Argentovaria

| Oedenburg-Altkirch fort | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Argentovaria |

| limes |

Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes (DIRL), Maxima Sequanorum |

| Dating (occupancy) | 370 AD to early 5th century |

| Type | Cohort fort? |

| unit | Limitanei / Foederati ? |

| size | approx. 93.30 m × 126 m (1.2 ha) |

| Construction | Stone construction |

| State of preservation | Not visible above ground, rectangular complex with 14 square corner and intermediate bastions. |

| place | Biesheim |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 2 '27 " N , 7 ° 32' 36" E |

| height | 194 m |

| Previous | Fort Sasbach-Jechtingen (north / right bank of the Rhine) |

| Subsequently | Mons Brisiacus (southeast / right bank of the Rhine) |

| Backwards | Horbourg Castle |

Argentovaria (also known by the field name Ödenburg ) is the collective term for a late Roman military installation and a civilian settlement in the area of Biesheim in Alsace ( canton Neuf-Brisach , Arrondissement Colmar-Ribeauvillé , Communauté de communes du Pays de Brisach ).

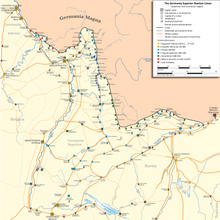

The ancient excavation sites of Biesheim-Kunheim and Ödenburg-Altkirch owe their special importance to their position at an important crossing over the Rhine. In the 1st and 4th centuries AD, the place was still dominated by the military, but in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, the civilian settlement came to the fore. During the great barbarian invasions in the 4th and 5th centuries AD, Argentovaria was probably part of a fortress belt that also included the forts on the right bank of the Rhine on the Münsterberg in Breisach and on the Sponeck in Sasbach-Jechtingen.

The late Roman castrum was probably one of the numerous border fortresses built under Emperor Valentinian I , but only briefly occupied, in the final phase of Roman rule over the Rhine provinces. It was part of the chain of fort of the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes in the section of the Maxima Sequanorum province . The camp was probably occupied from the 4th to the 5th century AD with Roman troops who were responsible for security and surveillance tasks on the Rhine border (ripa) .

Surname

The ancient name of the civil settlement and the fort are known to us from the geographer Claudius Ptolemaios and from the Tabula Peutingeriana . Inscriptions to prove this name have not yet been discovered. Around the year 150 called Ptolemy civil settlement Argentovaria next Augusta Raurica as the "second Polis " of the Celtic people of Rauriker . The current field name "Altkirch" (popularly "Kirchenbuckel") goes back to a church from the Middle Ages, which together with its cemetery could be located west of the south gate of the late antique fort.

location

Biesheim is about halfway between Basel and Strasbourg, north of Neuf-Brisach and exactly opposite the Kaiserstuhl mountain range . The mountain ranges of the Vosges and the Black Forest, in connection with the strongly meandering Rhine, were significant traffic-related obstacles and to this day only allow east-west passages in a few places. The late antique fort is located on the left bank of the Rhine, a little northwest of the Breisach fort . The archaeological sites are north of Biesheim. Maps from the 16th and 17th centuries show a place called Edenburg, Oedenburg or Oedenburgheim, which was destroyed in the Thirty Years' War and not rebuilt afterwards. The first wood-earth fort that can be identified here stood on an island on the Rhine, which offered good natural protection. The area of the late antique fort is used intensively for agriculture and is only recognizable today by means of a stepped terrain. The fortification was located directly to the east of the Limes Road (via puplica) , close to the demolition on what was then the banks of the Rhine, and was therefore easily accessible by land and also by ship. The findings indicated that as a result, the camp was hit by floods more frequently. Today only the Riedgraben Canal passes here, a sparse remnant of the ancient river bed. The border line between the two late antique Rhine provinces Germania I and Maxima Sequanorum ran north of the Kaiserstuhl . There was a road along this line that reached the banks of the Rhine at Biesheim-Oedenburg via the Vosges and Metz. Here it subsequently crossed with the Limesstrasse on the left bank of the Rhine, running from north to south. The fort probably had a strong connection to these road connections.

Research history

Ödenburg is mentioned for the first time by Beatus Rhenanus in 1551 and also appears on Daniel Specklin's map in 1576. Roman finds have been known since around 1770. Originally, Horbourg-Wihr, a district of the municipality of Horbourg near Colmar in the Alsatian department of Haut-Rhin, was regarded as the location of the ancient Argentovaria . However, this assumption had to be revised based on the latest research results. At the turn of the 1970s to the 1980s, scientifically accompanied excavations took place in the southern area of the medieval cemetery for the first time, whereby the area of the late antique fortress was also excavated, but this was not recognized as such. From 1998 to 2002 geophysical soil surveys were carried out as part of the trinational archeology project "Ödenburg-Altkirch" (Eucor program). After their evaluation, targeted exposures by scientists from the University of Freiburg and the University of Basel under the direction and coordination of Hans Ulrich Nuber and Michel Reddé ( University of Paris) became possible. The aim was to further supplement the knowledge about the ancient settlement of the area of Ödenburg-Altkirch (military camp, street praetorium, civil town and Gallo-Roman temple district) from the 1st to the 4th century AD. The excavations were also accompanied by paleobotanical and zoological studies. In the course of this, the late Roman fortifications and, in addition, a group of buildings at the same time in the adjacent corridor “Westergass” were recognized. By 2001 international excavation teams moved almost 1000 m² of earth and determined 470 findings, whereby the course of the north wall could be precisely determined. From 2003 to 2005, the École pratique des hautes études , together with the universities of Freiburg and Basel ( Peter-Andrew Schwarz , Caty Schucany) carried out excavations on the area of the Gallo-Roman temple district in Biesheim-Kunheim. Numerous new insights into ancient cult practices (modus munificendi) could be gained. In front of the fort, some ancient building remains of the civil town from the end of the 1st century AD, which had been destroyed by fire, could still be uncovered.

development

The region around Biesheim has been settled since pre-Roman times. Along with Kaiseraugst, Argentovaria was probably one of the largest oppida (caput civitatis) of the Rauriks . In order to keep this under control, the Romans first built a simple wood-earth fortification at this strategically important place. The Roman civil settlement did not develop around this early fort, but around the temple area from AD 20.

The wood and earth fort was founded in the 1st century AD, the late antique fort was probably built between 369 and 370 during the reign of Emperor Valentinian I (364–375) in the course of the last expansion and reinforcement measures on the Rhine Limes built. It belonged to a fortress belt (claustra / clausurae) , which consisted of the forts Breisach / Münsterberg (Mons Brisiacum) , Sasbach-Jechtingen, and Horbourg and presumably also included an Alemannic fortification on the Zähringer Burgberg.

The wood-earth forts of the 1st century could u. a. served as a stage station and deployment base for campaigns in the areas on the right bank of the Rhine. The job of the crew in Argentovare was probably the monitoring of road traffic, the control of shipping traffic on the river and the security service at the Rhine crossing. Other activities included the observation of the Barbaricum on the right bank of the Rhine, daily patrols and the transmission of messages and signals along the Limes.

In the years between 259 and 260, Alemannic tribes finally overran the Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes. Then they occupied the Dekumatenland , which had been under Roman rule for more than 200 years. After the so-called " Imperial Crisis of the 3rd Century ", the Romans were able to stabilize the border along the Rhine, Lake Constance, Iller and Danube lines again. From the late 3rd century onwards, under the emperors Diocletian and Maximian , the chain of castles of the so-called Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes was built here. Nevertheless, the Alemanni repeatedly break into the territory of the empire because they often benefited from the internal power struggles of the Romans, which were usually associated with an almost complete withdrawal of the Limes troops.

In 357 AD the Battle of Argentoratum took place near what is now Strasbourg , in which Emperor Julian Apostata succeeded in routing the Alemanni and taking their King Chnodomar prisoner. In 378, allegedly 40,000 Alemannic Lentiens broke through - either directly at the Sponeck crossing or near Breisach - but again the Rhine Limes, devastated the border areas and penetrated into the interior of Gaul. The emperor of the western part of the empire , Gratian , had to order back a large part of his army, which was already in Illyria and which had been marched together with the emperor of the east , Valens , to fight against the Goths and Alans who had invaded Thrace. The attackers were soon thrown back across the Rhine by Gratian and his Frankish military leaders, the comes Nannienus and the comes domesticorum Mallobaudes , after a battle near Argentovaria , but this victory cost Valens dearly, since Gratian arrived too late in the Balkans, to save his uncle from the catastrophic defeat at Adrianople . In August 369, Emperor Valentinian I was demonstrably staying in the neighboring fort on Mons Brisiacum in order to coordinate and monitor the large-scale construction activities of the Romans on the Rhine Limes, at least temporarily. In the course of this, the fortress in Argentovaria was built . Judging by the series of coins, it existed until the withdrawal of the regular border troops under Stilicho between 401 and 406 AD, and possibly even until the middle of the 5th century AD.

The castle ruins were probably still visible above ground until the end of the 17th century. From 1701 it was removed to extract stone material for the construction of the Neuf-Brisach fortress .

Fort

A Roman military base had existed in Biesheim since the 1st century AD. Altogether, two Julian-Claudian wood and earth forts were found for this period, but they were abandoned again in the late 1st century. Hans Ulrich Nuber suspects another predecessor building from the time of Augustus under the late antique fort .

Oedenburg-Altkirch represents a new type of fort within the broad late antique fortress construction program. The Valentine castrum measured 93.30 m × 126 m, was precisely aligned with the cardinal points, had a square floor plan and covered an area of approx. 1.2 ha The building material consisted for the most part of volcanic rock (so-called tephrites) found in the area. The Roman unit of measurement used in the construction could be determined on the basis of still intact, mortared brick plates. It was exactly 66 cm and thus corresponded to two Gallic pedes Drusani (approx. 0.3327 meters). The unusual construction of this camp resembles a - albeit much smaller (65 m × 56 m) - facility of the same time in Trier-Pfalzl, which has been known as the palatiolum since the Middle Ages . There are clear indications that it was furnished with magnificent interior decoration (e.g. mosaics) and thus could have had a representative function above all. Such findings are missing for Oedenburg-Altkirch, but it could have been planned by the same architect.

Enclosure

The three meter wide, carefully laid out and mortared circular wall was reinforced with fourteen square bastions, four on the long sides and three on the narrow sides, the dimensions of which were almost identical for each specimen. The masonry was partially preserved up to a height of 1.33 to 1.74 meters. The foundations sat on rammed wooden piles that reached 0.50 meters into the masonry, which were reinforced at the edge with rectangular beams, connected by crossbars. The grating was filled with layers of rubble that had been poured with lime mortar. The partition walls, on the other hand, were also based on a bed of lime mortar reinforced with beams. These foundations were first observed on watchtowers in Switzerland, which date back to 371. The southwest corner was severely disturbed by a bunker on the Maginot Line . The outer façade, presumably up to 24 m high, had an impressive depth staggering due to the - about five meters - protruding and 14 meters wide, tower-like bastions. The corner bastions were created by continuing and superimposing the respective lines of space. As a result, two square tower bastions had formed at an angle of 90 degrees, which were the same size as the central specimens. The inner chambers had a side length of 7.50 m. They went into niche rooms half as large, the entrances of which were vaulted by arches supported on pillars. Together with these they reached an area of 120 m².

To a viewer standing in front of the fort, the walls appeared to be considerably higher than they actually were. Bastions and crew barracks were possibly covered with tiled roofs. The camp was also protected in the north and south by a weir ditch (north section: 8.20 meters wide and 1.80 m deep, south section: 6.50 meters wide and 2.30 meters deep). The northern one could be crossed by an earth dam, while the southern one ran through and was probably spanned by a bridge. The berm was about 10 m wide.

Gates

A total of two gate systems were found. These structures - facing north and south - are so-called chamber gates . They had two passages and were located in the central tower bastions on the narrow sides. When the north gate was excavated in 2000, u. a. its width, 14 m, can also be determined. Like the corner bastions, it protruded about 5.08 m from the wall. The passages were three meters wide. The access from the outside - as with other late antique gates - was probably closed by two wooden door leaves and a portcullis. The tower foundation pulled through here and was supposed to accommodate the portcullis after it was lowered. At the exit to the inner courtyard, the inner chamber was divided by a central column (spina) with a side length of 1.50 m, which could also be closed by two wooden gate wings. The inner chamber of the gate measured 13.14 mx 7.98 m. The side walls reached a length of 21.31 m. The south gate, however, could no longer be recorded in its entirety. The passage was designed a little differently, perhaps due to different values. From here you had direct access to the river bank and the Limes road. In 2003, an angular wall was discovered on the eastern gate cheek, which presumably had a counterpart on the western side, possibly the remains of an interior portico.

Indoor

The interior development consisted of casemate-like , multi-storey installations that were lined up along the curtains and divided into ten blocks, each with four 7.5 x 5.5 m rooms. They were of different sizes on the western wall, presumably they served a different purpose. No canopies (portico), which were often observed in comparable forts, could be found in the crew quarters. The inner courtyard initially seemed to have been kept free of any development, but in 2002 the remains of a rectangular building, which probably dates from the 1st century AD, were discovered south of the north gate. After the Roman occupation left, some simple pit houses and wooden frame structures were built here. The medieval churches once stood in the southwest corner, of which two apses can still be identified.

garrison

The late antique occupation unit of Argentovare is not known, only the legio I Martia is documented in the first half of the 4th century as the border protection force responsible for the section on the Upper Rhine. The camp was probably - as usual for the 4th and 5th centuries - occupied with Limitanei / Ripenses or - due to its time position even more likely - with Germanic Foederati (allies), who belonged to the army of the Dux provinciae Sequanicae . One of the most important ancient sources for the assignment of border troops and forts of the 4th and 5th centuries is the Notitia Dignitatum . In it, however, neither the fort name nor the garrison unit or its commanding officer are given. The discovery of a siliqua from the time of Constantius III. (408–411), could be a vague indication that it was reoccupied after the devastating incursion of the Vandals and Suebi in 406 .

Civil settlement

The settlement had a small town character and stretched over an area of 200 hectares. At its heyday it probably had around 5,000 inhabitants. The distribution of the buildings was to a large extent influenced by the topographical conditions at the time. The Rhine valley at that time was characterized by many smaller watercourses and extensive swamp areas. These often prevented coherent development, which is why the houses almost exclusively had to be built on the somewhat higher gravel terraces. Some of these could also be reached via artificially created channels. It was still inhabited even after the withdrawal of the military under the Flavian emperors. The core of the settlement was in the area of the late antique castrum. The streets were laid out like a grid. The place had a well-developed infrastructure, which included two thermal baths, a large public building complex ( mansio ?), A mithraeum , a Rhine harbor and the Gallo-Roman temple district. Many of the houses were decorated with wall paintings, which testifies to a certain wealth of its citizens. The older foundations were made of basalt, the later ones lay on a layer of river pebbles. Some areas of the city may have been abandoned as early as the 1st century AD, but some new buildings were added in the west of the area in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. A development in the tetrarchy or in the subsequent period could not be determined. In the course of the 5th century, the city was finally destroyed due to the rapidly advancing land grabbing by barbarian tribes. Its ruins were almost completely removed by stone robbery in the following centuries (including for the construction of the Vauban Fortress Neuf-Brisach).

Street praetorium / mansio and thermal baths

The building complex of the late antique Praetorium (II) consisted of two buildings (hostel / Praetorium and bathing building / Thermae) and was located on the "Westergass" corridor, 90 m east of Limesstrasse. The main building was oriented towards the main road and was largely surrounded by a pointed ditch with a gate passage. It covered an area of 24 m × 29 m, the much smaller thermal bath one of 7 m × 14 m. Both were covered with a tiled roof, the roof tiles had been supplied by the Legio I Martia from Kaiseraugst. A fountain shaft was subsequently discovered in front of the praetorium . Post-Roman use is documented by the observation of post holes. They come from half-timbered buildings that replaced the Roman buildings in the early Middle Ages. Praetorium and Therme probably originated in the period between the rule of Constantine I, or his sons and Valentinian I (330 to 340 AD). They were in use until the 5th century. In their final phase, the buildings are likely to have made a neglected and run-down impression, as the residents u. a. disposed of their waste immediately in front of the entrances. The buildings probably served as a road and rest station (mansio) for state officials in transit, soldiers and couriers of the Reich administration.

Temple precinct

The 1.4 hectare multi-phase temple district in the Biesheim-Kunheim corridor, excavated from 2003 to 2005, consisted of four so-called handling temples (buildings A, B, E, C) and ten other cult buildings, all of which were built in the 1st century AD. Were created. It covered an area of around 1.6 hectares, making it one of the largest of its kind in this region. It may have been built over an even older Celtic sanctuary, as the area was surrounded by swamps and an arm of the Rhine in ancient times. The Celts preferred these topographical features when setting up their holy sites, as they needed bogs and lakes to sink their offerings. The first wood and clay buildings date from the years between 70 and 110 AD, they were replaced by stone buildings in the 2nd and early 3rd centuries AD. One of them was surrounded by a 14 × 14 m colonnade. Its foundations are only very poorly preserved through centuries of agricultural activities. The numerous militaria finds in Temple B show that it was mainly visited by soldiers. This stone temple, uncovered by Basel archaeologists, was probably built by members of Legio VIII Augusta from Strasbourg / Argentorate , as evidenced by the brick temple . Subsequently, there were also numerous burnt offerings, altars for coin offerings and a sanctuary for the gods Apollo and Mercury, which could be identified by an inscription.

Mithraeum

The Mithraeum , which was examined between 1976 and 1979, stood east of the city and was used to worship the Persian god of light Mithras , whose cult was particularly popular among soldiers. The building had a long rectangular floor plan, was oriented to the north and consisted of two cult rooms and a vestibule ( pronaos ). The slightly lower interior could be entered via two steps. On both sides of the first room there were brick benches that were used by the believers at the cult meal. In the exedra at the north end of the building there were still some limestone fragments of a relief that showed the deity killing a bull (tauroctonus) . The Mithraeum in Biesheim probably belongs to the purely civil phase of the settlement after the withdrawal of the garrison around 70 AD. According to the coin finds, the sanctuary was destroyed at the end of the 4th century AD.

Finds

In the southern section of the moat of the fort there were not only late Roman ceramics but also a coin from the time of Valentinian II (378–383 AD). The finds at the street praetorium II consisted mainly of Roman and Germanic clothing components that could be recovered from several pits.

The finds of oysters and fish from the Mediterranean as well as the remains of a bottle gourd from Africa, which is one of the oldest artifacts of its kind in Europe, speak for the far-reaching trade relations of the inhabitants of Argentovaria . The peppercorns found in the civil town are also particularly noteworthy.

In the temple area there were mainly coins, fibulae, militaria such as lance shoes, shield humps, some helmet cheek flaps ( Weisenau type ) etc. and objects made of lead, which were probably brought here as offerings. Fragments of - partly gilded - objects, furniture and door fittings, large bronzes, a bronze lamp, fragments of a limestone statue and an inscription by Titus Silius Lucusta, dedicated to Apollo , showed that the temple inventory must have been very lavishly furnished. There were also isolated pits around the temples that still contained fragments of amphorae. They served as places of worship (stipa) for coin offerings. Eggshell fragments suggest that organic offerings were also kept in them. 184 ceramic vessels (jugs, bottles) and objects (e.g. candlesticks, lamps) of various designs were recovered from stone temple D. For the sacrificial ceremony, they had obviously been filled with wine and beer beforehand, then placed on a fur-covered elm frame or a stake and then burned.

The finds from the excavations are kept in the Musée Gallo-Romain in Biesheim. Various items of equipment exhibited here prove the presence of soldiers. Numerous items also provide clues about daily life. A gem set in gold is the most important piece in the collection. The burial customs are presented using reconstructed graves.

Monument protection

The facilities are ground monuments within the meaning of the French Monument Protection Act ( Code du patrimoine ). Archaeological sites - objects, buildings, areas - are defined as cultural treasures ( monument historique ). Robbery excavations must be reported immediately. Probing in protected areas and unannounced excavations are prohibited. The attempt to illegally export archaeological finds from France will result in at least two years imprisonment and 450,000 euros, willful destruction and damage to monuments will result in up to three years imprisonment and a fine of up to 45,000 euros. Archeological finds made by chance are to be handed in immediately to the responsible authorities.

See also

List of forts in the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes

literature

- Hans Ulrich Nuber, Michel Reddé: Oedenburg. Rapport de la Campagne préliminaire menée en 1998 à Biesheim-Kunheim et program triennal 1999-2001. 2 volumes. Paris 1999.

- Hans Ulrich Nuber, Michel Reddé: Les Fouilles sur le site militaire Romain d'Oedenburg: premiers résultats. In: Annuaire de la Societé d'Histoire de la Hardt et du Ried 12, 1999, pp. 5-14.

- Lothar Bakker: Bulwark against the barbarians. Late Roman border defense on the Rhine and Danube. In: Karlheinz Fuchs, Martin Kempa, Rainer Redies: The Alamannen . 4th edition. Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8062-1535-9 , pp. 111-118.

- Suzanne Ploin (Ed.): La frontière romaine sur le Rhin Supérieur. A propos des fouilles récentes de Biesheim-Kunheim, catalog d'exposition. Musée Gallo-romain de Biesheim, Biesheim 2001.

- Hans Ulrich Nuber, Michel Reddé a. a .: The Roman Oedenburg. Le site militaire romain d'Oedenburg (Biesheim-Kunheim, Haut-Rhin, France), Premiers résultats. In: Germania 80, 2002, pp. 169-242.

- Hans Ulrich Nuber: Late Roman fortresses on the Upper Rhine . In: Freiburg University Gazette. 159, 2003, pp. 93-107.

- Hans Ulrich Nuber: The late Roman fortress Oedenburg (Biesheim / Kunheim, Haut-Rhin, France) and its function in the border area between Germania I and Sequania . In: Limes XIX. Proceedings of the XIXth International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies in Pécs, Hungary Sept. 2003. Pécs 2005, pp. 763-771.

- Hans Ulrich Nuber: The late Roman military zone on the southern Upper Rhine and the fortress in Oedenburg . In: Archäologische Nachrichten aus Baden 70, 2005, pp. 43–48.

- Gabriele Seitz, Peter-Andrew Schwarz, Caty Schucany, Jörg Schibler, Stefanie Jacomet, Hans Ulrich Nuber, Michel Reddé: Oedenburg. Une agglomération d'époque romaine sur le Rhin supérieur. Fouilles françaises, allemandes et suisses à Biesheim-Kunheim (Haut-Rhin). In: Gallia 62, 2005, pp. 215-277 digitized .

- Gabriele Seitz, Marcus Zagermann: Late Roman fortresses on the Upper Rhine. In: Badisches Landesmuseum (ed.): Imperium Romanum - Romans, Christians, Alamannen - The Late Antiquity on the Upper Rhine: Exhibition catalog for the state exhibition in the Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe from October 22, 2005 to February 26, 2006. Theiss, Stuttgart 2005.

- Hans Ulrich Nuber: Between the Vosges and the Black Forest: the region around Brisiacum / Breisach and Argentovaria / Oedenburg in late antiquity. In: Michel Kasprzyk, Gertrud Kuhnle (eds.): L'Antiquité tardive dans l'Est de la Gaule I. Dijon 2011, pp. 223–245 (Revue Archéologique de l'Est, Suppl. 30)

- Michel Reddé (Ed.): Oedenburg. Fouilles françaises, allemandes et suisses à Biesheim et Kunheim, Haut-Rhin, France. Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum, Mainz

- Part 1; Hans-Georg Bartel: Les camps militaires Julio-Claudiens. 2009. ISBN 978-3-88467-132-0 .

- Volume 2: L'agglomération civile et les sanctuaires. 2011. ISBN 978-3-88467-189-4 .

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Ptolemy 2: 9; Tabula Peutingeriana, Segmentum 2, 4.

- ↑ Seitz / Zagermann 2005, pp. 204–205; Nuber 2005, p. 764.

- ↑ Seitz / Zagermann 2005, p. 204.

- ↑ Marcus Zagermann: The Breisacher Münsterberg. The fortification of the mountain in late Roman times. In: Heiko Steuer, Volker Bierbrauer (Ed.): Hill settlements between antiquity and the Middle Ages from the Ardennes to the Adriatic. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-020235-9 , pp. 165-185.

- ^ Matthias Becher: Chlodwig I. The rise of the Merovingians and the end of the ancient world , Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978 3 406 61370 8 , p. 63.

- ↑ Seitz / Zagermann 2005, pp. 204–205.

- ↑ Seitz / Zagermann 2005, p. 204, Nuber 2005, p. 766–767.

- ↑ a b Nuber 2005, p. 765.

- ↑ Nuber 2005, p. 766.

- ↑ Nuber, Seitz 2001.

- ↑ Seitz / Zagermann 2005, pp. 206–207.