Horbourg Castle

| Horbourg Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | unknown |

| limes |

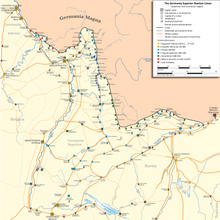

Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes , Maxima sequanorum |

| Dating (occupancy) |

Late 4th century to early 5th century |

| unit | a) Legio I Martia ? b) Limitanei ? c) Comitatenses ? d) Foederati ? |

| size | approx. 2.6 ha |

| Construction | Stone construction |

| State of preservation | Not visible above ground, square system with corner and intermediate towers and four gate towers. |

| place | Horbourg-Wihr |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 4 '47 " N , 7 ° 23' 46" E |

| height | 190 m |

| Previous | Fort Sasbach-Jechtingen (north / right bank of the Rhine) |

| Subsequently | Fort Oedenburg-Bisheim (southeast / right bank of the Rhine) |

| Upstream | Mons Brisiacus |

Fort Horbourg was a late antique fortification on the area of today's Horbourg-Wihr ( German Horburg-Weier , Alsatian Horwrig-Wihr ) an Alsatian community in the French department of Haut-Rhin , Arrondissement Colmar-Ribeauvillé , canton Andolsheim .

The late antique camp of Horbourg occupied a key position in the defense of the Rhine hinterland in the 4th and 5th centuries and, together with the crews of the forts in Biesheim-Oedenbourg , Sasbach-Jechtingen and Breisach, controlled the thoroughfares to the Rhine border. The archaeological site of Horbourg-Wihr includes the remains of a Gallo-Roman civil settlement from the 1st century and those of a late Roman fort from the 4th century, from which important relics from Alsace in Roman times could be recovered. The different stages of the excavations also illustrate the development of archeology from a mere hobby of some interested amateurs to a professional discipline.

location

Horbourg is about three kilometers east of the city center of Colmar . The fort and the civil settlement were located at the confluence of the Thur with an oxbow of the navigable Ill and were built on a 4 m high alluvial terrace, protected from flooding, which formed a kind of peninsula. The terrace was surrounded by mostly swampy terrain, through which the watercourses of the Leek and Fecht flowed. The border line between the two provinces Germania I and Maxima Sequanorum ran north of the Kaiserstuhl . There was a road along this line that reached the banks of the Rhine at Bisheim-Oedenburg via the Vosges and Metz. Here it subsequently crossed with the Limesstrasse on the left bank of the Rhine, running from north to south.

Surname

Since the 16th century it was believed that the Roman Horbourg was identical to the Argentovaria - mentioned in several ancient sources . This place name is used in several ancient manuscripts - such as B. by the geographer Ptolemy - mentioned in the 2nd century. Other manuscripts from the 3rd and 4th centuries ( Tabula Peutingeriana ) also attest to the existence of Argentovaria . Today, however, the general opinion is that it was a Roman civil settlement or a fort near Biesheim built over its ruins in the 4th century . Since no ancient inscription in this regard has so far appeared that could finally clarify this, this question remains unanswered. The place name in use today is probably due to the topographical conditions. The "Horoburc" known since the Middle Ages can be translated as "Castle in the Swamps".

development

The settlement of Alsace goes back to the Neolithic (10,000 BC). Around 58 BC BC Caesar's legions defeated the Germanic army king Ariovistus at Mulhouse and threw him back across the Rhine. Since then, Alsace has been part of the Roman Empire. At the end of the 1st century AD, after the occupation of the Agri decumates (so-called Dekumatenland ) , the border of the empire was brought forward to the newly established Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes . For the next 200 years, Alsace was part of the Limes hinterland. Most of the findings from Horbourg-Wihr attest to Roman settlement activities during the 1st, 2nd and 4th centuries. The first Roman settlement was founded at the beginning of the 1st century. The heyday of the civil settlement falls in the late 1st century. At the end of the 2nd century economic activity decreased drastically and people obviously started to leave the settlement again. The reasons for this could have been the increasing floods as a result of climate change and the first major forays of the Germanic peoples.

In the 3rd century the pressure of the “barbarian people” on the right bank of the Rhine on the Rhine Limes increased. The Alamanni and their allies devastated the Rhine provinces several times (235, 245, 260, 356, 378) and probably also the vicus of Horbourg, which had already been badly affected , and which had to be finally given up by its inhabitants. After the withdrawal from the Upper German-Rhaetian Limes and the relocation of the imperial border back to the Rhine ( Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes ) in 259/260, a fort was built to secure the strategically important road junction in Horbourg. During the great barbarian incursions in the 4th and 5th centuries it was probably part of a fortress belt, which also included the forts on the right bank of the Rhine on the Münsterberg in Breisach and on the Sponeck in Sasbach-Jechtingen . In 378 Emperor Gratian defeated the Alemannic Lentiens near Argentovaria and pushed them back across the Rhine. The Roman border defense almost completely collapsed in the winter of 406/407 .

The camp was likely abandoned by the Romans in the early fifth century. It could have been destroyed by the Vandals , Alans or Suebi when they breached the border in winter 406/407 or by the Huns when they migrated to Gaul in 451. The Alamanni then began to settle in the areas to the left of the Rhine, which were only nominally under Roman sovereignty. In the battle of Zülpich in 496 and in further battles in 506, the Frankish king Clovis I defeated the Alamanni and ended their rule over the former Rhine provinces. A possible reuse of the fort in the High Middle Ages is poorly documented and has remained controversial to this day.

Research history

Due to the continuous settlement of the place and its strategically important position, the fort square has been plagued by wars and invasions over the centuries. The interpretation of the excavation findings has therefore not always been easy. The dense modern construction of the site prevents it from being fully exposed to this day.

The earliest reports of Roman finds date from 1543 and were made during the expansion of the castle of the Counts of Württemberg. The fortress cut exactly the northeast corner of the camp. They were written by the humanist Beatus Rhenanus , who mentions the discovery of the ancient walls in a chronicle. He suspected that it was the remains of Argentovaria and sparked a vigorous controversy among scientists that continues to this day. An Apollo Grannus altar was discovered in 1603, but was lost again when the city library of Strasbourg was destroyed by flames in 1870.

Around the middle of the 18th century, Johann Daniel Schoepflin researched the ancient place name and collected related articles in his Alsatia Illustrata . In 1748 another Roman altar was salvaged by a Protestant pastor. 1780–1784, Sigismund Billing, Rector of Colmar, discovered the remains of the fort, a relief and an ancient tomb for the first time.

In the 1820s, the judge Philippe de Golbery wrote a first monograph on the Roman Horbourg. The first systematic excavations were carried out by the pastor Emile Alphonse Herrenschneider and the building officer Charles Winkler from 1884 to 1899 and the results were published. Despite the limited space that was available, this excavation work was the basis for the creation of a detailed plan of the fort, which is still valid today. The artifacts found during this first excavation campaign mostly disappeared in private collections.

While new techniques were used and more systematic rescue excavations were carried out during the 20th century, rapid urbanization left many artefacts irretrievable. From 1964 Charles Bonnet and Madeleine Jehl excavated in Horbourg (6 m² area - 4 m deep) and proved the existence of a vicus from the 1st century AD, which preceded the fort. 1971–1972 you came across part of the eastern fort wall, which had been badly damaged during the construction of the medieval castle. In 1991 the archaeological and historical society ARCHIHW (see web links) was founded to monitor and maintain the archaeological sites in Horbourg. Between 1989 and 1994, new investigation techniques - such as z. B. geophysical prospecting - applied. The remains of ancient melting and kilns, tombstones and coins were recovered. In 1996 a section of the very well-preserved foundations of the western wall was exposed.

The south gate of the camp was discovered in 2004 and further parts of the fort wall were discovered during construction work in 2010. In 2011 the moat in front of the west gate could be observed.

Road links

The fort and vicus were probably located in the center of a network of roads and canals that led in a star shape in all directions and as far as the Rhine border. However, to this day, knowledge of the local ancient roads is extremely limited. Since the 17th century, researchers tried, more or less successfully, to reconstruct the course of Roman roads in the vicinity of Horbourg. To date, this has only partially succeeded. A distinction between simple paths and paths or roads of primary importance was also not possible.

One of these paths ran past today's Horbourg cemetery to the west and then probably led further north. It was discovered in the 19th century and in 1992 archaeologists could still trace it for a few hundred meters. Its function in the Roman road network is unclear. It was not possible to determine whether it was just an access route to the vicus , or whether it led either to the Illhafen or further north. In 1994 a road to the east was discovered that led directly to Argentovaria / Biesheim - Oedenbourg. There should also be a western counterpart to this road, in the direction of the Vosges.

At the end of the 19th century, Pastor Herrenschneider reports on the discovery of a Roman canal that led south from the fort. However, he gave no information about its exact function.

Another road to the north-east led from Horbourg-Wihr to Jebsheim and from there to the banks of the Rhine. Part of it could also be observed in a suburb in 2008. The marshland could be crossed comfortably and safely on a road that led directly past the fort. On it one subsequently reached the Rhine crossing at Fort Breisach .

Fort

The fort stood in the center of the former vicus and was encircled by two branches of the river to the west and east. Due to the lack of major excavation campaigns, little is known about the exact location and appearance of the fort. It was probably very similar to the forts in Alzey and Bad Kreuznach, presumably had a ground plan in the form of a 168.5 m × 160 m regular square and covered an area of around 2.6 hectares. It was a very large fort for this period. The fence consisted of Vosges sandstone and was additionally protected outside by a ditch filled with water. There were four round corner towers at each of the corners, with eight semicircular intermediate towers in between. The fort probably had four square gate towers with a passage that were centrally located in the north, south, west and east. Otherwise only an early Christian church from the 6th to 7th centuries and a cemetery are attested in the center of its area.

The question of the dating of the camp has not yet been fully clarified. Modern scholars suspected that it had been laid out in the time of Augustus . Between 1820 and 1830, Philippe Golbery et al. a. from the discovery of a dedicatory inscription by Geta , but assumed that the camp was only built during the re-fortification of the Rhine border under the rule of the Caesar of the western half of the empire, Julian the Apostate . Herrenschneider and Winkler dated the fort in the third century AD. In 1918, Robert Forrer drew attention to the great similarity of the camp with the much more extensively researched Fort Alzey , as did Charles Bonnet in 1964–1972. According to the evaluation of the investigation results from 1996, the fort is likely to have been built in the late fourth century - more precisely between 330 and 370.

garrison

It is not known which unit of the Roman army provided the fort's guards. The camp was probably - as usual for the 4th and 5th centuries - with Limitanei / Ripenses or - due to its time position even more likely - with Germanic Foederati (allies), which was probably assigned to the commander responsible for this border section, the Dux provinciae Sequanicae , were subject. It is also conceivable that, due to its size, the fort was primarily used as a base for deployments by the mobile field army ( Comitatenses ) .

The most important written source for the assignment of late antique border troop units and fort names of the 4th and 5th centuries is the Notitia Dignitatum . In it, however, neither the place name of the Horbourger fort nor its garrison unit or its commanding officer are given. Only the Legio I Martia is documented by numerous brick stamps in the first half of the 4th century as a border guard on the Upper Rhine. Vexillations of her stood u. a. in the camps of Windisch, Kaiseraugst, Breisach and Oedenburg-Biesheim. At the end of the 19th century Herrenschneider also hid some of their brick stamps in Horbourg.

In the antiquities collection of the Colmar-Unterlinden museum there are also two brick stamps of the Legio VIII Augusta from Strasbourg, which were allegedly also found in Horbourg. However, it is doubtful whether they actually come from there.

Civil settlement

On the area of the civil settlement there were also some references to pre-Roman life based on artifacts from the late Bronze Age . An inscription that has been known since 1816 shows that the fort was built over the ruins of the civil settlement (vicus) populated by Gallo-Romans . However, the inscription did not contain any indication of what legal status it had. It was probably a larger settlement of the Celtic Raurics , whose metropolis was Augusta Raurica (Kaiseraugst).

Presumably it covered an area of around 50–80 hectares and was made in the early 1st century AD. Excavations in the Rue des Ecoles (1998–1999) revealed the earliest finds from the years between 20 and 40 AD. It is possible that Roman soldiers were stationed here from this point in time. How many people lived here is not known. There are only indications of their economic and craft activities. In the area of the new town hall, the remains of a metal foundry were observed in 1993 and also those of workshops in 2008–2009. At the end of the 1st century the settlement had evidently grown to a considerable size and became a regional center of trade and handicrafts.

In the first third of the 2nd century it reached its greatest extent, as the archaeological layers from this period show. The buildings had been erected with great care and had arcades facing the street that covered the sidewalk. Apparently the inhabitants had achieved considerable prosperity and the Roman way of building had largely prevailed. Most of the buildings were still made of wood and clay. Little is known about the road network of the Vicus.

In the center of today's city (Jardin Ittel - Rue des Ecoles), Pastor Herrenschneider discovered a larger building in 1884, the masonry of which had been very carefully executed. The excavator thought it was the praetorium of the late Roman camp. Subsequent excavations in 2004 revealed that it was built between 180 and 220 AD and was surrounded by a colonnade ( portico ). Most likely it was either a temple or some other public building. Not far from there, Charles Bonnet uncovered part of a thermal bath with hypocaust heating in 1972 , which had been rebuilt after its destruction in the 3rd century. A pottery workshop could be seen at Les Pivoines - Crédit Mutuel - Rue de la 5ème Division Blindée. It was in operation between AD 120 and 160. In the immediate vicinity, on the site of the new town hall, there was a bronze foundry. In ancient times a paved path led past it. Further traces of streets and remains of buildings from the same period were found about a hundred meters further north, right next to the Protestant church. These two buildings - and probably the entire vicus as well - were probably destroyed by floods in the last quarter of the 2nd century.

From the third century, the finds in the vicus became increasingly rare. The heyday of the civilian settlement is likely to have finally come to an end from this time, also due to the increased number of barbarian attacks. However, the devastation caused by the barbarians cannot explain everything. It also appears that a marked change in the climate set in, which resulted in an increased incidence of flooding. The 3rd century was characterized by extreme poverty and a steady decline in the population living here. Only the buildings in the center were still inhabited. Only a few coins were found in the layers after 250, especially those of the Gallic usurpers Postumus and Tetricus I. It is not known whether the civil settlement was still inhabited in the 4th century.

economy

In addition to the geographical features, the fertile loess soils also favored agricultural use and thus the emergence of numerous other Gallo-Roman settlements in the vicinity of the fort. Above all, pastures, cereal and wine growing are proven. Wine growing probably became more important. In 1782 a bas-relief was discovered on which two winged genii with grapes were depicted on one side ; in 2008, ancient seeds and vines were recovered. Apart from agriculture, the ceramics and metal crafts were important for the regional economy. This required a large amount of firewood. This suggests the existence of large forests in the vicinity, which also provided timber. Clay, an important raw material for building houses and making ceramics, was also available in large quantities. River gravel was extracted on site. Stone material, including sandstone and limestone, was obtained from quarries in the Vosges. Because of its fine grain, it was preferred for sculptures and gravestones, and pink sandstone, which occurs around Voegtlinshoffen , was also widespread. Pure limestone was only found in rubble and roads.

The main part of the artisanal activity focused on the manufacture of ceramic ware. After a pottery workshop was discovered in 1967, numerous still intact ceramics were recovered. Some of them are on display in the Colmar-Unterlinden Museum. Notably, fragments of molds for the production of sigillata have also been found in the pottery. Probably an attempt was made here to produce their own terra sigillata . So far, however, no fragments have been found from these molds, which suggests that the manufacturing process has been stopped for some reason. The finds are also far too sparse to be able to judge the progress of these efforts today.

Another important handicraft branch was metal processing. Traces of workshops were found in three areas. The first place was near the pottery, in 1968 a workshop was found there with a furnace, leftover slag, individual bronze objects from the range of goods (brooches and a statuette of Mercury) and a melting pot. Several of these crucibles, slag remains and bronze fragments were also found at the New Town Hall. This workshop was probably also part of the business next to the pottery, as the distance between them is minimal. The third site in this regard was located in the east of the city, it was discovered in 1989 and re-examined in 2008.

Cult and religion

Several objects were discovered in Horbourg-Wihr that allow conclusions to be drawn about the cults of gods practiced here:

- A consecration altar with an inscription donated to Apollo-Grannus ;

- The fragment of a relief, on it the representation of Mercurius with a snake staff ( caduceus ) and the bronze statuette mentioned above;

- An altar to Victoria , the goddess of victory ;

- A stele depicting the fertility goddess Epona sitting on a horse with an apple in her hand;

- A relief that two winged genii - each of the left with the foot on a container filled with clusters of grapes in the hand and vat standing - shows;

- A consecration altar of Martius Birrius, dedicated to the Gallo-Roman pantheon of gods .

Burial grounds

All tombstones that were excavated in Horbourg-Wihr had been dragged from their original locations. One therefore had no clear idea of where exactly the burial grounds of the civil settlement or the fort were.

A total of twenty-four gravestones, almost all of them carved from pink sandstone, have been recovered so far. Many of them were built into the defensive wall as building material ( spoil ) during the construction of the late antique fort . Others had been reused for sarcophagi in the Merovingian era. Determining the location of the cemeteries is also made difficult by the redesign of the topography due to the frequent floods that have struck Horbourg-Wihr since ancient times. Large parts of the area of the ancient settlement and the fort are covered by a thick layer of mud. According to the Roman tradition, the burial grounds must have been outside the urban area. Since they were always laid out along the arterial roads, there are only three possible locations:

- Near the road to Kreuzfeld-West, where a 4th century grave and headstone were discovered

- next to a road to Biesheim two tombstones and several cremations were found,

- A little further south of it, an ancient grave was found in 1894 and a gravestone nearby.

Other graves were marked on an excavation map by Pastor Herrenschneider, but not described in detail by him.

Monument protection

The facilities are ground monuments within the meaning of the French Monument Protection Act ( Code du patrimoine ). Archaeological sites - objects, buildings, areas - are defined as cultural treasures ( monument historique ). Robbery excavations must be reported immediately. Probing in protected areas and unannounced excavations are prohibited. Attempts to illegally export archaeological finds from France will result in at least two years imprisonment and 450,000 euros, willful destruction and damage to monuments will result in up to three years imprisonment and a fine of up to 45,000 euros. Archeological finds made by chance are to be handed in immediately to the responsible authorities.

See also

List of forts in the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes

literature

- Emile Alphonse Herrenschneider: Römercastell and Grafenschloss Horburg; with highlights on Roman and Alsatian history. With plans and drawings by building councilor Winkler. Barth, Colmar 1894.

- Societe pour la conversation des monuments historiques d 'Alsac: Cahiers Alsaciens D' Archeologie D'Art et D 'Histoire, Puplies avec le consours du Center des National dela recherche Scientifique, No. VIII. Strasbourg 1964, pp. 80-84.

- Mathieu Fuchs, Charles Bonnet: Horbourg-Wihr à la lumière de l'archéologie, histoire et nouveautés: mélanges offerts à Charles Bonnet. Festschrift. Association ARCHIHW, 1996, ISBN 2-9507051-2-X .

- Jürgen Oldenstein: Alzey Castle. Archaeological investigations in the late Roman camp and studies on border defense in the Mainz ducat. Habilitation thesis. University of Mainz, 1992, pp. 312-317. (PDF, 14.9 MB)

Web links

- Roman statues from Horbourg in the Colmar Museum

- Website Association d'Archéologie et d'Histoire de Horbourg Wihr (ARCHIHW)

Remarks

- ↑ Marcus Zagermann: The Breisacher Münsterberg. The fortification of the mountain in late Roman times. In: Heiko Steuer, Volker Bierbrauer (Ed.): Hill settlements between antiquity and the Middle Ages from the Ardennes to the Adriatic. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-020235-9 , pp. 165-185.

- ↑ Memoire sur Argentovaria, Ville des Sequaniens.

- ↑ Jürgen Oldenstein: 1992, p. 315.