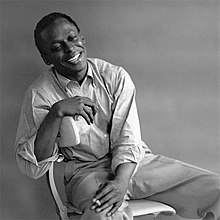

Miles Davis

Miles Dewey Davis III. (* 26. May 1926 in Alton , Illinois; † 28. September 1991 in Santa Monica , California) was an American jazz - trumpet - flugelhorn player , composer and band leader and one of the most important, influential and innovative jazz musicians of the twentieth century. After taking part in the so-called bebop revolution, Davis significantly influenced the development of various jazz styles such as cool jazz , hard bop , modal jazz and jazz rock . Both as an instrumentalist and as a creative spirit, Miles Davis was able to realize his own artistic ideas and at the same time be commercially successful.

Miles Davis first gained fame as the bebop jazzman and sideman of Charlie Parker . In the 46 years of his musical career he worked with musicians such as John Coltrane , Herbie Hancock , Chick Corea , Joe Zawinul , John McLaughlin and Gil Evans . Since he regularly brought talented musicians, from whom he expected new impulses, into his band and gave them space to develop, numerous jazz greats owe their breakthrough as musicians to the collaboration with Davis.

Since the end of the 20th century, his albums and compositions have received great acclaim from music critics and fans alike. They are considered classics and masterpieces of jazz. Davis himself was named best trumpet player. As a special tribute to the work of Miles Davis, the United States House of Representatives passed a symbolic resolution on December 15, 2009 to mark the 50th anniversary of the recording of his album Kind of Blue, "honoring the masterpiece and affirming that jazz is a national treasure" .

Life and musical career

Youth 1926–1944

Miles Davis was born the middle of three children into a wealthy family. His father, Miles Davis II, was a dentist and the family owned a farm in Millstadt, east of East St. Louis . His mother Cleota was born Henry; Based on the maternal name, Miles Davis used the pseudonym Cleo Henry on some early recordings. He had an older sister, Dorothy, and a younger brother, Vernon. Both parents were music lovers and, like his older sister, played an instrument. When he was three years old, his family moved to East St. Louis to a non- segregated neighborhood (which was not officially abolished until 1964). There he had a carefree childhood. When he was nine years old, a friend of his father's gave him his first trumpet . After receiving a new instrument and trumpet lessons from Elwood Buchanan, a friend of his father's, at the age of thirteen, clear progress was noticeable and he played in the high school band. From the age of fourteen he took lessons from Joseph Gustat , the then principal trumpeter of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, and received a solid trumpet training.

Davis became friends with Clark Terry during his time in high school, where the atmosphere was more socially excluded than in his living quarters . The confident, cool demeanor and trumpet style of the six-year-old man had a great influence on the young Miles Davis. At sixteen, Davis joined the musicians' union. Around 1942 his relationship with Irene Birth, who went to the same high school, also began. At seventeen he played for a year with Eddie Randles Blue Devils in St. Louis and the surrounding area. During this time he got an offer to tour with the Tiny Bradshaw Band , but his mother insisted on a high school graduation. In 1944, at the age of eighteen, his girlfriend Irene had their first daughter Cheryl. Since Irene had other loves, Miles Davis wasn't sure if Cheryl was his child. Regardless, he took financial responsibility for her. Davis had three children with Irene Birth, but never married.

Bebop and Cool Jazz 1944–1955

In 1944 Davis moved to New York City on the pretext of attending the Juilliard School of Music. In fact, he began his studies, but there he mainly went looking for Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker . After just a few semesters, he broke off his studies because the training there was too limited, classic and too "white" for Davis' taste. Miles Davis himself in his autobiography:

“I still remember a course in music history. The teacher was white. She stood in front of the class and explained that blacks play the blues because they are poor and have to pick cotton. That's why they're sad and that's where the blues comes from, from their sadness. My hand shot up like lightning and I got up and said, 'I'm from East St. Louis and have a rich father, he's a dentist. But I also play the blues. My father didn't pick any cotton in his whole life and I didn't wake up a bit sad this morning and then played a blues. There's a little more to it than that. ‛The aunt turned really green in the face and didn't say another word. Man, what she told us came from a book that must have been written by someone who had no idea what he was talking about. "

At the same time he accused Parker and Lester Young of dealing too little with European music. Davis himself often went to the public library to borrow scores from representatives of New Music or the Schoenberg School such as Igor Stravinsky , Alban Berg , Sergei Prokofiev and other composers.

He was now a member of Charlie Parker's quintet and made his first recordings with Charlie Parker ( The "Koko" session ) in November 1945 . Although Davis' trumpet style was already well developed, he lacked the confidence and technical virtuosity of his role models. His father sympathized with his son and encouraged him: “Miles, do you hear the bird out there? It's a mockingbird . She doesn't have a voice of her own, she just imitates the voices of others and you don't want that. If you want to be your own master, you have to find your own voice. That's what it's about So just be yourself. "

In 1946 Davis went to the West Coast with Benny Carter's Big Band , where he wanted to make bebop known on the West Coast in Los Angeles together with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie . In the same year, Irene gave birth to their second child, Gregory. As Charlie Parker's heroin addiction became more of a problem, Miles Davis began to focus on his solo career, working with Gerry Mulligan , Gil Evans, and others towards starting a nonet . This was also the beginning of a twenty-year collaboration with Gil Evans. In order to achieve the desired sound, such unusual instruments as the tuba and the horn were used in jazz . In September 1948 this group performed for the first time. The nonet dissolved just a year later, but had previously made twelve recordings for Capitol Records , which were not sold too successfully as shellac records . The recordings only became really famous in 1957, when they were released as a long-playing record under the title Birth Of The Cool . Their influence was already felt before in the jazz scene, as they contributed to the development of cool jazz , which was picked up by Chet Baker , Stan Getz and Shorty Rogers and soon set the tone.

In 1949 Miles played in the band of the pianist Tadd Dameron and appeared with him at the Paris Festival International 1949 de Jazz . In 1950 he returned from Paris, where he fell unhappily in love with Juliette Gréco . Treated like a star in Paris, he saw himself confronted with racism in the USA and at the same time consumed drugs to the point of addiction. He shared this dependency with many of his colleagues, for example Chet Baker , Billie Holiday , Sonny Rollins and Stan Getz . During this time, his son Miles Dewey Davis IV was born and the family moved to East St. Louis. Shortly thereafter, the relationship with Irene Birth broke up.

Davis played many sessions over the next several years, but too often without the necessary dedication. Due to his addiction and the associated damage to his image, he was only able to make recordings for small labels such as Prestige or Blue Note . In January 1951 his first session took place for the prestige label, Miles Davis and Horns , with John Lewis and Sonny Rollins , among others . However, he did not manage to keep a firm group together. At this time he met his future wife, Frances Taylor, who worked as a dancer in a nightclub in Los Angeles . To break free from drugs, he moved back to East St. Louis in 1954. There he got rid of his addiction with the help of his father. So that he could keep his distance from the New York drug scene, he went to Detroit for the time being .

In March 1954 he came back to New York. There he soon discovered the Harmon damper , which he played as a Wee-Zee damper without a stem . This damper shaped the sound of many of his pieces from then on and he would use it for the rest of his life. Over the next year a number of important recordings were made for the prestige label ( Walkin ' and Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants ). Due to the further development of sound technology for long-playing records, it was now possible to record jazz pieces that were longer than three minutes. Davis now had the opportunity to put his skills to the test in longer solos, such as the more than thirteen-minute walkin ' , which became a groundbreaking piece for the jazz musicians of the time, but was not yet adequately recognized by the critics .

Miles Davis made his big comeback in July 1955 when he came on stage unannounced at the Newport Jazz Festival for three pieces and played a legendary solo at Monks ' Round Midnight . This performance led George Avakian to sign him at Columbia , although he also had a contract to perform at Prestige. He obtained permission for this from Prestige by convincing them that Prestige would benefit from the advertising of the much larger record company Columbia on the outstanding recordings.

The first quintet and sextet 1955–1958

In 1955 Davis founded the Miles Davis Quintet. The band, consisting of John Coltrane ( tenor saxophone ), Red Garland ( piano ), Paul Chambers ( bass ) and Philly Joe Jones ( drums ), quickly became famous. In order to fulfill the contract with Prestige, the quintet recorded four albums ( Workin ' , Cookin' , Steamin ' and Relaxin' ) within two days . The fact that the quality of the albums did not suffer from this assembly line work shows how well the quintet worked back then. In addition, the album 'Round About Midnight' was recorded almost simultaneously for Columbia . During this time Miles Davis became a real star on the jazz scene.

In 1957 Davis recorded the album Miles Ahead together with arranger Gil Evans , with whom he had already worked on Birth of the Cool , which was lavishly orchestrated and left him little room for improvisation. Still, he was very happy with his work. Exceptionally, he played almost all of the recordings with the flugelhorn. Miles Ahead as well as the subsequent Porgy and Bess (1958) became a commercial success. Because of their drug excesses, Davis replaced Coltrane and Jones with Sonny Rollins and Arthur Taylor . But he was not completely satisfied with the sound of the new quintet and hired the alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley . In the meantime Rollins and Red Garland had left the quintet. The new pianist was Tommy Flanagan . When John Coltrane got over his drug addiction, Davis wanted to bring him back. Before that he went to Paris to play with Kenny Clarke's quartet. When he was introduced to Louis Malle , he was persuaded to write and record the music for the film Ascenseur pour l'échafaud (Elevator to the Scaffold). The recordings were made in just one night, which introduced Davis to a whole new way of working in the studio. Instead of great planning, the focus was on short instructions and spontaneity , a technique that would later also be used on albums such as Kind of Blue or Bitches Brew . Back in New York, Davis put together his dream sextet by bringing Coltrane and Garland back. After a few appearances, the group recorded the album Milestones , which, thanks to Adderley's contribution, contained not only bebop but also somewhat more bluesy pieces. In addition, the newly emerging modal jazz was further developed. Miles Davis played a pioneering role in the development of this style. During the recordings, there was a dispute between Garland and Davis, so that the latter played the piano himself on the piece Sid's Ahead . Around the time Bill Evans replaced Garland, Philly Joe Jones left the band for good. Since Jones left the sextet shortly before a performance in Boston, his replacement Jimmy Cobb had to travel from New York. He set up his instrument while the band was playing: that's how his engagement with the Miles Davis Sextet began in the middle of 'Round Midnight .

At the end of May there was a reliable and musically polished version of the sextet with the two newcomers, which was to exist in this form for seven months and gathered again in the studio for Kind of Blue . When Bill Evans left the group because the constant touring was draining him, Red Garland was brought back briefly to replace him with Wynton Kelly when he was again late for a gig .

Kind of Blue 1959-1964

This was the formation with which Miles Davis went into the studio in the spring of 1959 and recorded his legendary album Kind of Blue . Bill Evans returned for it and left Wynton Kelly the piano for the piece Freddie Freeloader only . In two sessions on March 2nd and April 22nd, an album was created that is exemplary of modal jazz and, according to Columbia Records and the RIAA, the best-selling jazz album of all. The album was awarded the fourth platinum record by the RIAA in 2009 for more than four million albums sold in the United States. The music magazine Rolling Stone leads Kind of Blue number 12 in the list of the 500 best albums of all time .

But the innovative musicians who were responsible for the class of this album made sure that the sextet did not last too long. John Coltrane was persuaded to do one last European tour in the spring of 1960 before he left to form his own band. Cannonball Adderley had already left the group in the fall of 1959, and Davis tried out various substitutes for the two saxophonists, including Sonny Stitt and Hank Mobley , who was performing at his concerts at the Black Hawk in San Francisco .

On December 21, 1960, Miles Davis married his girlfriend Frances Taylor. She became his first wife. In April of the following year he recorded a concert for the first time explicitly for an LP release at the Black Hawk in San Francisco. In 1961 he was diagnosed with sickle cell anemia . While he was now doing well financially and moving into a five-story house on the Upper West Side of Manhattan , musically he was a bit on the spot at the time.

In 1963 the rhythm section, consisting of Kelly, Chambers and Cobb, left the band. Davis quickly formed a new band with George Coleman on saxophone and Ron Carter on bass. Later drummer Tony Williams and pianist Herbie Hancock joined the group, which recorded the album Seven Steps to Heaven in 1963 . Davis was enthusiastic about this formation from the start. The repertoire consisted mainly of bebop and standards, which were already known from Davis' earlier bands and were now played with more rhythmic and structural freedom. After his appearance with the new band at the Antibes Jazz Festival , he worked again with Gil Evans to record The Time of the Barracudas with him .

Davis' mother died in late February 1964. To relieve the joint pain caused by sickle cell anemia, Davis drank plenty of alcohol and used cocaine , which put a heavy strain on his marriage. In the same year Coleman left the quintet and the avant-garde saxophonist Sam Rivers took over for a short time ( Miles in Tokyo ) . Since Rivers was oriented towards free jazz , a style that Davis rejected, he continued looking for a saxophonist. In the summer of 1964 he brought Wayne Shorter to Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers to leave and join him. Shorter was reluctant to do so, having become Art Blakey's musical director.

The second quintet 1965–1968

With Tony Williams (drums), Herbie Hancock (piano), Ron Carter (bass), Miles Davis and the newly added Wayne Shorter, Miles Davis' second great quintet, which would be his last acoustic group, was formed. This line-up is familiar to jazz lovers as The Second Miles Davis Quintet . Many compositions of this period came from the pen of Wayne Shorter, who, like Herbie Hancock, made several important records under his own name parallel to his work with Miles Davis. Due to the high level of improvisational interaction , the recordings made by this group are considered classics and a prime example of successful inside-outside improvisation , which the quintet mastered perfectly. In 1965 the formation recorded the album ESP , which introduced new compositions and a new game concept. In the same year, Davis was left by his wife, Frances, after a violent altercation. Davis had to undergo hip surgery in April. Since the operation failed, another one was necessary in August, so he could not recur until November. Shortly before Christmas, during a guest performance in Chicago, the recordings from the "Plugged-Nickel" ( Live at the Plugged-Nickel ) were made , which show how well the open interaction of the band has now worked. But in January 1966 Davis fell ill with liver inflammation and had to sit out again for three months.

In the following years a series of other records was made: Miles Smiles (1966), Sorcerer (1967), Nefertiti (1967), Miles in the Sky (1968) and Filles de Kilimanjaro (1969). But the sales of the albums sank rapidly, which is certainly not least due to the fact that the music of the quintet was rhythmically and harmonically extremely complex and could not be easily understood by the general public. Miles Davis once again proved to be an innovator in the title number of Nefertiti (1967): in the piece for which Shorter is identified as the composer, the rhythm section takes on the improvisational development, while the winds remain in a kind of ostinato : a role reversal that is called was new in jazz. In 1967 tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson joined the band for some time; However, no recordings were made with him. At this time Miles Davis met his future wife Cicely Tyson , with whom he had a relationship in 1967. As the year progressed, the band began the unusual practice of playing their live concerts in continuous sets, with one piece flowing seamlessly into the next. Davis' bands were to keep this technique until his temporary withdrawal from music in 1975. In late 1967 Davis began experimenting with the Fender Rhodes piano in the studio . He also brought guitarists into the studio to expand his quintet , including George Benson . On the albums Miles in the Sky and Filles de Kilimanjaro Davis used electric instruments for the first time; the albums pointed the way to Davis's fusion phase. Wayne Shorter wrote most of the pieces back then. In 1968 Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter left the quintet. Davis replaced them with Chick Corea (piano) and Dave Holland (bass). Both the new and the old line-up can be heard on the album Filles de Kilimanjaro . On September 30, 1968, Davis married the 23-year-old singer Betty Mabry ; her face can be seen on the cover of Filles de Kilimanjaro , a visual sign of the trend-setting influence she had on Davis. During the short period of their relationship - the marriage broke up in 1969 - she introduced him to the music of Jimi Hendrix, among other things, and thus initiated the fusion elements in the new music by Davis, which permeates the album Bitches Brew.

The development towards Bitches Brew 1968–1970

Towards the end of the 1960s, Miles Davis began to reorient himself musically. The Davis biographer Eric Nisenson reports on a visit by Leonard Feathers in June 1968 to Davis in Hollywood with the aim of recording the interview for a blindfold test for down beat . It struck him that the trumpeter disdained the then current New Thing albums such as Freddie Hubbard and Archie Shepp and instead listened to music by the Byrds , Aretha Franklin , the 5th Dimension or James Brown . Of all the albums Feather played for him, only two he liked, one from the 5th Dimension and one from the psychedelic band The Electric Flag . His then-wife Betty Davis, who Jimi Hendrix counted to her favorite musicians, had a strong influence on Miles' musical preferences . Miles Davis demonstrated this interest in new musical directions as early as December 1967 when he invited guitarist Joe Beck to record with the quintet and had Herbie Hancock use an electric Fender Rhodes piano for the first time . Another step was taken with the change from Hancock to Chick Corea or from his previous bassist Ron Carter to Dave Holland , with whom additional recordings were made for the last quintet album Filles de Kilimanjaro .

In November 1968 Davis brought two more keyboard players, again Herbie Hancock and the native Austrian Joe Zawinul ; for Tony Williams came the drummer Jack DeJohnette . The extended group recorded two of Zawinul's compositions, "Directions" (in two different versions) and "Ascent". Eric Nisenson wrote of the recordings:

“The main difference was that the musicians he worked with could react spontaneously to the improvising soloist. With this session Miles discovered a method of combining seemingly incompatible elements: the use of electronics and the freedom of improvisation, the spontaneous music of the moment, which for him was still the quintessence of jazz, and the multi-layered timbres that in the past could only be realized through complicated orchestral arrangements. Miles did not find this first session completely successful, but it opened up new possibilities for him. "

In February 1969 Miles Davis recorded the album In a Silent Way , with which the "stylistic turnaround", "the complete liberation from the bop concept took place" The record represents a fusion of jazz and rock and is one of the first ever fusion albums . In addition to his quintet, Davis brought the young English guitarist John McLaughlin into the studio for the recording session . Herbie Hancock also came back, and Joe Zawinul, whose keyboard style, according to Herbie Hancock, only released Miles Davis at this stylistic change, completed the line-up, which together with Chick Corea now comprised three keyboard players. The new thing about the album was the great musical freedom that the musicians were allowed to enjoy. A real song concept was hardly recognizable. In addition, the long improvisations by Davis and the producer Teo Macero were intensively reworked. The tracks that were eventually released on the album were compilations from various sessions, and the producer's influence on the finished product was greater than ever before with Miles Davis. Teo Macero, with whom Davis had worked regularly since Sketches of Spain , remained an important partner for his work for the near future. In the end, the album only consists of two pieces, each filling a complete record page. After these recordings, Tony Williams left the band to form his group Lifetime . He was replaced by Jack DeJohnette . At that time, Miles Davis divorced his wife Betty.

In August 1969, Davis went into the studio to record Bitches Brew , which was released in 1970. The album is one of the milestones in his work. The line-up of In a Silent Way was expanded to include other musicians, for example Bennie Maupin . The principle of In a Silent Way was taken even further, and a completely new interpretation of jazz emerged. In contrast to previous jazz, the band did not simply consist of the usual wind instruments, acoustic piano and bass, and drums. For the first time electrical instruments dominated. At this time Davis began to amplify the sound of his trumpet and to influence it with effect devices such as the wah-wah pedal. Up to three drummers and two bassists also played at the same time. The rhythm was no longer dominated by swing, but by elements of funk and some rock music styles that are similar to funk. The post-production was more important than in traditional jazz recordings and was a real part of the creative process. The piece Pharaoh's Dance, for example, consists of nineteen cuts to structure the recorded sound material.

Both albums, especially Bitches Brew , were a huge commercial hit for Miles Davis. For Bitches Brew he got a gold record for the first time in the USA for 400,000 units sold at the time. It was his best-selling work at the time. It was not until much later, in 1993, that it was overtaken by the Kind of Blue , published eleven years earlier . During this time he toured with the Lost Quintet , consisting of himself, Shorter, Corea, Holland and DeJohnette, supplemented by the percussionist Airto Moreira from the beginning of 1970 . From the middle of the same year Keith Jarrett expanded the group, whose energetic keyboard playing drove the individual sets, which were played without interruption, to sometimes wild and exciting highlights. Keith Jarrett himself said in the interview on the Another Kind of Blue DVD that he hadn't really made a musical contribution to this band, but maybe added something like energy. The group played medleys from the last two albums, the records of the second quintet, but occasionally also old standards, such as Ray Charles ' What I say .

The development of the years 1970–1975

With his new direction, Davis attracted a large audience from the rock music field while discouraging some old fans. The band has supported rock bands such as the Steve Miller Band and Santana . Carlos Santana was well aware of Davis' musical importance and said that he should have played in the opening act and not the other way around. In 1970 Davis appeared several times in Bill Graham's Fillmore East and Fillmore West, both great forums of rock music at the time, and not least at the Isle of Wight Festival with an appearance that could hardly be overestimated in terms of its musical history. The departure of Chick Corea at the end of 1970 focused and concentrated the music more on rock and funk on the one hand, and on the other hand it took away much of the free jazz elements and the complex rhythm, which Miles Davis regretted at the time, because he tried in vain Keeping Chick Corea in the band. Dave Holland also left the band to join Chick Corea to found the much-acclaimed free jazz trio Circle .

His place was taken over by the young Stevie Wonder bassist Michael Henderson , whom Miles Davis Stevie Wonder is said to have lured away with the words: "I'll take your fuckin 'bassist". This choice changed the music of Miles Davis decisively. The virtuoso, fun-oriented, rhythmic and no longer jazz-oriented playing of the bassist gave Miles Davis the basis to radically change his trumpet playing. At the end of the year Miles Davis began playing the trumpet with the wah-wah pedal - probably for the first time on December 17, 1970 at the Cellar Door performance, after the December 16 performance was still unplugged . His fellow musicians reported that the electrically amplified trumpet was already ready for several performances, but was not used. From December 18, Miles Davis was no longer to be heard unplugged for almost five years. The Cellar Door appearances ushered in the extremely productive touring year 1971. Miles Davis' music was hailed as the main event at major jazz festivals in Europe and Japan. Joachim-Ernst Berendt , then director of the Berlin Jazz Days , described Davis' performance in his announcement before the performance as the most important of the entire festival. The time of club appearances was over, the Miles Davis Band filled the great concert halls of the world. The concerts consisted of a single medley, usually almost two hours long, played without a break. Miles Davis began to change the line-up of the band. He aimed for a more circular grouping of musicians and often played half turned away, with his back to the audience or bent low over the wah-wah pedal, which eventually became his controversial trademark.

In 1972 Davis had to undergo gallstone surgery. He had health problems all year round. With the album On the Corner he consciously tried to reach the black mass audience. The keyboard surfaces of In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew gave way to hard, almost abstract funk rhythms and a dense network of percussion . However, the success was moderate, most critics panned the musically radical album in sharp form. It wasn't until decades later that On the Corner was recognized as an album that was way ahead of its time and had not been understood when it was released. In 1998 the record was included in The Wire's selection "100 Records That Set the World on Fire (While No One Was Listening)" .

In October 1972, Davis was in a car accident in which he broke both ankles. The following year, his partner Jackie Battle separated from him. He also took more and more cocaine. Meanwhile he played the organ more and more often at his concerts . Its popularity fell again. Despite health problems, he continued to play countless concerts and recorded new titles, including He Loved Him Madly , a work dedicated to Duke Ellington , which was published on Get Up with It . During the Japan tour in January and February 1975, he took eight painkillers a day to get through the tour. Pangea and Agharta , two live albums recorded on February 1, 1975 on this tour, are still considered the most important live albums of electric jazz today . The band consists of Al Foster (drums), Mtume (percussion), Michael Henderson (bass), Pete Cosey (guitar, synthesizer, "water drum"), Reggie Lucas (guitar), Sonny Fortune (alto saxophone) and Miles Davis (trumpet and organ), was closed and avant-garde. The recommendation printed on the albums "We suggest that you play these records at the highest possible volume to fully appreciate the sound of Miles Davis" could be seen live by anyone who saw the band between 1973 and 1975. With huge, black-power -colored loudspeaker towers, Miles Davis, consistently hidden behind dark sunglasses and playing with his back to the audience, and his musicians kindled a deafening dense network of improvised funk jazz that only developed with little thematic material. Rock, which drove away the last jazz fans back then.

After an Easter concert in St. Louis, Miles Davis was hospitalized with a bleeding stomach ulcer . Shortly after eighteen were him polyps in larynx removed. On September 5th he played in Central Park , New York . It was to be his last concert by 1981. Other planned concerts had to be canceled due to health problems. In December he was operated on again on his hip. Miles Davis also felt drained artistically.

The withdrawal from 1975–1981

From 1975 to early 1980, Davis did not pick up his instrument; H. he did not give concerts. During this time he consumed large amounts of alcohol , analgesics , heroin and cocaine . Nevertheless, recordings were made with guitarist Larry Coryell and pianist Masabumi Kikuchi in early 1978 , but they were not published. Davis only plays the keyboard on it. Columbia published archive recordings during this time in order to bridge the time until the next newly recorded album, because Miles Davis, like only Vladimir Horowitz , had a lifelong contract with the CBS, from which he was entitled to regular payments.

In retrospect, the development of Miles Davis' music between 1968/69 and 1974/75 took place with an astonishing speed and consistency. He no longer had a jazz concept, but his own concept with which he was equally open to jazz, classical music, blues, soul, funk and rock music. While Davis retired in 1975, fusion jazz was developed by his companions and others and found its way into the commercial mainstream.

The last decade 1981–1991

In 1980, Cicely Tyson returned to his life. He tried to reduce his drug use and to live more purposefully again. In April he began rehearsing with young Chicago musicians such as Robert Irving III , Darryl Jones and Vincent Wilburn . The first recordings for The Man with the Horn , his comeback album, which was released in 1981, were made in May . Davis eschewed effects devices as much as possible and played his trumpet again in a more traditional manner. The band, on the other hand, was more oriented towards pop music . He went on tour with Mike Stern , Marcus Miller (bass) and Bill Evans (saxophone) and others. However, his fellow musicians got pretty bad reviews, and overall the excitement for Miles Davis' new music was limited.

He married Cicely Tyson on November 27, 1981, but suffered a stroke in February 1982 that paralyzed his right hand for weeks. He treated himself with Chinese herbs and physiotherapy and was able to start the European tour in April. The 1982 live album We Want Miles , recorded in 1981, received very good reviews and was awarded a Grammy . In 1983 he was incapacitated for months by another hip operation and pneumonia , but returned to the stage in 1984. In the meantime, guitarist John Scofield , who was involved in the production of Star People (1983) and Decoy (1984), joined his band. Davis experimented with soul music and electronics on these albums . At that time Darryl Jones was playing in his band, who would later replace Bill Wyman with the Rolling Stones .

In 1985 You're Under Arrest was recorded, where he changed the style again. He played interpretations of two pop songs, Cyndi Lauper's Time After Time and Michael Jackson's Human Nature . For this he was criticized by jazz journalists, although the rest of the record was thoroughly praised. Der Spiegel even called it the "Louis Vuitton of electro-pop". Davis noted that many of the accepted jazz standards are just pop songs from Broadway pieces. You're Under Arrest was supposed to be Davis' last album for Columbia. Annoyed by the record company's demonstrative commitment to the young trumpet star Wynton Marsalis , who had criticized Miles Davis for his constant musical experiments and new approaches, and the simultaneous lack of interest in his own recordings, he switched to Warner Bros. He also played in 1985 in an episode of Miami Vice, the drug dealer and pimp Ivory Jones . He had another appearance as an actor in the Australian production Dingo from 1990, which appeared in theaters a year later. He contributed the soundtrack with Michel Legrand . Also in 1990 he worked on the soundtrack for The Hot Spot , a Dennis Hopper film starring Don Johnson . This soundtrack was heavily influenced by John Lee Hooker's blues guitar and style of music, but Miles Davis fit seamlessly into the musical concept.

The first album for Warner Brothers, Tutu (1986), featured synthesizers , samples and drum loops programmed for the first time on a Davis album . With the album Davis won his third Grammy in 1987 after Bitches Brew and We Want Miles .

Together with the band Toto , he recorded the track Don't Stop Me Now on the Fahrenheit album, also released in 1986 , which he enjoyed playing live. In 1988 he played a new version of his song Dune Mosse together with Zucchero in New York , which only appeared on Zucchero's album Zu & Co. in 2004 . In 1989 he divorced Cicely Tyson. In the same year his autobiography appeared , which he had written with Quincy Troupe . In it he gives information about his work and his influences. In January and February 1991 he went into the studio with hip-hop producer Easy Mo Bee , but before his death only six tracks were at least temporarily finished. The remaining pieces for the posthumously released album Doo-Bop were mixed by Easy Mo Bee from trumpet lines from unreleased studio sessions from the 1980s. Davis was thus involved in the development of jazz music in the last year of his life. On August 25, 1991, he played his last concert in Hollywood . The piece performed by Hannibal can be heard on the 1996 album Live Around the World .

In early September 1991, Davis underwent an examination at St. John's Hospital and Health Care Center in Santa Monica . During an argument with a doctor, he suffered a severe stroke and fell into a coma . On September 28th, his family decided to end the artificial life extension. AIDS rumors have never been verified. Miles Davis was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx , New York .

Significance and aftermath

Davis was an exceptionally prolific musician who released over a hundred albums in the 46 years of his career between 1944 and 1991 and played as a sideman on many more. Miles Davis is often seen as an innovator, sometimes also as a popularizer, of musical styles, to whom several creative periods such as the bebop, the cool jazz or the jazz-rock period can be ascribed.

On the evening of August 25, 1959, in front of the Birdland Club in New York City, he experienced firsthand racism and police brutality. One photo shows Miles Davis with a blood-splattered white shirt and a gash on his head. A policeman had hit him while he was talking to a white woman outside the club, smoking a cigarette with her and trying to take her to the taxi. This scene evidently provoked the police officer.

His career is often seen in connection with the civil rights movement of the 1960s, whose goals he also pursued as a black musician in the American music business. His Italian trumpeter colleague Enrico Rava , who has lived and worked in New York for a long time, said in an interview with Ekkehard Jost :

“Miles’s behavior as a black musician was revolutionary. I don't know if you heard that. But on all George Wein tours, the black musicians traveled in the second grade, while Stan Getz and Dave Brubeck traveled in the first grade. And everything went this way. And Miles was the first to really go against it ... I mean, what Miles was doing ... it was really important and really had great social significance. "

His self-confident appearance in public was a role model for many blacks at the time.

Miles Davis retired from the music business in the mid-1970s. After his return in the early 1980s, he experimented with various modern music styles such as hip-hop , pop music and rock. These years were also his most commercially successful years. In part, his creative power is attributed to the fact that, as a young musician, he had to realize that the previously successful bebop, as well as jazz in general, lost its appeal and audience to other music styles and thus the basis for his livelihood. This conflict spurred him on to enormous ingenuity.

Miles Davis the man

His fellow men saw him as a sensitive, changeable, sometimes unpleasant personality. His biographer Quincy Troupe described him as follows:

“Miles Davis was a volatile guy. One second he could be very charming and nice to be with, and the next second he could be the meanest guy you ever met […]. I experienced it with him. "

He cursed fellow musicians like Thelonious Monk as non- musicians or denigrated others like Clark Terry , Duke Ellington , Eric Dolphy or Jaki Byard in radio interviews; Prince he called a mixture of Jimi Hendrix and Charlie Chaplin . In concerts he often played with his back to the audience, which many concert-goers felt as a rejection. One reviewer wrote: “He seems to hate his audience as much as anyone can hate anyone. Then why is he playing for us? Does he just want our money? "

Miles Davis took a variety of psychoactive substances including heroin , alcohol , barbiturates, and cocaine . From the drugs he developed paranoid delusions and acoustic hallucinations . He also suffered from depression as a result of taking pain relievers for sickle cell anemia .

The jazz trumpeter

Trumpeter Miles Davis, who called Frank Sinatra a role model for his phrasing technique, has only a few constants in the course of his 46-year musician career. One of the constants is that he followed the advice of his first teacher all his life to refrain from vibrato . He played with a mouthpiece designed by Gustav Heim , a former principal trumpeter for the St. Louis Choral Symphony Society . From 1954 Davis used a Harmon mute with a removed stem insert to vary the timbre and pitch. The warm and full, sometimes delicate sound of his improvisations, for example on Seven Steps to Heaven , became Davis' trademark.

According to the critic Michael James "is (it) no exaggeration to say that never before in the history of jazz has the phenomenon of loneliness been examined so vividly as by Miles Davis". He later used electronic effects devices, especially the wah-wah.

While his importance as a band leader is undisputed, his trumpet style has been classified by some critics as limited, in some cases glaring technical flaws have been pointed out. Most critics and jazz fans, however, ignored the technical errors, overlooked them or only briefly addressed them.

“As a trumpeter Davis was far from virtuosic, but he made up for his technical limitations by emphasizing his strengths: his ear for ensemble sound, unique phrasing, and a distinctively fragile tone. He started moving away from speedy bop and toward something more introspective. His direction was defined by his collaboration with Gil Evans on the Birth of the Cool sessions in 1949 and early 1950 […]. ”

“As a trumpeter Davis was by no means virtuoso, but he compensated for his technical limitations by emphasizing his strengths: his ear for the ensemble's sound, unique phrasing and an unmistakably fragile tone. He began to move away from the fast bop towards something more inward. His direction was determined by his collaboration with Gil Evans in the Birth-of-the-Cool sessions in 1949 and early 1950 [...]. "

Miles Davis as a painter

In recent years Miles Davis devoted himself more and more to expressionist painting . At first he drew sketchy little line drawings and primitive figures in order to later experiment with bold colors and surreal motifs. The work of the Memphis Group in Milan had a strong influence on him. Later, his artwork was heavily inspired by the colors and motifs of African folk painting. He also painted numerous, slightly alienated self-portraits. Many of his drawings and pictures can be found on his record covers in the later years. In contrast to his extensive music education, he was self-taught in painting.

honors and awards

Miles Davis has received many honors and awards throughout his career. He was voted the best trumpet player by the readers of Down Beat magazine in 1955, 1957 and 1961. In 1962 he was elected to the Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame . In 2004, the year it was founded, he was inducted into the Ertegun Jazz Hall of Fame . The election into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2006 was met with incomprehension.

He received the Grammy Award nine times , including one for composing Sketches of Spain in 1961 . He received three Grammys for the band's best instrumental performance, one for the album Bitches Brew in 1970, one for the album Aura in 1989 and one for Miles & Quincy Live at Montreux in 1993. As a solo musician, he received four Grammys, for We Want Miles in 1982, for Tutu in 1986, for Aura in 1989 and posthumously in 1992 for Doo-Bop . He also received a Grammy for Lifetime Achievement in 1990.

In 1989 he was accepted into the Order of Malta . In 1990 he was inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame . On July 16, 1991 he was made a Knight of the Legion of Honor .

In 2015, listeners to the BBC and the British broadcaster Jazz FM voted him the most important jazz musician of all time from a selection of 50 musicians. The BBC presenter Geoffrey Smith said of the choice of Davis in front of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, in second and third place, that the immortals of jazz were gathered.

Movies

At the 2015 New York Film Festival , Don Cheadle presented his feature film Miles Ahead , in which Cheadle also played the lead role. The film is set at the end of the 1970s and does not see itself as a classic film biography , but lets Davis tell parts of his life and focuses on the music.

In 2019 the documentary Miles Davis - Birth of the Cool by Stanley Nelson was released.

Recordings (selection)

The following list tries to indicate the new direction in jazz that has emerged from today's perspective for special albums. It must be noted that with such subdivisions and terminology the boundaries are fluid.

To date, eight Miles Davis albums, Birth of the Cool, Bitches Brew, In a Silent Way, Kind of Blue, Miles Ahead, Milestones, Porgy and Bess and Sketches of Spain have been inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame .

collection

- Miles Davis & Gil Evans the Complete CBS Studio Recordings (1957-1968) . Mosaic , 1996 - 11 LPs with Ernie Royal , Bernie Glow , Taft Jordan , Johnny Carisi , Frank Rehak , Jimmy Cleveland , Willie Ruff , Lee Konitz , Danny Bank , Paul Chambers , Wynton Kelly , Johnny Coles , Gunther Schuller , Cannonball Adderley , Philly Joe Jones , Julius Watkins , Jimmy Cobb , Jerome Richardson , Elvin Jones , Harold Shorty Baker , Jay Jay Johnson , Steve Lacy , Wayne Shorter , Bob Dorough , Buddy Collette , Herbie Hancock , Ron Carter , Tony Williams , Howard Johnson , Hubert Laws

Remarks

- ^ In Miles Davis' biography, a German named Gustav is mentioned as a new high school music teacher who is believed to be Gustav Heim , a former principal trumpeter of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra; Davis also preferred to play with the mouthpiece developed by Gustav Heim and attributes this mouthpiece to his high school teacher Gustav in his biography . Heim joined the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1905 and died in 1933 when Davis was only seven years old. A contact from Davis to Gustav Heim or an apprenticeship with him is therefore unlikely.

- ↑ Eric Nisenson goes on to say that Betty Davis invited Jimi Hendrix to a party, at which Miles did not appear, but stayed in contact with Hendrix by phone and suggested a future collaboration that would never happen. See Nisenson: 'Round About Midnight. 1985, p. 166 f.

- ↑ Nisenson refers here to the previous collaboration between Miles Davis and Gil Evans , most recently in 1968 with the "Times of the Barracuda" project.

- ↑ We recommend that you play these recordings at the maximum volume possible to fully appreciate the sound of Miles Davis.

literature

- Ian Carr : Miles Davis. A critical biography. LIT, Baden 1982, ISBN 3-906700-02-X .

- Jack Chambers: Milestones 1. The Music and Times of Miles Davis to 1960. Milestones 2. The Music and Times of Miles Davis Since 1960. Beech Tree Books, William Morrow, New York 1983 and 1985 (Volume 2).

- Bill Cole: Miles Davis. A Musical Biography. William Morrow & Company, New York 1974.

- George Cole: The Last Miles - The Music of Miles Davis, 1980-1991 . University of Michigan Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-472-03260-0 .

- Miles Davis, Quincy Troupe: Miles Davis. The autobiography. Heyne, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-453-17177-2 .

- Ashley Kahn : Kind of blue. The making of a masterpiece. Rogner & Bernhard at Zweiausendeins, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-8077-0176-1 .

- Franz Kerschbaumer : Miles Davis. Style-critical investigations into the musical development of his personal style. Academic Printing and Publishing Establishment, Graz 1978, ISBN 3-201-01071-5 .

- Jörg Konrad: Miles Davis. The story of his music. Bärenreiter Verlag, Kassel 2009, ISBN 978-3-7618-1818-3 .

- Tobias Lehmkuhl : Coolness. About Miles Davis. Rogner & Bernhard at Zweiausendeins, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8077-1048-8 .

- Jan Lohmann: The Sound of Miles Davis. The discography. 1945-1991 . JazzMedia ApS, Copenhagen 1992, ISBN 87-88043-12-6 .

- Eric Nisenson: 'Round About Midnight. A portrait by Miles Davis. Hannibal, Vienna 1985, ISBN 3-85445-021-4 .

- Eric Nisenson: The Making of Kind of Blue, Miles Davis and His Masterpiece. St. Martin's Press, New York 2000.

- Wolfgang Sandner : Miles Davis. A biography. Rowohlt Berlin, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-87134-677-4 .

- Paul Tingen: Miles Beyond. The Electric Explorations of Miles Davis, 1967-1991. Billboard Books, New York 2001.

- Keith Waters: The Studio Recordings of the Miles Davis Quintet, 1965-68 , Oxford Studies in Recorded Jazz, Oxford UP 2011

- Peter Niklas Wilson : Miles Davis. His life, his music, his records. Oreos, Waakirchen 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 .

DVD

- Mike Dibb: The Miles Davis Story. The definitive look at the man and his music (DVD, English with German subtitles).

- Michael Lerner: Another Bitches Brew. Miles Davis at the Isle of Wight Festival (DVD, multilingual).

Web links

- Literature by and about Miles Davis in the catalog of the German National Library

- Biography and bibliography ( memento of January 11, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) from the Darmstadt Jazz Institute

- Largest German Miles Davis website with extensive discography

Individual evidence

- ^ John Fordham : 50 great moments in jazz: How Miles Davis plugged in and transformed jazz ... all over again (2010) at The Guardian

- ↑ Jason Parker: House of Representatives Affirms Miles Davis' "Kind Of Blue" as National Treasure. Does This Ring Hollow To Anyone Else? (No longer available online.) In: One Working Musician. December 16, 2009, archived from the original on October 16, 2014 ; accessed on October 11, 2014 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ A b John F. Szwed: So What: The life of Miles Davis . William Heinemann, 2002, ISBN 0-434-00759-5 , pp. 15-16.

- ^ Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , p. 9.

- ^ John F. Szwed: So What: The life of Miles Davis . William Heinemann, 2002, ISBN 0-434-00759-5 , p. 19.

- ^ John F. Szwed: So What: The life of Miles Davis . William Heinemann, 2002, ISBN 0-434-00759-5 , pp. 25-26.

- ↑ Miles Davis, Quincy Troupe: Miles Davis. The autobiography. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1989, ISBN 3-455-08357-9 , p. 55.

- ^ A b Miles Davis, Quincy Troupe: Miles Davis. The autobiography. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg, 1990, ISBN 3-455-08357-9 , pp. 70-72.

- ↑ Miles Davis, Quincy Troupe: Miles Davis. The autobiography. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1990, ISBN 3-455-08357-9 , p. 63.

- ^ A b c Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , pp. 11-13.

- ↑ Miles Davis, Quincy Troupe: Miles Davis. The autobiography. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg, 1990, ISBN 3-455-08357-9 , p. 88.

- ^ Jörg Konrad: Miles Davis. The story of his music. Bärenreiter Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-7618-1818-3 , pp. 16-18.

- ↑ Stephen Thomas Erlewine: Miles Davis. Birth of the Cool. In: allmusic.com. Retrieved October 4, 2014 .

- ^ A b c d e Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , pp. 14-15.

- ^ A b c d Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , pp. 16-18.

- ^ A b Jörg Konrad: Miles Davis. The story of his music. Bärenreiter Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-7618-1818-3 , pp. 48-53.

- ^ Jörg Konrad: Miles Davis. The story of his music. Bärenreiter Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-7618-1818-3 , p. 51.

- ↑ Miles Davis, Quincy Troupe: Miles Davis. The autobiography. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg, 1990, ISBN 3-455-08357-9 , p. 248.

- ^ Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , pp. 141-142.

- ↑ Miles Davis, Quincy Troupe: Miles Davis. The autobiography. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg, 1990, ISBN 3-455-08357-9 , p. 251.

- ^ Jörg Konrad: Miles Davis. The story of his music. Bärenreiter Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-7618-1818-3 , pp. 143-144.

- ^ Jörg Konrad: Miles Davis. The story of his music. Bärenreiter Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-7618-1818-3 , pp. 144-146.

- ↑ Miles Davis, Quincy Troupe: Miles Davis. The autobiography. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg, 1990, ISBN 3-455-08357-9 , pp. 274-278.

- ↑ Miles Davis, Quincy Troupe: Miles Davis. The autobiography. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg, 1990, ISBN 3-455-08357-9 , p. 282.

- ^ John F. Szwed: So What: The life of Miles Davis . William Heinemann, 2002, ISBN 0-434-00759-5 , p. 173.

- ^ Ashley Kahn: Miles Davis: The Complete Illustrated History. Voyageur Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-7603-4262-6 , p. 106.

- ↑ Kind Of Blue: Legacy Edition. ( Memento from November 15, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ) on the Miles Davis website

- ↑ 500 Greatest Albums of All Time: 12. Miles Davis, 'Kind of Blue'. In: Rolling Stone. May 24, 2012, accessed April 14, 2014 .

- ^ Richard Cook: It's About That Time: Miles Davis on and Off Record. Oxford Univ. Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-532266-8 , p. 130.

- ↑ Gerald Early, Clark Terry: Miles Davis and American Culture. Univ. of Missouri Press, 2001, ISBN 1-883982-38-3 , p. 43.

- ^ A b Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , pp. 23-24.

- ↑ a b c d e f Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , pp. 24-26.

- ^ Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , pp. 25-26.

- ^ Scott Yanow: Jazz on Record: The First Sixty Years. Backbeat Books, 2003, ISBN 0-87930-755-2 , p. 569.

- ^ A b c d Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , pp. 28-29.

- ↑ homas Winkler: Black Madonna. In: Spiegel online. June 21, 2007, accessed May 14, 2016.

- ^ Nisenson: 'Round About Midnight. 1985, p. 158.

- ^ A b c d Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , pp. 28-29.

- ↑ Quoted from Nisenson: 'Round About Midnight. 1985, p. 163.

- ↑ Quoted from Peter Wießmüller: Miles Davis. His life, his music, his records. Oreos, Waakirchen 1990, ISBN 3-923657-04-8 , p. 154.

- ↑ Jazz innovator Miles Davis: Always miles ahead. In: Spiegel online. Retrieved September 28, 2016 .

- ↑ Paul Tingen: The Making of In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew. In: miles-beyond.com. 2001, accessed November 4, 2014 .

- ^ Ashley Kahn: Miles Davis: The Complete Illustrated History. Voyageur Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-7603-4262-6 , p. 216.

- ^ Ashley Kahn: Miles Davis: The Complete Illustrated History. Voyageur Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-7603-4262-6 , p. 150.

- ^ Jörg Konrad: Miles Davis. The story of his music. Bärenreiter Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-7618-1818-3 , p. 128.

- ^ Joslyn Layne: Circle Biography. In: allmusic.com. Retrieved November 8, 2014 .

- ↑ Fred Jung: A Fireside Chat with Michael Henderson. In: allaboutjazz.com. December 15, 2003, accessed November 8, 2014 .

- ^ Jörg Konrad: Miles Davis. The story of his music. Bärenreiter Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-7618-1818-3 , pp. 134-135.

- ^ Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , p. 30.

- ^ The Wire's "100 Records That Set The World On Fire (While No One Was Listening) + extra 30 Records". In: discogs.com. Retrieved November 9, 2014 .

- ^ A b Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , pp. 30-31.

- ^ Jörg Konrad: Miles Davis. The story of his music. Bärenreiter Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-7618-1818-3 , p. 139.

- ↑ Vladimir Bogdanov: All Music Guide to Jazz: The Definitive Guide to Jazz Music. Backbeat Books, 2002, ISBN 0-87930-717-X , p. 306.

- ^ Jörg Konrad: Miles Davis. The story of his music. Bärenreiter Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-7618-1818-3 , p. 144.

- ^ Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , pp. 31-32.

- ↑ Miles Davis, Quincy Troupe: Miles Davis. The autobiography. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1989, ISBN 3-455-08357-9 , pp. 399-400.

- ^ A b c d Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , pp. 32-33.

- ↑ Jürg Laederach: Elevator to Success . In: Der Spiegel . No. 41 , 1991 ( online ).

- ↑ George Cole: The Last Miles: The Music of Miles Davis 1980-1991. Equinox Publishing, London 2005, ISBN 1-84553-122-1 , p. 154.

- ↑ Miami Vice: Season 2, Episode 6, Junk Love (Nov. 8, 1985) in the Internet Movie Database .

- ^ Dingo (1991) in the Internet Movie Database (English).

- ↑ Gerald Early, Clark Terry: Miles Davis and American Culture. Univ. of Missouri Press, 2001, ISBN 1-883982-38-3 , p. 222.

- ↑ George Cole: George Cole - Steve Lukather about Miles Davis . In: The Last Miles: The Music of Miles Davis 1980-1991 . Equinox Publishing, London 2006, ISBN 1-84553-122-1 ( stevelukather.com [accessed November 9, 2014]).

- ^ A b Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , pp. 34-35.

- ^ A b c d Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , p. 36.

- ^ A b c d Gerald Early, Clark Terry: Miles Davis and American Culture. Univ. of Missouri Press, 2001, ISBN 1-883982-38-3 , pp. 3-4.

- ↑ Harald Kisiedu in conversation with Andreas Müller: From the civil rights movement to “Black Lives Matter”; How jazz became a mouthpiece against racism. June 24, 2020, accessed August 4, 2020 .

- ^ Ekkehard Jost : Jazz musician. Materials on the sociology of African-American music. Ullstein Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / Berlin / Vienna 1982, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Gerald Early, Clark Terry: Miles Davis and American Culture. Univ. of Missouri Press, 2001, ISBN 1-883982-38-3 , p. 112.

- ↑ Jeff Niesel: Acclaimed Poet Quincy Troupe to Give Lecture on Miles Davis. In: clevescene.com. October 3, 2014, accessed January 4, 2015 .

- ↑ a b c Joachim-Ernst Behrendt: The Jazz Book. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1999, ISBN 3-596-10515-3 , pp. 142-143.

- ↑ Nick Joyce: The Return of a Reckless One. In: bazonline.ch. October 8, 2014, accessed December 21, 2014 .

- ↑ Joachim-Ernst Behrendt: The Jazz Book . Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1999, ISBN 3-596-10515-3 , p. 147.

- ^ A b c G. I. Wills: Forty lives in the bebop business: mental health in a group of eminent jazz musicians. In: The British Journal of Psychiatry. 183, 2003, pp. 255-259, doi: 10.1192 / bjp.183.3.255 .

- ^ A b c Peter Niklas Wilson: Miles Davis. His life. His music. His records. Oreos Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-923657-62-5 , p. 61.

- ^ Gustav F. Heim (1879–1933). 2009, accessed December 29, 2014 .

- ↑ Joachim-Ernst Behrendt: The Jazz Book . Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1999, ISBN 3-596-10515-3 , p. 136.

- ^ A b Robert Walser: Out of Notes: Signification, Interpretation, and the Problem of Miles Davis. In: The Musical Quarterly. Vol. 77, No. 2 (Summer, 1993), pp. 343-365.

- ↑ Jim Macnie: Miles Davis - Biography. In: Rollingstone.com. Retrieved October 19, 2014 .

- ^ Wolfgang Stock: Miles Davis as a painter. Stockpress.de, April 11, 2011; Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ↑ Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: "Pissfleck" scolding from the Sex Pistols. In: Spiegel online. March 14, 2006, accessed November 8, 2014 .

- ^ A b c d William Ruhlmann: Miles Davis. In: allmusic.com. Retrieved November 9, 2014 .

- ↑ St. Louis Walk of Fame - Miles Davis. In: stlouiswalkoffame.org. Retrieved November 9, 2014 .

- ^ Miles Davis voted greatest jazz artist . BBC News, November 15, 2015, accessed November 16, 2015.

- ↑ Nigel M Smith: Miles Ahead: Don Cheadle on doing Miles Davis justice on screen . In: The Guardian . October 10, 2015, accessed November 16, 2015.

- ^ Grammy Hall of Fame. Grammy Foundation website; Retrieved July 27, 2012.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Davis, Miles |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Davis III, Miles Dewey |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American jazz trumpeter, piano horn player, composer and band leader |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 26, 1926 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Alton , Illinois |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 28, 1991 |

| Place of death | Santa Monica |