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-510-65127-8 .

- E. Schmidt et al: Germany. Harms Handbook of Geography. 26th edition. Paul List Verlag, Munich 1975, ISBN 3-471-18803-7 .

- J.-D. Thews: Explanations for the geological overview map of Hessen 1: 300,000. (= Geol. Abhandlungen Hessen. Volume 96). Hessian State Office for Soil Research, Wiesbaden 1996, ISBN 3-89531-800-0 .

- R. Walter among other things: Geology of Central Europe. 5th edition. Schweizerbarth'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-510-65149-9 .

Web links

- Geological Service NRW , the former State Geological Office. official geological information source for North Rhine-Westphalia

- State Office for Geology and Mining Rhineland-Palatinate , official geological information source for Rhineland-Palatinate

- Hessian State Office for Environment and Geology , official geological information source for Hesse

- Literature on the Devonian of the Rhenish Slate Mountains. on vonloga.net

Individual evidence

- ^ Emil Meynen , Josef Schmithüsen : Handbook of the natural spatial structure of Germany . Federal Institute for Regional Studies, Remagen / Bad Godesberg 1953–1962 (9 deliveries in 8 books, updated map 1: 1,000,000 with main units 1960).

- ↑ Schmidt et al. 1975, p. 75.

- ↑ Werner Kasig: Biofacial and fine stratigraphic investigations in the Givetium and Frasnium on the northern edge of the Stavelot-Venn-Massif . 1975 (dissertation RWTH Aachen University).

- ↑ Schmidt et al. 1975, p. 80.

- ↑ Walter 1992, p. 168.

- ↑ Landscape history in the Ösling with an animated film on talent development , on webwalking.lu

- ↑ Walter 1992, p. 185.

- ↑ Meyer 1986, p. 477.

- ↑ Meyer 1986, p. 481.