Arbon Castle

| Arbon Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Arbor Felix , b) Felicis Arbore , c) Arbore |

| limes |

Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes (DIRL) Raetia I |

| Dating (occupancy) | late 3rd to 5th centuries AD |

| Type | Cohort fort |

| unit | Cohors Herculea pannoniorum |

| size | 0.65 ha |

| Construction | Stone construction |

| State of preservation | polygonal structure with protruding rectangular and horseshoe towers , preserved foundations of tower 6 visible above ground |

| place | Arbon |

| Geographical location | 750 517 / 264 655 |

| height | 402 m above sea level M. |

| Previous | Fort Konstanz (Constantia) (northwest) |

| Subsequently | Fort Bregenz (Brigantium) (east) |

| Backwards | Schaan Castle (south) |

Castle Arbon was part of the late antique fort chain of the Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes (province Raetia I) on the territory of modern Switzerland , Canton Thurgau , District Arbon , community Arbon .

The fort is now completely built over by the medieval town center. Although mentioned again and again in the main ancient sources, it could only be archaeologically proven in 1957. So far, it is one of the most recent and most important discoveries of late Roman military installations on Swiss territory.

Surname

In ancient times, the fort square had the Latin name Arbor Felix , which means something like "tree that brings luck or blessings". The name of the square could go back to religious roots: Roman priests (flamines) were traditionally shaven. They buried their shaved hair and cut fingernails under an arbor felix . This was, for example, a tree that was struck by lightning or that bloomed outside of the usual season. Arbor Felix is one of the few Roman castles in northeastern Switzerland that is also mentioned in ancient sources. The name designation can be traced for the first time in the Antonini Itinerarium from the 3rd century and perhaps also emerged from the place name «Arbona», which was widespread in the Celtic settlement area. While the Itinerarium Arbon is still only a fortified post station at the intersection of the Vitudurum ( Oberwinterthur ) - Brigantium ( Bregenz ) or Constantia ( Konstanz ) - Curia ( Chur ) routes, the Tabula Peutingeriana from the early 4th century describes it as a fort . In the Notitia Dignitatum Occ. (created around 400) a tribune stationed in " Arbore " is listed, which had a cohort of Pannonians under its command. The chronicler Ammianus Marcellinus reports that Emperor Gratian moved to the east via " Felicis Arbore " in 378 to support his co-ruler Valens against the Goths .

The terms castra and castrum also appear in the biography of a Catholic saint, Gallus , the oldest medieval source mentioned by Arbon.

Location and topography

The small town of Arbon is located on the southern shore of Lake Constance at an altitude of about 400 m above sea level. d. M. The late antique fort was located directly on the lake shore and is now completely overbuilt by the medieval town center. The northern section of the fort area is almost completely covered by the city palace, the southern section by the Martinskirche or Gallus chapel and a cemetery that was used until around 1890. In between are the medieval castle moat and the castle park.

In ancient times the fort stood on a ten kilometer long, slightly elevated headland that protruded far into the lake ( Worm Ice Age moraine ). Creeks flow into the lake to the north and south, making the bank area heavily marshy (hence the field name Seemoosriet in the north). The ridge enabled easy access to the hinterland ( Thurtal ) and to the Limes road that connected Arbon with the nearest fort Pfyn and fort Winterthur . In the east there were good conditions for a port facility. Massive embankments and brisk construction activity have changed the shoreline significantly since ancient times.

development

The period from the Roman settlement to around 300 AD can only be recorded for Arbon through sparse coin and ceramic finds. After these finds - which were made in the 19th and early 20th centuries - there was first a smaller Roman settlement in the southern area of today's Bergliquartier, west of the medieval town center. It probably developed after the expansion of the military road from Vitodurum ( Winterthur ) to Brigantium (Bregenz) at the beginning of the Christian era, when the Lake Constance area was conquered by the Romans under Augustus , and was inhabited until around 280.

The location of the first Roman settlement on the flat ridge above the lake was probably chosen from a strategic and traffic point of view. However, there is currently no archaeological evidence of a Roman trunk road between Bregenz and Pfyn for the area around Arbon . There are also no recent observations or findings in this area; but the remains of lime kilns discovered on Hilternstrasse in 1991 belong undoubtedly to the early or middle imperial period.

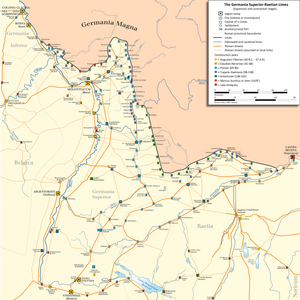

Today's Thurgau was only on the edge of great political world events at this time. However, this should change fundamentally in the late 3rd century, after the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes was abandoned around AD 260. After the Alemanni took over the Dekumatenland from 260 onwards, the Rhine-Bodensee-Line (Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes) became the new imperial border. Numerous new forts were built here, or old ones were repaired, probably on behalf of Emperor Probus (276 to 282); these measures were continued and intensified by Diocletian (284 to 305) and his co-regent (Caesar) Constantius Chlorus (293 to 306). They were able to hold back the collapse of the already crumbling borders of the Roman empire for about a century, because the new border line was better suited for defense purposes than the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes had ever been. Moreover, the province was under Diocletian Raetia divided, the area around Lake Constance fell to the new province of Raetia I .

The civil settlements in the hinterland have now also been fortified, for example, from a building inscription from AD 290, it is known that Viduturum (Winterthur) received a new city wall at that time. The civilian population in rural areas fled to small hill fortresses in the event of danger, which were often hastily built out of blocks from older buildings (Moosberg near Turnau, Lorenzberg near Epfach, Toos-Waldi and Göfis-Heidenburg). Roads into the hinterland were secured by watchtowers or small forts with integrated storage facilities (Füssen and Innsbruck-Wilten). A separate flotilla (numerus barcariorum) was stationed on Lake Constance and had its main bases in Bregenz and Constantia .

The new border forts were considerably smaller than their predecessors, and their floor plan was often adapted to the natural terrain. The walls, on the other hand, were much thicker and were reinforced by cantilevered horseshoe towers on which guns could be positioned. In the Constantinian period (306 to 337) the gaps between the forts, 15–40 km apart, were closed with numerous watchtowers for signal transmission and observation.

Speculations by some researchers regarding the destruction of the Arbon fort at the time of the usurpation of Magnentius (350 to 353) could not be confirmed by the previous excavations. Emperor Valentinian I strengthened the Rhine border again around 370, and in many forts around 400 construction works were carried out under Stilicho . From 406 onwards, the situation deteriorated noticeably. When Army organization and administration of the Western Roman Empire in the late 5th century disintegrated in the region Arbon, remained a majority of the Roman population, probably soon from the now freely flowing Alemanni was assimilated. The Christian-Romanesque community in Arbon Castle was one of the oldest on Lake Constance. Possibly it was the only one that persisted during the turbulent early Middle Ages. The place names Frasnacht and Feilen indicate that there was probably a linguistic boundary between the Alemannic and Romance population groups for a short time . The Alemanni tribes gradually united to form a duchy, which in turn became part of the Franconian Empire in the 7th century .

During this time, Romanesque Christianity only survived in the former Roman forts. When Irish missionaries under Columban reached the area around Arbon around 610 , they found a prosperous Christian-Romanesque congregation in Castrum Arbonense with a presbyter named Willimar, whose spiritual leader was presumably the new bishop - who had resided in Constance since around 585. Columban and his fellow believers initially moved on, but two years later one of them, Gallus , returned to Arbon alone and sick and was nursed back to health by Willimar's confreres. Gallus settled after his recovery as a hermit and sat nearby, in the high valley of the Steinach a hermitage one. The St. Gallen Monastery was later built in its place . He finally died very old in Arbon.

From the 8th century Arbon belonged to the property of the diocese of Constance, founded shortly before 600 . With the introduction of the Franconian county constitution, the Arbon fort fell from the royal estate to the Bishop of Constance. This was now the master of the Arbongau and thus also of his church organization. The fort itself is likely to have lost its substance and structural integrity no later than the construction of the episcopal castle in the 13th century.

Research history

For the first time, Roman finds in the 18th century are reported in a manuscript by Johann Melchior Mayer (... different Geltleyn with old keyser-like coins) , there is no mention of walls. The next coin finds are not mentioned again until the 19th century and Johann Adam Pupikofer noted in 1820 in his history of Thurgau, among others, about Arbon:

“ But the ruins, which can still be found outside the city walls after most of them have been used up by the construction of the city or have been weathered, and the location so advantageous for the connection of the road between Rhaetia and Gaul are weighty evidence that Arbon probably existed in this area from the beginning of Roman rule "

Between 1864 and 1902, Roman coins, ceramics and remains of walls were repeatedly found on the southern slope and on the Bergli plateau. In 1896, Jakob Heierli summarized the state of knowledge at the time in an archaeological map of the canton of Thurgau.

Systematic research, however, began late. After the Arbon fort had long been suspected to be in the Bergliquartier, in 1957 semicircular foundations of an ancient building (tower 1) were actually discovered on the west side of the castle. Archaeological excavations have been carried out at regular intervals since 1957 in order to be able to shed more light on Arbon's Roman past. In the course of this, the existence of a typical late Roman fort could soon be proven.

The soil surveys carried out by Elmar Vonbank between 1958 and 1962 were primarily aimed at determining the actual size of the facility and the exact course of the fort wall (area of the city palace and St. Martin's Church). However, Vonbanks only has handwritten records of these campaigns. For the subsequent analysis, the extensive photo documentation from 1961 and 1962 had to be used for the most part.

During the excavations in 1973, 1986 and 1990, other important parts of the fort in the area of the city palace and the parish church were discovered. In 1973 and 1986, the Thurgau Office for Archeology also examined smaller areas inside the fort. In 1990 the remains of the western fort ditch were finally located 50 m from the western wall front and three lime kilns were uncovered in Hilternstrasse 1500 m south of the fort. The excavations in the fort were always subject to narrow spatial and financial limits, so that only a fraction of the area, around 800 m², could be examined to date.

Fort

Despite a few older Roman finds on the Bergli, the excavators assume that the fort was built on mostly undeveloped land. According to the findings, it covered an area of around 10,000 m² and stretched from the eastern tip of the mountain hill to just about the shore of Lake Constance. Its north-south extension was 110 m, the east-west axis about 80 m. The north-west corner, sections of the north and west front and the western part of the south wall were located, plus a few smaller sections in the castle park and south of the church. Gate systems are accepted in NE and SE (see tower 4 and 5). The port facility of the fort is believed to be east of the mountain hill.

There are indications for the wall ring, towers and moat that speak for the construction of the fort in one go, since the construction of the fort wall and the towers do not differ significantly from one another. Horizontal scaffolding holes typical for late antique buildings could not be discovered, only to the west of the castle tower were small holes in the mortar layer of a foundation plate, which were probably impressions of scaffolding poles. Individual construction phases, traces of alterations or repairs were not recognized.

The masonry was raised using the cast wall technique typical of late Roman antiquity. First, the two facing surfaces were built up with selected stones placed in regular layers and then the space in between was poured with an extremely resistant lime mortar mixed with unprocessed creek rubble (partly with chipped heads in the forehead area). Spolia (building stones or tombstones in secondary use) were also used for the cladding at the NE gate.

The top of the foundation was about five meters above that in the south in the north. Due to their width, they are to be viewed as whole slabs that were not completely built over (protruding external and internal foundation). Its bottom layer was designed as a drainage. The foundations consisted of large stone blocks, while the rising masonry consisted of much smaller ones with a diameter of 10–15 cm.

Fort wall

To date, only 80 m of the fort wall has been examined more closely. Numerous finds of bricks and mortar testify to their destruction and decay. The fort wall, presumably up to 350 m long and 1.8–2.6 m thick, essentially followed the natural course of the hill, which gave the complex its irregular shape. It is also noteworthy that the remains of the wall on the land side were 2.60 m thick, whereas those on the sea side were only 1.80 m thick. Very little is known about the course of the wall in the east and northeast; it probably followed the former lakeshore line between towers 5 and 6. From tower 6 it probably ran along the northern edge of today's harbor or main street. A gate system is suspected in this area. The position of the wall on the city side is also completely unknown. The south wall of the Gallus Chapel exactly follows the fort wall, which means that at the time the chapel was built in 12/13. Century must have been visible.

Gates and towers

Six wall towers were completely or at least partially excavated. With four towers only the foundations were left. Only towers 6 and 4 were a little better preserved. Four semicircular towers (horseshoe towers) and two square intermediate towers (No. 4 and 5) in the west, north and south reinforced the excavated sections of the curtain wall at intervals of around 22 m. At 22 m, the center distance of the towers in Arbon is significantly less than that of Fort Pfyn (36 m). The distances between the towers of the Eschenz / Stein am Rhein fort, at 20 m on the southern and 30 m on the western and eastern front, indicate that the construction crews have plenty of scope for planning and execution.

Horseshoe Tower 1

The tower was located immediately north of a slight bend in the fort wall; it was completely destroyed when a toilet facility was built. The photos taken in 1957 show that the foundation consisted of the unmortured rubble. In the area of the front of the tower it was arranged in an arc and protruded about 3.10 m in front of the wall. The width of the tower was 7.10 m, its back protruded 0.85 m into the interior of the fort. Two layers of stone of the rising masonry were still visible on the north wall. The floor level inside the tower was not reached during the excavation.

Horseshoe Tower 2

This tower, on the other hand, stood exactly at a kink in the fort wall. From him only his enemy-sided outer curve (basket arch) could be examined; the back of the tower was completely built over. The foundations were preserved up to a height of 2 m. Its diameter was 6.40 m, the outer radius 10.40 m. At the transition to the north outgoing fort wall and some were spoils been installed.

Horseshoe Tower 3

This tower had been severely disrupted by the construction of the Landenberg tract of the city palace. He secured the northwest corner of the fort. Only parts of the outer curve could be excavated from it. The outer radius was 3 m, the total circumference was 10.40 m. It concentrically encloses the wall angle of the camp wall. Its foundation slab protruded extremely strongly towards the north - probably for static reasons.

Rectangular towers 4 and 5

Tower 4 stood 45 m east of tower 3. But there was probably another intermediate tower between 3 and 4. Their construction differs somewhat from the usual layout of the other examples. Numerous spoils were processed for them, which mainly facilitated the shaping and the corner connections. These blocks used a second time had clamping, lifting and mortising holes, and traces of reworking could also be found. They probably originated from a public building or monument (high processing quality, dovetail-shaped chisels for lead clips), as could be proven, for example, with the Spolia in Pfyn. Other spoils could only be discovered at the connection between tower 2 and the fort wall. The facings of 4 and 5 consisted of sandstone blocks and tuff stones.

The outer foundation of tower 4 consists of 90 × 65 × 45 cm large sandstones. In Tower 5, even larger blocks of this type were walled up in its foundation - otherwise consisting of mortar rubble - this material was otherwise hardly found in Arbon. During the follow-up examinations carried out in 1991, a long rectangular floor plan with the dimensions of 8 × 4.60 m was found at tower 4, its rear protruding around 2.40 m into the interior of the fort. The wall widths were 1.20–1.40 m (on the enemy side). The inside of the tower was divided into two rooms. It probably served as the western flank tower of the NE gate system.

Tower 5 could also have been part of a gate system. Today it lies almost entirely under the medieval Gallus Chapel, near the ancient shores of Lake Constance. It evidently played a special role in the fort's defense system, as it was the connection between the land and harbor walls (width 2.40 m), which were considered to be particularly exposed, and the probably less endangered bank walls (width 1.80 m). The external dimensions of the tower were 9 × 10.50 m, those of the internal area 4.60 × 5.60 m. Its wall thickness also varied, an impressive 2.70 m on the enemy side and only 2.20 m on the fort side. The tower protruded about 4 m on the enemy side of the fort wall. Its construction is similar to that of tower 4, but here the walls, which consist only of blocks, were missing. The foundation slab probably also consisted of mortared creek rubble.

Horseshoe Tower 6

This tower was the only architectural component of the fort that was restored and conserved and is visible above ground. He secured the SW corner of the fort. The arched cage, which was slightly forward, had a radius of 4.40 m and protruded about 5.60 m in front of the fort wall. The length of the central tower axis was 5.10 m. Strangely enough, the wall thickness of the basket arch was only 1.60 m in contrast to the rear wall on the fort side, which was 2.40 m thick. The tower also had an access gate at its rear, which was approximately 1.10 m wide. Their threshold was around 1 m above the floor of the interior. This may indicate a wooden floor construction on the first floor. Such soils have also been found in other watchtowers on the Rhine border. In some places small remains of a white, coarse-grained interior plaster could be observed. Elmar Vonbeck interpreted the finds of individual hollow brick fragments ( tubulus ) as part of a heating system in the tower, but in the opinion of the excavators they almost certainly come from the camp thermal baths under the parish church.

Fort moat

In 1990, on the occasion of the construction of an underground car park on the Fischmarktplatz, the long-sought-after moat was discovered. The 4.10 m wide bottom of the trench rose slightly towards the west and then merged directly into the steep, enemy-side trench embankment. The trench was probably originally a little wider at the top and thus also much deeper. A securing of the trench walls by fascines, as observed for example at the Altrip fort on the Rhine , could not be determined. The trapezoidal, 8.8 m wide and 3 m deep moat to the west of the fort reached down into the groundwater area, which fortunately supports the preservation of organic finds from the 4th century such as an oak stave barrel , a hollowed-out tree trunk and the fragments of a (probably) left closed Roman leather shoe ( calceus ) with it. In the hollow of the tree trunk there were some iron parts and a bronze arm ring, in the oak barrel coins, fragments of a goat or sheep skull as well as glass and ceramic shards. It is difficult to judge today what function these two "tubes" had; they may have served as water collecting tanks or tanning vats.

The cause of the unusually wide berm (around 50 m) between the fort wall and the moat could not be clarified with certainty . It is conceivable that the above-mentioned ditch belonged to an older fort, or that the late antique fort was surrounded by a double ditch. The latter was supported by observations made in 1991 during the demolition of a house in Promenadenstrasse, where a ditch came to light that ran parallel to the ditch on the Fischmarktplatz. But it could also have belonged to the medieval castle, since there were no datable finds from its backfilling.

Interior development

The interior of the fort has almost completely fallen victim to medieval building activity. Smaller stray finds of Terra Sigillata from the 2nd to 3rd century AD suggest that there were even older Roman settlement activities in this area. Of the late antique interior structures, only a few remains of buildings in the area of today's castle courtyard and a thermal bath under the parish church of St. Martin have been known since 1992 . The exact dating of the foundations (presumably of two buildings) in the castle courtyard was not possible. The remains of the camp thermal bath gave a vague indication of the possible arrangement of the buildings inside the fort; their foundations were later used again in the construction of the church.

Building a

In 1973, parts of the wall running from north to south were exposed in the eastern courtyard. They consisted of an approximately 14 m long west-east wall section with an extension to the NE and a 2.50 m long wall corner in the southern part of the courtyard. The width of the foundation was 1.10 m. The wall itself was 1.65 m wide and still had 30 cm high rising masonry. The facings were built from rubble stones laid in layers. Some of the blocks had not had their heads chopped off. The wall core was filled with lime mortar and small rubble stones. Remnants of plaster could still be observed in the inner part of the bend. A floor screed was attached to the wall. In addition, a 1.28 m door threshold was discovered.

These remains of the wall were probably a room partition within a much larger building. However, there was no direct connection to the corner of the wall in the eastern part of the courtyard. If they were put together, Building A would have an estimated total length of 29 m. The findings indicate - viewed in their entirety - a large hall-like building. Such buildings have also been found in Kaiseraugst, Yverdon, Kellmünz and Eschenz.

Fort bath

In 1986, in the course of the restoration of the interior of the church of St. Martin, an approx. 26 m² grid square was examined for finds from the Roman era. In the western part of the nave, the remains of two Roman buildings from different time periods were found. The function of the older building could not be determined.

The younger complex was, however, undoubtedly a bathing building which probably dates from the Constantinian period. In summary, the NW parts of his caldarium could be identified with a rectangular tub annex (1.30 × 2 m), praefurnium and hypocaust system. The brick-vaulted heating channel (width 90 cm) of the prefecture broke through the protruding west wall of the tub extension. Along the watertight plastered tub there were 8 hollow bricks (tubules) that diverted the hot air upwards through the wall. The width of the caldarium west wall and the tub annex was 0.74 m, they were plastered on their outside and inside. The bathing room (with annex and prefurnium) had a total circumference of 7.80 m. The 14 hypocaust pillars that were preserved consisted of 5 cm high bricks and were on average 90 cm high. A square wall plinth placed between the hypocaust pillars could have been the substructure for another water basin.

Other interior constructions

Apart from the buildings in the castle courtyard and under the parish church, remnants of the interior buildings could also be observed in other areas. Finds made by Elmar Vonbeck of reddish screed floors on the foundation plate of the wall indicate buildings along the fort wall. To the north of the fort wall, a mound of rubble made up of small fragments of roof tiles, all without stamps or wiping marks, was discovered. This find indicates tiled roofs in the fort.

garrison

Little is known about the units stationed in Arbon. In the Notitia Dignitatum is in the troops list of Dux Raetiae for Arbon just a "Tribunus cohortis Herculeae Pannoniorum, Arbore" (a tribune of the cohort of Pannonians the Hercules of under the command of Arbon) entered Dux of the provinces Raetia I and II was . The nickname "Herculae" suggests that this unit was set up among the Tetrarchs . It was probably originally part of the army of Diocletian's co-regent Maximianus , who had placed his rule under the protection of the god Herculius (Latin for Hercules ). Secular power continued until long after the end of Roman and Gothic rule by a tribunus Arbonensis , who was primarily responsible for a dux from the province of Raetia . A man named Talto is known by name for this period of time. His official title suggests the continued existence of an administrative and military organization in the Ostrogothic empire of Theodoric , largely based on the late Roman model . These officers can be traced back to Arbon as far back as the Franconian Empire in the 8th century. B. a tribune called Waltram the garrison of the fort.

Burial ground

The ancient burial ground was about 500 m west of the fort and is today largely destroyed by the modern overbuilding. References to graves from the 4th century are not recorded for Arbon. The early medieval residents of the fort were probably partly buried in a burial ground on the mountain hill, which was documented until the 7th century. Relevant finds have repeatedly been made in this area (skeletons, swords). So far 49 burials have become known, albeit with very few fundamentals. A schematic plan by A. Oberholzer shows the Roman building floor plans on Rebenstrasse as well as the east-west facing burial ground on the southern slope of the Bergli. The finds from the burial ground were never processed in a comprehensive way, older reports were fragmentary or only dealt with individual finds.

Dating and strategic importance

The sparse finds from the 4th century do not allow any definite statements about the time this fortress was built, but it is possible or very likely that it was built in the late 3rd or early 4th century. The majority of the coins found in the fort date from the time after 300 AD. The series of coins begins with Diocletian, 285 AD and ends with Arcadius and Honorius , 408 AD, the majority of the datable small finds also come from the time between 300 and 400 n. Chr. use horizons in the northwest and south of the storage area and the local accumulation of finds from the late antiquity and the stratigraphic observations led the excavators also concluded that the attachment at the latest in the reign of Constantine I built must have been. An origin under Valentinian I (367–368 AD) can definitely be ruled out according to the available excavation results.

The Arbon fort was probably built together with Tasgetium (Eschenz / Stein am Rhein), Ad Fines (Pfyn) and Constantia (Constance) to secure the Limes (border wall) that was moved back from the upper Danube to the Rhine and Lake Constance . It belonged to the first line of fortifications of the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes , as evidenced by an inscription made of Stein am Rhein. The fort possibly also served as a starting point for the Roman Lake Constance flotilla (numerus Barcariorum) , which had its headquarters in Brigantium / Bregenz. The most important task of the fort crew was probably the monitoring of the road connection to Pfyn and Bregenz and the observation of the lake shore.

After 403 AD, the Roman rule over the Thurgau gradually dissolved, but the fort was still used by the local population ( oppidum ). The early medieval burial ground on the Bergli, the survival of the term castrum in medieval sources and the clear description of the place in the Gallus Vita also demonstrate the continuity of settlement for Arbon.

Notes and whereabouts

The Historical Museum Arbon shows a permanent exhibition based on the latest findings in the medieval rooms of the castle complex and thus offers a journey through time through Arbon's 5500-year history. The Neolithic, Bronze, Roman, Middle Ages, canvas trade in the 18th century and industrialization in the 19th and 20th centuries are presented in a lively and easily understandable way with some unique exhibits, pictures, documents and meaningful short texts. Unless exhibited in the Arbon Museum, the small Roman finds are kept in cantonal depots.

Monument protection

The fort area is a historical site within the meaning of the Swiss Federal Law on Nature Conservation and Heritage Protection of July 1, 1966, and is subject to federal protection. Unauthorized investigations and targeted collection of finds constitute a criminal act and are punishable by imprisonment of up to one year or a fine according to Art. 24.

See also

List of forts in the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes

literature

- Hansjörg Brem, Jost Bürgi, Kathrin Roth-Rubi: Arbon - Arbor Felix. The late Roman fort. (= Archeology in Thurgau 1, publication by the Office for Archeology of the Canton of Thurgau ), with contributions by Peter Frei, B. Kaufmann, Max Martin and Barbara Scholkmann. Department of Education and Culture of the Canton of Thurgau, Frauenfeld 1992, ISBN 3-905405-00-8 .

- Norbert Hasler, Jörg Heiligmann, Markus Höneisen, Urs Leutzinger, Helmut Swozilek: Under the protection of mighty walls. Late Roman forts in the Lake Constance area. Published by the Archaeological State Museum Baden-Württemberg, Frauenfeld 2005, ISBN 3-9522941-1-X .

- Hansjörg Brem: From Valentinian I. to St. Otmar. The early Middle Ages in Thurgau. In: Archeology of Switzerland 20, 1997, 86–90 PDF .

- Markus Höneisen, Kurt Bänteli, Jost Bürgi (Eds.): Early history of the Stein am Rhein region, archaeological research on the outflow of the Untersee , Swiss Society for Prehistory and Early History, Schaffhauser Archäologie 1, 1993, ISBN 3-908006-18-X .

- Lothar Bakker: Bulwark against the barbarians. Late Roman border defense on the Rhine and Danube , in: Die Alamannen , exhibition catalog, ed. from the Archaeological State Museum Baden-Württemberg, Theiss, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-8062-1302-X .

Web links

- Alfred Hirt: Limes. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- The effects of the Great Migration in Switzerland (Swiss History website)

- Location of the fort on Vici.org

Remarks

- ↑ Ammianus, res gestae 31, 10, 20 ... per castra quibus Felicis Arboris nomen est.

- ↑ a b Hansjörg Brem: Arbon - 2 Roman times. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . October 20, 2010 , accessed July 3, 2019 .

- ↑ Lothar Bakker: Die Alamannen , 1998, p. 115.

- ^ So Overbeck 1, p. 213 with notes on p. 319; "After an interruption, however, the small series of coins only continued again under Valentinian."

- ↑ Brem, 1992.

- ↑ Jakob Heierli: The archaeological map of the canton of Thurgau with explanations and find register. In: Thurgauische contributions 36, 1896, pp. 123–125.

- ↑ Vonbeck speaks here of the so-called " Rorschacher sandstone ". In his opinion, these blocks all come from a single building or monument, which does not necessarily have to be in Arbon.

- ↑ See Walter Drack: Wachturm Tössegg-Schlössliacker , pp. 36–38.

- ↑ Brem / Bürgi / Roth-Rubi 1992, p. 38.

- ↑ Brem / Bürgi / Roth-Rubi, 1992, p. 50.

- ↑ Notitia Dignitatum occ. XXXV

- ↑ Sankt Otmar. The sources for his life , in Latin and German, ed. by Johannes Duft, 1959; Helvetia Sacra III 1, 2, 1986, p. 1266 ff .; The culture of St. Gallen Abbey , ed. by W. Vogler, 1990; W. Berschin: Biography a. Epoch style in Latin MA Vol. 3, 1991; Arno Borst: Monks at Lake Constance 610–1525. 4th edition 1997; [1] .

- ↑ Elmar Vonbeck, 20, RCH, 322

- ↑ Brem / Bürgi / Roth-Rubi, 1992, p. 176.

- ↑ cf. Markus Höneisen: The late Roman fort Stein am Rhein , 1993.

- ↑ Viereck, 1996, p. 258.

- ↑ Vita Sancti Galli, chap. 30, after fragrance, Gallus 49: “The rumor of illness (of Gallus) reached the ears of many and also reached the aforementioned Bishop Johannes of Constance. This could not be satisfied now than until he had visited his master. And because he had received heavenly and earthly treasures from his help and teaching, he took worthy gifts with him into the ship and hurried to the Arbon castle. When he entered the port there, you could already hear the babble of voices mourning the man of God. "

- ↑ Swiss Federal Law on Nature Conservation and Heritage Protection 1966 (PDF; 169 kB).