Fritzlar

| coat of arms | Germany map | |

|---|---|---|

|

Coordinates: 51 ° 8 ' N , 9 ° 16' E |

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Hesse | |

| Administrative region : | kassel | |

| County : | Schwalm-Eder district | |

| Height : | 220 m above sea level NHN | |

| Area : | 88.78 km 2 | |

| Residents: | 14,733 (Dec. 31, 2019) | |

| Population density : | 166 inhabitants per km 2 | |

| Postal code : | 34560 | |

| Primaries : | 05622, 05683 | |

| License plate : | HR, FZ, MEG, ZIG | |

| Community key : | 06 6 34 005 | |

| LOCODE : | DE FRZ | |

| City structure: | 11 districts | |

City administration address : |

Between the Krämen 7 34560 Fritzlar |

|

| Website : | ||

| Mayor : | Hartmut Spogat ( CDU ) | |

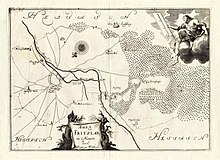

| Location of the city of Fritzlar in the Schwalm-Eder district | ||

Fritzlar is a small town and a medium- sized economic center in the Schwalm-Eder district in northern Hesse . The origin of the city goes back to a church and monastery founded by Bonifatius . The Cathedral - and imperial city is considered the place where both the Christianization of Central and Northern Germany (with the cases of Donareiche to 723 by Boniface) and the medieval German Reich (with the election of Henry I the king of the Germans on the Reichstag of 919) began. The name Fritzlar is derived from the original name Friedeslar , "Place of Peace".

geography

Geographical location

Fritzlar is located in the north Hessian highlands about 25 km (as the crow flies ) southwest of Kassel , on the southern edge of the " Fritzlarer Börde " ( natural area number 343.23) and north above the " Fritzlarer Ederflur " (natural area no. 343.211), on the north bank of the Eder .

The immediate vicinity of the city is characterized by fertile farmland and numerous, mostly wooded basalt knolls, many of which are “crowned” with medieval castles or their ruins; These include the Büraburg near Fritzlar, the Obernburg and the Wenigenburg in Gudensberg , the Hohenburg in Homberg , the Felsburg , the Heilgenburg and the Altenburg in or near Felsberg , the Jesberg Castle in Jesberg , the Falkenberg ruins near Wabern and the castle ruins Löwenstein in Oberurff-Schiffelborn .

Neighboring communities

Fritzlar borders in the north on the city of Naumburg , the municipality Bad Emstal (both in the district of Kassel ) and the city Niedenstein , in the east on the cities of Gudensberg and Felsberg , in the south on the municipality Wabern and the city of Borken , in the southwest on the municipality Bad Zwesten (all in the Schwalm-Eder district ), and in the west to the city of Bad Wildungen and the municipality of Edertal (both in the Waldeck-Frankenberg district ).

Districts

In addition to the core city of Fritzlar itself, there are ten districts:

These districts were incorporated during the municipal reform in Hesse in 1972 and 1974. Unthanken and Rothelmshausen were historically closely connected to Fritzlar, because they had been part of the Kurmainz ischen enclave Fritzlar since the 14th century . Until it was incorporated into Fritzlar, Züschen was an independent town in the Waldeck district and in the former principality of Waldeck . The other villages were historically Hessian.

Population development

In the Middle Ages, the city's population consistently ranged from 2000 to 3000 people. More detailed information is only available from 1740. In the 20th century there were three major leaps in the city's population: once after 1933 with the stationing of Wehrmacht troops in the city and the construction of the air base, a second time from 1956 with the establishment of a rather extensive Bundeswehr garrison in the city each time family members and civilian employees were involved, and a third time with the incorporation of nine surrounding villages on January 1, 1972 and the former Waldeck town of Züschen on January 1, 1974 with a total of more than 5500 additional residents.

|

|

|

Cityscape

Fritzlar's special features include the well-preserved medieval townscape with numerous half-timbered houses including the largely intact 2.7 km long town wall that surrounds the medieval town center.

The starting point and center of urban development was the predecessor of the monastery and collegiate church of St. Peter, erected in the 8th century, whose current building, the Fritzlar Cathedral , was built in two Romanesque construction phases from the late 11th to the early 13th century and dominates the cityscape. The Gothic church of the former Franciscan monastery is now a Protestant parish church, while the remaining and modernized buildings of this monastery are now part of the “Hospital of the Holy Spirit”.

The town hall is the oldest officially mentioned (1109) and still used as such in Germany today. It shows a stone relief of the city's patron saint, St. Martin , from 1441. Many townhouses, especially around the market, date from the 15th to 17th centuries and have been carefully restored. Today the market square offers a picturesque backdrop.

The approximately 2.7 km long, 7.5 to 10 m high and at its base an average of 3 m thick city wall was provided with towers in strategic places and reinforced by hurdles in at least five places , but was opened during the Seven Years' War on the orders of French occupying forces dragged about two thirds of its height. Ten of the former 23 defensive towers are still standing today: Frauenturm, Grauer Turm , Grebenturm, Rosenturm, Jordan Tower, Regilturm, Turm am Bad, Bleichenturm, Pulpit and Winter Tower (the latter four as part of the wall around the so-called Neustadt). With a height of 38.5 m, the "Gray Tower", first mentioned in 1274, is the highest still standing urban watchtower in Germany. Only here is a short piece of the former top of the wall with battlements, which was restored in the 1980s. Only the stumps of the tower still exist: the old tower, the Kalars, the Petersturm, the Nadelöhrturm, the Zuckmantel, the stone cast tower and the pavilion and two nameless towers. The moats in front of the wall have almost completely disappeared today, with the exception of small remains on the west side of the old town. Most of the city gates with their barbicans were demolished in the first half of the 19th century because they hindered traffic: the hospital gate in 1823, the Werkeltor in 1829, the Fleckenborntor (at the foot of the "Ziegenberg") in 1834 and the magnificent gate tower of the Haddamartor in 1838.

Outside the city, there are still five of the former seven wards , which were built in the second half of the 14th century or 1425 (Galbächer Warte) as a guard post and, with their circular walls, as places of refuge and were partly connected by land defenses : Obermöllricher ( Unröder) Warte, Kasseler Warte (near which the imperial general Piccolomini had his military tent in 1640), Hellenwarte, Eckerichswarte and Galbächer (Galberger) Warte. The Auewarte was demolished in 1937 when the military airfield was being built; the Holzheimer Warte fell into disrepair in the 18th century.

Wall towers

Waiting

history

Boniface, Donareiche and city foundation

The starting point for urban development is the founding of the church by Bonifatius (Winfrid). According to the Vita Sancti Bonifatii of Willibald of Mainz was Boniface to 723/24 near Gaesmere (Geismar , today a district of Fritzlar) the Donareiche on today's city of Fritzlar, cases. With the felling of the oak consecrated to the god Donar , which was considered one of the most important Germanic sanctuaries, Bonifatius wanted to demonstrate the superiority of the Christian god to the Chats and made a prayer house consecrated to St. Peter at an unspecified place from the wood of the tree (oratorium ) erect.

The Bonifatius-Vita des Willibald mentions the construction of a church consecrated to St. Peter and a monastery around 732 in Friedeslar (Fritzlar) under Abbot Wigbert , in the place of which today's Fritzlar Cathedral was built. Due to the patronage of St. Peter , it is generally assumed that the first house of prayer consecrated to St. Peter was located in the same place as today's cathedral.

The exact location of the Donareiche is unknown, but the ostensibly different location information in the written tradition - "near Geismar" and "in Fritzlar" - can be explained by the fact that the place Frideslar was only created after the building of the prayer house and the foundation of the monastery "At Geismar" lies. It is therefore mostly assumed that these place names refer to the same place in principle. The first house of prayer of Boniface was built on the site of the Donareiche or in its immediate vicinity on today's cathedral hill. The site of the pagan sanctuary was thus taken into possession, the laborious transport of the timber cut from the oak to another building site was no longer necessary, and the place - as happened later - could easily be expanded for fortification.

In the following period the monastery developed into an important center of ecclesiastical and secular learning. Charlemagne , from whose time the first imperial palace in the city dates, gave the monastery, which had been assigned to him by Bishop Lullus of Mainz after it was destroyed by the invasion of the Saxons in 774, imperial protection and considerable lands, and with the elevation to the Imperial abbey in 782 began the rapid development of the surrounding settlement into a city. The monastery was converted into a collegiate monastery at the latest in 1005 after the missionary task assigned to it by Boniface had been fulfilled . The canons no longer lived together as a monastery, but in their own houses (curia) , of which some noteworthy buildings from the 14th century still adorn the cityscape. The pen was dissolved in 1803.

Heinrich I and medieval imperial politics

The strategically important location of the city, in the border area between Franconian and Saxon settlement areas and at a crossroads of important early medieval roads from different directions, made Fritzlar a preferred place of residence for the German kings and emperors in Hesse, especially in the 10th and 11th centuries. The imperial palace, which was probably built at the time of Charlemagne , is no longer there today. Until the end of the 11th century, Fritzlar was the location of important diets, assemblies, synods and visits by the emperor.

In a battle near Fritzlar in 906, Count Konrad the Younger from the family of the Konradines succeeded in decisively defeating his Babenberg rivals for supremacy in Franconia, which had attacked him there and, as his father Konrad the Elder, in the fight had fallen in order to secure the ducal dignity of Franconia. Five years later, Konrad was elected King of the East Franconian Empire in Forchheim as Konrad I and successor to his uncle Ludwig the child . The Conradin castle at the western end of the city of Fritzlar thus became the royal palace.

Probably the most important Reichstag in Fritzlar was that of 919, at which Heinrich I , Duke of Saxony, was elected King of the East Franconian Empire on May 12th . King Conrad I died in December 918 without a son and had instructed his brother, Margrave (and after Konrad's death, Duke) Eberhard von Franken to propose the crown to Heinrich, since in his opinion only Heinrich was able to resolve the dispute between Franconia and to settle Saxony, to reintegrate the southern German tribal duchies of Bavaria and Swabia as well as Lorraine firmly into the empire, and to maintain imperial unity. Eberhard, and subsequently Duke Burchard I of Swabia, supported the election of Heinrich, but Duke Arnulf I of Bavaria did not submit until Heinrich marched into Bavaria with an army in 921. Heinrich was the first Saxon to succeed the Frankish descendants and successors of Charlemagne on the throne of the East Frankish Empire.

In the period that followed, the city was the location of imperial and princely days on several occasions, and the emperors, especially the Ottonians and Salians , held court, council and court in the city at least 15 times until 1145. The Fritzlar Reichstag of May 953, chaired by Otto the Great , imposed severe penalties against the Emperor's son Liudolf and his co-conspirators such as the Duke of Lorraine, Konrad the Red , and the Archbishop of Mainz, Friedrich . During the disputes between Heinrich IV. And the rival king Rudolf of Swabia , Fritzlar was the place of negotiations between the parties at least three times in 1078/79, until Rudolf laid the city and the royal palace there in rubble and ashes in autumn 1079.

The three synods held in Fritzlar in 1118, 1244 and 1259 were also significant. At the general synod in Fritzlar of 1118, chaired by the papal cardinal legate Kuno von Praeneste , the papal ban against Emperor Heinrich V , who was involved in a new investiture dispute with the pope lay, proclaimed and confirmed. At the same time, Prince-Bishop Otto von Bamberg was removed from office by the papal party because, as Chancellor of the Reich , he had remained loyal to his emperor in the dispute with Rome. At the same synod, Norbert von Xanten , who later founded the Premonstratensian Order and later Archbishop of Magdeburg , successfully defended himself against the accusation of heresy , which the official church had made as a traveling preacher because of his charismatic reform and penance sermons , by calling on John the Baptist . The general synod on May 30, 1244 repeated the papal occupation of Emperor Frederick II and the archbishopric-Mainz occupation of the city of Erfurt with the ban and issued 14 statutes to strengthen church order and discipline. The Synod of 1259 also issued a number of ordinances on questions of ecclesiastical administration and discipline; This included the expulsion of the begarians and beguines as well as the decree that on Good Friday no Jew should be seen looking out of a window or standing in the door.

The imperial politics touched Fritzlar again in the year 1400. Duke Friedrich von Braunschweig and Lüneburg was proposed at the Fürstentag in Frankfurt as counter-king to Wenzel von Luxemburg , but Archbishop Johann II. Von Mainz favored the Count Palatine Ruprecht instead , so that the two parties were in conflict left Frankfurt. On his way home on June 5, 1400 near Fritzlar, near the present-day village of Kleinenglis , Friedrich was born by Count Heinrich VII von Waldeck and his cronies Friedrich III. von Hertingshausen and Konrad (Kunzmann) von Falkenberg murdered - all of them feudal men and ministerials from Kurmainz. Wenzel was allowed to keep his crown until August 20, before he was deposed and replaced by Ruprecht. The so-called Kaiserkreuz von Kleinenglis erected at the scene of the crime has been a reminder of the murder of 1400 since the 15th century .

Territorial bone of contention

Due to its location in the border area between Franconian and Saxon lands, later as an archbishopric Mainz enclave in the Landgraviate of Thuringia and then in the Landgraviate of Hesse , the city was repeatedly the cause, starting point or place of armed conflicts - between Saxony and Franconia, between spiritual and secular Lords and between Catholic and Protestant princes. It was often besieged, conquered and sacked several times, but always rebuilt.

The first destruction occurred in 774, during the Saxon Wars of Charlemagne . When Karl was in Italy, the Saxons invaded northern Hesse and besieged the Büraburg, where Fritzlar's population had sought protection. Although they were unable to take the castle, they sacked the city and burned it down. Only Wigbert's stone basilica remained intact, which then led to the legend that two angels appeared and chased away the enemies. The city was immediately rebuilt, and a church assembly took place there as early as 786, at which the third Archbishop of Mainz was elected. From then until 1051 the Fritzlar abbots were appointed auxiliary bishops in Mainz.

In the years from 1066 to 1079, the monastery, office, palatinate and city of Fritzlar gradually became the property of the Archbishops of Mainz through gifts from Emperor Heinrich IV. And the city, which had been the most important place in Niederhessen until then , was soon lost its importance as a place of imperial politics. Affiliation to Mainz only ended with the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of 1803. The city coat of arms, the (double) red Mainz wheel on a silver background, reminds of this centuries of affiliation .

Before that, however, Henry IV's dispute with Rome and with the anti-king Rudolf von Rheinfelden, supported by the Pope, had even worse consequences for Fritzlar. Heinrich, who often stayed in Fritzlar in the Palatinate, had again quartered in Fritzlar in the winter of 1078/79. A Saxon army, partisans of Rudolf, attacked him there in the summer of 1079. He managed to escape, but the city was captured and completely devastated. According to Archbishop Wezilo of Mainz, the place was still practically desolate in 1085 , before the rebuilding began.

In the following centuries Fritzlar (as well as Naumburg , Hofgeismar and Amöneburg ) was the cornerstone of Mainz's territorial policy in Northern Hesse, and the city became the focus of repeated military conflicts between the Landgraves of Thuringia and later of Hesse on the one hand and the Archbishops of Mainz on the other. Heinrich Raspe's brother, Konrad von Thuringia , who as Count of Hesse (Gudensberg) administered the Hessian parts of the then Landgraviate of Thuringia, conquered Fritzlar on September 15, 1232 after a three-month siege; the city was completely looted and cremated and most of the residents were killed. Old chronicles report that Konrad had already set out to retreat when some "loose women" from the city wall angry with him with extremely immoral gestures that he ordered another storm and the destruction of the city. Konrad was banned from the papal for this , went to Rome to apologize, entered the Teutonic Order in 1234 , and came back to Fritzlar on June 29, 1238 to pay a public church penance and to rebuild the with his own money and money obtained from indulgences Fund collegiate church. The city immediately began to rebuild, strengthening the fortifications, with the city wall being pushed out further to the east to make room for the new Franciscan monastery and the Teutonic Order, erecting a number of additional wall towers and seven waiting areas at strategic points around the city. As early as 1244, when Archbishop Siegfried III. held a general synod in Fritzlar on May 30, the collegiate church was completely repaired.

Nonetheless, the city suffered considerable damage again when Landgrave Heinrich I called upon Fritzlar's Archbishop Werner von Eppstein , reinforced by troops from Count Gottfried VI, near Fritzlar . von Ziegenhain , defeated with a landsturm army. Heinrich, grandson of St. Elisabeth , was proclaimed Landgrave on Mader Heide in 1247 and has since called himself Landgrave of Hesse, but had to assert himself against the strong presence of the Archdiocese of Mainz in his north Hessian sphere of influence, as Mainz also claims to the Death of Heinrich Raspe raised the vacant rule over northern Hesse, which had been a Mainz fief since about 1120 and whose reversal Mainz now demanded.

Economically, it initially brought the city certain advantages to be Mainz. The archbishops settled free merchants, the city became the first mint in Hessen, and it ranked as a trading center for cloth, furs and spices before Kassel. The first city wall was built in the years 1184-1196. Beginning in 1280, the so-called New Town was built, which was surrounded by its own city wall and remained legally independent until the sixteenth century. The city's water supply was secured by a system of wooden pipelines through which water was pumped from the Eder and the Mühlengraben into wells and water reservoirs on the market square and the cathedral square.

In connection with the Mainz schism from 1346 to 1353, there was another battle between Mainz and Hesse in May 1347 on the plain between Fritzlar and Gudensberg , in which Landgrave Heinrich II decisively defeated Archbishop Heinrich von Virneburg . The latter was in April 1346 because of his partisanship for Emperor Ludwig IV of Pope Clement VI. , who in that year promoted the election of Charles IV to Rex Romanorum , was deposed and replaced by Gerlach von Nassau . Heinrich von Virneburg ignored the papal decision and argued with Gerlach about the archbishopric until his death in 1353. Landgrave Heinrich supported Gerlach, and after the death of Heinrich von Virneburg, Mainz, because of this battle and Gerlach's promises to Landgrave Heinrich, had to take its Lower and Upper Hessian possessions from the Landgraves as fiefs; only Fritzlar, Amöneburg and Naumburg remained in possession.

The final military defeat of the archbishops against the Hessian landgraves in the 15th century - with the decisive victories of Landgrave Ludwig I over the troops of Archbishop of Mainz Konrad III. von Dhaun on July 23, 1427 near Fritzlar (on the Großenengliser Platte between Kalbsburg and today's Wüstung Holzheim ) and on August 10, 1427 near Fulda - and the beginning of the Reformation in the 16th century then brought a decline in the importance of the city which has now been overtaken by Kassel . As early as 1438, St. Peter's Abbey came under the protection of the Landgrave. (One year later he became the patron of all Mainz possessions in Hesse.) After the peace in Augsburg , Fritzlar and the neighboring villages of Unthought and Rothelmshausen remained Mainz and Catholic, while the surrounding area became Protestant. From this arose the complete sectarian and largely economic isolation of the city.

Twice more, during the Mainz collegiate feud from 1461–1463 and during the Hessian fratricidal war 1468/69, the city almost became Hessian. Both times she successfully defended herself against the pledge intended by the Archbishop of Mainz Adolf II of Nassau to Landgrave Heinrich III. from Hessen-Marburg . The pledge deeds had already been issued in both cases and given to both the landgrave and the city, but the city council refused to recognize them. He pursued a clever policy, on the one hand playing off the warring brothers Ludwig II of Hessen-Kassel and Heinrich von Hessen-Marburg against each other and on the other hand successfully intervening in the cathedral chapter of Mainz against the archbishop's plans. Since Fritzlar was still well armed and armed, it escaped the fate of Hofgeismar , which, despite similar resistance, was militarily overwhelmed and taken over by Landgrave Ludwig.

Plague and wars

In 1483 the plague raged . Of about 2200 inhabitants only about 600 survived. The Black Death subsequently passed through the city several times, especially in the years 1472, 1558, 1567, 1585, 1597, 1610/11 and 1624. It was not until 1740 that the city returned 2000 inhabitants.

The Thirty Years' War brought 1,621 looting by troops of the Duke Christian of Brunswick, and on September 9, 1631, the conquest and looting by Protestant troops of the Hessian Landgrave William V , connected to the extortion severe Kontributionszahlungen. On his retreat after the Battle of Breitenfeld , Tilly came to Fritzlar, which the Hessians had left in time, but occupied again immediately after he moved on. They stayed until 1648, although several times imperial troops forced them to withdraw temporarily. On August 14, 1640, imperial troops under Archduke Leopold Wilhelm and General Piccolomini occupied the city, and on August 20, a Swedish army appeared under Field Marshal Johan Banér , although the imperial troops were not ready to face a great battle. After the Swedes and the Imperialists withdrew, the Hessians returned. In 1647 imperial and Bavarian troops under Generals von Gronsfeld and Melander occupied the city again, were expelled from Sweden and Hesse under General Wrangel and the French under Turenne , but returned immediately and did not withdraw until the spring of 1648. Hessian occupiers came again to the city, which they did not finally vacate until August 31, 1648. At the end of the war in 1648, the city's population had fallen from 2,400 in 1618 to only 400, and it took 70 years for the city and the monastery to pay off the debts of the war years.

The Seven Years War brought even more severe devastation. Hostile Hessians, Brunswicks, Hanoverians and English and then allied French and Württembergians occupied the city in frequent alternation. From February 12 to 15, 1761, there was heavy fighting between the approximately 1,000 French and Irish troops in the city under General Vicomte de Narbonne-Peletor and a 6,000-strong siege army under the Hereditary Prince of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand , a nephew of Frederick the Great . After fighting on February 13th, which was particularly costly for the Hanoverians, the besiegers gathered another 15,000 men and strong artillery in the north of the city on February 14th and began a heavy artillery bombardment, which continued with incendiary shells on February 15th and caused great destruction. General Narbonne surrendered on the afternoon of February 15 and received free retreat with his men. The victorious allies moved in, raised a contribution of 10,000 thalers, and began demolishing the top of the walls and battlements. They left the city only when a strong French army approached on March 9th. In 1762 the French continued to destroy the fortifications by demolishing towers and parts of the wall, filling in the two northern moats and devastating the vineyard on the steep north slope of the Edern, which today is only remembered by street names. Fritzlar ceased to be a "permanent city". The centuries-old viticulture also came to a standstill with the clearing of the vineyards.

Witch hunt

There is so far no comprehensive description of the witch hunt in Fritzlar in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Some case files are in Vienna , others in Würzburg . Processes from the years 1596, 1616 and 1626–1631 are known. The names of 62 known victims of witch trials in Fritzlar are listed on an information board in the Gray Tower, a considerable number for a community of less than 2000 inhabitants at the time; however, a higher number of victims must be assumed. During the Thirty Years War, shortly after a plague epidemic from 1627 to 1629, seven men and 25 women were burned as witches and warlocks. In 1656, the Mainz government made inquiries about the whereabouts of funds that should have flowed to the chamber from the Fritzlar witch trials between 1626 and 1630 with their chief magistrate von Amöneburg and Fritzlar.

Modern times

After the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss 1803 Fritzlar, together with the offices of Naumburg , Amöneburg and Neustadt, which had also been electoral Mainz until then , was annexed to Hessen-Kassel as a nominal principality of Fritzlar . Landgrave Wilhelm IX. had already had these offices and the Volkmarsen in the Electorate of Cologne occupied by the military in September / October 1802 and took legal possession on December 1, 1802. This was based on the agreements of the Peace of Lunéville (February 9, 1801) and the Franco-Russian Compensation Plan (August 18, 1802) and in anticipation of the main conclusion of the Reich Deputation. From 1807 to 1813 Fritzlar was the administrative seat of the canton Fritzlar within the Kingdom of Westphalia . In 1821 Fritzlar became the district town of the Fritzlar district in the Electorate of Hesse-Kassel and remained so after the annexation of Kurhesse by Prussia in 1866. During a brief administrative reform from 1848 to 1851, the city was the administrative seat of the Fritzlar district, to which the previous (and subsequent) districts Fritzlar, Homberg and Ziegenhain belonged.

During the Austro-Prussian War at the end of June 1866, first Trier Hussars and then Prussian artillery and infantry occupied the city, but without fighting or destruction.

In 1932 the district was merged with the neighboring district of Homberg to form the Fritzlar-Homberg district (license plate from 1956 FZ).

In the Second World War the 17./18. May 1943 of particular importance for the place. After the bombing of Edertalsperre a devastating tidal wave flowed through the low-lying neighborhoods. The Easter holidays in 1945 were also significant days in local history. The heads of American tank units , coming from Bad Wildungen through the Edertal, reached the outskirts on Good Friday. Around noon, the German defenders blew up the 13th century stone bridge over the Eder. About 40 German and 120 American soldiers were killed in the following 36 hours before the city was occupied by the Americans on Easter Sunday. The German troops had withdrawn to Werkel , and this village was largely destroyed by American artillery fire in the ensuing fighting.

After the end of the war, a DP camp for so-called Displaced Persons (DPs) existed in the Watter barracks, which were no longer used by the military, from 1946 to 1949 . It was initially occupied by former forced laborers , then by Jewish concentration camp survivors and homeless people. From 1953, a branch of the radio manufacturer Heliowatt was located in part of the former barracks .

In the course of the territorial and administrative reform of 1974, the Fritzlar-Homberg, Melsungen and Ziegenhain districts were combined in the new Schwalm-Eder district , whose administrative seat was moved to Homberg (license plate number HR).

Incorporations

As part of the regional reform in Hesse on December 31, 1971, the previously independent villages of Cappel, Geismar, Haddamar, Lohne, Obermöllrich, Rothhelmshausen, Ungedanken, Wehren and Werkel were incorporated . On July 1, 1972, a sub-area of the municipality of Wabern was added with a population of just over 300 at that time. The former Waldeck town of Züschen followed on January 1, 1974 by state law.

Monasteries, churches and synagogues

The Benedictine monastery of Bonifatius and Wigbert and the St. Petri Monastery that emerged from it and was dissolved on May 28, 1803, were not the only ecclesiastical institutions that were established in the city over the centuries.

In 1145 a hospital for the poor was founded, which by 1254 at the latest became an Augustinian convent with a church consecrated to St. Catherine . This monastery was abandoned in the 16th century. The Ursuline monastery building , which today serves as a school, was built in its place between 1713 and 1719 . The Katharinenkirche still exists today.

After the total destruction of the city by Konrad von Thuringia in 1232, the Franciscans asked for and received permission in 1237 to build a monastery and, due to lack of space, to build right up to the city wall. The Fritzlar Franciscan monastery was consecrated in 1244. When Pope Leo X recognized the split in the Franciscan order brought about by the poverty dispute in 1517, the monastery confessed to the order of the Minorites (conventuals), who were allowed to share property. In 1548, when the Lutheran Reformation had many followers in the city, the monastery had to close, and in 1552, when the Landgrave Hessian troops occupied the city and the Reformation was introduced, the monks had to leave the city. The landgraves' occupation ended in 1555 after the religious peace of Augsburg, and the city remained Catholic. However, on January 14, 1562, the cathedral dean of Mainz had to end an uprising of the citizens who were inclined to the Protestant side with 200 horsemen and 300 foot soldiers. With the Counter-Reformation , Jesuits first came to the monastery in 1615 and Minorites again in 1619. After secularization , it was put on extinction in 1804 and finally abolished in 1811; the entire monastery property, including the church, was transferred to the city of Fritzlar. The large Gothic monastery church, completed around 1330, was acquired in 1817/1824 by the Protestant township founded a few years earlier and has been a Protestant town church since then , while the other monastery buildings now house a modern hospital.

The Teutonic Order already owned Fritzlar in 1219 and received larger goods in what is now the Obermöllrich district through donations from Landgrave Heinrich Raspe of Thuringia in 1231 . But when three years later the nunnery Ahnaberg transferred his goods in Obermöllrich the German Order in long lease, 1234, the Order established in a Obermöllrich Coming , the first to the Bailiwick belonged Thuringia. From 1255 on, she was one of the nine coming of the Ballei Hessen, which had split off from Thuringia and was now independent. In 1304 the order moved the commander to Fritzlar. The commandery building from this time was demolished in 1717. In its place, the Landkomtur der Ballei Hessen, Count Damian Hugo von Schönborn , built the so-called Deutschordenshaus, which is still in private hands today. The former tithe barn of the order, built in 1238, is now a culture barn Fritzlar venue for exhibitions, concerts, theater performances, etc.

The Fraumünster Church , located a little east of the old town , first mentioned in 1260, was possibly part of a short-lived nunnery; this is indicated by the name and some documents from the 14th century. However, this has not been proven and is rather doubted today. There were frequent disputes about the church, especially after the introduction of the Reformation in the Landgraviate of Hesse in 1527, as it belonged to the Hessian village of Obermöllrich , but was in Kurmainzisch-Fritzlarer territory.

In 1711 the Ursulines from Metz founded a monastery in Fritzlar on the site of the Augustinian convent that was abandoned in the 16th century . In 1713 they laid the foundation stone for a school for girls . The monastery building was completed and occupied in 1719, and the former Katharinenkirche was consecrated as a monastery church in 1726. During the time of Bismarck's Kulturkampf , the sisters were expelled from the country from 1877 to 1887 (the monastery building was used as a district office), but then in 1888 they obtained state recognition by Prussia. The period of National Socialism brought new difficulties: the primary school had to be closed in 1934, the lyceum in 1940, and in 1941 the monastery was confiscated and the nuns expelled by the Gestapo . After her return in November 1945, the monastery and school experienced a steady upswing, but the monastery had to be closed in 2003 due to a lack of children. Today the Ursuline School is a cooperative comprehensive school with an upper level.

In 1989, a Premonstratensian branch was founded in Fritzlar by the Austrian Geras Abbey , which existed as the St. Hermann Josef Priory from 1992 , but was dissolved by the Abbot of Geras with effect from July 1, 2010 as a result of a sexual abuse scandal.

At least six former places of worship have disappeared from the cityscape over time, including the following:

- The Jesuits, who had lived in the city since 1615 and lived in a house next to the St. John's Chapel, were assigned the St. Nicholas Church, first mentioned in 1266 and owned by the city since 1493, in 1578 today's post office. Originally it was probably the place of worship of the city's oldest merchants' guild. After the expulsion of the Jesuits in September 1629, when the troops of the Hessian Landgrave Fritzlar occupied the church, the church gradually fell into disrepair. The last still standing church tower, on which the city clock was attached, was demolished in 1755.

- On the north side of the cathedral square, where the Protestant parish office is today, was the St. John's Chapel, which probably belonged to the former royal palace. It was assigned to the cathedral altarists in 1463, lost its function as a place of worship in the Seven Years War, was then used as a storage room, used at the beginning of the 19th century by the still small Protestant parish, rented out by the city as a horse stable in the Napoleonic period, and in 1848 because of it Dilapidation canceled.

- At the place of today's tax office stood the St. George Church in front of the city walls, to which the first city hospital, a leprosarium , was attached. In 1308 the hospital was moved to the Mühlengraben in front of the Neustadt. The hospital chapel still stands there today.

- The Marienkapelle, mentioned in the 16th century, stood in front of the gate, of which nothing remains.

- Synagogues:

- The “old synagogue” existed on Nikolausstrasse from 1823 to the end of the 1890s.

- From 1897 to 1939 the “new synagogue” stood on Neustädter Strasse.

Garrison history

The history of the garrison town of Fritzlar began with the incorporation of the city into the Electorate of Hesse-Kassel . As early as 1803 a squadron of the Hessian electoral dragoon regiment "Landgraf Friedrich" was moved from Wolfhagen to Fritzlar, soon followed by other parts of the regiment. In 1806, after the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, Marshal Mortier occupied the neutral electorate. The small but well-equipped and trained Kurhessian army was disarmed and dissolved or incorporated into the army of the Kingdom of Westphalia (1807-1813) newly created by Napoléon Bonaparte .

After the restoration of the electorate, the Hessian 1st Hussar Regiment came to Fritzlar in 1815. In 1827 the city had the wedding house set up as a "cruet" for the regiment for 2,000 thalers. In 1840 the garrison was disbanded. During the Hessian constitutional struggles, Fritzlar was occupied by so-called " penal Bavarians " in 1850/51 .

After the annexation of Hessen-Kassel by Prussia in August 1866, Fritzlar became a Prussian garrison in 1867, with the billeting of first cavalry and then the cavalry division of the 1st Kurhessian Field Artillery Regiment No. 11 . In 1870/71 the regiment took part in the battles at Weißenburg (August 4, 1870), Wörth (August 6, 1870) and Sedan (September 1, 1870) and in the siege of Paris . (A monumental memorial in memory of the members of the regiment who died in the Franco-Prussian War is in Alsace near Wörth an der Sauer on the road to Elsasshausen.) From 1872 until the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, the regiment's riding division was back in Fritzlar (the staff and the other two departments in Kassel). The large team block, called Watter barracks from 1935 , in the extensive barracks complex on the northern edge of the city was moved into in 1890.

The city remained a garrison in the interwar years, now as the location of the 11th (mounted) battery of the 5th artillery regiment of the Reichswehr . During the armament in the time of National Socialism , the garrison was considerably strengthened. The old artillery barracks on Kasseler Strasse, now renamed Watterkaserne, housed parts of the artillery regiments 5, 9, 29, 45 and 65 and various training and replacement units. A 1935-1938 newly created 300-hectare airbase in the Eder valley south of the city was from April 1938 location of fighter planes and 1944-45 of night fighter pilots ; the future Federal President Walter Scheel was temporarily stationed in Fritzlar as a young officer. The Auewarte, one of the original seven waiting areas , fell victim to the construction of this facility as early as 1937 . From 1941 to 1944 the air base served as a second plant for Dessauer Flugzeug- und Motorenwerke AG ; on October 1, 1943, the prototype of the new "Ju 352" made its first launch there.

After the end of the Second World War, the spacious old artillery barracks were abandoned and their buildings were made available for civil purposes (including DP camps , refugee accommodation , commercial settlement, school, sports hall, riding arena, winter quarters for a tent circus ), while the air base was used by occupation troops has been. Initially, the US 404th and 365th Fighter Group with P-47 Thunderbolt fighter aircraft were stationed there from April to June and July 1945, respectively . This was followed by the 366th Fighter Group from September 1945 to August 1946 and the 27th Fighter Group from August 1946 to June 1947, both also with Thunderbolts . From 1947 to 1951 the staff and the 1st Battalion of the 14th US Constabulary Regiment (reclassified in 1948 and renamed the 14th Armored Cavalry Regiment) were on the former air base. In 1951 the American troops moved to Fulda and Bad Hersfeld , and in their place French troops (3rd Regiment of the Spahis algériens ; parts of the 5th Hussar Regiment , with AMX-13 reconnaissance tanks) came to Fritzlar.

With the formation of the Bundeswehr in 1956, the occupation troops withdrew, and German grenadier and artillery battalions and, from 1957, army aviators moved in in their place . The air base thus became the Fritzlar Army Airfield . In 1997 the Air Mechanized Brigade 1 was put into service in Fritzlar ; this was the first time that the army received quickly deployable and air-mobile infantry forces. Since 2002, the medical management center 210 was stationed in Fritzlar. Finally, in 2006, as part of the reorganization of the Bundeswehr, the staff and the staff company of Air Movable Brigade 1 and the combat helicopter regiment 36 "Kurhessen" belonging to this brigade from 2006 to 2013 with combat helicopters of the type BO 105 were stationed in Fritzlar; the first three copies of the intended Eurocopter Tiger were only delivered to the regiment in April 2011. Airmobile Brigade 1 was disbanded on December 17, 2013, and the 36th Combat Helicopter Regiment has been under the Airmobile Operations Division since then .

Religions

General

Religion has played a very important role in the history of the city, starting with the felling of the Danube Empire and the building of the first chapel by Boniface. With the beginning of the Reformation , which was supported by the Landgraves of Hesse, Fritzlar, the archbishopric of Mainz, and the neighboring Mainz villages of Ungedanken and Rothhelmshausen , which had been acquired by Fritzlar Abbey in 1308 and 1324, fell into a total religious isolation, which also had significant economic consequences. The majority of the population of this enclave was Catholic until the middle of the 20th century. In the course of the ongoing urban development and with the influx of administrative employees, the military and the service industry, however, the proportion of the Protestant population gradually grew, until after the Second World War it was due to the admission of refugees and subsequently to immigration from the surrounding areas half of the total population grew.

The Jewish community

A Jewish community already existed in the Middle Ages (around 1100), but was destroyed during the persecution of the Jews in the plague time of 1348/49. Towards the end of the 14th century a new community emerged, and a document from 1393 states that Jews are and should continue to be considered citizens as they have been for ages. Most Jewish families left the city after 1469, although Archbishop Adolf II of Mainz did not officially expel all Jews from the area of his archbishopric until the next year. In the 17th / 18th Few Jewish families lived in the city in the 19th century, and a Jewish community did not emerge again until the 19th century. Around 1860 the number of Jewish residents reached its highest level with 139 people. A synagogue had existed since the end of the 18th century. A new synagogue, inaugurated on June 30, 1897, was destroyed in the November pogroms of 1938; The majority of SS men from Arolsen and men carted over from neighboring villages stood out. Numerous Jewish residents were murdered in extermination camps after their deportation from Fritzlar, among them the last prayer leader and teacher of the community, Gustav Kron , and his wife. Today only the large Jewish cemetery on Schladenweg, some street names (for example Judengasse , Am Jordan ) in the old town and a memorial plaque on the site of the destroyed synagogue as well as the recently designed so-called " stumbling blocks " (paving stones with a brass plate on which the names of the murdered Jews were engraved) to these fellow citizens.

politics

City Council

The local elections on March 6, 2016 produced the following results, compared to previous local elections:

| Parties and constituencies |

% 2016 |

Seats 2016 |

% 2011 |

Seats 2011 |

% 2006 |

Seats 2006 |

% 2001 |

Seats 2001 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDU | Christian Democratic Union of Germany | 45.8 | 17th | 47.8 | 18th | 47.7 | 18th | 44.9 | 17th | |

| SPD | Social Democratic Party of Germany | 31.5 | 12 | 33.5 | 12 | 34.2 | 13 | 37.2 | 14th | |

| FWG | Free community of voters Fritzlar | 10.5 | 4th | - | - | 8.8 | 3 | 8.5 | 3 | |

| GREEN | Alliance 90 / The Greens | 7.0 | 2 | 15.0 | 6th | 5.5 | 2 | 5.6 | 2 | |

| FDP | Free Democratic Party | 5.2 | 2 | 3.7 | 1 | 3.8 | 1 | 3.9 | 1 | |

| total | 100.0 | 37 | 100.0 | 37 | 100.0 | 37 | 100.0 | 37 | ||

| Voter turnout in% | 53.4 | 52.9 | 58.6 | 60.4 | ||||||

mayor

Mayor Karl-Wilhelm Lange ( CDU ) was re-elected on March 26, 2006 with 65.8% of the vote. The non-party candidate Hans Mertens received 34.2% of the vote.

In the mayoral election on January 29, 2012, Hartmut Spogat (CDU) prevailed against Gerlinde Draude (SPD) and Joachim Frank (non-party). Spogat received 53.9% of the vote, Draude 42.5 and Frank 3.7. The incumbent Karl-Wilhelm Lange did not run for mayor after 18 years. Spogat took over the office on May 1, 2012.

coat of arms

Blazon : "In silver, two inclined eight-spoke red wheels connected by a red cross."

With the double wheel , the Fritzlar coat of arms is based on that of Mainz and thus shows the city's centuries of political affiliation with the Archdiocese of Mainz .

Town twinning

Burnham-on-Sea / Highbridge in County Somerset (Great Britain) and Casina in the Emilia-Romagna region (Italy) are sister cities of Fritzlar.

Economy and Infrastructure

The city is primarily an administrative and service center, with public and church authorities, a district court , schools, hospitals, etc. There are also shopping centers, shops, restaurants, cinemas, sports facilities, repair shops, doctors and other private service providers. Thanks to its picturesque inner city and the “Domstadt-Center” shopping center, Fritzlar is one of the most popular shopping cities in the region.

The largest employer is the Bundeswehr . This is followed by a canning factory belonging to the Hengstenberg company , which produces sauerkraut , red cabbage , cucumber , vinegar and fine- sour vegetable specialties in particular . The area around Fritzlar is one of the main growing areas for white cabbage in Germany, and the Fritzlar plant is the world's largest sauerkraut factory.

traffic

The most important transport connections are as follows:

- The railway line Wabern – Brilon Wald opened in 1884 . The section that used to run from Bad Wildungen to Korbach is now largely closed. The section of the route from Bad Wildungen to Wabern has been operated by the Kurhessenbahn since 2008 . In Wabern there is a connection to the Main-Weser-Bahn to Kassel and Frankfurt am Main .

- Motorway Kassel – Marburg ( A 49 )

- Federal highways 3 , 253 and 450

- Express bus route Kassel – Fritzlar– Bad Wildungen

- Remote bus of BEX to and from Berlin and Frankfurt / Main (once a day) from Fritzlar Ave.

Long-distance cycle routes

The following cycle paths lead along the Eder :

- The 180 km long Eder cycle path begins in the Rothaargebirge in North Rhine-Westphalia and is called here Ederauenweg. The largest part leads through Hesse and is then called the Eder cycle path . It follows the course of the Eder to its confluence with the Fulda (river) near Guxhagen .

- The Hessian long -distance cycle path R4 (north-south cycle path) begins in Hirschhorn am Neckar and runs for about 385 km from south to north through Hesse, along from Mümling , Nidda and Schwalm to Bad Karlshafen an der Weser .

Educational institutions

- High school: König-Heinrich-Schule

- Cooperative comprehensive school with upper level: Ursuline School (Catholic; formerly sponsored by the Ursuline Order, current sponsor: Diocese of Fulda)

- Secondary and secondary school: Anne Frank School

- Vocational and technical college: Reich President Friedrich Ebert School

- Primary school: school on the towers

- Primary school: School to Obersten Holz, Obermöllrich-Cappel

- Primary school: Rainbow School, Lohne – Züschen

- School for the practically imaginable : School at the cathedral

- Nursing school

- German training center / theological seminar of the Free Church Federation of the Congregation of God

Leisure and sports facilities

- Sports and leisure park in the Alte Wildunger Straße

- Outdoor pool (heated) in the Ederau

- Horse show in the Ederau

- Schützenhaus ( small caliber and pistol) in the Ederau

- Tennis courts in the Ederau and on the Roten Rain

- Sports halls in the school center and at the Ursuline school

- Football stadium on the Red Rain

- Marked hiking trails in the entire area

- Nature trail in the Ederau

Culture and sights

Museums

- History and local history museum in the regional museum wedding house

- Cathedral museum with cathedral treasure and the important Kaiser-Heinrich-Kreuz

Buildings

- Collegiate Church of St. Peter ("Cathedral", around 1085/90)

- "Libra" (former collegiate hall, around 1234)

- Gothic town church (former Minorite monastery church , 1244)

- City wall and defense towers (12th-14th centuries)

- Gray Tower , with museum (13th century)

- Town hall (from 1109, oldest office building in Germany)

- Market square with Roland's fountain and former mint

- Wedding house (around 1580/90), the largest half-timbered building in Northern Hesse, since 1956 a museum for prehistory and early history, folklore and town history

- Curia (14th - 15th centuries)

- Half-timbered houses (15th-18th centuries)

- Former convent of the Franciscan ( Friars Minor ) (13th century), today Hospital

- Convent of the Ursulines (1719), today a high school

- Katharinenkirche (around 1300), former monastery church of the Augustinians and Ursulines

- Fraumünster Church

- former Teutonic Order House

- Hardehauser Hof

- Waiting (watchtowers out of town)

Excursion destinations in the vicinity

- Büraberg (castle and monastery from the 7th and 8th centuries, preserved excavations, Brigidakirche, Stations of the Cross)

- Stone Age settlement near Geismar

- Donarquelle , mineral spring near Geismar

- Stone chamber grave or gallery grave near Züschen (around 2000 BC)

- Bad Wildungen with Friedrichstein Castle

- Felsberg with rock castle

- Heiligenberg (near Gensungen )

- Gudensberg with Obernburg (Gudensberg)

- Borken , with the Hessian lignite mining museum

- Bad Zwesten

- Homberg (Efze)

- Waldeck Castle and Edersee

- Garvensburg Castle in the Züschen district

- Fritzlar is located on the German Fairy Tale Route , which leads from Hanau via Fritzlar to Bremen.

Regular events

- Carnival, with Rose Monday procession

- Horse market (cattle market and folk festival), second weekend in July

- Hockey tournament with public celebration at the end of October

- Culture weeks in front of the cathedral, in August

Fritzlar in literature

The well-known behavior advisor Adolph Freiherr Knigge wrote his satire Reise nach Fritzlar in the summer of 1794 in 1795 .

Personalities

sons and daughters of the town

- Herbort von Fritzlar (around 1200), German-speaking poet of the Middle Ages

- Hermann von Fritzlar († after 1349), influential mystic

- Johann Hefentreger (* around 1497; † June 3, 1542 in Bad Wildungen), reformer of the county of Waldeck

- Jeremias Homberger (* 1529 - † October 5, 1595 in Znojmo), Lutheran theologian

- Kaspar Sturm (* around 1545; † 1628 in Gudensberg), Calvinist theologian and university professor in Marburg

- Hadrian Daude (born November 9, 1704, † June 12, 1755 in Würzburg), theologian and historian

- Stephan Josef Stephan (born February 29, 1772; † January 5, 1844 in Braunfels), Solms-Braunfels official and royal Prussian district administrator

- Stephan Behlen (born August 5, 1784; † February 7, 1847 in Aschaffenburg), forest scientist, professor, founder in 1825 of the journal Allgemeine Forst- und Jagdwirtschaft

- Joseph Rubino (born August 10 or 15, 1799; † April 10, 1864 in Marburg), ancient historian

- Conrad Hellwig (born October 7, 1824 in Haddamar, † June 25, 1889 ibid), farmer, mayor of Haddamar and member of the German Reichstag

- Winand Nick (born September 11, 1831, † December 18, 1910 in Hildesheim), cathedral music director, music teacher and composer

- Ludwig Keller (born May 28, 1849; † March 9, 1915 in Berlin), archivist and Freemason historian

- Theodor Haas (born May 20, 1859; † 1939), philologist, teacher and historian

- Paul Diederich (born January 18, 1882 - † August 2, 1965 in Fritzlar), long-time cathedral sexton, honorary citizen of the city of Fritzlar

- Wilhelm Naegel (born August 3, 1904, † May 24, 1956 in Hanover), politician (CDU), Member of the Bundestag , Chairman of the Economic Committee of the Bundestag

- Friedrich Krommes (born September 26, 1906; † March 4, 1971 in Kassel), church administration lawyer and managing director of the Bruderhilfe VVaG

- Maximilian Diederich (* May 12, 1909, † May 7, 1979 in Fritzlar), missionary doctor in southern Nigeria, chief physician at the Heilig-Geist-Hospital in Fritzlar

- Karl-Heinz Ernst (born January 18, 1942), politician (SPD) and member of the Hessian state parliament

- Reiner Schöne (born January 19, 1942), actor, singer, songwriter and author

- Elke Leonhard (born May 17, 1949 in Werkel), politician (SPD), Member of the Bundestag 1990–2005

- Jutta Meurers-Balke (born December 6, 1949), archaeologist and archaeobotanist

- Horst Wackerbarth (* 1950), photo artist

- Jürgen Störr (* 1954), artist and filmmaker

- Stephan Balkenhol (born February 10, 1957), artist, sculptor

- Michael Schreiber (born August 10, 1962), linguist

- Peter Piller (born January 5, 1968), artist

- Manuel J. Hartung (born September 16, 1981), writer

- Jörg Rohde (born March 19, 1984), actor

- Aljoscha Schmidt (born June 26, 1984), handball player

- Sarah Knappik (born October 5, 1986), model

- Marc Bluhm (born July 22, 1987), actor and voice actor

- Mario Neumann (* 1988). actor

- Christian Durstewitz (born May 11, 1989), singer and songwriter

- Philip Stein (* 1991), publisher and activist

Acting in Fritzlar without being born there

- Boniface (* around 673; † 754 or 755)

- Wigbert (* around 670 in Wessex; † 747 in Fritzlar), missionary companion of Bonifatius and first abbot of the Benedictine monastery Fritzlar

- Witta von Büraburg (* around 700; † after 760), 741–747 Bishop of Büraburg

- Felix von Fritzlar († around 790), missionary and martyr

- Burkhart von Ziegenhain († 1247), 1240–1247 provost of the Petristift, 1247 archbishop of Salzburg

- Otto von Ziegenhain (* 1304; † 1366 in Mainz), 1333–1366 provost of the Petristift

- Ignazio Fiorillo (* 1715 in Naples, † 1787 in Fritzlar), opera composer

- Bettina von Arnim (* 1785 in Frankfurt am Main, † 1859 in Berlin), writer, 1794–1797 pupil at the Fritzlar Ursuline School

- Oskar von Watter (* 1861 in Ludwigsburg; † 1939 in Berlin), lieutenant general, 1907–1909 department commander in Fritzlar, 1908 honorary citizen of the city of Fritzlar, revoked in the late 1980s

- Wilhelm Jestädt (* 1865 in Fulda; † 1926 ibid.), 1905–1926 dean of the Catholic deanery in Fritzlar

- Julius Höxter (* 1873 in Treysa, † 1944 in Richmond upon Thames, Surrey, England), educator and writer of the Jewish faith, 1887/88 pupil at the preparation institute in Fritzlar

- Gustav Kron (* 1878 in Wolfhagen; † 1942 in the Kulmhof extermination camp), last Jewish teacher and prayer leader of the Jewish community in Fritzlar

- Sr. Veronika Jüngst († 1962), Vincentian , from 1901 at the Hospital of the Holy Spirit in Fritzlar, 1951 honorary citizen of the city of Fritzlar

- Erich Tursch (* 1902 in Lischa, Sudetenland, † 1983 in Kassel), painter and art teacher, teacher at the König-Heinrich-Schule Fritzlar

- Sr. Angelika Kill OSU (* 1917; † 2003), 1961–1992 head of the Ursuline School, first nun to study in Marburg, honorary citizen of the city of Fritzlar

- Gottfried Schreiber (* 1918 in Liegnitz; † 2003 in Fritzlar), 1975–1987 President of the State Veterinary Association of Hesse

- Ludwig Vogel (* 1920 in Petersberg; † 2014 ibid), 1966–1991 Dean of the Catholic Dean's Office in Fritzlar and 1968–1991 City Pastor of Fritzlar, honorary citizen of the city of Fritzlar

- August Franke (* 1920; † 1997), District Administrator of the Fritzlar-Homberg District, District Administrator of the Schwalm-Eder District, Member of the State Parliament (SPD)

- Hermann Stahlberg (* 1920 in Leichlingen, † 2005 in Fritzlar) German politician (CDU) and soldier in the Bundeswehr

- Peter Lakotta (* 1933 in Hamburg, † 1991 in Kassel), painter and ceramist; Student / high school graduate of the Realgymnasium (later König-Heinrich-Schule) Fritzlar

- Martin Uppenbrink (* 1934 in Bielefeld, † 2008 in Berlin), first President of the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation; Student / high school graduate of the Realgymnasium (later König-Heinrich-Schule) Fritzlar

- Josef Klik (* 1935 in Kottiken; † 2020 in Petersberg), former athlete, German champion in shot put, discus throw and decathlon; Student / high school graduate of the Realgymnasium (later König-Heinrich-Schule) Fritzlar

- Burkhart Prinz (* 1939 in Gensungen; † 2014 ibid), handball player and trainer, youth national trainer of the German Handball Federation; Student / high school graduate of the König-Heinrich-Schule Fritzlar

- Ulrich Skubella (* 1941 in Gleiwitz), anesthesiologist at the Hospital of the Holy Spirit; Founder of the Fritzlar cultural and development associations, honorary citizen of the city of Fritzlar

- Klaus Ahlheim (* 1942 in Saarbrücken; † June 17, 2020), education professor; Student / high school graduate of the König-Heinrich-Schule Fritzlar

- Dirk Schmitz von Hülst (* 1943 in Magdeburg), sociology professor; Student / high school graduate of the König-Heinrich-Schule Fritzlar

- Gerd Loßdörfer (* 1943 in Nordhausen), doctor, former athlete, German champion in 1966 and vice European champion in 1966 in the 400-meter hurdles; Student / high school graduate of the König-Heinrich-Schule Fritzlar

- Günther Bott (* 1944 in Leslau on the Vistula), former judge at the Federal Labor Court; Student / high school graduate of the König-Heinrich-Schule Fritzlar

- Peter Barthelmey (* 1945 (in Minsk?); † 2019 in Marburg), student / high school graduate of the König-Heinrich-Schule Fritzlar, Bundesliga handball player and coach

- Jens Beutel (* 1946 in Lünen; † 2019), politician of the SPD, 1997–2011 Lord Mayor of Mainz; Student / high school graduate of the König-Heinrich-Schule Fritzlar

- Werner Bätzing (* 1949 in Kassel), professor of cultural geography; Student / high school graduate of the König-Heinrich-Schule Fritzlar

- Jochen Beyse (* 1949 in Bad Wildungen), writer; Student / high school graduate of the König-Heinrich-Schule Fritzlar

- Heiner Lürig (* 1954 in Hanover), musician, producer, composer, musical writer

literature

- Karl Alhard von Drach (ed.): The architectural and art monuments in the administrative district of Cassel. Volume 2: Fritzlar district. (Text and photo book). Elwert, Marburg, 1909.

- Friedrich Bleibaum : Fritzlar - portrait of a historical city. Magistrate of the City of Fritzlar, Fritzlar 1964.

- Werner Ide: From Adorf to Zwesten: Local history paperback for the Fritzlar-Homberg district. Bernecker, Melsungen 1972.

- Karl E. Demandt: Fritzlar in its heyday. Trautvetter & Fischer, Marburg, Witzenhausen 1974, ISBN 3-87822-051-0 . (Marburg row 5.)

- Real dictionary of Germanic antiquity. 2nd Edition. Volume 10. de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1998, ISBN 978-3-11-015102-2 , pp. 87-91.

- Fritzlar in the Middle Ages. Festschrift for the 1250th anniversary. Magistrate of the city of Fritzlar in connection with the Hessian State Office for Regional Studies Marburg, Fritzlar 1974, ISBN 3-921254-99-X .

- Günther Binding , Udo Mainzer, Anita Wiedenau: Small art history of the German half-timbered building. 2nd Edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1977, Fig. 66.

- Heinz Stoob (Ed.): City folder Fritzlar. German city atlas. Vol. 2, 4th part. Acta Collegii Historiae Urbanae Societatis Historicorum Internationalis. Series C. On behalf of the Board of Trustees for Comparative Urban History e. V. and with the support of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft ed. by Heinz Stoob, Wilfried Ehbrecht, Jürgen Lafrenz and Peter Johannek. Großerchen, Dortmund-Altenbeken 1979, 1993, ISBN 3-89115-041-5 .

- History Society Fritzlar: Lovable Fritzlar. Fritzlar 1999, ISBN 3-00-003991-0 .

- Clemens Lohmann: Fritzlar . In: The Benedictine monastery and nunnery in Hessen (Germania Benedictina 7 Hessen). Eos, St. Ottilien 2004, pp. 208-212.

- Rainer Humbach: Fritzlar Cathedral. With a documentation attachment by Burghard Preusler, Katharina Thiersch and Ulrich Knapp. Imhof, Petersberg 2005, ISBN 978-3-932526-53-4 .

- Sven Hilbert: Fritzlar in the age of the Reformation and confessionalization. (Sources and research on Hessian history 149), Hessian Historical Commission Darmstadt and Historical Commission for Hesse, Darmstadt & Marburg, 2006, ISBN 3-88443-303-2 .

- Jürgen Preuß: 70 years Fritzlar Airfield, 1938–2008: From Kampfgeschwader 54 to Combat Helicopter Regiment 36th Army Aviation School, Bückeburg 2008.

- Bettina Toson: Medieval hospitals in Hesse between Schwalm, Eder and Fulda. Hessian Historical Commission Darmstadt and Historical Commission for Hesse, Darmstadt and Marburg, 2012, ISBN 978-3-88443-319-5 .

Web links

- City website

- Fritzlar, municipality, Schwalm-Eder district. Historical local dictionary for Hessen. In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

- Fritzlar, Schwalm-Eder district. Historical local dictionary for Hessen. In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

- Georg Braun : Illustration of the city in Civitates orbis terrarum.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hessian State Statistical Office: Population status on December 31, 2019 (districts and urban districts as well as municipalities, population figures based on the 2011 census) ( help ).

- ↑ Ide, 1972, pp. 121-122

- ↑ The translation of the Latin inscription reads: In 1441 the jury Johannes Katzmann had this portrait of Saint Martin made

- ^ "Gray Tower" in Fritzlar. In: kudaba, the culture database

- ↑ Rau, Reinhold (Berb.): Letters of Boniface. Willibald's Life of Boniface. Darmstadt 1968, p. 494: "... in loco qui dicitur Gaesmere".

- ↑ The different manifestations of the place name in medieval documents are listed in the Historical Ortlexikon Hessen ( "Fritzlar, Schwalm-Eder-Kreis". Historical Ortlexikon für Hessen. In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).).

- ↑ Levison, Wilhelm (ed.): Scriptores Rerum Germanicorum in usum scolarum ex monumentis germaniae historicis, Vol. 57. Hannover / Leipzig 1905, p. 35: "... videlicet ecclesias Domino fabricavit; undam quippe in Friedeslare, quam in honore sancti Petri dedicavit ... "

- ↑ Franconian missionary work from 500, missionaries in Franconia: Willibrord, Bonifatius, Burkard, Lullus, Megingaud, ...

- ↑ M. Gockel, Fritzlar and the Reich . In: Fritzlar in the Middle Ages , pp. 89–120.

- ^ Ide, 1972, p. 107

- ^ Fritzlar, Portrait of a Historic City, Magistrat der Stadt Fritzlar, 1964, p. 3.

- ↑ Demandt, 1974, pp. 26-27

- ↑ Lovable Fritzlar, 1999, p. 13.

- ^ Herbert Pohl: Magic belief and fear of witches in the Electorate of Mainz. A contribution to the witch question in the 16th and early 17th centuries . Franz Steiner, Stuttgart, 1998, ISBN 3-515-07444-9 , p. 22.

- ↑ Witch Trials in Kurmainz Working Group , headed by Ludolf Pelizaeus: Witches Trials in Kurmainz, "punishment of the abominable magic of magic" , multimedia CD, series: Dieburger Kleine Schriften, edited by Archäologische und Volkskundliche Arbeitsgemeinschaft Dieburg eV - Verein für Stadt und Heimatgeschichtsforschung, 64823 Groß- Umstadt, 2004, General and Modern History. Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz.

- ↑ Paul Gerhard Lohmann: Evangelical Christians in Fritzlar , Books on Demand, Norderstedt, 2004, ISBN 3-8334-0730-1 , S. 97th

- ↑ StA Wü MRA 7770, fol. 13-25. Herbert Pohl: Magic belief and fear of witches in the Electorate of Mainz. A contribution to the witch question in the 16th and early 17th centuries . Franz Steiner, Stuttgart, 1998, ISBN 3-515-07444-9 , p. 26.

- ↑ Law on the reorganization of the districts Fritzlar-Homberg, Melsungen and Ziegenhain (GVBl. II 330-22) of September 28, 1973 . In: The Hessian Minister of the Interior (ed.): Law and Ordinance Gazette for the State of Hesse . 1973 No. 25 , p. 356 , § 16 ( online at the information system of the Hessian state parliament [PDF; 2,3 MB ]).

- ^ Federal Statistical Office (ed.): Historical municipality directory for the Federal Republic of Germany. Name, border and key number changes in municipalities, counties and administrative districts from May 27, 1970 to December 31, 1982 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart / Mainz 1983, ISBN 3-17-003263-1 , p. 392-393 .

- ↑ After abuse scandal: Order withdraws , HNA , June 30, 2010

- ↑ Guide of the Premonstratensian Order. Fritzar. Accessed April 2019 .

- ^ Regional Museum Fritzlar

- ↑ Named by the Wehrmacht leadership after General Oskar von Watter , who from 1907–1909 was the commander of the riding department of the 1st Kurhessian Field Artillery Regiment No. 11 stationed in Fritzlar and who in 1908 had become an honorary citizen of the city.

- ↑ Most of the former barracks buildings have since been demolished.

- ^ Jürgen Preuß, 70 years of Fritzlar airfield, 1938–2008 .

- ↑ Demandt, 1974, p. 29

- ^ Result of the municipal election on March 6, 2016. Hessian State Statistical Office, accessed in April 2016 .

- ^ Hessian State Statistical Office: Result of the municipal elections on March 27, 2011

- ^ Hessian State Statistical Office: Result of the municipal elections on March 26, 2006

- ↑ Spogat becomes Fritzlar's new mayor , HNA , accessed on January 30, 2012

- ^ Regional Museum Fritzlar

- ↑ After the destruction of the city by Konrad von Thuringia in 1232, a Gothic building was erected on a Romanesque cellar, which served as a chapter room and collegiate hall until 1540. Then it was used as a tithe barn. The baroque facade and the roof structure date from the 18th century. Since total renovation 1978-1980 it has been used as a community hall.

- ↑ The Gothic Curia was built around 1410 and was one of a total of 18 curiae, residential houses of the canons , in the monastery district around the cathedral. The roof, which was destroyed in the Seven Years' War, was restored in its original form with stepped gables in 1928 .

- ↑ Tomb of Elisabeth and Paul Diederich