Dinkelsbühl

| coat of arms | Germany map | |

|---|---|---|

|

Coordinates: 49 ° 4 ′ N , 10 ° 19 ′ E |

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Bavaria | |

| Administrative region : | Middle Franconia | |

| County : | Ansbach | |

| Height : | 442 m above sea level NHN | |

| Area : | 75.17 km 2 | |

| Residents: | 11,836 (Dec. 31, 2019) | |

| Population density : | 157 inhabitants per km 2 | |

| Postal code : | 91550 | |

| Area code : | 09851 | |

| License plate : | AN , DKB, FEU, ROT | |

| Community key : | 09 5 71 136 | |

| City structure: | 67 parts of the community | |

City administration address : |

Segringer Strasse 30 91550 Dinkelsbühl |

|

| Website : | ||

| Lord Mayor : | Christoph Hammer (CSU) | |

| Location of the city of Dinkelsbühl in the Ansbach district | ||

Dinkelsbühl is a large district town in the Ansbach district in Middle Franconia . The former imperial city is an important tourist destination on the Romantic Road due to the exceptionally well-preserved late medieval cityscape . Dinkelsbühl has been a major district town since 1998 and a member of the Bavarian Association of Cities since 2013 .

geography

Geographical location

Dinkelsbühl is close to the border with Baden-Württemberg. The city is located on the Wörnitz in the southeast of the Frankenhöhe , which belongs to the Keuper level in the south-west German layer level country between the Main and Danube . The Wörnitz formed a flat, triangular valley basin, which is almost completely filled by the old town of Dinkelsbühl, pushed to the west by a sandstone knoll east of today's course. In the north-west and south-east the city wall runs along the morphological edge of the bubble sandstone, which forms a plateau on the other side of the city moat between the valley cuts of two streams that flow into the Wörnitz from the west. In the northern valley cut, in which the bubble sandstone was washed away down to the Lehrberg layers below, the Sauwasenbach flows, which through its alluvial sand created a ford that is still visible today at low tide and which was probably an incentive to found a place at this location. In the east, the old town is bounded by the Mühlgraben, a straightened arm of the Wörnitz, beyond which the Wörnitzvorstadt is still part of the Dinkelsbühl old town area.

geology

The agriculturally most productive soils are in the valley floors of the Wörnitz; Even the less productive soils on the bubble sandstone in the west are still mainly used for agriculture. The castle sandstone heights in the east of the city have hardly been cleared and are largely covered by the Dinkelsbühler Stadtwald Mutschach . Since the water-retaining clay layers of the upper Keuper are in place in many places , pond management is of typical regional importance. Even today, the old town looks very protected and secure in the floodplain of the Wörnitz, which in the form of the motto romanticism of water and meadows got a symbolic character for the city.

Neighboring communities

|

|

City structure

There are 67 officially named parts of the municipality (the type of settlement is given in brackets ):

|

|

|

|

The Romantic Road

The topography offered good conditions for defense. This fact, as well as the crossing of two important trade routes Baltic-Central Germany-Italy and Worms-Prague-Cracow from suburban times, which met at the Wörnitzfurt, were decisive reasons for the Staufer fortification of Dinkelsbühl around 1130.

There are indications of early medieval connections from Dinkelsbühl to the northwest in the direction of Crailsheim , to the southwest in the direction of Ellwangen , to the east in the direction of Nuremberg , to the north in the direction of Rothenburg ob der Tauber and to the south in the direction of Ulm . The importance of these supposed "elevated roads" is usually overestimated, but one of them is again important for Dinkelsbühl today: the old north-south road through Dinkelsbühl (1236, "Dinkepole"), a trade route along the valleys of Tauber , Wörnitz and Lech , on the middle ages also pilgrims from northern Germany to Rome attracted. The mayor of Augsburg, Wegele, christened this section of Bundesstraße 25 in 1950 for reasons of tourism promotion, the Romantic Road . It connects a number of cities with well-preserved medieval city centers, in the central area between Würzburg and Augsburg in particular Rothenburg ob der Tauber, Dinkelsbühl, Nördlingen im Ries and Donauwörth . Dinkelsbühl has been the headquarters of the “Romantic Road” working group since 1985.

The old town

Dinkelsbühl's first urban development, which is now known as the core city or inner old town, took place around 1130. It was developed as a base and link between the Hohenstaufen household goods when the Hohenstaufen and Welfs fought for the German crown. It is assumed that a predecessor settlement around a Carolingian royal court, founded around 730, was located on the Wörnitzfurt.

The surrounding Keuperwald area was, so one deduces from the place name endings, settled in the later Franconian conquest in the 8th century. The egg-shaped city wall at that time because of the cheaper defense can still be seen in the cityscape today. The streets of Spitalgasse, Untere Schmiedgasse, Föhrenberggasse and Wethgasse that border them run in front of the Hohenstaufen city moat, which was in front of the wall . The city wall itself ran within the first blocks, u. a. between Unterer Schmiedgasse and Elsasser Gasse as well as between Föhrenberggasse and Lange Gasse, as can be seen from the property boundaries, the width of the courtyards and the building structure (the Staufer city wall is part of some house walls) and the archaeological findings.

In contrast to most of the city complexes of the 13th century, for example in Rothenburg, there is no central, rectangular market square in the grown, not planned Dinkelsbühl, but market streets with sometimes funnel-shaped extensions like the Weinmarkt, which widens to 36 m. The streets were later reserved for trading in different products in individual sections. In addition to the Weinmarkt, today's Segringer Straße was divided into a Brettermarkt, Hafenmarkt, Bread Market and Schmalzmarkt in the area of the inner old town; behind the New Town Hall was the pig market. Today's Altrathausplatz was the cattle market and the entire inner Nördlinger Strasse was the leather market. The Staufer city turned out to be functional. It was already so efficient when the city was expanded in the 14th century that the city center and the economic center did not have to be shifted. With the construction of St. George's Church , completed in 1499 , the dominant symbol of the city's cultural prosperity emerged. The structural appearance of the old town has not changed fundamentally since then.

In the economic heyday of the city of Dinkelsbühl, the 14th and 15th centuries, suburbs were laid out beyond the Hohenstaufen city gates, probably in the order Rothenburger, Segringer, Wörnitzvorstadt and Nördlinger Vorstadt. From 1372 the old town of Dinkelsbühl received its present form with the construction of the city wall ; The Wörnitzvorstadt was secured with palisades, as the surrounding water offered it natural protection. The Rothenburg and Nördlinger suburbs were opened up to the main axis with a parallel alley, in the north through the Bauhofgasse and in the south through the Lange Gasse. The buildings in Wörnitzvorstadt are narrow and almost without open spaces. The flammable trade (blacksmiths) was located in the Rothenburg suburb. East of the Schmiedgassen of the Rothenburg Quarter is the Spitalhof as a separate complex. The rural Nördlinger suburb was also populated by dyers and tanners because of the water in the Stadtmühlgraben. On the loosely built slopes of the Rothenburg, Segringer and Nördlinger suburbs, u. a. the cloth makers and weavers who relied on open space for their drying frames. The Capuchin monastery and the Teutonic Order Court were also located here ; the remaining open spaces were taken up by orchards and horse pastures. The Carmelite monastery , on the other hand, was located on the oldest church square at the centrally located Carolingian royal court on the Ledermarkt. In contrast to most historic cities, all of the city extensions in Dinkelsbühl in the 19th and 20th centuries took place outside the old town. This is surrounded by a complete walling, to which the inner city moat, excavated in the sandstone, connects to the west and south. In the north are the Hippenweiher and Rothenburger Weiher with the outer city moat and in the east the city mill moat with the flood plains of the Wörnitz. The silhouette of the city seen from the Wörnitz side is probably the most striking view of the city and has been imitated since Matthäus Merian's engraving of 1643.

The division of the old town into an inner old town and an extension area can be recognized in particular by the width of the house fronts of the so-called courtyards. This measures around 15 m on the market square, 12.5 m in the wider area of the city center and 10 m or less in the suburbs.

The St. Georg Minster visually dominates the whole city and can be described as a dominance of the first order. The second-order dominants are the four late medieval gate towers that tower above the old town and all other public buildings. With the exception of the Nördlinger Tor, they are only passable in one lane, which brings the preservation of the old town ambience into conflict with motorized individual traffic. The structure of the inner old town, in particular the main street parallel and at right angles to Wörnitz and the parallel side streets, was retained. The same applies to the distances between the access units, which are exactly the same length as the distance between the old city gates and the center (approx. 150 m).

An exception to this is the Nördlinger Vorstadt, where the new one is 300 m away from the old city gate. Nördlinger Straße also stands out structurally from the other old town streets, as it changes direction and the house fronts do not run parallel to the street, but rather the houses are staggered and always offset from one another, which makes the street something special and memorable.

climate

In Dinkelsbühl the average amount of precipitation in the year is 769 mm (Karlsholz) and 746 mm (Oberwinstetten).

history

Origin of the settlement

In the 10th century, the intersection of the important trade routes Baltic-Central Germany-Italy and Worms-Prague-Krakow near the ford was fortified with a tower hill . The street coming from Worms is occasionally, but incorrectly, referred to as Nibelungenstraße . The city was first mentioned in a document as "burgum tinkelspuhel" in 1188 in a marriage certificate from Emperor Barbarossa for his son Konrad von Rothenburg . Even then, the place was an important trading center and Staufer base due to its favorable traffic situation. The place name is derived from the field name of the same name, whose basic word "bühel" ( mhd. For hill) and whose defining word is the personal name "Dingolt" or "Dingolf" and therefore means Zum Hügel des Dingolt .

Imperial city

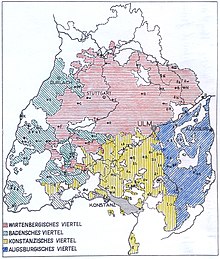

In the Holy Roman Empire , Dinkelsbühl was able to achieve the status of imperial immediacy during the 13th to 14th centuries , which resulted in the imperial city of Dinkelsbühl . From then on, the city received royal and imperial privileges. It developed into a small city republic with attached territory. In the Reichstag , the city sat on the Swabian city bench . When the empire was divided into imperial circles at the beginning of the 16th century, Dinkelsbühl became part of the Swabian district and thus one of its north-eastern outposts. The city was also represented on the city bank in the Swabian District and was ranked 13th out of 31 imperial cities .

Mediatization until today

In 1802 Dinkelsbühl lost its independence from the imperial city and became part of the Electorate of Bavaria . By swap, Dinkelsbühl was incorporated into the Prussian administrative area of Ansbach-Bayreuth in 1804 , the two previous territories of which had belonged to the Franconian district . Together with Ansbach-Bayreuth, Dinkelsbühl was annexed by Bavaria in 1806, which rose to become the Kingdom of Bavaria through collaboration with the French Emperor Napoleon . When Bavaria was divided into Swabian, Franconian and Bavarian administrative districts, reference was made to the earlier imperial districts. Due to the Ansbach interlude 1804-1806, Dinkelsbühl finally came to Middle Franconia , although it had belonged politically to Swabia for centuries.

With the community edict (early 19th century), the tax district Dinkelsbühl was formed. The following places belonged to this: Carmeliterhaus, Felden, Gaismühle , Hammermühle , Hirtenhaus, Hungerhof , Kobeltsmühle , Lohmühle , Mögelins-Schlößlein , Mutschach , Mutschachermühle, Neumühle , Obere Ölmühle, Radwang (partly), Reichertsmühle , Siebentisch, Strickerwalkmühle , nonsensical ones Mill , Weiherhaus and Weißhaus .

Dinkelsbühl was until the dissolution of the district Dinkelsbühl in 1972 its district town.

Witch hunt

From the witch hunts in Dinkelsbühl, five witch trials with executions are known between 1613 and 1661 . In 1611 three women were accused of witchcraft , two death sentences are attested for 1613, the execution of a Protestant midwife for 1645 and a larger series of trials with eight women accused in 1655 and 1656. One woman was burned alive, seven women were beheaded and then burned, one woman was beheaded and not burned, one man was beheaded and burned. In fact, between 1649 and 1709 another 40 cases of witch accusations were heard in the council court that did not result in execution. Accused persons were punished with exile, prison, the fool's house or the neck violin and had to apologize. The files are incomplete, but the minutes of the inner and secret councils have been handed down and were transferred by the city archivist.

In 2006 a permanent exhibition on the history of witch hunts was opened in Dinkelsbühl in the Rothenburg Gate. The " Embarrassing Questioning" took place in the "Drudengewölbe" above the gateway . There, the names of the victims are engraved on glass stones set into the floor of the torture room. Since May 2012 the exhibition has been in the "House of History Dinkelsbühl" in the "Old Town Hall". The following fatalities are listed on an exhibition board:

| process | year | Victim | description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1613 | Maria Gurr, Catharina Gassner |

The two Catholic sisters from Ellwangen, who married in Dinkelsbühl, were accused of witchcraft in an Ellwangen witch trial . A sister who was pregnant confessed to all allegations in the amicable questioning. She was cremated alive after giving birth. The other sister confessed to being tortured by " raising " and was beheaded with a sword and then burned. |

| 2 | 1645 | Euphrosine | The Protestant midwife was arrested in 1645 as an alleged witch. She was forced to become Catholic. She was condemned by a Catholic Inner Council and on July 7, 1645 was executed with the sword and then burned. |

| 3 | 1655/1656 | Sibilla Bidermann, Catharina Deubler, Margaretha Link, Eva Peter, Anna Strauss, Margaretha Buckel |

One woman was charged with attempted poisoning by her husband and arrested. Under the torture, she accused her mother, sister, and other women of witchcraft. Five of the women arrested were executed with the sword and Margaretha Buckel died while in custody. Susanna Stadtmüller and Walburga Mangoldt were banned from the city, with the relatives having to pay the legal costs and a fine. The verdict was passed by the Evangelical Catholic Inner Council, which was made up of equal numbers. |

| 4th | 1658 | Sebastian Zierer | The man was charged by a neighbor and his son-in-law with causing leg paralysis and pain. Under the torture, he confessed to poisoning many people with powder. He was sentenced to death by beheading and burning for witchcraft. |

| 5 | 1660/1661 | Barbara Huckler | The woman was accused of causing her daughter-in-law's suicide. Although the accused's husband filed a complaint against the defamation with the Inner Council, she was arrested and interrogated for witchcraft. Under the torture, she admitted to poisoning people with "druden powder". She was also beheaded and burned. |

Religions

The Reformation , which was introduced early, led to an imperial city Protestant state church, which was ended by the subsequent Counter-Reformation . The denominationally hostile, strongly majority Protestant citizenship was ruled by a Catholic magistrate from 1552 until the peace agreement of the Thirty Years War . It was not until 1649 that the confessionally mixed city became an equal imperial city with equal religions: from now on, mayors, councilors and all offices were denominationally filled with the same number or alternately. The new council constitution, however, resulted in an ongoing dispute between the council parts and among the citizens.

Dinkelsbühl is now part of the Catholic diocese of Augsburg , Deanery Nördlingen , and on the Protestant side it is a separate deanship seat of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria .

As free churches, there is a Free Evangelical Community and the Liebenzeller Community . Even Jehovah's Witnesses and the New Apostolic Church are represented in Dinkelsbühl by municipalities. At the 1987 census , the population of the city was about 63% Protestant and about 33% Catholic. A little over 3% of the population either belong to other religious communities or to no religious communities. According to the 2011 census , 57.8% of the population were Protestant, 29.5% Catholic, 1.2% Orthodox and 10.9% belonged to another or no religious community.

Since the 13th century, Jews settled in smaller settlements in Dinkelsbühl several times as royal chamberlains and protective relatives of the imperial city, each of which was ended by expulsion or persecution. During the Thirty Years' War the city took in six Jewish families in 1636, the last Jew moved away due to excessive indebtedness in 1712. After that, Jews lived in the city again from 1786, naturalization could only take place from 1861 after the Jewish register was abolished. The youngest Jewish community was established here before 1882 with a room synagogue in Klostergasse 5 until the November pogroms in 1938 . On November 9th and 10th, rolling commandos raided the apartments and devastated the synagogue. On November 10th and 11th, all 19 women, children and men left their city home “under the pressure of the circumstances”, one man in absentia. Between 1786 and 1938 Jews lived in around a fifth of the old town houses. Ten citizens of Israelite faith born in Dinkelsbühl were victims of the Shoah . The stumbling blocks in front of the residential buildings, which were laid in 2009, are a reminder of this, as is a memorial plaque on Klostergasse 5, where, in addition to the synagogue, there was also a mikveh. In December 2013, US President Barack Obama commemorated the Jews of Dinkelsbühl at the White House Hanukka Reception . The occasion was the use of a special Hanukkah chandelier made by Manfred Ansbacher, who was born in Dinkelsbühl in 1922: Ansbacher, who was called Anson in the USA, had made a chandelier with candles on statues of liberty. At the White House Hanukka Reception , the US President said that Anson experienced "the horror of Kristallnacht" as a teenager and had lost a brother (Heinz) in the Holocaust. Anson was looking for “a place where he could live his life and practice his religion free from fear. For Manfred and for millions of others, America became such a place. ”During a public tour on November 9, 2014, the stumbling blocks were brought back to the general awareness.

Incorporations

| Former parish |

Residents (1970) |

date | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esbach | 96 | April 1, 1971 | |

| Hellenbach | 152 | July 1, 1971 | |

| Knittelsbach | 313 | April 1, 1971 | Incorporation of 248 of the 313 residents, reclassification of the other residents to Wilburgstetten |

| Langensteinbach | 167 | 1st January 1971 | |

| Oberradach | 107 | April 1, 1971 | |

| Segringen | 284 | April 1, 1971 | |

| Seidelsdorf | 298 | July 1, 1970 | |

| Sinbronn | 519 | May 1, 1978 | |

| Waldeck | 126 | April 1, 1971 | |

| Forest house | 147 | 1st January 1971 | Incorporation of 78 of the 147 residents, reclassification of the other residents to Schopfloch |

| Weidelbach | 279 | May 1, 1978 | |

| Wolfertsbronn | 323 | 1st January 1971 |

Population development

Of the 11,720 residents of Dinkelsbühl, 2,203 lived in the old town in 1999. In terms of social structure , the old town has had to struggle with the two intertwining problems of aging and emigration over the past few decades. In 1966, 3,766 people lived in the old town area, ten years later the figure was only 2,753, a drastic decrease, which was mainly a result of young people moving to new development areas. In the 1970s, for example, the proportion of over 65-year-olds in the old town area was 22%, but only 13% in the other districts. The obsolescence results from the selective emigration of young families, who can no longer meet their increased demands for space and open space in the old town and are also more mobile than older people. The city counteracted the problem in particular by making the green spaces in front of the old town more accessible by building new old town entrances. However, there is no public children's playground in the old town itself - the playground at Muckenbrünnlein belongs to a church institution and is not open to the public. The public playground closest to the old town can be reached relatively quickly through the bleach gate, but was not enough for the entire old town population. In recent years, therefore, additions have been made with a slide on the grounds of the Christoph von Schmid elementary school and in the city park northwest of the walls.

In the period from 1988 to 2018, the population increased from 10,668 to 11,825 by 1,157 inhabitants or 10.9%.

| year | Population without incorporations |

Proof of E.oeO |

Population with incorporations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 4,496 | ||

| 1900 | 4,573 | ||

| 1910 | 4,800 | ||

| 1925 | 5,067 | ||

| 1933 | 5,155 | ||

| 1939 | 4,809 | 7,268 | |

| 1940 | 4,798 | ||

| 1950 | 10,714 | ||

| 1961 | 7,874 | 10,546 | |

| 1970 | 8,034 | 10,711 | |

| 1979 | 10,761 | ||

| 1991 | 11,271 | ||

| 1995 | 11,515 | ||

| 1999 | 11,543 | ||

| 2000 | 11,549 | ||

| 2001 | 11.606 | ||

| 2002 | 11.605 | ||

| 2003 | 11,665 | ||

| 2004 | 11,672 | ||

| 2005 | 11,616 | ||

| 2006 | 11,584 | ||

| 2007 | 11,515 | ||

| 2008 | 11,455 | ||

| 2009 | 11,443 | ||

| 2010 | 11,482 | ||

| 2011 | 11,546 | ||

| 2012 | 11,287 | ||

| 2013 | 11,315 | ||

| 2014 | 11,389 | ||

| 2015 | 11,538 | ||

| 2017 | 11,786 |

politics

mayor

Incumbent Christoph Hammer was re-elected with 73.62 percent in the 2014 municipal elections in Bavaria on March 16. The other parties or political groups had not nominated any opposing candidates in 2014.

For the incumbents from 1390 to 1818 see the list of mayors of Dinkelsbühl .

| Ludwig Friedrich Stobäus | mayor | 1818-1822 | ||

| Friedrich Doederlein | mayor | 1822-1828 | ||

| August Raab | mayor | 1828-1846 | ||

| August Merz | mayor | 1846-1849 | ||

| Oskar Raab | mayor | 1849-1853 | ||

| Michael Schobert | mayor | 1853-1881 | ||

| Ludwig Sternecker | mayor | 1882-1913 | ||

| Rudolf Götz | DNVP | mayor | 1913-1935 | |

| Fritz Lechler | NSDAP | mayor | 1935–1937 Deputy; 1937-1945 | |

| August Landenberger | Released from military government as executive mayor | on May 23, 1945 | ||

| Karl Ries Sen. | SPD | mayor | 1945–1952 | Appointed mayor by the American military government on May 22, 1945.

Confirmation in the local elections in 1946 and 1948. |

| Rudolf Schmidt | CSU | mayor | 1952-1961 | |

| Friedrich Höhenberger | CSU | mayor | 1961-1967 | |

| Ernst Schenk | CSU | mayor | 1967-1979 | |

| Jürgen Walchshöfer | CSU | mayor | 1979-1997 | |

| Otto Sparrer | FW | Lord Mayor | 1997-2003 | |

| Christoph Hammer (* 1961) | CSU | Lord Mayor | since November 2003 |

City council

The Dinkelsbühl city council has 24 members. The distribution of seats after the local elections in 2002, 2008, 2014 and 2020 is shown in the table below.

| year | CSU |

SPD / Independent Citizens |

Green | Free voter city | Country voter group | total |

| 2002 | 11 | 4th | 1 | 3 | 5 | 24 seats |

| 2008 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4th | 24 seats |

| 2014 | 8th | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 24 seats |

| 2020 | 9 | 3 | 4th | 5 | 3 | 24 seats |

coat of arms

| Blazon : "In red a silver three-mountain, from whose three peaks a golden ear grows." | |

The city seal of 1291 already shows a three mountain (Bühel) with ears of grain (spelled). The place name goes back to a villicus (royal court administrator) who may have been called Thingolt.

City partnerships, sponsorships, integration

The city maintains partnerships with various cities:

-

Germany : Edenkoben , Rheinpfalz

Germany : Edenkoben , Rheinpfalz -

Finland : Porvoo

Finland : Porvoo

-

France : Guérande , Loire-Atlantique department

France : Guérande , Loire-Atlantique department -

Romania : Sighișoara (Schäßburg)

Romania : Sighișoara (Schäßburg) -

People's Republic of China : Jingjiang , China

People's Republic of China : Jingjiang , China

In 1952, Dinkelsbühl took over the sponsorship of the displaced residents from the city and the district of Mies in the Sudetenland , who had to leave their homeland due to the Beneš decrees in 1945.

The city has had a partnership with the Association of the Transylvanian Saxons since May 25, 1985, which includes the Transylvanian Saxons throughout the world. The association, which at that time still operated as the Landsmannschaft of the Transylvanian Saxons, organized the first home day in the city in 1951. Since then, the meeting has taken place every year at Whitsun in Dinkelsbühl.

In 1997 the city of Dinkelsbühl was honored with the golden plaque in the national competition "Exemplary Integration of Resettlers" in recognition of the established relationships with the Association of Transylvanian Saxons and the achievements in integrating the newcomers.

There are friendly connections to the city of Schmalkalden in Thuringia.

Culture and sights

Theaters and other facilities

- State Theater Dinkelsbühl

- Dinkelsbühl jazz club

- Theater and culture ring Dinkelsbühl

- Cinema (from 2019)

Museums

- House of the Dinkelsbühl history of war and peace in the "Steinhaus" or Old Town Hall on the Altrathausplatz

- Museum 3rd dimension in the old town mill

- Historical graphic workshop

- Mies Pilsner local history museum

- Kinderzech 'armory

- Exhibition on the persecution of witches in the cellar vaults in the Dinkelsbühl House of History of War and Peace

Public venues

- Large and small Schrannenfestsaal in Schranne from 1609 with the one below

- Schrannenkeller (used weekly by the jazz club)

- Concert hall and artificial vault in the Spitalhof

- Concert hall of the vocational school for music in the Middle Franconia district

- The shielded open-air stage of the State Theater in Künßberggarten

music

The Dinkelsbühler Knabenkapelle is a historical institution of the city, comparable to a music school. Known primarily for the “ Kinderzeche ” festival , it can look back on a long tradition. “Our boys” - as they are called in the city - are between 10 and 18 years old. They are trained by local music teachers and also show their skills on tours at home and abroad. There are currently two casts available for guest performances - a large cast with around 90 musicians, divided into a drumming corps with 30 boys and a music corps with 60 boys, and a smaller cast with around 50 musicians. The repertoire ranges from classic marches and fanfares to modern jazz and pop arrangements. Today's boys' orchestra is divided into a beginner's orchestra, a B-orchestra and an A-orchestra.

Other associations:

- Dinkelsbühler Madrigal Choir

- Concordia Singers' Association 1831

- City chapel Dinkelsbühl

- Equestrian hunting horn blowers Dinkelsbühl

- Marching band owner

- D'Accord, the classical music festival

Buildings

Houses

The "European cultural monument" Dinkelsbühl includes the old town with a total of 780 houses. Of these, 77% are older than approx. 350 years, 44% and thus almost half of the houses began construction in the late Middle Ages up to approx. 1500 - an unprecedented balance in southern Germany. The occupations of house residents from around 1700 onwards have been well researched.

Historical buildings and museums

- Catholic Minster St. Georg , one of the most important late Gothic hall churches in southern Germany with a Romanesque tower portal

- Evangelical Lutheran St. Pauls Church , built 1840–1843 as a transept hall church with a gallery in the historicizing style, then called Byzantine , in place of the Carmelite monastery church on the oldest church square in Dinkelsbühl (old chapel). An architectural example of a pure form historicism. The interior was redesigned in 1992/93. A Staufer stele has stood in front of the church since October 12, 2013 .

- Baroque Carmelite monastery , secularized in 1803 and sold to the Protestant parish in 1813. Today Protestant kindergarten, Protestant parish hall and vocational school for music in the Middle Franconia district

- Capuchin monastery , built in 1622, secularized in 1803. Today a pilgrimage church.

- Former Heilig-Geist-Spital , a large monument complex, the individual buildings of which serve very different purposes today.

- Evangelical Lutheran Church of the Holy Spirit in the former Heilig-Geist-Spital, built around 1280 as a hospital church hall, around 1310 the choir and ship was expanded, around 1445 today's building. The evangelical, unique, original writing-image altar dates from 1537. After the ban on Protestant worship by the Catholic Council from 1555, the hospital church was only Protestant again from 1567. 1771–1774, the interior was redesigned into a late Rococo church with a classicist influence, with double galleries and a hollow vault. The ceiling painting, the sermon fresco “Redemption”, which is rare for a Protestant church, was made in 1774 by Johann Nepomuk Nieberlein from Ellwangen.

- Baroque Teutonic order castle with Rococo house chapel

- German house , with lush ornamental framework and carvings

- Old Town Hall (named as stone house in 1361, town hall around 1490–1855), consisting of two essentially Staufer buildings, expanded into a courtyard. Historical museum House of History Dinkelsbühl of War and Peace , witch hunt in basement rooms

- Historic town mill at Nördlinger Tor, is a unique European fortified mill , which was part of the town fortifications with the battlements. Erected from 1378–1600 on a presumed predecessor building. It houses the third dimension museum

- Kornhaus near the building yard, Kinderzech'-Zeughaus, walk-in magazine and museum of the Kinderzeche

- Cemetery of the St. Vincent Church in Segringen, listed, with uniform, black wooden crosses and gold leaf lettering

- Hezelhof: patrician house from the 16th century with a beautiful inner courtyard and three-storey wooden gallery (picture)

Wall towers and city gates of the city wall

From the east clockwise (without kennel towers):

|

|

After 1372 the construction of the extended city fortifications began. The current city wall is 2.5 km long and encloses around 33 hectares. Including the four current gate towers, it had 27 towers at times, and at least 18 kennel stands were added in the first row in front of it. The mostly disappeared outer city wall with the outer gate bastions had 13 buildings. The imperial city of Dinkelsbühl had almost 60 towers, bastions and gates at the time of the Thirty Years War. The preservation of the city wall with its gates and towers is the merit of King Ludwig I of Bavaria and his monument preservation legislation from 1826. In this way, the appearance of the old town of Dinkelsbühl was preserved. Strict building regulations such as B. the prohibition of neon advertising, a predetermined window design or the mandatory use of roof coverings in red color secure it for the future.

A historical local newspaper (so-called Urkataster, engraved in 1827) shows Dinkelsbühl in 1825.

Architectural monuments

→ List of architectural monuments in Dinkelsbühl

Segringer Gate with a baroque onion roof

Staufer column (2013)

Sport and club life

In Dinkelsbühl, there are, among other things, five rifle clubs, two sports clubs, a riding and driving club, a local group of the German Alpine Club and the KAB , a Lions Club , a Rotary Club and several music clubs.

The TSV 1860 Dinkelsbühl was founded 1860th In 1910 he planted the Hans-von-Raumer oak at Schießwasen (the location no longer belongs to Schießwasen, but opposite on Hans-von-Raumer-Straße) in memory of the founder of the gymnastics workshop in Dinkelsbühl. In 1928 he inaugurated his own hall and in 1948 a sports field. In the course of its existence, the club organized several gymnastics festivals in Dinkelsbühl. It has around 1520 members and operates 13 departments (as of early 2012).

The historical association Alt-Dinkelsbühl e. V. was founded in 1893 under the chairmanship of Mayor Ludwig Sternecker to arouse and cultivate interest in the history of Dinkelsbühl and the surrounding area by collecting and displaying old objects.

- 1894 first museum in the old town hall

- from 1899 active commitment to the preservation of the old town and the maintenance of the townscape

- 1903 Acquisition and redesign of the sexton house of the Dreikönigskapelle into a petty bourgeois house (today private)

- from 1904 historical museum in the hospital building

- In 1913, the historical association founded the periodical Alt-Dinkelsbühl under the management of former mayor Ludwig Sternecker . Messages from the history of Dinkelsbühl and its surroundings ; It appears six times a year (with interruptions) in the Wörnitz-Boten , Dinkelsbühl, since 1947 in the Fränkische Landeszeitung , Ansbach; Editor: 1913–1914 Christian Bürckstümmer , 1914–1916 Friedrich Ritter, 1916–1936 Joseph Greiner, 1937–1971 Wilhelm Reulein, 1976–2005 Hermann Maier, from 2006 Gerfrid Arnold

- from 1963 publication of a yearbook by the historical association (several years)

- 1984–1992 Development of a new overall concept (conservators Hermann Maier and Gerfrid Arnold)

- from 2004 new museum planning for the old town hall by the museum team of the association committee

- 2008 Opening of the museum "House of History Dinkelsbühl of War and Peace" with around 600 exhibits in a permanent exhibition

- 2012 Opening of the witch exhibition in the cellar vault

- 2012 Installation of the panels on the Hohenstaufen house history of the museum complex

Regular events (annually)

- Kinderzeche on the weekends before and after the third Monday in July

- City festival “Life in an old city” on the last Sunday of the Bavarian summer vacation

- Home day of the Transylvanian Saxons on Whitsun weekend in the entire old town

- German Mill Day on Whit Monday in the Hausertsmühle with a visit to the mill and a large farmers' market

- Fish harvest week around November 1st

- Christmas market in the Spitalhof during Advent

- Summer Breeze Open Air, metal festival, always on the third weekend in August in the Sinbronn district

- "Dinkelsbühl lights up", a music and culture open-air festival with evening illumination of the old town

- VR Bank Citytriathlon Dinkelsbühl, always in July, swimming in the Wörnitz, cycling and running around the historic old town.

dialect

Dinkelsbühl is located in the transition area between East Franconian and Swabian. From the east there is also the Middle Bavarian, albeit less pronounced. This results in a pronounced transitional dialect, which is reflected in the specific mixing phenomenon of the three major dialect areas as well as in certain alternation between these three dialects.

Economy and Infrastructure

Commercial structure

In today's economy, the local manufacturing companies play a dwindling, but still important, role. According to the State Statistical Office in 2004, 44 percent of employees work in the manufacturing industry, 19 percent in the tourism sector , 36 percent in the other service sector and just under one percent of those employed in agriculture and forestry. In total, with an unemployment rate of 7.2 percent, the annual average is 4461 employees subject to social security contributions. Employers were few dairies, breweries as the 1901 founded Brauerei Hauf or in the company Tucher Braeu risen Brauhaus Dinkelsbühl and the leather industry. Brush production had a center in the region. Companies came into being in the suburb of Sinbronn, among others. It was only with the expansion of the built-up area after the Second World War that there were larger production facilities in Dinkelsbühl, including plastics processing companies such as Rudolf Geitz and Esbe Plastic or the branch of Werner and Pfleiderer (industrial baking ovens ), which provide a large proportion of the jobs. Retail in the old town is still significant, but as in all cities it is on the decline. With a shopping center on Luitpoldstrasse and nine supermarkets, the central stores faced competition in the immediate vicinity. Smaller specialty shops for clothing, shoes, jewelry, stationery, drugstore supplies and optics are still available in addition to numerous service and catering establishments, as well as banking and insurance branches.

traffic

Street

Dinkelsbühl is on federal highway 25 and near the federal motorways 6 and 7 (A 6 exit Dorfgütingen, A 7 exit Dinkelsbühl / Fichtenau). The license plate was DKB. In the course of the regional reform in Bavaria , the conversion to AN took place in 1974. The DKB license plate has been available again since July 10, 2013.

railroad

During the Industrial Revolution in the second half of the 19th century came Dinkelsbuehl in a traffic geographical remoteness: The main line of the railroad from Augsburg to Würzburg was first on the Ludwig South-North Railway over Nördlingen and Gunzenhausen or that of Ingolstadt coming Altmühltal train over Ansbach to Würzburg. Later (1906) it branched off in Donauwörth in a north-easterly direction to Treuchtlingen, where it met the Altmühltalbahn and reached Würzburg via Gunzenhausen and Ansbach.

The largely straight line Nördlingen – Dombühl , which follows the Wörnitz valley to Wilburgstetten, has always remained a slow, single-track branch line along the border between the Kingdom of Bavaria and the Kingdom of Württemberg. The connection to the Ludwig-Süd-Nord-Bahn from Wassertrüdingen was originally planned, but was then carried out from Nördlingen . Construction of the Nördlingen – Dinkelsbühl line began in 1875 and operations began on July 2, 1876. At that time, the train had a journey time of 1 hour and 35 minutes on the 31 km long section. On June 1, 1881, the line was extended to Feuchtwangen . From there one could reach the railway line Nuremberg – Crailsheim near Dombühl since April 15, 1876 .

Since passenger traffic on the section between Nördlingen and Dombühl was discontinued on June 1, 1985 , only timber has been transported to a Wilburgstetten sawmill owned by the Rettenmeier company . The route from Feuchtwangen via Dinkelsbühl to Nördlingen is now operated by the Bayerisches Eisenbahnmuseum e. V. operates as a museum railway with rail buses and steam trains.

On August 2, 2012, the Bavarian State Ministry for Economics, Infrastructure and Transport announced in a press release that “a new study shows sufficiently large demand potential and, if the Bavarian uniform reactivation criteria are fully met, the Bavarian Ministry of Transport is ready to order hourly regional transport”. However, this only affects the Dombühl – Feuchtwangen – Dinkelsbühl section, as the Dinkelsbühl – Nördlingen section does not meet the demand potential according to the expert report. Local politicians are also calling for this section of the route to be reactivated.

However, the Dinkelsbühl station building had to give way to a shopping center on April 9, 2013. However, three entrances to the platform are planned, and a train stop is also to be built not far from the previous station building. The reactivation of the railway line was approved so that trains can run again soon.

After Bayernbahn did not extend the lease agreement with DB for the route from Dombühl to Wilburgstetten after 2018, there have been no museum trains since 2019.

The infrastructure company Mittelfränkische Eisenbahn-Betriebsgesellschaft MEBG was founded on March 8, 2019. This company wants to upgrade the infrastructure of the route according to the specifications of the BEG by 2024 at the latest, so that scheduled passenger train operations between Dombühl and Wilburgstetten can take place again.

Air traffic

An airfield with a 700 m long grass runway has been in operation in the Sinbronn district since 1972 . The airfield is owned by the city of Dinkelsbühl. For a symbolic amount it is donated to Aeroclub Dinkelsbühl e. V. leased, which in return takes care of operation and maintenance. For more information, see the list of traffic and special landing sites in Germany .

health

The Dinkelsbühl clinic, which is a member of the ANregiomed association, is located on Crailsheimer Straße .

education and parenting

Kindergartens

There are a total of six kindergartens in Dinkelsbühl:

- Kindergarten St. Paul (Evangelical Lutheran)

- Kindergarten Dietrich Bonhoeffer (Protestant-Lutheran)

- Flea box - group of small children (Evangelical-Lutheran)

- Kindergarten St. Georg (Catholic)

- Forest kindergarten in the Tiefweg district

- Waldorf kindergarten

schools

The following schools can be found in Dinkelsbühl and its districts:

- Vocational school for elderly care help

- Vocational school for elderly care

- Vocational school for music in the Middle Franconia district

- Vocational school for commercial assistants

- Vocational school for nursing

- Dinkelsbühl vocational school

- Christoph von Schmid Primary School in Dinkelsbühl

- Hans-von-Raumer Middle School Dinkelsbühl (Secondary School)

- Primary school Segringen

- Dinkelsbühl high school

- State Finance School Bavaria

- Special Education Center Dinkelsbühl ( Georg Ehnes School)

- Municipal music school Dinkelsbühl

- State Business School Dinkelsbühl

- Seat Academy (2019)

Dinkelsbühl as a setting in fiction and as a film set

Dinkelsbühl has repeatedly been the setting in novels and stories:

- Johann Peter Hebel : The Barber Boy of Segringen , 1809, and The Star of Segringen , 1811 (play in what is now the Segringen district )

- Ernst Kratzmann : The smile of Magister Anselmus or the life of Hanns Meinrat Maurenbrecher from Dinkelsbühl , 1927

- Loriot : Loriot's Little Book of Disasters , 1987

- Gunter Haug : The Rose of Franconia - a woman's fate in the turmoil of the Thirty Years War , 2007

In 1956, Time Stood Still, an Oscar- nominated short documentary film, was released.

Several films were shot in the old town of Dinkelsbühl, including:

- 1935/36: The Emperor of California - Germany

- 1936: The Unknown - Germany

- 1952: At the fountain in front of the gate - Germany

- 1960: Dear Augustin - Germany

- 1962: The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm - USA

- 1974: Each for himself and God against all - Germany

- 1979: The thousand and first year - Germany

- 1998: The last curtain (episode from the series “ The Crimes of Professor Capellari ”) - Germany

- 1994: SDR meeting point "Kinderzeche Dinkelsbühl"

- 1999: The Apparition - Germany

- 2003: Forever, or half a day (episode from the series “People in Bavaria”) - Germany

- 2005: SWR: Kinderzeche Dinkelsbühl (from the series "The most beautiful children and homeland festivals in southern Germany")

- 2016: SWR: Meeting point "Kinderzeche Dinkelsbühl"

The second of seven pictures of the operetta Doctor Eisenbart takes place on the market square of Dinkelsbühl: "Dinkelsbühl Fair".

Personalities

Others

The world of legends in Dinkelsbühl

More than 50 sagas, legends and haunted stories have been handed down since the 16th century, the first being the nickname "Sichelschmied" for the people of Dinkelsbühl, who were known for their scythes and sickles of high quality throughout southern Germany. The oldest written collection dates from 1863, the high time of the Dinkelsbühler saga collectors was in the first third of the last century.

The nicknames of the Dinkelsbühlers

- Blue boiler

Legend has it that the town councilors discussed the appropriate punishment for the act of a robber. The debate supposedly lasted a very long time, one of the councilors nodded off and dreamed of lunch that he had recently had, a blue-boiled Wörnitz carp. When it came to the vote on the punishment, he was woken up by his council neighbor and, drowsy, said: "You should boil him blue!"

Since then the Dinkelsbühler have been called blue boilers . A 400-year-old "Türgucker" (little door in the front door) in the House of History, which shows a sleeping fisherman, also bears this nickname. This legend was only ascribed to the Dinkelsbühlers by the historical association at the turn of the last century.

- Moon splash

In the Biedermeier period, the tower guard of St. Georg once sounded the alarm at night with the fire bell . When the fire brigade and the citizens rushed to the alleged scene of the fire, the moon rose large and round behind the roof of the house.

literature

- Alt-Dinkelsbühl. Messages from the history of Dinkelsbühl and its surroundings. Appears as a supplement to the “Fränkische Landeszeitung” . Periodical since 1913 in the Wörnitz-Boten , with interruptions.

- Gerfrid Arnold: Dinkelsbühl. A medieval city . Verlag am Roßbrunnen Hanns Bauer, Dinkelsbühl 1988.

- Gerfrid Arnold: Because of the Schulzech children. The Dinkelsbühl collieries in the imperial city period . Publisher Hanns Bauer, Dinkelsbühl 1994.

- Gerfrid Arnold: Chronicle Dinkelsbühl . Volume 1: Early Period – 1024. In the empire of the Merovingians, Carolingians and Saxons. Books on Demand , 2000.

- Gerfrid Arnold: Chronicle Dinkelsbühl . Volume 2: 1024-1273. The royal city. Salier-Staufer Interregnum. Books on Demand, 2001.

- Gerfrid Arnold: Chronicle Dinkelsbühl . Volume 3: 1273-1369. The imperial city. From King Rudolf I to Emperor Karl IV. Books on Demand, 2002.

- Gerfrid Arnold: Chronicle Dinkelsbühl . Volume 4: 1370-1400. The city republic. Emperor Karl IV. And King Wenzel I. Books on Demand, 2003, ISBN 3-8311-4899-6 .

- Gerfrid Arnold: Chronicle Dinkelsbühl. Volume 5: Walls and Towers. The city fortifications from the royal court to the 21st century. Books on Demand, 2014, ISBN 978-3-7386-0121-3 .

- Gerfrid Arnold: Christmas in Dinkelsbühl with CvS Dinkelsbühl for kids. Reading city guide. Books on Demand, 2004, ISBN 3-8334-1427-8 .

- Gerfrid Arnold: Holidays in Dinkelsbühl . Dinkelsbühl for kids. Reading city guide. Books on Demand, 2005, ISBN 3-8334-3204-7 .

- Gerfrid Arnold: Ghost tour in Dinkelsbühl . Dinkelsbühl for kids. Reading city guide. Books on Demand, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8334-8194-9 .

- Gerfrid Arnold: Witches and Wizards in Dinkelsbühl . Books on Demand, 2006, ISBN 3-8334-5355-9 .

- Gerfrid Arnold: Witches, wizards and devil banners not executed in the imperial city of Dinkelsbühl in the 17th century . In: Alt-Dinkelsbühl. Supplement to the Fränkische Landeszeitung , 2013, pp. 9–26.

- Gerfrid Arnold: Jews in Dinkelsbühl . Ed. Historical Association Alt-Dinkelsbühl e. V., 2010.

- Gerfrid Arnold: The series archive images. Dinkelsbühl. People, pictures, impressions . Sutton Verlag, Erfurt 2011, ISBN 978-3-86680-816-4 .

- Walter Bogenberger: History of the city of Dinkelsbühl. In: Walter Bogenberger, Michael Vogel: Dinkelsbühl. 1983, pp. 5-31.

- Peter Breitling u. a .: Old city - today and tomorrow. Bavarian State Ministry of the Interior, Munich 1979.

- August Gebeßler: Dinkelsbühl. ( Deutsche Lande - German Art ). Munich / Berlin 1962.

- August Gebeßler : City and district of Dinkelsbühl (= Bavarian art monuments . Volume 15 ). Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 1962, DNB 451450930 .

- Karl Heinrich von Lang , Heinrich Christoph Büttner , Knappe: District Court Dinkelsbühl (= historical and statistical description of the Rezatkreis . Issue 2). Johann Lorenz Schmidmer, Nuremberg 1810, OCLC 165619678 , p. 3-19 ( digitized version ).

- Wolf-Armin von Reitzenstein : Lexicon of Franconian place names. Origin and meaning . Upper Franconia, Middle Franconia, Lower Franconia. CH Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-59131-0 , p. 54-55 .

- Gustav Roeder: Dinkelsbühl . In: Wolfgang Buhl (Hrsg.): Franconian imperial cities . Echter, Würzburg 1987, ISBN 3-429-01098-5 .

- Anton Steichele (Ed.): The diocese Augsburg historically and statistically described . tape 3 . Schmiedsche Verlagbuchhandlung, Augsburg 1872, p. 249-318 ( digitized version ).

- Pleikard Joseph Stumpf : Dinkelsbühl . In: Bavaria: a geographical-statistical-historical handbook of the kingdom; for the Bavarian people . Second part. Munich 1853, p. 666-667 ( digitized version ).

- Teresa Neumeyer: Dinkelsbühl . The former district (= Historical Atlas of Bavaria, Part I francs . Band 40 ). Commission for Bavarian State History, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-7696-6562-8 ( limited preview in Google book search).

Web links

- Map of the city of Dinkelsbühl on the BayernAtlas of the Bavarian State Government ( information )

- City administration of Dinkelsbühl

- Dinkelsbühl: Official statistics of the LfStat

- City tour through Dinkelsbühl

Individual evidence

- ↑ "Data 2" sheet, Statistical Report A1200C 202041 Population of the municipalities, districts and administrative districts 1st quarter 2020 (population based on the 2011 census) ( help ).

- ↑ City Council. City administration Dinkelsbühl, accessed on June 7, 2020 .

- ^ Fifth law to change the structure of municipalities and administrative communities of July 26, 1997 ( GVBl , p. 309)

- ^ Community Dinkelsbühl in the local database of the Bavarian State Library Online . Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, accessed on September 17, 2019.

- ↑ a b c Joachim Kolb: Dinkelsbühl: Development and Structure , Munich 2009, p. 4.

- ↑ Dinkelsbühl: Historical overview . City of Dinkelsbühl. Archived from the original on March 23, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ Peter Koblank: Errata of the Stauferstelen on stauferstelen.net. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- ↑ W.-A. v. Reitzenstein, p. 54 f.

- ↑ Alphabetical index of all the localities contained in the Rezatkkreis according to its constitution by the newest organization: with indication of a. the tax districts, b. Judicial Districts, c. Rent offices in which they are located, then several other statistical notes . Ansbach 1818, p. 111 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Gerfrid Arnold : Witches and Witches in Dinkelsbühl, documentation for the exhibition in the Rothenburg gate tower Witches and Witches in Dinkelsbühl , Dinkelsbühl, 2006, ISBN 3-8334-5355-9 .

- ↑ Gerfrid Arnold: Not executed witches, wizards and devil banners of the imperial city of Dinkelsbühl in the 17th century. In: Alt-Dinkelsbühl - Messages from history, 2013, pp. 9–26.

- ↑ Birch semolina hammer: Dinkelsbühl . In: Hexen-Franken.de , 2013

- ↑ hexen-franken.de: Dinkelsbühl

- ↑ Traudl Kleefeld: Against forgetting. Witch persecution in Franconia - places of remembrance. J. H. Röll, Dettelbach 2016. P. 52 ff.

- ^ Gerfrid Arnold: Origin and decline of the Evangelical Lutheran state church in the imperial city of Dinkelsbühl. In: Alt-Dinkelsbühl . 2005, pp. 33-48

- ^ Homepage of the Catholic parish community in Nördlingen . Catholic parish community Nördlingen. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ↑ http://www.dekanat-dinkelsbuehl.de/dekanatdkb/

- ^ Religious affiliation of the population of Dinkelsbühl . Bavarian State Office for Statistics and Data Processing. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ↑ https://results.zensus2011.de/#dynTable:statUnit=PERSON;absRel=PROZENT;ags=095710136136;agsAxis=X;yAxis=RELIGION_AUSF

- ↑ Gerfrid Arnold: Dinkelsbühler Altstadthäuser - Apartments of Jewish fellow citizens from the Thirty Years War in 1636 to the forced emigration by the pogrom in 1938. In: Alt-Dinkelsbühl - Mitteilungen aus der Geschichte, 2018.

- ^ Gerfrid Arnold: Jews in Dinkelsbühl . Historical Association Alt-Dinkelsbühl e. V. 2010 and Barbara Eberhardt: Dinkelsbühl, in: KRAUS, WOLFGANG / BERNDT HAMM / MEIER SCHWARZ (eds.): More than stones. Synagogue Memorial Volume Bavaria, Volume II - Developed by Barbara Eberhardt and Angela Hager, Lindenberg / Allgäu (2010), 175-179.

- ↑ Quoted in: Obama remembers Jews from Dinkelsbühl. A very well attended event on the night of the pogrom, in: Sonntagsblatt. Evangelical weekly newspaper for Bavaria No. 47 of November 23, 2014, p. 13. URL: http://www.sonntagsblatt-bayern.de/news/aktuell/2014_47_anw_13_01.htm (accessed January 12, 2015). For the English-language original see http://www.alemannia-judaica.de/dinkelsbuehl_synagoge.htm (accessed January 12, 2015).

- ↑ Dieter Reinhardt: About "stumbling blocks" against forgetting . In: Fränkische Landeszeitung No. 260 from November 11, 2014 (section Ansbach district), accessed June 11, 2018.

- ↑ Obama commemorates Jews from Dinkelsbühl. A very well attended event on the pogrom night . In: Sunday paper. Evangelical weekly newspaper for Bavaria , No. 47 from November 23, 2014, p. 13, accessed June 11, 2018.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Wilhelm Volkert (Ed.): Handbook of the Bavarian offices, communities and courts 1799–1980 . CH Beck, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-406-09669-7 , p. 448 .

- ↑ a b Federal Statistical Office (ed.): Historical municipality register for the Federal Republic of Germany. Name, border and key number changes in municipalities, counties and administrative districts from May 27, 1970 to December 31, 1982 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart / Mainz 1983, ISBN 3-17-003263-1 , p. 707 .

- ↑ Development of the population of the city of Dinkelsbühl . City of Dinkelsbühl. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ↑ Development of the population of the city of Dinkelsbühl . Bavarian State Office for Statistics and Data Processing. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ↑ Maximilian Mattausch: Dinkelsbühl's Mayor Sternecker and his time. Customs care Dinkelsbühl e. V., 2009, ISBN 978-3-8370-3021-1 .

- ↑ Development of the population of the city of Dinkelsbühl . www.ulischubert.de. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ^ Michael Rademacher: German administrative history from the unification of the empire in 1871 to the reunification in 1990. City and district of Dinkelsbühl. (Development of the population of the city of Dinkelsbühl; online material for the dissertation, Osnabrück 2006).

- ↑ Information on mayors of Dinkelsbühl up to the 18th century ( Memento from May 4, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Information on the mayors of Dinkelsbühl in 20./21. Century ( Memento from July 11, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c d e f Joseph Greiner: Dinkelsbühl. Publishing house Paul Schön, Dinkelsbühl, no year

- ^ Messages from the history of Dinkelsbühl and its surroundings . Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ Territorial changes in Germany and German administered areas 1874–1945 . Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ History of the SPD Dinkelsbühl . Archived from the original on November 28, 2012. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ↑ Festschrift for the 100th anniversary of the Dinkelsbühl local association of the SPD (PDF; 2.2 MB) Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved on January 1, 2011.

- ↑ http://www.wahlen.bayern.de/kommunalwahlen/

- ↑ https://www.dinkelsbuehl.de/deutsch/alle/stadt-dinkelsbuehl/partnerstaedte-patenschaften

- ↑ 25 years of partnership between Dinkelsbühl and the Association of Transylvanian Saxons

- ↑ Award of the city of Dinkelsbühl with the golden plaque in the national competition "Exemplary integration of the resettlers" ( Memento from June 22, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Gerfrid Arnold: Dinkelsbühler Hauslexikon AH. Architecture-residents-history-saga. 2016; IM 2017; NR 2018

- ↑ Gerfrid Arnold: The St. Paul's Church in Dinkelsbühl . In: Evangelical churches in Dinkelsbühl . DKV Art Guide No. 667, 2011, pp. 26–39.

- ↑ Stauferstele Dinkelsbühl on stauferstelen.net with historical background information (accessed on March 22, 2014)

- ↑ Gerfrid Arnold: The Last Supper Altars in Heiliggeist and St. Georg from 1537. Two text-image altars of the early Protestant altar architecture in Dinkelsbühl . In: Alt-Dinkelsbühl. 2011, pp. 18–24

- ↑ Gerfrid Arnold: Johann Nepomuk Nieberlein's sermon fresco “Redemption” in the Evangelical Church of the Holy Spirit in Dinkelsbühl . In: Alt-Dinkelsbühl. 2011, pp. 41-48; ders .: The Heiliggeistkirche in Dinkelsbühl . In: Evangelical churches in Dinkelsbühl . DKV Art Guide No. 667, 2011, pp. 3–25

- ↑ Gerfrid Arnold: From the Stauferburg to the House of History Dinkelsbühl . In: House of History Dinkelsbühl of War and Peace . Historical association Alt-Dinkelsbühl. Festschrift, 2008, pp. 93–112

- ↑ Arnold, Gerfrid: The town mill in Dinkelsbühl - unique fortified mill (1378-1600) . In Alt-Dinkeslbühl . 2013, pp. 27–32.

- ^ Gerfrid Arnold: Dinkelsbühl. A medieval city . 1988, pp. 75-85; ders .: White Tower and Dönersturm - two Dinkelsbühl wall towers . In: Alt-Dinkelsbühl . 2002, pp. 9-14

- ^ Gerfrid Arnold: Chronicle of Dinkelsbühl. Vol. 5, walls and towers, city fortifications from the royal court into the 21st century, p. 146 ff. Books on Demand, 2014.

- ↑ local Journal of Dinkelsbühl 1827 . Bavarian State Library, Munich. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ↑ Heinz Stark: My gymnastics club - my TSV 1860 Dinkelsbühl from 1860 to 1877. In: Alt-Dinkelsbühl. 2010, pp. 9-16; Ders .: 1876 to 1903. ibid. 2011, pp. 25–31; Ders .: 1903 to 1926. ibid. 2012, pp. 17-24.

- ↑ www.tsv-dkb.de

- ^ Hermann Maier: The historical association in Dinkelsbühl. A look back at 100 years of club history. In: Yearbook 1991–1993 for the 100th anniversary of the association, pp. 10–38. Gerfrid Arnold: 100 years of the club collection. In: ibid, pp. 40-64.

- ↑ https://www.romantisches-franken.de/poi/detail/5b042c3d975a8c326d197233

- ↑ Fishing week in Dinkelsbühl. Retrieved December 17, 2010 .

- ↑ Cf. Neu, David: One speaker - several dialects: code mixing and code switching in the tridialectal space around Dinkelsbühl. Published online at urn: nbn: de: bvb: 824-opus4-2153 or http://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-ku-eichstaett/frontdoor/index/index/docId/215

- ↑ There is no big rush in the Ansbach district . Bavarian radio. Archived from the original on February 26, 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ August Gabler: One hundred years of the Nördlingen – Dinkelsbühl railway. In: Alt-Dinkelsbühl. 1977, pp. 41-47.

- ↑ Bavarian Railway Museum e. V.

- ^ Hessel: "Good chances for BAYERN-TAKT to Feuchtwangen and Dinkelsbühl" ( Memento from April 19, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Dombühl – Dinkelsbühl – Nördlingen - an almost forgotten railway line

- ↑ Middle Franconian Railway Company. Accessed August 30, 2020 .

- ↑ Welcome to the website of Christoph Himsel. Retrieved March 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Overview of the kindergartens . City of Dinkelsbühl. Archived from the original on November 20, 2010. Retrieved on December 13, 2010.

- ↑ Overview of the schools . City of Dinkelsbühl. Archived from the original on November 20, 2010. Retrieved on December 13, 2010.

- ^ Vocational schools for nursing professions Dinkelsbühl . Vocational schools for nursing professions Dinkelsbühl. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ^ Dinkelsbühl vocational school for music . Vocational school for music. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ^ State vocational school Rothenburg-Dinkelsbühl . State vocational school in Rothenburg. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ↑ Dinkelsbühl primary school . Dinkelsbühl primary school. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ↑ Hans-von-Raumer Middle School . Hans-von-Raumer Middle School. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ↑ Segringen primary school . Primary school Segringen. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ↑ Dinkelsbühl high school . Dinkelsbühl high school. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ↑ Georg-Ehnes-Schule special educational support center . Dinkelsbühl support center. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ↑ Dinkelsbühl Municipal Music School . City of Dinkelsbühl. Archived from the original on December 15, 2010. Retrieved on December 20, 2010.

- ↑ Dinkelsbühl Business School . Business School Dinkelsbühl. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ↑ Gerfrid Arnold: Dinkelsbühler Sagenwelt - Spukgeschichten from Pankraz Dumpert's "Promemoria" 1863 . In: Alt-Dinkelsbühl. 2011, pp. 13-16; Ders .: Behind the devil's wall. Legends, spooks and legends between Dinkelsbühl and Wassertrüdingen . 1999, pp. 22-98 and Appendix pp. 234-243; Ders .: Ghost tour in Dinkelsbühl. Dinkelsbühl for kids. Reading city guide . Books on Demand, 2007.

- ↑ Anecdote: The Dinkelsbühler blue boilers . Romantic Franconia Tourist Association. Retrieved April 23, 2012.