Otto I (HRR)

Otto I the Great (* November 23, 912 ; † May 7, 973 in Memleben ) from the House of Liudolfinger was from 936 Duke of Saxony and King of the East Frankish Empire (regnum francorum orientalium) , from 951 King of Italy and from 962 Roman -German Emperor .

During the first half of his long reign, Otto enforced the indivisibility of the kingship and his decision-making power in the allocation of offices. In doing so, he intervened deeply in the existing power structure of the nobility . The most serious insurgency movements came from the members of the royal family themselves. Otto's brother Heinrich and his son Liudolf claimed participation in the kingship. Otto emerged victorious from each uprising.

His victory over the Hungarians in the Battle of Lechfeld in 955 not only ended their invasions, but also the uprisings of the greats of the empire against the king. In addition, he gained the reputation of a savior of Christianity, especially since he defeated the Slavs in the same year . As a result, a cultural heyday began, which became known as the Ottonian Renaissance .

In 961 he conquered the Kingdom of Italy and expanded his empire north, east and as far south as Italy, where he came into conflict with Byzantium . Nevertheless, he allowed himself to be persuaded by Pope John XII in 962, using Charlemagne 's ideas as emperor . crowned emperor in Rome, and finally he even managed to reach an agreement with the Byzantine emperor and had his son Otto II marry his niece Theophanu .

In the year 968 he founded an archbishopric in Magdeburg , the city that is associated with his afterlife like no other. For Otto, the archdiocese was the decisive prerequisite for the Christianization of the Slavs.

The nickname "the Great" has been a fixed name attribute since the medieval historian Otto von Freising at the latest. Already Widukind von Corvey called him totius orbis caput , the "head of the whole world".

Life

heir to the throne

Otto was born in Wallhausen in 912 as the son of the Saxon Duke Heinrich I , who became king of East Francia in 919, and his second wife Mathilde . Mathilde was a daughter of the Saxon Count Dietrich of the Widukinds family . From Henry I's annulled first marriage, Otto had the half-brother Thankmar . Otto's younger siblings were Gerberga , Hadwig , Heinrich and Brun . Nothing is known about his youth and upbringing, but his training may have been shaped by the military. Otto gained his first experience as a military leader on the eastern border of the empire in the fight against Slavic tribes. At the age of sixteen, Otto fathered a son , Wilhelm , with a noble Slavic woman, who later became Archbishop of Mainz .

After the death of Conrad I , who did not succeed in incorporating the greats of the empire into his rule, in 919, for the first time, the kingship was not transferred to a Frank but to a Saxon . Heinrich was only elected by the Franks and Saxons, but through a skilful policy of military submission and subsequent friendships, including numerous concessions ( amicitia and pacta ), he was able to cede the duchies of Swabia (919) and Bavaria (921/922) . to commit. In addition, Henry succeeded in rejoining Lorraine , which had joined the kingdom of West Francia in Conrad's time , with the kingdom of East Frankia (925).

In order to ensure his family's rule over the East Franconian Empire and its unity at the same time, a preliminary decision was made in favor of Otto's sole succession to the throne at least in 929/930. In a document addressed to his wife dated September 16, 929, the so-called "House Rules", Heinrich determined the widow's estate for Mathilde with Quedlinburg , Pöhlde , Nordhausen , Grone and Duderstadt . All the greats of the empire and his son Otto were called upon to recognize and support this "testament". The youngest son, Brun, was handed over to Bishop Balderich of Utrecht to be raised and thus prepared for a spiritual career. In a memorial book of the Reichenau monastery , Otto is referred to as rex (king) as early as 929, but not his brothers Heinrich and Brun. With the title rex , however, Otto was not yet installed as a co-king. There is no evidence of a ruler's activity in the period between 929 and 936, in fact Otto is not mentioned at all in the sources during this period.

Heinrich's succession plan excluded not only non-Saxon candidates but also Otto's brothers. It was significant because Henry abandoned the principle of the Carolingian division of power, which had given each member of the royal house an entitlement. He thus justified the individual succession, the indivisibility of the kingdom and thus of the empire, which his successors were to retain.

At the same time as the preparations for the coronation were being made, the Ottonians were courting the English royal family for a bride for Otto. In this way, Henry endeavored to tie dynasties outside his realm to his house, which had been unusual in the East Frankish realm up to that point. In addition to the additional legitimation through the connection with another ruling house, this reflected a strengthening of "Saxonism", since the English rulers referred to the Saxons who emigrated to the island in the 5th century. In addition, the bride brought with her the prestige of coming from the family of Saint Oswald , who died as a martyr king . After the English king Æthelstan 's two half-sisters Edgith and Edgiva traveled to the court of Henry I, Edgith was chosen as Otto's bride. Her sister married the West Frankish King Charles III. the simple . After Otto's marriage, his Anglo-Saxon wife Edgith received Magdeburg as a dowry in 929 . At Pentecost 930, Heinrich presented the designated heir to the throne in Franconia and in Aachen to the magnates of the respective region in order to obtain their approval for his succession to the throne. According to a note from the Lausanne Annals compiled in the 13th century, which is proven to come from a 10th-century source, Otto was anointed king in Mainz as early as 930. In the early summer of 936, the existence of the empire was discussed in Erfurt (de statu regni) . Henry again strongly recommended Otto as his successor to the greats.

accession

After the death of Henry I on July 2, 936, his son Otto succeeded him within a few weeks, as Widukind von Corvey wrote a good 30 years later. It is possible that Widukind projected details of Otto II's election of a king back in 961 to 936. Widukind's detailed account is currently being discussed in almost every detail. Otto is said to have been elected chief by Franks and Saxony (elegit sibi in principem) and the Palatinate Aachen to have been designated as the place of a general election (universalis electio) . On August 7, 936, the dukes, margraves and other worldly greats placed Otto on the throne in the vestibule of the Aachen Minster and paid homage to him. In the midst of the church the assent of the people to the elevation of the king was obtained. The insignia (sword with sword belt, bracelets and coat, scepter and staff) were handed over by the Archbishop of Mainz, Hildebert von Mainz . Otto was anointed and crowned East Frankish king by the archbishops Hildebert of Mainz and Wichfried of Cologne in the collegiate church . The act of anointing marked the beginning of a multitude of spiritual acts that bestowed on the kingship that sacred dignity which his father had humbly renounced.

By choosing the place for the coronation and consciously wearing Frankish clothing at the ceremony, Otto continued the Franconian-Carolingian tradition of kingship. The election and coronation site in the Lorraine part of the empire was not only intended to emphasize Lorraine's new affiliation with the East Franconian Empire, but as Charlemagne's burial place, Aachen was also a symbol of continuity and legitimacy. At the banquet that followed, the court offices were held by Dukes Giselbert of Lorraine as chamberlain , Eberhard of Franconia as steward , Arnulf of Bavaria as marshal and Hermann of Swabia as cupbearer . By assuming this service, the dukes symbolized cooperation with the king and thus showed quite clearly their subordination to the new ruler. There are no older models for the coronation meal with the symbolic service of the dukes. The rise of the king was divided into spiritual and secular acts. The importance of the sacral-divine legitimation and the increased claim to power over his father also becomes clear in the change in the symbols of power. He continued the East Frankish type of the seal, which shows a military leader favored by God. From 936, however, the divine grace formula DEI Gratia is inserted into the inscription of the royal seal.

rise to power

Despite his designation, Otto probably did not begin his reign as amicably and harmoniously as Widukind's report suggests; Even before the coronation, the ruling family seems to have been at odds, since Otto's brother Heinrich had also claimed the kingship, as reported by the West Frank Flodoard von Reims . Heinrich, as a king's son, probably prided himself on the fact that the documents named him and his father as equivocos (“bearers of the same name”) shortly after birth. During Otto's coronation, Heinrich remained in Saxony under the supervision of Margrave Siegfried . The relationship between Otto and his mother also seems to have been strained. Mathilde was probably not present when her son Otto was made king, as she was still in Quedlinburg on July 31. The lives of Queen Mathilde tell us that Otto's mother would have preferred her younger son Heinrich to succeed him to the throne. In contrast to Otto, Heinrich was born "under the purple" , i.e. after the coronation of Heinrich I, which meant a higher dignity for her.

Five weeks after ascending the throne, Otto rearranged the widow's estate for his mother Mathilde in Quedlinburg . A deed of foundation dated September 13, 936 withdrew Mathilde from Heinrich I's pledged control over the Quedlinburg Abbey she had founded in favor of royal protection. Otto secured his descendants in the deed the power of disposal over the monastery "as long as they hold the throne with a powerful hand". Initially, one's own brother and his descendants were excluded from the claim to the bailiwick of Quedlinburg, as long as a man from the descendants (generatio) of Otto in "Franconia and Saxony" attained the royal office. At the same time, Otto established Quedlinburg as a place of memoria for his ruling family and made it the most important place for the Ottonians in their Saxon heartland. Thus, on the king's first visit to his father's grave, Otto demonstrated the "individual succession" and leadership within the Ottonian family. On September 21, 937, Otto increased Magdeburg's ecclesiastical rank by founding the Mauritius Monastery. In his founding charter, Otto gave the monks the task of praying for the salvation of his father, his wife and children, himself and all those to whom he owed prayers.

Disputes within the royal family and in the empire

Otto's beginning of rule was accompanied by a severe crisis, the cause of which is reported differently by Widukind of Corvey and Liudprand of Cremona . Liudprand relied on rumors and anecdotes circulating at court that defamed Otto's opponents. He cites two causes: on the one hand, Henry's lust for power, who felt disadvantaged by his brother's sole successor, on the other hand, the ambitions of Dukes Eberhard and Giselbert. Both are accused of wanting to become kings after eliminating first Otto and then their allies.

Widukind, on the other hand, reports that Otto ignored the claims of powerful nobles when filling the offices. After the death of Count Bernhard from the Billunger family at the end of 935, Otto occupied the post of army commander (princeps militae) instead of Count Wichmann with his younger and poorer brother Hermann Billung , although the passed-over Wichmann also had a sister of the queen who had died by then Mathilde had been married. In doing so, Otto had significantly altered the hierarchy in the affected noble family. In 937, Siegfried von Merseburg , secundus a rege ( the second man after the king), died in Saxony. Otto awarded Siegfried's command of the southern part of the Saxon-Slavic border to Gero . With Gero, a younger brother of the late Count Siegfried was appointed, although Otto's half-brother Thankmar was related to these counts through his mother Hatheburg and, as the king's son, believed he had more justified claims to the successor.

Also in 937 died the Bavarian duke Arnulf , who with Henry I's approval had reigned almost like a king in Bavaria. Out of arrogance, his sons scorned to go into the king's entourage on the king's command, if one is to believe Widukind 's topical representation in this regard. Eberhard , designated by his father and elected new duke by the Bavarian nobles, refused to pay homage to Otto in 937, after Otto had only wanted to acknowledge Eberhard if he had been willing to renounce the investiture of the bishops in Bavaria. After two campaigns, Otto Eberhard was able to banish; the duchy was awarded to Arnulf's brother Berthold , who renounced both the bishop's investiture and the old Carolingian royal estate in Bavaria and remained loyal to Otto until his death in 947.

Meanwhile, in the Saxon-Franconian border area, Duke Eberhard von Franken , brother of the former King Konrad I, had won a feud with the Saxon vassal Bruning. In the course of this he had burned down the enemy castle Helmern . This castle was in Hessengau , where Eberhard exercised the power of counts . Since Otto did not tolerate Eberhard as an autonomous intermediary, he fined Eberhard to deliver horses worth £100. Eberhard's helpers were sentenced to the ignominious punishment of carrying a dog on a stretch to the royal city of Magdeburg.

These messages are supported by the findings of the memorial book entries. Under Henry I there were a striking number of entries, and the ruling structure at the time was based to a large extent on cooperative ties between the kingdom and the high nobility. On the other hand, the memorial sources dry up completely in the first five years of Otto's reign. While the time of Henry I is described under key terms such as "peace" (pax) and "unity" (concordia) , under his son "quarrel" (contentio) , "discord" (discordia) and "outrage" (rebellio) are im Foreground.

Uprising in the Empire 937–941

Right at the beginning of his reign, Otto's policies snubbed powerful nobles in Saxony, Franconia, Lorraine and Bavaria, who soon rebelled against the ruler: "The Saxons lost all hope of being able to continue to appoint the king," writes Widukind, explaining the seriousness of the situation to characterize.

The Franconian duke Eberhard and Count Wichmann the Elder from the Billunger family allied themselves with Thankmar. He went against Belecke Castle near Warstein in the Arnsberg Forest and delivered the imprisoned half-brother Heinrich to Duke Eberhard. But the fight continued unhappily for the insurgents. Duke Hermann of Swabia , one of the insurgents, defected to King Otto. After Wichmann had been reconciled with the king and Thankmar had been killed in the church of Eresburg after the liberation of Heinrich , Eberhard was isolated and no longer the undisputed leader even within his own clan , so that he resorted to the mediation of Archbishop Friedrich von Mainz dem king subdued. After a brief banishment to Hildesheim , he was pardoned and soon restored to his former dignity.

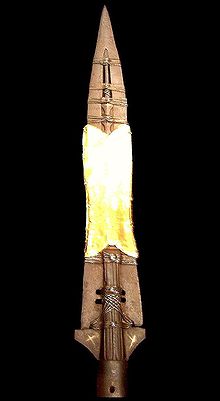

Even before his submission, Eberhard had prepared a new alliance against Otto by promising his younger brother Heinrich that he would help him to the crown. The third ally was Duke Giselbert von Lorraine , who was married to Otto's sister Gerberga. Although Otto initially achieved a victory in a battle at Birten near Xanten , which was attributed to his prayer before the Holy Lance , he was unable to capture the conspirators and unsuccessfully besieged the fortress of Breisach . Archbishop Friedrich von Mainz and Ruthard von Strassburg tried to mediate between Eberhard and the king; when Otto did not accept the mediators' proposal, they joined the opponents. Meanwhile, Giselbert and Eberhard devastated the lands of noblemen loyal to the king. However, the uprising collapsed more or less by accident and without any direct involvement of Otto: in 939, after a plundering expedition into the territories of two of Duke Hermann von Swabia’s followers, Eberhard and Giselbert were surprised by an army led by the Konradines Udo and Konrad while crossing the Rhine near Andernach and in defeated in the Battle of Andernach on October 2, 939. The two rebellious dukes lost their lives: Eberhard was killed, Giselbert drowned in the Rhine. The opponents of the king found it difficult to continue the conflict against this ordeal of God, which was obvious to contemporaries . Henry submitted and received the Duchy of Lorraine, vacated by Giselbert's death, from Otto in an attempt to give him a share in power. As compensation, Otto kept the Duchy of Franconia, which had also become vacant, under direct royal rule. From now on, Francia et Saxonica (Franconia and Saxony) formed the heart of the empire.

In the meantime, Margrave Gero had defended the border against the Slavs at the expense of numerous victims and subdued the area up to the Oder . The Slavs are said to have even planned an attack on the Margrave; However, he came before them and had 30 Slav princes killed after a convivium (banquet) in their weeping sleep. Since the Saxon princes complained that the booty and tribute was too low in view of the high losses caused by the long-lasting campaigns, they came into conflict with the margrave. Her displeasure was also directed at Otto, who supported the margrave. Otto's brother Heinrich took advantage of this mood in the Saxon nobility, so that many of them took part in the conspiracy against the king. At the beginning of the year 939 he organized a big feast or banquet (convivium) in Saalfeld , Thuringia , "there he presented many with large goods and thereby won a crowd to comrades in his conspiracy". Otto was to be murdered on Easter 941 in the royal Palatinate of Quedlinburg at the grave of their father, and a powerful oath (coniuratio) was ready to crown his younger brother afterwards. But the king found out about this plan in good time, protected himself during the festivities by surrounding himself day and night with a band of loyal vassals, and then suddenly launched a counterattack. Heinrich was arrested in the Palatinate Ingelheim , his allies were arrested and mostly executed. However, Heinrich was able to escape from prison and submitted to his brother at Christmas 941 in the Palatinate Chapel in Frankfurt . So he received pardon again, for which he begged barefoot and on his feet. From now on there is no record of Heinrich's attempt to contest the rulership of his brother.

aristocratic politics

When filling offices and possessions, Otto wanted to assert his sovereign decision-making power and did not seek the necessary consensus with the big names when making his decisions. He particularly disregarded the claims of dukes and close family members to certain positions of power. Otto, on the other hand, promoted members of the lower nobility who were devoted to him to key positions in order to secure the status quo in Saxony, and made his mother's faithful feel disadvantaged. Finally, the new king also demanded subordination from his father's “friends”, “who would never have refused them anything”.

Other reasons for the nobility were the still unfamiliar individual succession or succession to the throne, from which the initially unresolved question arose as to how the king's brothers were to be cared for, as well as Otto's authoritarian style of government in comparison to his father. Henry had renounced the anointing that would have symbolically raised him above the greats of the empire, and based his reign on pacts of friendship with important people. These pacts had been an essential basis of Henry I's conception of rulership, who had renounced royal prerogatives in order to achieve internal consolidation in agreement with the dukes. The anointed Otto believed he could make his decisions regardless of entitlements and independent of the internal hierarchy of the noble clans, since his conception of royalty, unlike his father's, placed him far above the rest of the nobility.

The structural peculiarities of the disputes included in particular the "rules of the game for conflict resolution", i.e. the social norms that applied in the high-ranking society of the 10th century. Only the king's opponents from the nobility and his own family, who publicly admitted their guilt and submitted unconditionally, could hope for pardon. The punishment assigned to the king was then regularly so mild that the penitent was soon back in office and with dignity. First in Lorraine and then in Bavaria, the king's brother Henry was given the position of duke. Ordinary conspirators, on the other hand, were executed.

Decade of Consolidation (941–951)

The decade that followed (941-951) was characterized by an undisputed exercise of royal power. Otto's documents from this period repeatedly mention rewards that loyal vassals received for their services or that served to provide for their dependents. From the years 940-47 alone, 14 favors of this kind are known. There are also two diplomas in which goods confiscated by the court were returned. The established royal rule also developed fixed habits of representation of rulers. This can be seen from 946 onwards in the annual alternation of court days in Aachen and Quedlinburg at Easter.

Otto did not change his practice of appointing duchies as offices of the empire at his discretion after these elevations to the nobility, but combined them with dynastic politics. While Otto's father Heinrich had still relied on amicitia (bonding of friends) as an important instrument for stabilizing his kingship, marriage now took its place. Otto refused to accept uncrowned rulers as equal contractual partners. The integration of important vassals now took place through marriage connections: the West Frankish King Ludwig IV married Otto's sister Gerberga in 939 . Otto appointed the Salian Conrad the Red as duke in Lorraine in 944 and tied him more closely to the royal family in 947 by marrying his daughter Liudgard. He satisfied his brother Heinrich's claim to a share of power by marrying him off to Judith , daughter of Duke Arnulf of Bavaria, and installing him as duke in Bavaria in the winter of 947/948, after the duchy had been terminated with the death of Arnulf's brother Berthold had become free. The bestowal of the Bavarian dukedom on Otto's previously rebellious brother Heinrich marked his final renunciation of the kingship. The king's closest relatives assumed the most important positions in the empire, while Franconia and Saxony continued to report directly to the king without ducal authority.

Shortly after Edgith 's death on January 29, 946, who was buried in Magdeburg, Otto began to arrange his own successor. He had his son Liudolf 's marriage, which had already been negotiated in 939, to Ida , the daughter of Duke Hermann of Swabia, leader of the Konradines who had remained loyal to him, probably in the late autumn of 947 and declared him his successor as king. All the leaders of the empire were called upon to swear an oath of allegiance to his son, who had just come of age. In a binding form, Liudolf received the promise that he could become his father's successor. By doing so, he upgraded Hermann and secured his own house the succession in the duchy, as Hermann had no sons. As planned, Liudolf became Duke of Swabia in 950.

Relations with other rulers in Europe

Otto's politics of domination were embedded in the political context of early medieval Europe. His decision for Aachen as the place of coronation already raised the problem of relations with West Francia . Aachen was in the Duchy of Lorraine , claimed by the west Frankish kings, who were still Carolingians . However, the ruling family in West Francia was already severely weakened by the power of the high nobility. By presenting himself as the legitimate successor to Charlemagne, Otto saw his claim to Lorraine as legitimate. During Henry's uprising and later, in 940, the West Frankish King Louis IV tried to establish himself in Lorraine, but failed because of Otto's military strength and because Louis' domestic political rival Hugo the Great was married to Otto's sister Hadwig . Ludwig was still able to assert his claims to Lorraine by marrying Gerberga, the widow of the rebellious Duke Giselbert, who died in 939. Since this was another of Otto's sisters, he became a brother-in-law of both Otto and his own domestic political rival Hugo. So Otto pursued a similar marriage policy towards the West Frankish Empire as towards the dukes in East Franconia. In 942, Otto mediated a formal reconciliation: Hugh of France had to perform an act of submission, and Louis IV had to relinquish any claims to Lorraine.

In 946, the West Frankish kingdom fell into a crisis when King Ludwig was betrayed and first captured by a Danish king and then in the hands of his main opponent Hugo. Otto had already mediated the peace between Ludwig and Hugo in 942 and therefore had to watch over the existence of the peace, which had been severely disturbed by the capture. At the urgent pleas of his sister Gerberga, Otto intervened in the West on behalf of Ludwig. However, Otto's military power was insufficient to take fortified cities such as Laon , Reims , Paris or Rouen . After three months, Otto broke off the army without having defeated Hugo. But he managed to expel Archbishop Hugh of Reims from his episcopal city.

In 948, the Universal Synod of Ingelheim , in which 34 bishops took part, including all the German archbishops and the Reims candidate Artold , settled the years-long dispute between Ludwig and Hugo, which also involved the occupation of the Reims archchair . The choice of the conference venue in the East Frankish Empire shows that Otto saw himself as an arbiter in the West Frankish Empire. The assembly presented themselves to King Otto, and in the Reimser Schism they decided in favor of his candidate Artold against Hugo, Hugo von Franzien's favourite. Louis IV was excommunicated in September 948 . However, his position as a member of the family was gradually improved by Otto, first at Easter in the year 951, then two years later in Aachen, where the final reconciliation took place.

However, not only West Frankish problems were dealt with at the universal synod of Ingelheim. The bishops of Ripen , Schleswig and Aarhus were ordained . All three bishoprics were placed under Archbishop Adaldag of Hamburg - Bremen . These diocese foundations and the founding of other bishoprics in Brandenburg and Havelberg in the same year meant an intensified Christianization. Nationalist historiography interpreted these measures anachronistically as "Ostpolitik" aimed at expansion and subjugation of the Slavic territories . However, there are no signs of the Ottonian rulers asserting themselves against the Danes and Slavs. Unlike Charlemagne, Otto's commitment to the Slavs and heathen missions was limited in time and, despite some violent conflicts, was much more reserved. Otto appears to have been content with acknowledging suzerainty over the Slavic territories.

East Francia had good relations with the Kingdom of Burgundy ever since Henry I had acquired the Holy Lance from King Rudolf II . When Rudolf died in 937, Otto brought his underage son Konrad to his court in order to prevent Hugo of Italy from taking over Burgundy, who immediately married Rudolf's widow Berta and betrothed his son Lothar to his daughter Adelheid . After the death of the Italian King Hugo on April 10, 947, Otto also ensured that Lower Burgundy and Provence fell to his protégé Conrad, which further strengthened his relationship with the Burgundian royal family. Otto respected Burgundy's independence and never seized the Burgundian crown.

Close contacts also existed between Otto I and the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos (944-959). The contemporary sources tell of numerous embassies traveling from West to East and from East to West on political matters. On October 31, 945, and again on the occasion of Easter 949, "envoys of the Greeks brought our king twice gifts from their emperor, which both rulers honored," reports Thietmar von Merseburg in his chronicle. At that time, negotiations about a marriage alliance between Byzantium and the Ottonian ruler were unsuccessful.

Intervention in Italy and marriage to Adelheid of Burgundy

With the death of Berengar I of Italy, the western empire came to an end in 924. So every ruler of a Frankish sub-empire was free to adorn himself with imperial splendor without evoking unwelcome reactions. However, Otto's plan for the coronation of the emperor seems to have condensed into a fixed action concept only late. As long as Queen Edgith was alive, Otto's activities were primarily focused on the East Frankish kingdom.

In Italy, Hugo and Lothar's regiment aroused some resentment among the great, at the head of which was Berengar of Ivrea . However, in 941 he had to flee to the court of Otto, who thus came into direct contact with Italy's political problems for the first time. Otto, however, avoided a dedicated partisanship. He neither delivered his guest to Hugo nor gave him his express support when Berengar returned over the Alps of his own accord in 945 and quickly cornered Hugo in northern Italy. Hugo died in 948 in his home country of Provence, where he had escaped, and left the field to his son Lothar. Before a major argument broke out, Lothar died suddenly on November 22, 950 and widow Adelheid , who was not yet 20 years old.

According to Longobard tradition, Adelheid could pass on the royal dignity through marriage. For this reason, Berengar took them captive and declared himself king on December 15, 950, only three weeks after Lothar's death, with his younger son Adalbert as co-regent. But he was not universally recognized either, and the dissatisfied looked at Adelheid, who apparently had adopted the idea of being able to determine the future of the empire through a new marriage.

Adelheid was not only the widow of the Italian king, but also related through her mother Berta to the Swabian ducal family, of which Otto's son Liudolf had become the head through his marriage to Ida. Above all, Otto himself was very interested in intervening in Italy. Since he had been a widower himself since 946, he had the opportunity to marry Adelheid and thus extend his rule to Italy. In addition, this offered the prospect of imperial dignity. After Adelheid was arrested, Otto decided to move to Italy; whether he was asked to do so or even asked to take over the rule is unclear. Probably already in the spring of 951 Liudolf had ridden to Italy with only a few companions without any understanding with his father. What Liudolf intended with this is uncertain. In any case, his undertaking failed due to the intrigues of his uncle Heinrich , who had secretly warned Liudolf's opponents without being challenged by Otto.

Heinrich was even used by Otto as an army commander and was the most important intermediary on Otto's Italian campaign in September 951, which went without fighting. Heinrich led Adelheid from her refuge in Canossa to Pavia , where Otto married her in October. He took over the Italian royal dignity without an act of elevation being expressly mentioned in the sources. His chancery dubbed him on October 10, clearly referring to Charlemagne, "King of the Franks and Lombards" (rex Francorum et Langobardorum) and on October 15 as "King of the Franks and Italians" (rex Francorum et Italicorum) .

Uprising of Liudolf

The marriage to Adelheid created tensions between the king and his son and designated successor Liudolf , as the rights of the sons of the marriage arose. Liudolf also mistrusted the growing influence of his uncle, the former rebel Heinrich. Henry probably disagreed about who should occupy the position of secundus a rege (the second after the king): the brother or the son. In any case, Liudolf left his father in November in demonstrative displeasure and without saying goodbye, which was tantamount to an affront . He was accompanied across the Alps by Archbishop Frederick of Mainz . The archbishop had personally traveled to Rome on Otto's behalf to ask the pope about a coronation as an emperor, but his journey was in vain: Pope Agapet II rejected Otto's plans for reasons that are not known in detail. It may be due to the clumsiness of the ambassador.

At Christmas 951, Liudolf organized a feast (convivium) in Saalfeld , at which he gathered around him Archbishop Friedrich von Mainz and all the great people of the empire who were present. This revelry was already suspicious to many contemporaries and was reminiscent of the convivium that Henry had celebrated a good decade earlier to initiate an armed uprising against Otto. Bindings were activated with the feast to gather resistance against the king. In response, Otto returned to Saxony with Adelheid in February 952 and demonstratively refused his favor to the son . Otto celebrated the Easter Day in Saxony as probably the most important event of the year "to represent sovereign power and divine legitimacy".

Liudolf found a powerful ally in his brother-in-law, Conrad the Red . Through negotiations in Italy, Konrad had persuaded Berengar to visit Otto in Magdeburg, and Berengar had obviously made binding promises about the outcome of this meeting. A group of dukes, earls and courtiers, led by dukes Konrad and Liudolf, recognized Berengar as king and ostentatiously expressed this in a reception. Arrived at court, however, Otto initially kept Berengar waiting for three days in order to snub him, allowed none of Konrad's promises and only granted Berengar free departure. Because Duke Konrad and the other supporters of Berengar felt Otto's answer as a personal insult, they joined the opponents of the king.

Despite the resistance that developed in this way, a compromise was reached on the question of Berengar's position. At a court day in Augsburg, at the beginning of August 952, the opponents agreed on a place for the submission (deditio) of Berengar and for a voluntary alliance (foedus spontaneum) with Otto as a fief. However, the Verona and Aquileja brands were awarded to Duke Heinrich of Bavaria.

After Adelheid had given birth to a first son, Heinrich, in the winter of 952/953, Otto is said to have wanted him as his successor instead of Liudolf. In March 953 the uprising broke out in Mainz . When Otto wanted to celebrate Easter in Ingelheim , Konrad and Liudolf openly showed him the “signs of rebellion” (rebellionis signa) . Liudolf and Konrad had meanwhile brought together a large group of armed men - mainly young people from Franconia, Saxony and Bavaria are said to have been among them. The king was therefore unable to celebrate Easter as the most important act of representation of power, neither in Ingelheim nor in Mainz or Aachen . More and more noble groups allied themselves with Liudolf. When Otto heard that Mainz had fallen into the hands of his enemies, he moved there in great haste and began to lay siege to the city in the summer. Archbishop Frederick of Mainz had tried to mediate at the beginning of the uprising, but the king "ordered his son and son-in-law to hand over the perpetrators of the crime for punishment, otherwise he would consider them outlawed enemies (hostes publici) ". This demand was unacceptable to Liudolf and Konrad, since they would have had to betray their own allies. Such behavior would have made them perjurers, for it was customary to take oaths of mutual support before entering into a feud .

The center of the conflict shifted to Bavaria in 954. There, with the support of Arnulf , one of the sons of the Duke of Bavaria who died in 937 , Liudolf had conquered Regensburg , seized the treasures accumulated there and distributed them among his followers as booty. At Henry's urging, the king's army immediately made its way south to regain Regensburg, but the siege dragged on until Christmas. Simultaneously with the war actions, Otto made two important personnel decisions: Margrave Hermann Billung was made duke and king's deputy in Saxony, and Brun, the youngest of the king's brothers, was promoted to archbishop of Cologne . In order to end the conflict, negotiation was also chosen in Bavaria.

Lechfeld battle

When Liudolf rose up against Otto, the Hungarians were still threatening the empire. Although the Eastern Marches were established to protect against pagan Slavs and Magyars , the Hungarians remained a constant threat on the eastern frontier of the East Frankish Empire. The Hungarians knew the empire and its internal weakness, which gave them reason to invade Bavaria with a large force in the spring of 954. It is true that Liudolf and Konrad had managed to protect their own territories by giving the Hungarians westward leaders, who escorted them east of the Rhine through Franconia. In addition, Liudolf had organized a large banquet in Worms on Palm Sunday in the year 954 in honor of the Hungarians and showered them with gold and silver. But Liudolf was now accused of having made a pact with the enemies of God and suddenly lost supporters to Otto. Bishops Ulrich von Augsburg and Hartpert von Chur , who were the king's closest confidants, mediated a meeting between the conflicting parties on 16 June 954 at a court day in Langenzenn . It was not so much the causes of the conflict between father and son that were negotiated, but rather the reprehensibility of Liudolf's pact with the Hungarians. His defense that he "did not do this of his own free will, but was driven by external necessity" was not convincing.

As a result of these negotiations, Archbishop Frederick and Conrad the Red separated from Liudolf, who was not ready to submit, but continued to fight alone against his father, who was again besieging Regensburg. Twice the son personally came out of town to ask for peace from the father. Only the second time did he receive it through the mediation of the princes. The final settlement of the dispute was adjourned to a court day in Fritzlar . The conflict was settled by ritual deditio (submission). In the fall of 954, during the royal hunt in Suveldun near Weimar , he threw himself barefoot on the ground in front of his father and begged for mercy, which he was granted. "So he was restored to grace in fatherly love, and vowed to obey and to do in all things the will of the Father."

The Hungarians had meanwhile been held up in front of Augsburg, since Bishop Ulrich had the city tenaciously defended. In this way he gave Otto time to gather an army and rush to the relief of Augsburg. The Battle of Lechfeld on August 10, 955 permanently eliminated the Hungarian threat. The triumphant victory consolidated Otto's power and prestige. According to Widukind von Corvey , whose account is disputed, Otto is said to have been proclaimed imperator by the victorious army on the battlefield , and the court chancellery did not change Otto's title after 955 until February 962. According to the testimony of Thietmar von Merseburg , Otto vowed before the Battle of Lechfeld, in the event of victory, to the Saint Laurentius to establish a bishopric in his Merseburg Palatinate in his honor.

After the victory, Otto had thanksgiving services celebrated in all the churches of the empire and attributed the victory to the help of God, which made the divine right of the ruler visible. From 955 at the latest, he also drew up concrete plans for the establishment of an archbishopric in Magdeburg. The church in which Queen Edgith was buried in 946 was followed by a stately new building in 955, decorated with marble and gold, according to Thietmar. In the summer of 955 he sent Abbot Hademar from Fulda to Rome, where he obtained permission from Agapet II for the king to establish bishoprics as he pleased. A protest letter from Mainz Archbishop Wilhelm to Pope Agapet II in 955 reveals that Otto evidently intended to relocate the Halberstadt diocese in order to create the new Magdeburg archdiocese within its borders. According to Wilhelm, the plan was to transfer the diocese of Halberstadt to Magdeburg and raise it to the status of an archbishopric. It would thus have left the association of the Archdiocese of Mainz . However, such far-reaching changes required the consent of the bishops concerned. Wilhelm and Bishop Bernhard of Halberstadt vehemently refused to agree to such a diminution of their diocese. Otto therefore initially refrained from proceeding further in this matter. Resistance to Otto's Magdeburg plans must have been considerably stronger in Saxony, for Widukind of Corvey, Hrotsvit of Gandersheim , Ruotger of Cologne , Liudprand of Cremona and the continuator Reginonis, who later became Archbishop Adalbert of Magdeburg , reported on the founding of Magdeburg with no one Word.

The Lechfeld Battle is considered a turning point in the king's reign. After 955, in the East Franconian-German Empire, until Otto's death, there were no more uprisings by the nobles against the king, as had flared up repeatedly in the first half of his reign. Furthermore, Otto's dominion was spared from the incursions of the Hungarians. They settled down after 955 and soon embraced Christianity.

In the same year, Slavic Abodrites invaded Saxony. In response, King Otto moved east with an army after defeating the Hungarians. When the Abodrites refused to pay tribute and submit, they suffered another military defeat at the Battle of the Recknitz . In contrast to their leniency towards internal rebels, the Ottonians were ruthless and cruel towards external enemies. After the battle, the leader Stoinef was beheaded and 700 prisoners killed. With the end of the fighting in the autumn of 955, the turbulent period around the uprising of Liudolf ended.

Ottonian Imperial Church

Not only did his son's uprising temporarily weaken Otto's rule, but important players also died within a very short time, such as Otto's brother Heinrich of Bavaria in 955. Conrad the Red, who was no longer a duke, but was still one of the most important people in the East Frankish kingdom was, fell in the battle on the Lechfeld. Liudolf was sent to Italy at the end of 956 to fight Berengar there, but he succumbed to a fever on September 6, 957 and was buried in St. Alban Abbey near Mainz .

The Duchy of Bavaria, which had been vacated by Henry's death, was not reassigned but was left under the regency of Henry's widow Judith for their four-year-old son Henry . Only Swabia received a full-fledged new duke, Adelheid's uncle Burkhard , who became more closely tied to the ruling family by marrying Judith and Heinrich's daughter Hadwig . As a result, shortly after his triumph over the uprising, Otto suddenly broke away from important structures in the empire. In addition, the first two sons of his second marriage died young and the third son Otto was not born until the end of 955.

According to older research, Otto made a second attempt after the Battle of Lechfeld to consolidate the empire by using the imperial church for his purposes against the worldly greats. Otto's younger brother Brun in particular, who had been chancellor since 940 , archchaplain of the empire since 951 and archbishop of Cologne since 953 , is said to have prepared clerics in the court chapel for their future work as imperial bishops. Recent research has been more cautious in assessing this so-called Ottonian-Salian imperial church system. With Poppo I of Würzburg and Othwin of Hildesheim , only two of the 23 bishops invested by Otto from the Mainz ecclesiastical province came from the court chapel. Rather, the cathedral chapter in Hildesheim and the cathedral schools played a central role in the relationship between king and bishop. The king could by no means alone decide on the filling of episcopal offices. Especially in the second phase of his government, an increase in intercessions in bishopric elections was observed. Sons from noble families were given preference in the court orchestra. As ecclesiastical dignitaries, they were protected by canon law and largely removed from royal influence.

The imperial church received numerous donations, which, in addition to land ownership, also included royal sovereign rights (regalia) such as customs, coinage and market rights. These donations, however, obligated the recipients to serve the king and the empire. The Ottonian kings allowed themselves to be housed and boarded by the imperial churches. It was also the imperial churches that already at the time of his son and successor Otto II provided two-thirds of the cavalry army in times of war, but were also obliged to pay tribute in kind ( servitium regis ) in times of peace . In addition to the supply function, the imperial monasteries and bishoprics served to implement the religious order willed by God, to provide prayer support and to increase Christian worship.

Preparation of the second train to Italy

A serious illness of Otto in the year 958 contributed to the serious crisis of the empire in addition to the uprising of Liudolf. Berengar II used it to further consolidate his power, although formally he only held Italy as a fief of Otto. Liudolf's death and Otto's problems in the northern part of the empire in view of numerous vacant duchies seem to have encouraged Berengar to bring Rome and the patrimony of Peter under his influence after northern Italy . He came into conflict with Pope John XII. , who asked Otto for help in the autumn of 960. Several great Italians also intervened at Otto's court with a similar aim, including the Archbishop of Milan , the Bishops of Como and Novara and the Margrave Otbert. The path to the imperial coronation has been treated differently in research. There is controversy over whether Otto's policy was aimed at a long-term renewal of the Carolingian empire or whether it was solely the initiative of the pope in an acute emergency.

The king, who had since recovered, carefully prepared his march to Rome. At the Hoftag in Worms in May 961, he had his underage son Otto II elevated to the position of co-king. At Pentecost 961, Otto II was worshiped by the Lorraines in Aachen and anointed king by the Rhenish Archbishops Brun of Cologne, Wilhelm of Mainz and Heinrich of Trier . The long absence brought with it numerous "problems of realizing power". The trains to Italy required high performance from the noble families and the imperial churches. Rule was essentially dependent on the presence of the king. A stable network of relatives, friends and followers had to guarantee the maintenance of order during the ruler's absence. The two archbishops Brun and Wilhelm were appointed deputies of the empire. The young Otto II stayed with them north of the Alps. During Otto's absence in Italy, the king's son wrote independently north of the Alps. Through compensation, such as priority over other bishops and the right of the king to be crowned, Otto broke Wilhelm's resistance and from then on received his support for his Magdeburg plans.

Imperial coronation and Italian politics

In August 961, Otto's army set out from Augsburg for Italy, crossing the Brenner Pass to Trento . The first destination was Pavia , where Otto was celebrating Christmas. Berengar and his followers retreated into castles and avoided open battle. Without being stopped, Otto moved on to Rome.

On January 31, 962, the army reached Rome. On February 2, Pope John XII. crowned emperor. With the imperial coronation, a tradition was established for all future imperial coronations of the Middle Ages. Adelheid was also anointed and crowned and thus received the same rank. This was a novelty: not a single Carolingian wife had ever been crowned empress. For the couple, being crowned together meant claiming Italy as their possession, for themselves and for their heir, who had already been made king.

Fundamental changes occurred in the 960s in the image of the seal, in the perception of the ruler in historiographical representation and in the area of chancellery language. In February 962, the depiction of the ruler on the seals suddenly changed from Franconian-Carolingian models to a Byzantine model. According to Hagen Keller , these changes in the representation of rulers under Otto I can in no way be deduced as a result of the imperial crown, but the assumption of royal rule in Italy must have provided decisive impetus.

A synod on February 12 documented the cooperation between the emperor and the pope. To ensure the success of the mission, the pope decreed that the Moritz monastery in Magdeburg be made an archbishopric and the Laurentius monastery in Merseburg a bishopric. Otto and his successors were also given permission to set up more dioceses. The Pope obliged the archbishops of Mainz, Trier and Cologne to support these projects. In the document, John once again emphasized Otto's merits that justified his elevation to the throne: the victory over the Hungarians, but also the efforts to convert the Slavs. A day later, Otto exhibited the so-called Ottonianum . He thus recognized the papal property rights and claims, with which his Carolingian predecessors had already confirmed the possessions of the Roman Church to the incumbent pope. But the Privilegium Ottonianum went well beyond the preliminary documents in the awards and granted the papacy areas that previously belonged to the Kingdom of Italy. The possession of the city and ducat of Rome, the exarchate of Ravenna , the duchies of Spoleto and Benevento and a wealth of other possessions were recognized. However, none of the emperors actually relinquished the territories, and their possession remained a point of contention in papal-imperial relations until the Staufer period . The election of the Pope was also regulated by the Ottonianum; it should be the responsibility of the clergy and "people of Rome". However, the Pope could only be consecrated after taking an oath of allegiance to the Emperor. In addition, the Magdeburg plans were negotiated. Otto obtained from Pope John XII. a first founding document, according to which the Moritz monastery in Magdeburg should be converted into an archbishopric. But again the plan failed due to the opposition of the bishops of Mainz and Halberstadt. After the imperial coronation, Otto went back to Pavia, from where he led the campaign against Berengar , who withdrew in 963 to the impregnable castle of San Leo near San Marino .

Apparently upset about Otto's will to power, John XII. in the spring of 963 an unexpected reversal. He received Berengar's son Adalbert in Rome and formed an alliance with him against the emperor. As a result, in October 963, Otto had to break the summer-long siege of Berengar and rush to Rome to reassert his claim. However, there was no fight and Johannes and Adalbert fled. Immediately upon his entry, Otto had the Romans swear an oath that he would never elect or consecrate a pope before they had obtained the approval or vote of the emperor and his co-king.

In Rome, a synod sat in the presence of the emperor to judge the pope. Pope John XII replied by letter threatening to ban all who dared depose him. As a reaction, the synod actually had John deposed and made Leo VIII the new pope, which no emperor had ever dared to do before, since according to the papal self-image only God was allowed to judge the successor of the apostle Peter. At the same time, Berengar and his wife Willa were captured and exiled to Bamberg . Thus, by the end of 963, a return to more stable conditions in Italy and Rome seemed to have been achieved. But the deposed pope managed to unleash a rebellion by the Romans against Otto and Leo VIII, which the emperor was initially able to control. However, after his departure from Rome, the Romans took John XII. back in the city, and Leo had no choice but to flee to the emperor. A synod declared the decisions of the previous imperial synod invalid and Leo VIII deposed. Even before an armed conflict could break out, John XII died unexpectedly on May 14, 964, and the Romans elected a new pope , Benedict V , in defiance of the imperial ban. Otto then besieged Rome in June 964 and was able to move into the city after a few weeks. There he enthroned Leo VIII again and had Benedict sent into exile in Hamburg .

Rome and Magdeburg: The Last Years

After the preliminary arrangement of the situation, Otto returned to the northern part of the empire in the winter of 965. His procession was accompanied by several large court festivals. Since writing became less important as an instrument of power in the 10th century compared to the Carolingian period , ritual acts of representation of power gained in importance. The court festivities thus became the most important instrument for the realization of power. In order to give expression to the hope for dynastic continuity, the anniversary of the imperial coronation was celebrated on February 2nd in Worms , the site of Otto II's election as king. A few weeks later, Otto celebrated Easter in Ingelheim . A big court day in Cologne at the beginning of June, at which almost all members of the imperial family were present, was the highlight.

But the calm in Italy was deceptive. Adalbert, the son of Berengar, fought again for the royal crown of Italy, so that Otto had to send Duke Burkhard of Swabia against him, who successfully completed his task.

Otto was now able to continue to realize his plans to found the Archdiocese of Magdeburg and made a far-reaching decision at the end of June. After the death of Margrave Gero , who had borne the brunt of the fighting on the Slavic border since 937, the emperor decided to split the margraviate into six new dominions. The three southern ones roughly coincided with the districts of the later bishoprics of Merseburg , Zeitz and Meissen . However, Brun's death on October 11, 965 deprived Otto of a person who had always seen himself as a loyal assistant to her royal brother from the very beginning in the court orchestra.

On October 1st, Pope John XIII. elected successor to the late Leo VIII with the approval of the Ottonian court. But just ten weeks later he was captured by the city Romans and imprisoned in Campania . His cry for help prompted Otto to move back to Italy. He would spend the next six years there.

In August 966 in Worms, Otto arranged for representation during his absence: Archbishop Wilhelm was to be responsible for the empire, Duke Hermann for Saxony. Then he moved to Italy with an army force via Chur . The repatriation of the Pope on November 14, 966 went without resistance. The twelve leaders of the Roman militia who had captured and mistreated the pope were punished by the emperor and pope with death on the cross. In 967 Emperor and Pope John XIII. to Ravenna and celebrated Easter there. At a subsequent synod, the Magdeburg question was negotiated again. In contrast to the preliminary document of 962, the scope of the planned ecclesiastical province was defined in more detail in a papal document. Magdeburg was to be elevated to the status of an archbishopric and the dioceses of Brandenburg and Havelberg from the Mainz diocese were to be assigned to it, and new dioceses were to be established in Merseburg, Meißen and Zeitz. However, the realization of the new diocese organization still required the consent of the bishop of Halberstadt and the metropolitan of Mainz . Bernhard von Hadmersleben (923 to 968), the bishop of Halberstadt, refused to consent to the establishment of the Magdeburg ecclesiastical province until the end of his life.

After Bishop Bernhard von Hadmersleben, Archbishop Wilhelm von Mainz and Queen Mathilde died in the first months of 968 , Otto's plans for founding Magdeburg continued to take shape. The emperor could oblige the successors of the deceased bishops to agree to his plans before the investiture . He ordered the bishops Hatto von Mainz and Hildeward von Halberstadt to visit him in Italy and obtained from the Bishop of Halberstadt that parts of his diocese be ceded to Magdeburg and others to Merseburg. Archbishop Hatto also gave his consent to the subordination of his dioceses of Brandenburg and Havelberg to the new Archdiocese of Magdeburg. However, in a letter from an unknown sender, Otto was dissuaded from his candidate, the abbot of the Moritz monastery Richar, and he agreed to the demand to appoint the Russian missionary and abbot of Weißenburg , Adalbert , as the new archbishop of Magdeburg. The new Archdiocese of Magdeburg served above all to spread the Christian faith and was the intended burial place for Otto from the start. Due to the difficult Italian conditions, however, Otto was not able to personally witness the establishment of the archdiocese. It was only in the spring of 973, four and a half years after it was founded, that Otto first visited the Archdiocese of Magdeburg.

Parallel to the Magdeburg plans, from February 967 Otto shifted his radius of action to the area south of Rome. On trains to Benevento and Capua he accepted homage from the dukes there. Since Byzantium claimed supremacy over these areas and its rulers saw themselves as the only legitimate holders of the imperial title, the conflicts with Emperor Nikephoros Phocas intensified, who resented Otto's contact with Pandulf I of Capua and Benevento . Nevertheless, the Byzantine seems at first to have been willing to enter into peace and friendship, which was also important to Otto, who also thought of a purple-born Byzantine princess as a bride for his son and successor. Otto obviously expected legitimation and splendor for his son and his family from his marriage to the glorious Macedonian dynasty . In order to promote his dynastic plans, Otto, in a letter written together with the Pope, asked his son to travel to Rome in the autumn of 967 to celebrate Christmas with them.

The elevation of the young Otto was probably decided with the invitation. His father traveled to Verona to meet him . Three miles from the city, Otto and his son were solemnly overtaken by the Romans on December 21, and on Christmas Day John XIII. Otto II as co-emperor. The aspired marriage was intended as a catalyst to clarify the open questions: the problem of the two emperors and the regulation of the sphere of rule in Italy within the framework of a friendly alliance in which neither party had to accept a loss of prestige. As a result, military involvement in southern Italy played out in parallel to legation traffic in the next few years. In order to regulate the situation in southern Italy and to expand, in 969 the emperor and pope elevated the diocese of Benevento to an archbishopric. It was only when Nikephoros was murdered and replaced by Johannes Tzimiskes in December 969 that the new Byzantine emperor accepted the Ottonians' courtship and sent his niece Theophanu , a princess who was not born " purple " but still came from the imperial family, to Rome. In the year 972, immediately after the marriage, Theophanu was crowned empress by the pope on April 14th. Otto II, as co-emperor, assigned large estates to his wife with a ceremonial certificate . The marriage of Otto II with Theophanu eased the conflicts in the southern parts of Italy; However, it is not known how the reorganization of the conditions there was actually carried out. After the wedding celebrations, it was only a few months before the imperial family returned to the empire in August.

After his return to the East Frankish Empire, a synod was held in Ingelheim in September 972 . This mainly dealt with the succession plan for Bishop Ulrich von Augsburg . Otto and Ulrich had already agreed on Ulrich's nephew Adalberto in Italy . However, the synod initially decided against the designated candidate, since Ulrich's nephew already openly carried the bishop's crosier. The crisis was resolved by an oath by which Adalberto had to confirm that he had unwittingly become a heretic. This decision clearly belied the approval that Otto the Great had given to the plan and illustrated the self-confidence of the Ottonian episcopacy. In the spring of 973, the Emperor visited Saxony and celebrated Palm Sunday in Magdeburg. At the same time, this celebration in Magdeburg restored an order that had been provocatively questioned the previous year. Otto's deputy in Saxony, Hermann Billung, who had been loyal until then, had allowed Archbishop Adalbert to take him to the city like a king. In Otto's Palatinate he had taken his place at the table and even slept in the king's bed and finally made sure that this was reported to the emperor. Apparently, the usurpation of the royal reception ceremony was a protest against the emperor's long absence. Otto had stayed in Italy for six years without interruption, so that the authority of the king in his homeland began to decline in a ruling association that was primarily structured by personal staff.

The Easter festival on March 23, 973 in Quedlinburg showed the emperor at the height of his power and the European dimension of his rule. In Quedlinburg he received ambassadors from Denmark, Poland and Hungary, but also from Byzantium, southern Italy and Rome, even from Spain. For the prayer days and Ascension Day , Otto came to the Palatinate Memleben via Merseburg . Here he became seriously ill. After bouts of fever, he asked for the last sacraments and died on May 7, 973 in the same place where his father had died.

The transfer of power to his son Otto II was seamless, since the succession had already been settled by the coronation of Otto II. The next day, the elders who were present confirmed the son, who was now the sole ruler, in his office. After a magnificent 30-day funeral procession in the presence of Archbishops Adalbert of Magdeburg and Gero of Cologne , his father was buried in Magdeburg Cathedral alongside his wife Edgith, who died in 946.

effect

Continuity and change under Otto II.

In Italy, the unresolved problems of his father's last decade persisted, that is, above all, domination of Italy and responsibility for the papacy. Otto II broke with his father's tradition in his policy towards Italy . In relation to Venice , which had always successfully defended itself against territorial integration into the empire and political subordination, the new emperor took massive action - regardless of the long-standing, amicable relations between Venice and the Rich.

While the first trade blockade ordered by Otto II in January or February 981 hardly affected Venice (cf. Economic History of the Republic of Venice ), the second in July 983 caused considerable damage to Venice and split its ruling group. Only the early death of Otto II possibly prevented the threatening submission of Venice to the Empire.

Otto I had limited himself to binding the principalities of Capua , Benevento and Salerno to himself under feudal law; his son pursued much more far-reaching goals. Otto II made great efforts to subject them to his imperial rule more intensively and directly, both politically and ecclesiastically.

Otto II also broke new ground in the religious and monastic areas: monasticism and monasteries were to serve as power-supporting and stabilizing factors in the imperial structure. While Otto the Great founded only one monastery with St. Mauritius in Magdeburg in 37 years of reign, Otto II may claim the rank of founder or co-founder for at least four monasteries - Memleben , Tegernsee , Bergen near Neuburg /Donau and Arneburg . The active involvement of monasticism in imperial politics was a fundamental constant in his relationship to the monastic system, whose representatives he entrusted with central political functions.

The plan to set up an ecclesiastical province did not come to an end with the founding of the Archdiocese of Magdeburg after 968. Otto had to leave it to his successor and his assistants to regulate many of the details, starting with the exact demarcation of borders through to furnishing the new dioceses. In 981, Otto II used the first opportunity to abolish the diocese of Merseburg by placing its bishop Giselher on the Magdeburg throne. This step seems to have been planned for the long term and agreed with the most important bishops. It is not known what was the decisive factor in turning away from Otto the Great's work.

A year after the suppression of Merseburg, the imperial army was crushed at Crotone by Muslim Kalbite troops in southern Italy. Another year later, the Slavic tribes across the Elbe successfully rose up against Ottonian rule. Finally the emperor died in 983 at the age of 28 and left behind a son who was only three years old .

Cultural boom

The collapse of the Greater Franconian Empire had led to a decline in cultural life. It was only after Heinrich I introduced the new rulership and Otto finally secured it with the Hungarian victory in 955 that it was able to flourish again. This cultural boom can be divided into two phases. During the first phase, the royal court secured the material conditions and thus created the basis for advancement. Otto's success in power brought new sources of income, such as tributes from the Slavic region in the east and the newly opened silver veins in the Harz Mountains. These also benefited the churches.

The second phase was determined by the work of Otto's spiritual brother Brun . As head of the court chapel and archbishop of Cologne, Brun made a special effort to promote the cathedral schools, but also art and church building. Cathedral schools were built in Magdeburg, Würzburg and in numerous other places based on his example. In addition, monasteries such as Fulda , St. Gallen , St. Emmeram / Regensburg or Corvey retained their place as centers of education. Ultimately, it was the women's foundations sponsored by Otto that heralded the so-called Ottonian Renaissance . The most important works of the time were created in the diocese and monasteries that were most closely associated with the king. Widukind von Corvey and Hrotsvith von Gandersheim proudly confessed that the king and his successes had inspired them to their works.

Bishops such as Gero von Köln or Willigis von Mainz competed in church building and hired illuminators, goldsmiths or bronze casters to make the liturgy of their churches ever more magnificent. Ottonian art, which developed as a result of exchange and competition between different centres, fell back on late antique and Carolingian traditions and incorporated contemporary Byzantine suggestions, without being able to precisely define the share of the various influences in each case.

Judgments of medieval historiography

In the 10th century, the importance of writing as an instrument of ruling practice and communication declined enormously compared to the High Carolingian period. Only since the middle of the 10th century, with the works of Widukind , Liudprand , Hrotsvit , the Mathildenviten and Thietmar 's chronicle, did a whole series of historical works come into being, which were primarily dedicated to the Ottonian ruling family. The authors legitimized Otto's kingship with three strategies: the express will of God (divine electio ), the recognition of Otto by the ecclesiastical and secular principes (princes), and the strengthening of the dynastic principle.

The Ottonian historian Widukind von Corvey is regarded as the "key witness" for the history of Otto I. With the Res gestae Saxonicae he wrote a "history of the Saxons" that goes back to their legendary conquest in the 6th century and Otto as a climax that surpasses everything that came before in the history of the Saxons. For Widukind, Otto was even “the head of the whole world” ( totius orbis caput ). He dedicated his historical work to Otto's daughter Mathilde . It must therefore have been clear to him that the content of his work would become known to the ruler. He repeatedly emphasized that " devotio " (devotion) guided him in writing, and he asked for " pietas " (loyalty) of the high readers in the reception of his work. For example, Widukind began his report on Friedrich von Mainz , who had become rebellious against Otto, with the imploring assurance: “It is not my place to disclose the reason for the defection and to reveal the royal secrets ( regalia mysteria ) . But I think I have to suffice for the story. If I am guilty of something, may I be forgiven.” Such topoi of modesty are, however, often found in historiography.

Widukind unveiled a surprising legitimation strategy by ignoring the imperial coronation and developing a “Roman-free imperial idea”, so to speak. Instead of being sacralized by the pope and crowned by the emperor, the emperor was acclamated by the victorious armies. Otto's victory on the Lechfeld became the actual act of legitimation of power. In addition to this idea of the imperial coronation in the style of ancient soldier emperors , Widukind also mixed Germanic and Christian ideas of rulership and heroism. The emperor is not a universal ruler, but a Germanic rex gentium , a supreme king over the peoples. Finally, the historian praises the achievements of Otto I's long reign: "The emperor ruled with fatherly grace, freed his subjects from their enemies, conquered the Avars, the Saracens, Danes and Slavs, conquered Italy, destroyed the idols of the pagan neighbors as well as churches and spiritual communities.”

Liudprand of Cremona was initially in the service of Berengar of Ivrea. After a quarrel with him, he found refuge with Otto and was appointed bishop of Cremona by him in 961 . In his main work Antapodose (retribution) Liudprand wanted to depict the deeds of all the rulers of Europe. The title Vengeance also points to a personal reckoning with King Berengar, whom Liudprand seeks to brand as a tyrant . For Liudprand, Otto's kingship is divine (divine electio) . Henry I was said to have been a humble ruler who overcame his illness and defeated the Hungarians (933). Otto I is his worthy successor, who also overcomes his enemies with God's help. Liudprand knew the Byzantine court from several legations. His ironic portrayal of Byzantine court life served Otto's greater fame, as a counter-image to glorify his reign.

For the historian Thietmar von Merseburg, the service provided for Merseburg was an essential criterion for assessing the Ottonian rulers. About forty years after Otto's death, Thietmar described his reign with the words: "The golden age shone in his days!" ( Temporibis suis aureum illuxit seculum ) He celebrated Otto as the most important ruler since Charlemagne.

A characteristic feature of all three depictions is that they show Otto as God's tool, as a king who gains his strength from walking on the right path and can therefore count on God's protection and help. In the historical works that were written at the end of his life or shortly thereafter, Otto the Great is mostly stylized as a hero. The works extol his successes, praise his administration and certify in many ways that he possessed all the qualities a king should have. However, there is also an anonymous historian from the Ottonian era who not only criticizes Otto, but also sees his life ended by divine revenge. This depiction comes from Halberstadt , where Otto was not forgiven for significantly reducing the size of the Halberstadt diocese in favor of founding the Archdiocese of Magdeburg and the Diocese of Merseburg.

The nickname "the Great" has been a fixed name attribute since the middle of the 12th century at the latest through Otto von Freising 's world chronicle. Otto von Freising found: Otto had brought the empire back from the Lombards to the "German East Franks" ( ad Teutonicos orientales Francos ) and was perhaps therefore named as the first king of the Germans (rex Teutonicorum) , although the empire had remained the Frankish one, in which only the ruling dynasty changed.

In the late 13th century, the Dominican chronicler Martin von Troppau called Otto the Great the first Emperor of the Germans ( primus imperator Theutonicorum ) .

Historical images and research perspectives

From the 19th century onwards, the Ottonian period became the focus of national history. In the Middle Ages, historians looked for the reasons for the late formation of a nation. The empire of Heinrich I and Otto I was considered the first independent German state. Through his victory in the Battle of Lechfeld in 955 against the Hungarians, the conquest of Italy and in 962 through the acquisition of the imperial crown, Otto gave Germany first place among the European peoples. With the founding of the Archdiocese in Magdeburg, Otto also initiated the Eastern Movement. For decades, Heinrich and Otto were regarded as the founders of the German Empire in the image of the Germans in the Middle Ages. Only through the research of the last decades on nation building such ideas, which were formerly regarded as certain, have been lost. Modern medieval studies see the German Empire as a process that was not yet complete in the 11th and 12th centuries.

From the point of view of national interests, the Sybel-Ficker dispute of the 19th century played off Italy policy against Ostpolitik, which is said to have been disastrous due to the fixation on Italy. Historical Ostpolitik came into focus when attempts were made to use historical arguments to decide the national configuration of Germany, the so-called Greater German or Lesser German solution .

The controversy over German imperial policy in the Middle Ages was triggered in 1859 by Wilhelm Giesebrecht . He glorified the imperial era as a “period in which our people, strong through unity, thrived to their highest development of power, where they not only freely ruled their own destiny, but also commanded other peoples, where the German man was considered the most in the world and the German name had the fullest sound.” The Prussian historian Heinrich von Sybel vigorously contradicted Giesebrecht. For Sybel, Otto was "no savior of Germany and Europe from the desolate misery of a time without an emperor". However, the German Empire and the German monarchy “did not benefit from the imperial splendor that had been achieved in this way.” His core demand was to see expansion in the East as the natural goal of the German people. According to Sybel, Charlemagne , Otto the Great, and even the red- bearded Friedrich would not have encouraged them, but recklessly jeopardized them and thus squandered the imperial power. Giesebrecht countered in 1861 that his political world view and his view of the past differed from that of Sybel only in the cardinal point. He also counted the development of power and world-dominating influence among his standards.

In 1861 Julius Ficker intervened in the historians' dispute and accused Sybel of taking anachronistic positions: there was no German nation in Otto's time; It was not the empire that was to blame for the decline, but rather Barbarossa's excessive reaching out to Sicily. Leopold von Ranke stayed away from the dispute. He interpreted Otto's empire more from the contrast between the Roman and Germanic worlds than from Italy or Eastern politics, with the former being represented by the church and the latter by the emperor from Saxony. As a result, new research approaches and questions such as Karl Lamprecht's cultural history were ignored. The dispute, in which the positions alternated between Small and Large German, Prussian and Austrian, Protestant and Catholic, also opened up European perspectives.

In 1876, in his most detailed description of Otto's government to date, Ernst Dümmler saw a "vigorous youthful upswing", a "national trend" under this emperor "go through the hearts of the people", "which at that time first began ... to call themselves German and German to feel". The historians' dispute divided historical science and shaped the judgments of historians in the early 20th century. Although Heinrich Class was "joyfully proud" of Otto's achievement in 1926, he nevertheless condemned his Italian policy as "disastrous and unfortunate". In 1936, Robert Holtzmann dedicated his biography of Otto to "the German people" with the remark that Otto "showed the way and goal of German medieval history, not only initiated the German imperial era, but truly dominated it for centuries to come".

Under National Socialism , under Heinrich I , “the national gathering of the Germans” began for the ideologues , under Otto the Great, “the conscious attempt at national formation and cultivation”. This tenor was soon spread by all of the party's training centers, including the " Völkischer Beobachter ". On the other hand, Heinrich Himmler and Prussian-oriented historians such as Franz Lüdtke or Alfred Thoss initially only wanted to see Otto's father Heinrich I as the founder of the German people. That changed with the “Annexation” of Austria and the “ Greater German ” claim to the Reich that came with it. At Himmler's invitation, Albert Brackmann , as the most influential and highest-ranking historian at the time, wrote the essay "Krisis und Aufbau in Ostend" immediately after the beginning of the war. A world-historical picture”, which was published by the SS-owned Ahnenerbe publishing house in 1939 and of which 7,000 copies were also ordered by the Wehrmacht for training purposes. Otto's plan to "subordinate the entire Slavic world" to the Archdiocese of Magdeburg is described as "the most comprehensive plan that a German statesman has ever made with regard to the East".

Adolf Hitler agreed with Sybel's assessment with a more favorable view of Otto. In Mein Kampf he named three essential and lasting phenomena that emerged from the “sea of blood” of German history: the conquest of the Ostmark after the Battle of Lechfeld, the conquest of the area east of the Elbe and the creation of the Brandenburg-Prussian state. Consequently, he named the first document of his activity as the new supreme commander of the Wehrmacht, "The military instruction for the invasion of Austria of March 11, 1938", " Operation Otto ", which ended with the instruction for renaming Austria to "Ostmark" of May 24, 1938 was completed. Hitler's new chief of staff, Franz Halder , who was not involved in "Operation Otto", worked out the campaign against Russia in 1940 as " Plan Otto ". To avoid duplication, it became “ Operation Barbarossa ”.

As late as 1962, on the occasion of the millennium of Leo Santifaller 's coronation , it was said that Otto had "a firm conception of a strong German state as a whole", that he had succeeded "in uniting the Reich internally and successfully fending off enemy attacks externally, that To expand the empire and extend the German sphere of influence almost all over Europe - so much so that Otto I's empire can be described as an ... attempt at European unification".