Swabian Empire

The Swabian Empire (also Swabian Circle ) was one of the ten imperial circles into which the Holy Roman Empire was divided under Emperor Maximilian I in 1500 and 1512 .

Initially, the Swabian Imperial Circle was still in competition with the Swabian Confederation , as the memberships in both organizations partially coincided, but the latter broke up due to the effects of the Reformation and dissolved in the 1530s. After the Peace of Westphalia , two thirds of the district was owned by Catholic imperial estates . In the population, the Catholic proportion predominated with 55.1%, of the 94 imperial estates, in addition to the four "mixed" cities ( Augsburg , Dinkelsbühl , Biberach and Ravensburg ), only 19, i.e. 20.2%, counted asAugsburg confessional relatives . In 1801 the area of the district was 34,314 km². Since 1694, the Swabian Reichskreis was the only Reichskreis to maintain a standing army .

The Swabian Empire actually existed until the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation in 1806, after which it was still legally responsible for the existing financial liabilities. In 1809 it was dissolved retrospectively as of April 30, 1808.

Political position of the circle

General

The political weight of the circle has varied in the three hundred years of its existence and depends on the respective circumstances. Despite their diversity, the members of the Swabian Circle succeeded time and again in finding a consensus and playing an important role as a circle in politics within the empire. The Württemberg director's envoy Johann Georg Kulpis described these conditions in the district in 1696: “… the Swabian Crayß, among all the others, the most extensive, the most dangerous in terms of the situation, and what ratione suae constructionis almost all the difficulties that one would otherwise encounter with the Reich, than when it would be the cause that no right Consilia communia would be led or presented. The proportion of votes, a posteriori, is subject to the fact that not only ratione religionis go into partes, but also ratione membrorum, since spiritual and secular princes, prelates, counts and places compete, hence political whites talk about it, according to their private conveniences different interests and refinements are divided, and nonetheless, because one ratione securitatis exists, as it were, in a common interest, none of this has hindered, nor will by God's grace prevent one from having conducted secundum Leges fundamentale if not communicating Consilia pro sua conservatione and will continue to lead, especially since one was so comfortable with Bißhero that even without this chamfered resolution long ago and from the time one saw oneself destitute before other help, one would have fallen into hostile violence, and therefore into one's complete ruin . "

In the realm, circle associations

The Swabian Empire developed into one of the most active of the ten imperial circles. Above all, its location on the border of the empire in the west and its standing army determined its importance within the empire after 1648.

From 1530 onwards, deputies from individual or all imperial circles met again and again in order to reconcile common interests or to agree on a common approach. In the Reich Execution Order of 1555 it was expressly stated that individual districts should work together under the direction of the Arch Chancellor in the event of a serious breach of the peace .

The War of the Palatinate Succession initially led to an association with the Franconian Empire in 1691, which was extended in 1692 for the duration of the war. In 1697/98 the six southern and western German districts merged in Frankfurt with the Frankfurt Association ("Vordere Kreise": Upper Rhine Empire , Kurrheinischer Reichskreis , Franconian Empire , Austrian Empire , Bavarian Empire and Swabian Empire). The association was renewed during the War of the Spanish Succession and then regulated the occupation of the imperial fortresses of Kehl (see below) and Philippsburg .

In Europe

During the Swedish domination in the Thirty Years War , the evangelical estates of the district participated in the Heilbronner Bund . Georg Friedrich von Hohenlohe was appointed governor-general with military authority and responsibility for public security by the Swedish Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna .

Due to France's policy of annexation under Louis XIV , the Swabian Empire had become its immediate neighbor. Conflicts between France and the emperor or the empire always had direct effects on the district on the one hand and its two large secular territories, Württemberg and Baden, on the other. Both sides were interested in "getting hold of the Swabian region as a preventive measure before the other, or at least neutralizing it". This was especially true when Bavaria and France were allied and Swabia was the link between Alsace and Bavaria. The circle as a whole always saw itself as part of the empire until its end and did not pursue its own European policy . In the case of the two territories mentioned, their ties to the empire still predominated until the 18th century, but there was an increasing tendency to protect themselves through neutrality. After the fall of the empire at the beginning of the 19th century, this led to her joining the Rhine Confederation .

area

expansion

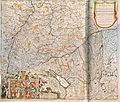

The territory of the Swabian District was not a closed area, as we know it from most modern regional authorities (see map at the beginning of the article). The area was characterized by numerous enclaves and enclaves .

In the west, the district areas extended roughly as far as the Black Forest , some extended beyond that, as far as the Upper Rhine . Many territories in Alsace - although historically closely linked to the "Land of Swabia" - were made into the Upper Rhine District by Maximilian I , as this district was supposed to secure the western border of the empire. The westernmost areas were the Baden territories near Basel . In the east, the district areas extended roughly to the Lech line . The easternmost territories were those of the bishopric of Augsburg and the imperial city of Augsburg , which represented a bulwark against the Bavarian imperial circle . In the south, the district areas extended partly as far as the Upper Rhine and Lake Constance . The areas of Switzerland , which were part of Swabia and Alemannia in the early and high Middle Ages , but now remained independent of a district, began south of it . The southernmost areas of the Swabian district were in Vorarlberg and Liechtenstein , the latter being the southernmost district territory . In the north, the district areas extended beyond the former border of the Swabian duchy , far into the former Franconian area . Roughly speaking, the northern border was formed by a line from Karlsruhe - Heilbronn - Schwäbisch Hall - Dinkelsbühl . The northernmost area of the district was the Württemberg Oberamt Möckmühl .

Large contiguous areas existed in particular in the northwest ( Altwürttemberg in the Neckar basin and on the central Alb , Altbaden on the Upper Rhine around Karlsruhe and Baden-Baden) and in the southeast (territories in the Allgäu ). In between, from the regions in Hegau and on the upper Neckar to the areas on Lake Constance and Danube to the northeast, there were larger enclaves of non-district areas (mostly Austrian areas, areas of the imperial knighthood , areas of the Bavarian and Frankish imperial circles ). The most important exclaves, however, were in Breisgau , Vorarlberg and Liechtenstein. The extensive area of the imperial city of Ulm lay like a connecting hinge between the large closed areas in the north-west and south-east as well as the rather fragmented areas in the Danube region .

Benches

Analogous to the Reichstag, the five imperial estates each formed a bank :

- Secular princes

- Spiritual princes

- Prelates

- Count

- Cities

District

An internal division of the district area into quarters to better carry out police tasks on site took place as early as 1559 based on the former Swabian Federation and was laid down in the 1563 "District Exemption Ordinance". From 1720 onwards, so-called particular district days also met , which were convened by the district directors (Württemberg, Baden, Hochstift Konstanz (Upper Quarter) and Stift Augsburg ).

Maps

Neighboring areas

The close territorial dovetailing of areas of the Swabian District, the Austrian District and areas not belonging to a district (especially imperial knighthood) almost inevitably resulted in regular disputes. Especially in the first quarter of the 18th century, Habsburg tried under Charles VI. to expand its Swabian territories and influence in southwest Germany at the expense of the district.

The knighthoods of the Swabian knightly circle, which were directly within the territory of the district, did not feel they belonged to the circle, but were directly subject to the emperor . The circle's efforts to incorporate them were unsuccessful. This often led to difficulties in the area of internal security, but occasionally it can also lead to cooperation. The Imperial Knights were naturally affected by the activities of the district in the field of coinage and customs duties without being able to influence them. The district communicated its decisions in this regard to the Imperial Knights with the request to observe them.

Territories

Decisive for membership in the Swabian district was the district status of a certain territory (principle of territoriality), not that of a person or that of the owner of a territory (principle of personality).

The very high number of different territories and owners was typical of the Swabian District. The Swabian Circle was "the most patronizing district in polo-lordial Germany". However, the image on the map does not show the most varied of rulership rights associated with individual places and even properties in these territories. Only the Frankish Reichskreis was structured in a similarly diverse way.

In the case of secular rulers, changes in the ownership of some territories arose over time due to the extinction of individual genders, inheritance and the addition of new rankings. This enabled even “foreigners” to become members of the district, such as the Counts of Abensperg and Traun from 1662 by buying the Eglofs rule, around 1700 the Elector of Bavaria as the owner of the Mindelheim and Wiesensteig rule or the Lower Austrian Counts of Sinzendorf as the owner of the rule Tannhausen. As a result of the Reformation, some monasteries (e.g. Herrenalb , Königsbronn , Maulbronn ) were dissolved and thus ceased to be estates.

The Swiss territories ( Hochstift Chur , Fürabbey St. Gallen , Abbeys Beckenried , Disentis , Einsiedeln , Kreuzlingen , Pfäfers , Schaffhausen , Stein am Rhein , St. Johann im Turital , Counts von Brandis as well as the cities of Schaffhausen, Stein am Rhein, St. Gallen ) turned more and more to the Swiss Confederation and did not take part in the tasks of the district. Since they were still retained on the Matrikellisten and the Swabian Circle therefore, their attacks had to continue to raise, he strove for their deletion (district council in 1544 in Ulm ). They were no longer included in later lists.

The economically most important members and banks

The district matriculation relationships of 1795 provide information about the stark differences between the owners of the territories in terms of their economic importance. In the district register it was determined which annual contribution an owner had to pay into the district treasury.

By far the most important contributor was the Principality of Württemberg with 1,407 gulden (1,400 gulden for Württemberg itself, 7 gulden for the Justingen territory ). Four states paid between 200 and 452 guilders: the principality of Baden (452; 302 for Baden-Durlach , 150 for Baden-Baden ), the city of Ulm (370), the bishopric Augsburg (300) and the city of Augsburg (200). This was followed by nine members who each paid in at least 100 guilders: the cities of Hall (180), Gmünd (176) and Rottweil (158), the abbeys of Kempten (130) and Weingarten (118), the Thurn and Taxis family (116), the cities of Heilbronn (104) and Nördlingen (100) and the Abbey of Ochsenhausen (100).

All other members paid less than 100 guilders. The lowest contributions were made in 1795 by the abbeys of Baindt (4), Söflingen (5) and Isny (5).

With regard to the five district banks, the secular princes (2335 guilders, of which Württemberg 1400) and the imperial cities (2247) were by far the two most important groups. The other three banks also paid roughly the same total contribution: Counts and lords (744), prelates ( 740) and clergy princes (625).

With regard to the imperial cities , the massive difference between the high economic performance on the one hand and the low political importance on the other is striking.

Organs of the circle

Despite its composition of many individual territorial rulers, the Swabian Imperial Circle was one of the best organized and the best functioning of all Imperial circles. However, this did not rule out considerable internal differences at times (see below, district advertising office or finance ), since the groups of the district had different interests due to their politically, economically and culturally very different structure despite all cooperation. The religious peace of 1555 also prescribed the same value for both religions. After the Peace of Westphalia until the end of the empire, the denominations - observing each other suspiciously - paid great attention to their rights.

District council

The district council was the decision-making and advisory body for the members of the Reichskreis. It was convened by the princes who wrote the district and met irregularly in an imperial city, in the 18th century only in Ulm. The first recorded district assembly took place in Ulm in 1517, the last in Esslingen in 1804; a total of 140 district councils are occupied.

The sovereigns were seldom personally present at the district assemblies, they "authorized one or more of their mostly legally trained councilors or senior officials, syndici, town clerks and the like as district embassies, who usually led several votes, especially for smaller estates." The district assembly was like the Reichstag a conference of envoys. In contrast to the Reichstag, there was no imperial principal commissioner, but the emperor made use of the right to send commissioners as envoys to the district council. He preferred ambassadors who were themselves members of the circle.

Regardless of his empire class affiliation or actual power, each member had one vote in the district council, so formally the vote of the Duke of Württemberg had the same weight as that of the Abbess von Baindt (with an area of 5.5 square kilometers and 195 inhabitants, the smallest class). Analogous to the Reichstag, the five estates each formed a bank (secular princes, clergy princes, prelates, counts , cities, the latter bank again divided according to denomination ), which initially discussed the issues at hand internally. In contrast to the Reichstag, the district estates voted individually and not according to the five banks. Most of the time, the majority principle (majority principle) applied. In the area of taxation (Latin materia collectarum ), however, the Peace of Westphalia had not made any decision on the validity of majority decisions. In the practice of the circle, however, the tacit agreement emerged that no one was allowed to “vote in the bag” for the other, except in emergencies of the community or “highly necessary” expenses. The expenditures linked to the military constitution were, however, generally regarded as necessary and approved by a majority.

The legally effective resolutions "of the district council were made in circle conclusions (lat. Conclusa circuli ) during and in the district farewell (lat. Recessus circuli ) at the end of the meeting." The resolutions did not require ratification by the emperor as at the Reichstag or by the district estates to be valid . The district secretary dictated them in the district dictatorship, which was formed by the clerks of the district embassies. Since they usually only obligated the district estates, their publication on the district dictatorship was sufficient for legal validity. Overall, the group behaved very restrictively with publications and even expressly prohibited them at times. Resolutions with instructions for the population were, however, printed as “mandates” and distributed and published across the individual stands.

Swabian Circle, meeting of the district council in Ulm , 1669

To relieve the district assembly, a committee, the so-called "Ordinari-Deputation", was set up as early as 1532 to deal with daily business. It consisted of twelve district estates, two representatives from each bank since 1648: the Hochstifte Konstanz and Augsburg as representatives of the clergy, Württemberg and Baden as representatives of the secular princes, the cities of Ulm and Augsburg as well as a prelate and a count each. The deputation was able to provide expert opinions, but not take any decisions. But she prepared this.

A 1563 furnished a Kreiskriegsrat with two representatives of three banks (spiritual princes and prelates as a common bank), which should limit the competence of county colonel, was only until the end of the century. During the Thirty Years' War, the "narrower convention" was set up to prepare for the peace negotiations and continued to exist afterwards. Like the Ordinari deputation, it sat down, checked the district accounts and met around 75 times until 1805. The three Upper German districts (Franconia, Swabia, Bavaria) held eleven joint district assemblies from 1564 to 1683.

District advertising office

The most important office in the district was the district advertising office. “The original, eponymous and most important right of the two princes who wrote the circle was to determine the place and time as well as the subject of discussion for a general or narrow circle meeting and to arrange for it to be convened via the bank chairmen. The two highest-ranking estates, the Duke of Württemberg as secular prince (who at the same time safeguarded the evangelical interests) and the prince-bishop of Constance as spiritual prince (who was considered the head of the Catholic district estates ) had the two jointly according to customary law assigned function of the district advertising princes and together they formed the district advertising office as a district body. The spiritual prince had first rank, the secular the power (mouth and pen) . In the internal relationship between the two princes there were always differences of opinion, which then also had an impact on the circle.

The princes who wrote the district were also commissioned by the Reich Chamber of Commerce and the Reichshofrat to execute their judgments (execution commissions). They in turn instruct their officials (sub-delegates), such as B. the Duke of Württemberg the Oberrat (government councilor from 1710) and the Privy Council . The Duke of Württemberg was in charge, the Bishop of Constance received the files for inspection and countersignature. To enforce such judgments, Württemberg also deployed district military 16 times between 1648 and 1806, but under the supervision of the civil sub-delegates responsible.

Kreisobrist

In the Swabian Reichskreis the office of district bishop was only initially occupied. At the district assembly in June 1622, a district bishop was elected for the last time. The office was given to Duke Johann Friedrich von Württemberg , who held it until his death in 1628.

After the Peace of Westphalia, the Catholic majority in the district feared a Protestant district bishop as well as a Catholic, but Austrian or Bavarian, as a substitute. If, on the other hand, she were to choose a different class than Württemberg for this office, there was a risk that Württemberg would not subordinate his troops to this and separate from the district. Wuerttemberg gradually gave up the endeavor for the district supreme position, especially after it was amply compensated for the loss of the dignity of the district bishop from 1707 through the accumulation of the offices of a district prince, district director and district field marshal. After 1648 the district council itself took over the duties of district bishop.

| Surname | in office |

|---|---|

| Count Wolfgang von Montfort | 1531 to 1537 |

| Count Wilhelm von Eberstein | 1556 to 1562 |

| Duke Christoph of Württemberg | 1563 |

| Duke Christoph of Württemberg | 1564 to 1568 |

| Duke Ludwig of Württemberg | 1569 to 1591 |

| Duke Johann Friedrich of Württemberg | 1622 to 1628 |

District Field Marshal

With the establishment of a standing army (lat. Miles perpetuus ), the Swabian Empire itself became a general. In an effort to be appropriately represented in the councils of war in the high command of the Reich Army , the district created the office of district general (first district general on 8 September 1683 became general sergeant-general on foot Margrave Karl Gustav von Baden-Durlach ), who received the rank of district field marshal from 1696 . He had the power of command over all district troops in war and peace, restricted by district instructions. The first district field marshal was the realm field marshal Margrave Ludwig Wilhelm of Baden-Baden , the Turks Louis, followed on March 22, 1707 by Duke Eberhard Ludwig von Württemberg . In a capitulation ("Capitulation Ihro Hochfürstlicher Highness Eberhardt Ludwigens Duke zu Württemberg p. Because of conferirten Crais-Marshal Office, dd. Esslingen the 25th Martii Anno 1707") his powers were precisely regulated. After him, the office remained with the reigning Duke of Württemberg.

List of district general field marshals :

| Surname | appointment |

|---|---|

| Margrave Ludwig Wilhelm of Baden-Baden (Türkenlouis) | April 9, 1693 |

| Margrave Karl Gustav of Baden-Durlach | 1697 |

| Duke Eberhard Ludwig of Württemberg | March 22, 1707 |

| Duke Friedrich Eugen of Württemberg | September 1795 |

District Directorate

The district directorate, also known as the “district director” in contemporary literature, was not an official, but a factual body of the district. With this office the coincidence of the district bishop with one of the district princes was designated in one person. In the Swabian Empire this was the Duke of Württemberg. For this purpose he built in Stuttgart own circle - firm , in which also the archive of the circle was.

District officials

The district employed various officials to carry out permanent tasks .

- The district secretary kept the minutes of the meetings and was in charge of the district chancellery with the clerks. Their staff consisted of Württemberg servants and they were in Stuttgart. The office went to the meeting place at district meetings.

- The district collector raised the imperial taxes and administered the district treasury. The district treasury (district chest) itself was in the custody of two citizens of Ulm.

- The Münzwardein controlled the coins circulating in a circle .

- The district archivist was responsible for managing the district archive in Stuttgart.

Other military offices are listed in the district militia section .

Functions of the circle

The tasks of the districts were fixed in the Imperial Execution Code of 1555 . In the first few decades, the implementation of the requirements of the emperor and the empire to maintain the imperial peace in the various regions, to help the Turks and to measure political coins. In the Peace of Westphalia, the districts were additionally charged with implementing the peace provisions. Then the focus shifted to securing the imperial borders against Turks and French.

Inner order

The observance of the peace , i.e. the prevention of feuds within the district territory, according to the Imperial Execution Order of 1555 was an important task at the beginning, but hardly played a role in the district.

A good police force was more important to the stands . On the one hand, this included the regulation of almost all areas of daily life. The district issued guild, craftsman and dress codes. On the other hand, this also included taking action against harassment and theft. Above all up to the end of the 17th century, wandering homeless servants (gardening servants) played a role. The district also acted against wandering homeless people (stray gypsies, Jauner and rabble) as well as criminals and gangs of robbers. They were troops Following ( " Streif justifications for cleaning of roads "), captured and in the (existing only in a few cities) work or penitentiaries and on the fortresses housed to work. When these groups grew larger at the beginning of the 18th century, the district decided in 1711 to build their own houses in Esslingen and Donaueschingen. However, since they could not agree on the financing, this was left to the districts . The Augsburg quarter built such a house in Buchloe in 1721 and the Konstanz quarter in Ravensburg in 1725. The Malefizschenk became known , who at the end of the 18th century took the condemned from the smaller estates and the knighthood.

Occupation of the Reich Chamber of Commerce

According to the Reichskammergerichtsordnung of 1555, the Reichskammergericht consisted of the chamber judge and 24 assessors (judges, assessors, Latin nominatio adsessoris cameralis ), six of whom should be by the electors and twelve by the other six imperial districts. be named. The Augsburg Religious Peace of 1555 also stipulated an equal cast with Catholics and Protestants, which was confirmed by the Peace Treaty of Osnabrück. The number of assessors was finally fixed at 50 in the Last Reichs Farewell in 1654. Then the Swabian Reichskreis had to present two Catholic and two Protestant assessors.

The district decision of April 23, 1556 stipulated that the princes writing the district court had to forward the chamber court notification letter to the directors of the four banks, who in turn nominated a suitable candidate for presentation. In addition, Württemberg and Constance could appoint a candidate in their own right; this right expired in 1648. After that, however, the group only occupied two assessor positions.

Coin Order

In individual regions of the empire different coins were mainly in circulation, around 1500 these were indigenous gold guilders , shillings and pennies in southern Germany . The Imperial Coin Order of Esslingen 1524 assigned the probation days , which were to be held twice a year in the six old imperial districts, the control of the coin base and the punishment of coin offenses. The new Imperial Coin Regulations of July 27, 1551 transferred the supervision of coins to the ten imperial circles. It also contained a probation regulation , according to which a probation day was to be held twice a year in a certain city - for the Swabian Empire this was Augsburg. Only the Swabian Reichskreis ordered two mint councils and a mint warrant.

All attempts by the empire to standardize the circulation coins and to prevent the deterioration of money through inferior minting did not lead to lasting success. Above all, the powerful coin stands went their own way until the end of the empire. Attempts by the smaller estates to “create circles against the inferior types of money coinage territories were not effective”. On the probation days in Augsburg, at least sometimes tables with values were drawn up. At times - so z. B. 1714 - the district decided to ban the export of silver coins or redefined the value of coins, but this did not have any lasting success even within the district area.

The district itself minted a Reichstaler with the coat of arms of Württemberg and Constance only in 1694 and a ducat in 1737 . The latter showed a coat of arms of the Swabian District on one side within the inscription "MONETA NOVA IMPERIALIS CIRCULI SUEVICI" with the year 1694, on the other side within the inscription "EBERH LUDO DUX WURT & TECK MARQ RUDOLPH EPIS CONST" the miter or Crown crowned the coats of arms of the two princes who wrote the district.

In addition, individual estates in the district had the right to mint . According to a list published in 1709, there were still lumps that had been coined by Württemberg, the city of Augsburg and the Counts of Montfort and half lumps from Hochstift Augsburg, Fürststift Kempten, Fürstpropstei Ellwangen, Württemberg, Baden and Montfort. Ulm also had a mint in which, among other things, a square silver coin ( kipper ) worth one gulden was minted in 1704 to meet the demands of the French occupation .

Imperial taxes

The key for calculating the tax burden of the individual estates through imperial taxes, but also for district taxes and allocations, were registers , which related to their economic performance in the first quarter of the 16th century. However, since this changed significantly over the course of time (see also section finances ), they no longer corresponded to the actual circumstances after the Thirty Years' War. The adaptation to the financial and economic strength of the estates through reduction (moderation) was therefore a constant and important concern of the district estates in the 18th century.

The only permanent Reich tax was the chamber target (collecta ad sustentationem judicii cameralis destinata) from 1507 to finance the Reich Chamber Court. The tax collection was carried out by the imperial districts, the payment was made in the so-called Legstädten. Augsburg Legstadt was in the Swabian Empire, from there the money went to the Reichspfennigmeister of the Chamber Court to pay the judges and assessors. After that, the Swabian Reichskreis accounted for around 30% of the total contribution. Although all imperial estates had 1 ⁄ 3 of the outstanding debts waived in 1713 , the district pushed for a further discount to 1 ⁄ 10 of the total contribution. By an imperial report of November 8, 1716, 58 Swabian district estates between 1 ⁄ 4 and 2 ⁄ 3 of their attacks were issued. Nevertheless, the district as a whole remained heavily burdened with 22% of a chamber target, especially since since 1719, instead of two annually, seven chamber targets (to finance the newly determined double salaries) have been allocated.

The imperial taxes Roman months or Turkish taxes were only granted for a specific purpose (as the name suggests) by the Reichstag each time and also collected by the imperial circles. The basis was the register of the Worms Reichstag 1521. According to this, the number of estates in the district was 18,668 fl (corresponds to 14% of the Reich). The district therefore constantly endeavored to reduce its share. It was not until the Reichsarmatur of 1681 that the matriculation foot (matricular guilders ) of the Swabian Empire was determined to be 12,006 fl 40 xr. This corresponded to 10.42% of the empire.

The moderation (reduction) of the attacks was a constant effort of the circle.

District militia

From the end of the 17th century, the Swabian Imperial Circle saw itself as a general, especially after the district farewell on May 11, 1694, with which the district council unanimously agreed to maintain a militis perpetui (lat. Miles perpetuus permanent soldier) during all times of war and peace decided. It was also determined that this law could only be repealed unanimously. Formally, this was only a district law, but materially the district estates transferred their military sovereignty from the Peace of Westphalia to the district as a whole.

As commander of the circular distributed those established by the Reichstag team strengths ( Reichsmatrikel ) to individual stands, "put even the troop strength of the county militia firm, incorporated it into weapons genera and bodies of troops transferred management and command of the Circle troops to other places or kept, parts of it before , issued article letters , catering ordinances and instructions, assigned the higher positions of leadership and administration, supervised all military institutions in the district by appointing district commissioners, appointing special inquisition commissions and, from 1709, setting up a general inspection for the duration of a war, and leaving weapons , Procured equipment and other material resources, listened to the bills of the administrators, ruled in the second instance as a higher court of war, even worked as a military entrepreneur and in 1698 rented a regiment to the emperor for the occupation of Freiburg im Breisgau and took rental troops in S old and catering like 1691 to 1698 from Württemberg. He secured a right of recall for his own district troops in the event of an emergency if these command authorities outside of the district were subordinate to them, and he always sought to make an overseas leadership of the district militia dependent on his consent ”.

The orderly of 1717 stipulated for the peace service : “The state may use its contingent for its own security, raids, gate guards etc., but the general district service takes precedence. The companies should contract and exercise at least once every two months, but without complaint from the classes. Every time an entire company moves out, the standards or flags should be picked up. "

The military was also deployed within the district. The “Polizey duties” are described above in the Internal Order section . A second area was the execution of executions both by the district itself (predominantly tax collections) or when executing judgments by imperial courts. The troops required for this were put together on a case-by-case basis and were subordinate to the relevant civil officials. Even the presence of the military by billeting created a certain pressure, as the localities in question often had to provide the soldiers' quarters and food free of charge and also had to raise their payment for this time. Most of the time, the passive presence of the military was enough to achieve the purpose. The military also intervened actively, carried out arrests ordered and / or collected the money in kind. The military was also used against rebellious subjects, for example in 1701 in Hohenzollern-Hechingen and in 1794 during the weavers' unrest in Augsburg.

To support the annual county forces in casu necessitatis extremae the Country Committee of the circle was organized for and on several occasions (1690, 1694, 1696, 1697) mostly in the strength of 6,000 troops mobilized to prepare the defenses and occupy. In May 1691 and August 1693 the district even issued a general “Lands-Aufbott and General-Land-Sturm” in the district, also in 1794.

Imperial fortress Kehl

After the Peace of Rijswijk in 1697, 1,200 soldiers of the district troops were stationed in the Kehl fortress.

During the War of the Spanish Succession , the fortress was besieged with a garrison of 2,265 men (including Kurmainz troops) with 28 cannons under Colonel Baron Enzberg from February 20 to March 9, 1703 by 25,000 French troops under Marshal Villars Mortars from Strasbourg were reinforced. After the capitulation against free withdrawal, Strasbourg / Kehl was developed by France into the strongest fortress in Europe.

Through the Peace of Rastatt and Baden in 1712 which was fortified Kehl as well as the fortress Philippsburg fallen back to the Reich. However, since the empire did not have its own soldiers, the district council took over the fortress in Ulm in autumn 1714 "ad interim" (Latin for meanwhile) and against compensation and granted 1,500 crew members. However, because of the costs involved, the association convention ( Upper Rhine Reichskreis , Kurrheinischer Reichskreis , Franconian Reichskreis , Austrian Reichskreis and Swabischer Reichskreis) in Heilbronn in 1714 did not come to a decision on the maintenance and occupation of the fortresses incurred costs demanded from the assembled circles. Franks (with 1,600 men for Kehl) and Swabia only agreed to provide the crews against reimbursement of their costs until the Reichstag would pass a resolution on the participation of the whole Reich. Habsburg pointed out that it was already burdened by the maintenance of its state fortresses Freiburg im Breisgau and Breisach and demanded support for this, but voluntarily offered three companies on horseback for Kehl and Philippsburg.

On March 6, 1715, the soldiers of the Swabian Empire advanced into the Kehl Fortress, and the Lieutenant General (infantry) Baron Franz von Rodt became the commandant. Initially, the contingents were changed every six months, from 1724 annually. With this change the troops were each mustered . The district only stationed as many soldiers there as could be accommodated in the existing accommodations, only assumed the costs that were incurred for its soldiers and that were necessary for the essential maintenance of the works for the following years and constantly demanded the reimbursement of its costs from the Reich. In 1726 the district allocated 25,000 florins for water construction because of the "threat of war".

On October 12, 1734, French troops crossed the Rhine during the War of the Polish Succession and attacked the fortress on October 19, which was defended with honor by 1,306 district troops and 106 Austrian infantry under the Württemberg Lieutenant General Ludwig Dietrich von Pfuhl , but on October 29 with honor capitulated. The troops (approx. 1,200 men with 2 rounds of ammunition per man and 4 artillery pieces), accompanied by French, withdrew towards Stuttgart on October 30th. After the war the fortress was returned.

In the long period of peace that followed, the district wanted to grind down the fortress in 1751 in order to save costs. This was initially prevented by the margrave's objection, but on October 1, 1754, the fortress was abandoned by an imperial resolution and only a weak Baden garrison remained.

Marching beings

Marshaling was the contemporary term for the passage of foreign but not enemy troops through the district and the logistical problems associated with it. The marching performance at that time was between 25 and 30 kilometers a day, every third day was usually a rest day, so that a passage could take several weeks depending on the direction, during which the troops and their horses had to be fed. Only rarely did the district or the stands affected by the move succeed in receiving cash payment. Above all, Austrian officers only issued receipts, the payment of which by the emperor could only reach the district estates concerned through the involvement of the district (provided that he did not pass the burden on to the district).

The district attempted to organize the marches of foreign troops by establishing routes and appointing district officers as march escorts (march commissioners). He alleviated the burden of the places affected by the passage by ensuring a balance between the districts (directly affected and neighbors), in particular through forage deliveries .

Economic policy

The district did not operate an independent economic policy in the current sense. In times of need he tried to limit the sale of grain outside of the country in order to cover his own needs. The efforts to stabilize the currencies have already been mentioned above. Only the construction of the highway in the late 18th century was also a measure to improve the infrastructure.

Others

Finances of the circle

The estates themselves bore the costs that they incurred directly through the administration and completion of the tasks of the circle (Ordinarium).

The costs of common facilities were raised through allocations (extraordinary). To this end, the district itself developed a right to tax its classes. At the district council of Ulm in 1542, a district levy (district tax, district praesta ) was determined for the first time to cover the running costs and as the location for the district chest Ulm. Since the expenses for the district militia and the conduct of the wars were the largest cost block, the key for the levies was the realm matriculation, taking into account the moderations that the emperor approved of the individual estates. From 1683 the conventional foot was in effect , from which the princes and counts benefited from the other two banks. From 1718 the estates tried to adapt the district register to the changed circumstances in a contentious dispute. In 1721 an Inquisition Deputation (investigative commission) was created, which examined the taxable assets and income of most district estates until the middle of the following year, but the district council could not agree on a new district base. In August 1725, the Inquisition Commission met again and finally completed its work. From September 1726 a moderation deputation advised , which in 1727 submitted an expert opinion for a new circular base. In the final deliberations, they agreed on a "10,000-fl-feet" , which was accepted by the district convention on September 13, 1729 for a ten-year trial, but the decision was suspended again after five days. A renewed attempt in 1731 to introduce the "10,000-fl-feet" failed because of the emperor's objection, who forbade deviating from the moderation set by him. It remained with the conventional base of 1683 until the end of the empire.

Goods subject to district tax but not belonging to a district also had to pay taxes in cash or in kind, but these were mostly not received.

The increasing monetization in the 18th century brought the smaller estates of the district more and more into difficulties, as their income consisted primarily of payments in kind and compulsory labor . The only way to get cash was to sell farm produce or wood. The economic decline of the imperial cities after the Thirty Years War also had a negative impact. Outstanding debts were therefore a constant problem for the district. For this reason, the district recommended the stands z. B. 1709 different methods of how they could get money within their territory:

- Tricesisms of crops and wine

- Excises on grain, flour, meat, beer, wine, merchandise, card games, tobacco

- Cattle tax (in all ways)

- Real estate transfer, inheritance, trade, entertainment tax (for weddings, parish fair)

- Smoke or chimney money

- Poll tax, e.g. B. weekly on a day laborer, servant, maid, unmarried children over 14 years 1 xr up to 2 1 ⁄ 2 xr for a man with 500 fl assets

In addition to the (ordinary) district levies, the district also had (extraordinary) income from contraband revenues and import duties on certain goods (imposto).

Since the funds actually raised were insufficient to pay the district militia, especially in times of war, the district was forced to take out loans from rich district estates or from outside .

The following examples give an impression of the magnitude of finances:

- The profit from Imposto and Kontrebande from 1705 to 1714 was 95,745 fl.

- During the Palatinate and Spanish War of Succession, over 45 million Fl were transferred.

- In 1708 the district took out a loan of 381,000 Fl from the States General , which was only repaid in 1726.

Coat of arms of the circle

The Swabian was the only Reichskreis to have a coat of arms . A single copy showed the three lions of the former Duchy of Swabia (Stauferlöwen) at the top and a cross at the bottom. The origin of the cross cannot be clearly determined as there is no colored original. It could be the cross of the previous Swabian League (red cross on a silver background) or the cross of the Hochstift Konstanz (white cross on a red background). The arrangement in the coat of arms from 1653 shown below and the embossing on the Thaler from 1694, which shows a coat of arms with three lions and a small cross on one side and the coat of arms of Württemberg and Constance on the other, speak against the latter. The flag of the Swabian district contingent from 1796, kept in the Army History Museum in Vienna, shows a cross in an oval above, with the three lions below. This also corresponds to the determination made in Ulm in 1683, “that the standards and flags should be marked with a shield with a cross and three lions as the Swabian Creyses coat of arms”.

However, there were also more splendid versions, such as the second picture below: the coat of arms of the old Duchy of Swabia above, the coat of arms of the Bishopric of Constance on the left and the coat of arms of the Duke of Württemberg on the right.

Cards of the circle

The district also sponsored the making of cards. The Ulm school and arithmetic master David Seltzlin created a first set of maps in various editions from 1572 (see above, 2nd map from the left) to 1591, which were often re-engraved. Up to the beginning of the 18th century, many maps of Swabia and the Reichskreis appeared, also in France and the Netherlands. Jaques Michal created an extensive set of maps. He was a lieutenant in the district troops and a cartographer. His handwritten atlas of 50 sheets Geographical illustration of the whole Hochlöbl. Schwäb. Crayses 1715–1725 is missing, but some of the sheets he printed by Seutter in Augsburg after 1725 are still there. He received a fee of 400fl, the rank of captain and a purchase guarantee for 400 cards from the district for his card . These were bought by the district of Seutter and distributed among the district stands according to the matriculation footprint. In 1729 the district also bought the printing plates.

See also:

Remarks

- ^ Roderich von Stintzing: Kulpis, Johann Georg von . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 17, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1883, pp. 364-367.

- ↑ The Swabian Knight Circle comprised the five cantons of Danube , Hegau-Allgäu-Bodensee , Neckar-Black Forest , Kocher and Kraichgau

- ↑ Criminals could easily move across the border to another territory.

- ↑ Taxes, labor, jurisdiction, grazing and hunting rights, etc.

- ↑ With their backs to the viewer and on the three front benches on the left, the representatives of the imperial cities. On the walls are imperial prelates, ecclesiastical and secular princes. The representative of Ulm, as the host city, also sits on this raised bench (arrow). At the table in the middle probably the Duke of Württemberg as director and district tendering prince.

- ↑ In addition, there were also investigative commissions, Austral commissions to investigate and / or arbitrate legal disputes and manutenence commissions

- ↑ The duke resigned from office that same year, but took it up again in 1564.

- ↑ The Reich, represented by the Reichstag, appointed its own generals

- ↑ since August 27, 1691 Imperial Lieutenant General Field Marshal, since September 30, 1702 (Catholic) Reich General Field Marshal. Because of the parity decided at the Reichstag in Augsburg in 1555, a Catholic and a Protestant field marshal were appointed.

- ↑ Imperial General of the Cavalry, since July 9, 1703 Imperial General of the Cavalry, since September 9, 1712 (ev.) Imperial General Field Marshal

- ↑ Grimm's dictionary: “ from the 15th to the 17th century. The police were understood to mean the government, administration and order, especially a kind of moral supervision in the state and municipality and the related ordinances and rules of procedure, including the state itself, as well as state art, politics. "

- ↑ Example for Upper Swabia: Schwarzer Veri

- ↑ Food order donation from 1717, XIV

- ↑ RKGO 1555, Tit. 1 § 3: "under which all half of the part who have been properly trained and the other half outside of the knighthood, who are qualified and skilled, as follows, are to be appointed and ordered."

- ↑ lat. "New coin of the Swabian district"

- ↑ Ulm money

- ^ The Wuerttemberg councilor Johann Georg von Kulpis demanded and achieved unanimity on the grounds that the matter ran into tax law and aimed at a permanent institution.

- ↑ Land Committee or State Committee at that time meant the raising of troops from drafted residents.

- ^ The Franconian District also took over the fortress Philippsburg.

- ↑ The commandant of Philippsburg, General Feldzeugmeister Eberhard Friedrich von Neipperg, had worked out a cost estimate of 205,793 Fl for this fortress alone

- ^ For example, when French troops passed through in 1741 in the War of the Austrian Succession

- ↑ When two “Walloon” regiments in Austrian service moved through from Alsace, accompanied by commissioners of the district, the district incurred costs of 369,039fl 12x

- ↑ moderation in its old meaning moderation ; here specifically a reduction in taxes

- ↑ funda alienta = goods obtained in the district area through purchase or inheritance to non-district members

- ↑ The flag was delivered at the disarmament in 1796.

- ^ Coats of arms on the title pages: 1563 printed district expulsion order and 1737 war ordinances and regulations of the Swabian district, Stuttgart 1737.

- ↑ On the title page “Deß Heil. Romis. Reichs / And belonging to the estates of the praiseworthy Swabian Kraiss unanimous constitution; Which masses / mediated divine grace and assistance / to maintain religious and land peace / also to avert foreign violence. Made in Ulm / Anno 1563. Anjetzo but / due to the loss of copies / published again. Sampt two useful registers. ULM / in relocation Balthasar Kühnen G Wittib / book dealer "

- ↑ For Michal's map series, see Ruthardt Oeme, The History of Cartography of the German Southwest. P. 48ff.

See also

literature

- The Holy Roman Empire and its members of the lavish Swabian Kraiss Ainhellige and the final comparison of the constitution , 1563 (constitution, (digital copy ) )

- Heinz-Günther Borck: The Swabian Empire in the Age of the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1806). W. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart 1970. ( Review by Eberhard Weis )

- Winfried Dotzauer: The German Imperial Circles (1383-1806). History and file edition . Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-515-07146-6 ( google.de ).

- Hans Hubert Hoffmann (Ed.): Sources on the constitutional organism of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation 1495–1815 . Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft Darmstadt, Darmstadt 1976. - The same, edited for study use by Heinz Duchhardt. Darmstadt 1983, ISBN 3-534-09080-2 .

- Martin Fimpel: Imperial Justice and Territorial State, Württemberg as Commissioner of the Emperor and Empire in the Swabian District (1648–1806). bibliotheca academica Verlag, Tübingen 1999, ISBN 3-928471-21-X .

- Fritz Kallenberg: Late Period and End of the Swabian Circle. In: Yearbook for the history of the Upper German cities. No. 14, Esslingen / N. 1968, ISSN 0341-9924 , pp. 61-95.

- Adolf Laufs: The Swabian Circle. Studies on unification and the imperial constitution in the German south-west at the beginning of modern times . Scientia Verlag, Aalen 1971, ISBN 3-511-02836-1 .

- Reinhard Graf von Neipperg: Emperor and Swabian Circle (1714–1733). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-17-011187-6 .

- Andreas Neuburger: Confessional conflict and end of war in the Swabian Reichskreis. Württemberg and the Catholic imperial estates in the south-west from the Peace of Prague to the Peace of Westphalia (1635–1651). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-17-021528-3 .

- Gerd Friedrich Nüske: Imperial circles and Swabian district estates around 1800 . Epithet to Map VI, 9 of the Historical Atlas of Baden-Württemberg. Stuttgart 1978. online as PDF

- Peter-Christoph Storm : The Swabian Circle as a general. Studies on the military constitution of the Swabian Reichskreis from 1648 to 1732. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1974, ISBN 3-428-03033-8 .

- James Allen Vann: The Swabian Circle. Institutional growth in the Holy Roman Empire 1648-1715. Libraire Encyclopédique, Brussels 1975.

- Wolfgang Wüst (ed.): The "good" Policey in the Swabian Reichskreis, with special consideration of Bavarian Swabia. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-05-003415-7 . Collection of sources with introduction ( table of contents , PDF, 472 kB).

- Wolfgang Wüst (Ed.): Imperial circle and territory: rule over rule? Supraterritorial tendencies in politics, culture, economy and society. A comparison of southern German imperial circles . Jan Thorbecke Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-7995-7508-1 . ( Table of contents , PDF, 79 kB). Conference proceedings, Irsee from March 5th to 7th, 1998.

- Wolfgang Wüst, State peace policy across borders: Measures against beggars, crooks and vagabonds , in: Ders. (Ed.), Reichskreis and Territorium: the rule over the rule? Supraterritorial tendencies in politics, culture, economy and society. A comparison of southern German imperial circles (Augsburg contributions to the regional history of Bavarian Swabia 7) Stuttgart 2000, pp. 153–178. ISBN 3-7995-7508-1 .

- Main State Archives Stuttgart holdings L 9 and C 9 to 15 SchwäbischerKreis

- Generallandesarchiv Karlsruhe inventory 83 Reichskreis

Web links

- Overview of the imperial estates viewed on December 23, 2008

- Max Plassmann: Between the Imperial Province and the League of Estates. The Swabian Empire as the framework for action by inferior estates , lecture at the Working Group for Historical Regional Studies on the Upper Rhine eV on November 10, 2000

Individual evidence

- Osnabrück Peace Treaty

- ↑ Osnabrück Peace Treaty (Instrumentum Pacis Osnabrugensis, IPO) Art. V § 3: “The cities of Augsburg, Dinkelsbühl, Biberach and Ravensburg retain their property, rights and religious practice after this deadline [1. January 1624]. With regard to the appointment of the council and other public offices, there should be equality and numerical parity among the relatives of both religions. "

- ↑ According to IPO Art. XVI §§ 9ff, the district had to raise the stationing and abdication funds for 14 Swedish regiments

- ↑ IPO Art. V § 53

- ↑ IPO Art. VIII § 2: Latin ius foederis = right to conclude alliances, derived from it Latin ius belli ac armorum = the right to wage war and the right to arm

- Hans Hubert Hoffmann: Sources on the constitutional organism of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation 1495–1815. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1976.

- ↑ in the order and order of the Reichsregiment at the Reichstag in Augsburg: “§ 8. The third Kreyß understands the Bißthumb, principality, land and area of the bishops of Chur, Costentz, Augspurg, the Herz von Wirtemberg, the Marggrafen von Baden, die Society of St. Georgen Schild, the knighthood in Hegaw, also all and every prelate, count, lord, Reichstätt in the land of Swabia. ”Quoted from Hofmann, p. 23.

- ↑ "§ 7. (The Swabian Kreyß) Item of the Bishop of Chur, Costentz and Augspurg, Duchy of Wirtenberg, the Margraves of Baaden, the St. Georgen Schild Society of the knighthood in Hegau, also all and every prelate, count, lord and empire - Cities in the state of Swabia should also have a Kreyß. ”Quoted from Hofmann, p. 68.

- ↑ “Youngest Reichs Farewell” 1654, § 183: “In Creyß's actions, the Maiora should take place at any time about the constitutional matters contained in the execution order and the lesser voice should be bound to give in to several.” Quoted from Hofmann, P. 216.

- Winfried Dotzauer: The German Imperial Circles (1383-1806). Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart, 1998, ISBN 3-515-07146-6 , GoogleBooks

- ↑ Dotzauer, p. 177.

- ↑ Dotzauer, p. 141.

- ↑ according to Dotzauer, page 585ff: The joint meetings of several or all circles from 1530 to 1796.

- ↑ Dotzauer, p. 145.

- ↑ Dotzauer, p. 144.

- ↑ Dotzauer, p. 146.

- ↑ Dotzauer, p. 145.

- ↑ Dotzauer, pp. 587f.

- ↑ Dotzauer, p. 474.

- ↑ quoted from Dotzauer, p. 453.

- Georg Siegemund: Securitas inter cives et contra exteros defensio - the imperial circles in the constitution of the old empire using the example of the Swabian district

- Reinhard Graf von Neipperg: Emperor and Swabian Circle (1714–1733). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-17-011187-6 .

- ^ Graf von Neipperg, p. 53.

- ↑ So z. B. 1714 Count Froben Ferdinand von Fürstenberg-Meßkirch , who was also director of the count bank. Graf von Neipperg, p. 8.

- ^ Graf von Neipperg, p. 61.

- ^ Graf von Neipperg, p. 24.

- Martin Fimpel: Imperial Justice and Territorial State, Württemberg as Commissioner of the Emperor and Empire in the Swabian District (1648–1806). bibliotheca academica Verlag, Tübingen 1999, ISBN 3-928471-21-X .

- ↑ Fimpel, p. 593ff.

- ↑ Fimpel, p. 36.

- ↑ Example: In December 1784 a command of 50 soldiers marched - composed of the district contingents of Memmingen (1 captain, 1 sergeant, 1 corporal, 20 common, 1 drum), Mindelheim (1 sergeant, 12 common) and Kirchheim (1 corporal, 12 common) with a daily salary of 5 guilders for the captain, 30 cruisers for the sergeant, 34 cruisers for the corporal and 18 cruisers for the common - in the rule of Kirchheim . Quoted from Fimpel, p. 273.

- ↑ Fimpel, p. 29f.

- Leo Ignaz von Stadlinger, History of the Württemberg Warfare. K. Hofdruckerei zu Guttenberg, Stuttgart 1856.

- ↑ Stadlinger, p. 94.

- ↑ Stadlinger, p. 94: 1 captain, 1 adjutant, 1 captain des portes , 1 gunsmith, 1 henchman, 1 profoss were commanded there by the artillery ; from the medical service 1 garrison medic, 1 surgeon; also 1 garrison preacher and 1 barracks manager from the administration, who was appointed steward in 1720.

- Peter-Christoph Storm: The Swabian Circle as a general. (= Writings on constitutional history. Volume 21). Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1974, ISBN 3-428-03033-8 .

- ↑ Storm, pp. 55 ff and 149.

- ↑ Storm

- ↑ quoted from Storm, p. 48.

- ^ Storm, p. 54.

- ^ Storm, p. 136.

- ↑ Storm, p. 138.

- ^ Storm, p. 160.

- ↑ Storm, p. 156 ff.

- ^ Storm, p. 215.

- ↑ Storm, p. 14f.

- ↑ quoted from Storm, p

- Karl Hermann Freiherr von Brand: Little Uniform Knowledge of Baden-Württemberg. G. Braun publishing house, Karlsruhe 1957.

- ↑ quoted from Freiherr von Brand, p. 78.

- Others

- ↑ after Georg Siegemund

- ↑ MS Pingitzer: Derer dreyen in the Münz-Weesen corresponding upper Reichs-Creyßen, Franconia, Bavaria, and Swabia drafted coin patent, as decided at the Münz-Probations-Convent in Augspurg , Augsburg 1761.

- ↑ Georg Heinrich Paritius, Cambio Mercatorio : Renewed Specification of the coarse varieties and how those with the An. 1709. d. The Müntz Probation Convent held in Nuremberg on February 22nd, according to the Ducatens at 4th florins and the Reichs-Thalers at 2nd florins to be accepted in trade and change with the exclusion of others, was resolved.

- ↑ CORPVS JURIS MILITARIS Des Heil. Rom. Reichs, Wherein the law of war as well as Der Roem. Kayserl. Majesty as well as the same realm and its circles, in general, the same of all Churfuersten and whose most powerful Fuersten and Staende in Germany is included ... ( Memento of the original from August 14, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Leipzig 1732, pp. 457ff.

- ^ Johann Jacob Moser: Teutsches Staatsrecht. Part 26, 1746 (quoted from Karl v. Seeger): "I do not know that any one of the Craysen qua talis had a coat of arms, except the Swabian one in which the flags of the Crays militia were and on which the coins struck by the whole Crayses, wears a divided shid, in the upper quarters of which three leopards tend to appear, but in the lower one a cross; which is used to be the coat of arms of the long-departed dukes of Swabia. "