Battle of Nördlingen

| date | 5th and 6th September 1634 |

|---|---|

| place | Noerdlingen , Bavaria |

| output | Victory of the Imperial-Bavarian-Spanish troops, Catholic side |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Ferdinand of Spain , Ferdinand King of Hungary , Elector Maximilian of Bavaria |

|

| Troop strength | |

| 16,020 infantrymen, 9,260 cavalrymen, 42 cannons | 29,500 infantrymen, 19,450 cavalrymen, 32 cannons |

| losses | |

|

8,000 dead or wounded, 3,000 prisoners |

1,200 dead and about as many wounded |

The two-day battle at Nördlingen was one of the main battles of the Thirty Years War , which took place on August 26th . / 5th September 1634 greg. began and between two Swedish armies under the leadership of the generals Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar and Gustaf Horn and three allied armies under the leadership of the Supreme Commander of the Imperial Army Archduke Ferdinand , King of Hungary, the Cardinal Infante Ferdinand of Spain as the commander of a Spanish army and the Elector of Bayern Maximilian as commander of the Bavarian Army of the Catholic League was discharged. After the Swedish King Gustav Adolf was killed in the Battle of Lützen in November 1632 , the collapse of Swedish power in the Thirty Years' War was sealed by the total defeat of the Swedes in the Battle of Nördlingen. The outcome of the battle had far-reaching territorial and strategic consequences, led to new alliances, the Peace of Prague and the active entry of France into the war on the side of the weakened Swedes.

Overview

The battle of Nördlingen began a good month after the two Swedish armies involved in the battle failed to prevent the city of Regensburg from being recaptured by an Imperial Bavarian army. The failure of the two Swedish generals Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar and Gustaf Horn had ended with the arduous march from Regensburg back to the vicinity of Nördlingen . After that, the Swedish armies were decimated and exhausted.

In contrast, the imperial Bavarian army, which was successful near Regensburg, led by Archduke Ferdinand King of Hungary , later Emperor Ferdinand III, was able to begin the siege of Nördlingen and was additionally reinforced by Spanish troops led by Cardinal Infante Ferdinand of Spain . On the Swedish side, they had to wait for reinforcements in the camp near Bopfingen , which did not arrive.

Attempts by the Swedes to break the siege of Nördlingen were unsuccessful and then led to what was one of the few battles in the Thirty Years War that lasted over two days. After initial success, the Swedish attack was broken off at midnight on September 5, 1634 and continued on the morning of September 6. Loss of time on the approach, disagreements between the Swedish generals and the resulting strategic errors, the strong fighting power of the Spanish troops, but also unfortunate coincidences and, first and foremost, the numerical superiority of the troops on the Catholic side, which the Swedish commanders greatly underestimated, led to an overwhelming victory of the Catholic allies over the Swedes and their Protestant German allies.

The victory not only cost the Swedes the almost complete loss of the two armies involved with all their equipment, but also led to the territorial loss of southern Germany and the Franks. After their defeat, the Swedes also lost their allied Electoral Saxony , which concluded the Peace of Prague with the emperor the following year . The conclusion of this partial peace without taking Swedish interests into account led to the entry of France into the war on the side of the Swedes and to the bloodiest chapter of the Thirty Years' War.

The two months before the battle

In July 1634 two Swedish armies with Field Marshal Gustaf Horn and Duke Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar set out in Augsburg to end the siege of the city of Regensburg, which was occupied by Swedish troops, by an imperial Bavarian army. A lack of information about the threatening situation in Regensburg and the different strategic ideas of the two Swedish generals led to time being lost on the approach. When the Swedes set out to march on on July 30th after conquering Landshut and plundering for several days, they learned shortly before reaching Regensburg that the city had already surrendered on July 26th, 1634 and the Swedish occupation troops with commander Lars Kagg had withdrawn.

The new commander-in-chief of the Imperial Army, King of Hungary Archduke Ferdinand , had achieved his first major military success with the reconquest of Regensburg and had already marched off with large parts of the Imperial Bavarian Army on July 21st to reach Württemberg via Ingolstadt and the Nördlinger Ries reach. There they wanted to unite with the advancing Spanish army under Cardinal Infante Ferdinand of Spain in order to drive the Swedes from the Rhine.

The Swedish army was now also forced to march back to the west in order to prevent the planned merger of the enemy armies. The return march took place in heavy rain and was extremely arduous. On August 6th the Swedish armies reached Augsburg completely exhausted and with great losses of material, horses and men. It was clear to the commanders that both “ruined armies” needed a longer break. So the conquest of the previous Swedish district town Donauwörth by the imperial Bavarian army on August 16 could not be prevented. On August 18, imperial-Bavarian troops began the siege of Nördlingen . The town, to which the surrounding population had fled, was defended by 400 Swedish mercenaries and 600 city soldiers.

Duke Bernhard and Field Marshal Horn were surprised by the rapid advance of the enemy troops, but also learned that parts of the army had withdrawn to Franconia and Württemberg, plundered the areas that were only poorly protected by Sweden and hindered the approach of reinforcements. On August 23, both Swedish armies gathered near Bopfingen - 12 km west of Nördlingen - with a strength of approx. 20,000 men. About 4,000 men were expected to come from Franconia under the command of Johann Philipp Cratz von Scharffenstein , but they did not arrive until September 5th, the first day of the battle. The corps of Rhine Count Otto Ludwig von Salm-Kyrburg-Mörchingen , which was also expected and estimated at 5,000 men , was delayed and arrived on the second day of the battle, when the Swedes had already lost the battle.

The expected Spanish army had moved across the Brenner, Innsbruck and Munich and crossed the Lech on August 23 at Rain. In the besieged Nördlingen there had been 1,400 deaths by that day. At the request of residents and refugees in Nördlingen, the Swedish troops began attacks on the imperial-Bavarian siege troops on August 24th. Success was achieved, but in the end the Swedish troops withdrew, which disappointed the city's defenders. The reason for the termination were different assessments of the two Swedish commanders about the chances of success of a stronger operation. At this point in time there was no battle - as Duke Bernhard wanted - although the Swedish troops were not as numerically inferior to the Imperial Bavarian troops as they were a few days later after the arrival of the Spanish army was.

After further violent shelling of Nördlingen, the city was on the verge of collapse when the Spanish army arrived on September 3. On September 4th, there was a main attack by Bavarian troops on the breaches in the wall in the city wall of Nördlingen between Berger and Reimlinger Tor . The defenders were able to repel seven attacks with difficulty. At the end of the day, in the Swedish camp near Bopfingen, the decision was made to take stronger measures against the siege troops in order to prevent the threatened conquest of the city. In order to be able to wait for the expected reinforcements to arrive at the same time, the commanders Gustaf Horn and Duke Bernhard had agreed on a defensive strategy. The strategy was not to start a great battle immediately, but to present the army ready to attack in a non-vulnerable position to the enemy. The main army was to occupy an elevated position on the Arnsberg near the Ohrengipfel on the edge of the Nördlinger Ries . From there you could see everything up to Nördlingen and supplies for your own army were also secured. For the hostile Imperial-Bavarian-Spanish army, supplies were not secured, and therefore a threatening situation would arise for this large army, which would at least force the withdrawal of the Spanish army, while the Swedish side could wait for the expected reinforcements to arrive.

Course of the battle

The first day of the battle

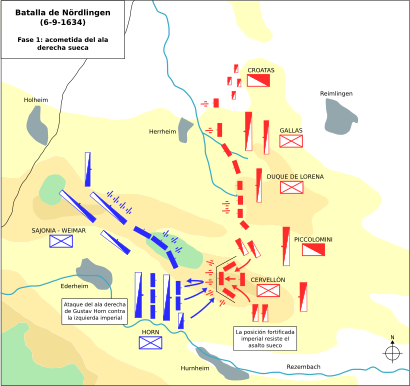

The Swedish army set out on the morning of September 5th. For the approach, a route was chosen via Dehlingen , 8 km south of Bopfingen, from there in a north-easterly direction along the road to Ulm and shielded by a ridge, the camp of the enemy troops on the elevated Schönefeld - approx. 7 km south of Nördlingen - to approach. The vanguard and the main army under Duke Bernhard followed a route without inclines and met outposts of the Imperial Spanish Army in the afternoon between Ederheim and Holheim . The surprising appearance of the Swedish troops was reported to their commanders on Schönefeld - approx. 4 km east of Ederheim. Supported by the hastily launched attacks by the cavalry, Imperial Spanish troops managed to occupy the two prominent elevations west of the army camp on the plain between the rivers Eger and Rezenbach with around 500 infantry each before the Swedish troops set foot there could grasp. The enemy armies were separated by these two closely adjacent elevations - the unwooded, rocky Albuch hill and the forested Heselberg - and these two elevations were therefore strategically important.

Subsequently, cavalry battles supported by light artillery and musketeers developed, in which up to 6,000 horsemen were involved on both sides. By 6 p.m. in the evening, the Swedish troops managed to gain a foothold in the plain northwest of Albuch and Heselwald and secure the elevated positions of Lachberg, Himmelreich and Ländle by advancing foot troops. The successes achieved quickly and unexpectedly under the sole command of Duke Bernhard created a situation that did not fit the defensive strategy agreed between Horn and Duke Bernhard. Field Marshal Horn and his troops had not even arrived on the battlefield at that time and Duke Bernhard had pursued an attack strategy that he expanded at the end of the day. Before sunset, with the support of light artillery, Swedish attacks began with around 4,000 foot soldiers on the wooded Heselberg, which at that time, like the neighboring Albuch hill, was only occupied by weak Spanish forces. After the Swedish attacks began, the weak forces were reinforced several times and later also supported by Spanish soldiers under the command of General of the Artillery Don Giovanni Maria Serbelloni on the neighboring Albuch. The resistance was so strong that Duke Bernhard's troops could not fully occupy Heselberg until midnight.

At midnight, the troops led by Horn arrived on the battlefield with the rearguard and heavy artillery. The approach on an eastern route over the Arnsberg at the Ohrengipfel had been delayed because order had been lost on the descent into the valley of the Rezenbach between Ederheim and Hürnheim. The cavalry, foot soldiers, and artillery were in utter disarray and hindered each other. After reaching the battlefield, because of the darkness, the units could no longer intervene in the fighting over the Heselberg, which had already subsided, and the neighboring Albuch hill could no longer be attacked.

In view of the situation that had arisen, the defensive strategy was no longer relevant and both commanders envisaged storming the Albuch hill for the next day. Even the interrogation of the captured Spanish officer Escobar could not dissuade them from that. The interrogation revealed that the strength of the Spanish army with 14,000 foot soldiers and 3,500 riders should have been assessed. These statements were correct, but were met with disbelief by Duke Bernhard. He estimated the Spanish troops at 5,000 foot soldiers and 2,000 cavalrymen and thus drastically underestimated the strength of the Spanish troops by 10,000 men.

The latest investigations into the total number of troops involved in the battle show for the Swedish side: 16,020 infantry and 9,260 cavalry, totaling approx. 25,300 men. For the Catholic, Imperial-Bavarian-Spanish side: approx. 29,500 infantry and approx. 19,450 cavalry, totaling approx. 50,000 men. Even if one takes into account the uncertainties in the numbers of the Catholic troops, the result is a figure of around 42,000 men. This results in a majority of the Catholic troops of approx. 11,000 men or a ratio of 1 Swedish soldier to 1.7 soldiers on the Catholic side.

The second day of the battle

Nocturnal preparations and formation of the troops

After the Swedish attacks were stopped, Spanish troops used the rest of the night to fortify the rocky Albuch hill with three crescent-shaped entrenchments protected by earthen walls so that the commanders considered it possible to hold the hill against the expected Swedish attacks. After the loss of the Heselberg, the Spaniards were so depressed that the generals Archduke Ferdinand and Ferdinand of Spain decided for the Habsburgs and Charles IV (Lorraine) for Bavaria to equip the entrenchments with guns, to strengthen the crews with provided cavalry, to position some Spanish reserve units behind the Albuch hill and to place all troops on the Albuch with a total of 5,400 infantry and 2,700 riders under the command of Matthias Gallas . On the Swedish side, both generals underestimated not only the number of enemy troops, but also the extent and effectiveness of the defensive structures built by the Spaniards on the Albuch at night.

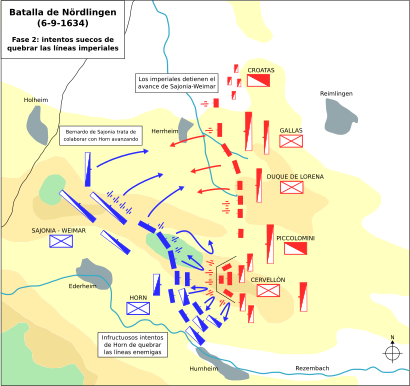

The fighting resumed at 5 a.m. The main aim of the Swedish attack was to conquer the strategically important Albuch hill. The three entrenchments built there were manned by 3,900 infantry from all three armies on the Catholic side, reinforced by 2,700 horsemen and 14 guns. As a reserve, 1,500 infantry from a Spanish Tercios under the command of Don Martin de Idiaques y Camarena were positioned north behind the Albuch . A total of 8,100 men were available, about 1/5 of the entire army. In addition, 6,000 reserve troops were available in the army camp on Schönefeld.

The Swedish troops planned for the attack on the right wing under the command of Field Marshal Horn stood south in front of the Albuch hill, in the west beginning at Heselberg with 5,020 infantry, then continued east with 4,850 riders. In total, with 9,700 men, about 1/3 of the entire army were available and thus a number similar to that on the enemy side. It should be noted, however, that attacks on elevated, fortified positions had to be expected with considerable losses, which could hardly be covered by the weak Swedish reserves, while the defenders had many reserves at their disposal. On the left Swedish wing stood Duke Bernhard's troops, beginning in the west at Holheim with 4,400 men in 10 regiments of cavalry under Taupadel , Cratz , Duke Ernst von Sachsen Weimar and other commanders. Then 3,150 infantry men with riders, distributed over the northern slope of the Lachberg to the northern slope of the Heselberg and in the Heselwald itself. Altogether, with 7,550 men, a little less than 1/3 of the total army were available.

Duke Bernhard's infantry had the task of holding Heselberg, which had been conquered the day before, and from there to support the attacks of Horn's troops on the neighboring Albuch. The cavalry was supposed to threaten the enemy troops set up about 1 km north of about 5,000 horsemen under the command of Isolani , Maximilian von Billehe and Johann von Werth and about 8,000 infantry under Gallas , Piccolomini and Don Giovanni Maria Serbelloni so that they could not intervene in the attacks of the Horn troops on the Albuch. The Swedish generals did not realize that these troops, with a total of 13,000 men, were almost twice as strong as the troops that Duke Bernhard had at his disposal.

Swedish attack on the middle Albuch-Schanze 5 - 8 o'clock

The start of the attack on the Albuch was delayed because Lieutenant Colonel Witzleben , the commander of Field Marshal Horn's body regiment , misinterpreted a scouting ride by Horn at the foot of the Albuch hill as the start of the attack. The body regiment left its position, was embroiled in a cavalry battle and pushed so far that Horn was only able to free his body regiment from the predicament with considerable losses.

After the troops were again deployed, the delayed attack on the middle Albuch-Schanze took place, carried out by the Scottish brigade under the command of Colonel William Gunn , supported by the Johann Vitzthum von Eckstädt brigade , which had already been significantly involved in the conquest of Heselberg the day before. During the attack, the inexperienced Bavarian regiment of Lieutenant Colonel Wurmser was completely wiped out in the central hill, which was equipped with guns. The successful attack led to the expulsion of the defenders of the hill and to the capture of the guns, but then by an unfortunate coincidence it became a defeat for the attackers when a powder explosion occurred in the already captured hill. The Swedish troops lost their order and were driven out of the redoubt by an immediate flank attack by Spanish cavalry. Horn had neglected to secure the infantry attack with his own cavalry and he did not succeed in reoccupying the briefly unoccupied hill with infantry troops that were quickly following up.

Instead, the jump was re-occupied by a Spanish Tercio from the reserve with approx. 1500 men under Don Martin Idiaquez y Camarena who was quickly commanded . This quick reaction of the Spanish troops proved to be decisive for the further course of the battle for the Albuch hill. Field Marshal Horn's troops did not succeed in another 15 attacks until around noon to conquer the middle hill from the war- experienced Spanish troops who fought with the fire tactics of the peloton fire and with downhill counter-attacks. Even supporting the attacks by deploying the cavalry against the northern rear of the Albuch did not lead to the success of the infantry attacks on the southern side. All attacks by the Swedish cavalry were countered by the opposing side, with a large cavalry battle developing in the middle of the mountain plateau, which was decided before 8 a.m. by the massive intervention of the imperial and Bavarian cavalry to the disadvantage of the Swedes.

Fights on the north side of the Albuch, 8-10 a.m.

When the focus of the fighting had shifted to the north side of the Albuch and an unfortunate situation for the Swedes arose there, Duke Bernhard commanded the infantry brigade under Colonel Johann Jacob von Thurn with 1,600 battle-hardened veterans there, around the northern Albuch-Schanze, which was run by Hispanic-Neapolitan troops under GaspareToraldo de Aragon was defended to attack. The first attack began very successfully, but was slowed down by Spanish reinforcements quickly brought in with 1,300 musketeers. The attack stalled and ended with a retreat of the Thurn Brigade to the northern edge of the Heselwald in order to prevent enemy troops advancing into the strategically important position. When the Thurn Brigade was attacked by cavalry there and even the Swedish cannons positioned there were lost, Horn tried to provide support through the use of his body regiment. Duke Bernhard had also started attacks with his cavalry on the left wing around 8 o'clock in order to tie up the enemy cavalry facing him. All attempts at support were in vain. The exhausted and decimated Thurn Brigade had to be withdrawn and replaced by less experienced and already ailing troops. This was the turning point of the fighting, because now the initiative had finally passed to the Spanish side. This was solely due to the growing majority of Spanish troops north of the Albuch from an initial 900 men at 5 a.m. to 5,200 men at 10 a.m.

Burglary of Spanish-Imperial-Bavarian troops in the Heselwald, 10 a.m. - 12 p.m.

Reinforced by Bavarian infantry and imperial cuirassier regiments, the majority of Spanish troops conquered the Swedish positions on the northern edge of the Heselwald and began to follow the retreating Swedish troops on the Heselberg from the north and also from the neighboring Albuch and gradually back down into the Heselwald to bring their possessions. The infantry von Horn could no longer prevent this threat, which was dangerous for Duke Bernhard's troops at the foot of the Heselwald, because after 15 unsuccessful assaults on the Albuch by 12 noon, his troops were severely decimated and completely exhausted. Field Marshal Horn now decided to break off the fight and, in consultation with Duke Bernhard, begin an orderly retreat. The plan envisaged that Duke Bernhard and his foot troops should hold the artillery positions on the Lachberg and the Ländle and keep the enemy in check with his cavalry until Horn his troops with the artillery in the plain of the Rezenbach to the west Direction to Ederheim would have led to reach from there the Arnsberg with the ear summit. Then Duke Bernhard's troops should have started their retreat on the Arnsberg under the protection of Horn's artillery.

Fight on the Swedish left flank, 8 a.m. - 12 p.m.

At 8 o'clock in the morning the dragoon regiments Taupadel and Cratz tried on the left Swedish wing to ride around the Bavarian cavalry opposite them at the village of Herkheim 1 km away under the command of Werth and Billehe and to attack in the flank. The maneuver failed and a cavalry battle ensued, initially with varying successes in which the Bavarian commander Billehe was killed. But when General Gallas sent two imperial cuirassier regiments to reinforce, the entire Swedish cavalry was pushed back about 1 km to the south to the Ländle and the south-sloping slopes of Lachberg and Heselwald. Wanted than the posted there Musketiereinheiten Swedish support the retreating Swedish cavalry, many of the soldiers were from the imperial cuirassiers massacred . During the strong counterattack of the Imperial Bavarian cavalry, battles of the infantry had also started on the plain north between Heselberg and Herkheim. Duke Bernhard had ordered infantry units there to take action against the imperial positions near Herkheim. There, too, the Swedish attack was brought to a standstill and the numerically superior imperial cavalry began to drive the Swedes back. Duke Bernhard was now forced to retreat with all infantry units to the starting positions at the foot of the Heselberg in order to protect the left flank of Field Marshal Horn's troops there under the protection of the artillery on Lachberg and Ländle, which were in vain until 12 noon Continue attacks on the Albuch. After the Swedish cavalry had regrouped at the foot of the Heselberg, Duke Bernhard made the plan to advance with the cavalry over a narrow pass between Heselberg and Lachberg against the imperial positions at Herkheim. Without his knowledge, the pass had been occupied by the Imperial Dragoon Regiment under Colonel Butler . The first attempts by the Swedish cavalry to use the pass were repulsed. In order to be able to hold the pass, Butler immediately requested reinforcements, which he received immediately, consisting of 500 Croatian horsemen, 300 musketeers and five regiments of cuirassiers. Nevertheless, Duke Bernhard made further, increasingly desperate attempts to free the pass through his cavalry, supported by musketeers. All attempts were unsuccessful, claimed many victims and weakened his troops so much that advancing Bavarian foot troops even managed to conquer the Lachberg and use the Swedish artillery located there against the Swedes themselves. Already at this time, while Duke Bernhard's troops were trying in vain to dominate the pass, the withdrawal of the exhausted troops from the Albuch, which Field Marshal Horn had agreed with Duke Bernhard, had started as planned on the Swedes' right wing. Imperial Spanish regiments under Gallas and Leganes , as well as Piccolomini's cuirassiers used this critical phase to follow the withdrawing Swedish regiments over the eastern flank of the Albuch, which had already been abandoned by the Swedes, while the Imperial Croatian cavalry fell in the rear of the Swedish entourage that had already withdrawn.

Duke Bernhard's troops collapse and escape

On the Lachberg, conquered by Bavarian troops, the local commander, Duke Karl, had also recognized that Field Marshal Horn's troops were beginning to withdraw. He immediately ordered all available cavalry regiments and also two imperial cuirassier regiments under Gonzaga to attack the Swedish brigades of Duke Bernhard in front of the Heselwald. From the western flank of the Albuch, Spanish infantry regiments and cuirassiers under Serbelloni advanced, firing peletons, against the positions of the Swedish infantry regiments, which began to lose order under the onslaught. When the Bavarian cavalry broke into the ranks of the foot regiments, Duke Bernhard's body regiment was almost completely destroyed and order completely collapsed. The Swedish infantry troops began to flee and could no longer be stopped by Duke Bernhard, who waved the flag of his body regiment. The Swedish cavalry, permanently attacked by the Bavarian cavalry, fled back towards Ederheim over the slopes of Lachberg and Ländle. In the Rezenbachtal the fleeing cavalry collided with the troops of Field Marshal Horn, who were still in an orderly retreat. Despite several attempts by Horn to maintain order, a chaotic escape of all Swedish troops now developed. The refugees on foot were pursued by Croatian and Bavarian horsemen and many of them were killed and looted. For the mounted refugees, the Swedish troops of Rheingraf Otto Ludwig von Salm-Kyrburg-Mörchingen , who had long been expected as reinforcements , were found only a few kilometers from the site of the battle, a godsend. Duke Bernhard also fled on horseback. His horse was shot and he got into a fight with some Croatians, from which he was freed by three of his soldiers. He luckily escaped captivity when an officer from the Taupadel regiment gave him a horse. With Field Marshal Horn and many other officers, a total of around 4,000 Swedes were taken prisoner.

losses

The number of dead and wounded exceeded all previous numbers in the battles of war. Among the Swedes, the number of dead and wounded - most of whom also died - was 8,000, while on the Catholic side the number was 1,200. The material losses suffered by the Swedes were enormous. The entire artillery with 42 guns, 80 wagons with ammunition and 180 quintals of powder was lost. The entire entourage with 3,000 baggage carts, the entire war chancellery and the till were lost.

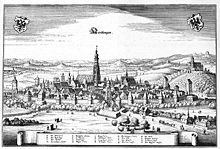

Merian stitch: Depiction of the battle line-up and the fight near Nördlingen

Legend text Merian stitch

| symbol | Legends text | Legend text (with explanation) included |

|---|---|---|

| A. | The Arnsberg | The Arnsberg (with ear summit) |

| B. | Skirmishes between some regiments | First skirmish on September 5th |

| C. | Swedish suit | Suit (approach) of the Swedish |

| D. | Forest where she posed | Heselberg or Heselwald |

| E. | Mountain where some Spanish settled in the wood | Albuch hill (with entrenchment) |

| F. | Post under the mountain where the Swedish stood | Rentzenbachtal |

| G | Dorff Hirnheim | Dorff Hirnheim (error in the legend text, correct is: Dorf Edernheim) |

| H | Escape of the Swedish Reutereyen behind the Arensberg | Escape from the Swedish Reuterey |

| I. | Swedish lincer grand piano under Duke Bernhard | left wing of the Swedes |

| K | Croats looting the baggage | Croats |

| L. | Hill over the Croaten | Himmelreich (hill) |

| M. | Swedish so want to throw themselves in Nördlingen | Information is missing |

| N | Imperial Reuterey which drives the same back | Information is missing |

| O | King of Hungary and Cardinal Infantry | King of Hungary and Cardinal Infantry |

| P | Duke of Lorraine | Duke of Lorraine |

| Q | Johann von Wert | Johann von Werth |

| R. | Imperial and Spanish Reuterey | Imperial and Spanish Reuterey |

| S. | Assembly point of the Imperial and Spanish armies before the meeting | Information is missing |

| T | Imperial pieces and batteries | Imperial batteries |

| V | Imperial camp | Information is missing |

| X | Spanish warehouse | Information is missing |

| Y | Duke Bernhard of Weimar | Duke Bernhard |

| Z | Field Marshal Gustav Horn | Field Marshal Horn |

| + | Spanish cavalry and foot = people | Information is missing |

| 1 | Swedish yellow brigades | Swedish yellow brigades |

| 2 | Counts of Thurn Brigades | Counts of Thurn Brigades |

| 3 | Duke Bernhard's Brigades | Duke Bernhard's Brigades |

| 4th | Gustav Horn's brigades | Gustav Horn's brigades |

| 5 | The Scots | The Scots |

| 6th | Obersten Pfuhl's Brigades | Obersten Pfuhl's Brigades |

| 7th | Württemberg Brigades | Württemberg Brigades |

| 8th | Colonel Ranzau Brigades | Colonel Ranzau Brigades |

| 9 | Duke Bernhard's body regiment | Duke Bernhard's body regiment |

| 10 | Gustav-Horn's body regiment | Gustav Horn's body regiment |

| 11 | Colonel Oxenstiern's regiment | Colonel Oxenstirn's regiment |

| 12 | General-Major Rossstein's regiment | General-Major Roßstein |

| 13 | Hofkirchen Regiment | Hofkirchen |

| 14th | Major Goldstein | Major Goldstein |

| 15th | Count Cratz | Count Cratz |

| 16 | Lieutenant Colonel Birckenfeld | Lieutenant Colonel Birckenfeld |

| 17th | Brandenstein | Brandenstein |

| 18th | Beckermann | Beckermann |

| 19th | Courville | Courville |

| 20th | Duke Ernst | Duke Ernst |

| 21st | Margrave of Brandenburg | Margrave of Brandenburg |

| 22nd | Colonel Former | Former |

| 23 | Supreme Tupadel's Regiment | Tupadel |

| 24 | Lieutenant General Count Gallas | Count Gallas |

| 25th | Marquis of Leganes Spanish general | Marquis of Leganes |

| 26th | General Serbelloni | General Serbelloni |

| 27 | Prince Piccolomini | Prince Piccolomini |

| 28 | Neapolitan Reuterey | Neapolitan Reuterey |

| 29 | Supreme Lesli Regiment | Supreme Lesli Regiment |

| 30th | Wurmisch and Salmisch Regiment | Wurmisch and Salmisch Regiment |

| 31 | Caspar Toralto Neapolitan | Caspar Toralto Neapolitan |

| 32 | Lombard regiment | Lombard regiment |

| 33 | Imperial German foot = Volck | Imperial German infantry |

| 34 | Prince S. Severino, Neapolitan Regiment | Prince S. Severino, Neapolitan |

| 35 | Marquis Torrecusa Regiment Neapolitans | Marquis Torrecusa Regiment Neapolitans |

| 36 | Burgundian regiment | Burgundy |

| 37 | Marquis Lunato Regiment, Lombardy | Marquis Lunato Lombards |

| 38 | Count Fuenclara Regiment, Spaniard | Count Fuenclara, Spaniard |

| 39 | Imperial and Ligist Volck | Imperial and Ligist Volck |

| 40 | Approved after the city | Addressed to the city (Nördlingen) |

| 41 | King in Hungary 2 body regiments | King in Hungary body regiments |

| 42 | Cardinal Infanten Compagnie | Cardinals-Infanten Leib-Compagnie |

Reasons and speculation about the defeat of the Swedes

Divergent interests and demoralization in the run-up to the battle

- Just as the heavy defeat of the Catholic side in the Battle of Breitenfeld was preceded by the dismissal of Wallenstein because of the diverging interests of the Catholic princes, so the heavy defeat of the Protestant side in the battle of Nördlingen was the fragmentation (" change ") of the Swedish army preceded by half a dozen occupying armies with diverging interests of their commanders. The Heilbronner Bund , which was supposed to bring the Swedes together with the Protestant imperial princes, remained a torso.

- The two commanders on the Protestant side, Duke Bernhard and Field Marshal Horn, rarely agreed. On the other hand, on the Catholic side, after the murder of Wallenstein with Archduke Ferdinand, King of Hungary , they faced a commander-in-chief who had succeeded in uniting not only the Catholic League , which was dominated by Bavaria, with the imperial army into one powerful army, but also Spain and to induce his cousin, the Spanish Cardinal Infante, to intervene directly in the Imperial War. Planning and implementation of the joint campaign with three armies were a novelty and Archduke Ferdinand had thus initiated something that Wallenstein had never achieved or never wanted.

- The Catholic side with Archduke Ferdinand had brilliantly passed the acid test of the new alliance on July 26, 1634 with the recapture of Regensburg. The subsequent rapid march of the Catholic troops to Württemberg and the union there with the Spanish army, in a region that the Swedes viewed as their safe haven, surprised and demoralized the Swedes. The Catholic side had had very successful weeks militarily, while the two Swedish generals, after the unsuccessful relief of Regensburg and the loss-making march back, had to rely on reinforcements on their arrival in Augsburg, which then arrived slowly or not at all. From August 18, the exhausted Swedish armies were confronted with the siege of Nördlingen , a city that Duke Bernhard had promised protection and to which he was therefore obliged. Since the Swedish attempts to terrorize the city were unsuccessful, the attempt to start a great battle offered a way out which Duke Bernhard was ready to go, even if there was news that should have made him doubt.

Doubtful and failed strategic planning in advance of the battle

- The usual characterizations of Field Marshal Gustaf Horn as the cautious strategist and of Duke Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar as the impulsive daredevil cannot explain the course of the battle. Whether the early attack proposed by Duke Bernhard would have been successful before the arrival of the Spanish army remains speculative, especially since the Swedish army was badly hit after the march back from Regensburg. The chance of victory against a numerically similarly strong opponent - before the arrival of the Spanish army - would have been greater, especially since the battle showed that after the first success, the intervention of the Spanish troops in the battle for the Albuch entrenchments was decisive for the failure of all further Swedish attacks.

- After the decision to start a battle had been made, the defensive strategy considered by Horn and Duke Bernhard with a defensive initial phase of waiting, observing and threatening would have been successful with a high degree of probability. The supply problems of the great Imperial-Spanish-Bavarian army would have forced the withdrawal of at least the Spanish army after 10 days and during this time the expected Swedish reinforcements would have arrived.

Strategic mistakes and mishaps during battle

- An early attack on the still unfortified Albuch on the first day of the battle was neglected because the troops from Horn did not arrive before midnight because of the disorder that had occurred during the unsuccessful approach.

- Left on his own, Duke Bernhard pursued an unexpectedly successful attack strategy on the first day of the battle, which after the late arrival of the von Horn troops made it no longer opportune to pursue the defensive strategy originally envisaged. The cause of this wrong decision was, in addition to the underestimation of the effectiveness of the fortifications built by Spanish experts in a short time on the Albuch, first and foremost the massive underestimation of the huge numerical superiority of the Catholic side, despite the information available. The majority and the good overview of Matthias Gallas as the military commander-in-chief of the Catholic side meant that imperial, Bavarian or Spanish troops could be sent from the reserves to endangered combat sectors at any time in order to gain the upper hand there.

- The premature first attack by Field Marshal Horn's body regiment on the Albuch, based on a misunderstanding, led to delays and losses.

- After the successful conquest of the middle Albuch-Schanze during the first attack, there was no support from the cavalry to hold the hill against imperial cavalry attacks. This strategic mistake was compounded by the mishap of a powder explosion in the ski jump, which led to a chaotic escape for the Swedish conquerors of the ski jump. This made it possible for Spanish troops to quickly occupy the abandoned hill again with experienced troops.

- When Field Marshal Horn decided to retreat after all the Swedish attacks on the Albuch had failed, there was insufficient agreement between the two commanders on the timing and extent of the agreed cover measures during this critical phase. At the beginning of the withdrawal of the Horn troops, Duke Bernhard made senseless attempts to break through to the imperial positions near Herkheim in a strategically and topographically unfavorable location at all costs, instead of occupying his own positions in front of the Heselwald and thus closing Horn's left flank to back up. "It is difficult to explain the heroism or recklessness with which Duke Bernhard rushed to attack the imperial troops".

Medal for the Battle of Nördlingen, Army History Museum , Vienna.

Consequences of the defeat of the Swedes

The Swedish defeat at Nördlingen had effects that went far beyond the effects of previous battles in the war. As a direct consequence of the defeat, the three imperial districts , the Swabian District , the Franconian District , and the Bavarian District , as well as large parts of the Austrian Imperial District and more than 40 imperial cities and five fortresses, came under Imperial Bavarian control through subsequent conquests or surrenders. With the exception of the high fortresses Hohentwiel , Hohenurach and Hohenasperg , the city of Nördlingen and then all other cities, including Stuttgart and Heilbronn, were quickly taken. Only Schorndorf was able to hold out under the Swedish Colonel Taupadel until December 15, 1634. Even Upper Swabia , which had been at war with the Swedes for two years , came under imperial power again within a short time.

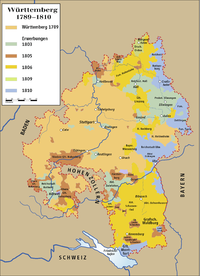

In the Duchy of Württemberg - what was then Altwuerttemberg - the rural population was particularly affected, because this territory was chosen as winter quarters for the imperial Bavarian troops after the withdrawal of the Spanish army. Duke Eberhard III. had fled with the court into exile in Strasbourg , as did Duke Julius Friedrich from the Württemberg-Weitlingen line . The country was defenseless at the mercy of the wandering soldiers. Whole areas - especially the Swabian Alb - were plundered and devastated. After Emperor Ferdinand II learned of the victory of his troops, he gave away large areas of Württemberg to relatives and favorites. In accordance with the Edict of Restitution , the monasteries were again occupied by monks and re-Catholicized. Only in the Peace of Westphalia was the Duke of Württemberg reinstated in all his rights.

Another momentous measure was the dissolution of the Franconian Duchy, which was formed by King Gustav Adolf in November 1631 from the territories of the two monasteries of Würzburg and Bamberg and which was transferred to the Duchy of Franconia of Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar after the king's death .

As the most important indirect consequence of the defeat, the Swedes lost their most important ally, the Protestant Elector Johann Georg I of Electoral Saxony . He graduated in May 1635 with the Catholic Emperor Ferdinand II. The Peace of Prague . Many Protestant imperial estates followed within a few months, as did the important imperial cities of Augsburg (after siege and surrender), Nuremberg , Frankfurt and Memmingen . In September 1635, France finally entered the war alongside the Swedes, who had been weakened by the defeat. The bloodiest chapter of the Thirty Years' War began with the Swedish-French War .

Monuments

Since it was erected in 1896, a memorial stone on the Albuch hill has commemorated the battle. It was built by the Beautification Association Nördlingen (VVN) and is only a few meters away from the Otto-Rehlen-Hütte, built in 1935 (named after the then local group chairman of the Swabian Alb Association ). A replica of the engraving by Matthäus Merian was attached to the memorial stone in 2009.

literature

- Lothar Höbelt: From Nördlingen to Jankau. Imperial strategy and warfare 1634–1645. Heeresgeschichtliches Museum, Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-902551-73-3 .

- Axel Stolch: Erhard Deibitz. City commander in Nördlingen and Frankfurt am Main. A picture of life in the Thirty Years War. Steinmeier, Deiningen 2010, ISBN 978-3-936363-48-7 .

- A. Stolch, J. Wöllper: The Swedes on the Breitwang. A contribution to the history of the city of Bopfingen and the battle of Nördlingen in 1634. Heimat- und Fachverlag F. Steinmeier, Nördlingen 2009.

- Peter Engerisser, Pavel Hrnčiřík: Nördlingen 1634. The battle of Nördlingen - turning point of the Thirty Years' War. Verlag H. Späthling, Weißenstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-926621-78-8 .

- Decision in Swabia. In: Geo epoch. 29, 2008 ( The Thirty Years War )

- Peace nourishes, war and strife destroyed. 14 contributions to the battle of Nördlingen in 1634. (= Yearbooks of the Historical Association for Nördlingen and the Ries. 27). Nordlingen 1985.

- Cicely Veronica Wedgwood: The Thirty Years War. Paul List-Verlag, Munich 1967.

- Karl Jakob: From Lützen to Nördlingen. Ed. van Hauten, Strasbourg 1904, pp. 65-66.

- Walter Struck: The battle near Nördlingen in 1634. A contribution to the history of the Thirty Years War. With an overview card and a map of Nördlingen and the surrounding area. Publishing house of the Royal Government Printing House, Stralsund 1893. (digitized version)

- Oscar Fraas : The Battle of Nördlingen on August 27, 1634. Beck, Nördlingen 1869.

- Heinrich Christoph von Grießheim (Griesheim): Happy main Victoria and true relation like the same to the most revered ChurFürsten and Mr. H. Archbishop of Mainz / from the Adelichen Raht / and Amptman to Fritzalr / Christoff Heinrichen from Grießheim / about the royal Mayst. on Hungary and Bäheim / on the sixth ... September 1634 Bey Nördlingen again the Swedish ... received ... Victori ... was performed. Cologne 1634, (VD17 12.125523 A), BSB catalog Bavar 5117

Web links

- Detailed texts and material on the battle of Nördlingen at www.anno1634.de

- The Battle of Nördlingen / The Swedes on the Breitwang

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Peter Engerisser, Pavel Hrnčiřík: Nördlingen 1634. The battle of Nördlingen - turning point of the Thirty Years' War. Verlag Späthling, Weißenstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-926621-78-8 , pp. 77-97.

- ↑ a b c Peter Engerisser, Pavel Hrnčiřík: Nördlingen 1634. 2009, pp. 97-108.

- ↑ a b c d Peter Engerisser, Pavel Hrnčiřík: Nördlingen 1634. 2009, pp. 109–130.

- ↑ Peter Engerisser, Pavel Hrnčiřík: Nördlingen 1634. 2009, p. 289.

- ^ Lothar Höbelt: From Nördlingen to Jankau. Imperial strategy and warfare 1634-1645. Heeresgeschichtliches Museum, Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-902551-73-3 , p. 21, footnote 17.

- ↑ Peter Engerisser, Pavel Hrnčiřík: Nördlingen 1634. 2009, pp. 185, 190, 287.

- ↑ Peter Engerisser, Pavel Hrnčiřík: Nördlingen 1634. 2009, ill. P. 169, p. 252.

- ↑ Peter Engerisser, Pavel Hrnčiřík: Nördlingen 1634. 2009, ill. P. 169, p. 131, 253, 254.

- ↑ a b c d e Peter Engerisser, Pavel Hrnčiřík: Nördlingen 1634. 2009, pp. 131–141.

- ↑ Peter Engerisser, Pavel Hrnčiřík: Nördlingen 1634. 2009, p. 134.

- ↑ Peter Engerisser, Pavel Hrnčiřík: Nördlingen 1634. 2009, pp. 270, 272.

- ↑ Peter Engerisser, Pavel Hrnčiřík: Nördlingen 1634. 2009, pp. 144 f, 268, 269.

- ↑ Peter Engerisser, Pavel Hrnčiřík: Nördlingen 1634. 2009, pp. 138, 139.

- ↑ a b c Lothar Höbelt: From Nördlingen to Jankau. 2016, pp. 14–19.

- ↑ Ricarda Huch: The Thirty Years War. 2nd volume (= Insel Taschenbuch. 23). 1st edition. 1974, pp. 814-816.

- ↑ Ricarda Huch: The Thirty Years War. 2nd volume (= Insel Taschenbuch. 23). 1st edition. 1974, pp. 818-821.

- ↑ a b c Peter Engerisser, Pavel Hrnčiřík: Nördlingen 1634. 2009, pp. 155–158.

- ↑ a b c Peter Engerisser, Pavel Hrnčiřík: Nördlingen 1634. 2009, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Wilfried Sponsel: The refuge on the Albuch. In: Augsburger Allgemeine. August 24, 2009. Retrieved September 24, 2017 .

- ↑ Wilfried Sponsel: Memorial of the great battle. In: Augsburger Allgemeine. August 24, 2009. Retrieved September 24, 2017 .

Coordinates: 48 ° 48 ′ 18.1 ″ N , 10 ° 29 ′ 34.1 ″ E