Cividale del Friuli

| Cividale del Friuli | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Country | Italy | |

| region | Friuli Venezia Giulia | |

| Coordinates | 46 ° 6 ' N , 13 ° 26' E | |

| height | 135 m slm | |

| surface | 50 km² | |

| Residents | 11,095 (Dec. 31, 2019) | |

| Population density | 222 inhabitants / km² | |

| Post Code | 33043 | |

| prefix | 0432 | |

| ISTAT number | 030026 | |

| Popular name | Cividalesi | |

| Patron saint | San Donato | |

| Website | Cividale del Friuli | |

|

||

Cividale del Friuli ( Furlanic Cividât , Slovenian Čedad , German Östrich ) is a traditional city in the north-eastern Italian Friuli ( Friuli-Venezia Giulia region ) with 11,095 inhabitants (as of December 31, 2019).

Surname

In Roman times the name of the city was Forum Iulii . When the Longobard Empire was finally defeated by the Franks in 776, the city was given the name Civitas Austriae , which means City of the East, as it was located in the eastern part of the Franconian Empire. From this the Italian name Cividale and the German name Östrich developed.

General

Cividale del Friuli is 17 km east of Udine not far from the border with Slovenia on both sides of the Natisone River . Cividale can be reached via the SS 54 state road from Udine to Kobarid (Slovenia) or via the Udine – Cividale railway line.

history

The city was originally a Celtic settlement, which Julius Caesar raised to the status of a city (Latin Forum Iulii , Julius ' marketplace). In the course of the migration of peoples, a population remained in the city that was culturally and through its Furlanic language , which is related to Ladin , with Alpine Romance. Ecclesiastically, Cividale was under the Patriarchate of Aquileja . During the turmoil of the Migration Period, its population suffered particularly, as the city was located immediately to the west of the barriers of the Claustra Alpium Iuliarum in the Birnbaumer Wald , a mountain pass in the Julian Alps that was often used by barbarian peoples as a gateway to Italy.

After the fall of West Rome , the city first belonged to the kingdom of Odoacer , then to the Ostrogothic kingdom of Theodoric and to Byzantium , before it was conquered in 568 by the Lombards , who temporarily established their own duchy there. Around the year 610, Cividale, then part of the Lombard Duchy of Friuli, was sacked by the Avars . After Duke Gisulf II fell in battle, his wife Romilda and her sons sought refuge within its walls. The Avars managed to invade the city. According to the reports of Paulus Deacon , Romilda is said to have opened the gates of the city herself, as she was blinded by the beauty of the barbarian ruler. The male city dwellers were allegedly all killed and the women and children taken into slavery. Only the children of Gisulf managed to escape.

Under the Carolingians , Cividale became part of the Margraviate of Friuli, then the Margraviate of Verona , then came under the rule of the Patriarch of Aquileia before it fell to Venice in 1421 . The rule of the Habsburgs followed (briefly interrupted by a French interlude) and in 1866 the incorporation into the Kingdom of Italy . Cividale del Friuli remained almost unscathed by the earthquake in Friuli in 1976 , although it was exactly on the line of the most haunted places, which stretched on the southern slopes and in the foothills of the Julian-Carnic Alps.

Attractions

Devil's bridge

The Devil's Bridge, the symbol of the city, crosses the Natisone River. The bridge takes its name from the legend of its origins. Then the devil built the bridge over the raging river. As a reward, he should receive the soul of the first to use it. However, after completion, the citizens chased a dog across the bridge. On the river bank, a vault is carved into the stone, known as the Celtic hypogeum , Roman dungeon or Lombard prison.

Piazza del Duomo

In the old town, the Piazza del Duomo is particularly worth seeing. Here is the Palazzo Pretorio or Palazzo dei Provveditori Veneti , the design of which is attributed to Andrea Palladio and which was built between 1565 and 1586. The National Archaeological Museum, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, has been housed there since 1990 . In addition to the rich collection of Lombard finds, parts of the are UNESCO - World Heritage documents belonging Reichenau manuscripts kept. The city palace, built in 1565, is located near the Piazza del Duomo .

Santa Maria Assunta Cathedral

The three-aisled cathedral Santa Maria Assunta (Assumption of the Virgin) from the 14th century was rebuilt after a collapse in 1502 by the architect Pietro Lombardo . In 1909 Pope Pius X elevated the cathedral to a minor basilica . The high altar is adorned with an altarpiece by the Patriarch Pilgrim II (1195–1204). The Latin inscription was made with the help of individual letter punches - over 200 years before the invention of printing with movable letters by Gutenberg . Today's main altar, a table altar without an attachment, stands on an altar island in front of the staircase to the choir in the nave. A life-size wooden crucifix from the 13th century hangs on the north wall of the left aisle.

The Museo Cristiano is attached to the cathedral . a. a Longobard throne and the Callixtus baptismal font can be viewed. Almost even more revealing are frescoes and sgraffito depictions of Lombard life.

Santa Maria Monastery

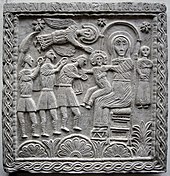

The building complex of the Santa Maria Monastery stands on the steep bank of the Natisone in the old Lombard district of Valle . The Oratorio di Santa Maria from the 8th century was possibly a Lombard palatine chapel. It is therefore also called the Tempietto longobardo . It has a square interior with cross vaults and a barrel-vaulted three-aisled presbytery with medieval, Byzantine-influenced stucco decorations and frescoes. The vault fresco of the choir shows Christ in the mandorla surrounded by saints and a depiction of the adoration of the kings .

Partial view of the stucco figures (depicting the Adoration of the Magi )

Fresco in the vault of the presbytery (Christ in the mandorla surrounded by saints)

More church buildings

The church of San Giovanni in Valle goes back to the palace church of the royal court of the early Lombard times. The Church of Saints Peter and Blasius ( Chiesa dei Santi Pietro e Biagio ) stands out with its frescoed west facade. They date from 1506–1508 and were restored in 2013. In a side chapel, a fresco shows St. Blaise on a throne.

The Chiesa di San Francesco is no longer consecrated and is used for exhibitions.

In the east above the old town, directly on the Slovenian border, is the Madonna del Monte church .

Sons and daughters

- Paulinus II of Aquileia (between 730 and 740–802), Patriarch of Aquileia, grammarian and theologian

- Lorenzo Crisetig (* 1993), Italian football player

- Paulus Diaconus or Paul Warnefried (725 / 730–797 / 799), Longobard historian

- Richard Sbrulius (around 1480 – after 1528), Italian humanist and poet

- Adelaide Ristori (1822–1906), Italian actress

literature

- Roberta Costantini, Fulvio Dell'Agnese, Micol Duca, Antonella Favaro, Monica Nicoli, Alessio Pasian: Friuli-Venezia Giulia. I luoghi dell'arte , pp. 178-183; Bruno Fachin Editore, Trieste

- Silvia Lusuardi Siena: Cividale Longobarda. Materiali per una rilettura archeologica , Milano 2005; ISU Università Cattolica - Largo Gemelli, 1 - Milan

- Andrea Beltrane, Erika Cappellaro, Claudio Cescutti, Daria Labano, Thai Sac Ma, Michele Stocco: Duomo di Cividale del Friuli , Soroptimist International d'Italia. Club di Cividale del Friuli; Copyright 1998 Parrocchia S. Maria Assunta-Cividale

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Statistiche demografiche ISTAT. Monthly population statistics of the Istituto Nazionale di Statistica , as of December 31 of 2019.

- ^ Walter Pohl : The Avars, A steppe people in Central Europe 567–822 AD . 2nd edition Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-48969-9 . (P. 239).

- ^ The province of Friuli after the earthquake , Die Zeit , year 1976, edition 22.

- ↑ Herbert E. Brekle : The typographical production technique of the inscriptions on the silver altarpiece in the cathedral of Cividale , Regensburg 2011

- ↑ Angelo Lipinsky (1986): "La pala argentea del Patriarca Pellegrino nella Collegiata di Cividale e le sue iscrizioni con caratteri mobili", in: Ateneo Veneto , Vol. 24, pp. 75-80 (78-80)

- ↑ Koch, Walter (1994): "Literature report on medieval and modern epigraphy (1985-1991)", Monumenta Germaniae Historica : Aid, Vol. 14, Munich, ISBN 978-3-88612-114-4 , p. 213