Constantia Castle

| Fort Constance | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Constantia / Confluentibus |

| limes |

Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes , route 3 |

| section | Raetia I . |

| Dating (occupancy) | Diocletian, before / around 300 AD to before / around 402 AD |

| Type | Fleet fort (Fort III) |

| unit | Numeri Barcariorum |

| size | 80 meters × 150 meters |

| Construction | Steinkastell (Fort III) |

| State of preservation | presumably diamond-shaped fortification with octagonal towers, still visible above ground |

| place | Constancy |

| Geographical location | 47 ° 39 '48.1 " N , 9 ° 10' 33.5" E |

| Previous | Fort Arbon ( Arbor Felix ) (southeast) |

| Subsequently | Fort Stein am Rhein ( Tasgetium ) (northwest) |

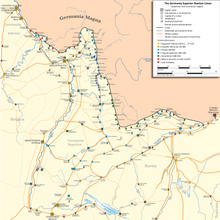

Constantia is the collective term for a late Roman border fort of the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes , as well as for a civil settlement from the high imperial and late antique periods . You are in the area of Konstanz in the German district of Konstanz .

The oldest traces of settlement go back to the younger Stone Age. From the 1st century BC The existence of a Celtic settlement is known from the 1st to 3rd century AD, the Romans built several forts on today's cathedral hill to defend the border. Constance was at the intersection of several roads to Northern Italy, Gaul and the east of the Roman Empire and advanced to become an important trading center. The Roman Lake Constance fleet also had a base there. The excavations in the early 2000s finally led to the discovery of a late Roman frontier fort of the 4th century AD - which has been suspected here for a long time. It proved that Constance was not only introduced as a bishopric since the Middle Ages, but obviously also in late antiquity significant place was. Comparable forts stood in neighboring Stein am Rhein and Arbon (Switzerland). From the Roman military camp, today's city developed in the early Middle Ages and has retained its ancient name to this day.

location

The late Roman fort of Constance was in a convenient location on the south bank of Lake Constance, where the Obersee flows into the Seerhein. It is towered over by the moraine embankment , the cathedral hill, which rises around five to seven meters above the water level . The highest point in today's Constance city area at the Konstanzer funnel , where the Rhenus ( Rhine ) leaves the Lacus Constantinus ( Lake Constance ), south of the Lacus Rheni ( Seerheins ). The foothills of the Alps and the area around the mouth of the Rhine could be seen from here. Unlike today, this hill formed a narrow headland in prehistoric times, only accessible from the south , which was surrounded by bodies of water and swamps to the west . Only in the course of high medieval and modern settlement activity did the buildable area continue to grow through embankments. Constantia was part of the late antique Limes of the province of Raetia . In the course of the Diocletian imperial reforms in 297 AD it was added to the newly formed province of Raetia .

Surname

Traces of Roman settlement can be found in Konstanz since the 1st century. In the Geographike Hyphegesis of Claudius Ptolemaeus (around 160 AD) a settlement called Drusomagus (= large oak forest ) is found. mentioned (Ptolem. Geogr. 2,12,3), which a research group claims to have identified in 2010 as today's Constance. The location of Drusomagus is, however, still controversial; It remains to be seen whether the new approach will prevail. It is not known how the Roman settlement on Münsterhügel was called.

The first written mention of the place name Constantia (= resistance ) comes from around 525 and can be found in the travel guide of the Ostrogoth Anarid , written in Latin . It also appears on a Roman road map ( Tabula Peutingeriana ) of the 4th / 5th centuries. Century. In the Rhaetian troop list of the Notitia Dignitatum , one of the most important sources for the early 5th century, one of the two bases of the Roman Lake Constance flotilla is referred to as the Confluentibus . Due to the context, it is assumed that this does not mean Koblenz , but Constance. May have been Confluentes the former name of the settlement before it was renamed. The late antique fortress seems to have had a certain importance, as it was obviously named after one of the emperors of the Constantinian dynasty. This would include Constantius I (Chlorus), who had won several victories over the Alamanni around the year 300 and stabilized the Limes of the Roman Empire on the Rhine and Danube. According to other researchers, Konstanz bears the name of his grandson, Emperor Constantius II , who also took action against the Alamanni on the Rhine and in the Raetia in 354 and 355 and therefore probably stayed in Konstanz for some time. Since then, the place could bear his name on this occasion. The geographer of Ravenna mentions in his Cosmographia , created around 700, a Civitas Constantia .

Research history

The first soil tests were carried out by the pharmacist Ludwig Leiner and the history student Konrad Beyerle between 1872 and 1898. At that time the surrounding walls of the fort were uncovered on the Münsterplatz and later filled in again. Since 1882, when Ludwig Leiner published a summary of the Roman archaeological finds based on his observations, archaeological research into Roman and early medieval Constantia has not been a good star. Two scientific excavations were carried out in the area around the minster, on which von Leiner had proven Roman settlement.

Paul Revellio , the excavator of the Roman fort Hüfingen , temporarily took over the management of an investigation started by Alfons Beck on the southern Munster hill on behalf of the Baden Monument Authority in Karlsruhe in 1931. Gerhard Bersu , Director of the Roman-Germanic Commission in Frankfurt, dug two excavation cuts on the northern Münsterplatz in 1957. Due to the number and character of the late Roman strata on the southern cloister wall, he suspected that there must have been a late Roman fort in the area of the cathedral hill. Between 1930 and 1960, the teacher Alfons Beck took on the archaeological remains of the city. In the 1960s, during municipal excavation work on Münsterplatz, traces of the Roman fort were found again. However, instead of attempting an archaeological excavation, the water pipes were laid around the site. From the 1970s, Hans Stather worked as a volunteer at the Baden-Württemberg State Monuments Office. 1974–1975, Wolfgang Erdmann and Alfons Zettler supervised archaeological construction work on the southern cathedral hill on behalf of the Baden-Württemberg State Monuments Office in connection with the renovation of the crypt under the Constance Minster. Hans Stather doubted the existence of another fort and assumed an alternative possibility of a walled vicus, a small fortress or a burgus to secure a harbor.

From Constance until 1983, the archaeological experts hardly noticed. This year, as part of a large-scale urban redevelopment program, archaeological research into the history of the city of Konstanz became a priority program of the State Monuments Office. Judith Oexle was in charge of the scientific management . After her departure in 1993, the scientific management of the excavations was transferred to Marianne Dumitrache, and from 1999 to Ralph Röber . These investigations also revealed some new insights into the Celtic and Roman eras of the city.

The remains of the late Roman fortress from the 4th century were from 2003 to 2004 on Cathedral Square excavated . This year the city administration's plans to completely redesign the northern Münsterplatz took shape. The soil encroachment on an area of around 6000 m² in a highly interesting archaeological zone made a large-scale excavation possible, which was scientifically accompanied by the Baden-Württemberg State Monuments Office. The excavations were also carried out with the aid of the latest IT technology and were largely completed by the end of December 2004. Among other things, it produced important results on the Roman history of the city of Constance. After extensive excavations, the wall remains of the late antique tower foundation, trenches and a well were archaeologically examined and appropriately conserved. A total of around 400,000 small finds were recovered, mostly ceramic fragments. The discovery and confirmation of the late Roman fort and the preservation of the structural findings of its enclosures and interior buildings, which were uncovered in small parts, were spectacular. The knowledge about the early Roman military installation and the burial ground on the cathedral hill, which was already known before the excavation, were also instructive. From 2005 to 2007 the first results of the excavations were presented as part of a traveling exhibition “In the protection of mighty walls. Late Roman forts in the Lake Constance area ”presented to a wider public.

Some of the small finds pointing to the late Roman period, the little wheel sigillata, have already been processed by Wolfgang Hübener. It comes from Lavoye and was made in the period from around 330–360 AD. The late type of Terra sigillata indicates Roman military presence on the Konstanz Minster Hill during this period.

development

1st BC to 2nd century AD

Around 58 BC The Romans also recognized the favorable location of the bridgehead-like headland on the southern shore of Lake Constance. Your army probably laid a branch off the major military road from Ad Fines ( Pfyn ) to Arbor Felix or Arbona ( Arbon ) towards Constance and across the Rhine. They protected this transition with a small fort that they built over the destroyed Celtic settlement. It may have served as a naval base on Lake Constance. From 15 BC onwards Its own Roman flotilla on Lake Constance. In any case, it could not have been purely strategic reasons that led to the establishment of this base. Good climatic conditions and very fertile soil may also have played a role here. A small settlement ( vicus ) soon established itself on the cathedral hill , its foundation probably around 20 AD, during the reign of Tiberius . The findings of the excavations on the northern Münsterplatz (including the edge fragment of a terra sigillata cup from the Johanneskirche dating from this time) suggest that the Münsterhügel played a military role since the early phase of the Roman occupation of the Alpine foothills . The Roman troops may have been withdrawn under Emperor Claudius .

3rd to 4th century

In the course of the 3rd century there were serious changes in the Roman Empire that also affected the military. Because of the increased pressure that Rome was exposed to in the north and east (cf. Sassanids ), the border defense was reformed. Many of the older limites were abandoned and people withdrew to more easily defended borders, preferably rivers. Due to the Alemanni invasions in AD 213, 233 and especially 259, the Roman army in Raetia was pushed further and further south. As a result, the Romans moved the Upper German-Raetian Limes back to the banks of the Danube, Iller and Rhine from 260 AD. The newly created Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes , it was hoped, should better protect the new northern border. In the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, several defensive structures were built one after the other on the cathedral hill. The last of them, the late antique border fortress Constantia , was part of the fortifications of the new Limes. It served to secure borders, as well as to protect the Rhine Valley and Lake Constance area against plundering Alemanni , in whose area some of the late hilltop settlements were located. Constantia primarily served the defense and control of the Rhine crossing. The dead of the fort were probably buried in a grave field along Wessenbergstrasse and Hussenstrasse. An onion button fibula that was recovered during the excavation on Münsterplatz and was in use between 290 and 320 AD fits the presumed founding date of the fort . Since the Tasgetium fort, located not far from Konstanz near today's Stein am Rhein , can be dated to the period between 293 and 305 through an inscription, there is much to suggest that the Constantia camp was also built around this time. Apparently a larger civilian settlement expanded again under his protection. Presumably a Roman emperor, Gratian , was staying in Constantia again in 378 when he crossed the road on the south bank of Lake Constance to the east to assist the regent of the east, Valens , in the fight against the Greutungen . According to evidence from the coin finds, it served the Roman military as a border fortress and naval base until at least the end of the 4th century AD.

5th to 6th century

The withdrawal of most of the Roman border troops, which began around 402 AD on the orders of the Western Roman regent Stilicho , did not necessarily mean the complete destruction of the fortress. All forts in the Lake Constance area remained occupied by the regular army until the beginning of the 5th century. Then the Roman rule in this region gradually dissolved. The former military camps and their well-developed infrastructure continued to be used. They continued to offer the civilian population a certain level of protection and security in troubled times. The last known ancient coins in Constance were struck around 408 AD (Emperor Arcadius ). Only individual finds and graves testify to further settlement beyond the end of Roman rule. The first Christian churches were soon built within the fort walls. B. in Arbon (still in Roman times), Stein am Rhein, Pfyn and Oberwinterthur. So these military installations can be seen as the nucleus of the medieval Lake Constance culture. After the official dissolution of the Western Roman Empire in AD 476, the province of Raetia and with it Constance came under the rule of the new ruler in Italy, Odoacer . After his death in 493 it fell to the Ostrogoths and was ruled from Ravenna until 536 . In 537 the Ostrogothic King Witiges had to cede the province to the Frankish King Theudebert I , as compensation for his support in the war against the Eastern Roman Empire ( Gothic War (535–554) ). This also made the region around Constance part of the constantly expanding Merovingian empire .

Post Roman time

The core of the Civitas Constantia mentioned by the geographer of Ravenna was probably the late Roman fort. Its walls also protected the first episcopal church built there. A trading post was a little north of it, as various archaeological finds have shown. Probably around 590, according to an inscription, the bishop Maximus moved his official residence from Vindonissa ( Windisch ), which had become too unsafe due to the migration of peoples, to Constance, which is a little easier to defend. But another incumbent, Cromatius , was first referred to as Bishop of Windisch and a little later as Bishop of Constance. At that time, bishop residences were preferred in populous cities or in existing, larger and more important settlements. The cathedral hill and the road running towards the fort from the south provided the framework for the early medieval settlement. It was around this time that the predecessor of today's cathedral was built within, partly on the foundations of the late antique fortress.

Some guesses as to how long the fortification system lasted can be derived from the latest excavations. An extensive burial ground was observed during the excavation over the late antique findings. It should have been created shortly after the diocese was founded. It is first mentioned in written sources in 1230. Members of the lower clergy were buried here as well as the servants of the bishop and the cathedral chapter and their relatives. Two fragments of the rising fort wall, which fell when it was demolished and were no longer removed, were not found on the ground level of late antiquity, but on the early medieval cemetery horizon. Apparently the ruins of the fort were only removed at this point when the cemetery already existed. With the leveling of the cemetery, the site was prepared for the enlargement of the minster - a measure that u. a. also led to the demolition of further parts of the ancient fortifications. As is so often the case with ancient fortifications, it must have served as a quarry for the church. All that remains of this church is its crypt , which could be dated to the late 8th or 1st half of the 9th century. However, it cannot be concluded from this that all the walls of the fort were removed at this time. A medieval defensive wall, which could not be dated in more detail, was found on the parcel on Richtgasse 12 in the northern apron of the late antique fortress. Their establishment could with Bishop Solomon III. (890–916 AD). The construction of this fortification would only have made sense if the wall on the northern front of the former Roman fort no longer existed or was demolished during this time.

Some of the walls of the fort could have been used until the 9th century and were then almost completely removed in the course of the expansion of the medieval town. At the latest during the time in office of Konrad von Konstanz , between 934 and 975 AD, there should no longer have been any ancient building remains in Konstanz. This bishop commissioned a chapel next to the cathedral, which was dedicated to Saint Mauritius. Konrad had an ancient inscription walled into a side niche, which he had brought from nearby Winterthur. Originally the building inscription of the Fort Vitudurum , which was once there , it was intended to indicate the venerable age of the city named after him through the writing Constantius .

Castles

It is assumed that the nucleus of the settlement on the Münsterhügel was a multi-phase wood-earth fort that had at least two ditches on its south, west and north sides, which were built at different times. The more recent of these systems is assumed to date back to the 2nd half of the 3rd century. For castles I and II there are no indications of the construction of the defensive wall or even of the interior structures. The early forts are only recognizable by discoloration in the earth. At least stone buildings can be excluded there, so that they could only have been occupied by regular soldiers for a short time. Similar findings in the late Roman fort of Vemania (Isny) suggest that the first of these fortifications was built under Emperor Probus (276–282 AD). He is honored on an honorary inscription from Augsburg as a “renovator of the provinces and public buildings”. Contrary to current opinion, which is still widespread, attempts must have been made to secure the new border on the Rhine and Lake Constance even before the rule of Diocletian (284–305 AD). Late antiquity left a mighty wall and an octagonal fortress tower in Constance. At the excavation site in the underground museum - by the wall and tower - the results of the excavations are explained.

Castle I.

The remains of the first, rectangular Roman camp for around 300 soldiers were uncovered in the north of Münsterplatz. From there the steep drop to the Rhine could be viewed. From a stratigraphic point of view, these findings belonged to the first Roman settlement period and disrupted the debris layer of the late Latène period settlement. It was a small section of the north gate. The moat surrounding the fort could only be exposed in the area of the trench head. Here it was around 1.5 meters wide and 0.7 meters deep. It ended in an almost trapezoidal shape with an earth dam at least 7 meters long, which allowed access to the camp. The two flank towers were built in the timber construction typical of early imperial systems. It was possible to observe four round post pits (diameter 0.9 meters) arranged in a row, in the fillings of which the imprints of the rectangularly cut posts measuring 30 × 30 cm were clearly visible. They once supported the western gate tower, which jumped back about 6 meters into the interior of the camp at its rear. The gate towers, whose ground plans could only be captured through their post pits, date from the Augustan period (15 BC - 14 AD).

Castle II

Further excavations on the Münsterhügel yielded more precise information about the two subsequent fortifications from the 3rd century AD, which had been known for a long time. The course of the north wall of camp II could first be recognized. It had a skewed, northwest-oriented ground plan and covered an area of around 1.2 hectares. The V-shaped weir ditch, only covered in a short section at the bottom, pointed a width of 2.8 meters and was still 1.2 meters deep. Its original dimensions could be observed in 1995 during construction work in the course of sewer works. The trench was cut on the southern front of the fort, in Wessenbergstrasse. The original walking level, 8 meters wide and 3.5 meters deep, was still preserved here. The found material recovered from its filling came from the period after AD 260.

Castle III

What is striking is the great similarity between this fort and the neighboring fortress in Stein am Rhein, which, according to its building inscription, was built under Emperor Diocletian around 294. Its defensive towers are strikingly similar in plan and dimensions to the Constance example. It is believed that both forts are based on a common building plan. For the neighboring late Roman forts in Pfyn and Arbon, the founding date is also around 300 AD. The late antique fort covered an area between 0.7 and 1.0 hectares and was oriented towards NNW-SSE. Contrary to previous assumptions that it encompassed the entire Münsterhügel - it extended northwards from its crest to the Niederburg district. Its true dimensions were about 150 meters in north-south direction and 80 meters in west-east direction. The topography of the cathedral hill did not allow the classic, right-angled floor plan, which was also rarely found in late antique castles. This corresponds to the size of the neighboring late antique fortresses in Tasgetium (Stein am Rhein, 0.8 ha), Arbor Felix (Arbon, 0.85 ha) and Ad Fines (Arbon, 1.5 ha). On both sides of the Hussenstrasse, in the course of which the ancient access to the fort is presumed, and below the Stephansplatz, the burial places belonging to the fort have been proven.

Even if the extension of the fortress has not yet been made accessible by excavations, there are some indications for this: To the south it probably did not extend beyond the cathedral, as a study carried out in 1989 on the southern part of the Münsterplatz confirmed. There, however, no remnants of the massive defensive wall were found, as was also the case in the north of Münsterplatz (2003/2004) with regard to the eastern front of the fort. The excavation area extended to the Christ Church which limits the space in the east. The fort wall should have stood here between the excavation boundary and the ancient lake shore that ran 5 to 10 meters east of it. Between 1983 and 1984, further remains of the wall from late antiquity were discovered north of Johanneskirche in Brückengasse. According to the type of building structure and its orientation, they fit seamlessly into the remains of the fort discovered in 2003. In Inselgasse, which runs from east to west, there are currently no signs of late Roman settlement. In summary, the fort ended in the south at the cathedral, further remains of the wall were found in Brückengasse 5/7, to the west it probably extended to St.-Johann-Gasse, in the north the Brückengasse / corner Inselgasse marks the expansion of the late Roman fortress. The walls possibly even extended to what was then the shores of Lake Constance and protected a port (see section Port).

During the excavation at Münsterplatz, the western wall was exposed over a length of around 27 meters. The fort wall, which was still 0.8 meters high and was built using the two-shell technique, was 2.20 meters wide. Outside and inside it was faced with tuff stones, on which the remains of white plaster could still be seen and which were still approx. 80 cm high. It rested on a deep, somewhat broader foundation of mortared Lake Constance rubble. The defense was reinforced - at least in the exposed section - by a defense tower formed from five sides of the octagon, 7 meters wide and around 6 meters in diameter, which - typical of late antique castles - protruded far from the wall. Its 1.2 meter thick masonry was also faced with tuff on both sides. The rising was still preserved up to a height of 1.40 meters. Originally it probably reached a height of 13 meters. It could be entered through a ground-level door at its rear. On the outer front, it ended with a base to a massive, rectangular foundation platform. This particularly strong foundation of the tower was necessary because it stood over a natural channel that had been built up during the previous Roman settlement period, but the filling layers of which did not provide a sufficiently solid base. Despite this measure, settlement cracks formed in the screed floor of the tower, which could be entered at ground level through a 1.20 meter wide door from the inside of the fort.

Thermal bath

Of the interior structures of the late antique fortress, only the stone bathing building has so far been excavated. Large parts of its floor plan have been documented. In contrast to the fort, the bathing building is precisely aligned with NS. There were no soil problems here as with the western intermediate tower, as it was consistently on solid ground. In addition to unheated chambers, it consisted of a 22-meter-long row of three rooms laid out one behind the other, with underfloor and wall heating (so-called row bathroom). The tepidarium (warm bath) and the caldarium (hot bath) were located there. The one at the southern end, round. The 54 m² caldarium was probably equipped with three hot water basins placed in rectangular apses. Two of these apses on the west and south walls could be examined during the excavation. A third was probably on the east side of the caldarium . It was heated by a praefurnium (boiler room) on the south side , which, however, was not built in stone. The hot air flowed through a wide heating channel into the hypocausts of the warm and hot baths. The building findings indicate that the bathroom was rebuilt at least once in the course of late antiquity, possibly reducing its area a little.

garrison

It is not known whether Constance also housed a garrison during the Claudian and Flavian reigns (41–96 AD). Even the new discovery of a fragment of a brick stamp from Legio XI Claudia Pia Fidelis , which was in Vindonissa (Windisch / CH) between 70 and 101 AD , is insufficient as evidence of this. Otherwise nothing is known about the occupations of the 2nd to 3rd centuries AD.

Only the garrison unit of late antiquity has been proven beyond doubt. According to the Notitia dignitatum , an almanac and list of troops, written around 420, the Roman naval unit stationed in Constance and Bregenz was subordinate to a Praefectus Numeri Barcariorum . This troop was part of the army of the Dux Raetiae . Barbaricariorum actually means "gold sticker" (see brocade fabric ). Although several fabricae (arms factories) are mentioned in the Notitia, this seems very unusual as a name for a military unit. As is so often the case with this document, it is likely that the medieval copyists made a typing error. In reality it was probably meant to be a numerus barcariorum . Barcariourum ("boat people") would also be a far more appropriate name for a naval unit. The flotilla should have been stationed at its two locations ( Brigantium headquarters ) until around 402 .

port

In 1943 and 1944, when an air raid shelter was being built on Hofhalde / Pfalzgarten, southeast of Fort III, a wall was found that could be traced over a length of 9 meters. A large amount of Roman ceramics from all centuries of Roman rule over Constance could be found as additional finds. In 1953, when excavating for the Kolping House, another wall with a similar structure was found. Alfons Beck suspects that they belonged to the Roman port that was attached to the border fort. The harbor basin was filled up in the Middle Ages.

Civil settlements

The Celts , presumably from the Helvetii tribe , settled here as early as 120 BC. In the area of today's district of Niederburg. They fortified the area of the cathedral hill with a wood-earth wall and a 7 meter wide and 2.60 meter deep trench. The importance of this Celtic settlement is still disputed. It could have been an insignificant fishing settlement or an oppidum , the latter assumption being based on the occurrence of imported ceramics. It is possible that Sequans also settled here , as Roman sources suggest. The end of the Celtic settlement is also uncertain. Perhaps through events in the first half of the 1st century BC. BC or because of the conflicts in the course of the Roman Alpine campaign .

The Roman settlement was in the north of the Münsterhügel, between the fort and the Rhine on today's Brückenstraße, also called "Niederburg" and "Niederwaserburg" in literature. There were probably three settlement periods in Constance. As excavations show, Romans had already built simple wooden houses on the plateau of Münsterplatz and Niederburg as early as the 1st century BC. This settlement consisted of wood for two construction periods. The first stone buildings were built here in the 2nd century, and the place was fortified twice in the 3rd century. The walls probably served from the 60s or 70s of the third century AD to protect against the increasing attacks of the Alemanni . Apparently a civilian settlement quickly formed around the late Roman fortress - as is usually the case - in this case too, if one did not already exist. The Roman baths not far from the fortress, which also date from the 4th century, are unusually large for this period. The remains of the bath with an inscription plaque are known from this place. It is assumed that a Roman civil and military settlement was inhabited here at least until the Romans retreated in 401/402, after which an already Christianized Roman-Celtic population remained. However, it was assimilated by the Alemanni over the next 200 years.

Note

The findings under the northern Münsterplatz are only accessible to the public through a retractable staircase. In order not to visually impair the redesigned square with a roofed entrance, the castle ruins were made accessible to the public during guided tours as an underground exhibition through a hatch and the “Pyramid am Münsterplatz”, a light shaft. The tour times are indicated on a small board which is right next to the entrance. The most important finds are shown in a permanent exhibition in the Archaeological State Museum Baden-Württemberg in Konstanz.

Timetable

- 1st century v. Chr .: The Celts fortify the area of the Münsterhügel with a wood-earth wall and a moat.

- 1st century AD: The Celtic settlement is destroyed by the Romans and a fort is built in its place, which, however, dates back to the second half of the century. loses its military importance again. A civil settlement is being built on the site of the fort.

- around 300: The late Roman fort is built. It was named after one of the Constantinian emperors.

- around 600: Constance is made a bishopric. In the years that followed, the walled bishop's seat was added to the Roman fort in the south and a fortified craftsmen's quarter in the Niederburg area in the north.

- 9th century: The last remains of the fort's wall are removed.

literature

- Jörg Heiligmann : The Constance Minster Hill. Its settlement in Celtic and Roman times. In: Writings of the Association for the History of Lake Constance and its Surroundings . Volume 127, 2009, pp. 3-24. Thorbecke, Ostfildern, ISBN 978-3-7995-1715-7 .

- Jörg Heiligmann, Ralph Röber: Long suspected - finally proven: the late Roman fort Constantia. First results of the excavation on the Münsterplatz in Konstanz 2003-2004. Baden-Wuerttemberg State Monuments Office, Newsletter 3, 2005.

- Jörg Heiligmann: History of the Lake Constance area in the 3rd and 4th centuries. In: Hasler / Heiligmann / Höneisen / Leuzinger / Swozilek (eds.): In the protection of mighty walls. Late Roman forts in the Lake Constance area. Frauenfeld 2005, ISBN 3-9522941-1-X .

- Jörg Heiligmann: The late Roman fortress Constantia (Constance). In: Hasler / Heiligmann / Höneisen / Leuzinger / Swozilek (eds.): In the protection of mighty walls. Late Roman forts in the Lake Constance area. Frauenfeld 2005, pp. 76-79.

- Jörg Heiligmann, Ralph Röber: Konstanz - Münsterplatz: From legionaries and canons. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg 2004. 2005, pp. 132–136.

- Jörg Heiligmann: Two weir trenches and a well. The results of the 2005 excavation on Münsterplatz in Konstanz. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg 2005. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-8062-2019-0 , pp. 139–142.

- Jörg Heiligmann, Ralph Röber: In the lake - by the lake. Archeology in Constance. Likias, Friedberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-9812181-4-5 .

- Office for Archeology of the Canton of Thurgau: Romans, Alemanni, Christians. Early Middle Ages on Lake Constance. Frauenfeld 2013, ISBN 978-3-9522941-6-1 .

- Robert Rollinger : On Constantius II's Alemanni campaign on Lake Constance and the Rhine in 355 AD and on Julian's first stay in Italy. Reflections on Ammianus Marcellinus 15.4. In: Klio . 80, 1998, ISSN 0075-6334 .

- Bernhard Schenk: The Roman excavations near Stein am Rhein. In: Antiqua. 1883.

- Andreas Kleineberg, Dieter Lelgemann: Germania and the island of Thule. The decoding of Ptolemy's "Atlas of the Oikumene". Darmstadt 2010.

- Ursula Koch: Defeated, robbed, driven out. The consequences of the defeats of 496/497 and 506. In: Archäologisches Landesmuseum Baden-Württemberg (Hrsg.): The Alamannen. Wais & Partner publishing office, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-8062-1302-X .

- Otto Feger (Hrsg.): Constance in the mirror of the times. Constance 1952.

- Hans Stather: Roman Constance and its environment. Stadler, Konstanz 1989.

- Hans Stather: The Roman military policy on the Upper Rhine with special consideration of Constance. Hartung-Gorre, Konstanz 1986.

- Gudrun Schnekenburger: Constance in late antiquity. In: Archaeological News from Baden. No. 56, Freiburg / B, 1997, pp. 15-25.

- Marianne Dumitrache: Constance. Archaeological city cadastre. Tape. 1, Stuttgart 2000.

- Marianne Dumitrache: Fine stratigraphy with Roman finds on the old bank of the Seerhein in Constance. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg 1993. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-8062-1118-3 , pp. 271-273.

- Marianne Dumitrache: Urban archeology in Constance. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg 1994. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1174-4 , pp. 303-311.

- Marianne Dumitrache: News from Roman and Medieval Constance. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg 1995. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-8062-1234-1 , pp. 241-255.

- Ralph Röber: Urbs praeclara Constantia - the Ottonian-Early Salian Constance. In: Barbara Scholkmann, Sönke Lorenz (Ed.): Swabia a thousand years ago. Filderstadt 2002, pp. 162–193.

- Ralph Röber: Konstanz - the late antique fort and the beginnings of the bishopric. In: Archäologische Ausgrabungen in Baden-Württemberg 2003. 2004, pp. 100-103.

- Ralph Röber: From the late Roman fortress to the early medieval bishopric: Constance on Lake Constance. In: Continuity and discontinuity in archaeological evidence. 2006, pp. 13-18.

- Ralph Röber: Urban archeology in Constance. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg 1998. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-8062-1406-9 , pp. 248-251.

- Ralph Röber: Roman and medieval trenches from Constance. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg 2001. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-8062-1659-2 , pp. 188–191.

- Petra Mayer-Reppert: Roman finds from Constance. From the beginning of the settlement to the middle of the 3rd century AD. In: Fund reports Baden-Württemberg. No. 27, 2003, p. 441 ff.

- Timo Hembach: Time of upheaval - the Lake Constance area on the way from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages. In: Hasler / Heiligmann / Höneisen / Leuzinger / Swozilek (eds.): In the protection of mighty walls. Late Roman forts in the Lake Constance area. Frauenfeld 2005, pp. 54-61.

- Gerhard Julius Wais: The Alemanni in their confrontation with the Roman world. Investigations into the Germanic land grab . Ahnenerbe-Stiftung Verlag, 1943, p. 213.

- Hermann Baumhauer: Baden-Württemberg. Image of a cultural landscape . Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1983.

- Ludwig Leiner: The development of Constanz. In: Writings of the Association for the History of Lake Constance and its Surroundings. Volume 11, 1882, pp. 73-92. Digitized

- Ludwig Leiner: New traces of the Romans in the Constanz area. In: Writings of the Association for the History of Lake Constance and its Surroundings. Volume 12, 1883, pp. 159-160. Digitized

- Benno Schubiger: Solothurn. Contributions to the development of the city in the Middle Ages: Colloquium from 13./14. November 1987 in Solothurn. vdf Hochschulverlag AG, 1991, ISBN 3-7281-1806-0 .

- Walter Drack, Rudolf Fellmann: The Romans in Switzerland. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-8062-0420-9 .

- JI Kettler: Journal of Scientific Geography. 1880.

- Walter Schlesinger: Contributions to the German constitutional history of the Middle Ages: Teutons, Franks, Germans. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1963.

- Erich Keyser: German city book: Handbook of urban history. Kohlhammer, 1939.

- Franz Beyerle: The Alemannic campaign of Emperor Constantius II from 355 and the naming of Constantia (Constance). In: Journal for the history of the Upper Rhine. 104, 1956, pp. 225-239.

- Alfons Beck: Constance until the end of Roman rule. In: Badische Heimat. No. 38, 1958.

- Alfons Beck: The Roman fort in Constance. In: Vorzeit am Bodensee. 1961/62, pp. 27-40.

- Gerhard Fingerlin : Constance. In: Dieter Planck (Ed.): The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. Theiss. Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1555-3 .

- Franz Xaver Kraus: The art monuments of the Constance district. Freiburg 1887.

- Münsterbau-Verein: The Old Constance. Constance 1881.

- Harald Derschka : The found coins from Münsterplatz in Constance: the excavation in the area of the late Roman fort and other new finds from ancient times. In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg. No. 36, 2016, pp. 341–362

Remarks

- ↑ See Kettler 1880, p. 137, Heiligmann / Röber 2005, p. 134, Heiligmann 2005, p. 77, Wais 1943, p. 213.

- ↑ Kleineberg 2010, p. 90.

- ↑ Beck 1958, p. 227, Schlesinger 1963, p. 96, Drack / Fellmann 1988, p. 418, Keyser 1939, p. 273, Rollinger 1998, p. 231-262.

- ↑ Leiner 1882, pp. 73–92 and 1883, pp. 159–160, cf. writings of the Association for the History of Lake Constance and its Surroundings 1976, p. 20.

- ↑ See find reports from Baden-Württemberg 1980, p. 186.

- ↑ Heiligmann / Röber 2005, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ See writings of the Association for the History of Lake Constance and its Surroundings . ed. by Association for the History of Lake Constance and Its Surroundings, 1976, p. 22.

- ↑ Beck 1958, p. 227, Koch 1997, p. 196, Römer, Alemannen, Christen. Early Middle Ages on Lake Constance. 2013, pp. 15, 28, Heiligmann / Röber 2005, pp. 139–140, Hasler 2005, p. 56, Schenk 1883, pp. 67–76.

- ↑ Hasler 2005, p. 57, Heiligmann / Röber 2005, pp. 140–141, Schlesinger 1963, p. 96.

- ↑ Hasler 2005.

- ↑ Beck 1958, p. 224, Heiligmann / Röber 2005, pp. 136-137, Heiligmann 2005, p. 77.

- ↑ Heiligmann / Röber 2005, p. 137.

- ↑ Schubiger: 1991, p. 156, Drack / Fellmann 1988, p. 418, Heiligmann / Röber 2005, p. 135.

- ↑ Heiligmann 2005, pp. 77-78.

- ↑ Heiligmann / Röber 2005, pp. 138-139.

- ↑ Heiligmann / Röber 2005, p. 138.

- ↑ distress. Dig. Occ. 35, 32, Praefectus Numeri Barbaricariorum, Confluentibus siue Brecantia , cf. ND Occ. 154.6, Numerus Barcariorum Tigrisiensium .

- ↑ Beck 1958, pp. 230-231.

- ↑ Baumhauer 1983, p. 165, Kettler 1880, p. 137.