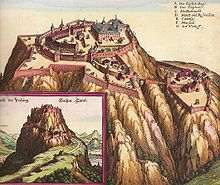

Hohentwiel Fortress

| Hohentwiel Fortress | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Aerial view of the Hohentwiel south view, in the background the BAB 81 and the Hohenkrähen |

||

| Creation time : | At 914 | |

| Castle type : | Höhenburg, summit location | |

| Conservation status: | ruin | |

| Place: | Singing (Hohentwiel) | |

| Geographical location | 47 ° 45 '53 " N , 8 ° 49' 8" E | |

| Height: | 686 m above sea level NHN | |

|

|

||

The fortress Hohentwiel is a former hilltop castle and fortress on the volcanic source crest of Hohentwiel in Hegau , close to the Lake Constance . The rocks tower over the town of Singen , located at the eastern foot of the mountain, by 260 meters. With an area of nine hectares , the fortress, which is accessible to visitors, is the largest castle ruin in Germany. Since 1990, the facility has been visited by over 80,000 people every year, the maximum in 2002 was 126,520 visitors. The Hohentwiel Festival takes place annually in the area of the fortress.

In its history, the fortress was also an early medieval ducal seat and a simple high medieval castle. The fortification on the Hohentwiel is mentioned for the first time in 915. In the following period, the Hohentwiel was owned by various noble families , including the Zähringer and Klingenberger . At the beginning of the 16th century, the Hohentwiel came more and more under the influence and rule of the Württemberg people . The castle was again the seat of the ducal. In the following centuries, the complex was expanded to become the Württemberg state fortress and besieged five times without success in the Thirty Years' War . It was then used as a state prison until the facility was razed in 1801 in the Second Coalition War . After the destruction, the ruins quickly became a magnet for tourists.

Location and surroundings

The Hohentwiel volcano with the fortress is located in the south of Baden-Württemberg on the outskirts of the city of Singen in the district of Constance . The city is located directly below the east side of the mountain on the banks of the Radolfzeller Aach . To the west is Hilzingen, three kilometers away . Lake Constance is ten kilometers to the south-east. In the northwest and north are the ruins of Hohenstoffeln , Hohenkrähen Castle and Mägdeberg Castle , which are also located on striking volcanic remains .

Origin of name

The castle is first mentioned in the St. Gallen monastery chronicle of Ekkehard IV (around 980-1060) as castellum tuiel, which was besieged in 915. Previously, researchers assumed the name had Celtic roots. According to the latest findings in linguistics, an Alemannic origin is assumed because of the initials . The word could then go back to the Indo-European tribe * tú or tuo with the meaning swell . This assumption is not certain. The name appears in Latinized in documents as a duellium or duellum . Since the transition from the late Middle Ages to the early modern period , the name Hohentwiel has been in use alongside “Tuiel” or “Twiel” . It is first recorded for 1521.

history

Beginning as a ducal seat

In contrast to the other Hegaubergen, no traces of a refugee castle could be found on the Hohentwiel . The origins of the fortifications on the mountain go back to the early Middle Ages , in connection with the re-establishment of the Duchy of Swabia . In 914 the mountain was fortified by Burchard II during his uprising against King Konrad I and was besieged by Konrad the following year without success. Burchard was able to prevail and was officially enfeoffed with the duchy by Konrad's successor Heinrich I around 920 . Under his son, Duke Burchard III. , the Hohentwiel was expanded to the Swabian ducal residence in the middle of the 10th century.

In 970 work began on building a monastery on the Twiel . It was the St. Georg and had an attached monastery school. Burchard III died in 973. and was buried in Reichenau Monastery. His widow Hadwig was able to maintain her position on the Twiel for 21 years until her death in 994 and was even referred to as dux (dt .: duke) in royal documents . This is remarkable in that there were two other legitimate dukes during her lifetime. Around 973 she summoned Ekkehard II from the Abbey of St. Gallen on the Hohentwiel to be taught Latin by him. Ekkehard's life was described in the historical novel Ekkehard by Joseph Victor von Scheffel in 1855 ( see below ).

After Hadwig's death, Emperor Otto III. zum Twiel, in order to settle the inheritance there and to claim the rights to the royal estate that Hadwig assumed for himself. In the year 1000 the emperor stayed a second time on the Twiel, which suggests a comfortable expansion of the castle, but also shows Otto's efforts to enforce his claims to ownership.

Medieval aristocratic castle

Around 1005 the monastery was relocated to Stein am Rhein , after which the Twiel lost its importance. The next documentary mentions are related to the investiture dispute . In 1079 the Hohentwiel obviously belonged to the Zähringers . Adelheid, the wife of the opposing king Rudolf von Rheinfelden and mother-in-law of Berthold II von Zähringen, died that year on the Hohentwiel.

In this context, two families appear who both named themselves after the Twiel, but cannot be identical due to the political constellation: one appointed by the Abbot of Sankt Gallen and one from the Zähringer community. Ulrich von Eppenstein , abbot of the St. Gallen monastery , was able to remove Twiel from Berthold in 1086, which then remained under the abbot's sphere of influence for over three decades. After the abbot's death in 1121, the Lords of Singen , who were in the service of Zähringen, took possession of the Twiel (presumably in 1122 at the earliest, but in 1132 at the latest) and from then on called themselves "Lords of Twiel". In 1214 a Gibizo de Twiel and in 1230 a Heinrich von Twiel are recorded. Heinrich is the last proven master of Twiel. It is unclear whether these people owned the Twiel themselves; it could also have been royal or ducal property. Then those named were the Twiel belehnt been.

There is a document signed by Ulrich von Klingen from 1267 . After the Zähringers died out in 1218, the Lords of Klingen could have appropriated the Twiel and transferred the Lords of Twiel to the Rosenegg . Another Ulrich von Klingen sold the Twiel on February 16, 1300 for 940 silver marks to Albrecht von Klingenberg . The Twiel remained in the possession of the Klingenberg family for seven generations. In 1419 and 1433 Caspar von Klingenberg bought the rule of Hohenklingen and the bailiwick of the St. Georg monastery. After more than 400 years, the Lord of Twiel was again the patron of the monastery.

In 1464 a feud began between Eberhard von Klingenberg and Johann von Werdenberg . The Werdenberger had captured and tortured a servant of Eberhard. In the course of the events, two coalitions were formed: the Werdenbergers with the knight society Sankt Jörgenschild and the Counts of Württemberg on the one hand and Eberhard with Hans von Rechberg , Wolf von Asch and Swiss rice walkers on the other. Eberhard was able to fall back on the latter, as he had become citizens of the city of Lucerne in 1463 . After all attempts to mediate had failed, the siege of Twieler Castle began on October 11th by the Werdenbergers together with the knight society. Nothing is known about major fights during the events on the Twiel. The Rechberger castles were also besieged. In the course of such a siege, Hans von Rechberg died on November 11th, whereupon Eberhard turned to Archduke Siegmund of Austria with a request for mediation . As a result, on January 28, 1465, a peace agreement was reached in Biberach . Earlier, on January 12, Eberhard had admitted that the Lords of Klingenberg would become the Archduke's servants for 200 guilders .

After several members of the Klingenberg hereditary rule claims to the Ganerbenburg had raised Twiel, it came in 1475 to a truce : Between Eberhard, Kaspar the Elder and the Younger, Albrecht and Heinrich agreed, the castle not for sale, which because of the financial Would have offered trouble to the family. However, the lack of money meant that Albrecht and Kaspar the Elder. Ä. 1483 in the service of Eberhard the Elder for six years . Ä. from Württemberg stepped. This thus obtained the right to use the two shares in the Twiel. In 1486, Bernhard von Klingenberg signed a service contract with the Württemberg resident, which meant that he could dispose of the castle if necessary. On the other hand, Kaspar d. Ä. 1485 to the Austrian Archduke, which secured Kaspar's share of the Twiel. In 1489 Albrecht did the same. This situation was precarious insofar as the interests of Württemberg and Habsburg, both of which were trying to unite their territories with their respective possessions in Alsace and Burgundy, clashed in the Hegau. During the Swiss War of 1499, the Twiel was not attacked despite numerous fighting in Hegau.

Württemberg fortress

In 1511 Duke Ulrich von Württemberg received the right to open the Twiel part of Hans Heinrich von Klingenberg. As a result, there were family disputes, in the course of which Hans Heinrich won more and more parts of the Twiel. When Duke Ulrich had to flee from the Swabian Federation in 1519, his right of opening allowed him to take refuge on the Twiel. In 1521 Ulrich acquired the right to use the Twiel in order to use it as a location for the reconquest of Württemberg. The contract stipulated that the Twiel should revert to Hans Heinrich two years after the successful reconquest. In addition, high financial promises were made to the Klingenberger. Duke Ulrich tried to use the unrest of the Peasants' War to recapture his land. At the beginning of 1525 there were 500 Swiss mercenaries on the Hohentwiel who were supposed to support Ulrich. In total, Ulrich had gathered between 6,000 and 8,000 soldiers in the vicinity. The campaign was broken off again before Stuttgart because the French king had been captured near Pavia and the Swiss mercenaries were therefore recalled.

After Ulrich regained his duchy nine years later, the agreed return of the castle did not come about. Instead, Ulrich acquired the Hohentwiel in full on May 24, 1538. He paid 12,000 guilders for it. After the experience of his expulsion, in which all his castles had fallen, Ulrich wanted to build seven state fortresses, one of them on the Hohentwiel. The expansion of the castle was financed with financial support from the French King Franz I. The duration of the work is not known. In 1550 Duke Christoph , Ulrich's successor, had the fortress expanded. In addition, the Bruderhof was bought by Singen in order to get a domain to supply the fortress. In 1593 the Bergmaierhof was added.

Thirty Years' War

The old rivalry between the now Protestant Württemberg and the Catholic Habsburg continued in the Thirty Years' War . Between 1627 and 1634 the fortress was further strengthened. After its initial defeat in the Battle of Wimpfen in 1622, Württemberg initially pursued a policy of neutrality. However , the edict of restitution issued by Emperor Ferdinand II in 1629 , according to which all spiritual goods that were not Protestant at the time of the Passau Treaty of August 1, 1552, were to come back into Catholic hands, reunited the Protestant estates and allied themselves in the Heilbronner Bund with the Swedish King Gustav Adolf II. After their defeat in the battle of Nördlingen on September 6, 1634, Württemberg was open to the enemy. Eberhard fled to Strasbourg with his court . All state fortresses except for the Hohentwiel were conquered by the imperial. Ferdinand III. regarded Württemberg as an area conquered by Habsburg and administered it accordingly. The Protestant estates now allied themselves with France. In 1635 Bernhard von Weimar took command of the Protestant troops, but in May 1635 the Elector of Saxony, who later joined most of the other imperial estates, made the peace of Prague with the emperor. The edict of restitution was withdrawn, the Catholic League dissolved and only one imperial army was to be set up against external enemies (Sweden, France). However, the members of the Heilbronner Bund were expressly excluded. Bernhard von Weimar then placed himself in French service. France openly entered the war and southwest Germany became one of the main theaters of the war. 1638 received Duke Eberhard III. part of his duchy returned, but the offices given away by Ferdinand II remained with Habsburg.

The Hohentwiel fortress now played a decisive role as an important base for the Habsburg opponents, who were allied with France. Konrad Widerholt was appointed commandant in 1634. One of his first tasks was to restore discipline and secure supplies. The correspondence received between Widerholt and Duke Eberhard in Strasbourg mainly revolves around the procurement of money and food. Money could sometimes be obtained indirectly via Switzerland, but in general, Wiederholt was on his own. In 1635 he had a windmill with horizontal blades built on the fortress, an idea that he probably brought with him from Venice. He had “useless” people, that is women and children, removed from the fortress, and he even thought at times about reducing the crew from 124 to 45 men.

One means of raising money was kidnapping. In February 1635 the Sulzische bailiff Kullig was kidnapped in Jestetten , which brought in 3700 guilders. The Fürstenberg Major von Salis, who was captured in Aach , brought 20 horses. The kidnapping of the Bishop of Constance, who was at a hunters' meal in Bohlingen , did not succeed, but the horses captured were enough to release 39 men who had been captured in a battle over the high crows . Nevertheless, the arrears of wages in the middle of 1635 were already 3000 guilders.

The fortress was besieged for the first time from August 1635 to February 1636. At the same time, the plague spread in Hegau, and the fortress was also affected, with 150 deaths. The first siege ended with a contract, according to which the raids should be stopped and the supply of the fortress was assured. 1637 wanted Duke Eberhard III. von Württemberg handed over the Hohentwiel to the emperor in order to be reinstated as duke, but this failed because of Widerholt's refusal. Instead, Widerholt placed himself under the command of Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar , who was subsequently able to make conquests in southwest Germany. Between July and October 1639 the fortress was besieged for the second time by Gottfried Huyn von Geleen , presumably the forecourt was also briefly occupied. Repeatedly was still supposed to hand over the fortress, but he did not, despite the prospect of impunity and a large sum of money. The third siege by Spanish troops took place in September 1640 and the fourth siege in the winter of 1641/42. The attackers came so close that they could shell the fortress from close by, but suffered heavy losses from the wintry weather and broke off the siege when it became known that relief troops were approaching. After that, the defenses were further strengthened. In 1644 there was the fifth and last siege by Franz von Mercy . The fortress was not attacked directly, but sealed off over a large area. This siege also ended unsuccessfully.

On March 14, 1647, a separate peace was concluded between France and Bavaria in Ulm. On October 24, 1648, the Thirty Years War ended with the Peace of Westphalia. On November 29, 1648, Widerholt announced the return of the fortress to his duke, but the ceremonial handover did not take place until August 10, 1650. On August 12, 1650, Colonel Konrad Widerholt abdicated. On August 17th, Duke Eberhard III came. even to the fortress. Konrad Widerholt was enfeoffed with the Neidlingen manor and died on June 13, 1667 as Obervogt von Kirchheim unter Teck .

State prison until the demolition

In the following years the fortress was expanded again and again, for example in 1653, 1700 and 1735. This year the maximum expansion stage was reached. From 1658 the Duchy of Württemberg used the fortress as a state prison , but also as a safe refuge for the ducal family. During the War of the Spanish Succession , the Hohentwiel was prepared for defense from 1701 to 1714, but there was no fighting. Duke Eberhard Ludwig stayed at the fortress on March 17, 1702. Between August and October 1741, the young Duke of Württemberg Carl Eugen and Princes Ludwig Eugen and Friedrich Eugen were housed on the Hohentwiel for their protection due to the War of the Austrian Succession . From 1759 to 1764 Johann Jacob Moser was a political prisoner in the state prison. In the second half of the 18th century, the fortress increasingly lost its military importance, which was reflected in the demolition and failure of the reconstruction of buildings in the Lower Fortress. After 1787, members of the Hannikel robber gang were prisoners in prison. In 1799, Duke Friedrich II stayed in the undestroyed fortress for the last time.

Following the impetus of the French Revolution triggered revolutionary wars of the Hohentwiel was inspected in 1798 by the Austrians. When the French marched into the Hegau in 1799, the Hohentwiel initially remained unmolested. On May 1, 1800, the Austrians withdrew from Singen after the French had crossed the Rhine. Soldiers from Vandamme's division reached the fortress. The commanders of the Hohentwiel initially rejected the requested handover of the fortress and invoked the neutrality of Württemberg. But finally they signed the surrender at 11 p.m. in the Singen rectory. The next day the crew left and the fortress was sacked by the French. In August 1800 the razing of the Hohentwiel was decided in Paris . The fortress was razed from October to March 1801.

Later modern times

In 1804 a makeshift repair was carried out for a visit by Frederick II. In 1810, the surrounding area came under the Treaty of Paris to Baden , while the Hohentwiel remained as a crown property with Württemberg. Negotiations to solve the exclave problem failed in 1847. After 1821, rebuilding the fortress was repeatedly considered. In 1849 the Hohentwiel came to the city of Tuttlingen . In the First World War, an aerial guard was stationed at the Hohentwiel 1915-1918. Such a guard was also on the mountain during World War II . When the Allies approached Hohentwiel and Singen in 1945, the fortress was opened as a shelter for citizens. The fortress was shelled several times by French tanks on April 27, damaging the Augusta rondel and the Wilhelmswacht.

On January 1, 1969, the Hohentwiel officially began to sing. However, the fortress remained with the state of Baden-Württemberg.

Building history

The building history of the Hohentwiel can be divided into three sections, analogous to the function of the buildings: the mountain was fortified with a castle for 500 years. At the end of the Middle Ages under Württemberg it was expanded into a fortress. This existed almost 300 years before it was destroyed. But work has also been done on the ruin since then, mainly to make it safer for visitors.

In its greatest extent from 1735 the area of the fortress comprised 9 hectares (ha) and 92 ares (a) . The upper fortress was 2 ha and 18 a, the lower fortress 2 ha and 12 a. The remaining 5 ha and 62 a were accounted for by the surrounding earth fortifications.

Castle

The first evidence of a fortification at or on the Hohentwiel relates to the year 914. There is only speculation about the condition of the facilities at that time. Presumably they were constructions made of wood and earth. It is also not known whether the systems existed before this date. Where the ducal residence of Burkhard III. found is also not clear. In 970 the monastery of St. George was founded. There is no archaeological evidence as to whether the residence and monastery were on the mountain itself or on the so-called Hohentwiel terrace - in the area of today's domain - and whether there was only a fortress fortified with palisades on the mountain . In the area of today's “Herzogsburg” west wall, wall structures that are attributed to the 14th or 15th century have been preserved.

The castle in the 15th century

The shape of the late medieval castle can be reconstructed on the basis of the castle truce document of 1475 and an inventory list, which was drawn up on June 21, 1521 on the occasion of the sale of the castle to Duke Ulrich von Württemberg.

Through a torhuss ( gatehouse ) one got into a forecourt. A brugken und steg (bridge and footbridge) led to a ussern torren (outer tower), which secured the entrance to the actual sloß (castle). This comprised an area of 30x23 meters, the rear end of which was built on with a multi-storey building measuring 11x22 meters. The following rooms can be determined using the inventory lists: a lower chamber (1) with an antechamber (2), a large chamber (3), a women's room (4) and a maiden's room (5); A corridor led to a room (6), a room in front of the boys 'chamber (8) and the boys' chamber (7), as well as a well chamber (9); an all-round covered battlement (10), from which one came into a Pfaffenkammer (11); a small (13) and large chamber (12), a letter chamber (archive) (14), Mr Albrecht's chamber (15) with a woman's room (16), a good room (17), a small chamber (18) and the kitchen room ( Spinning room) (19). The castle chapel, which, as the Pfaffenkammer proves, certainly existed, and the castle kitchen are not mentioned. This is probably due to the fact that the inventory primarily recorded the accommodation options. Therefore mainly the beds were listed that were everywhere except in the living room - a total of 44 beds. Even in the well chamber there were two and on the battlement there were eleven wide beds that were obviously designed for multiple occupancy. In the truce of 1475 it is mentioned that each of the two parties had to provide 15 servants on certain occasions, and also when documenting military services at the end of the 14th century, the Klingenbergers usually appeared with around 15 servants. The furniture consisted of troughs ( chests ). There was a box (cupboard) and several kensterlin (small, lockable cupboards). There were only tables in the rooms. The table in Albrecht von Klingenberg's room is explicitly designated as a desk. In the two adjoining rooms to this room there were two traveling chests belonging to the council in Austrian service. Bumiller assigns the room sequence 3–7 to Hans Heinrich von Klingenberg, his wife Susanna von Rotberg, their daughters Susanna and Clara and their son Hans Caspar. He attributes the room sequence 14-18 to Albrecht von Klingenberg and his wife Dorothea von Ottingen. The other rooms were intended for the servants or, like the kitchen and well room, were shared. The description suggests that both complexes extended over several floors. If one assumes that the well room and kitchen as well as other storage rooms were on the ground floor, the residential wing could have consisted of three floors.

The well did not carry groundwater, but was a cistern . The water was transported daily from the donkey fountain on the western ascent to the castle with donkeys to the castle. This also explains the abundant wine stocks in the castle - according to the inventory from 1475, 4 loads (approx. 7000 liters). The inventory also lists ten pigs that were kept at the castle all the time, three quintals of lard, 6 quintals each of peas, lentils, beans, flour and barley, 300 quintals of grain (half spelled, half rye) and ten slices of salt.

Complete masonry and carpentry crockery was also kept available for the maintenance of the castle. In the inventory from 1521 there is also a complete set of forged dishes.

Between 1475 and 1521 there was an armament at the castle, which is reflected both in the arsenal and in the amount of supplies: 173 measure of lard , 37 sides of bacon , meat in large quantities, 81 cheese, 161 pounds of salt, 196 pounds of pork pain , 20 Fuder (around 35,000 liters) of wine, three barrels of tree oil . The inventory also provides information on other farm buildings that can no longer be assigned today. In addition to the three wine cellars, there were 72 Malter rye (approx. 210 quintals) in an upper granary and in "Junkers", ie Hans Heinrichs Kornhaus, 72 Malter rye, 60 Malter Müller grain and three Malter barley. In stables and on pastures around the mountain there were 15 cattle, seven calves, 17 pigs, 10 (work) horses with carts and harness and six donkeys.

The military inventory reflects both the changing war technique and the armament of the castle. In 1475 the castle was equipped with four winch crossbows and 2,000 associated arrows. There were also five hand pipes and arquebuses with three hundredweight gunpowder and two hundredweight lead . In 1521 there were 25 crossbows, plus six hand tubes and 54 arquebuses as well as large artillery in the form of two field snakes and eleven smaller falcons. This also increased the supply of ammunition: 40 quintals of black powder , four quintals of saltpeter , three quintals of sulfur and 40 quintals of lead. Later, in 1616, at the time of the fortress, there were 47 heavy artillery pieces and 612 small arms.

fortress

→ See: List of buildings on the Hohentwiel between 1591 and 1735

The conversion from the aristocratic seat to a fortress and garrison was carried out by Duke Ulrich from 1521. This also changed the primary function from an economic and administrative seat to a primarily military facility, whereby the increasing spread of firearms in the early modern period made appropriate adjustments to the defense facilities necessary. In the first few years, the expansion was managed by foremen from Montbéliard . A 220x60 foot basement and a 200x24 foot vault were built in the Upper Fortress in 1522 . In 1523 another vault was built, a ditch with a chute for grain and three cisterns . The Klingenberg castle on the summit was completely renovated, only the central structure remained. Its walls later became the inner wall of the duke's castle. The surrounding area was leveled so that two plateaus were created. The barracks building found its place on the eastern one , with the excavated material from which the western plateau was heaped up. The areas were then surrounded with a wall that enclosed the entire summit. Two gun turrets were built on the south-east and north-east side of the wall around 1526: "Wilhelmsturm" and "Gutgenug". This strengthened the relatively flat east side of the Hohentwiel. The towers were accessible from the barracks through a covered corridor. The "Scharfes Eck" gun turret was built on the west side. A windmill was also built on the summit until 1527, but it never worked properly. It is not known when the Klingenberg forecourt was expanded into the Lower Fortress ; In 1588 it was secured by a wall with half-shell turrets for small guns. The time of the fortification of the "Schmittefelsen" is also unclear, which could have happened in the early construction phase.

Between 1550 and 1557 Ulrich's son Christoph spent 45,000 guilders on construction work on the Hohentwiel. From 1553 to 1554 he had the old Klingenberg castle rebuilt into a renaissance castle , today's Herzogsburg. Its three wings surrounded an inner courtyard on an almost rectangular base. In 1559 a gate was built on the forecourt as a further representative building, possibly in connection with the above-mentioned enclosure of the forecourt. A wine press house and a building to house wagons were also built under Christoph . The time when the "Rondell Augusta" was built is not clear. Due to its location, it dominated the western apron and made the "sharp corner" superfluous. From this one can conclude that the Rondell was built under Christoph at the earliest, perhaps even under his successor Ludwig. The Rondell is a gun turret with a diameter of 25 meters. In 1593 the first meierhof was built below the fortress.

In the early phase of the Thirty Years War, when there was no fighting in Hegau, the Hohentwiel was expanded again. Between 1627 and 1634 the Upper Fortress was reinforced with bastions , especially the east side. Two bastions were built here and the “Schmittefelsen” was also expanded into a bastion. In 1635, commandant Widerholt had a windmill built. A church was built between 1639 and 1645, the inventory of which was stolen from the area. After the war ended, the Lower Fortress, which had been destroyed several times during the war, was rebuilt. The gate building was renewed and withdrawn into the inner area. A little further to the west, the "Eugenstor" was built. A new cellar was also built, which later served as an officer's accommodation. In addition, the farm buildings and living quarters were expanded. A residential building, which later became a pharmacy, and an inn were built. In order to better secure the fortress, the access was changed: A crown work (its western part is today's "Karlsbastion") was created around the forecourt, and the entrance to the fortress was via the new Karlstor. Under pressure from Austria, which was critically observing the expansion, work that had already started on a fort in the area of the Lower Fortress had to be stopped.

An inspection of the defenses in 1727 revealed that the walls were in poor condition. As a result, repairs were carried out in August of that year. In the following years there were further extensions: the defensive ring was continued on the upper fortress between the small bastion ("triangle") in the south and the Augusta roundabout. This created a defense terrace ("St. Erdmann"), on which a tree garden was initially created. Hardly any new buildings were built, instead existing buildings were used differently: the church also served as a warehouse, and the former mill building became a soldiers' accommodation. The Wilhelmswacht became a sutler's shop . Only a few smaller houses, a windmill tower and a tower at the ducal seat were built. A sutler's shop and a hospital were also built in the Lower Fortress. A garden was laid out on the Ludwigsbastion on the south side, presumably to make the fortress more self-sufficient in times of siege . The entrance was reinforced by the construction of the Alexander Gate. In 1735 the fortress reached its maximum level of development.

ruin

Most of the construction work that was carried out in the ruins after it was razed in 1801 can no longer be reconstructed today. During and after the razing, a lot of material was stolen from the population. The fortress was cleared for Frederick II's visit in 1804. Large areas of rubble had to be removed and potential dangers from loose stones in the walls removed. The roads were made passable for wagons and the bridges to the Upper Fortress made passable. The costs for these measures amounted to 2,496 guilders. Around 1845 the church tower, which served as an observation tower, was repaired and the first observation platform was built. In 1847 the bridges were closed and in 1849 they were renewed in a smaller form. Around 1900 the dilapidated stairs of the Augusta roundabout were repaired. In 1912 the south wall of the Upper Fortress was renovated. The Karlsbastion was also built; it was made safer for visitors in 1920 by building a railing wall.

The problem with the Hohentwiel building fabric is that the mortar is washed out of the historical masonry by rain and the walls lose their stability as a result. In addition, frost blast attacks the walls. The growth of ivy and trees also destroys the building fabric. To prevent the disintegration is the task of the construction work up to the present day. The walls must also be secured against slipping. For example, they are artificially connected to one another or anchored in the rock with drill anchors. Between 1978 and 2000 around 5 million DM were spent on maintenance work. Until 2007, the state of Baden-Württemberg had a further 2.4 million euros available. From 1974 to 2009, 4.76 million euros were invested in securing the ruins.

Resident development

Information on the number of residents has existed since the beginning of the fortress period. It is first documented that women and children lived in the fortress in 1594. If necessary, however, the fortress was able to accommodate significantly more soldiers. During the Peasants' War in 1524, 500 soldiers were stationed in the fortress.

|

|

The welcome book

At the solemn repossession by Eberhard III. In June 1652, when he was on the Hohentwiel with a large entourage and many guests, he donated a leather-bound guest book made of high-quality paper made in Zurich. Over the course of 148 years, it recorded around 900 rhymes and sayings in German, French, Latin, but also Greek and Hebrew from visitors to the fortress. The guest book followed on from a tradition established by Duke Ulrich, according to which every visitor to the fortress was obliged to carry 40 pounds of stones up the mountain, but was entitled to a welcome drink from a golden cup above.

Eberhard III. opened the book with the French motto "Tout avec Dieu" ( Eng. Everything with God). The three later major visits to the princes are each documented with a large number of entries: Eberhard Ludwig on March 17, 1702 , Karl Alexander with a large retinue in 1734 and, as a result of the War of the Austrian Succession, the young Duke Carl Eugen with his brothers Ludwig Eugen and Friedrich Eugen in 1741 .

Many of the entries refer to the custom of carrying stones : "I carried a stone on Hohentwiel / 50 pounds is not much, / but drank wine from the cup / God will continue to be gracious to me" , wrote on April 12, 1697 a Freiherr von Ow, to which a Count von Forstner replied: "I didn't carry it heavily, / I drank the more." On the other hand, the entry by the secretary and secret registrar Johann Christoph Knab, who accompanied the three ducal brothers in 1741, reflects the anxiety Escape: "If someone is looking for me in Stuttgart / So I speak to you on the run, / To Hohen Twiel, on rock and stone, / Where rough air and sour wine, / I forget all about pleasure, / The fox will get it , so to blame. "

In addition to such entries, there are entries from officers of the fortress, from pastors and clerical dignitaries and, in the 17th century, from many young aristocrats from Sweden, Pomerania, Saxony or Westphalia who visited Hohentwiel on their cavalier tour. From 1734 onwards the first entries were made by women and in the 18th century by commoners.

Ekkehard novel

In 1855 Joseph Victor von Scheffel's novel Ekkehard appeared , which was reprinted 89 times during Scheffel's lifetime. The focus of the story is the love story between the monk Ekkehard II and Hadwig , the widow of Duke Burchard III. At the beginning of the novel, Hadwig travels to St. Gallen and meets Ekkehard there. Enthusiastic about the educational inventory of the monastery, she challenges Abbot Ekkehard as a Latin teacher. On his trip he spent the night in the Reichenau monastery and had an argument with the local monks. This is followed by an attack by the Huns, who are defeated in a battle in front of the Hohentwiel. Ekkehard also takes part in the battle. After Ekkehard laughed at a Belgian monk, he took revenge with a diatribe that was leaked to the Duchess by the Reichenauer. This and his refusal to woo them, but ultimately his attempt at advances at the wrong moment, brings him into the castle dungeon. Ekkehard was able to flee and hid with alpine farmers in the Säntis area. Here he writes the “Walthari Song” and then travels the world to experience unknown adventures.

Unlike in the novel, Ekkehard II was only Hadwig's teacher and confidante. In reality, the Hungarian invasions corresponded to the "invasion of the Huns" . The Hungarians came to Hegau in 913, 915 and 917, the role of Hohentwiel in this is not known. The Walthari song corresponds to the real Latin Waltharius heroic poetry, which was written around the 10th century. However, its author is not known. Scheffel translated the poetry from Latin into German. For his novel, Scheffel made extensive use of the sources available around 1850, so that parts of the novel are closely based on historical reality.

The representations of the novel, which was at times extremely popular, influenced the perception of the history of Hohentwiel for a long time. Many readers took them to be reality. This also affected the ruins. Faulty signs were attached to some buildings under the impression of the novel, for example monastery, later barracks or Ekkehardsturm . No traces have been found in the ruins from the 10th century.

Bismarck relief medallion by Theodor Bausch

The fortress today

On a tour through the preserved parts of the fortress, starting from today's "Domain Hohentwiel", you first reach the lower fortress through the Alexander Gate (1), a tunnel. The heavily destroyed Karlstor (2) in front of the Karlsbastion (3) follows . The Eugenstor (4) leads to the interior of the Lower Fortress. Past the gate building Radschinen (5), the staff officers' building (6) and the old wine press (7) you pass the pharmacy (8), the sutler's shop (9) and the barracks (10). In the ascent to the Upper Fortress you can see the bakery (11) and a farm building (12). In the upper part of the path you come across the remains of a gate tower, the Salzbüchsle (13), which is followed by the forge (14). The northernmost part of the fortress is the Friedrichsbastion (15) on the Schmittefelsen . You can then enter the Upper Fortress through a portal (16). This begins with the long building (17, barracks) in which the arcade is located. The eastern part of the Upper Fortress is dominated by the Paradeplatz (18), on which the cisterns (19) are located. From the square there is a passage to the Gutgenug turret (20). In the barracks there is an exit to Wilhelmswacht (21), the eastern bastion. At the southern end of the eastern part is the upper bakery (22), to which the nave of the church (23) connects to the north . In the western part of the upper fortress is the Herzogsburg (24) with the bathhouse (25). The southernmost point is bounded by the Eberhardswacht (26), which merges into the Augusta roundabout (27) to the west. To the north of this is the armory (28).

Festivals and festivals

As early as 1900, the city of Singen wanted to establish the Hohentwiel Festival . For this purpose a festival hall was built under the Hohentwiel, where two festivals took place in 1906 and 1907. In the years that followed, however, the project proved a failure and the hall was demolished in 1918. After the First World War, the idea of the festival was revived. On a weekend in August 1921 the festival took place again, this time directly in the courtyard of the Herzogsburg. In 1922 it became the Volksfestspiele , which ran for six weeks. The location of the performances was the Karlsbastion, with the lower and upper castle as a "natural" backdrop. With varying financial success, the festival continued every year until the Great Depression in 1929. From 1935 to 1939 there was the German Festival under National Socialist leadership and with support from Joseph Goebbels .

When the Hohentwiel came to the town of Singen in 1969, a special festival week was organized in the summer to mark the occasion . Among other things, there was a castle festival with fireworks. The festival weeks were repeated in 1970, but without program items in the fortress itself. In 1975, a jazz festival took place on the Karlsbastion , which was subsequently held regularly. In 1980 it enlarged so that the Lower Fortress was included. In the same year there was a cultural Sunday with thirteen venues spread across the fortress and 20,000 visitors. From 1981 the jazz festival was extended to two game days, and the cultural Sunday became a mountain festival . In 1990 Miles Davis appeared at the festival, which was also able to establish itself internationally. In 1998, savings in the Singen city budget meant that the festival was only possible with private partners. In 2000 there were no events on the mountain because of the state horticultural show . The festival has been held annually since then. Today the festival lasts a week and takes place in July. The festival is organized by the city of Singen in cooperation with KOKO & DTK Entertainment from Constance.

tourism

Tourist visitors to the Hegau and Hohentwiel have been around since the beginning of the 18th century; for example, Johann Georg Keyßler and Johann Georg Sulzer came . However, the fortress could not be entered without the permission of the court in Stuttgart. This was only possible for church services. After the castle was razed at the beginning of the 19th century, the Duke of Württemberg was the first visitor in 1804. As a result, the fortress could be entered free of charge, 12 cruisers had to be paid to climb the church tower . A "tourist" measure was the reforestation of the Hohentwiel after 1890, which should give the mountain a "friendlier appearance". In May 1906, Kaiser Wilhelm II visited the Hohentwiel. In 1994 an information center with ticket sales, a permanent exhibition and a multimedia show was set up in a coach house in the domain. The number of visitors to the fortress has been over 50,000 annually since the 1950s and more than 80,000 annually since 1990. In 1990 and 2002, 120,412 and 126,520 visitors, respectively, exceeded the 120,000 mark. In 2008, 86,000 people visited the ruins. The fortress ruins are looked after by the State Palaces and Gardens of Baden-Württemberg .

literature

- Herbert Berner (Ed.): Hohentwiel, pictures from the history of the mountain . 2nd Edition. Thorbecke, Konstanz 1957

- Casimir Bumiller: Hohentwiel: The story of a castle between everyday fortress and great politics . 2nd Edition. Stadler, Konstanz 1997, ISBN 3-7977-0370-8

- Roland Kessinger (ed.), Klaus-Michael Peter (ed.): Hohentwiel book - emperors, dukes, knights, robbers, revolutionaries, jazz legends . MarkOrPlan, Singen (Hohentwiel) / Bonn 2002, ISBN 3-93335-617-2

- Roland Kessinger (Ed.), Klaus-Michael Peter (Ed.): 1. Appendix 2004/05 to the Hohentwiel Book . MarkOrPlan, Singen (Hohentwiel) / Bonn 2004, ISBN 3-93335-627-X

- Roland Kessinger (Ed.), Klaus-Michael Peter (Ed.): New Hohentwiel Chronicle (2nd appendix 2009/10 to the Hohentwiel book). MarkOrPlan, Singen (Hohentwiel) 2009, ISBN 978-3-93335-655-0 .

- Josef Weinberg: The commandant from Hohen-Twiel ; Kurt Arnold Verlag, Stuttgart 1938, 359 pp. Historical novel, focus are the 5 sieges.

- Immanuel Hoch : The last fate of the Württemberg fortress Hohentwiel. In addition to the life of their vice-commanding officer, Colonel Freiherr von Wolf, and the story of their strange state prisoners . Stuttgart 1837 ( e-copy ).

- Eberhard Fritz: Konrad Widerholt, commandant of the Hohentwiel Fortress (1634-1650). A war entrepreneur in the European power structure . In: Journal for Württemberg State History 76 (2017). Pp. 217-268.

Web links

- Casimir Bumiller: Hohentwiel. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Website of the Hohentwiel fortress ruins

- Virtual Hohentwiel tour

- Official website of the Hohentwiel Festival

- Illustration by Daniel Meisner from 1626: Hohenwyhl. Periculo alieno sapere ( digitized version )

- 3D model of the Hohentwiel Fortress

Remarks

- ↑ See also the dispute between Württemberg and Habsburg over the neighboring Mägdeberg .

- ↑ Günter Restle ( The medieval castle on the Hohentwiel . In: Hegau-Geschichtsverein: Hegau Jahrbuch . Volume 44/45, 1986/87. (Pp. 19–43)) represents this thesis. Casimir Bumiller ( Hohentwiel . (P. 38ff)) sees the assumption that the residence and monastery were on the mountain top not explicitly refuted.

- ↑ The numbering follows Bumiller ( Hohentwiel . (P. 86f.)) And serves below to distinguish the living areas of the two families Albrechts von Klingenberg and Hans Heinrichs von Klingenberg.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Casimir Bumiller: Hohentwiel . (P. 16f).

- ^ Roland Kessinger: Swabian ducal residence - The early Twiel . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 19).

- ^ Roland Kessinger: Swabian ducal residence - From the Franconian Empire to the German Empire . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 20ff).

- ↑ Klaus-Michael Peter: The descent to the Adelsburg - The Lords of Twiel - 2 gentlemen of one name? . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 32ff).

- ↑ New Hohentwiel Chronicle . (P. C22).

- ↑ a b c d Roland Kessinger: The knight festivals Twiel . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 41ff).

- ^ Roland Kessinger: The expansion to the state fortress . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 65ff).

- ^ A b Roland Kessinger: The expansion to the state fortress . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 65ff).

- ↑ Casimir Bumiller: Hohentwiel . (P. 147f).

- ↑ Casimir Bumiller: Hohentwiel . (P. 148).

- ↑ Casimir Bumiller: Hohentwiel (p. 167).

- ^ Roland Kessinger: State fortress and state prison . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 165ff).

- ^ Roland Kessinger: Revolution, Napoleon and coalition wars . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 199ff).

- ↑ New Hohentwiel Chronicle . (P. C30ff).

- ^ Roland Kessinger: State fortress and state prison . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 186).

- ↑ New Hohentwiel Chronicle . (P. C20ff).

- ↑ a b Casimir Bumiller: Hohentwiel . (P. 88).

- ↑ Casimir Bumiller: Hohentwiel . (P. 90).

- ↑ Roland Kessinger: The expansion to a state fortress - expansion of the Hohentwiel to an early modern fortress . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 76f).

- ↑ Roland Kessinger: The expansion to a state fortress - expansion of the Hohentwiel fortress under the dukes Christoph and Ludwig . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 91f).

- ↑ Roland Kessinger: The 30 Years War - The Hohentwiel in the first phase of the war - construction work . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 110f).

- ↑ Roland Kessinger: The 30 Years War - Construction work under repeated . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 147).

- ^ Roland Kessinger: State fortress and state prison - expansion after the 30-year war . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 170ff).

- ^ Roland Kessinger: State Fortress and State Prison - The Herbotsche Plan of 1735 . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 170ff).

- ↑ Roland Kessinger: 1100 years of building history - further construction and maintenance measures after the fortress was destroyed . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 234f).

- ^ Gunther Braun: 1100 years of building history - preservation of monuments at Hohentwiel . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 240ff).

- ↑ a b Hohentwiel is being refurbished . In: Südkurier of May 29, 2009.

- ↑ Casimir Bumiller: Hohentwiel . (P. 172ff).

- ↑ Klaus-Michael Peter: Romanticism and Realism - Hadwig and Ekkehards Hohentwiel will not be taken away from us . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 253ff).

- ↑ Tour of the fortress . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 272ff).

- ↑ Klaus-Michael Peter: Friend and Sorrow for the Hohentwiel . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 265ff).

- ^ Walter Möll: Festival Fortress Hohentwiel . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 279ff).

- ↑ Klaus-Michael Peter: The Hohentwiel Information Center . In: Hohentwiel book . (P. 303).