Battle of the Alte Veste

| date | August 24th July / September 3, 1632 greg. until August 25th jul. / 4th September 1632 greg. |

|---|---|

| place | Old fortress near Zirndorf |

| output | Imperial victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 28,000 | 27,000 |

| losses | |

|

1,200 dead, |

300 dead, |

In the Battle of the Alte Veste (also the Battle of Fürth , the Battle of Zirndorf or the Battle of Nuremberg ), the imperial general Albrecht von Wallenstein and a Swedish army under Gustav Adolf met in the Thirty Years' War at the beginning of September 1632 without a decisive victory for either side succeeded.

prehistory

The Protestant armies, led by Christian IV. And Ernst von Mansfeld , suffered devastating defeats in 1626, the Protestant cause seemed lost. Gustav II Adolf of Sweden, however, saw the chance to enforce his hegemonic claims in north-eastern Europe after Denmark left. The “Lion from Midnight” landed on Usedom with a relatively small army of 13,000 men on July 6, 1630, went from victory to victory and, above all, defeated Tilly on September 17, 1631 in the battle of Breitenfeld (north of Leipzig): “ Freedom of belief for the world, saved at Breitenfeld - Gustav Adolf, Christian and hero. ”Gustav Adolf penetrated further and further south of the Holy Roman Empire . Tilly, still in Erlangen on March 27, 1632 , initially evaded.

Gustav Adolf in Nuremberg and Fürth

At the beginning of the Thirty Years' War, Nuremberg found itself on a tightrope walk between traditionally loyal to the emperor's policy and membership of the Protestant religious party. From 1619 to 1631 Nuremberg came under the imperial sphere of influence, but - allegedly under duress - joined the King of Sweden politically on November 2, 1631 and later on March 31, 1632 also militarily. In March 1632 Gustav Adolf camped for the first time on the Hardhöhe near Fürth , only to move into Nuremberg on March 31st. From there he set out with the army and defeated on 14/15. April for the second time after the Battle of Breitenfeld (1631) the numerically superior army of Tilly in the Battle of Rain am Lech . Tilly was hit so badly in the right thigh by a falconet bullet during the battle that he succumbed to his injuries on April 30th in Ingolstadt .

After this victory, Gustav Adolf began his march to Bavaria. Although he refrained from conquering Ingolstadt and Regensburg , he moved into Munich in May 1632 . The Emperor's court in Vienna now feared a threat to Austria.

In view of the Swedish successes, Emperor Ferdinand II reactivated Wallenstein (actually: Albrecht Wenzel Eusebius von Waldstein), who had been dismissed in 1630 . Wallenstein intended to prevent the threatened advance of the Swedes into Austria by threatening the important base of Nuremberg in the rear of the Swedes by setting up an army camp and thus also endangering the routes of retreat of Gustav Adolf. Gustav Adolf recognized the danger, turned to the north again and moved with parts of his army (around 18,000 men) from Old Bavaria to Fürth. The troops took shelter in the "open field", probably again on the Hardhöhe and Gustav Adolf stayed from June 17 to 19, 1632 in the Fürth rectory on Kirchenplatz (at least the maintenance deliveries from Nuremberg are addressed there). To prevent the approaching Bavarian army from uniting with Wallenstein's troops, Gustav Adolf moved to Vilseck via Nuremberg . The union of the two armies was still successful, but did not bring military success because the soldiers of the Bavarian army were so weakened that many of them died. On July 3rd Gustav Adolf was back in Nuremberg. His army took camps in the southwest outside Nuremberg and Gustav Adolf had the city's fortification belt expanded.

Wallenstein's camp

Wallenstein left Prague on June 4, 1632. On the way to Neustadt an der Waldnaab , he united with the Bavarian Army, reached today's city limits of Fürth on July 17th and had a huge camp built in the area of today's district towns of Zirndorf , Oberasbach and Stein , for which a good 13,000 trees were felled . 31,000 infantrymen, 12,000 horsemen and a convoy of unknown size, but a total of around 60,000 people and (initially) 15,000 horses camped there for 70 days. This was the largest encampment in world history. Wallenstein recognized that, despite his numerical superiority, it was not advisable to attack Gustav Adolf in his “fortifications” around Nuremberg. However, he managed to put a blockade ring around Gustav Adolf's army, so that the latter ran into supply difficulties. The previously undefeated king was fixed for six weeks and condemned to inaction.

Relief for Gustav Adolf

The first aid armies for the outnumbered King of Sweden advanced on August 21 against Fürth , where a smaller division of imperial soldiers was meanwhile. After a two-hour outpost battle in the area between Vach and Fürth, the imperial family withdrew to Wallenstein's camp, and the auxiliary army marched through Fürth to the camp of Gustav Adolf. Above all, the Swedish relief army of Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna achieved a breakthrough with 24,000 men on August 27, and he then passed over (Erlangen-) Bruck to the Swedish king. Oxenstierna reported on "a small patch called Fürtt ... with a small fortification", which is interesting in that nothing is otherwise known of Fürth's fortifications.

Swedish attack in the Nuremberg / Gebersdorf area

After the arrival of the relief armies on August 31, 1632, King Gustav Adolf offered Wallenstein the great field battle on the site to the left and right of today's Rothenburger Strasse, but Wallenstein did not agree to it. On September 1, Gustav Adolf fired three batteries at the Wallenstein camp in the Gebersdorf area - without much success. A Swedish infantry attack on Wallenstein's camp at 5 p.m. on the Fernabrücke (from today's bus junction “Fürth-Süd”) did not succeed. Gustav Adolf broke it off, marched from 10 p.m. along today's Schwabacher Strasse to Fürth, probably built one or more temporary bridges (probably between today's Max and Siebenbogen bridges, i.e. in the area of the bank promenade), crossed the Rednitz at night and built a fortified one Camp on the Fürth Hardhöhe , which was continuously expanded even after the battle until the withdrawal on September 18th. The camp wall extended from the Rednitz along the Hardstrasse over the Kieselbühl to (possibly) to Unterfarrnbach; According to historical maps, the town of Fürth itself (at that time the extension included the old town quarter around the town church of St. Michael ) was enclosed by the wall.

Due to this north-west movement, Wallenstein wrongly suspected a bypass attack from the west and on September 2 and in the night of September 3 brought the majority of his troops into battle formation on the western side of his camp (on the western edge of Zirndorf).

Gustav Adolf, however, was looking for the field battle in the Heilstättensiedlung / Eschenau area, and perhaps he wanted to attack Wallenstein's camp from the outset - this can no longer be fully clarified - but on its northeast side.

The "Battle of the Alte Veste" (Swedish attack from Fürth)

In the early morning of September 3, 1632, the Swedish army advanced from the Hardhöhe, took up battle formation at 7 a.m. in three wings in the fields in front of today's city forest between Unterfürberg and Dambach and began at 9 a.m. on a battle line of 2.7 Kilometers the attack. Gustav Adolf personally led the left wing near Dambach. Initially, however, nothing of Wallenstein's army was to be seen, which is why Gustav Adolf falsely suspected that Wallenstein was about to withdraw. They wanted to use that and rush into the supposed trigger, so the Swedes were careless. The king sent a large part of the cavalry in the direction of Schwabach and Neumarkt in order to disrupt Wallenstein's withdrawal, which in reality stood in full battle order on the west side of the camp (today's western outskirts of Zirndorf) and waited there for the Swedes. Gustav Adolf then attacked Wallenstein's camp on its strongest side - due to the natural environment - which Wallenstein had not expected, but which Gustav Adolf himself later described as “donkey”.

Right wing fails on Rosenberg

The Swedes fought their way up on their right wing from today's Eschenau over the Rosenberg and took an artillery jump (still visible today in remnants) at today's Zirndorfer water reservoir, where they prepared their own artillery positions 250 meters from the edge of the camp. However, it was not possible to bring heavy artillery over the Rosenberg. The edge of the camp was reinforced by Wallenstein with 3000 musketeers in the course of the afternoon and could not be taken without heavy artillery.

Center remains in front of the old fortress

The center and parts of the Swedish left wing - including a Scottish regiment - unsuccessfully attacked the ruins of the Old Veste , which was located outside the camp, heavily entrenched and armed with artillery . The Alte Veste, built around 1230, was partially destroyed by the Nuremberg people in 1388, since it belonged to the enemy of the Nuremberg burgrave at the time, but it was still usable as a bastion. The artillery ramp to the castle ruins, which was laid out in 1632, has been preserved and is now used as a staircase to the observation tower. The forest had been removed by Wallenstein's troops to create a free field of fire, which was successful, and flank attacks by Bavarian cavalry and Croatian horsemen brought the attack by the Swedes to a halt, although the attack was "with great furia". Contemporary witnesses reported: "Mountain and forest were nothing but smoke and steam".

Left wing reaches bearing fixture

Gustav Adolf was now looking for the decision on the left wing. The actual camp boundary of Wallenstein ran along Sonnenstrasse ( Zirndorf ) to project east of the connecting road to the north. In front of that there was a defensive line on the Fuggerstrasse line and, in its connection - above the current intersection of Kellerweg / Südwesttangente - a Sternschanze equipped with artillery . Remnants are said to have been left at the former “Schuhs Keller” restaurant until the autobahn was built. Covered by a battery at today's Dambacher Erlöserkirche, the Swedes attacked these positions under the leadership of Gustav Adolf. Bavarian elite dragoons fended off the attack, but were in turn pushed back by Finnish tank riders who had been standing by at the Dambacher Bridge until then. Further flank attacks 500 Fuggerian cuirassiers came into the fire of 700 Swedish musketeers, where Colonel Jakob Graf Fugger (1606-1632) was hit. Gustav Adolf gave him wine from his canteen before he died. The Finns were able to take the apron defense on Fuggerstrasse and the Sternschanze and prepared the attack on the actual camp. In the meantime, however, Wallenstein withdrew more and more troops and artillery from its battle formation back into the camp. The Swedish general attack over the largely free field - starting from the Fuggerstraße canal line up to Sonnenstraße - did not begin until late afternoon, the direction of attack corresponded to the course of today's connecting road west up the hill. The left part remained in the artillery fire of the advanced section of the camp fortification (the latter south of the ravine to the border road). The right part west of the connecting road, however, made good progress. The Finns reached the edge of the camp on Sonnenstrasse and conquered several redoubts . The situation became critical for Wallenstein, but dusk prevented the Finns from breaking further into the camp. On the night of September 3rd to 4th, the Swedes stood in the pouring rain in their positions; Gustav Adolf spent the night in a field wagon by the Dambacher Bridge, protected by the Finnish armored riders.

Termination of the battle

Since it was not possible to get heavy artillery over the Rosenberg in the continuous rain and the saltpeter fuses of the muskets hardly ignited due to the humidity, Gustav Adolf broke off the battle in the morning on September 4th and led the troops back to the camp the Hardhöhe without being attacked by Wallenstein. Although the losses were small compared to other battles of the Thirty Years War and the outcome was a draw, Gustav Adolf had suffered a loss of prestige. There were 1200 killed and 200 wounded on the Swedish side, and the number of officers killed was disproportionately high. The Imperial Army mourned around 300 dead and 700 wounded. Since the Swedes had achieved nothing and lost their aura of invincibility, the battle was a point victory for Wallenstein. Both armies were battered, not primarily from the fighting, but from illness (apparently dysentery ) and supply difficulties. Numerous soldiers deserted and thousands of horses perished.

Withdrawal and pillage

Before his departure on September 18, Gustav Adolf had his army deployed to Dambach in front of Wallenstein's camp once again in battle order, but it was a noble gesture and was understood as such by Wallenstein. He also left his camp on September 23rd. In the course of the withdrawal, Wallenstein's troops still practiced arson in many villages around Nuremberg. On September 23, 1632 the pastor of Vach noted : "On this day the enemy set Poppenreuth , Fürth and his camp around the Alte Vesten on fire ...", on September 26 he stated in Fürth "... how beede Brucken doselsbt gantz burned and fell into the water… ”. This meant that there were no more bridges, only the ford that gave Fürth its name . Gustav Adolf came back again on September 28th, "... to inspect the enemy's camp, plus the unfortunate castle on the old hill, where so many brave lads had lost their lives ..." and is said to be at the old fortress later Swedish table called round stone, which was probably destroyed when the first observation tower was blown up in 1945.

On November 16, 1632, the two generals met at the Battle of Lützen , in which Gustav Adolf lost his life. Wallenstein was murdered in Eger on February 25, 1634 . In 1632/33 there was a plague epidemic (15,700 deaths) in Nuremberg, which was overcrowded by refugees, and a general mass death, which killed over 35,000 people. Fürth was cremated in imperial service by Croatians on September 18, 1634 after the Swedish defeat in the Battle of Nördlingen .

Sources / literature

- Georg Tobias Christoph Fronmüller: The history of Altenberg and the old fortress and the battle that took place there between Gustav Adolf and Wallenstein . Fuerth 1860.

- Georg Tobias Christoph Fronmüller: Chronicle of the city of Fürth . Leipzig 1887 (unchanged reprint: Höchstadt ad Aisch 1985. ISBN 3-923006-47-0 )

- Helmut Mahr: Wallenstein's camp. The battle of the old fortress . Nuremberg 1980. ISBN 3-920701-57-7 .

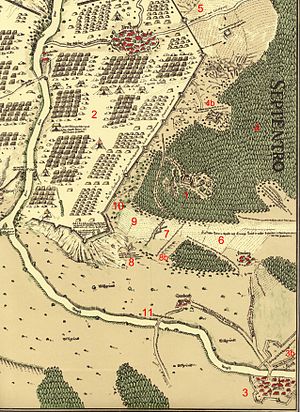

- Helmut Mahr: Wallenstein in front of Nuremberg 1632. His camp near Zirndorf and the battle at the Alte Veste, represented by a plan by the Trexel brothers in 1634 . Neustadt / Aisch 1982. ISBN 978-3-7686-4096-1 .

- Alexander Mayer : The mayors in the flea chamber . Gudensberg / Gleichen 2007. ISBN 978-3-8313-1807-0 . (Edited by Fronmüller 1887 and Mahr 1980/1982 on pp. 39-55).

- Colonel Robert Monro: War experiences of a Scottish mercenary leader in Germany 1626–1633 . (Ed. And translator: Helmut Mahr). Neustadt / Aisch 1995. ISBN 3-87707-481-2 .

- Eduard Rühl: The battle at the "Old Veste" 1632 . Erlangen 1932.

- Hans and Paulus Trexel: Plan of the Wallenstein camp near Zirndorf . Nuremberg 1634. Redrawing and printing: Nuremberg 1932.

Web links

- Zirndorf Municipal Museum, the 1st floor is dedicated to the battle of the Alte Veste

- Circular letter from the Fürth city administrator Alexander Mayer on the 375th anniversary of the battle (PDF file; 217 kB)

- Wallenstein's warehouse near Zirndorf: high-resolution digital copy in the bavarikon culture portal

Individual evidence

- ↑ CV Wedgwood: The 30 Years War . Paul List Verlag Munich 1967. pp. 278–282. ISBN 3-517-09017-4

- ↑ http://www.schwedenlager-bopfingen.de/layout2009/schanzen_1.htm

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento of the original dated December 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.