Konrad I. (Eastern France)

Konrad I (around 881 ; † December 23, 918 in Weilburg ; buried in Fulda ) was Duke of Franconia from 906 and King of Eastern Franconia from 911 to 918 .

Nobility feuds between the powerful aristocratic families for supremacy in the individual tribal areas of the East Franconian Empire, the repeated invasions of Hungary and the weakness of the Carolingian kingdom led to the establishment of regional middle powers, the later duchies . During this time the rise of Konrad fell, who himself was a representative of these rising regions and at the same time was involved in the regiment of the East Franconian Carolingian Ludwig the child . As king, Konrad tried to oppose the threatened dissolution of the imperial association and to exercise rule again throughout the empire. His seven-year reign is therefore mainly characterized by the conflicts with the East Franconian duces of the individual sub-empires and by the Hungarian invasions. Konrad's rule formed the transition from the Carolingians to the Ottonians , as he did not succeed in founding a new royal dynasty. He continued the rule of the Carolingians.

His time is one of the poorest sources in the entire Middle Ages. While the Ottonian historical works written decades later still attribute positive characteristics to Konrad, in research he is often considered to have failed with his entire reign. For a long time, Konrad's election was seen as the beginning of German history. Only recently did the view prevail that the German Reich did not come into being in one act, but in a long process. Nevertheless, Konrad is seen as an important player in this development.

Life until the assumption of power

Origin and family

Konrad came from the Frankish family of the Konradines, which can be verified since the middle of the 9th century . It had risen through loyal royal service under Emperor Arnulf and had extensive manorial estates on the Middle Rhine and in Main Franconia . The Conradin core landscape of the Rhine - Lahn - Main area was supplemented by counties in Wetterau , Lahn and Niddagau as well as house pens in Limburg , Weilburg and Wetzlar , the peripheral zones of what would later become Upper Hesse .

Konrad's father, Konrad the Elder , who was born around 855 , was count in Hessengau , Wormsfeld and Gozfeld in Main Franconia . He married Glismut , an illegitimate daughter of the Emperor Arnulf of Carinthia . Konrad the Elder had three brothers: Gebhard , who was count in the Rheingau and Wetterau, Eberhard, count of the Oberlahngau, and Rudolf . Rudolf was Bishop of Würzburg from 892 , Gebhard from 903 also Duke of Lorraine.

The weakness of the royal rule under the last Carolingian ruler in Eastern Franconia, Ludwig the Child , and the lack of clarity of the balance of power led to far-reaching feuds, which were also interrupted by devastating incursions by the Hungarians. During these incursions, the uncles of the later King Konrad, Rudolf and Gebhard (908 and 910), lost their lives.

The rise of the Konradines in Eastern Franconia and their territorial expansion did not go without resistance from the other greats. As early as 897 , a long feud broke out in Franconia between the two leading aristocratic families, the Conradinians and the Babenbergers , which concerned the delimitation of the spheres of power in this part of the empire. Eberhard, Konrad's uncle, was killed in the fighting in 902. In 906, Adalbert from Babenberg used the Konradine power, weakened by a campaign in Lorraine, for a campaign during which Konrad's father was killed in action against Adalbert in the battle of Fritzlar . The imperial government supported the Conradines in the feud, however, and turned the tide. At the instigation of the East Frankish king, Adalbert was captured and beheaded. The feud, which ended in the same year in favor of the Konradines, led to considerable shifts in the balance of power: The Konradines gained the undisputed supremacy in all of Franconia.

The Conradin dominance at the court and the outcome of the Babenberg feud also cost the Liudolfingers , who were related to the inferior Babenbergs, the closeness to the king that they still had in Arnulf's time. But this also meant that the influence of the king in Saxony and Thuringia waned, and with it that of the Conradines. Not a single time can the very young King Ludwig stay in Saxony.

In their attempt to usurp leadership positions in Lorraine as well, the Konradines also encountered resistance from the Matfriede , one of the most powerful noble families in this area. When the Matfriede occupied the Abbeys of the Conradines in Lorraine , Konrad successfully took to the field against them in 906.

Konrad had three brothers, Eberhard von Franken , Burchard and Otto , who was about four years his junior . In 904 and 910 Konrad is attested as a (lay) abbot in Kaiserswerth . However, in a document in 910 it is referred to as dux . The title could indicate a ducal dignity or serve to highlight the Konradin, who was unrivaled in the empire at that time and who had risen to the position of head of the Konradin family through the death of his uncles and father. Since 909 it was only the Conradines among the secular lords who intervened in the documents of Ludwig the child .

The king's successor

Lorraine , the former heartland of the Carolingians, was under its own rule with Ludwig's half-brother Zwentibold . This enabled Franconia to become the core of an increasingly independent Eastern Empire under the rulers Arnulf and Ludwig the Child. Here the Konradines formed by far the strongest power, especially after the Babenbergs were excluded. When the heirless Karolinger Ludwig from East Franconia died in September 911, they were well prepared for the expected succession battles.

The Conradines had not only expanded their position militarily and in the context of the prestige struggles among the greats of the empire, but also at the level of legitimation. The relationship with the Carolingians played a not insignificant role. Konrad was well aware of this. Since 908 he has appeared as an intervener in almost every second document that has been handed down. He is mostly emphasized as a blood relative, consanguineus , of the king, Ludwig in turn calls Konrad his nepos . Konrad thus occupied the position of a secundus a rege early on , a second after the king. The transfer of rule to Konrad was by no means surprising, as the later portrayal of Widukind suggests, who portrays Konrad as a candidate for embarrassment.

Other factors also favored Konrad's choice. The only living Carolingian, King Karl III of West Franconia . ("The simple-minded"), was not a debatable candidate for the noble families of the Eastern Empire. His political weakness and his military unsuccessfulness spoke against him. The Carolingians were no longer able to hold together the divergent parts of the empire, only the great Lorraine inclined towards Charles.

The heads of the noble families of the Eastern Empire also ruled out for the royal succession. Otto the illustrious , the head of the Saxon Liudolfinger , appeared as an intervener in only two royal documents and was also far removed from the royal court. Luitpold from the noble family of the Bavarian Luitpoldinger was also referred to by Ludwig in his documents as nepos or even more frequently as propinquus noster (our relative). However, his proximity to the royal court was limited to his stays in Bavaria. What was decisive, however, was that Luitpold fell during a Hungarian campaign in 907 and that his son Arnulf was still too young to succeed the king.

Konrad's rise to the kingdom of East Franconia was largely based on the position of power that his ancestors had fought for in the empire. After the death of his father, as evidenced by the interventions in royal documents, he had risen to become the dominant secular advisor at the royal court of Ludwig the child. The excellent contacts with the other members of the regent circle, such as Archbishop Hatto of Mainz or the Bishops Adalbero of Augsburg and Solomon of Constance , also contributed to the outstanding position of the Konradines .

After Ludwig the child died on September 24, 911, a good six weeks later, on November 10, in Forchheim in Franconia, Saxony , Alemanni and Bavaria elected Franconia Konrad as king. By opting for Forchheim, the greats and the new king embraced the East Franconian imperial tradition. Probably the most important advocate of this election was Archbishop Hatto of Mainz, the most important clerical officer in the East Franconian Empire. Solomon of Constance, who had lamented the weakness of the child king Ludwig, should have been one of Konrad's supporters. However, the Lorraine people were not involved , who recognized the West Frankish King Charles the Simple as their master.

The East Frankish king

The starting point

Konrad came into power under extremely difficult conditions. For decades, the empire had suffered from raids by external enemies. Although the danger from the Normans had subsided towards the end of the 9th century, and the Saracens were no longer a threat, the Hungarians threatened the empire from then on. Unlike the Normans, the Hungarians did not go across the sea or rivers, which would have made preventive measures possible, but across the open country. In addition, they were much faster in their movements and not tied to predetermined routes. After the catastrophic defeat of the Bavarians under Luitpold's leadership in the Battle of Pressburg on July 4, 907, the Hungarians moved to Alemannia in 909, which may have prompted King Ludwig to avoid this region after Saxony and Thuringia and henceforth exclusively in To stop Francs. In 910 an imperial army under the personal leadership of Ludwig the Child was defeated on the Lechfeld near Augsburg . When Ludwig's rule ended with his death in 911, the empire was almost defenseless at the mercy of the Hungarian raids.

In the interior of the empire, the royal central power had lost its reputation through disputes over the throne within the ruling dynasty of the Carolingians and through underage and weak kings. Five kings between 876 and 911 could not maintain an effective royal power. Your orders no longer penetrated all parts of the empire. The Hungarian invasions intensified the disintegration. Under Luitpold's successor, Arnulf , who was primarily concerned with consolidating his position in Bavaria, relations with the Reich had almost come to a standstill. This process of alienation at the royal court was intensified by the promotion of Conradin dominance and the lack of cooperation and integration of the regional rulers. In the individual tribal areas, powerful aristocratic families fought for supremacy or the regents tried to secure and secure their position. The Conradinians also managed to narrow the court down to Franconia. This ultimately led to uprisings in Alemannia as well. The Bavarians pursued a separation course, the Liudolfingers in Saxony had moved far away from the court, Lorraine joined West Franconia.

Carolingian continuity

Konrad tried to continue the Carolingian rule and to place his rule in the tradition of Carolingian kingship. This was particularly evident in the royal documents and in the organization of the court orchestra, including the chancellery belonging to this institution. The notaries were taken over from the chancellery of Ludwig the child. At the head of the chancellery and chapel was the Bishop of Constance, Salomon , who had already performed these tasks during the time of Ludwig. In his documents Konrad maintained the memory ( memoria ) of the Carolingians. In his very first document he recorded his predecessors in memory. Konrad has confirmed her donations and awards many times. In his notarization practice, the monasteries and dioceses that his predecessor had already considered were often privileged. As a founder , he almost exclusively addressed groups of people who had already appointed his predecessors in the East Franconian royal office as trustees and beneficiaries . In Eichstätt and St. Gallen, Konrad tied the foundations of Ludwig the Child and Charles III. on. Numerous foundation documents from Carolingian rulers have also come down to us for Fulda, Lorsch and Regensburg. The foundations primarily served the salvation of soul and memory. The continuity is also emphasized in the legitimizing emblems. The seal of his predecessor, which depicts the ruler with a shield, flag lance and diadem, ready to fight or as an army commander intended by God with victory, was also adopted by Konrad. In addition, he allied himself in the Carolingian tradition with the church in order to fight the rising princely middle powers.

Assumption of power

At the beginning of his reign, Konrad probably received the anointing from Archbishop Hatto of Mainz, which had already been an important element of legitimation for the Carolingians. After the documents and activities of the first year of reign, Konrad came to power from a relatively stable position. The high level of acceptance of the interveners in the first two years of government shows both a broad acceptance of his rule and the participation of the big players in the government.

As one of his first actions, Konrad carried out a tour of Swabia and Franconia to the borders of Bavaria and Lorraine immediately after his election . As the first king since Ludwig the German and Arnulf of Carinthia , he re-entered Saxony. With the ritual, Konrad intended to exercise royal rule again in all areas of the empire. One of his first trips took him to southern Swabia to see Bishop Solomon of Constance. Konrad celebrated the first Christmas party in Constance . On the second day he and Solomon went to visit the St. Gallen monastery . There he spent three carefree days and he was accepted into the prayer fraternity of the monastery. The entry in the St. Gallen fraternity book served to secure the memoria , since Konrad would also find entry into the heavenly book through the intercession of the monks, in which God wrote down the names of the righteous. In return, Konrad made rich donations for the monastery: silver for each brother, three days off school for the children to play, equipping the Gallus basilica with valuable blankets and confirmation of the monastery immunity. The course of the visit, the portrayal of Konrad in the sources as primus inter pares , the promise of help in prayer, and the portrayal of Bishop Solomon as a match of the king suggest the conclusion of an amicitia . It was a system of sworn friendship alliances as a means of rule.

The loss of Lorraine

The death of the Conradin Duke Gebhard in 910 had already weakened the position of the Conradins in this region. In July or August 911 large parts of the Lorraine nobility had turned away from Ludwig the Child and the Conradinians. In January 912, King Charles III appeared. in Lorraine and even penetrated as far as Alsace to assert the West Franconian property claim. He had documents issued, which also concerned Conradinian property. At the beginning of November, the Lorraine people recognized Charles the Simple as King.

To defend his claim to rule over Lorraine and the possessions and rights of his family there, Conrad I led three campaigns in 912 and 913. At first he succeeded in pushing back the West Franconia, but in the same year the Lorraine greats invaded Alsace again and burned Strasbourg down. Two more campaigns were unsuccessful. Although the regional balance of power was hardly determined by Charles, Lorraine had been deprived of Konrad's influence since 913. This meant a loss of prestige: Lorraine was regarded as the traditional cultural and economic center of the former Greater Franconian Empire, as the imperial city of Aachen was located here. However, the means of power of royalty and important family positions in the West were also lost. The loss of the Conradin Abbey of St. Maximin in Trier must have been felt as particularly painful.

Resource and personnel policy

As a result of the change of dynasty, the regional and local ruling classes, which included counts, bishops, abbots, the lords of the castle and the royal vassals , had to realign their relations with the king. Of the five church provinces of the East Franconian Empire, only the seats of Mainz , Trier and Bremen became vacant and could be filled again. The church provinces of Trier and Cologne joined 911 Lorraine. In May 913 Heriger succeeded the late Archbishop Hatto in Mainz . In Bremen, after the death of Archbishops Hoger in 916 and Reginward in 918 , Konrad did not appoint Provost Leidgard, who was elected by the cathedral chapter, but his chaplain Unni . In 912 he appointed the Salzburg Archbishop Pilgrim I to be Archkapellan.

Archbishop Radbod von Trier became Arch Chancellor of West Franconia in the summer of 913. When he died on March 30, 915, Konrad had no way of influencing the choice of his successor. The new Archbishop Ruotger von Trier remained in the West Franconian Reich Association. Konrad's influence on the occupation of dioceses is completely unknown. In the dispute over sovereign rights between bishops and counts, Bishop Einhard von Speyer was slain on March 12, 913 in Strasbourg . The Synod of Hohenaltheim commissioned Bishop Richgowo of Worms in 916 to investigate the murder . The outcome of the proceedings is unknown.

The dioceses could almost completely evade Konrad's control, and so the king tried to regain control as imperial abbeys of at least the larger Carolingian royal abbeys, which were often under the influence of episcopal commendatar abbeys or lay counts . The Abbey Murbach confirmed Konrad suffrage, immunity and security of tenure. He probably hoped for support for his politics from the monasteries, which he considered far more often than the dioceses with 23 documents. Konrad's special favor was Lorsch , who received five documents, as well as the diocese of Würzburg and the monasteries of Sankt Emmeram and Fulda , for each of which four documents have survived. Konrad visited Lorsch, the Saxon Corvey , the Franconian-Thuringian and Hessian monasteries Fulda and Hersfeld and the Swabian St. Gallen. He confirmed to these monasteries the old privileges of immunity and free election of abbots. He also sponsored them in part with new assignments. Konrad initially stayed in St. Gallen (Christmas 911), then followed Fulda on April 12, 912, Corvey on February 3, 913, Lorsch on June 22, 913 and Hersfeld on June 24, 918. The imperial abbeys should be reinforced again for servitium regis (royal service). The gas Tung of the royal court in transit, the human and material services in the event of war and the political tasks of the Abbot were the most important tasks of the Kingdom ministry. However, the amount of these burdens is unclear due to a lack of sources.

Hungarian invasions

Konrad remained inactive towards the Hungarians, who invaded his empire at least four times between 912 and 917. The reason is unknown, in any case the regional leaders were on their own. Nevertheless, they were able to achieve success: According to the sources, only one Hungarian invasion led to defeat. In 913 they were initially repulsed by the Alemanni under Count Palatine Erchanger and Count Odalrich. Duke Arnulf then almost completely destroyed an army on the Inn . The defeat in 913 went down in the collective memory of Hungarians and was often associated with other defeats and losses in Hungarian chronicles.

A victory over an external enemy could have considerably strengthened Konrad's reputation in a society that was shaped by the warrior nobility and their values such as honor and fame. After the loss of Lorraine and the evasion of the Hungarians, however, the royal rule began to rapidly lose authority as early as 913. This also led to an open conflict with Heinrich in Saxony, Berthold and Burchhard in Swabia and with Arnulf in Bavaria.

Relationship with the tribal areas

Saxony

As the brother-in-law of the Babenberger who was executed in 906 and a competitor of the Konradines in northern Hesse and their allies in northern Thuringia, the Saxon Duke Otto the Illustrious was a constant threat to Konrad's kingship. After Otto's death on November 30, 912, Konrad was able to intervene more actively in the situation. On February 3, 913, he confirmed the Corvey Monastery immunity and free election of abbot. During a stay in Kassel on February 18, he confirmed the same rights to the Hersfeld Monastery and privileged the Meschede Monastery in South Westphalia . However, these are the only evidence of Konrad's government activity in Saxony.

According to Widukind, Konrad had doubts about transferring "all the power of his father" to Heinrich. As a result, he incurred the displeasure of the entire army of Saxony. Despite all of Konrad's appeasements, the Saxons had insisted on an undiminished successor and advised the son to resist. With the help of Hatto von Mainz, Konrad tried to turn the worsening situation, but the planned murder with a necklace was betrayed. Instead, Heinrich immediately occupied the Mainz possessions in Saxony and Thuringia and, in addition, expanded his domain to include all of Thuringia. In response to the news of Heinrich's successes, Konrad sent his brother Eberhard to Saxony with an army in 915 . However, this suffered a devastating defeat at the Eresburg , and Eberhard had to flee. Then Konrad himself moved to Saxony with an army.

When the armies met at Grone , Heinrich was militarily inferior to the king. Heinrich is said to have already decided to voluntarily submit to the king (deditio) in order to then close an oath of friendship with him. Count Thietmar was able to induce the Franks to withdraw by cunningly twisting the facts. Widukind's portrayal, however, could be fictitious.

Since a contribution by Heinrich Büttner and Irmgard Dietrich published in 1952, research has assumed a compromise between Konrad and Heinrich in the year 915, even without concrete clues in the sources. Heinrich seems to have performed a deditio (submission) with which he recognized Konrad and his kingship. Gerd Althoff assumes that Heinrich's submission did not fit into the image of the Widukind of the first king as the reason that could have persuaded Widukind to conceal the peaceful agreement and the settlement and to put the anecdote of the cunning Thietmar in its place wanted to draw the Ottonian dynasty.

Apparently Konrad and Heinrich agreed in 915 on the recognition of the status quo and the mutual respect of the zones of influence. Konrad thus refrained from further military interventions in the Saxon-Thuringian border area, while the Duke of Saxony refrained from supporting Alemannic and Bavarian greats with whom Konrad was in conflict. What the relationship between Konrad and Heinrich looked like after 915 remains unclear because of the sources. In addition, the conflict between the king and the southern German rulers now came more to the fore.

Swabia

Unlike in Bavaria or Saxony, where leading sexes were able to establish themselves as duces early on , several aristocratic families competed in Alemannia. The balance of power in the region was extremely unstable during the entire reign of Konrad. As early as 911, Margrave Burkhard von Rätien tried in the Carolingian royal palace of Bodman to rise to the dux or princeps Alemannorum , but was executed after a judgment that was not generally recognized. In the competitive struggle of the local nobility, the Burkhards family was eliminated by killing or exiling their members. The sons Burkhard and Ulrich were sent into exile, the brother Adalbert was killed at the instigation of the Constance Bishop Solomon. Thereafter the Count Palatine Erchanger and Berthold strove for the ducal dignity. The fact that Konrad celebrated Christmas in St. Gallen and Konstanz and then stayed in Bodman and Ulm will also have been understood as a royal demonstration of power.

In 913, following the king's campaign in Lorraine, an open dispute broke out between Erchanger and Konrad. The reason is unknown. In autumn the dispute was settled and the peace agreement was sealed through the marriage of the king to Erchanger's sister Kunigunde . A year later Erchanger captured Bishop Solomon , the representative of royal interests in Alemannia, but was then seized by Konrad himself and sent into exile. In this situation, the younger Burkhard returned and in turn began to rebel against the king. Thereupon Konrad besieged Hohentwiel , which was occupied by Burkhard, in vain and had to withdraw again because the Saxon Duke Heinrich had invaded Franconia. Erchanger then returned from his exile and concluded an alliance of convenience with Burkhard. Konrad reacted with ecclesiastical sanctions: At the Synod of Hohenaltheim , Erchanger and his allies were sentenced to life imprisonment in a monastery. In January 917 Konrad imprisoned his adversaries Erchanger, Berthold and his nephew Liutfrid and had them beheaded on January 21, 917 near Aldingen or Adingen (situation unclear), although they were ready for deditio (submission). The Swabian nobility then elevated their previous opponent Burkhard to duke. Towards the end of Konrad's reign, Burkhard rose again, but Konrad could no longer react.

Bavaria

With his marriage in 913 to Kunigunde, the widow of the Bavarian Margrave Luitpold , who died in 907 , Konrad wanted to strengthen his influence in Bavaria. Bavaria was to be made a basis of royal rule again, as was the case under Ludwig the German. In June 914 Kunigunde was mentioned for the first time in a document as a wife, but the diplomas did not contain any evidence to suggest that the queen played an important role in the royal rule. The fact that Kunigunde chose Lorsch as his future burial place as early as 915 , while Konrad wanted to be buried in Fulda, does not indicate a particularly close relationship between the two.

In contrast to Swabia, the battle for the leadership position in Bavaria was largely decided. After his father Luitpold fell in the battle against the Hungarians in 907, Arnulf was able to gain a powerful and influential position. In Bavaria, however, the entire episcopate stood unanimously behind Konrad, because Arnulf had ruthlessly confiscated church and monastery property and seized church rights. Duke Arnulf tried to evade royal rule in Bavaria and, like Konrad, to gain church sovereignty . The chronology of the dispute is controversial due to the sources. In 916 there was a rebellion by Arnulf, which the king ended with a campaign to Regensburg. Arnulf fled to Hungary. Konrad transferred the rule to his brother Eberhard. A year later, however, Arnulf returned from Hungary and sold Eberhard. During the fighting with Arnulf Konrad was wounded, which he later succumbed to.

Relationship to the Church

Already at the beginning of Konrad's kingship, according to Carolingian tradition, there was close cooperation between the king and the church, which was expressed in the anointing, probably by Archbishop Hatto of Mainz . Almost all Franconian, Alemannic and Bavarian suffragans as well as the archbishops themselves were in contact with the ruler and are mentioned in his diplomas. However, as a rule, they are not detectable at court outside their region, which does not allow the episcopate to appear as the mainstay of Konrad's royal rule.

Around 900 bishops were repeatedly threatened or even killed by the secular nobility. Archbishop Fulko of Reims was assassinated and in 913 this same fate met Bishop Otbert of Strasbourg . The church found itself dependent on a strong kingship and tried to defend it with ecclesiastical means. The bishops played an important role with 39 interveners, i.e. as mediators of a request for confirmation or a donation from the king. In particular, the leading members of the court orchestra and the law firm exerted influence on Konrad. The most important person was Bishop Solomon III. von Konstanz, who held the office of chancellor during the entire reign of the king.

The close cooperation between the Church and the monarchy was expressed by the Synod of Hohenaltheim , convened by the East Franconian bishops on September 20, 916, under the direction of the papal legate Peter von Orte . The synod , which Conrad calls Christus Domini (anointed of the Lord), was intended to strengthen royal power and consolidate the close alliance between the Church and the King. It is unclear whether Konrad himself took part in the synod and which bishops were present. The Saxon bishops did not appear and were strongly reprimanded for this at the synod. Even the importance of Hohenaltheim around 916 is unknown. However, the choice can only be related to the presence of Konrad I in the Bavarian-Franconian border area, since a synod that would have been planned and convened by bishops alone would have chosen an episcopal city as the conference venue. The 38 fully preserved canonical provisions were issued primarily to protect the king and bishops from lay people . Violent acts against the king, Christ Domini , were threatened with anathema . The fact that Heinrich is not mentioned as an opponent of the king at the synod could be evidence of a settlement in Grone of 915. The Bavarian Duke Arnulf, who did not appear, was given a period to face a synod in Regensburg scheduled for October 7th . It is uncertain whether this provincial synod came about. The attempt of the church to strengthen the royal power did not bring the expected success, because Swabia and Bavaria again fell from the king.

Death and succession

It is possible that Konrad and the Saxon Heinrich reached an agreement on the succession in the empire as early as 915 in Grone. Such an agreement is also more likely because Konrad's marriage to Kunigunde, who was already at an advanced age, remained childless after two years. Gerd Althoff deduces from the inclusion of Konrad in two testimonies of Ottonian commemoration of the dead ( Merseburger Nekrolog and St. Gallen Fraternization Book ) that Konrad was most likely to come to an agreement with Heinrich in 915. How the relationship between Konrad and Heinrich developed is unknown. At least further conflicts between the two are not recorded.

Numerous independent reports report that the king was ill until his death. The cause of this illness was evidently the wound he sustained in 916 during an army campaign against Arnulf of Bavaria. The injury also affected his kingship. From 916 until his death, all of the king's documents were issued in places on navigable rivers: Frankfurt (2 ×), Würzburg (2 ×), Tribur and Forchheim . Accordingly, Gerd Althoff concludes, the king had a very limited field of action in his last two years, because during this time he seems to have only traveled by ship, if at all. Due to the long illness and the limited ability to act, Konrad may not have failed because of the resistance of the 'tribal dukes', but rather, according to Roman Deutinger , “ because of the lack of art of his doctors”.

Konrad's body was brought from his place of death, the Weilburg headquarters , to Fulda at his own request and was buried in the church of the Benedictine monastery in Fulda in January 919. Conrad's choice of Fulda as a burial place could be related to the large community of monks and the closeness to Boniface, as a particularly powerful saint guaranteed that the memory of a king would be preserved. The name of Konrad was included in the annals of the dead in the monastery from 779 to 1065 and included in the monks' prayer memories. However, the names of Konrad's predecessors and successors can also be found in the necrological entries, so the entry alone is a very poor indication of Konrad's ongoing prayer.

His successor was not his brother Eberhard , but the Saxon Heinrich. The transfer of power itself is described by Liudprand , Adalbert and Widukind in the same way: Before his death, King Konrad himself gave the order to propose the royal dignity to Heinrich and to bring him the insignia . His brother Eberhard did this. According to Widukind, the dying king himself is said to have ordered his brother Eberhard to renounce the line of succession and the insignia for lack of fortuna (luck) and mores (often translated in research as royal salvation) the highest “state power” (summa rerum publicum ) to transfer to the Saxon Duke Heinrich . However, the unusually long period of five months until Heinrich's elevation to king speaks rather against a publicly pronounced designation by his dying predecessor. Rather, tough negotiations between Eberhard and Heinrich about the successor must have taken place, in which Eberhard had to realize that Bavaria and Swabia went their own way and that he had also quarreled with his relatives.

effect

Measures after Konrad's death

After Konrad's death, between May 14 and 24, 919, in Fritzlar , near the border between the Conradin and Liudolfing spheres, Heinrich was raised to the rank of new king. According to Widukind, the Conradin Eberhard named Heinrich as king before the assembled Franks and Saxons. When the Archbishop of Mainz Heriger offered him the anointing , Heinrich did not accept it: he wanted to be content with having been lifted out of the greats of his empire by the king's name - however, anointing and coronation should be reserved for more worthy people. The representation has sparked heated controversy to this day. For example, there is a dispute over the question of whether anointing was even common in Eastern Franconia. The news that only representatives of the Saxons and Franks were present and the renunciation of the anointing could, however, indicate that Heinrich, in contrast to Konrad, took up his rule with a reduced claim and demonstrated this in Fritzlar.

In order to secure his rule, Heinrich had to regulate his relationship with the dukes. The duces were integrated into the power structures of the East Franconian Empire. Heinrich accepted the establishment of the regional middle powers, the later or future duchies, which Konrad had resisted militarily. The regional rulers possessed power that they did not owe to a grant from the king, but obtained from their own efforts, if you will: through usurpation. With the homage paid to the king , they now gained the legitimation of their leadership role.

Konrad's brother Eberhard became one of the most important men in the empire as amicus regis (friend of the king) and remained so until Heinrich's death. In Swabia, Duke Burkhard is said to have submitted to the king without resistance "with all his castles and all his people". Duke Arnulf exercised de facto royal power from 918 to 921, with which he secured the means of rule of kingship in Bavaria. The much-discussed news in the Salzburg Annals that the Bavarians had proclaimed their Duke Arnulf king in regno Teutonicorum is increasingly being questioned in recent research. Only after more intensive military operations did Duke Arnulf submit to the king. His position of power was not curtailed when he paid homage to Heinrich and was accepted by him as an amicus in the circle of advisors. Heinrich left the duke both the right to assign the dioceses and the treasury with the important Regensburg Palatinate. In addition, Heinrich never had any property in Bavaria in his documents.

In contrast to Konrad, Heinrich did not attempt to appropriate the means of power of the Carolingian kingship, but instead left the principes in the East Franconian sub-empires their leadership role. The dukes, in turn, committed themselves to services and permanent support. Friendship and extensive independence were granted to the dukes, but only after a demonstrative act of subordination.

With regard to the controversial Lorraine, negotiations led to the conclusion of an alliance of friendship between Charles the Simple and Henry. In November 921 the two kings met near Bonn . In the middle of the Rhine, exactly on the border between Lorraine and Eastern Franconia, a ship was anchored, on which the two kings made a treaty . Heinrich recognized Karl's rule over Lorraine, while the latter accepted him as an equal Frankish king, as rex Francorum orientalium or rex orientalis .

Heinrich, like Konrad, was powerless against the Hungarian invasions of 919, 924 and 926. But a Hungarian leader was taken prisoner, and for his release the king bought a nine-year reprieve in return for an annual tribute. In this way you gained time to arm yourself militarily. On March 15, 933, there was indeed a military success in the battle of Riyadh . But only Heinrich's successor Otto was able to permanently end the raids of the Hungarians by winning the Lechfeld Battle of 955.

With Heinrich ended the Carolingian rule of rule, dividing the empire among the king's legitimate sons. The principle of individual succession (succession to the throne) prevailed. Heinrich appointed his son Otto as the sole successor and at the same time founded the Ottonian dynasty .

Konrad in the judgment of the Ottonians

The time of Konrad is one of the poorest sources in the Middle Ages. The chronicle of Reginos von Prüm broke off in 906, the Altaich continuation of the Fulda annals dried up in 901. The annals of the West Franconian historian Flodoard von Reims only cover the period from 919 to 966 again. During Konrad's reign there are essentially only short contemporary ones hagiographic notes. This is also due to the fact that the ruler could not establish a royal family in which the memory of his achievements would have been cultivated.

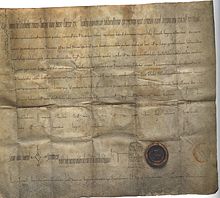

The most important sources for his time are therefore his 38 traditional documents, with which he made or confirmed donations, awards of rights and the exchange of goods. However, half of the diplomas received were issued in the first year and a half of his kingship. After that there are always longer periods from which no diplomas have been handed down. The documents show that the king stayed in Franconia especially in the last two years and that this region became the center of his rule. Beyond the borders of Franconia, the king is almost only traceable in connection with military campaigns. Although the annals cannot provide a coherent picture of history, Konrad appears in these reports as a hapless general who had to leave the defense of the Hungarians to the greats and could hardly assert himself within his rulers.

More detailed reports (with Widukind von Corvey and Liudprand von Cremona ) are not only written from a late retrospective, but also from a Saxon-Ottonian or Italian-Ottonian perspective; they only date from the second decade of Otto I's reign . Their sparse news is evidently due to an oral tradition that later shaped the events fictionally . It is therefore uncertain which details have been passed down correctly.

According to Widukind, who tried to legitimize the rule of the Ottonians, Konrad had only become king of Otto's “the illustrious” (the father of Henry I). Otto had already been offered the crown in 911, but he waived. The Liudolfingers represented the given rulers for Widukind from the very beginning. As a result, the Ottonians and not the Konradines were the real “winners” of the disintegration of the Carolingian Empire in the east.

Nevertheless, Widukind presented Konrad as a powerful and rightful ruler. The follower of the Chronicle Reginos von Prüm called him "an always mild and wise man and a lover of divine teaching". On the occasion of his election, Liudprand of Cremona described him as a "strong and war-experienced man of Frankish sex" who had overcome and subjugated the rebellious princes "through the power of his wisdom and the strength of his bravery". "Had it not been for early death, which knocked on the huts of the poor no more late than on the castles of the kings, King Konrad so early, he would have been the man whose name would have commanded many peoples of the earth."

The Ottonian family prayed for Konrad for a long time. In the Merseburg necrology the king is recorded with the day of his death, December 23rd, and the title rex (king). The St. Gallen fraternization book contains the names of the members of the Liudolfing-Ottonian family who died up to 932 as well as the people with whom the Liudolfing had a good relationship. Among the names of the group for the last days of December there is the name Chuonradus , who is identified with King Konrad.

Afterlife in the High and Late Middle Ages

Konrads was thought of as the founder in Lorsch, Fulda and St. Gallen until the late Middle Ages. In the high medieval chronicles, however, besides the government data, mostly only the Hungarian invasions and the uprisings of the princes were mentioned. The chroniclers of this time tried to structure the history of the Roman Empire according to dynasties, to develop the idea of the translatio imperii and to emphasize the successes of the rulers in particular - Konrad fell victim to these efforts. His kingship was seen as an insignificant interlude that could not be integrated into the idea of continuous rule by the great sexes. Rather, it was found strange that a king could rule who did not come from any of the great dynasties. Some chroniclers therefore simply made him a Carolingian.

Konrad received an extraordinarily favorable assessment from Ekkehard IV of St. Gallen. In this monastery, whose abbot Solomon III. belonged to Konrad's closest circle of advisers, the king was honored for a long time.

In the state, regional and city chronicles of the late Middle Ages, Konrad was almost meaningless. Although it appears in great detail in the Saxon World Chronicle , the news in other chronicles is much more sparse. Konrad is often contaminated with Ludwig the child and called "the last Carolingian". Information about his origin and the exact title of ruler is often missing. Konrad hardly played a role in the collective memory of the late Middle Ages. The Hessian country chronicle of Wigand Gerstenberg is an exception . He celebrated Konrad as the savior of Christianity from the Hungarians. Wigand also made Konrad the largest sponsor of the city of Frankenberg ; he appears to be the originator of a great urban past and thus almost displaces the equally vaunted Charlemagne . It is uncertain why the chronicler Konrad took center stage in such a way.

Konrad's aftermath in documentary sources was limited to the region. The afterlife of Konrad in documentary sources concentrated predominantly on the areas in which he and his family were wealthy or in which the rights and possessions of the Conradins lay. Fulda , Mainz and Würzburg in particular were centers of documentary aftermath. Outside of the Franconian area, its origin was hardly thought of. There are no documents from his house pen in Weilburg , as this institution did not hand over any rulers' documents until the Hohenstaufen era. Konrad's grave was also forgotten; tomb care did not survive the Middle Ages. Its exact location has even been unknown since the 12th century. Perhaps the negative or even missing picture of Konrad has meant that no one bothered to find his grave over the centuries. Only a sandstone plaque installed in 1878 reminds of his grave. Their list hardly met with any public response.

Historical images and research perspectives

Beginnings of the medieval "German Empire"

The fact that the East Franconian greats did not offer kingship to the only Carolingian still ruling , but made a non-Carolingian their king, was often acknowledged as a historical setting for a growing “German awareness”. The decision of the greats from East Franconia, Saxony, Alemannia and Bavaria against a West Franconia was seen as an indication of a strong sense of community on the right of the Rhine in the sense of a "German" national feeling, which is why only one of their own and not a "French" could be considered a king. The fact that the German Reich came into being around the year 900 was a general belief long after the Second World War . The German tribes were seen as the actual founders of the "German Empire". The only disagreement was which specific date between 843 and 936 would be considered.

The historian Harry Bresslau gave a lecture to the Scientific Society in Strasbourg in 1911 with the title “The millennial anniversary of German independence”, in which he assigned Konrad's choice an important role in the demarcation between the Frankish and German epochs of the empire. A change of dynasty, the election of a king and the indivisibility of the empire were the main reasons for Bresslau why he saw 911 as an epoch year. Other historians such as Walter Schlesinger saw in the designation of the Saxon Duke Heinrich by the dying King Konrad an essential contribution to the development of the medieval empire, which they started with the accession of rule in 919.

Johannes Haller let German history begin with Konrad's monarchy and in 1923 introduced his chapter with the words: “Since when has German history existed? The correct answer is: since there were Germans and a German people. But since when has it existed? ... There can only be a German history when the tribes connected to one another break away from the general association of the Frankish Empire and form a unity for themselves. ... Conrad I is therefore considered to be the first German king, and with the year 911 - if one asks about fixed numbers, which of course always retain something external - the first epoch of German history: the emergence of the German state. " In 1972 Wolf-Heino Struck introduced his essay on the founding of Conradin monasteries with the following words: “When Konrad I was elected king in Forchheim in November 911 [...] and thus initiated the history of the German Empire 1060 years ago the dynasty of the Konradiner the high point of its reputation. "

Only as a result of the extensive research into nation-building over the last few decades had such ideas, which were previously considered to be certain, to be abandoned. Today you can see the German Empire emerging in a process that was not yet completed in the 11th and 12th centuries. In addition, it is now undisputed that the so-called gentes , the politically organized large groups that also determined the election of Konrad, were not "German tribes", but German-speaking groups that were linked by an elusive feeling of togetherness and who identified themselves as Franconia, Bavaria, Saxony or Swabians understood, but not as "Germans". The term regnum Teutonicum was used as an external and personal name only gradually from the 11th century.

Konrad in the verdict of research

While the Ottonian sources give the king a positive verdict, according to widespread research Konrad and his entire government are considered to have failed. Despite various campaigns, he was unable to prevent the loss of Lorraine to Charles the Simple, nor was he able to master the emerging Hungarian threat or to integrate the aspiring princes in the regions into the empire. These judgments continue to have an impact today. The research of the 19th and early 20th centuries, which focused more on the emergence of nation states, saw its greatest achievement as accomplished on the deathbed, when he cared for a capable ruler in Heinrich, a decision that Ernst Dümmler praised as "his most honorable act". A similar picture of Konrad can be found in the school books and popular scientific literature of the time. Although the works deal with the Conradin in a comparatively detailed manner, they judged him primarily on the loss of Lorraine and the disputes with the 'dukes' and saw his greatest achievement in the designation of Henry I.

The unfavorable assessment that Konrad experienced in the nationalist 19th century exemplifies a process that occurred in 1891: When Konrad wanted to erect a monument at his former headquarters in Weilburg , the city of Weilburg rejected the project. The rulers and epochs seemed to the “city fathers” to be of all too little importance. The monument was finally erected near Villmar on a rock high above the Lahn , where it still stands today.

Robert Holtzmann concluded in 1941 in his history of the Saxon imperial era : “Judging by success, one can of course only say: it failed. Favored by the clergy, but otherwise almost exclusively based on the strength of the local Rhine Franconia, he suffered defeats on all points. "Two years later, Gerd Tellenbach said :" Konrad I. was not yet able to make the 911 attempt a success. His government is a chain of political failures. "

Such judgments can be found until recently. In 1991 Johannes Fried judged : "Despite some partial successes [...] he overstrains the resources of the monarchy through internal disputes and ultimately fails to defend against external enemies, the Hungarians and Danes". For Fried, Konrad was a king who “failed all along the line”. The absence of Konrad in the relevant ruler biographical series is justified with his unsuccessfulness and the fact that he cannot be assigned to either the Carolingians or the Ottonians.

In a fundamental essay from 1982 dealing with Konrad's notarization practice, Hans-Werner Goetz distinguished between two phases in Konrad's government. In a first phase, which was characterized by “an energetic policy”, he wanted to expand royal rights. His position was strengthened by the broad approval of the great. Only the rebellions of the nascent ducal families initiated the second phase and let Konrad's plans fail and restricted his sphere of activity to Franconia.

Since Goetz's essay, however, no more detailed treatment has been devoted to King Konrad. Konrad classified research more in overarching contexts without granting him a pioneering role. Konrad is only sporadically represented in the youngest generation of textbooks. It was not until a scientific conference initiated by a Fulda citizens' initiative in 2005 that Konrad came back into focus. Hans-Henning Kortüm undertook a “rehabilitation attempt” . In his judgment, Konrad did not fail, on the contrary, he acted extremely successfully. The negative image of Konrad is based on the one hand on the lack of formation of a dynasty and on the other hand on a wrong interpretation of the famous formulation fortuna atque mores , i.e. Widukind's negative summary. According to Widukind, King Konrad is said to have said to his brother Eberhard on his deathbed that he was missing “fortuna atque mores”. While fortuna actually describes happiness, which is so changeable in the medieval understanding, mores is not to be translated as royal salvation , as was customary up to now , but rather with the term zeitgeist . This meaning predominates in the work of Sallust , to whose style Widukind generally orientated himself strongly. The changed translation would ultimately mean that with fortuna and mores a change of ruler took place and the zeitgeist (mores) inevitably turned away from the dying king.

In 2008 Gerd Althoff and Hagen Keller justified the decisive weakness for the failure of Konrad I by saying "that the king did not succeed in building a personal network of relationships that extended beyond the circle with whose help he had taken over the kingship".

On the occasion of the 1100th anniversary of the election of Konrad I as king, the Vonderau Museum organized the exhibition 911 - King Election between Carolingians and Ottonians from November 9, 2011 to February 5, 2012 . Konrad I. - rule and everyday life . An accompanying volume has been published for this purpose.

swell

- Ekkehard IV of St. Gallen : Casus Sancti Galli , ed. Hans F. Haefele (= Freiherr vom Stein memorial edition. Volume 10). Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1980.

- Liutprand of Cremona : Works. In: Sources on the history of the Saxon imperial era (= Freiherr vom Stein memorial edition. Volume 8). Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1971, pp. 233-589.

- Widukind von Corvey : The Saxon history of Widukind von Corvey. In: Sources for the history of the Saxon imperial era (= selected sources for the German history of the Middle Ages. Freiherr vom Stein memorial edition. Volume 8). Translated by Albert Bauer, Reinhold Rau. 5th edition expanded by a supplement compared to the 4th. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2002, ISBN 3-534-01416-2 , pp. 1–183.

literature

- Gerd Althoff , Hagen Keller : The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and consolidations 888-1024 (= Gebhardt. Handbook of German History. Volume 3). 10th, completely revised edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-608-60003-2 .

- Roman Deutinger : The election of the king and the raising of the duke of Arnulf of Bavaria. The testimony of the older Salzburg annals for the year 920. In: German archive for research into the Middle Ages . Volume 58, 2002, pp. 17-68 ( online ).

- Roman Deutinger: Royal rule in the East Franconian Empire. A pragmatic constitutional history of the late Carolingian period (= contributions to the history and source studies of the Middle Ages. Volume 20). Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2006, ISBN 978-3-7995-5720-7 .

- Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the "German Reich"? Winkler, Bochum 2006, ISBN 3-89911-065-X ( conference report ) and ( review )

- Hans Werner Goetz: The last Carolingian? The government of Konrad I as reflected in his documents. In: Archives for Diplomatics . 26, 1980, pp. 56-125.

- Hans-Werner Goetz: "Dux" and "Ducatus". Conceptual and constitutional studies on the emergence of the so-called “younger” tribal duchy. Brockmeyer, Bochum 1977, ISBN 3-921543-66-5 .

- Antoni Grabowski: Konrad I - a king who should be great. In: Archive for Middle Rhine Church History . 70, 2018, pp. 51-70.

- Donald C. Jackman : The Konradiner. A study in genealogical methodology. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-465-02226-2 .

- Gregor K. Stasch, Frank Verse (ed.): King Konrad I. - Rule and everyday life. Accompanying volume to the exhibition 911 - King's Choice between Carolingians and Ottonians. King Konrad the First - Rule and Everyday Life, Vonderau-Museum Fulda, November 9, 2011 to February 6, 2012. Imhof, Petersberg 2011, ISBN 3-86568-700-8 .

- Gudrun Vögler: The Konradines. The family of Konrad I. In: Nassauische Annalen. Volume 119, 2008, pp. 1-48.

- Gudrun Vögler: The King's Reception. Monuments and portraits of King Konrad I in modern times. In: Nassau Annals. Volume 125, 2014, pp. 261-302.

- Gudrun Vögler: King Konrad I .: (911-918). Konrad I - the king who came from Hesse . On the occasion of the scientific symposium of King Konrad I. On the way to the “German Empire”? , Fulda, 21.-24. September 2005; at the same time accompanying volume for the exhibition History - Awareness - Localization shown in Fulda and Weilburg Konrad I. - the king who came from Hesse , June and September 2005. Imhof, Petersberg 2005, ISBN 978-3-86568-058-7 .

- Gudrun Vögler: Medieval portraits of King Konrad I. The examples of the document seals and the Codex Eberhardi. In: Nassau Annals. Volume 122, 2011, pp. 55-76.

- Bettina Wößner: Konrad I. (Eastern France). In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 4, Bautz, Herzberg 1992, ISBN 3-88309-038-7 , Sp. 396-400.

- Walter Schlesinger: Konrad I .. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 12, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-428-00193-1 , pp. 490-492 ( digitized version ).

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ See Wilhelm Störmer: The Konradinischbabenberg feud around 900. Causes, cause, consequences. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 169-183.

- ^ Roman Deutinger: Royal rule in the East Franconian Empire. A pragmatic constitutional history of the late Carolingian era. Ostfildern 2006, p. 214.

- ^ Thilo Offergeld: Reges Pueri. The royalty of minors in the early Middle Ages. Hanover 2001, p. 633.

- ^ Wilhelm Störmer: The Konradinischbabenberg feud around 900. Causes, cause, consequences. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 169–183, here: p. 181.

- ^ D Ko I 3, ed. Theodor Sickel, MGH DD Dt. Kings I, Hanover 1879–1884, p. 3 f.

- ↑ DD LK 35, 64, 67 and 73.

- ↑ Ingrid Heidrich: The noble family of the Konradines before and during the reign of Konrad I. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the "German Empire"? Bochum 2006, pp. 59-75, here: pp. 72 f.

- ↑ Annales Alamannici a. 912 (Codex Modoetinsi), ed. Walter Lendi, Investigations on the Early Manhood Annals The Murbacher Annalen, Freiburg 1971, p. 188.

- ^ Thilo Offergeld: Reges Pueri. The royalty of minors in the early Middle Ages. Hanover 2001, p. 583.

- ^ Thilo Offergeld: Reges Pueri. The royalty of minors in the early Middle Ages. Hanover 2001, p. 618.

- ↑ Hans Werner Goetz: The last Carolingian? The government of Konrad I as reflected in his documents. In: Archives for Diplomatics. 26, 1980, 56-125, here: p. 61.

- ↑ Hans Werner Goetz: The last Carolingian? The government of Konrad I as reflected in his documents. In: Archives for Diplomatics. 26, 1980, pp. 56-125, here: p. 71.

- ^ Tillmann Lohse: Konrad I. as donor. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 295-315, here: p. 299.

- ↑ Verena Postel: Nobiscum Partiri: Konrad I and his political advisers. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 129–149, here: p. 146.

- ↑ Hans Werner Goetz: The last Carolingian? The government of Konrad I as reflected in his documents. In: Archives for Diplomatics. 26, 1980, pp. 56-125, here: pp. 98 f.

- ↑ Thomas Vogtherr: The afterlife of Konrad I in documentary sources. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 329–337, here: p. 331.

- ↑ Widukind, Sachsengeschichte I, 21.

- ^ Widukind, Sachsengeschichte I, 22.

- ↑ Widukind, Sachsengeschichte I, 24. On the identification of Count Thietmar cf. on this Gerd Althoff: Amicitiae and Pacta. Alliance, unification, politics and prayer commemoration in the early 10th century. Hanover 1992, p. 142.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: Amicitiae and Pacta. Alliance, unification, politics and prayer commemoration in the early 10th century. Hannover 1992, p. 20; Johannes Fried: The King's Elevation of Henry I. Memory, Orality and Formation of Tradition in the 10th Century. In: Michael Borgolte (Ed.): Medieval research after the turn. Munich 1995, pp. 267-318, here: p. 293 with note 112.

- ^ Heinrich Büttner and Irmgard Dietrich: Weserland and Hesse in the interplay of forces of Carolingian and early Ottonian politics. In: Westfalen 30, 1952, pp. 133-149. Compare with Gerd Althoff: Amicitiae and Pacta. Alliance, unification, politics and prayer commemoration in the early 10th century. Hanover 1992, p. 19.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: The Ottonians. Royal rule without a state. 2nd expanded edition, Stuttgart et al. 2005, p. 34.

- ↑ D Ko I 23.

- ↑ Ingrid Heidrich : The noble family of the Konradines before and during the reign of Konrad I. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the "German Empire"? Bochum 2006, pp. 59–75, here: p. 74.

- ↑ Roman Deutinger: King's election and Duke's raising of Arnulf of Bavaria. The testimony of the older Salzburg annals for the year 920. In: Deutsches Archiv für Erforschung des Mittelalters 58, 2002, pp. 17–68, here: p. 41 ( online ).

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: The time of the late Carolingians and the Ottonians. Crises and Consolidations 888–1024. Stuttgart 2008, p. 82.

- ↑ Hans-Werner Goetz: The last "Carolingian"? The government of Konrad I as reflected in his documents. In: Archives for Diplomatics. 26 1980, pp. 56-125, here: pp. 91 f.

- ↑ Wilfried Hartmann: King Konrad I and the church. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.), Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 93-109, here: p. 105.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: The Ottonians. Royal rule without a state. 2nd, expanded edition. Stuttgart et al. 2005, p. 34.

- ↑ Hans-Henning Kortüm: King Konrad I. - A failed king? In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 43–56, here: p. 52.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: King Konrad I - King Konrad I in the Ottonian memoria? In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 317-328, here: pp. 320-323.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: King Konrad I - King Konrad I in the Ottonian memoria? , in: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the "German Reich"? Bochum 2006, pp. 317–328, here: p. 324.

- ↑ Roman Deutinger: King's election and Duke's raising of Arnulf of Bavaria. The testimony of the older Salzburg annals for the year 920. In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 58, 2002, pp. 17–68, here: p. 54 ( online ).

- ^ Continuator Reginonis 919.

- ↑ Thomas Heiler : The grave of King Konrad I. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the "German Empire"? Bochum 2006, pp. 277-294, here: p. 279.

- ^ Widukind, Sachsengeschichte I, 25.

- ↑ Johannes Laudage: King Konrad I in early and high medieval historiography. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 340-351, here: p. 347; Matthias Becher: From the Carolingians to the Ottonians. The royal elevations of 911 and 919 as milestones of the change of dynasty in Eastern Franconia. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 245-264, here: p. 261.

- ↑ Widukind, Saxony History II, 26.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: The time of the late Carolingians and the Ottonians. Crises and Consolidations 888–1024. Stuttgart 2008, p. 118.

- ^ Widukind, Sachsengeschichte I, 27.

- ↑ Roman Deutinger: King's election and Duke's raising of Arnulf of Bavaria. The testimony of the older Salzburg annals for the year 920. In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 58, 2002, pp. 17–68 ( online ).

- ^ Bonn Treaty (November 7, 921) c. 1, ed. Ludwig Weiland, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Const. I, Hannover 1893, No. 1, p. 1.

- ↑ On the documents cf. Hans Werner Goetz: The last Carolingian? The government of Konrad I as reflected in his documents. In: Archives for Diplomatics. 26, 1980, pp. 56-125; Thomas Vogtherr: The afterlife of Konrad I in documentary sources. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 329–337, here: pp. 330 ff.

- ↑ Widukind, Sachsengeschichte I, 16.

- ↑ Hans-Werner Goetz: Introduction: Konrad I. - A king in his time and the importance of historical images: 'King Konrad I and the emergence of the medieval empire. In: Konrad I. On the way to the "German Reich"? Bochum 2006, pp. 13–29, here: p. 21.

- ^ Widukind, Sachsengeschichte I, 25.

- ↑ Continuatio Reginonis a. 919.

- ↑ Liudprand of Cremona, Antapodis II, 17th

- ↑ Liudprand of Cremona, Antapodis II, 19th

- ↑ Liudprand of Cremona, Antapodis II, 20th

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: King Konrad I - King Konrad I in the Ottonian memoria? In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 317-328, here: pp. 320 f.

- ↑ Frutolf von Michelsburg, Chronicon a. 912, ed.Georg Waitz, MGH SS VI, Hannover 1844, p. 175.

- ↑ Wilfried Hartmann: King Konrad I and the church. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 93-109, here: p. 98.

- ↑ Jürgen Römer: The forgotten king. The afterlife of Konrad I in the late Middle Ages. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 353–366, here: p. 361. See also Die Chronik des Wigand von Gerstenberg, ed. Hermann Diemar, 2nd edition, Marburg 1989, p. 396 and p. 402–405.

- ↑ Thomas Vogtherr: The afterlife of Konrad I in documentary sources. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 329-337, here: pp. 333 and 336 f.

- ↑ Thomas Heiler: The grave of King Konrad I. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the "German Empire"? Bochum 2006, pp. 277–294, here: p. 293.

- ↑ Walter Schlesinger: The beginnings of the German king election. In: Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History . German Department. 66, 1948, pp. 381-440, here: p. 398.

- ↑ Harry Bresslau: The thousand year anniversary of German independence. In: Writings of the Scientific Society in Strasbourg 14, Strasbourg 1912, pp. 1–16.

- ↑ Walter Schlesinger: The rising of Henry I as king, the beginning of German history and German history. In: Historical magazine. 221, 1975, pp. 529-552.

- ↑ Johannes Haller: The Epochs of German History. Stuttgart 1923, pp. 17-19.

- ^ Wolf-Heino Struck: The foundations of the Conradin monasteries in the memory of the middle Lahn. In: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter. 36, 1972, pp. 28-52, here: p. 28.

- ↑ Hans-Werner Goetz: Introduction: Konrad I - a king in his time and the importance of historical images. In the S. (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the "German Reich"? Bochum 2006, pp. 13–29, here: p. 18. Cf. also: Joachim Ehlers: The emergence of the German Empire. 4th edition, Munich 2012.

- ↑ Jörg Jarnut: King Konrad I and the emergence of the medieval empire. In: Konrad I. On the way to the "German Reich"? Bochum 2006, pp. 265-273, here: p. 267.

- ^ Eckhard Müller-Mertens : Regnum Teutonicum. Appearance and spread of the German concept of the empire and king in the early Middle Ages. Cologne et al. 1970.

- ↑ Ernst Dümmler: History of the East Franconian Empire. Volume 3: The Last Carolingians. Konrad I. (Yearbooks of German History), 2nd edition, Leipzig 1888, pp. 574–620, here p. 618.

- ↑ Robert Holtzmann: History of the Saxon Empire. 4th edition Munich 1961, p. 66.

- ↑ Gerd Tellenbach: When did the German Empire come into being? In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages. 6, 1943, pp. 1-41 ( online ).

- ^ Johannes Fried: The formation of Europe 840-1046. Munich 1991, p. 75.

- ↑ Johannes Fried: The way into history. The origins of Germany up to 1024. Berlin 1994, here: p. 458.

- ↑ Hans-Werner Goetz: Introduction: Konrad I - a king in his time and the importance of historical images. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 13–29, here: p. 25.

- ↑ Hans-Werner Goetz: The last Carolingian? The government of Konrad I as reflected in his documents. In: Archives for Diplomatics. 26, 1980, pp. 56-125, here: pp. 111 ff.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: Konrad I. in school books and popular scientific literature. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 401-411, here: pp. 405 and 411.

- ↑ About the Josef Hoppe initiative in: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the "German Empire"? Bochum 2006, pp. 415-421.

- ↑ Hans-Henning Kortüm: King Konrad I. - A failed king? In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I. On the way to the “German Reich”? Bochum 2006, pp. 43–56, here: pp. 54 f.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: The time of the late Carolingians and the Ottonians. Crises and Consolidations 888–1024. Stuttgart 2008, p. 85.

- ^ Gregor K. Stasch, Frank Verse: King Konrad I. - Rule and everyday life. Accompanying volume to the exhibition 911 - King's Choice between Carolingians and Ottonians. King Konrad the First - Rulership and Everyday Life, Vonderau Museum Fulda, November 9, 2011 to February 6, 2012. Imhof 2011.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

|

Duke of Franconia 906–918 |

Eberhard of Franconia | |

| Ludwig the child |

East Franconian King 911–918 |

Heinrich I. |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Konrad I. |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Konrad the Younger |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | King of Eastern Franconia (911–918) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | at 881 |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 23, 918 |

| Place of death | Weilburg |