Maritime Republics

clockwise from top left:

Venice , Genoa , Pisa , Amalfi

Maritime republics is the collective name for a number of city-states that had their heyday in the Middle Ages in Italy and Dalmatia and played a role as sea power ( thalassocracy ) in the Mediterranean region .

description

In general, the Maritime Republics are understood to mean: the Republic of Amalfi , the Republic of Genoa , the Republic of Pisa and the Republic of Venice . The flags of these four maritime republics have appeared in both the flag of the Italian Navy and the merchant navy since 1946 .

Other maritime republics are: Ancona , Gaeta , Noli and in Dalmatia the Republic of Ragusa .

The maritime republics were usually city-states; they were independent of the powers that were then dominant in Europe. Most of them emerged from the Byzantine Empire , with the exception of Genoa and Pisa. Most of the republics maintained a number of overseas bases throughout the Mediterranean and Black Seas , particularly in Sardinia , Corsica , the Middle East, and North Africa.

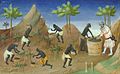

The spice trade, especially with spices from Asia , was a lucrative business from which primarily the Arab states and the Italian maritime republics profited; Spices played an important economic and political role in Europe during the Middle Ages . They were extremely valuable because they were used not only for seasoning, but also as preservatives and the basis of medicines .

The republics are known not only for the history of seafaring and trade: not only rare goods reached their ports, but also news from distant lands and new artistic ideas.

The merchants of maritime republics used gold minted coins that had not been in use for centuries and devised new ways of changing money and accounting. Also, these cities have always been at the forefront of innovation in maritime technology and cartography . The European maps that bring us from the XIV. And XV. They all come from the schools of Genoa, Venice and Ancona ( Portolan ).

- Christopher Columbus - was a Genoese navigator in Castilian service who discovered America in 1492 .

- Leonardo Fibonacci - a mathematician and traveler from Pisa, was familiar with the Arabic-Indian numbers including the zero , introduced them in 1202 with his work Liber abaci .

- Sebastiano Caboto - was a discoverer and cartographer from Venice. Today he is best known for the world map printed on his behalf.

- Giovanni Caboto - from Genoa, Gaeta or Chioggia . After the Vikings , he is considered to be the first European explorer to reach the North American mainland.

- Marco Polo - Venetian trader, traveler and writer, is famous for his trip to China.

- Cyriacus of Ancona - was a humanist and traveler, the forerunner of modern classical archeology and one of the first epigraphers.

- Lancelotto Malocello - was an explorer from the Republic of Genoa; he set up a trading post on the Canary Island of Lanzarote .

History of the Maritime Republics

From the 10th to the 13th centuries, these states built up fleets, which on the one hand served their own protection, on the other hand played a prominent role in Mediterranean trade and as transport fleets during the Crusades . The maritime republics competed with one another, formed changing coalitions and waged wars against one another. The maritime republics were particularly affected by this competitive situation and actively shaped politics in Europe and the Middle East.

Amalfi

The rise of the Duchy of Amalfi began as early as the second half of the 10th century. During the First Crusade in 1096, the duchy established itself together with the other sea cities as an economic power in Egypt , where they exchanged slaves, iron and wood for gold, which they there and in the Levant and in Constantinople for silk, alum, purple and Trade cotton.

Little by little, a large trading network was created in the Mediterranean region (see maps).

In 1073 Amalfi lost its independence and fell to the Normans . Robert Guiskard took on the title dux Amalfitanorum . Two uprisings to regain independence (1096–1101) and (1130–1131) failed. The great times of Amalfi ended with the sacking of the city by Pisa in 1135 and 1137. In the centuries that followed, Amalfi could no longer find its way back to its old prosperity.

Genoa

The heyday of the Republic of Genoa began in the 11th century with the expulsion of the Arabs from Sardinia , which was carried out together with Pisa. Through the crusades , Genoa also gained significant economic and political power and soon secured its first trade privileges in the Levant through supplies for the crusaders on the sea route to Antioch . The former ally and now a major competitor Pisa was able to defeat Genoa in a war (1118–1133) and concentrate on the power struggle with its last major competitor, Venice. With the Agreement of Nymphaion in 1261 and the end of the Latin Empire of Constantinople , the Genoese were able to head to their colonies and bases in Salé , Spain , Cyprus and the Levant as well as bases and trading centers in the Black Sea, which brought the republic enormous advantages and opportunities.

Genoa was linked to Venice by centuries of competition, which finally came to an end after four naval wars in the Chioggia War in the final defeat of Genoa in 1381.

In 1796 Napoleon Bonaparte occupied Genoa and a year later founded the Ligurian Republic .

Pisa

The Republic of Pisa also benefited greatly from the First Crusade and was able to establish trading centers on the Levant coast.

After the Arabs had been driven out of Sardinia together with Genoa, however, the republic saw its position threatened by the other sea cities.

Pisa finally succeeded in wrestling Amalfi in 1137, but competition with Genoa remained threatening.

After the defeat by Genoa in 1133, Pisa's heyday slowly came to an end. Pisa also waged wars against Florence up to 1259, which further weakened the republic. Genoa suffered the final blow in the Battle of Meloria in 1284, after which Pisa could no longer properly recover.

In 1509, Florence and its troops camped on three sides of the beleaguered city, which finally had to surrender due to the famine on June 8th, 1509. From then on, the Florentines remained masters of Pisa.

Venice

Similar to the other maritime republics, the rise of the Republic of Venice to a great power began around the year 1000. As one of the last Italian maritime cities to take part in the First Crusade, Venice felt the power of the competing maritime republics early on. In addition to conflicts with Pisa, Genoa soon became the main enemy in the race for colonies and trade bases in the eastern Mediterranean. With the support of the Fourth Crusade and the establishment of the Latin Empire in 1204, Venice significantly expanded its supremacy in the Mediterranean region. It was only with the collapse of the Empire in 1261 that Venice was ousted from the Black Sea area in favor of Genoa. Four naval wars followed, in which Venice and Genoa severely weakened each other. With the victory of Venice over Genoa in the Chioggia War in 1381, Venice was finally able to prevail. The importance of the Serenissima as a major commercial power declined in the early modern period, however, in view of the development of new trade routes to the west and the loss of importance of the Venetian colonies and bases in the Mediterranean and the Levant.

In the Treaty of Campoformio of October 17, 1797, Veneto , Dalmatia and Istria fell to Austria as the Duchy of Venice , and the Republic of the Ionian Islands to France. On January 18, 1798, the occupation of the city by the Habsburg Monarchy began with the entry of his troops .

Ancona

Towards the end of the 11th century, Ancona was a free city-state and competed with the other maritime republics. The Republic of Ancona was allied with the Republic of Ragusa and the Byzantine Empire . The city competed with the Republic of Venice, which did not accept free ports in the Adriatic .

Ancona had deposits and consulates in Constantinople , Alexandria , Asia Minor , Cyprus , Tripoli , Spain and the Aegean Islands .

In 1173 Ancona was besieged by Christian I von Buch , Archbishop of Mainz and Arch Chancellor of the Holy Roman Empire . The imperial army was allied with the Republic of Venice . Ancona successfully survived the siege after months of resistance. After the siege, an economic and cultural boom began. The basis was the sea trade with the eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea . During this time, public buildings and churches were built.

In 1532 the city passed to the Papal States: Pope Clement VII used the newly built citadel to secure his power.

Ragusa

With the decline of Byzantium , the Republic of Venice began to see the city-state as a rival and tried to conquer the city in 948. However, this attempt failed. The residents of the city believed that the city was saved by St. Blaise , who has since been venerated as the city's patron saint.

When the Hungarians attempted to drive Venice out of Dalmatia in 1347 and the army of King Louis the Great advanced far into Herzegovina , Ragusa submitted to the Crown of St. Stephen . In 1358, the city republic recognized the sovereignty of the Hungarian-Croatian king, but maintained extensive independence.

In 1433 and 1458, the republic concluded a peace treaty with the Ottoman Empire and committed to paying tribute. In addition, she undertook to send ambassadors to the Sultan's court . In 1481 the city came under the protection of the Ottoman Empire and in return undertook to pay tribute of 12,500 ducats . In return, their merchant ships were given permission to sail into the Black Sea , which was forbidden to other non-Ottoman ships. The city-state received diplomatic support from the Ottoman Empire in relation to the Republic of Venice. In return, Ragusa became an important trading port for the Ottomans. Florentine goods were transported to Ragusa by sea via the ports of Ancona .

In 1806 the Republic of Ragusa ended; it entered the Illyrian provinces of France.

Maps of sea routes and trade centers

literature

- Gino Benvenuti: Le Repubbliche Marinare. Amalfi, Pisa, Genova, Venezia. La Nascita, le Vittorie, le Lotte e il Tramonto delle gloriose Città-Stato che dal Medioevo al XVIII Secolo dominarono il Mediterraneo (= Quest'Italia. Collana di storia, arte e folclore. Vol. 143, ZDB -ID 433075-4 ) . Newton Compton, Rome 1989.

- Heymann Chone: The trade relations of Emperor Friedrich II. To the seaside cities Venice, Pisa, Genoa. Berlin 1902.

- Peter Feldbauer, Gottfried Liedl, John Morrissey: Venice 800-1600. The Serenissima as a world power. Vienna 2010.

- Arsenio Frugoni: Le Repubbliche Marinare (= ERI classe unica. Vol. 13). ERI, Turin 1958.

- Paolo Gianfaldoni: Le antiche Repubbliche marinare. Le origini, la storia, le regate (= CDGuide 11). CLD, Fornacette di Calcinaia 2001, ISBN 88-87748-36-5 .

- Hans-Jörg Gilomen : Economic History of the Middle Ages. Munich 2014.

- Arne Karsten : History of Venice. Munich 2012.

- Hermann children, Werner Hilgemann : dtv-Atlas world history. Volume 1: From the beginnings to the French Revolution. Munich 2007.

- Armando Lodolini: Le Repubbliche del mare. Ente per la diffusione e l'educazione storica, Rome 1963.

- Manfred Pittioni: Genoa - the hidden world power. Vienna 2011.

- Volker Reinhardt : The Renaissance in Italy. History and culture. Munich 2012.

Web links

- Republish marinare

- Le repubbliche marinare

- Coins of the old maritime republics

- Le navi del medioevo (Ships of the Maritime Republics in the Middle Ages). Retrieved July 15, 2018 (Italian).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Joachim-Felix Leonhard : The seaside city of Ancona in the late Middle Ages: Politics u. Handel , Niemeyer, Tübingen 1983

- ^ Lazio guida rossa del Touring Club Italiano. Touring Editore, 1981. p. 743.

- ^ Anne Conway, Giuliana Manganelli, Liguria: una magica finestra sul Mediterraneo White Star, 1999.

- ↑ Croazia. Zagabria e le città d'arte. Istria, Dalmazia e le isole. I grandi parchi nazionali. Touring Editore, 2004

- ↑ Christa Pöppelmann: General education world history for dummies. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim 2017. online

- ^ Konrad Kretschmer : The Italian Portolane of the Middle Ages: a contribution to the history of cartography and nautical science , reprint of the Berlin 1909 edition, Hildesheim 1962.

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Gilomen: Economic history of the Middle Ages. Munich 2014, p. 84 f.

- ^ A b Hans-Jörg Gilomen: Economic history of the Middle Ages. Munich 2014, p. 85.

- ↑ Manfred Pittioni: Genoa - the hidden world power. Vienna 2011, p. 46.

- ↑ Manfred Pittioni: Genoa - the hidden world power. Vienna 2011, p. 50 ff.

- ^ Hermann children, Werner Hilgemann: dtv-Atlas world history. Volume 1. Munich 2007. p. 183.

- ↑ Arne Karsten: History of Venice. Munich 2012. p. 32 ff.

- ↑ Heinz Kramer, Maurus Reinkowski: Turkey and Europe: a changeful relationship history. W. Kohlhammer Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-17-018474-9 , p. 55 (limited preview in Google book search)