Battle of Wimpfen

| date | April 26, 1622 Jul. = May 6, 1622 greg. |

|---|---|

| place | south of Bad Wimpfen |

| output | Catholic victory |

| consequences | since 1594, managed by the line of Baden-Durlach Markgrafschaft Baden-Baden is again the line Baden-Baden Baden awarded the house by the emperor and thus the upper Badische occupation ended |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 21,000 | 2 500 cavalry 9 700 infantry 300 artillery 12 500 total |

| losses | |

|

450 dead, |

600 dead |

The Battle of Wimpfen on May 6, 1622 was an important battle in the first phase of the Thirty Years' War , the Bohemian-Palatinate War . It was beaten between Wimpfen , Biberach , Obereisesheim and Untereisesheim and ended with the victory of the Catholic, Bavarian and Spanish troops under Tilly and Córdoba over the Lutheran margrave Georg Friedrich von Baden-Durlach .

history

Elevation of the troops

Tilly had lost the battle at Mingolsheim on April 27 and withdrew with his 15,000-strong Catholic army across the Kraichgau in the direction of the Neckar crossing at Wimpfen . The almost 70,000 strong Protestant army initially followed Tilly's troops, but then separated at Schwaigern . Mansfeld moved to the North Palatinate, the Baden Margrave Georg Friedrich held 13,000 men, according to other sources there were 20,000, still in touch with Tilly's Catholic troops, who plundered the country on their way. On May 5th, the Baden troops moved from Schwaigern via Kirchhausen and Biberach, which was plundered by Tilly, in the direction of Wimpfen to attack the Catholic troops there.

On the evening of May 5, 1622, the Baden army, coming from the south-west, crossed the flood-leading Böllinger Bach near Obereisesheim and stood in battle order over a front length of around 2 kilometers: the infantry in the Heilbronner Klinge , the cavalry on the Rosenberg and the guns at the vineyards of the Böllinger Hof . Tilly's troops took up positions north of it in and around the Obereisesheimer Dornetwald . The western wing was formed by the Spanish troops under Córdoba. Tilly's headquarters were in the Cornelienkirche in Wimpfen , not far from where he had the Altenberg ski jump built. A painting in the Dominican Church in Wimpfen , which was Tilly's arsenal, shows the general in prayer in front of the Seated Madonna , who was then still in the Cornelienkirche , while the battle is already raging in the background.

The first outpost skirmishes took place in the evening, but they subsided when it got dark.

Course of the battle

In the early morning of May 6, 1622, Tilly's artillery opened the battle. The superior Baden artillery responded and was unsuccessfully attacked by Bavarian cavalry as it was thrown back by the Margrave's cavalry. The battles for mutual attrition lasted until around 11 a.m. Córdoba was still holding back, because the Catholic-League side still expected that Mansfeld's army could intervene in the battle behind them. Margrave Georg Friedrich, on the other hand, was not aware of the presence of Córdoba's troops, and he bet on waiting for Tilly to attack his strong wagon castle. Both sides initially lacked the will to attack vigorously and the fighting came to a standstill. Reports that Tilly formally requested a ceasefire have not been confirmed. In any case, there was no significant fighting between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. While Tilly's associations recovered, the Margrave regrouped his units during this time.

In the early afternoon Tilly's troops surprisingly attacked the right wing of the margrave, whose Lorraine horsemen then fled towards Neckargartach . At about 5.30 p.m. a cannon hit in the open powder car of the margrave's troops exploded their ammunition dump. Part of the margraves' army panicked and fled, which enabled Tilly's troops to advance further and further south and east. Around 6 p.m., Duke Magnus von Württemberg fell , who had led his cuirassier regiment on the side of the margrave. Shortly afterwards, Tilly's troops succeeded in taking the margraves' wagons and their guns. At around 8 p.m., the margravial crew from Obereisesheim surrendered. The local population had fled across the Neckar in the afternoon.

The defeated margrave troops, which were besieged by Tilly from the north and west, were enclosed in the east by the Neckar and in the south by the swollen Böllinger Bach. The margrave, presumably confident in his own victory, had not considered an escape route for his troops. Only a single bridge at the Böllinger mill led over the Böllinger Bach, in front of which the fleeing people jammed and were overtaken and massacred by Tilly's cavalry. According to some sources, by the evening there should have been a total of around 5,000 deaths, including around 4,000 on the battlefield and 600 in the surrounding area.

After their victory, the league troops devastated Obereisesheim and killed the residents who had not been able to escape. The Spaniards under Córdoba moved into quarters near Neckargartach and devastated it. Since the residents of Obereisesheim had fled, the thousands of fallen soldiers on the battlefield were not buried until May 12th and 17th, 1622 by people from the nearby imperial city of Heilbronn .

Tilly and Córdoba tried in the further course of the Bohemian-Palatinate War to prevent the unification of the remaining Protestant armies under Mansfeld and Christian von Halberstadt . Halberstadt was captured on June 20 in the battle of Höchst and badly beaten.

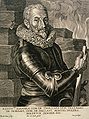

Johann t'Serclaes von Tilly, engraving by Pieter de Jode the Elder. Ä. after Anthony van Dyck

The parties

Troops of the Electoral Palatinate

For Frederick V of the Palatinate , only the troops raised and recruited by Georg Friedrich were involved in the battle, the armies of Mansfeld and Christian of Braunschweig could not intervene.

On the one hand, Georg Friedrich had mobilized Landwehr regiments from his dominion. The regiment recruited from the Baden Unterland was referred to as the White Regiment , and the Pforzheim contingent also belonged to it, around which heroic legends were based in the tradition.

On the other hand, there were also mercenary associations recruited outside Baden among the margrave's troops. Wilhelm and Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar brought two regiments to them, and so did Duke Magnus of Württemberg . These mercenaries were u. a. recruited in Thuringia, Westphalia, Lorraine and Switzerland.

Georg Friedrich had equipped his troops with an extraordinarily powerful artillery consisting of around 40 guns of different sizes. In the Turkish Wars, the imperial army had carried many armored wagons with them to protect them against rapid attacks by horsemen, which both offered protection during marches and could be assembled to form wagon castles. Georg Friedrich also wanted to use this defensive tactic and carried around 70 so-called spit wagons with him. These very agile chariots were armed with iron spikes (hence the name) to deter enemy cavalry. The wagons were armed with small swiveling howitzers .

The entourage consisted of 1,800 wagons which, in addition to provisions and ammunition, also transported siege equipment and even a ship's bridge.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Reitzenstein, p. 191 rather suspects an accident caused by “careless handling of loose powder”.

- ↑ These Landwehr regiments comprised mostly foreign mercenaries who had reported at the advertising space in Baden, the local portion had not been drawn, but consisted of subjects who were also recruited. The term Frei Fähnlein is also used for them.

- ↑ s. Pflüger, p. 382

literature

- Gerhard Taddey (ed.): Lexicon of German history . Events, institutions, people. From the beginning to the surrender in 1945. 3rd, revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-520-81303-3 , p. 1368.

- Karl Freiherr von Reitzenstein: The campaign of 1622 on the Upper Rhine and in Westphalia up to the battle of Wimpfen. 2 booklets, Munich 1891/93, booklet 2, pp. 151-202 in the Internet Archive

- Moriz Gmelin : Contributions to the history of the Battle of Wimpfen . Braun, Karlsruhe 1880 ( at archive.org ).

- Wilhelm Kühlmann: The Battle of Wimpfen (1622) and the death of Duke Magnus von Württemberg (1594-1622) on horseback . In: S. Thomas Rahn / Hole Rößler (eds.): Media Fantasy and Media Reflection in the Early Modern Age. Festschrift for Jörg Jochen Berns, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz 2018 (Wolfenbütteler Forschungen; 157), ISBN 978-3-447-11139-3 , pp. 159–181.

- Ernst Münch, Ernst Ludwig Posselt: Memories of the battle at Wimpfen and the death of the four hundred Pforzheimer , Freiburg 1824 in the Google book search

- JGF Pflüger: History of the City of Pforzheim , Pforzheim 1861, pp. 380–394 in the Google book search

- Karl du Jarrys Freiherr von La Roche : The Battle of Wimpfen on April 26th / 6th May 1622. In: Journal for Art, Science and the History of War, year 1846, Seventh Booklet, pp. 48–91 online at the Saxon State Library - Dresden State and University Library

- Karl du Jarrys Freiherr von La Roche : The Battle of Wimpfen on April 26th / 6th May 1622 (supplements). In: Journal for Art, Science and the History of War, year 1846, Eighth Booklet, pp. 143–164 online at the Saxon State Library - Dresden State and University Library

Historical drama

- Ernst Ludwig Deimling: The four hundred Pforzheimer citizens or the battle near Wimpfen , Karlsruhe 1788 in the Google book search

Web links

- Files in the General State Archives Baden-Württemberg

- Historical map from 1627: Outline of the battle, for example between Margrave von Durlach and Monsieur Tylli, as Kays. and Bavarian Generaln processes ( digitized )

Coordinates: 49 ° 11 ′ 50 ″ N , 9 ° 10 ′ 20 ″ E