Mons Brisiacus

| Fort Breisach-Münsterberg | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Mons Brisiacus, b) Monte Brisiaco, c) Brisiacum, d) Brisaci, e) Brezecha |

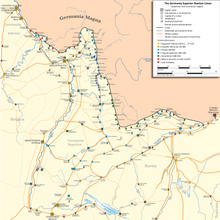

| limes |

Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes , Maxima Sequanorum |

| Dating (occupancy) | Constantinian, early 4th century to early 5th century |

| Type | Cohort fort? |

| unit | Limitanei / Foederati ? |

| size | approx. 3 ha |

| Construction | Stone construction |

| State of preservation | Not visible above ground, irregular system with intermediate towers and a gate tower |

| place | Breisach on the Rhine |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 1 '44 " N , 7 ° 34' 48" E |

| height | 225 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Fort Sasbach-Jechtingen (north / right bank of the Rhine) |

| Subsequently | Argentovaria (southeast / right bank of the Rhine) |

| Backwards | Horbourg Castle |

Mons Brisiacus is a former late Roman fort in the area of the town of Breisach am Rhein in the district of Breisgau-Hochschwarzwald in Baden-Württemberg .

The camp was part of the fort chain of the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes in the section of the Roman province of Maxima Sequanorum and occupied from the 3rd to 4th century AD with Roman troops who were responsible for monitoring the imperial border and road connections. It was located on the plateau of the Münsterberg and had a representative praetorium . In the second half of the 4th century, Emperor Valentinian I coordinated the construction work to strengthen the Rhine Limes (ripa) from here . The fort was possibly used as a refuge until the early Middle Ages.

location

The Breisgau is located between the Upper Rhine and the Black Forest . Breisach itself is four kilometers southwest of the Kaiserstuhl , a volcano that is now extinct. Geologically, the Münsterberg is the southeastern extension of the Kaiserstuhl. It is located on the eastern bank of the Rhine, directly on the German - French border, halfway between Colmar and Freiburg im Breisgau (approx. 20 kilometers) and approx. 60 kilometers north of Basel and south of Strasbourg. The ancient topography has been greatly changed by the repeated destruction of the city, the modern development and the creation of vineyards.

The natural conditions on site are ideal for the construction of a height fortress. The approx. 45 m high Münsterberg, on which the late antique fort stood, is a basalt rock over two kilometers long, rising steeply on the west, east and south sides. Only the north side slopes gently towards the Rhine plain and offered the only way to access its plateau. In ancient times it was surrounded by two arms of the Rhine on all sides. Liutprand von Pavia reports that the Münsterberg was still like an island in the Rhine in the 10th century. The ramified river offered additional protection, as its course changed after each major summer flood. This only came to an end when Johann Gottfried Tulla tackled the regulation of the Rhine in the early 19th century.

Surname

The ancient name of Breisach may have developed from the Celtic personal name * Brîsios with the suffix -āko (> -acum). Mons Brisacus could also refer to the island location of the Münsterberg at that time, bris = break or brisinac "water breaker " or "the rock mountain on which the water breaks".

In the ancient sources, the Mons Brisiacus im

- Itinerarium Antonini (3rd century) mentioned in three places (Monte Brisiaco) , in

- Codex Theodosianus , decree Valentinians I of 369 and at

- Geographer of Ravenna who called the place Brezecha in the 8th century .

function

North of Mons Brisiacus was the border between the provinces of Germania I and Maxima Sequanorum in late antiquity . An important east-west trunk road ran along this border, coming from the direction of Metz , crossing the Vosges and reaching the banks of the Rhine via Horburg and Argentovaria . This street crossed with the Limesstraße on the left bank of the Rhine, which ran from north to south. Together with the garrisons in Argentovaria , Horbourg and that of the fort on the Sponeck , the Breisach garrison was primarily supposed to monitor and maintain these roads. In addition, the Rhine played a major role as a transport route at that time. Due to its prominent location directly on the river, the fort crew probably also controlled the shipping traffic. Presumably there was also a bridge over the Rhine near Breisach.

Research history

Only the area between the cathedral and the town hall has been well researched, around 15% of the Münsterberg plateau. Numerous small finds bear witness to the, in some cases, luxurious lifestyle of its residents. The first known excavations came to light 200 years ago. In 1891, a hoard made of Roman copper coins came to light near the wheel fountain. In the early 20th century, the prehistorian Karl Gutmann explored the Roman roads around Breisach. In 1914, Roman shards of vessels came to light between the district court and the rectory, but - without having examined them beforehand - they were quickly disposed of with the rubble. As one of the few early Iron Age “princely seats” north of the Alps, the plateau was excavated from the 1930s onwards and revealed a large number of settlement findings. Between 1937 and 1938, Rolf Nierhaus first searched systematically and according to scientific methods for the fort. In 1969 and 1975, Gerhard Fingerlin (Landesdenkmalamt) and Hans Bender examined the site. The two largest excavation campaigns to date took place between 1980 and 1986 in the area of Kapuzinergasse and during construction work to expand the town hall. Here were a number of Late Hallstatt and Early Latène documented and Roman finds and evaluated. Ceramic artifacts made up the largest proportion of the approximately 1000 kg of finds from a total of 127 pits and other other settlement structures. The Roman finds are mainly imports from the provinces of the Mediterranean region. From 2005 to 2007, Hans Ulrich Nuber and Marcus Zagermann (Department of Provincial Roman Archeology at the University of Freiburg) dug on the Münsterberg.

development

Breisach can look back on a very long history of settlement. The first human traces on the Münsterberg plateau go back over 3000 years to the Neolithic Age . For the time around 1200 BC A larger settlement and ceramic fragments of the urn field culture could be proven. During the Celtic rule over this area there was a princely seat of the Sequani , whose trade contacts extended to the Mediterranean.

Turn of time to the 3rd century

The region around Breisach has probably been around since 58 BC. BC to the Roman sphere of influence, when Gaius Iulius Caesar defeated the Germanic tribes under Ariovistus near Mühlhausen and drove them out of Alsace . From 15 BC After the Alpine campaign of Augustus , the Rhine and Danube became the new frontier of the empire.

After the abandonment of the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes , the Romans withdrew again behind their old borders on the Rhine and Danube. At that time the banks of the Upper Rhine were covered by dense alluvial forests and the river itself branched out into several tributaries that constantly changed their course. In order to effectively secure the new old border, a large number of military facilities and the associated infrastructure had to be built here again. One of them was the fort on the Münsterberg. Until then, Mons Brisiacus had not played a significant role in defending the border. Traces of civilian settlement during the early or middle imperial period could not be found either. If there was such a settlement in the vicinity of the Münsterberg, it can only have been of regional importance. After the first great Alemanni incursions around 260, the Romans initially only built a temporary fortification on the easily defended plateau.

4th to 5th century

Under Constantine I , it was expanded into a larger fort in the first half of the 4th century. In the middle of the 4th century the Alemanni burned it down, but it was quickly repaired afterwards. In the late 4th century a comprehensive reorganization and reinforcement of the border defense had become necessary, as the Alamanni under their military leader Rando 368 even attacked and plundered the provincial capital of Germania I , Mogontiacum .

This was done by building and strengthening watchtowers (on the Upper Rhine), small burgi and forts under Emperor Valentinian I (364–375 AD). The Constantinian fort, from where the ruler of the western part of the empire started, was also rebuilt 369 who probably personally organized the construction work on this section of the Limes took place at this time. It is proven that some new buildings for the Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes were started around 370 in the province of Maxima Sequanorum . B. in Koblenz and Etzgen in Aargau (two watchtowers with building inscriptions,) Aegerten-Isel and Aegerten-Bürglein (AG). The history of Ammianus Marcellinus shows that Valentinian supervised the construction work on the Rhine Limes with great personal commitment. As a result, Breisach is the only Roman town in Baden-Württemberg to be able to claim a documented stay for one of the most important emperors of late antiquity. When Valentinian set up his headquarters for a few days on Mons Brisiacus , the fort became the residence and administrative center and thus the center of the Western Roman Empire. From here, on August 30, 369, Valentinian issued a rescript (reply) addressed to the Praetorian Prefect Sextus Petronius Probus , in which he fully confirmed their retirement payments to his court officials (palatini) . Apparently the fort had the necessary infrastructure to be able to supply and accommodate an entire court. Today there is no longer any doubt in the professional world that the emperor and his immediate entourage (comitatus) were housed in the praetorium .

After the withdrawal of the Roman army and subsequent occupation by the Alemanni in the period after 400, the fort was partially destroyed. It may also have been the scene of an episode of the Hamelungen or Nibelungen saga . At the time of Attila , a king named Amelung allegedly ruled over the Rhine plain from the "Fritaliburg". Around the middle of the 5th century, the fort probably came into the possession of a Frankish king.

Post-Roman times

In 938 Heinrich the Quarrel was besieged on the Münsterberg by the troops of Emperor Otto I and the place was called castellum munitissimum (= a particularly strong fortified castle) in contemporary chronicles , which could mean that at least the fort walls were still intact at that time . It may have served as a retreat for the people who settled in the surrounding area until the second half of the 13th century in times of crisis.

Fort

No remains of the fort are visible above ground today. It presumably existed from the first half of the 4th century to the early 5th century. Unusually for the Roman forts on the Upper Rhine, the camp was located at a prominent altitude with a good view in all directions. Similar to the fort in Kellmünz / Caelius Mons, it was a fortification with a solid wall (see shield wall ) on the naturally unprotected side and a relatively narrow wall with intermediate towers set up in different sections along the steep slopes. The complex also had an irregular ground plan, largely adapted to the 500 m × 200 m mountain plateau, took up its entire southern half and covered an area of approximately three hectares.

Enclosure

North wall : This 200 m long and probably three meters wide and eight meters high wall ran from west to east, about 130 m south of the location of the wheel well tower. It sealed off the highest elevation of the Münsterberg plateau in its entire width from the only access from the north. Only the 3.30 m wide foundations sitting directly on the grown loess soil remained of it. On the west side they were 1.80 m to 2 m below today's street level, on the east side only the foundation trenches were detectable. They consisted of mortared sand and volcanic rubble, which were probably extracted from quarries in the nearby Kaiserstuhl or the Münsterberg itself. Demolition material was also used to build the north wall, such as B. Broken roof tiles / tegulae . The mortar consisted of lime mixed with pebbles. Under the foundation, irregularly placed, 1.3 m long (15 cm to 20 cm in diameter), round or square wooden stakes were found, which had been rammed into the loess soil in pairs at a distance of 55 cm to 90 cm.

Walls accompanying the slope: with a width of 1.9 m to two meters, they were constructed significantly less massive than the north wall, as no attacks were to be feared from the steeply sloping south, west and east sides of the cathedral hill. During excavations on the occasion of a new hotel building, a section could still be traced over a length of 14 m. In the south, however, nothing was left, its course could only be recognized by means of traces of processing in the rock.

Towers and fort gate

A square, probably semicircular, 4.15 m wide intermediate tower (horseshoe tower) with walls 5.50 m thick could be detected on the northern front. He jumped 1.90 m outwards and 0.30 m inwards. There were almost certainly more of these towers on the north wall. On the eastern edge of the Münsterplatz there was evidence of another horseshoe tower from 1969-1970. Directly opposite, in the west of the plateau, there was probably an identical copy. The towers were probably not lined up on the walls at exactly the same distance.

In the center of the north wall (Radbrunnenstraße) the fort gate - or its western gate cheek - could be partially excavated. Their length was 8.20 m. It was partially preserved up to a height of one meter. The construction of the gate is comparable to that of Fort Altrip .

Weir trenches

Two trenches had been dug in front of the wall as obstacles to approach . The width of the berm was - in contrast to comparable systems - small and was only 8 m to 8.50 m. The inner trench was approximately 11 to 13 meters wide and four meters deep. After about four meters, a second, somewhat narrower, nine to ten meters wide trench followed. The dimensions could not be determined exactly because the trenches z. T. had been sunk into the natural rock. It is possible that there was also a smaller ditch directly in front of the fort wall, but this is still controversial.

Interior development

The level of the inner surface was artificially raised by filling in the debris. A natural incision that originally divided the plateau in half had already been filled in by the Celtic settlers of the La Tène period. The remains of two extensions could be observed on the western wall. The north-south running camp main street led from the Praetorium directly to the north gate and continued outside the fort walls in today's Radbrunnenallee.

Praetorium: The interior area was dominated by an approx. 1500 m² large, representative building in the extreme south of the plateau. The remains of the foundations stretched across the entire forecourt of St. Stephen's Cathedral. According to Hans Ulrich Nuber, it was a so-called praetorium , an administration and accommodation building for state officials, in which Emperor Valentinian I was almost certainly also housed - during his stay in the fort for several days. Today it is largely overbuilt by the cathedral. The building complex was divided into two parts. The rooms of the multi-storey main wing were grouped on three sides around a small inner courtyard, which was closed off in the north by a wall with a passage. The second part consisted of a second courtyard, set slightly to the west, bordered by a larger single-storey building in the east and a smaller building in the west. In the north it was closed off by a wall with a gate through which one could enter the praetorium itself and a small bathroom.

garrison

Soldiers from the castles Castrum Rauracense / Kaiseraugst and Argentorate / Strasbourg were presumably assigned to build the fort , as the brick stamps found in Breisach suggest. In 1853 Heinrich Meyer reported on the discovery of a brick temple by the Legio XXII Primigenia stationed in Mainz . The Legio I Martia is also documented by brick stamps in the first half of the 4th century - as the border protection force responsible for the section on the Upper Rhine. The camp was probably manned by a vexillation of this legion, which belonged to the army of the Dux provinciae Sequanicae responsible for this border section ( tractus) . In the early 5th century the garrison may have been under the command of the Comes tractus Argentoratensis . Ceramic finds suggest the presence of Alemannic mercenaries. From the Notitia Dignitatum are also two auxiliary units ; the

- Brisigani seniores , stationed in Hispania (Army des Comes Hispaniarum ) and the

- Brisigani iuniores , who were garrisoned in Italy,

known. They are likely to have been erected between 395 and 398 under Emperor Honorius and were composed for the most part of warriors from the Breisgau-Alamanni. They were possibly descendants of the troop contingent that the Alemanni kings Gundomadus and Vadomarius had to make available to the Roman army after the lost battle of Argentorate in 357. In 1843 a Roman funerary inscription was discovered in the foundations of a house for the soldier Saturninus. The age information is presumably incomplete, the part indicating the troop membership was missing. The stone is lost today.

Monument protection

The ground monument is a registered cultural monument within the meaning of the Monument Protection Act of the State of Baden-Württemberg . Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to approval, and random finds are to be reported to the responsible authorities.

Note

The history of the Roman Breisach, which is important for the entire Upper Rhine, has recently been brought to the fore in the Museum of City History (Museum in the Rheintor) through the redesign of the Roman exhibition. This was significantly expanded, equipped with numerous new finds and redesigned. In the new exhibition it becomes clear that the late Roman fort of Breisach was not only of importance for military purposes, but also for the imperial administration as a traffic junction on the Upper Rhine.

See also

literature

- Rolf Nierhaus: On the topography of the Münsterberg von Breisach. In: Baden find reports. 16, 1940, pp. 94-113.

- Rolf Nierhaus: Excavations in the late Roman fort on the Münsterberg in Breisach in 1938. In: Germania. 24, 1940, pp. 37-46.

- Günther Haselier: History of the City of Breisach. From the beginning to the year 1700. 1st half volume, self-published by the city of Breisach am Rhein, 1969.

- Gerhard Fingerlin: Borderlands in the Migration Period. Early Alemanni in Breisgau. In: Archaeological State Museum Baden-Württemberg (Hrsg.): The Alamannen. [Accompanying volume for the exhibition The Alamanni; June 14, 1997 to September 14, 1997 SüdwestLB-Forum, Stuttgart, October 24, 1997 to January 25, 1998, Swiss National Museum Zurich, May 6, 1998 to June 7, 1998, Roman Museum of the City of Augsburg]. Theiss, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-8062-1302-X , pp. 103-110.

- Lothar Bakker: Bulwark against the barbarians. Late Roman border defense on the Rhine and Danube. Archaeological State Museum Baden-Württemberg (Hrsg.): The Alamannen. [Accompanying volume for the exhibition The Alamanni; June 14, 1997 to September 14, 1997 SüdwestLB-Forum, Stuttgart, October 24, 1997 to January 25, 1998, Swiss National Museum Zurich, May 6, 1998 to June 7, 1998, Roman Museum of the City of Augsburg]. Theiss, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-8062-1302-X , pp. 111-118.

- Helmut Bender: The Münsterberg in Breisach 1. Roman times and early Middle Ages Carolingian-Pre-Staufer times. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-10756-7 .

- Marcus Zagermann: The Breisacher Münsterberg. The fortification of the mountain in late Roman times. In: Heiko Steuer (ed.): Hill settlements between antiquity and the Middle Ages from the Ardennes to the Adriatic. de Gruyter Berlin, 2008, pp. 165-183.

- Ines Balzer: Chronological-chorological investigation of the late Hallstatt and early La Tène period "princely seat" on the Münsterberg of Breisach (excavations 1980–1986), regional council Stuttgart - State Office for Monument Preservation, Tübingen 2009, ISBN 978-3-8062-2298-2 .

- Marcus Zangermann: The Münsterberg in Breisach III. The Roman Age findings and finds from the excavations at Kapuzinergasse (1980–1983), city hall expansion, new underground car park (1984–1986) and the construction-accompanying investigations on Münsterplatz (2005–2007). CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-10761-0 .

- Lars Blöck, Andrea Bräuning: New outcrops for the late Roman fortifications on the Breisach Munsterberg - The Breisach Kettengasse excavation 2006-41. In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg. 32, 2, 2011, pp. 339-357, doi: 10.11588 / fbbw.2012.2.26535 .

- Holger Wendling: The Münsterberg of Breisach in the late Latène period. Settlement archeological studies on the Upper Rhine. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-8062-2700-0 .

- Gerhard Fingerlin: Excavations in the late Roman fort Breisach. In: Preservation of monuments in Baden-Württemberg. 1st year 1972, No. 4, pp. 7-11. ( PDF; 8.7 MB )

Remarks

- ↑ Mundt 2008, p. 319; Zagermann 2009, p.?.

- ^ Albrecht Greule : Celtic place names in Baden-Württemberg. In: Imperium Romanum. Rome's provinces on the Neckar, Rhine and Danube. Stuttgart 2005, p. 82; Pierre-Yves Lambert , La langue gauloise , éditions errance 1994. After Albert Dauzat , Charles Rostaing , in Dictionnaire étymologique des noms de lieux en France. Larousse, Paris 1968, and François de Beaurepaire in Les noms des communes et anciennes paroisses de l'Eure. Picard, Paris 1981 have Brizay ( Département Indre-et-Loire , Brisiacum 1050); Brézay and Brézé have the same origin.

- ↑ Codex Theodosianus 6, 35, 8; Rescript of August 30, 369 [1] .

- ↑ 4, 26 (p. 231, 9 ed. Pinder / Parthey) [2] .

- ↑ Zagermann 2008, pp. 165-183.

- ↑ Haselier 1969, pp. 24-40.

- ↑ CIL 13, 11537 and CIL 13, 11538 .

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus 28, 2, 1-4.

- ↑ Codex Theodosianus 6, 35, 8: Ad Probum p (raefectum) p (raetorio): Circa palatinos nostros quies illibata permaneat quo intellegant cuncti nec officia impunitum habere nec iudices si inquietentur hi quibus post documenta fidelitas obsequii subnillostris acta. Brisaci III Kalendas Septembris cosulibus Valentiniano nobillissimo puero et Victore. Translation: “As far as our court officials are concerned, their retirement should remain undiminished; Let it be seen by everyone that neither authorities nor judges will go unpunished when harassing those who, in our opinion, must be given evidence of faithful obedience and rest in full measure. Given to Breisach, to the III. The end of September when noble Valentinian and Victor were consuls. "

- ↑ Zagermann 2008, pp. 165-183.

- ↑ Günther Haselier 1969, pp. 24–42; Christel Bücker: The Breisacher Münsterberg. A central place in the early Middle Ages. In: Heiko Steuer (ed.): Hill settlements between antiquity and the Middle Ages from the Ardennes to the Adriatic. de Gruyter, Berlin 2008, pp. 185–209, here pp. 189–190.

- ↑ Zagermann 2008, pp. 165-183.

- ↑ Zagermann 2008, pp. 165-183.

- ↑ Zagermann 2008, pp. 165-183.

- ↑ Zagermann 2008, pp. 165-183.

- ↑ Zagermann 2008, pp. 165-183; [3] .

- ^ Heinrich Meyer: History of the XI. and XXI. Legion. (= Communications from the Antiquarian Society in Zurich. Volume 7, Issue 6). Zurich 1853.

- ↑ (Saturninus Boudill [i filius] a [nnorum] [L] XXX)

- ↑ CIL 13,5332 ; Bakker 2001, pp. 103, 114