Buraburg

| Buraburg | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Remains of the Büraburg |

||

| Creation time : | First mentioned in 742 | |

| Castle type : | Hilltop castle | |

| Conservation status: | Leftovers | |

| Construction: | Early medieval fortifications | |

| Place: | if you don't think | |

| Geographical location | 51 ° 7 '13.9 " N , 9 ° 14' 11" E | |

| Height: | 279 m above sea level NHN | |

|

|

||

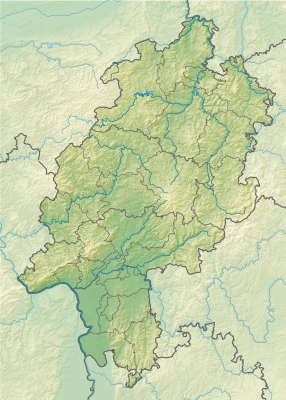

The Büraburg was a Franconian hilltop castle on the Büraberg above the Fritzlar district of Ungedanken in the Schwalm-Eder district , Hesse ( Germany ). Only remnants of the complex have survived today. On the former castle grounds, however, there is still one in the 6th – 7th Century church in the middle of a tree-lined cemetery. The church, from which the view falls over the Edertal to Fritzlar, is still the destination of annual processions and pilgrimages.

geography

The castle stood on the Büraberg ( 275 m above sea level ), the northeastern edge of the Hessenwald ( natural area 341.6, part of the Ostwaldecker Randsenken ), a mountain spur that slopes steeply on two sides to the valley of the Eder , which is above or east of the village of Ungedanken or 2.5 km southwest of Fritzlar protrudes into the Edertal. With the Eckerich opposite , the Büraberg at the exit of the Eder from the Wildunger Senkenland into the Fritzlar-Wabern Basin forms the so-called " Porta Hassiaca ".

A section of the Bonifatiusweg ("x12") runs over the summit of the Büraberg , which also leads through Fritzlar and Borken .

history

A large castle was built on the north-eastern flank of the Franconian Empire to protect the Eder area on the square, which has been populated for thousands of years (including the Upper Palaeolithic , Michelsberg culture , La Tène and Roman imperial times).

Around 680 a Frankish imperial castle was built with around 8 hectares of interior space, a mortar wall at least 1.50 m thick, several towers and three gates. Several pointed trenches were dug at the particularly endangered places. There was no outer bailey on the eastern part of the Bergsporn, this area was uninhabited in the early Middle Ages. Around 700 the fortifications were reinforced by new, thicker (approx. 1.80 m) walls. The gates were extended. So far, however, one can only speculate about the appearance and structure of the interior settlement as a whole (post structures, frame houses on stone beams or cellars, pit houses). The church of St. Brigida was built on the central summit plateau.

In 723, the Büraburg served St. Boniface as a base of operations and a military protective shield when he felled the Danube oak near Geismar , which is only a few kilometers away , probably on today's cathedral square in Fritzlar . He had a chapel built from the wood of the oak, which he consecrated to the apostle Peter . This wooden church was the nucleus of the Benedictine monastery Fritzlar founded by Bonifatius in 724 , the first abbot of which he appointed St. Wigbert . This convent was in a 1005 Säkularkanoniker- pin converted.

In 742 Bonifatius raised Büraburg together with Würzburg and Erfurt to dioceses. First bishop (741–755) became Boniface's companion Witta . As early as 755, however, the diocese, together with the diocese of Erfurt, which was also founded by Bonifatius, was incorporated into the diocese of Mainz by Lullus , as both hindered the further expansion of his diocese to the east and their task as missionary dioceses was considered to be completed. Afterwards, Büraburg was the archdeaconate (later moved to Fritzlar), the center of Mainz authority in northern Hesse and on the Eichsfeld . Witta continued to live in the Büraburg until his death in 760. Around 750 the walls were reinforced again due to the danger of further Saxon incursions , to a width of approx.

32 years after the founding of the diocese, the fortification in the border area between Franconia and Saxony was mentioned again in the Franconian imperial annals for the year 774 in connection with the Saxon Wars of Charlemagne . While Karl was in Italy, the Saxons invaded northern Hesse. The Fritzlar population escaped to the Büraburg and successfully resisted the siege, so that the invaders ultimately had to be content with the pillage and pillage of Fritzlar.

After the subjugation of the Saxons in 804, the Büraburg lost its military importance after losing its church political function. By the middle of the 9th century at the latest, the focus of settlement shifted to Fritzlar, and by the 13th century the Büraberg was no longer inhabited.

Plant and current condition

On the summit plateau of Bürabergs the Irish patron saint is Brigida consecrated chapel . The oldest surviving component is the choir arch wall, which could be dated to the period 543–668 or 558–667 (calibrated) using C-14 AMS analyzes ( ETH Zurich , 2002) of charcoal particles in the lime mortar. This would be the oldest church building east of the Limes in its origins .

There is no reason to doubt the accuracy of the C-14 analyzes, but it should be asked whether the wood samples taken from the masonry mortar of the choir arch wall and used for these analyzes did not come from wood that was only used for a second time in the manufacture of the Mortars were used. This interpretation is expressly contradicted by the conservator of the state preservation of monuments, referring to the condition and structure of the wood. According to the results of the excavation in Sondershausen, which is not far from the Büraburg, it cannot be ruled out that the St. Brigida Chapel was originally a sacral building with pagan references and was first introduced by the Anglo-Saxon missionaries (one should think of the above Boniface in Thuringia acting Willibrord was rededicated christian). The same is assumed for the two-aisled building excavated in Sondershausen on the edge of the Merovingian cemetery (D. Walter, see literature ).

The assumption that the Brigida patronage can be traced back to Irish-Scottish monks is now doubted, because it is so far first attested in a certificate of indulgence from the year 1289 and on the continent the oldest evidence of the veneration of the saints comes from the 8th century . Both of these factors suggest that the patronage changed in the course of the additions and renovations to the chapel, although the original one would be unknown.

The most recent excavations by the Hesse Archaeological Monument Preservation (2005) did not reveal any evidence of a pre-Carolingian building inside the chapel on the so-called "west tower". The masonry of the tower sits on the remains of a previous building, which in turn rests directly on the red sandstone and is dated to the time between the end of the 9th and the beginning of the 11th century through a skeleton find using a C-14 AMS analysis could.

The chapel forms the center of the Franconian fortifications , which existed at least from the end of the 7th to the middle of the 9th century and were built in a very elaborate and representative manner for the time , consisting of up to three deep trenches staggered one behind the other and a continuous wall ring with three gates consisted of lime-mortar red sandstone . In the course of several years of excavation campaigns by J. Vonderau from 1926 to 1931 and during the 1960s and 1970s, several expansion phases could be identified. According to an interpretation by N. Wand (1997), it comprised an interior area of approx. 8 hectares with evidently dense, regular buildings in various periods since prehistoric times and an unpaved "outer bailey" of about 4 hectares adjacent to the fortified area to the east. On this side, opposite to the main direction of defense, a number of postings and pit houses of unclear time and shape were found, which N. Wand interpreted as early medieval farm buildings. There was also a spring in this area , which was the main water supply for the fortification.

Excavations in the rear area of the lime mortar wall as well as extensive explorations in the so-called outer bailey by the University of Frankfurt am Main from 1999 to 2002 have on the one hand confirmed the Carolingian dating of the fourfold pointed moat in front of the fortification, but on the other hand also considerable doubts about older archaeological reconstructions and interpretations, especially the thesis developed by Walter Schlesinger since 1958 of an early medieval pre-urban development on the Büraberg. Dark humus-like layers behind the lime mortar wall turned out to be colluvial accumulation. Around the Ottonian period, the mortared wall areas could at least have been restored or even built. All pit findings recorded in the so-called outer bailey belong to prehistoric periods (mainly with ceramics from the Rössen and Michelsberg cultures) and exclude the existence of an early medieval settlement of traders and craftsmen, i.e. a quasi suburban area of the office castle in the early Middle Ages. Overall, the signs of a rather weak, temporary use of the entire complex in the Carolingian era predominate, which corresponds to a use as a refuge in the 8th century, which is also attested in the written sources. A current overall processing of the finds and findings from Büraberg by Th. Sonnemann (2010) led to the result that "archaeological evidence for a central location in the economic-economic sense or even with a pre-urban character (missing)".

The most remarkable findings that can still be seen today on the hilltop are brick cellar and cistern remains of a generally medieval era next to the church and in the area of the south-east gate the gate itself with post marks and hotplates of a casemate-like row building along the fortification walls.

One of the archaeologists of the Bürabberg, Norbert Wand , who died on September 30, 2004, is buried in the cemetery near the Brigida Chapel .

literature

- Jan Fornfeist: Mortar examinations on the fortification walls of the Büraburg near Fritzlar (Schwalm-Eder district) and selected objects from the 4th to 11th centuries , in: Fund reports from Hessen 48/49, 2008/2009, Bonn 2011, pp. 207-317 , ISSN 0071-9889 .

- Thorsten Sonnemann: The Büraburg and the Fritzlar-Wabern Basin in the early Middle Ages. Settlement archaeological investigations on the central location-environment problem. Studies on the Archeology of Europe 12, ISBN 3774936552 , Bonn 2010, 517 pp.

- Andreas Thiedmann: St. Brigida on the Büraberg near Fritzlar-Ungedanken - new insights into building history , in: Hessen Archeology 2005, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-8062-2053-7 , pp. 99-102

- Joachim Henning & Richard Macphail: The Carolingian Oppidum Büraburg: Archaeological and micromorphological studies on the function of an early medieval mountain fortification in northern Hesse , in: B. Hänsel (ed.), Parerga Praehistorica, Bonn 2004, pp. 221-251

- Katharina Thiersch: The St. Brigida Chapel on the Büraberg near Fritzlar-Ungedanken , in: Denkmalpflege & Kulturgeschichte , ed. State Office for Monument Preservation Hesse, issue 2/2003, pp. 22–26

- Vonderau, Joseph: The excavations at Büraberg near Fritzlar 1926/31. The established Franconian fortifications, as well as the basic lines of the oldest church buildings at the first Hessian bishop's seat in the middle of the fort . 22. Publications of the Fulda History Association, ed. by Prof. Dr. hc Joseph Vonderau , Fuldaer Actiendruckerei, Fulda 1934

- Walter, Diethard: Report Sondershausen: In the sign of the empire , in: Archeology in Germany 6/2006, p. 66 f.

- Wand, Norbert: The Büraberg near Fritzlar , Guide to North Hessian Prehistory and Early History, Issue 4, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Kassel (ed.), Kassel 1974

- Wall, Norbert: The office castle near Fritzlar - a Franconian imperial castle with a bishopric in Hesse , in: Early medieval castle building in Central and Eastern Europe, Nitra conference from October 7th - 10th, 1996 , ed. Joachim Henning and Alexander T. Ruttkay, Bonn 1998 (there further references)

- Werner, Matthias: Irish and Anglo-Saxons in Central Germany. On the pre-Bonifatian mission in Hesse and Thuringia , in: Heinz Löwe (Ed.): The Iren and Europe in the Early Middle Ages , Stuttgart 1982, pp. 239–329

Web links

- Entry by Thorsten Sonnemann about Büraburg in the scientific database " EBIDAT " of the European Castle Institute

Individual evidence

- ↑ Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde , 2nd edition, Volume 10, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York, 1998, ISBN 978-3-11-015102-2 (p. 89).

- ↑ Thorsten Sonnemann: The Büraburg and the Fritzlar-Wabern Basin in the early Middle Ages. Investigations on the central location-environment problem . 2010, p. 44-45 .

- ↑ Katharina Thiersch (2009): On the building history of the St. Brigida chapel on the Büraberg. State of the art - an interim report. Reprint from “Archive for Middle Rhine Church History” 61st year 2009, 15 pages.

- ↑ M. Werner, p. 252

- ↑ M. Werner, p. 257