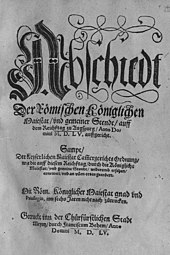

Augsburg Imperial and Religious Peace

The Augsburg Imperial and Religious Peace (often abbreviated to Augsburg Religious Peace ) is an imperial law of the Holy Roman Empire that permanently granted the supporters of the Confessio Augustana (a confessional text of the Lutheran imperial estates) their possessions and free exercise of religion. The law was passed on September 25, 1555 at the Reichstag in Augsburg between Ferdinand I , who represented his brother Emperor Charles V , and the imperial estates .

The Augsburg Recess is made up of two major parts: the rules that only the ratio of the confessions given (Peace of Augsburg, §§ 7-30), and those more general policy decisions holing ( Reich Enforcement Code , §§ 31-103).

With the Augsburg Peace Work, the basic conditions for a peaceful and lasting coexistence of Lutheranism and Catholicism in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation were established for the first time by imperial law. This included, on the one hand, an extensive realization of the parity of denominations through the principle of equality, on the other hand the implicit proclamation of a peace , because "in the ongoing division of religion a complemented tractation and action of peace in all things, religion, prophane and worldly matters, is not accepted" (§ 13 of the Reichs Farewell). In addition, the Augsburg Imperial and Religious Peace replaced the idea of a universal Christian empire, although the idea of a possible later reunification of the two denominations was not excluded. In general, the Augsburg Religious Peace is seen as the preliminary conclusion of the Reformation era in Germany, which was initiated by Martin Luther in 1517 .

After lengthy negotiations, an agreement was reached on the ius reformandi : Using the formula Cuius regio, eius religio (introduced later) , the Augsburg Religious Peace empowered the respective sovereign to determine the religion of his subjects; the latter, on the other hand, was granted the right to leave their country with the ius emigrandi . In addition to these simple and easily understandable basic regulations, however, on closer inspection there were also complicated special and exceptional regulations in the contract, which were not infrequently contradicting themselves and thus made religious peace a confusing and complicated contract. This resulted in numerous theological controversies in the period that followed, which reached their climax from the 1570s, especially in the wake of the increasing intensification of the conflict situation.

With regard to the long-term consequences of the Augsburg Religious Peace, it can be said that, on the one hand, it created legal clarity in some denominational and political issues, which heralded one of the longest periods of peace in the empire (from 1555 to 1618); On the other hand, however, some problems persisted subliminally, while others were only created anew through ambiguity, contradictions and complications. Together, these contributed to the increase in the denominational conflict potential, which, together with the latent political causes, would lead to the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War in 1618 .

prehistory

At the beginning of the 30s of the 16th century, the Reformation spread to many territories and imperial cities of the Holy Roman Empire. This raised the question of the legal position of Protestantism, whose teachings were officially considered heresy. In the eyes of many Catholics, the Roman-German Emperor had to oppose the spread of such "heresy". As a result of the Augsburg Diet of 1530 , the position of Protestantism under imperial law did not change, especially since the Confessio Augustana , a fundamental confession of Lutheranism , was not accepted by the emperor and the Catholic estates ( see also Confutatio Augustana ). In order to prevent a possible military recatholization of Protestant areas, the Protestant imperial estates then founded the Schmalkaldic League on February 27, 1531 . In the following years several religious talks took place in order to restore the unity of the church. When these failed - also because of political motives - Emperor Charles V decided to take military action against the federal government and defeated it in the Schmalkaldic War in 1547.

At the “armored” Augsburg Reichstag of 1548 (which was so called because Karl’s troops were still in the Reich) the emperor tried to use his military victory at Mühlberg politically: He forced the Protestant imperial estates to accept the Augsburg interim . The interim was supposed to regulate ecclesiastical relations until a general council would finally decide on the reintegration of Protestants into the Catholic Church. The largely pro-Catholic regulations issued by Karl were not, or only half-heartedly, enforced, apart from within the direct reach of imperial power in the south of the empire and in the imperial cities.

At the same time, the question arose as to who should succeed Charles V in the empire. This problem also contributed to the exacerbation of the existing conflict between the estates and the emperor: the emperor himself tried to implement his plan of the so-called Spanish succession , i.e. the transfer of the Roman-German imperial dignity to his son Philip II of Spain during his lifetime, in the empire. His brother Ferdinand I , who had already been elected Roman king in 1531, wanted to claim the imperial crown for himself and his descendants. The majority of the imperial estates were more inclined to Ferdinand's position on this matter. They feared that a successor from the Spanish line would be a first step towards a hereditary, Habsburg universal monarchy. In addition, this would also considerably limit their German liberty , their class freedoms.

In spite of his Protestant faith, Moritz von Sachsen supported the emperor in the Schmalkaldic War and received the Saxon electorate in 1547 . After that Moritz found himself in a difficult position: he was isolated within the Protestant camp, but was aware that the emperor's strong position could not last. Therefore he sat at the head of a rebellion against the Spanish succession. Because of this change of side, Moritz was called Judas of Meissen by the Catholics and the savior of the Reformation by the Protestants . The prince war that followed found Karl completely unprepared in 1552 and forced him to flee. The Emperor was not present at the negotiations that took place in Passau to settle the conflict. Ferdinand I acted as a mediator and negotiated with the princes.

In general, the longing for peace gradually arose in the empire after the numerous unrest and confessional wars of the Reformation. The Second Margrave War (1552–1555) followed immediately after the Prince's War , triggered by the territorial claims of Albrecht Alcibiades , the Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach. The military and political stalemate between Lutherans and Catholics diminished the hope of being able to further expand their own sphere of influence. This favored a tendency towards peace - both sides were ready to make concessions for a comprehensive peace settlement.

Ferdinand I, brother of the incumbent Emperor Charles V, had probably come to the insight through the Schmalkaldic War and the subsequent prince uprising that Protestantism could not be brought down by military means. He then convened a Diet in Passau in 1552 to negotiate the relationship between the two denominations with princes and estates of a generation that was now comparatively willing to compromise. The resulting Passau Treaty , the regulations of which were limited in time, was merely a religious-political “interim solution”, a “ceasefire”. The reason for this was Charles' refusal to sign a treaty that made permanent concessions to the Protestants. Nevertheless, the Passau Treaty was a step towards a lasting peace that was to be concluded in Augsburg three years later.

After the Passau Treaty, Charles V saw that his ambitious political goals in the empire had largely failed, and slowly began to resign. He moved to Brussels in 1553 and never returned to the empire. He placed imperial politics almost entirely in Ferdinand's hands.

The Diet of 1555

After the imperial estates had gathered in Augsburg, the Reichstag was opened on February 5 under the direction of Ferdinand I.

With his promise to settle the religious question in the Reich at the next Reichstag, Karl saw himself put on the defensive and tried to postpone it as long as possible. It was only after long pressure from the imperial estates that Emperor Charles V gave in in 1553. The emperor would have liked to have only issued a provisional settlement at this Reichstag, but the imperial estates pushed for a permanent solution. Under no circumstances did the Kaiser want to attend the Reichstag personally. From the emperor's letters it appears that he did this partly out of consideration for his personal salvation, but also for health reasons.

In the Reichstag proclamation, Karl and Ferdinand deliberately avoided any mention of the Passau Treaty. From their point of view, the main focus of the Reichstag was the comprehensive safeguarding of peace . This complex of topics was well prepared through previous consultations and could be concluded relatively quickly. The very difficult question of religion, on the other hand, should only be discussed after this complex of topics has been concluded, as the emperor and his brother feared that the imperial estates could not agree and that the entire diet would end without result. The imperial estates rejected such a sequence of negotiations and put religious peace as the first item on the agenda.

The concept of a political peace, which deliberately excluded religious differences and on which the Augsburg peace agreement was ultimately based, was based on a proposal by Moritz von Saxony during the Passau negotiations. This basic idea was seen as promising and as an ideal starting point for the solution of the religious question in the empire, since an early agreement on theological-dogmatic questions was very unrealistic. The conviction that was widespread in the empire that a reunification of denominations was a prerequisite for a comprehensive peace settlement was gradually replaced by the insight that a political solution was more important than the elimination of theological differences.

One of the main difficulties during the negotiations was that the legal recognition of the denominational division of the empire was incompatible with canon law . Cumbersome legal formulations were supposed to conceal this fact and make it easier for the Catholic (and especially the spiritual) imperial estates to accept peace.

The question of whether each person could freely choose their creed or whether this freedom of choice should only apply to the authorities was fiercely controversial and was one of the central issues. The Protestants in particular demanded exemption for at least certain groups of people (the imperial knights, imperial and rural towns). The agreement finally reached with the freedom of belief in the imperial cities and the ius emigrandi was an important basis for the entire religious peace. Medieval legal statutes against heresy were thus effectively repealed.

The toughest and longest negotiations, however, took place over the spiritual reservation . Unbridgeable theological, legal and political contradictions threatened to cause the negotiations to fail several times. The Protestants could not accept the spiritual reservation because they saw in it a one-sided advantage of the Catholic side. Ferdinand tried to get their approval through a secret subsidiary agreement - the Declaratio Ferdinandea . Ultimately, the spiritual reservation was only included in the farewell by virtue of Ferdinand's royal authority - the evangelical estates had not approved it. From this they later derived the consequence of not being bound by it. The Declaratio Ferdinandea, however, was not part of the treaty. The question of their validity remained open.

Shortly before the end of the negotiations, the emperor made it clear to Ferdinand that he was in no way prepared to share political responsibility for the compromise reached in Augsburg. Karl saw the loss of importance of the imperial office that a religious division of the empire brought with it. He therefore asked his brother to delay the farewell to the Reichstag and to wait for his personal appearance at the Reichstag. Ferdinand was happy that a workable consensus had been reached after difficult negotiations and did not comply with this request. In order not to jeopardize the Reichstag farewell, Ferdinand also hid his brother's threat to resign from the imperial estates.

The religious peace was part of the Reichstag's farewell on September 25, 1555. In addition to the actual religious peace, the farewell also contained changes to the court order and the enforcement order to enforce the peace. Lutherans have now also been admitted to the Chamber Court as assessors and judges.

Content and regulations

The basic idea of the Augsburg Imperial and Religious Peace was to completely exclude theological questions and to regulate the coexistence of Catholics and Lutherans under imperial law. In contrast to previous peace agreements, this regulation should not be a temporary measure, but apply until a possible reunification of the two major denominations in the empire. Because of the refusal of Emperor Charles V to accept religious peace in his home country, it was not valid in the Burgundian Empire .

The details of the Augsburg Imperial and Religious Peace are difficult to access legal text. Questions of interpretation therefore later put a heavy burden on the relationship between the denominations in the empire. The ideas on which the contract is based are very easy to grasp:

Expansion of the peace

The Augsburg Religious Peace guaranteed the coexistence of Catholics and Lutherans, while the existing religious problems were only regulated legally, not theologically. The framework for this was the state peace order that had existed since the Worms Reform Reichstag of 1495 , into which the Lutherans were now included. Lutheran and Catholic imperial estates were thus guaranteed their respective church system. Both denominations were in future under imperial protection. A war for religious reasons was henceforth considered a breach of the peace .

However, this only applied to the Catholic and imperial estates based on the Confessio Augustana . Other Protestant denominations such as the Anabaptists were expressly excluded from this regulation. It remained unclear whether the Reformed followers of Ulrich Zwingli or Johannes Calvin could invoke the regulations. Catholics and Lutherans denied this claim. The Reformed declared that they were also supporters of the Confessio Augustana, but were only able to actually enforce this at the Augsburg Diet of 1566 . The special status of the Jews , which had been clarified eleven years earlier at the Reichstag in Speyer , was not affected by religious peace.

Cuius regio, eius religio

The core regulation of the Augsburg Religious Peace was based on a no longer religious, but rather a political compromise formula to which both sides could agree: Whoever rules the country should determine the faith: cuius regio, eius religio ("whose country, whose religion") - one Formula that the Greifswald lawyer Joachim Stephani introduced around 1604, i.e. posthumously, for the ius reformandi so aptly that it has remained until today.

This ban on confession did not mean the religious freedom of the subjects or even religious tolerance, but the freedom of the princes to choose their religion. The subjects who did not want to convert were only granted the right to emigrate to a territory of their faith with the ius emigrandi (§ 24 of the Reichs Farewell ).

It was thus a victory for the territorial lords over the empire, the victory of princely liberty over central power, the victory of religious pluralism over the idea of a universal Christian empire. After 1555 the emperor no longer had any religious authority, Lutheranism and Catholicism were formally equal. The Lutheran classes had achieved exactly what they had been denied before the start of the Schmalkaldic War: the recognition of their Augsburg Confession, the Confessio Augustana.

Special regulations

After 1555 it actually looked as if the peaceful intention of the Augsburg Religious Peace had come true. The situation initially calmed down, which was also related to the political circumstances: Emperor Ferdinand I (who had taken his seat after the abdication of his brother Charles V) remained a "peace-loving old man who got along extremely well with most of the Protestant princes" , and it is even assumed that his successor Maximilian II had sympathy for Protestantism in his youth.

In the 1570s there was a gradual generation change in political actors. With Rudolf II a particularly anti-Protestant and less willing to compromise emperor entered the political stage. Now the confrontation between the two denominations flared up again. One was now always anxious to get one's own opinion through at all costs, and in doing so accepted an aggravation of the conflict situation. The theologians now discussed ambiguous and contradicting passages which, on closer inspection, resulted in the contract and which could be interpreted for the benefit of their own and the detriment of the opposing party. The reason for the existence of numerous ambiguities was probably that they were needed in order to be able to conclude a compromise contract at all. Initially this tactic worked, but from the 1570s it became clear that the ambiguities in the contract text would lead to further conflicts.

Two special regulations had particular potential for conflict: One of these exception regulations was a clause contained in the Augsburg Religious Peace, the Reservatum ecclesiasticum (Latin for “spiritual reservation”), which provided for an exception to the principle of ius reformandi for spiritual territories. Should a clerical territorial lord convert to Protestantism, he had to resign his office and give up his rule (his benefice ). As a result, nothing stood in the way of the election of a Catholic successor through the associated cathedral or collegiate chapter . Ultimately, the "spiritual reservation" was aimed at preventing the secularization of spiritual principalities.

The majority of the Lutheran classes disagreed with this, they saw the “spiritual reservation” as a clear disadvantage. The clause was probably only tolerated by them because the emperor, in an additional treaty, the Declaratio Ferdinandea , granted indigenous evangelical knights, imperial cities, nobles and communities in spiritual areas freedom of religion. However, since such additional declarations were not allowed under Section 28 of the Augsburg Religious Peace and the Declaratio was not included in the official Reichstag pass, Catholics later often doubted its truthfulness. The majority of Protestants, on the other hand, saw the “spiritual reservation” as not binding.

Another point of contention was the Imperial City Article. Almost all imperial cities had opened up to the Reformation, the population was Protestant, but in some cities there were small Catholic minorities. The imperial cities did not want to accept that the minority could use half of the churches or hold half of the city offices. The visible practice of the Catholic religion (for example with processions) was seen as a political provocation.

Likewise, the position of the Calvinists under imperial law remained unclear; the Augsburg Religious Peace was expressly only valid for the followers of the Confessio Augustana.

Despite all these areas of conflict, the Augsburg Religious Peace, together with the general peace treaty agreed at the same time (Section 16), ensured an internal peace for the empire and prevented the outbreak of a major war for over 60 years. This period of peace is one of the longest in European history. It was not until the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War in 1618 that the differences emerged again and all the more violently.

Extract from the Augsburg Imperial and Religious Peace of September 25, 1555

- According to this, set, order, want and command that no one, of whatever dignity, class or character, should feud, war, capture, overrun, besiege, […], the other, but rather everyone with rights Friendship and Christian love should be opposed and the Imperial Majesty and We (the Roman King Ferdinand, who led the negotiations for his brother Charles V) should oppose all classes, and in turn the classes Imperial Majesty and Us, one class the other, with this one the subsequent religious construction of the established peace should be left in all pieces. "(§ 14 - Peace formula)

- “And so that such peace, even in spite of the religious division, as the necessity of the Holy Empire of the German Nation demands, the more constant between the Roman Imperial Majesty, Us, as well as the electors, princes, and estates would like to be established and maintained, the Imperial Majesty should , We, as well as the electors, princes and estates do not have any status of the empire because of the Augsburg denomination and its teaching, religion and belief in a violent manner, damage, rape or in any other way against knowledge, conscience and will of this Augsburg denomination, faith , Church customs, orders and ceremonies that they have established or will establish, force something in their principalities, countries and rulers or make it difficult or despise by mandate, but this religion, their lying and moving belongings, land, people, rulers, authorities , Glories and righteousness calm and peaceful h, and the disputed religion should not be brought to a unanimous, Christian understanding and comparison other than by Christian, friendly and peaceful means and ways. "(§ 15 - religious formula)

- "[...] Where an archbishop, bishop, prelate or another clerical class would resign from our old religion, that same archbishopric, diocese, prelature and other benificia, with all the fruit and income, if he had from it, soon without some Resignation and delay, but without prejudice to his honor, leave, even the capitals, and to whom it is part of common rights or the churches and conventions to see a person related to the old religion permitted to elect and regulate a person, including the spiritual Capitals and other churches at the churches and foundations, elections, presentations, confirmations, old traditions, justice and goods, lying down and driving, should be left unhindered and peaceful, but future Christian, friendly and finite comparison of religion is incomprehensible. "( § 18 - Spiritual reservation, Reservatum ecclesiasticum )

literature

Primary literature

- Rosemarie Aulinger, Erwein Eltz, Ursula Machoczek (eds.): German Reichstag files: The Reichstag in Augsburg 1555: XX. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag 2009, ISBN 978-3-486-58737-1 .

- Christian August Salig : Complete history of the Augsburg Conference and the same apology. Hall 1730 ( full text with excerpts from sources ).

Secondary literature

- Thomas Brockmann: Augsburg religious peace . In: Encyclopedia of Modern Times . J. B. Metzler , Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-476-01935-7 , Sp. 848-850 .

- Axel Gotthard : The Augsburg Religious Peace . Aschendorff, Münster 2004, ISBN 3-402-03815-3 .

- Axel Gotthard: From the Schmalkaldic War to the Augsburg Religious Peace: The implementation of the Reformation. In: Zeitverlag Gerd Bucerius (ed.): DIE ZEIT World and cultural history in 20 volumes. Volume 08, pp. 197-203.

- Carl A. Hoffmann u. a. (Ed.): When peace was possible. 450 years of religious peace in Augsburg . Accompanying volume for the exhibition in the Maximilian Museum Augsburg (June 16 - October 16, 2005). Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2005, ISBN 3-7954-1748-1 .

- Karl-Hermann Kästner : Augsburg religious peace . In: Albrecht Cordes , Heiner Lück , Dieter Werkmüller u. a. (Ed.): Concise dictionary on German legal history . 2nd Edition. tape I . Erich Schmid, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-503-07912-4 , Sp. 360–362 (Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand as philological advisor; Editing: Falk Hess and Andreas Karg; completely revised and expanded edition).

- Thomas Kaufmann : History of the Reformation. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-458-71024-0 .

- Harm Klueting : The Denominational Age . Ulmer, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-8001-2611-7 .

- Wolfgang Wüst , Georg Kreuzer, Nicola Schümann (eds.): The Augsburg Religious Peace 1555. An epochal event and its regional roots (= Journal of the Historical Association for Swabia. 98). Augsburg 2005, ISBN 3-89639-507-6 .

- Wolfgang Wüst: The Augsburg Religious Peace. Its reception in the territories of the empire. In: Hostels of Christianity. Yearbook for German Church History. Special volume 11, Leipzig 2006, pp. 147–163.

- Heinz Schilling , Heribert Smolinsky (eds.): The Augsburg Religious Peace 1555 . Scientific symposium on the occasion of the 450th anniversary of the peace treaty, Augsburg September 21-25, 2005. Aschendorff, Münster 2007, ISBN 978-3-402-11575-6 .

Web links

- Farewell to the Reich as a facsimile

- The Augsburg Reichs Farewell ("Augsburger Religionsfrieden") in full text, Internet portal "Westphalian History"

- Augsburg Imperial and Religious Peace in the Augsburg Wiki

- Gerhard Rampp: How peaceful was the religious peace in Augsburg? ( MIZ materials and information currently, issue 2-2005)

- Josef Asselmann, chronicler: Opening of the Reichstag in Augsburg (February 5, 1555)

- Augsburg Reichs Farewell of 1555 - digitized version that can be flipped through in the culture portal bavarikon

Remarks

- ^ Gerhard Ruhbach: Augsburg Religious Peace . In: Helmut Burkhardt, Uwe Swarat (ed.): Evangelical Lexicon for Theology and Congregation . tape 1 . R. Brockhaus Verlag, Wuppertal 1992, ISBN 3-417-24641-5 , p. 157 .

- ↑ a b The Great Ploetz. The Encyclopedia of World History, 35th, completely revised edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-525-32008-2 , p. 888 f.

- ^ Georg Schmidt: The Thirty Years' War. Beck, Munich 2003, p. 17.

- ^ Helmut Neuhaus: The Augsburg religious peace and the consequences: Empire and Reformation. In: Zeitverlag Gerd Bucerius (ed.): DIE ZEIT World and cultural history in 20 volumes. Volume 8, p. 214: "With it, under imperial law, the coexistence of both denominations [...] was permanently regulated [...]"

- ^ The Augsburger Reichs Farewell ("Augsburger Religionsfrieden") in full text. Retrieved March 7, 2018 .

- ↑ Axel Gotthard: From the Schmalkaldic War to the Augsburg Religious Peace: The implementation of the Reformation. In: Zeitverlag Gerd Bucerius (ed.): DIE ZEIT World and cultural history in 20 volumes. Volume 8, p. 203: "[...] the utopia of a reunification of the denominations was not disclosed, but was put aside for the moment."

- ^ Johannes Arndt: The Thirty Years War 1618-1648. Reclam Sachbuch, Stuttgart 2009, p. 30: "The Augsburg Religious Peace concluded the era of the Reformation, [...]."

- ↑ a b Axel Gotthard: From the Schmalkaldic War to the Augsburg Religious Peace: The implementation of the Reformation. In: Zeitverlag Gerd Bucerius (ed.): DIE ZEIT World and cultural history in 20 volumes. Volume 8, p. 203: “Religious peace is a very difficult text, many difficult questions of interpretation later strained the relationship between the denominations. [...] The basic ideas of religious peace are, as I said, simple and clear. The devil was in the details. But only later generations should painfully experience that. "

- ^ Johannes Arndt: The Thirty Years War 1618-1648. Reclam Sachbuch, Stuttgart 2009, p. 30: “[…] by solving certain political and denominational problems. Other problems persisted and contributed to the outbreak and course of the Thirty Years' War. "

- ↑ Axel Gotthard: From the Schmalkaldic War to the Augsburg Religious Peace: The implementation of the Reformation. In: Zeitverlag Gerd Bucerius (ed.): DIE ZEIT World and cultural history in 20 volumes. Volume 8, p. 198: "[...] should be at a reform council until the denominational dispute is finally settled [...]"

- ↑ Olaf Mörke: The Reformation: Requirements and Implementation , p. 61.

- ↑ Axel Gotthard: From the Schmalkaldic War to the Augsburg Religious Peace: The implementation of the Reformation. In: Zeitverlag Gerd Bucerius (ed.): DIE ZEIT World and cultural history in 20 volumes. Volume 8, p. 200.

- ↑ Axel Gotthard: From the Schmalkaldic War to the Augsburg Religious Peace: The implementation of the Reformation. In: Zeitverlag Gerd Bucerius (ed.): DIE ZEIT World and cultural history in 20 volumes. Volume 8, p. 200.

- ^ Josef Asselmann, chronicler: Opening of the Reichstag in Augsburg (February 5, 1555)

- ↑ Axel Gotthard: From the Schmalkaldic War to the Augsburg Religious Peace: The implementation of the Reformation. In: Zeitverlag Gerd Bucerius (ed.): DIE ZEIT World and cultural history in 20 volumes. Volume 8, p. 200 f .: "The prevailing conviction that every peace presupposed the previous reunification of the denominations gave way to the insight that now the time for an 'external', 'political' peace has come."

- ^ Georg Schmidt: The Thirty Years' War. Munich, Beck 2003, p. 17.

- ↑ a b Axel Gotthard: Renewal of the old. Catholic Reform in the Holy Roman Empire. In: Zeitverlag Gerd Bucerius (ed.): DIE ZEIT World and cultural history in 20 volumes. Volume 8, p. 336 f .: "The Protestant minority had already not approved this exception provision at the Diet of 1555, so since then they have maintained that this clause is none of their business."

- ^ A b Johannes Arndt: The Thirty Years War 1618–1648. Reclam non-fiction book, Stuttgart 2009, p. 32.

- ↑ Peter Blickle : The Reformation in the Empire. 3rd comprehensively revised and expanded edition. Ulmer, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8252-1181-9 ( UTB for science - university paperbacks - history 1181).

- ↑ a b Helga Schnabel-Schüle : The Reformation 1495–1555 . Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017048-6 .

- ^ Harm Klueting : The denominational age. Ulmer, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-8001-2611-7 , p. 141.

- ↑ The Augsburg Reichs Farewell ("Augsburger Religionsfrieden") in full text: "§ 24. But where ours, including the electors, princes and estates are subject to the old religion or the Augsburg Confession, because of their religion from ours, including the electors, princes and estates of the H. Reich Lands, princes, cities or towns with their wives and children to move to other places and want to settle down, such departure and arrival, including the sale of their belongings and goods for a fair, cheap payment of serfdom, and Post-tax, as it has been customary, brought and kept in every place of old age, unhindered and approved by the male, and unpaid for their honors and duties. But the superiority of their righteousness and tradition of the serfs, whether they count single or not, should not be broken off or dazed by this. "

- ^ Axel Gotthard: Renewal of the old. Catholic Reform in the Holy Roman Empire. In: Zeitverlag Gerd Bucerius (ed.): DIE ZEIT World and cultural history in 20 volumes. Volume 8, p. 332.

- ↑ Compare Michael Kotulla: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934). Berlin / Heidelberg 2008, p. 67 ( online ): "It was now more and more about demarcation, about the final victory of the only true, own denomination, about interest egoism, but not about compensation."

- ^ Axel Gotthard: Renewal of the old. Catholic Reform in the Holy Roman Empire. In: Zeitverlag Gerd Bucerius (ed.): DIE ZEIT World and cultural history in 20 volumes. Volume 8, p. 333 f .: “So one finally pulled oneself together without agreeing on the last point - where there was no other way, at the expense of clarity and truth. For a while it seemed like this game would pay off, but in the long run the disadvantages of the method chosen at the time outweighed it. "

- ↑ Axel Gotthard: Schlaglicht 1555: the first religious peace. In: bpb - Federal Agency for Political Education. January 8, 2017, accessed June 26, 2019 .