Corinium Dobunnorum

Corinium Dobunnorum (or just Corinium ) is the ancient name of the Roman city of Cirencester in Gloucestershire , England . With 96 hectares it was the second largest city in Roman Britain . The city was the capital of the Dobunni Civitates and thus the administrative center of a tribal community. As a suburb of this municipality, the city was equipped with all important public buildings such as a forum , a basilica , baths and an amphitheater . The city was also the administrative and economic center in the west of the British Isles. At the end of the 3rd century AD, Corinium Dobunnorum became the seat of the administration of the newly established Roman province of Britannia prima .

Surname

Corinium is the Romanized version of a Celtic name that may have originally been Cironion . Other interpretations draw a connection to Ceri in Wales or to the Celtic mythical term Cuirenn . Accordingly, the city appears as Cironium Dobunorum with the geographer of Ravenna . Dobunni is the name of the Celtic tribe who settled here and minted their own coins even before the arrival of the Romans. Overall, the city is mentioned in ancient sources by only two geographers. It does not appear in any other sources. Claudius Ptolemy (II, 3, 12) describes Corinium (κορίνιον) as the chief town of the Dobunni . It is not known when the city received this name. Perhaps it was the name of the nearby oppidum and was later transferred to this settlement, or the military camp got the name when it was founded.

Location and surrounding area

Corinium Dobunnorum is located in the west of what is now England in a region which is very productive in agriculture and which makes the region one of the most prosperous in England to this day. The town sits on the small river Churn at the point where it enters the flat alluvial land of the Thames from the limestone mountains of the Cotswold . The walled urban area lies almost exactly in the valley created by the river. The city is located at the junction of important roads, which certainly quickly contributed to its growth and importance. From the southwest the " Fosse Way " met the city, which connected the Isca Dumnoniorum ( Exeter ) , which is close to the sea, with the Roman colony of Lindum Colonia ( Lincoln ). " Ermin Street " came from the southeast and connected Calleva Atrebatum ( Silchester ) with the Roman colony of Glevum ( Gloucester ) north of the city. The " Akeman Street " had its starting point in the city and connected it with Verulamium ( St Albans ) further east in the province of Britannia .

The area surrounding Corinium Dobunnorum is extremely rich in Roman villas ( villae rusticae ) , most of which had their heyday in the 4th century AD, when the city became the capital (caput provinciae) of the newly created province of Britannia prima . Approximately 25 villas are within a 20 kilometer radius. These include the mansions of Woodchester and Chedworth , which also stand out for their rich furnishings. These villas are often founded in the 1st or 2nd century AD, but were only expanded and richly furnished at the end of the 3rd and beginning of the 4th century AD. This is certainly connected with the elevation of Corinium Dobunnorum to the provincial capital, but can also be observed in other places and also has to do with social changes in late antiquity . The cities lost their importance. The country estates gained in importance.

The next major Roman city was Glevum , just 27 kilometers northwest of Corinium Dobunnorum. This proximity of two important cities is unique in Roman Britain. Glevum had the status of a colonia , a Roman colony. It was a prosperous city from the start, but it never showed significant growth, while Corinium Dobunnorum quickly became Britain's second metropolis. One can only speculate about the reasons for these different developments. It has been suggested that the citizens of Glevum , who were mostly war veterans, were simply more conservative and not open to newcomers, which discouraged them from moving to the colony and therefore preferred Corinium Dobunnorum, where veterans did not dominate the interests of the city.

history

The city or at least one of its predecessors in this area (probably 4.8 kilometers to the northwest, near Bagendon ) was the capital of the Celtic tribe of the Dobunni in pre-Roman times . The Dobunni and with them this part of Britain came under Roman rule in AD 44 to 45. In AD 47, the border was set at the location of the later "Fosse Way" and various border camps were set up to secure the newly conquered province. A military camp was also built on the site of the later Corinium Dobunnorum , next to which a civilian settlement ( vicus ) was built. This camp was replaced by another around 50 AD. According to the testimony of two gravestones, a cavalry division was stationed here. It was the Ala Gallorum Indiana and later the Ala I Thracum .

The old Celtic city of Bagendon was apparently not destroyed, but it seems that more and more people moved near the military camp as the riders stationed there were financially strong and the locals could hope for lucrative business opportunities. This civil settlement next to the camp consisted mainly of wooden buildings. The actual camp was rectangular with trenches and was located in the center of the later city. In the following years the provincial border shifted, which meant that the camp was no longer needed and the troops were withdrawn. When the camp was abandoned, there was already a flourishing civil settlement here. The Roman city of Corinium Dobunnorum was founded in the mid-1970s and assumed the function of the administrative center of the Civitates of the Dobunni. The reasons for choosing this location seem clear. On the one hand, the place had a favorable location in terms of traffic, on the other hand, probably numerous Dobunni lived here, including probably many who belonged to the ancient nobility of the Celtic tribe and probably still held influential positions.

The newly founded city received a city map with streets intersecting at right angles and public buildings, including a market, a forum and a city wall (this was not built until the end of the 2nd century AD). In the following 3rd century AD, Corinium Dobunnorum experienced its first heyday, which can be seen above all in the richly furnished residential buildings in the city area. The forum was one of the largest in Roman Britain, which in turn underscores the city's economic importance from the start.

In 212 or 213, Caracalla divided the Roman province of Britannia into the provinces of Britannia inferior (northern England up to Hadrian's Wall ) and Britannia superior (southern England and Wales). Corinium Dobunnorum now probably belonged to the province of Britannia superior , the capital of which was Londinium ( London ). The third century was a time of political crisis and economic decline in almost all parts of the Roman Empire. It was probably during this period that the city received a stone wall. There is hardly any evidence of construction work on other public buildings.

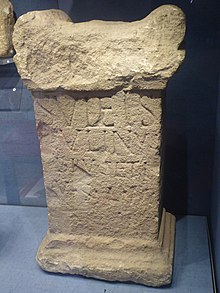

Under Emperor Diocletian there was a further division of Roman provinces. The city probably became the capital of the province of Britannia prima in the 4th century AD . This is nowhere explicitly mentioned, but in 1891 the base of a column was found which was built by L. Septimius […], the governor ( praeses ) of the province of Britannia . In addition, the numerous renovations in the 4th century indicate a special position of the city. During this time, the city experienced its greatest heyday, which can also be seen in the numerous houses richly decorated with mosaics . The structure of the residential development in the city changed. Many small and medium-sized residential buildings were torn down and replaced by a few, often magnificent, city villas. This may indicate a change in the social structures in the city and has probably to do with the disappearance of the middle class. The surrounding area also experienced a period of particular prosperity in the 4th century. No other part of Britain is home to so many large and richly furnished villas.

Little is known about Christians in the city. In 1868 the following letters were found scratched on a fragment of plastering. However, as far as we know today, it is a magical sator square :

- ROTAS

- OPERA

- TENET

- AREPO

- SATOR

The string rearranged to a cross results in the Our Father PATERNOSTER. The inscription is interpreted as a secret reference to Christianity at a time when this religion was still suppressed.

Decline of the city

The city's heyday lasted until around 375. After that there was a slow decline. It was estimated that around 375 23 of the excavated townhouses (which of course only represented a small part of the former development) were still inhabited. However, by 400 there were only ten, by 425 only four and after that not a single one. A comparable study examined the number of occupied or at least used rooms. Accordingly, the city experienced its greatest heyday around 350 with around 150 rooms that were used in the excavated areas. At 375 there were still around 145 rooms. In contrast, around the year 400 it was only around 45 and around the year 425 less than 10. After 375, a sharp decline can be observed. Corinium Dobunnorum, like almost all Roman places in Britain in the 5th century, was slowly abandoned. The forum may have been used until around AD 430. Archaeological remains from this period and the following are, however, extremely sparse. The remains of simple huts were found in the amphitheater, indicating that a remaining population withdrew to this easily defendable place in the following years. In the year 577, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle mentions a British king in the city and that the city was conquered by the Saxons Cuthwine and Ceawlin . There the city is already referred to as the Cirenceaster .

Research history

Research into the Roman remains in the city began very early. John Leland (1503–1552) was appointed King's Antiquary by Henry VIII in 1533 , and he traveled to Britain to describe ancient monuments. At Cirencester he described the city walls as nearly two miles long. He copied an inscription with the text PONT MAX and collected coins. He saw mosaics and described the amphitheater without recognizing it as such. Another early researcher was William Stukeley (1687–1765). In 1724 he published the book Itinerarium Curiosum , in which he treated various ancient monuments of England. He described the ancient city walls of Cirencester and mentions that mosaics and coins would be found in the city almost every day. Samuel Rudder (1726-1801) wrote a work on the history of Gloucestershire (1779). Part of it was published as a separate book as The History and Antiquities of Cirencester . Many archaeological finds were described in it. Rudder was probably the first to recognize the function of the remains of the amphitheater. Samuel Lysons (1763-1819) published the first map of Cirencester in 1817 with the outlines of the ancient city. The first archaeological excavations at Cirencester may have taken place as early as 1824. John Skinner (1772–1839) visited the city on his extensive travels. His notes indicate that he was digging the amphitheater to see if it had stone benches. He concluded that the theater was not Roman but British and was built under Roman instructions. In the nineteenth century, the main interest was in collecting objects. Extensive collections were created, especially in private hands, which then formed the basis for museums. In Cirencester, the discovery of the mosaics on Dyer Street in 1849 led to the establishment of a museum. Lord Bathurst had these mosaics lifted at his own expense. In 1856 a museum was set up to display the mosaics. To locate the city's basilica, Wilfred Cripps carried out excavations from 1897 to 1898. He left behind good plans, but he hardly provides details on the building history, which was otherwise common in archeology at the time. At the beginning of the 20th century there was a first scientific study of the city. Francis John Haverfield collected all the data on the city and published it in an article. Since 1952, Mary Rennie directed various excavations in the city. She had dug at Verulamium and Maiden Castle with the well-known British archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler and was therefore familiar with excavations of Roman cities. In 1958, the Cirencester Excavation Committee was established to specifically take care of excavations in the city. In the 1960s and 1970s in particular, there was a great deal of construction work in the city that made it possible to carry out at least partial excavations. The city was systematically examined and the excavation results were published in several volumes, which not only presented the current excavations, but also older ones.

The town

The city had 30 insulae (city blocks), which modern research numbered with Roman numerals. In many places, remains of the ancient city have been found during excavations, so that the place is one of the better explored Roman cities in England. Nevertheless, many questions remain unanswered. Above all, there are various public buildings that are well documented for almost all Roman cities of this size, but not so far in Corinium Dobunnorum. So far, no temple or public bath could be identified with certainty.

Nothing is known about the number of inhabitants. All considerations remain very rough estimates that are often based on medieval cities of comparable size. Accordingly, Corinium Dobunnorum may have had between 5,000 and 20,000 inhabitants.

Forum

The city's forum is only known to a small extent. Various digs provided a general picture of the building, although many detailed questions remained unanswered. The system (168 × 104 meters) was located in the center of the city and took up an entire insula ("Insula I"). In the center was the usual large courtyard, which was lined with shops. To the south there was a large basilica with an apse . In the 4th century AD the forum was divided into two parts by a wall in the courtyard. The corridor behind the colonnades in the courtyard was provided with a mosaic floor decorated with geometric patterns. The mosaics date from a coin after 335 AD. These changes may be related to the elevation of Corinium Dobunnorum to the provincial capital. These late changes are also noteworthy because forums were abandoned in many other Roman cities in Britain at about the same time.

The basilica was partially excavated between 1897 and 1898 and then again in 1961. She had three ships and was about 101 meters long and 23.8 meters wide. There was an apse on the west side, while there was none on the east side. The floor of the apse was paved with stones in the first construction phase. On the south outside of the basilica there was a series of rooms that flanked the long side of the basilica. It was probably initially business rooms, but they were converted into workshops in the 4th century AD. Evidence of metal processing was found here. The main entrance to the apse was probably to the north. In the apse there was a fragment of an eye from a larger than life bronze statue.

The actual forum was surrounded by a colonnade on the outer facade. The 107 × 84 meter courtyard also had a colonnade. The courtyard was paved with stone slabs. The forum and basilica were built in the last quarter of the 1st century AD. Corinthian capitals , which have been found nearby, may have come from here . Marble fragments indicate rich furnishings. The basilica was renovated as early as the middle of the 2nd century AD. It was probably built too quickly, without considering that under it were the remains of the trenches of the Roman military camp, which in turn did not offer enough support over time. As a result, parts of the walls sank and had to be renewed. Further renovations date back to the 4th century AD, although it is not always clear whether the changes were a single renovation or whether these modifications took place over time, if necessary.

market

In addition to the forum, the city may also have had a separate market. This was apparently almost as big as the forum and thus took up at least half of the "Insula II", which was right next to the forum. The system here was initially a free space. This was limited to a number of shops in the 2nd century AD. There were porticoes on the street side, but also built towards the courtyard. According to the coin finds, the building was abandoned around 350 to 360 AD. The interpretation as a market ( Macellum ) is far from certain. Another option is that it was a palaestra for a public bath. Pits with animal bones dating from the 2nd to the early 5th centuries AD have been found near the building. This was taken as sure evidence that this was a market, perhaps even a meat market. However, since these pits cover such a long period of time and partly date to a time after the construction was abandoned, the connection of the pits to a market does not seem very likely. After all, the separation of market and forum is remarkable and suggests that Corinium Dobunnorum benefited from the wealth of an agriculturally prosperous area from the very beginning.

amphitheater

The city had an amphitheater about 500 meters southwest of the city center, outside the city walls. The theater is located in the hollow of a quarry and was probably built at the turn of the 1st to the 2nd century AD. The entrances to the 41 × 49 meter arena were clad with wood and dry stone walls. The spectator stands were on the slopes of the hollow. A short time later, at the beginning of the 2nd century AD, the arena and the access to the arena in the north were clad with stone. In the middle of the 2nd century AD the entrance was renovated again. Two small chambers were added on either side of the entrance. The walls that separated the arena from the stands were completely rebuilt. It is not certain how long the amphitheater was used as such. At least in the middle of the 4th century AD, the theater as such was abandoned and used for other purposes. During this time, the walls of the arena in particular were torn down and its access was expanded. There were numerous post holes in the arena . It has been suggested that it was now being used as a market. In the 5th century AD it appears to have been a haven for the rest of the city's population. The theater is still preserved today as a large, grass-covered hollow. In the Middle Ages and modern times, the ruins were known as the Bull Ring .

More buildings

In "Insula VI" remains of another public building came to light. It measured about 75 by 38 meters. Walls were found that can be expanded to form a large courtyard with access. The halls were decorated with simple mosaics. The outside of the complex had a portico. The interior formed a large courtyard, but only a small part of it could be excavated, so it is not known whether there were other structures inside the courtyard. The facility was built in the middle of the 2nd century AD and operated until the early 5th century AD. The function of this district is unknown. It may have been a market, a temple precinct, or perhaps the palaestra of a bath, although the latter option seems the least likely.

It has not yet been possible to locate other public buildings with certainty. In “Insula XXX”, during various very limited excavations between 1962 and 1968, walls that probably formed two semicircles came to light. Maybe it's the remains of a theater. However, the excavation sections are far too limited to allow certain statements. There are also inconsistencies. The few theaters in British cities are mostly in the city center, while these walls are on the outskirts. One option, after all, is that the theater was connected to a temple precinct. This may also be the case here, although nothing of the temple has yet been found.

Temples in Corinium Dobunnorum are only documented by inscriptions. So there seems to have been a sanctuary for the Deae Matres . This is evidenced by the discovery of sculptures and altars in "Insula XX", which are connected to this goddess. However, it has also been suggested that these finds can be identified with a sculpture workshop.

In "Insula XIII" one found a large open area laid out with stones. It has been suggested that it is the forecourt of a temple. However, this cannot be further proven without further excavations. A Corinthian capital (about one meter high) also comes from Corinium Dobunnorum, adorned on each side with the figure of a deity whose upper body protrudes from the capital. The capital may come from a giant column of Jupiter , from which part of the inscription on the base has been preserved. The figures depicted are possibly Celtic deities. The quality of the sculpture is high and it has even been suggested that a Gallic artist was at work.

Two inscriptions and a consecration stone for the genii cucullati , Gaulish-Roman hooded demons, were found in the city, who were also venerated here.

city wall

The construction date of the city wall is uncertain and controversial. An earth wall was probably built in the middle of the 2nd century AD, which was about 14 meters wide, enclosed the entire city and was about 3.6 kilometers long. The exact structure of this first attachment is uncertain. There was probably a wooden palisade, wooden towers and stone city gates. In the middle of the 3rd century AD a stone wall was placed in front of the earth wall. In a third phase in the 4th century AD, the stone wall was reinforced to three meters thick and the still standing earth walls were further increased. The towers were then abandoned and replaced with new ones on the outside of the wall. The city wall had at least four, if not more, gates. Two gates could at least partially be excavated. These are the modern so-called Bath Gate and Verulamium Gate , both of which are on the "Fosse Way", which enters the city in the southwest and leaves it in the northeast. The Verulamium Gate is almost 30 long and has a semicircular tower on each end. The gate once probably had four passages. The Bath Gate is a bit smaller but similar and was only about 22 meters long. It probably once had two passages. The Verulamium gate was thus once more monumental. It was the main gateway to the city for traffic coming from the Londinium , the largest city in Britain. It was from there that most of the travelers and traders probably came, who then only had Bath Gate behind them when they continued their journey .

Water supply

As a large city, Corinium Dobunnorum must have had a regular water supply, especially in order to supply the baths and other public as well as private buildings with clean water. The clearest remains of a water pipe were found at the Verulamium Gate in the west of the city. During the excavations, the remains of a wooden water pipe, the parts of which were connected with iron clips, came to light here. The line dates to the 4th century, but may have replaced an older line. The excavator suspected that one of the towers in the city gate served as a water container (catstellum aquae) . It is not known where the water in the tap came from. The churn flows right next to the gate. Cleaner water may have come from a more distant source, but it has not yet been identified with certainty. It can be assumed that this was not the only water supply, but so far nothing more concrete has been found in excavations. There were also various fountains within the city. The remains of a pump were found in one of them.

Residential development

Residential buildings have been recorded during excavations throughout the city. Often, however, it was only possible to excavate individual room groups, so that in many cases the character of individual residential buildings remains uncertain. The first residential buildings were made of wood. Most of them were strip houses ; they are residential buildings that are very narrow and reach deep into the insula along the side of the street. In the front part there were mostly shops or workshops, in the rear part the actual living area. It is likely to have been primarily the residential buildings of the urban middle classes, i.e. above all residential buildings of the craftsmen and traders. The earliest stone houses were built at the beginning of the 2nd century AD. This is earlier than many other Roman cities in Britain, perhaps simply because stone was easy to obtain around the city. In the city there was also numerous evidence of larger houses, which usually consisted of two or more wings that were grouped around a courtyard. Some of them had porticos. Many houses received first-class mosaics as early as the 2nd century. These are obviously the houses of the urban upper class. The urban development does not seem to have been very dense. In some of the insulae the houses stood close together. But in "Insula VI", close to the city center, there was even a few meters distance between the strip houses. In this insula a large area lay fallow for about a hundred years in the 3rd century.

Insula III

In 1837 a mosaic from the 4th century AD was found inside the "Insula III". It has a pattern of two intertwined squares that were once depicted four times. In the center of them there was a stylized flower, which has only been preserved in one case.

Insula IV

In the "Insula IV", the remains of several residential buildings came to light during construction work in 1958. A large house once had at least two wings. The wing on the west side had a portico to the courtyard, which was decorated with a simple mosaic. Another 7.8 x 8.1 meter room was also decorated with a geometric mosaic dating to the 2nd century AD.

Insula V

During excavations in 1961, in the far north of the "Insula V", a number of shops came to light that were initially made of wood, but were replaced by stone structures over time. A number of stoves were found, although it is unclear whether they were domestic stoves or those for a craft. In 1972, further excavations in the same insula uncovered similar structures. Some stone work is remarkable. There were three altars, two column bases, a headless eagle and a group of Genii Cucullati . Wall paintings from the late 1st century AD also come from here, some of which have been reconstructed. They show red panels over a base that imitates marble . The fields in between are black.

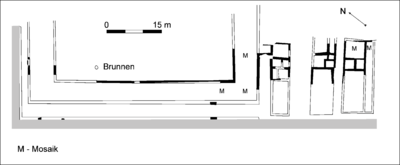

Insula VI

In "Insula VI" there was a public building from which the courtyard was exposed. Strip houses stood next to them. In other parts of the insula remains of at least four large townhouses have been excavated. The largest was partially exposed in 1974. In its place were again strip houses until the end of the 3rd century AD, which were replaced by a large stone building that was inhabited at least until the end of the 4th century AD. At least four rooms of a strip house could be recorded during the excavations. The later house had a portico to an inner courtyard and was decorated with mosaics. The largest of them was decorated with a mosaic, the remains of which show a kantharos and two dolphins, but otherwise decorated with geometric patterns. There is also a mosaic from the great house of the 4th century AD.

Insula VII

The remains of a house were found here, furnished with hypocausts and perhaps with mosaics. There were collections of loose mosaic stones.

Insula IX

Remains of various buildings came to light within the "Insula IX" over time. In this insula, the remains of an octagonal building were excavated in 1929 and 1958, the floor of which was partly decorated with a mosaic. The building consisted of an octagonal interior with a walkway. Most of the rooms had hypocausts. The building may have been part of a bathroom. Remains of a mosaic that probably belonged to a residential building come from the same insula. Only parts of the plan of another building have survived. The house consisted of at least three larger and several smaller rooms. From another house there were mainly two adjacent rooms with apses, both of which were equipped with hypocausts. They are each about four meters long and three meters wide. They may have belonged to a private bath. Various rooms in the house had wall paintings.

Insula X

In the area of the "Insula X" in 1922, during construction work, the remains of four rooms came to light, all of which were decorated with mosaics. A large room was found, to the north of which there were two smaller ones and to the west of this group of rooms there was probably a portico. The mosaics were filled in again and are known today from color drawings and photographs. They date to the end of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. They all show geometric motifs.

Insula XII

In the east of the city, two town villas from the 4th century AD were completely excavated. "House 1", located in the north, was initially a simple rectangular building that was expanded over time and expanded again and again. The house had a porch to the south, which served as an entrance and was decorated with a simple, monochrome mosaic. From there you came into a long room that divided the house in half. This room was also decorated with a monochrome mosaic. On the west side there was a bathing wing and on the east side there was the living area. Two rooms in the living area had more elaborate mosaics, while otherwise all rooms were again laid out with single-colored or simple two-tone floors. The decorated mosaics date to the 4th century AD. The larger one shows geometric patterns and two interlocking squares in the center. A hare can be found in the center as a motif. The room with the mosaic received heating in the 4th century AD, with the walls for the hypocausts being built on top of the mosaic. This may have helped make it so well preserved. In the bathing wing there was a well-preserved mosaic showing a meandering pattern across the entire area . When lifting the mosaic, auxiliary lines could be observed in the screed below, which were obviously drawn before the mosaic was laid. A children's burial was found under a pile of stones just north of the house. The child, who died during or shortly after birth, had a vessel with a stone as a lid as a burial gift. Various rooms in the house had wall paintings.

The southern house ("House 2") had a portico on the north side and was richly decorated with mosaics, which, however, are not well preserved. The mosaic in the portico shows a labyrinth and several meanders. Other mosaics in the house are more complex with different patterns. This house also had heated rooms. Two simple buildings belong to this house, which in one case consisted of only one large room, in the other case of one large and three smaller rooms. They were probably farm buildings, which led to the assumption that the whole complex was a villa rustica within the walls of a city.

Insula XVII

Mosaics from a house in "Insula XVII" date from the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD and are among the finest Roman in Britain. Little is known of the house in which they were laid out. As early as 1783, when a cellar was being built, large parts of a mosaic showing a sea scene were found. There are fish, crabs, but also fantastic marine animals. In the center there was perhaps the image of Neptune , but it was not preserved. Today the mosaic is only known from an old drawing. In 1849 another, smaller but better preserved mosaic came to light. The mosaic consists of a round image field in the middle and around it eight semicircles with partly figurative, but also purely ornamental patterns. Hunting dogs are shown in the central field of view. The image section in which the hunted animal was depicted is lost. Other picture fields show sea animals and the heads of Neptune and Medusa . Another figural mosaic with the four seasons as busts and mythological figures comes from a neighboring room in the same house. It was found in 1849. The mosaic is roughly square with a side length of eight meters. It is framed on three sides by a meander. This framing is lost on the fourth page. The main field shows nine circles with motifs. In the circles at the corners there are busts of the four seasons. Spring, summer and winter are still preserved today. In the other fields there are mythological scenes, of which only two have survived. Once, Silenus is depicted on a donkey. In the second space that has been preserved, Aktaion is shown being attacked by dogs. Four small square fields that lie between the larger ones also show pictures. One time the head of Medusa has been preserved, another time the figure of a bacchant . Extensive remains of wall paintings were also found in the house.

Insula XVIII

Geometric mosaics and remnants of high-quality wall paintings come from a house in "Insula XVIII". Some rooms had hypocausts.

Insula XX

In the "Insula XX" the remains of several residential buildings were excavated. In a house that was partially excavated in 1905, parts of a bathroom and a mosaic with the bust of Oceanus were found . In 1964 three rooms were found from another house, all of which were furnished with geometric mosaics. The mosaics may date from the turn of the 2nd to the 3rd century AD. A mosaic found in 1909 may come from a third house and dates to the 2nd century AD.

Insula XXI

In 1950 the remains of a well-preserved mosaic from the 2nd century AD came to light in the "Insula XXI".

Insula XXIII

During excavations in 1962, small parts of a house were recorded. There were three construction phases in the course of which the house was changed. The first building dates to the end of the 1st or 2nd century AD. Conversions then took place in the 2nd century AD. A wall from the first phase was almost 1.8 meters high. Extensive remains of wall paintings were still adhering to the wall. Above a black plinth, which is decorated with geometric patterns, is the main part of the wall with wide yellow fields between narrow green fields.

Insula XXV

In "Insula XXV" between 1964 and 1966, the remains of a large house with an inner courtyard came to light. The courtyard had a gallery, which in turn was probably decorated with six columns. The courtyard walls were decorated with murals. Coins are largely dated to the 4th century AD, but there is little evidence of when the house was built. In a few places there is evidence of older buildings in place of this house.

Others

Houses outside the city walls could also be observed, which in at least one case were decorated with mosaics. At Barton Farm , about 500 meters north of the city walls, a large mosaic was found in 1824, which shows Orpheus as the central motif in an inner circle . Various animals are shown in two further outer circles. Another house was excavated near the amphitheater, directly on “Fosse Way”. It had two rooms. It was probably a workshop with living space. In the first and larger room there was a furnace that perhaps served as a forge. The building was constructed around 280 and was in operation until around 330 AD. At the end of the fourth century the area was used as a cemetery.

Trade and commerce

As the capital of a civitates, Corinium Dobunnorum was the economic center of the Dobunni tribe, as the great forum and the market testify. The trade took place on different levels. At the local level, agricultural products from the area were traded in the city and possibly resold. In return, the city delivered handicraft products to the area. In addition to this local trade, products from other provinces were also imported into the city and traded from here to the surrounding area. This can be clearly seen in the ceramic. In the middle of the 1st century AD, when the military camp stood here, most of the pottery came from workshops in Gaul . At the end of the 1st century this changed drastically. Most of the ceramic vessels found in the city from this period were made in Britain. It is mostly a matter of simple utility ceramics. Only high quality Terra Sigillata came from Gaul, but it still represented a significant proportion of the ceramics in circulation in the city. Most of the pottery from this period came from workshops in Wiltshire , south of Corinium Dobunnorum. In the 4th century these potters lost their importance and most of the pottery used in the city came from Oxfordshire potteries .

In Corinium Dobunnorum numerous mosaics were found, the quality of which is higher than the British average and which attests to the prosperity of the city and the region. Here also operated a mosaic workshop, engaged in the research than the Corinische School (Corinian School) is called. It was the largest workshop of its kind in Britain, laying numerous floors in the city and surrounding villas in the first half of the 4th century AD. It could be identified using various small details and motifs on various mosaic floors. However, the exact organization of this workshop has not been clarified and there have been attempts in recent years to subdivide the Corinian School into other groups, such as the Orpheus Group .

Many sculptures come from Corinium Dobunnorum , the quality of which is higher than that of the British province. These works include the above-mentioned capital, a giant Jupiter column, the head of a Mercury statue, the head of a river god and a relief with three mother goddesses. Typical for these works are a combination of classical naturalism with a native expressiveness and a strong individuality. It has therefore been assumed that a Gallic workshop or at least a Gallic artist settled here. However, this cannot be proven and a British artist may well have made high quality works. After all, even the name of a sculptor is known: Sulinus , son of Brucetus left altars in Aquae Sulis ( Bath ) and Corinium Dobunnorum that were dedicated to the Suleviae .

Another branch of industry that can be developed in the city is a goldsmith, as a crucible in which there were still gold remains was excavated in "Insula II". There may also be a glass-making workshop here. In the city, or at least in the surrounding area, there was also a brickworks that stamped its bricks with the words TPF .

graveyards

There were various cemeteries outside the city. These could be found mainly in the west and south. Particularly in the southwest near the amphitheater, a continuous part of the cemetery with 405 burials was excavated. These date to the 4th and maybe even the 5th century AD. Since the dead were rarely given additions at this time, it is often not easy to date them precisely in individual cases. Some of the buried were buried in wooden coffins. There were nails and sometimes also hinges. There were some stone sarcophagi that were undecorated and rather roughly hewn. In one case a lead coffin was found in a sarcophagus.

The corpses were examined very carefully and provide a good cross-section of the population at the time. It is the largest investigated cemetery in Western Europe from this period. A particularly large number of men were buried (the ratio of men to women was 2 to 1), with an average age of 40.8 and that of women 37.8. The men were on average 1.70 meters tall, the women 1.52 meters tall. Diseases could often be detected, such as the oldest documented cases of gout in the Roman Empire . A good 80 percent of those buried here suffered from arthritis . The high proportion of lead in the bones was also remarkable . Six of the people buried here had apparently been beheaded. The condition of the teeth was generally very good.

Sarcophagi and inscribed gravestones were found in other cemeteries around the city . From these inscriptions, it is known that a certain Nemomnus Verecundus died at the age of 75 and that Pulia Vicana and Publiius Vitalis had Roman citizenship. Philus was a Sequan and died in Corinium Dobunnorum at the age of 45. Casta Castrensis and Julia Casta died at the age of 33, Aurelius Igennus (Ingennus) at the young age of six and Lucius Petronius Comitinus at the age of 40. Another tombstone names a certain Saturninus and another with a badly damaged inscription may belong to a legionnaire of Legio XII Fulminata , which was stationed in Melitene on the Eastern Front. Overall, the gravestones show that some of the city's residents came from different parts of the Roman Empire.

Roman remains in today's city

Not many remains of the ancient city have survived in what is now Cirencester. The amphitheater forms a large hollow in a park. In the west of the city, parts of the city wall with the towers can be seen. In the southeast of the ancient city they have been preserved as earth walls. In the city center, the apse of the basilica is marked on the road surface by different colored stones in a dead end street. The finds in the urban area can be viewed in the Corinium Museum in Cirencester. The collection is one of the most important Provincial Roman museums in England and is particularly famous for the numerous mosaics on display.

Remarks

- ^ Group 9: Worcestershire, Gloucestershire and northern Hampshire

- ^ Albert Lionel Frederick Rivet, Colin Smith: The Place Names of Roman Britain. London 1979, ISBN 0-7134-2077-4 , p. 326.

- ^ Roger White: Britannia Prima, Britain's Last Roman Province . Chalford 2007, ISBN 978-0-7524-1967-1 , pp. 123-147.

- ↑ Wacher: The Towns of Roman Britain , pp. 164-165.

- ↑ Wacher: The Towns of Roman Britain , pp. 28-29.

- ^ Wacher: The Towns of Roman Britain , p. 320.

- ^ Neil Faulkner: Urban Stratigraphy and Roman History . In: Neil Holbrook (ed.): Cirencester, The Roman Town Defences, Public Buildings and Shop , pp. 371-388.

- ^ Francis Haverfield: Roman Cirencester , in: Archaeologia 69 (1920), pp. 161-209.

- ^ Alan D. McWhirr: The Development of Urban Archeology in Cirencester and further afield . In: Neil Holbrook (Ed.): Cirencester, The Roman Town Defences, Public Buildings and Shops , pp. 1-5.

- ^ Sheppard Frere: Britannia, a history of Roman Britain , London 1967, p. 262.

- ↑ Neil Holbrook, Jane Timby: The basilican and Forum . In: Neil Holbrook (Ed.): Cirencester, The Roman Town Defences, Public Buildings and Shops , pp. 99-121.

- ^ Neil Holbrook: The Shops in Insula II (The possible Macellum), Excavations directed by JS Wacher 1961 . In: Neil Holbrock (ed.): Cirencester, The Roman Town Defences, Public Buildings and Shop , pp. 177-188.

- ^ Neil Holbrook, Alan Thomas: The Amphitheater, Excavations directed by JS Wacher 1962-3 and AD McWhirr 1966 . In: Neil Holbrook (ed.): Cirencester, The Roman Town Defences, Public Buildings and Shop , pp. 145-175.

- ↑ Jane Timby, Timothy C. Darvill, Neil Holbrook: The Public Building in Insula VI, Excavations directed by JS Wacher 1961, AD McWhirr 1974-6 and TC Darvill 1980 . In: Neil Holbrook (Ed.): Cirencester, The Roman Town Defences, Public Buildings and Shop , pp. 122-141.

- ^ Neil Holbrook, Alan Thomas: The Theater, Excavations directed by JS Wacher 1962 and AD McWhirr 1966-8 . In: Neil Holbrook (Ed.): Cirencester, The Roman Town Defences, Public Buildings and Shop , pp. 142-145.

- ↑ Jocelyn Toynbee : Art in Roman Britain , London 1961, p. 165, No. 95, plates 97-100.

- ↑ Cosh, Neal: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume IV, Western Britain , pp. 75-76.

- ^ Cosh, Neal: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume IV, Western Britain , pp. 76-79.

- ^ Alan D. McWhirr: Houses in Roman Cirencester. P. 247.

- ^ Norman Darvey, Roger Ling: Wall painting in Roman Britain. Alan Sutton, Gloucester 1982, ISBN 0-904387-96-8 , p. 97.

- ^ D. Mary Rennie: Excavations in the Parsonage Field, Cirencester , in: Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society , 90 (1971), pp. 64-94 PDF

- ^ Cosh, Neal: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume IV, Western Britain , pp. 79-82.

- ^ Cosh, Neal: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume IV, Western Britain , p. 82.

- ^ Cosh, Neal: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume IV, Western Britain. Pp. 83-84.

- ^ Alan D. McWhirr: Houses in Roman Cirencester. P. 193.

- ↑ Linda Viner, in: Alan D. McWhirr: Houses in Roman Cirencester , pp. 200–201.

- ^ Cosh, Neal: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume IV, Western Britain , pp. 84-88.

- ^ Alan D. McWhirr: Houses in Roman Cirencester , pp. 23-45, 131.

- ↑ Linda Viner, in: Alan D. McWhirr: Houses in Roman Cirencester , p. 122.

- ↑ Reconstruction drawing of the villas (fig. 2) ( Memento of the original dated June 9, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Cosh, Neal: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume IV, Western Britain. Pp. 107-110.

- ^ Cosh, Neal: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume IV, Western Britain. Pp. 105-113.

- ^ Cosh, Neal: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume IV, Western Britain , p. 115.

- ^ Cosh, Neal: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume IV, Western Britain , pp. 115-122.

- ^ Cosh, Neal: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume IV, Western Britain , pp. 122-123.

- ^ Alan D. McWhirr: Houses in Roman Cirencester , p. 255.

- ^ Norman Darvey, Roger Ling: Wall painting in Roman Britain. Alan Sutton, Gloucester 1982, ISBN 0-904387-96-8 , pp. 98-99.

- ↑ Alan D. McWhirr: Houses in Roman Cirencester , pp. 222-226.

- ↑ Cosh, Neal: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume IV, Western Britain , pp. 125–129.

- ^ Roger Leech, Alan McWhirr: Roadside Buildings , in: McWhirr, Viner, Wells: Romano-British Cemeteries at Cirencester. Cirencester Excavations II. , Pp. 50-68

- ↑ Nicholas J. Cooper: The Supply of Pottery to Roman Cirencester , In: Neil Holbrook (Ed.): Cirencester, The Roman Town Defences, Public Buildings and Shops , pp. 324-350

- ↑ Jocelyn Toynbee: Art in Roman Britain , London 1961, pp. 7-8.

- ^ McWhirr, Viner, Wells: Romano-British Cemeteries at Cirencester. Cirencester Excavations II.

- ↑ Heidelberg Epigraphic Database

- ^ Roger JA Wilson: A Guide to the Roman Remains in Britain , Constable, London 2002, ISBN 1841193186 , pp. 177-185.

literature

General

- Emil Huebner : Corinium 2. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume IV, 1, Stuttgart 1900, Col. 1232 (outdated).

- Francis Haverfield: Roman Cirencester , in: Archaeologia 69 (1920), pp. 161-209.

- Alan D. McWhirr: Roman Gloucestershire , Gloucester 1981, ISBN 0-904387-63-1 , pp. 21-58.

- John Wacher: The Towns of Roman Britain , Routledge, London / New York 1997, ISBN 0-415-17041-9 , pp. 302–323.

- Stephen R. Cosh, David S. Neal: Roman Mosaics of Britain , Vol. IV: Western Britain , The Society of Antiquaries of London, London 2010, ISBN 978-0-85431-294-8 , pp. 71-125.

Excavation reports

- John Wacher, Alan D. McWhirr: Early Roman Occupation at Cirencester, Cirencester Excavations I , Cirencester 1982

- Alan D. McWhirr, Linda Viner, Calvin Wells: Romano-British Cemeteries at Cirencester. Cirencester Excavations II. Cirencester Excavation Committee, Cirencester 1982.

- Alan D. McWhirr: Houses in Roman Cirencester, Cirencester Excavations III. Cirencester Excavation Committee, Cirencester 1986.

- Neil Holbrook (Ed.): Cirencester, The Roman Town Defences, Public Buildings and Shops, Cirencester Excavations V , Cotswold Archaeological Trust, Cirencester 1998, ISBN 0-9523196-3-2 .

- Neil Holbrook (Ed.): Excavations and observations in Roman Cirencester, 1998-2007, with a review of archeology in Cirencester 1958-2008, Circencester Excavations VI. Cotswold Archeology, Cirencester 2008, ISBN 978-0-9553534-2-0 .

Web links

- Corinium Museum at Google Cultural Institute

- CORINIVM DOBVNNORVM (Eng.)

- Cirencester - Corinium Dobunnorum (English; PDF file; 68 kB)

Coordinates: 51 ° 43 ′ 1.1 ″ N , 1 ° 58 ′ 14.6 ″ W.