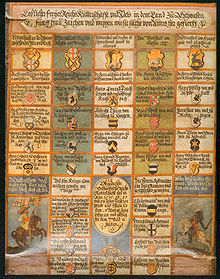

List of Swabian noble families

Particularly highlighted in the 17th century :

Duchy of Württemberg

The margravates of Baden and Burgau

The counties of Öttingen, Rechberg, Königsegg, Hohenzollern, Fürstenberg

The barons of Limpurg, Waldburg, Justingen

The house of Fugger

The bishops of Augsburg and Constance and the Kempten abbey

The city of Ulm

List of noble families from the Swabian area .

Quick reference:

introduction

The territorial fragmentation of southern Germany in the Old Kingdom with its many imperial-direct territories is difficult to grasp in standard historical works. As a rule, even the regional history is concentrated in the nearby large territories, Baden , Württemberg , and Hohenzollern .

It is common today to think in terms of territoriality. In the historical context, such nation-state thinking is still quite new. Until the end of the monarchy, however , the inhabitants of a territory were not Baden, Württemberg or Prussian, but subjects of the respective sovereign and in the event of death or change of rule the new sovereign had to be paid homage to. The feudal fief system made things even more complicated. At least until the end of the old empire , it was the sole privilege of the “Roman” king or emperor to admit someone to the nobility. The nobleman could dispose of so-called allodial property , or received property as fief. He could in turn have received this fiefdom directly from the king or emperor, or, and this applies above all to less powerful noble families, from a secular or spiritual prince. The rulers established as a result were not exclusively defined in terms of territory, but were largely a mutual, personal relationship. It was manorial rule and corporal rule , from which tax obligations and compulsory labor of the subjects grew. Serfdom also restricted the freedom of movement of the subjects. Other possible rights were the right to collect, i.e. the right to raise taxes, the sovereignty of defense and the right of patronage . Furthermore, the exercise of higher and lower jurisdiction was important both as a power factor and as a source of income . Such rights or property also changed hands in the form of inheritance, dowry or pledge, and in particular manorial and bodily rule could be related to individual residents within a village from different noble families. Another right of rule that often led to conflicts - also between different noble families - was the right to hunt. For the subjects this was particularly important because of the hunting fron and the damage caused by game .

The historical development led to the development of a special aristocratic landscape in the area of the former Duchy of Swabia , in which - unlike in Bavaria, for example - no larger territorial state was able to subjugate the inferior noble families to residency. In this landscape, a large number of imperial monasteries were able to maintain their independence and, at least until the early modern period, represented a field of activity for the lower nobility. The occupation of the principal bishoprics was, at least in the area under consideration, apart from the early years, also the lower Nobility reserved.

Therefore, the noble families and not the territories are recorded here. The time frame should be limited by the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss . The spatial framework is given by the Swabian Circle , or by the extent of the former Duchy of Swabia . This regional demarcation is justified because it corresponds to a grown structure of a common origin felt by the members of this group.

Since the noble families were subject to increases in rank, but sometimes also to reductions in rank, no differentiations are made here between high and low nobility genders. A record is made if a clear assignment is possible via literature or coats of arms of local coats of arms and gender coats of arms.

The non-princely aristocratic houses formed a cooperative to form noble societies. These were more than just tournament companies. These were protective alliances against both the cities and the princes. In addition, they served to settle internal conflicts through arbitration. Against the threat to their interests in the Appenzell Wars, the aristocrats united in the supra-regional alliance of the Sankt Jörgenschild . This time, the members of the Sankt Jörgenschild in the Swabian Federation were united with princes and cities as the first cross-class peace alliance . This alliance served as a model for further imperial reform . The organizational structure of the federal government was adopted. After the failure of the imperial reform, the district division was retained, but the lower aristocratic noble families, who were able to retain their imperial immediacy, united in the imperial knighthood. Within the district order, which they also adopted for themselves, they also linked to the traditions of the noble societies and adopted their symbolism. The cantons adopted the emblems of the societies previously represented in these cantons: for example, the knightly canton of Hegau-Allgäu-Bodensee the fish and the falcon, or the knightly canton Kraichgau, the heraldic animal of society with the donkey .

See also

- List of Gaue of Alamannien / Swabia, Alsace and Hochburgund

- Duchy of Swabia

- List of Frankish knight families

- List of Bavarian noble families

literature

- Otto von Alberti (term): Württemberg nobility and coat of arms book. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1889–1916 ( digitized version )

- Karl S. Bader: The German southwest in its territorial state development . Stuttgart 1950.

- Casimir Bumiller (Ed.): Adel im Wandel; 200 years of mediation in Upper Swabia . Exhibition catalog for the exhibition in the Prinzenbau and Landeshaus Sigmaringen. tape 1 : Nobility in transition - 200 years of mediatization in Upper Swabia . Jan Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2006, ISBN 3-7995-0216-5 .

- Mark Hengerer, Elmar Kuhn (Hrsg.): Adel im Wandel; Upper Swabia from early modern times to the present . Attachment tape. tape 2 . Jan Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2006, ISBN 3-7995-0216-5 .

- Casimir Bumiller: History of the Swabian Alb. From the ice age to the present . Casimir Katz Verlag, Gernsbach 2008, ISBN 978-3-938047-41-5 .

- Gerhard Köbler : Historical lexicon of the German countries. The German territories from the Middle Ages to the present. 7th, completely revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-54986-1 .

- Pleickhard von Helmstatt: Family trees of southern German noble families . In: Digital Collections Darmstadt . HS-1970. University and State Library, Darmstadt ( tudigit.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de [accessed on August 17, 2012] around 1612, additions from the 17th and 18th centuries).

- Gustav A. Seyler: The dead Württemberg nobility (= J. Siebmacher's Wappenbuch. VI, 2). Nuremberg 1911 ( digitized version ).

Web links

- Historical Atlas of Bavaria: Part of Swabia

- Compilation: Swabian nobility of the Foundation for Medieval Genealogy

Individual evidence

- ↑ Monika Spicker-Beck : Nobility in Upper Swabia at the end of the Old Kingdom . In: Aristocracy in Transition 200 Years of Mediatization in Upper Swabia . Exhibition catalog. Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2006, ISBN 3-7995-0216-5 , p. 17-29 .

- ↑ Historical Lexicon of Bavaria: Imperial Pencils in Swabia (Sarah Hadry)