Tasgetium

| Eschenz Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Tasgetium |

| limes |

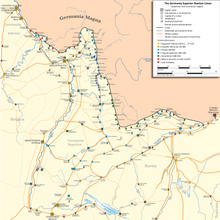

Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes , route 3 |

| section | Maxima Sequanorum or Raetia I , the borderline at that time is unclear. |

| Dating (occupancy) | Diocletian, before / around 293 to 305 AD up to max. before / around AD 420 |

| Type | Cohort fort? |

| unit | unknown |

| size | 88 m × 91 m = 0.8 ha |

| Construction | Stone fort |

| State of preservation | Diamond-shaped fortification with polygonal and semicircular towers, still visible above ground |

| place | Eschenz and Stein am Rhein |

| Geographical location | 706 679 / 279390 |

| Previous | Fort Konstanz ( Constantia ) (southwest) |

| Subsequently | Fort Pfyn ( Ad fines ) (southeast) |

Tasgetium is the collective term for a late Roman border fort of the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes , a bridgehead fort, as well as a civil settlement from the high imperial period and late antique . They are located in the municipality of Eschenz (Vor der Brugg district), Frauenfeld district , Canton Thurgau and in Stein am Rhein (St. Georgs Kloster), Canton Schaffhausen , Switzerland .

A civil settlement of the same name had existed since the 1st century, it stretched along a Roman road 500 meters east of the fort in Eschenz. Archaeological finds as well as a fragmentary building inscription show that the Romans built a fort on the left bank of the Rhine in the beginning of late antiquity , the garrison of which secured an important river crossing there. To the right of the Rhine there was also a small fortified bridgehead fort. A late Roman cemetery was also discovered during excavations. A certain continuity of settlement can be proven up to the Middle Ages; several medieval buildings were built on the foundations of Roman structures. Today the Johanneskirche stands in the center of the fort area. Due to the rich finds around the fort, later also on the right bank of the Rhine in the St. Georg monastery, Eschenz and Stein am Rhein are among the archaeologically most important ancient sites in Switzerland.

Surname

Tasgetius / Tazgetios was originally a man's name, which, according to Julius Caesar, was in use among others among the Gallic tribe of the Carnutes . According to some researchers, the ancient place name Tasg (a) etium was taken over by the Romans from the Celtic predecessor settlement, which may have been founded by a man named Tasgo or referred to the local possessions of Tasgetios. The Romans only replaced the Celtic ending with the Latin suffix -ium. The Roman name of the place was later forgotten. The term "castle" for the Castle Hill since the time of Emperor I. Otto occupied.

location

The late antique fort is located on the left bank of the Rhine on an elevation (Auf Burg) on the south bank of the outflow of the Untersee (Lake Constance). In ancient times there was the border of the Roman province of Maxima Sequanorum , which emerged from the Germania superior (Upper Germany) around 297 AD . The exact course of the border to Raetia I is unknown. Tasgetium was probably still on Raetian territory, the border between Zurich and Walensee ran in the south. The line Basel - St. Margrethen formed the imperial border twice in Roman times: in the 1st century AD until the conquest of the Dekumatland and from around 260 until the beginning of the 5th century.

Road link

The Roman road, known in literature as the “ Rhaetian border road”, led from Tasgetium via Rielasingen , Singen , Friedingen , Steißlingen , Orsingen , Vilsingen , Inzigkofen to Laiz to a ford through the Danubius ( Danube ). In Orsingen there was a branch to Pfullendorf and Burgweiler . In the area of the Dürren Ast there is a junction via Schweingruben and the Ablachtal to Meßkirch , Krauchenwies and Mengen - Ennetach .

Research history

The fort in Eschenz has been known for a long time. The finds of inscriptions and the remains of bridges in the lake bed aroused the interest of scholars from the 16th century. In 1548 the "... old fort at Burg bei Stein ..." was mentioned in the Stumpf Chronicle . The first archaeological research began in 1741 when a dedicatory inscription for the river god Rhenus was discovered in the interior of the fort during the construction of the cemetery wall . In the 16th century the fragmentary building inscription of the fort was also found in the Johanneskirche, which dates it and which was interpreted by Theodor Mommsen in 1850. The remains of the Roman bridge near Eschenz were entered on plans in the 18th century, and the numerous coin finds from the bed of the Rhine near the bridges were also worth mentioning again and again. In the area of the civil settlement, excavations by employees of the Rosgarten Museum did not begin until the late 19th century. The excavations carried out by Bernhard Schenk in the thermal baths of the civil settlement on Dienerwiese in 1874/1875 attracted a great deal of attention . Even more important was the discovery of a stone inscription with the letters "TASG", which revealed the ancient place name Tasgetium to the researchers , which was not, as mistakenly assumed, Gaunodurum .

From the middle of the 20th century onwards, the fort walls, some of which were still visible, and their interior areas were also examined archaeologically. Mostly it was urban development changes that the archaeologists used for emergency excavations on site. As a result, most of the forts in the vicinity of Eschenz could soon be located, such as Brigantium (Bregenz) and Arbor Felix (Arbon). In Constantia (Konstanz) this only succeeded in 2003. In Tasgetium (Stein am Rhein) and Ad Fines (Pfyn), on the other hand, remnants of walls still visible above ground indicated where the former forts had stood.

In the years 1931 to 1935, the first Thurgau canton archaeologist Karl Keller-Tarnuzzer (1891-1973), supported by Archbishop Raymund Netzhammer (1862-1945), carried out extensive excavations on the island of Werd, where numerous remains of pile dwellings from the Jungstein and Bronze Age were discovered. During these investigations, however, Roman finds came to light. The art historian Hildegard Urner-Astholz (1905–2001), who lived in the parsonage of the Johanneskirche in Burg, accompanied some emergency excavations and published a summary of the results in 1942, which for a long time remained the only description of the Roman vicus. Equally important were the field observations by Alfons Diener (1923–2006), who from 1960 monitored all construction projects such as pipeline trenches, excavations and other soil encroachments and was able to recover countless objects and thus save them from destruction or disappearance. Willful damage, such as the tearing of Roman bridge piles at the beginning of the 1970s, affected the sites. It was only after Jost Bürgi was appointed cantonal archaeologist in 1973 that it was possible to better document the finds and findings that had come to light during the building projects and to gradually develop effective preventive measures for the preservation of the ancient remains. Between 1971 and 1987, the cantonal archeology department of Schaffhausen undertook extensive excavations in the former late Roman fort at Burg. In 1983 the Association for Village History was founded, which in 1991 set up a museum in the converted property "Blauer Aff".

After 2000, excavation work focused on the Eschenz region (Unter-Eschenz). During the excavation campaigns between 2005 and 2006, the area near the Vitus Church, which was demolished in 1738, was examined. Under the graves there were also layers from Roman times, for the most part in very moist soil. This is why organic materials, such as wood, had become attached to the north wall of the St. Vitus cemetery over the centuries. B. Timber of houses and parts of paths or water channels from the first two centuries AD are very well preserved. Their exact dating was possible through the annual ring analysis . Other materials such as animal bones and vegetable waste allowed conclusions to be drawn about the eating habits of the residents. In addition to countless ceramic shards, objects of daily use made of leather and even textiles could be recovered. This moist soil conservation makes Eschenz one of the most important sources north of the Alps for Roman everyday objects made of perishable materials. In 2009, examinations by divers took place in Gewann Orkopf near Badi Eschenz. In order to be able to precisely measure the floor plan of the Vicustherme again, but also to supplement the well-known building structures of Tasgetium, the Thurgau Archeology Office carried out a geophysical survey on the Dienerwiese in autumn 2010 .

development

Neolithic buildings testify to the very early settlement of the island of Werd and the nearby lake shore. From that time on, the area was continuously populated. Accordingly, numerous remarkable finds were made, some of supraregional importance. Among them are the famous gold cup by Eschenz (made in 2000 BC) and a Gallo-Roman wooden figure (60–70 AD).

Shortly before the turn of the century, the Romans advanced as far as the Untersee . In the course of the Alpine campaign of Augustus around the year 15 BC The area around Lacus Brigantius ( Lake Constance ) , which was ruled by the Celts, was also subjugated by Roman troops and later partly added to the newly established province of Raetia ( Raetia ). The Romans used the favorable natural conditions of shallow water zones and the Werd Islands , a small group of islands at the outflow of the Rhine from the Untersee, to open up an important north-south connection there. This was accessed via the large military road between Ad Fines ( Pfyn ) and Vitudurum ( Oberwinterthur ) and also served commercial traffic.

As the numerous finds from the early imperial period suggest, there was a fort in Stein am Rhein perhaps as early as the Augustan period. A first wooden Pfahljoch bridge was probably built over the lake between 50 and 82 AD (depending on the date of the annual ring). The top of the three Werd Islands in the middle of the Rhine served as an abutment. This opened a north-south connection that could be used all year round, giving trade a great boost. At the southern bridgehead an unpaved street settlement was built.

As a bridge and port, the vicus Tasgetium was at that time probably the most important Roman settlement in the area of today's Thurgau and had the only Rhine bridge within a radius of about 30 kilometers. It soon developed into a flourishing street settlement with numerous handicraft businesses and its own market. Since the border troops could no longer guarantee security since the 3rd century due to internal conflicts, the inhabitants of the border regions were forced to fortify their settlements due to repeated raids by plundering Germanic tribes . The waterline of the Rhine, Lake Constance, Danube and Iller formed a natural border. From the late 3rd century onwards, after the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes had been abandoned, it was secured with newly built watchtowers and forts ( Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes ). But the provincial residents also had to defend their settlements with walls far in the hinterland, such as in Pfyn, Oberwinterthur or Kloten .

The construction of the fort near Stein am Rhein at the end of the 3rd century should be seen in this context. The period of rapid changes of rulers and constantly flaring up civil wars (so-called imperial crisis of the 3rd century ) was ended for the time being under Emperor Diocletian . This then again worked hard to secure and strengthen the borders. From 293 he led the Roman Empire in dual rule with Maximian ( Augusti ), supported by two lower emperors ( Caesares ). Because of the threat from Alemanni raids , a fort was built between 293 and 305 AD on the castle hill on the left bank of the Rhine in what is now the “Vor der Brugg” district. This is evidenced by the largely preserved building inscription. The fortress was part of a new Roman border line along the Upper Rhine. This chain of fortifications, known in research as the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes, was an important section of the Roman imperial border in the 4th century AD to control border traffic and to ward off Germanic looters. Caesar Constantius Chlorus , who is responsible for Gaul and the Rhine border, was probably responsible for the construction of the fort . After its completion, the focus of the civilian settlement shifted to the west. The settlement from the Middle Imperial period was abandoned and a new vicus was built under the protection of the fortress. Finds suggest that some of the buildings of the mid-imperial vicus were still in use until the 4th century. A new stone bridge was built over the Rhine a little below the fort hill. It was additionally secured on the right bank of the Rhine by a fortified bridgehead and connected Tasgetium with the north bank and the forts in Constantia ( Constance ), Arbor Felix ( Arbon ) and Brigantium ( Bregenz ).

Shortly after 400 the fortress was renewed and strengthened, but perhaps with the temporary collapse of the Rhine border in 406/407 the fort could have been evacuated by its occupants. However, a further use up to the middle of the 5th century is also conceivable; the tearing down of the series of coins around 400 could also be explained by the fact that the limitanei in the 5th century were often rewarded in kind instead of money. It is not known exactly when the Roman border defense on the Raetian part of the DIRL was dissolved. By the end of the 5th century at the latest, however, the last regular soldiers, who probably no longer received any pay from the Western Roman government in Ravenna, should have withdrawn and left the fort to the now largely defenseless civilian population: this is the process for the forts on the Upper Danube expressly attested. Soon afterwards, the Alemanni took control of the region around Tasgetium and also occupied the fort. As a result, the immigration of Alemannic tribal associations to the Lake Constance area increased. A few grave finds from the 6th century in Eschenz and Stein am Rhein bear witness to this phase of immigration. During the excavations in the ruins, the remains of a first simple church building from the middle of the 6th century were observed: a wooden church was apparently built inside the Roman fort ruins before 600 AD. In the early 7th century, a stone sacred building was built as a separate church and monumental grave of an Alemannic aristocratic family (first mentioned in 799), which was called "on the castle" because of its location.

Fort

The inscription found under the floor of St. John's Church means that the fort can be dated to the time of Emperor Diocletian and the Tetrarchy (293 to 305). In addition, it could be narrowed down by a coin found in a wooden building, which indicates that construction began in the years 300/301. Since subsequent modifications could be seen on numerous buildings inside the fort, the Horreum probably did not originate from Diocletian times. According to the coin series, the fort was occupied by regular Roman soldiers ( limitanei ) at least until the beginning of the 5th century .

The fortress had a rhomboid ground plan, slightly shifted to the southeast, with sides of about 88 × 91 meters. The floor plan of the fortification can still be clearly seen from the wall foundations next to the Johanneskirche, which were restored in 1900 and 1911. With an area of only 7,900 square meters, it was comparatively small even by late antiquity. There was a polygonal tower at each corner. One of these towers was equipped with an angled passage as a slip gate. The gates were each flanked by two horseshoe towers on the east and west sides. Four specimens stood on the south side, two of which reinforced the 3.60 m wide main gate ( porta praetoria ). No towers could be found on the north side. Parts of the south and east walls are still upright. The remains of the southern outer wall today form, among other things, the boundary of the cemetery and are still clearly visible and preserved. The north wall, which bordered a steep slope to the Rhine, had only a small wall thickness (1.80 m) and was thus the weakest part of the fortification; apparently no attacks were expected from this side. The remaining sections of the fort wall were 2.80 m wide. The fort is likely to have been additionally secured on the south, east and west sides by a system of ditches with a palisade in front, the exact position of which is still unclear. The fort was secured by a ditch on three sides, except on the banks of the Rhine. In it, pointed oak stakes hammered into the west side could be detected as obstacles to approach. The wood for this was felled in the winter of 401/402 AD (according to the tree ring dating). At this time the fortress was probably still manned.

Interior development : The interior area was divided into four parts by the two main streets of the camp, via praetoria and via principalis . The former was paved with stone slabs. Little is known of the other buildings inside the fort, as they mainly consisted of perishable material. At the intersection of the two main streets of the camp there was a square building, possibly the former principia cum praetorio (staff building with accommodation for the camp commandant). In the west, only small-scale wooden and half-timbered buildings must have stood, with wattle walls on sill beams, mortar floors and hearths. After a fire, they were replaced by simple post structures.

During the excavations in the northeast corner, the remains of a hall-like building ( horreum ?) Came to light. Only a small part of a 0.65 m wide wall had survived from it. It ran parallel to the north wall of the fort. It is possible that this was the south wall of the building and that, similar to the Schaan Fort , the fort wall formed the north end. The distance of a little more than 10 m in width would be quite conceivable. Two stone extensions were observed on the wall. Markus Höneisen therefore interpreted the wall as the north wall of the building, which was equipped with pillar attachments on the inside. In this case, it was not a question of buttresses, but rather "supports of a heavily loaded intermediate floor". This assumption is supported by the fact that the pillars were not made in one piece with the wall, but were added separately. The western of these pillars was a sandstone slab, the eastern one a limestone block. According to Höneisen, the construction is comparable to the horrea in Trier, in which stud constructions for a mezzanine were also attached to the foundation templates . The building may have served as a weapons or clothing store. It is unlikely to be used as a grain store, as it would have to be equipped with a floating floor, of which no traces could be observed within the excavated area. To be able to draw clear conclusions, however, too little of the building was preserved.

garrison

Which units of the Roman army were stationed in the fort is unknown due to a lack of written sources. Presumably they were members of the Limitanei or Riparenses (border or bank guards) who were under the command of a Dux limites ( Dux Raetiae or Dux provinciae Sequanicae ).

Bridgehead fort and Rhine bridge

In 1986, under the medieval monastery of St. Georgen in Stein am Rhein on the right bank of the Rhine, mighty Roman wall foundations were found, which can be expanded to form a square floor plan with a side length of at least 38 meters (western wall). They belonged to the late antique bridgehead fort, which was built at the same time as the Tasgetium fort to secure the crossing of the Rhine.

In the 18th century there were reports of the remains of a then still visible wooden bridge that led from Unter-Eschenz over the eastern tip of the island of Werd to the opposite side of the Rhine to Arach. Other finds, especially a large number of ancient coins, indicated the existence of a Roman Rhine crossing even then. The erection of the first Roman Rhine bridge could be proven for the years 81/82 on the basis of dendrochronological investigations on wooden piles found on site. The timbers did not come from just one, but from several successive bridge structures. The Rhine crossing had been renewed several times during the settlement of Tasgetium. It connected the southern and northern banks of the Rhine via the eastern tip of the island of Werd . At this point the Rhine is wider, but the current is less strong there, which is particularly advantageous for a ship bridge. It was a 217 meter long pile yoke bridge with a yoke spacing of 15 and a width of 6.4 meters. Ten support piles with a diameter of 30 to 45 centimeters were driven into the river bed under each yoke. The subsequent section between the island of Werd and Arach was 220 meters long. Since no pile remains were found over a length of 74 meters, it is assumed that a ship bridge spanned the Rhine there. A bridgehead on the north bank at Arach secured the crossing. At the end of the 3rd century a new bridge, probably made entirely of stone, was built a little further upstream under the protection of the late antique fort. It has not yet been proven archaeologically; however, the foundations of the bridgehead suggest that it stood a little further east of today's Rhine bridge.

Vicus

Excavations since the 1970s have provided more precise information about the building structures of the vicus Tasgetium and the everyday life of its population. However, the course of streets and paths is still largely unknown and the center of the settlement has not yet been discovered. Only two buildings have been completely excavated, including the thermal bath, which was discovered in the 19th century. It was built in the 1st century AD along the embankment, stretched around 500 m in length and around 200 m in width from east to west, was inhabited by a mixed Germanic-Celtic-Roman population and soon developed into a regionally important market town. On both sides of the street, the first wooden or half-timbered buildings with living and utility rooms ( strip houses ) were built from the 1st century AD , which were replaced by stone buildings from the 2nd century at the latest. In between was a dense system of water pipes and sewers. The building plots located on marshy terrain had to be drained with an elaborate wooden canal system. The feces from the latrines were also disposed of with these drains. Fresh water was supplied via pipes made of wooden pipes and led into well shafts carefully lined with wood. So that the walls could not sink into the unstable building site, the foundations were placed on pilots and elaborate substructures were built. The investigations of the past years also revealed the presence of a massive wall north of the street, which was interpreted as a bank retaining wall. The main street led directly to the Rhine bridge, on which the public buildings, such as a thermal bath and a latrine made of oak, stood. The multi-phase, approx. 21 × 13 meter large bathing complex made of mortar quarry stones had three rooms with underfloor heating (hypocaust) and painted walls. An inscription reports that it was restored by Caratus, Flavius Adjectus, Aurelius Celsus and Ciltus ( balneum vetustat [e] ). Temples, the forum, the town hall (curia) and port facilities have not yet been discovered. The flammable businesses or those with a strong odor nuisance were concentrated on the western edge of the settlement. Here were among other things pottery with simple dome ovens made of clay and metalworking workshops. There was a burial ground on the road to the south. On the area of the former Vitus Church and its cemetery, a section of the main street of the Vicus running in west-east direction was discovered. It ran along the banks of the Rhine and consisted of a grate with a five-meter-wide gravel layer. Road ditches on both sides ensured rapid drainage of the roadway. The street was accompanied by a porticus, the sidewalk of which was strewn with fine sand. It was probably already in the late 1st century BC. Created. Your route could have been used in pre-Roman times. The road was certainly used until the settlement was abandoned in the 3rd century. The wagon wheels created deep grooves in the gravel pavement so that the gravel pavement had to be renewed at regular intervals. This resulted in a mighty sequence of layers over the course of time, a section of which is on display in the Museum of Archeology in Frauenfeld.

economy

The vicus was a regionally important business location from the 1st to the 3rd century. Trade and commerce benefited from the connection to a well-developed road network and from the Rhine bridge. Since the militarily guarded imperial border ran far north of the Rhine between the later 1st and the later 3rd centuries, there was no need to fear looters for a long time and the Dekumatland also had a rich hinterland. High -quality handicraft goods such as colored glass bowls, terra sigillata dishes, but also food such as wine, olive oil, pomegranates and even fresh oysters were therefore imported from all provinces of the Roman Empire and offered for sale at the Tasgetium markets. Weights of scales, price tags and numerous coins show that trade flourished. The potteries in the south-east and south-west of the settlement were particularly important in terms of handicraft businesses. The names of some ceramic producers have also become known from the pottery stamps: Germanus, Attilius and Raeticus. Discarded pieces and finished products made of leather and wood testify to the presence of a cobbler and a turner. Numerous remains of bones and antlers also provided detailed insights into the craft in Tasgetium. Cones of horns indicate tanneries, bone, antler and typical scrap pieces indicate a leg carver. Slag and iron objects suggest a forge. Fragments of amphorae and wooden wine barrels also document the import of wine to Tasgetium . Numerous graffiti and brand stamps from the wine producers had been preserved on the salvaged white fir boards of the barrel fronts. On them, among other things, the names Gaius Antonius Spendius and Lucius Cassius Iucundus could be read, who possibly had their wineries in Gaul, Italy or in the closer vicinity of Tasgetium.

When the Rhine became the Roman border again after 260 and the danger from barbaric looters increased, the economic conditions in Tasgetium deteriorated. The archaeological finds show, however, that under the protection of the fort in the 4th century a modest prosperity could be maintained, perhaps also through trade with the Alemanni on the other bank.

Burial ground

The Tasgetium burial sites were along the road links to Pfyn and Oberwinterthur, one was discovered in the center of Eschenz. In 1974 a burial ground was discovered around 250 meters southwest of the fort. Of the 47 burials uncovered so far, the older ones face north-south, while the younger, presumably Christian burials, face west-east. Simple burials dominated; in two cases there were walled plate graves; iron nails recovered from it suggest a coffin. There were often various kinds of vessels as gifts. The members of the local upper class were given valuable Lavez and glass vessels with them in their graves, such as the so-called hunting bowl and a jug with an inner jug. Occasionally, items of costume and jewelry such as hairpins, arm rings, mirrors, combs, brooches, pearl necklaces and belt buckles were found. It is unclear whether the soldiers from the fort were also buried in the cemetery. In 1913 five Roman body and three cremation burials were discovered in the area of today's Johanneskirche.

Monument protection and remains

The fort area is a historical site within the meaning of the Swiss Federal Law on Nature Conservation and Heritage Protection of July 1, 1966, and is subject to federal protection. Unauthorized investigations and targeted collection of finds constitute a criminal offense and are punishable by a prison sentence of up to one year or a fine according to Article 24.

Hints

A selection of found objects can be seen in the “Blauer Aff” museum, the Allerheiligen Museum in Schaffhausen and the Museum of Archeology of the Canton of Thurgau in Frauenfeld. The individual sites are connected and described with an archaeological trail. Tasgetium is accessible to tourists through the Neckar-Alb-Aare Roman road and the Lake Constance cycle path.

See also

List of forts in the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes

literature

- Office for archeology of the canton of Thurgau (ed.): Tasgetium I - the Roman Eschenz. 2011, ISBN 978-3-905405-20-0 . (Volume 17 of the series "Archeology in Thurgau".)

- Jakob Christinger: On the older history of Burg-Stein and Eschenz . In: Thurgau contributions to patriotic history 17 , 1877. P. 4–20

- Barbara Fatzer: Early Roman settlement in Tasgetium . In: CH-Forschung 6 , 1998. S. 4 f.

- Bettina Hedinger, Urs Leuzinger: Tabula rasa: Wooden objects from the Roman settlements Vitudurum and Tasgetium . Frauenfeld / Stuttgart / Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-7193-1282-8 .

- Markus Höneisen: Early history of the Stein am Rhein region. Archaeological research on the outflow of the Untersee . In: Schaffhauser Archeology 1 . 1993.

- Verena Jauch: Eschenz - Tasgetium: Roman sewers and latrines . In: Archeology in Thurgau 5 . Published by the Department of Education and Culture of the Canton of Thurgau. 1st edition, Frauenfeld 1997, ISBN 3-905405-05-9 .

- Charles Morel: Castell and Vicus Tascaetium in Raetia . In: Commentationes Mommensi . Berlin 1876. pp. 151–158.

- Bernhard Schenk: The Roman excavations near Stein am Rhein . In: Antiqua 1883. pp. 67-71 u. Pp. 73-76.

- Bernhard Schenk: The Roman excavations near Stein am Rhein . In: Writings of the Association for the History of Lake Constance and its Surroundings 13 , 1884. pp. 110–116

- Elisabeth Ettlinger : The small finds from the late Roman Schaan fort . In: Yearbook of the Historical Association for the Principality of Liechtenstein 59, 1959, ( digitized ).

- Jördis Fuchs: Late antique military horrea on the Rhine and Danube. A study of the Roman military installations in the provinces of Maxima Sequanorum, Raetia I, Raetia II, Noricum Ripense and Valeria., Diploma thesis, Vienna 2011.

- Hildegard Urner-Astholz: The place name Tasgetium and its development to Eschenz , yearbook of the Swiss Society for Prehistory = Annuaire de la Société suisse de préhistoire = Annuario della Società svizzera di preistoria, 1939.

- Friedrich Hertlein , Peter Goessler : The streets and fortifications of the Roman Württemberg . (Friedrich Hertlein, Oscar Paret , Peter Goessler: The Romans in Württemberg . Part 2). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1930.

- Hansjörg Schmid, Hans Eberhardt: Archeology in the area around the Heuneburg. New excavations and finds on the upper Danube between Mengen and Riedlingen. Lectures from the 2nd Ennetach working discussion on March 18, 1999 and booklet accompanying the exhibition in the Heuneburg Museum (May 21 - October 31, 1999) . Society for Prehistory and Early History in Württemberg and Hohenzollern, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-927714-38-0 (Archaeological Information from Baden-Württemberg 40), p. 101.

- ETH Zurich : The gold cup from Eschenz , Zurich 1975, doi : 10.5169 / seals-166350

Web links

- Hansjörg Brem: Tasgetium. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- information sheet

- Reconstruction of the fort, bridge and opposing fort

- Wall remains at the southeast corner of the fort

- Reconstruction of the civil settlement

- Information video, Römerstrasse Neckar-Alb-Aare: The Roman Tasgetium, on YouTube

- Location of the fort on Vici.org

Remarks

- ↑ Hildegard Urner-Astholz 1939, pp. 158–159, Julius Cäsar bellum Gallicum , V, 25

- ↑ Elisabeth Ettlinger 1959, pp. 231–232

- ↑ Friedrich Hertlein, Peter Goessler: 1930, pp. 172–177.

- ↑ Hansjörg Schmid, Hans Eberhardt 1999, p. 101.

- ^ Archeology Canton Thurgau: Walk through the history of Eschenz

- ^ Museum of Archeology Thurgau

- ↑ Jördis Fuchs: 2011, p. 79

- ↑ Jördis Fuchs: 2011, p. 57

- ↑ Jördis Fuchs: 2011, pp. 57 and 78

- ↑ Vernea Jauch 1997, p.

- ↑ Swiss Federal Law on Nature Conservation and Heritage Protection 1966 (PDF; 169 kB).

- ↑ Book description (PDF; 337 kB) ( Memento of the original from December 20, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , from the website of the Office for Archeology of the Canton of Thurgau, accessed on November 29, 2012.