Bessarabian Germans

The Bessarabian Germans are a German ethnic group who lived in Bessarabia (now divided between the Republic of Moldova and Ukraine ) between 1814 and 1940 , but are no longer represented there today, apart from a few individuals. Around 9,000 people immigrated to Bessarabia between 1814 and 1842 from Baden , Württemberg , Alsace , Bavaria and parts of Prussia that are now part of Poland . The area on the Black Sea was then part of the Russian Empire as New Russia , later it became the Gouvernement of Bessarabia .

In their 125-year history, the Bessarabian Germans were an almost purely rural population. With three percent of the population at the beginning of the 20th century, they were a minority . Covered by the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939, Bessarabia was militarily occupied by the Soviet Union in the summer of 1940 . At the end of 1940, the Bessarabian Germans with around 93,000 people almost completely followed the call to resettle in the German Reich under the motto Heim ins Reich .

The most prominent representative of this ethnic group is the former German Federal President Horst Köhler . His parents lived in the German colony Ryschkanowka in northern Bessarabia until they were resettled in 1940 . They then lived temporarily in a camp in the German Reich and were finally settled in occupied Poland from 1941 , where Horst Köhler was born in 1943.

origin

recruitment

In the sixth Turkish war between 1806 and 1812, troops of the Russian Tsar Alexander I conquered Bessarabia. He established the Bessarabia governorate , the smallest of the tsarist empire, in what was once the eastern part of Moldova. The capital became the Central Bessarabian Kishinew .

Nomadic Tatar tribes from the southern part of Bessarabia, the Budschak , were expelled after the Russian conquest or left voluntarily. The area was then sparsely populated and largely unused. To colonize the fallow but fertile land, Russia began recruiting foreign settlers from 1813 onwards. Russian subjects were serfs until 1861 . The recruits were supposed to improve agriculture on the fertile black earth.

On November 29, 1813, Tsar Alexander I issued a manifesto in which he promised German settlers the following privileges, some for ever :

- Land donation

- Interest-free loan

- Tax exemption for ten years

- Self-management

- Religious freedom

- Freedom from military service

The offer was made to German settlers in the Wartheland , especially near Łódź , in the Duchy of Warsaw . Hence, they were later called Warsaw Colonists . They came from Prussia, Württemberg and Baden and were recruited by Prussia after the partition of Poland . They had only settled there a few years earlier. The tsar had become aware of their desolate situation in the pursuit of the Grande Armée .

The second wave of emigration to Bessarabia came from southwest Germany , especially from Württemberg . The emigrants were invited to southern Russia by advertisers from the Russian crown. Emigration reached its peak around 1817/18, after the emigration ban in Württemberg was lifted in the year without the summer of 1816.

Reasons for emigration

Reasons for emigration in the Duchy of Warsaw were:

- Politically

- Life under Polish rule

- Economically

- Deterioration in the economic situation

The Germans in the Duchy of Warsaw had recruited Prussia to colonize the territories after the partitions of Poland . After the peace of Tilsit the position of the settlers deteriorated due to state pressure. They therefore willingly followed the tsar's recruitment and promises.

Reasons to emigrate in southwest Germany were:

- Politically

- Military and war services for the Napoleonic foreign rule

- Labor service

- Oppression by the authorities

- Economically

- Harvest failures , famines

- high tax burden because of the noble court

- Land shortage due to inheritance

- Religious

emigration

From the northeast

The number of German emigrants from northeast Germany and from the German settlement areas in Poland is estimated at around 1,500 families. They preferred the overland route by horse and cart and suffered less from infectious diseases during the journey. They were the first Germans in Bessarabia in 1814 and were called Warsaw colonists because of their origins .

From the southwest

Between 1814 and 1842 around 2000 families with a total of around 9000 people emigrated to Bessarabia in southern Russia from regions in southwest Germany . The emigration from the areas of Württemberg , Baden , Alsace , Palatinate and Bavaria with the peak in 1817 was called the Swabian procession. After the passports were issued by the German authorities, they began their journey in larger groups, so-called columns . The travel time for the approximately 2000 kilometers long route was two to six months, depending on the route. Many of the emigrants with religious reasons for emigration formed so-called harmonies . The ship journey began on the Danube , for which the emigrants moved by land to Ulm . There they embarked on the one-way ship type of Ulmer Schachteln , which drifted downstream as a nauffahrt . Many emigrants fell ill with infections and died during the voyage. The journey led downriver to the Danube Delta shortly before the mouth of the Black Sea . A week-long open-air quarantine on a river island off the city of Ismajil ( Odessa Oblast , Ukraine ) resulted in further deaths. About 10 to 50 percent of the emigrants are said not to have survived the voyage.

Colonization work under Russian rule

Settlement

Tsarist Russia settled the German emigrants in Bessarabia according to plan. In southern Bessarabia, they were given areas totaling 1500 km² on the vast, treeless steppe areas of the Budschak . In the parlance of the Bessarabian Germans it was crown land because it was made available by the Russian "crown" (the tsar). In the first settlement phase until 1842, 24 German (mother) colonies emerged. The corridors and settlement areas as well as the layout of the settlements were specified by the Russian settlement authority. The newly created villages all had the same layout as a street village . Most of the settlements were laid out in an elongated valley with gently rising hills. Very few newcomers found so-called crown houses in the country , which had already been built by the Russian state (the “crown”). In the beginning they usually lived in self-dug earth huts. Even the arrival was a disappointment, because the emigrants came across a barren land with high grass, thistles and weeds. Herds of cattle from Moldovan tenants moved across the vast land, destroying the settlers' fields.

Self-management

The self-government of the German settlers promised by the tsar when recruiting was headed a special Russian administration called the Welfare Committee for the Colonists of Southern Russia (previously: Guardianship Office for Foreign Settlers in New Russia ). It was the resettlement staff for all new settlers, which also accompanied the further development in the Black Sea area. The seat was initially in Kishinev and from 1833 in Odessa . The official language of the authority was German . It included a president and around 20 employees (civil servants, translators, doctors, veterinarians, surveyors). The settlement and promotion of the settlers was at the same time a Russian model attempt to gain experience. These should benefit the own, backward agriculture in times of serfdom .

Presidents of the welfare committee were:

| Surname | Term of office |

|---|---|

| General Ivan Insov | 1818-1845 |

| State Councilor Eugene von Hahn | 1845-1849 |

| Baron von Rosen | 1849-1853 |

| Baron von Mestmacher | 1853-1856 |

| Islawin | 1856-1858 |

| Alexander von Hamm | 1858-1866 |

| Th. Lysander | 1866-1867 |

| Vladimir von Oettinger | 1867-1871 |

In addition to the settlement, the Welfare Committee upheld the settlers' rights and oversaw their duties to the Russian government. The German settlers generally viewed the facility as beneficial as it restricted the initial arbitrariness of the corrupt Russian administration. As promised during the recruitment process, the authorities supported the settlers as long as they were not yet fully economically viable. There were small sums of money, food and materials such as a cart, plow, and work tools. In practice, however, the funds trickled away into the corrupt Russian administration.

The colonists were subject to the colonization law introduced by Catherine the Great in 1764, but in criminal matters they were subject to state jurisdiction. When the Tsar lifted the colonist status in 1870, the Welfare Committee was dissolved in 1871. Below the welfare committee, there were 17 regional offices ( Wolost ) for the approximately 150 German communities , with an elected regional head (Oberschulz) , two assessors and a clerk. Her duties included the administration of the fire and orphan funds. The court at this level was called the Volost Court , which consisted of a judge and three assessors.

The villages were administered by the Dorfschulz ( mayor ) and two assessors, who elected the male landowners of the village for three years each. In addition to compliance with discipline and order, the village schoolteacher had to enforce official ordinances and supervised inheritance and orphan matters. He was assisted by two or more auxiliary policemen, the village guard and a village clerk who knew the law.

Place naming

Originally the colonies were named according to the numbers of the measured land, such as Steppe 9, Colony No. 11, The Twelfth . After that, the newly founded communities gave themselves names that were based on foreign language names for terrain features such as rivers, valleys and hills. From 1817, the welfare committee gave the newly founded villages so-called memorial names. These designations were reminiscent of the places of victorious battles against Napoleon in the Patriotic War and the Wars of Liberation , such as Tarutino , Borodino , Beresina , Arzis , Brienne , Paris , Leipzig , Teplitz , Katzbach , Krasna , Wittenberg (originally Malojaroslawez ). Due to the variety of place names, several names existed for several places.

In a later phase of the German establishment of localities from around 1850, the settlers named their villages according to their own hopes (Hope Valley, Peace Valley) or religious motifs ( Gnadental , Lichtental). Numerous German village foundations also adopted terms of Turkish- Tatar origin, such as Albota (white horse), Basyrjamka (salt hole), Kurudschika (dry).

Settlement development

The living conditions of the colonists were harsh in the early days, despite the privileges granted. The first dwellings were primitive mud huts or even holes in the ground with a thatched roof. Unfamiliar climates and diseases wiped out entire families. Plagues of the land hampered the reconstruction. This includes the following events: animal diseases (1828/29, 1834, 1847, 1859-60), floods , epidemics of plague (1829) and cholera (1831, 1853, 1855), poor harvests (1822-24, 1830, 1832-34) , Heavy frosts (1828), beetle plagues (1840–47), as well as grasshoppers and mouse plagues . In 1827 and 1828 the population had to bear the burden of the Russian army marching through in the Russo-Turkish War . It was not until the second half of the 19th century that there was a regulated and independent life in the economic, cultural and religious areas in the German settlements. In connection with agricultural skills, a favorable climate and good soil, an economic upswing set in, according to the saying "The first generation has death, the second the need and the third only the bread". The characteristic traits of the ethnic group such as hard work , piety, having a large number of children and thrift also contributed to this.

The first 24 villages of German emigrants were called mother colonies. They emerged as part of the Russian state colonization. The approximately 125 settlements that arose after 1842 (including manors and hamlets) were called daughter colonies . They were due to private settlement activities of the Bessarabian Germans already living in the country. The first 24 colonies were:

| Settlement no. | settlement | founding |

|---|---|---|

| number 1 | Borodino | 1814 |

| No. 2 | Krasna | 1814 |

| No. 3 | Tarutino | 1814 |

| No. 4 | Kloestitz | 1815 |

| No. 5 | Kulm | 1815 |

| No. 6 | Wittenberg | 1815 |

| No. 7 | Berezina | 1815 |

| No. 8 | Leipzig | 1815 |

| No. 9 | Katzbach | 1821 |

| No. 10 | Paris | 1816 |

| No. 11 | Old-Eleven | 1816 |

| No. 12 | Brienne | 1816 |

| No. 13 | Teplitz | 1817 |

| No. 14 | Arzis | 1816 |

| No. 15 | Sarata | 1822 |

| No. 16 | Alt-Posttal | 1823 |

| No. 17 | New Arzis | 1824 |

| No. 18 | New Eleven | 1825 |

| No. 19 | Mercy Valley | 1830 |

| No. 20 | Lichtental | 1834 |

| No. 21 | Dennewitz | 1834 |

| No. 22 | Peace Valley | 1834 |

| No. 23 | Plotzk | 1839 |

| No. 24 | Hope Valley | 1842 |

A list of about 150 settlements founded and inhabited by Bessarabian Germans, including manors, can be found at:

Tarutino , Arzis and Sarata emerged as the center of the Bessarabian German settlements . Tarutino was the largest village and had several central institutions. This included the German People's Council , the German Business Association (until 1931) and two of the three higher schools (Evangelical-German Girls 'School and Evangelical-German Boys' School). At the time of the resettlement in 1940, the place had the largest number of residents with 3700 Bessari-German residents. Another 2,100 non-German residents lived in the village. The second most important place was the Sarata settlement with 2100 German and 700 non-German residents. The Werner School was the only teacher training institute in the region. There was an important weekly market and larger businesses in Arzis. The place was of central importance because of the seat of the German Business Association (from 1931), which carried out advanced training courses.

Other larger settlements were Krasna (3500 residents of German descent), Klöstitz (3200), Borodino (2700), Beresina (2600), Teplitz (2500), Leipzig (2300), Friedenstal (2200), Lichtental (2100) and Hope Valley (1900) .

Population development

- 1826: 9,000 people

- 1862: 24.160

- 1897: 60,000

- 1919: 63,300

- 1930: 81,100

- 1940: 93,300

geography

The main settlement area of the Bessarabian Germans was in the southern part of the country in the steppe-like area of the Budschak in southern Bessarabia. It was a gently rolling hill country that was largely free of trees until the 20th century. The settlers planted acacia forests and strips of wood near their villages to protect the arable land against wind and erosion. The villages were mostly on steppe rivers flowing southwards. Since it was fed by the snowmelt in areas to the north, they usually dried up in summer.

Agriculture and ranching

In accordance with the recruitment of the Tsar, almost all of the newcomers were initially farmers who worked on their own land. Each German family received 60 desjatines (about 65 hectares) of crown land from the state as heritable arable land. The settlement area of the Germans in southern Bessarabia, the Budschak , was in the southern Russian black earth belt . Its deep, dark soil is one of the most fertile arable soils that do not require any fertilization. The harvest was not always secure because of the dry steppe climate. The main pests for agriculture were the ground squirrel (also known as the earth hare), the common hamster and swarms of locusts . Natural disasters were rare earthquakes (1940) and floods caused by rivers carrying floods after the snowmelt or summer downpours (Kogälniktal, 1926).

The arable land was called steppe because the landscape was almost tree-free. The main crops were cereals , maize , legumes (soy) and oil fruits (sunflowers). The main products were further processed in mills on site or brought to the next larger cities of Odessa and Akkerman .

Wine-growing in particular brought economic success , as the deep-rooted vines survived longer periods of drought. The gently rolling slopes of the Bessarabian hill country offered favorable cultivation conditions. In some colonies large areas of wine were grown (see Viticulture in the Republic of Moldova ), which was particularly the case in the Schabo colony . The place, founded in 1822 by winemakers from the Swiss canton of Vaud , quickly developed into one of the leading winemaking places in Russia. Every peasant economy of German origin grew wine on the farm property for their own use. Each farm was mostly self-sufficient , which also had its own fruit, vegetable and herb garden.

The Germans only kept livestock on a small scale, because the manure was not needed due to the high fertility of the soil. As far as it was available, it was dried and used as fuel in winter. Sheep farming was more widespread, especially the fine-wool Karakul sheep . The typical black fur hats ( karakul hats ) of men could be made from the fur . The keeping of poultry for self-sufficiency was a matter of course on every farm.

In contrast to the Moldovan population, the Germans used the horse instead of the ox as a draft animal . From their youth and with great affection, they were attached to these animals, which, so to speak, belonged to the family. The old Arab horse was bred, similar to the Arab thoroughbred . The colonist horse was suitable for farm work as well as for riding and in a team for the carriage or the sleigh. When the Bessarabian Germans were resettled in 1940, the entire horse population, with the exception of individual breeding animals, remained in Soviet-occupied Bessarabia.

Cattle breeding was practiced to a lesser extent by German settlers. At first it was carried out with the native steppe cattle , later with the red steppe cattle from Molotschna and from 1918 with the angler cattle .

kitchen

The cuisine of the Bessarabian Germans was subject to several influences. It initially developed from the recipes brought from Germany. Later, because of the neighborhood, the dishes of other nationalities were taken over or changed. Certainly the cuisine was based on fruits typical of the country, for example paprika and watermelons. The national dish is the flour and potato dish Strudla , which goes back to Bulgarian settlers in Bessarabia. Another well-known dish is krautwickel (Kaluschke, Holubzi), which comes from Ukrainians. Steam noodles, pepper sauce and stuffed peppers were also known. Borsch were taken over by the Russians, Mamaliga by the Romanians. As a side dish, there were pickles such as tomatoes and pickles .

Way of living

The Bessarabian Germans were mostly farmers and lived in villages on their farms . The village, property and house forms of the colonist villages were very similar. The farms were on an acacia -lined road up to 50 m wide . This street was often only crossed by a cross or cross street in the central area of the village, where the church or the prayer house and school were located.

The structure of a typical German settlement can be seen in the village of Hannowka .

Property

The plots were designed very generously in terms of area, as most of the villages were street villages with only one street. The street front was 25 to 50 m. The plots stretched 100 to 500 m deep. In addition to the buildings, there were farm areas (threshing floor, hay barn) on the property. In the rear part of the property there was mostly a large vineyard in addition to garden areas.

building

The main building of the courtyard was the elongated single-story colonist house. It was a house with a 5 to 10 m wide gable front and a total length of about 25 m. The gable almost always faced the street. In the front area to the street were coreless rooms (rooms, kitchen), behind them stables and sheds were attached. On many farms there was a small building in which people cooked in the warm season and ate in the courtyard next to it, the summer kitchen . There was also a separate cellar. The building material for the houses was stone extracted from quarries or mud bricks dried in the sun . The buildings plastered with clay were always whitewashed with lime. The roofs were mostly covered with reeds , later with cement tiles. On the farm yard there were stables, a threshing floor as well as a storage and wine cellar. In the rear part of the property were vegetable, fruit and vineyards.

Inland colonization with new settlements

With the establishment of the last colony (Hope Valley) in 1842, the influx of emigrants from Germany stopped and the state, Russian colonization ended. After that, internal colonization began in the country through private settlement activity. The arable land of the 24 mother colonies had become scarce due to population growth. In Bessarabia there were many landless sons looking for farmland, since according to inheritance law only the youngest son inherited the father's farm. The Bessarabian Germans bought or leased land from large Russian landowners and founded new villages, so-called daughter colonies .

The most important representatives of inland colonization were the brothers Gottfried Schulz and Gottlieb Schulz , who appeared towards the end of the 19th century. They had amassed a great deal of capital through cattle trading and used it to buy land from aristocratic Russian landowners. Most of them lived in St. Petersburg and lived a lavish life in French and Swiss health resorts, which in some cases they could no longer pay for by renting their lands. The brothers sold the land to their compatriots of German descent. One percent of the purchase price is said to have been charged as a commission. By buying and selling land, the inhabitants of 60 Bessarabian German villages became owners of the land they had previously leased. Numerous new Bessarabian German settlements emerged on the purchased land.

There were further local foundings from 1920 as a result of the Romanian agricultural reform . Large landowners with more than 100 hectares of land were expropriated. Their land was distributed to landless people who received 6 hectares each. Settlements called hectare villages were then established on the land that had become vacant .

Due to the different types of settlement, around 150 German settlements and manors were created during the presence of the Germans in Bessarabia between 1814 and 1940.

Bessarabian German institutions

church

here: Bessarabian German settlement Hannowka

Church and religion shaped the lives of all Bessarabian Germans intensively, because many of their ancestors had once left their German homeland for religious reasons. In 1804, the Russian colonial administration had prescribed a community order for the new settlers, which declared religious obligations to be the most important. The village mayors were required to monitor the regular Sunday worship services. The pastors belonged to the intellectual leadership class and enjoyed unrestricted authority, even after the resettlement in 1940 and in what was later to become the Federal Republic. In practice, the use of the Bible and hymn book contributed to the fact that the German language was preserved abroad.

A house of worship was built as the first community facility for newly founded settlements. The settlers raised enormous sums of money and work for this. A total of 120 church buildings were built. In some larger parishes, stately church buildings were built , initially in the classical style , later in the neo-Gothic style for up to 1000 visitors. In most of the villages prayer houses were built, which also included the sexton's apartment and the village school. The colonists carried the maintenance for the church, school, sexton and teacher (mostly a sexton teacher in double functions). Since many emigrants came from Württemberg, where Pietism was widespread, there were meetings of hour workers in many settlements .

A special case of the religious life of the Bessarabian Germans was the charismatic preacher and well-known representative of the revival movement Ignaz Lindl , who founded the community of Sarata with his followers in 1822. He exerted a strong attraction on the colonists, who made pilgrimages from up to 80 km away for his Sunday sermons.

Church organization

When the resettlement took place in 1940, the ecclesiastical organization of around 150 German settlements consisted of 13 parishes and three parishes of Evangelical Lutheran denomination. Each parish had a pastor who was responsible for several parish villages. In addition, there was a reformed parish in Schabo for the settlers from Switzerland . From 1876 there was a Baptist church with seven branches (Friedenstal, Kamtschtka, Kantemir, Seimeny, Kisil, Mariewka, Hantscheschti). There was also a Roman Catholic church district with four parishes (Balmas, Emmental, Krasna, Larga). These belonged to the Diocese of Cherson , founded on July 3, 1848 , which was renamed the Diocese of Tiraspol shortly afterwards .

The Russian state actively supported a self-determined ecclesiastical life for the new settlers as early as the early 19th century. At that time, Tsar Alexander I was planning a constitution for the Lutheran congregations for the settlers in the Black Sea region. In 1832, his successor Nicholas I created a law that reorganized the order of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Russia. As a result, Bessarabia ecclesiastically belonged to the First South Russian Provost District of the Consistory in St. Petersburg with its seat in Odessa. This church facility was under the control of the Russian Interior Ministry. Many of the clergy appointed by the Russian state, such as Rudolf Faltin , were of German-Baltic origin and had studied theology at the German-speaking university in Dorpat .

When Bessarabia separated from Russia in 1918 and joined Romania, the church organization also changed. An Ev.-Lutheran was formed. Regional Church of Bessarabia , which was part of the Ev. Regional Church in Romania . Spiritual heads in Bessarabia during the inter-war period were pastor Daniel Haase until 1936 and Immanuel Baumann from 1939 .

School classes and educational institutions

Initially, the colonists taught their children in their own farmhouses. Later, teachers employed by the community (and mostly poorly paid) gave lessons in prayer rooms or teacher's apartments. It included reading, writing, arithmetic and religious instruction as a major .

The close connection between the religious institution of the church and the political institution of the village community, which is typical in Bessarabia, is also evident in the school system . The schools were subordinate to the church from the beginning, and they were built and maintained by the village community. There was also a spatial connection. In smaller congregations without a church there were prayer houses for worship , in which school lessons also took place. Church and congregation were intertwined by the type of sexton school with the sexton teacher . He taught the children and performed church activities when the pastor was absent .

The Werner School , which was established in Sarata around 1850, trained Bessarabian German teachers and increased the level of teaching. Since the schoolchildren all did child labor in their parents' fields, most of the lessons only took place in the winter months.

Initially, the Bessarabian German school system was completely autonomous in the hands of the colonists, according to the will of the Russian settlement authorities, so that the language of instruction was German. From around 1880, Russian was introduced as a compulsory subject as part of efforts to become Russification . Although the schools were formally under Russian state supervision, they remained under ecclesiastical German influence. After belonging to Romania from 1918, the state began to try to Romanize the school system. Romanization was also used for de-russification. The Romanian state appropriated the school buildings, converted them into elementary schools and paid the teachers. The German language of instruction was more and more replaced by Romanian, as were German teachers by Romanian. German lessons were only given on a voluntary basis as teachers work overtime. Exceptions were the higher high school similar schools in Tarutino and the Werner-school teacher training in Sarata. From 1937 onwards there were easing of the Romanian school policy. The German language was increasingly reintroduced into the school and in 1939 the expropriated school buildings came back into the possession of the municipalities by royal decree.

School-system:

- Elementary schools in (almost) every German village

- Evangelical-German teacher training institute Werner in Sarata, opened in 1844, named after the Württemberg merchant Christian Friedrich Werner , who bequeathed his fortune to the community. The school served to train German school teachers and was the first German-speaking teacher training institution in the Russian Empire.

- Evangelical German Girls' School ( Higher School for Daughters ) in Tarutino, opened in 1878

- Evangelical-German boys' lyceum in Tarutino, opened in 1906

- Farm school in Arzis, opened in 1935

Healthcare

Since the German settlement of Bessarabia in 1814, the health system was inadequate because of the lack of medical care. In the villages there were only midwives and lay doctors who were referred to as field scissors . The most common diseases were tuberculosis , typhus , anthrax , trachoma and malaria . In 1937, the mortality rate among young people was above average in comparison with the German Reich. Infant mortality and that of young people was three times higher, that of children between the ages of one and fourteen even five times higher than that in the German Reich.

Facilities:

- The Alexander-Asylum charity in Sarata, (later Alexander-Stift in Großerlach ), founded in 1865 by six pastors, named after the then ruling Tsar Alexander II. Home for old, sick and handicapped people as well as orphans , financed from collections from German villages in Bessarabia .

Banking

The first credit institutions in Bessarabia emerged from 1880, which soon flourished thanks to the liberal legislation of the Tsarist Empire. In the Romanian period after the First World War, cooperative-based Volksbanks were established under names such as Cornelia, Minerva, Veritas. With around 80 percent of the farms, a large part of the population of Bessarabia was affiliated with them as cooperative members.

Other financial associations were orphans' funds in German villages, which in 1940 only existed in eight villages. They managed orphans' assets. The first orphan and savings bank was established in 1830, and in 1869 it was available in all Bessarabian German areas.

Press

During the time when Bessarabia belonged to Russia, the " Odessa newspaper" , founded in 1863, was the most widely read newspaper. After belonging to Romania, some German teachers founded the "German newspaper Bessarabia" in 1919. In 1935, the "Deutsche Volksblatt" was created as a rival paper, which transported the ideology of the National Socialist renewal movement. The “Dakota Free Press” was also read as a link to the Bessarabian Germans who emigrated to the USA. As an important organ of the cultural cohesion of the population group, the home calendar, which is published annually to this day, acted from 1920.

politic and economy

- German People's Council , with its seat in Tarutino, founded in 1920 as an association of Romanian citizens of German ethnicity to protect their interests (counterpart to the Romanian pressure of the Romanian state against minorities)

- Community Association , (today Bessarabian Community Association ), formed in 1823 from awakened and pietistic circles ( students and brother assemblies )

- German trade association , based in Tarutino, founded in 1921 as an amalgamation of German cooperatives to eliminate middlemen in Bessarabia

coat of arms

The coat of arms of the Bessarabian Germans was only created after the resettlement in 1940 and after the Second World War . It symbolizes the abandoned home on the Black Sea.

It is quartered:

- in field 1 a black draw well in the silver field

- fields 2 and 3 are divided into blue and gold

- in field 4 there is a rearing black horse in the silver field

- in the center is the coat of arms with a red central shield with two golden ears of wheat, this is covered with a golden Latin cross .

The meanings of the coat of arms are:

- Blue symbolizes the blue sky over the steppe.

- Gold stands for the golden fields of wheat in the wide landscape.

- Red is borrowed from the flag of Romania; the state to which the Bessarabian Germans were obliged as loyal citizens.

- The steppe well shows how important drinking water was for people and animals in a dry climate.

- The cross is a symbol for the church and the pronounced faith.

- The ears of wheat on the cross are a sign of the result of the hard work and symbolize daily bread.

- The horse indicates the farmer's most loyal helper, with whom he cultivated the fertile black earth soil .

Culture and leisure

- Local history museum in Sarata (today the local history museum of the Bessarabian Germans in Stuttgart), founded in 1922, around 700 museum pieces from the history of the ethnic group.

- Bad Burnas health resort between the Black Sea and the Burnas Liman , founded in 1925, up to 18,000 spa guests per season, use of the salt liman , which is rich in medicinal mud, with several rest homes for Bessarabian German children, teachers and pastors.

Bessarabic culture

Home song

The text and melody of the Bessarabian Heimatlied are from Albert Mauch. He wrote it in 1922 as director of the Werner Seminar, the German teacher training institute in Sarata .

God bless you my homeland!

I howdy thousand ,

The land where my cradle was

By my fathers choice!

You country, so rich in everything,

I locked you in my heart

I stay the same with you in love

In death I am yours!

So shield, God, in joy and sorrow,

You our homeland!

Keep the fields fertile

Up to the Black Sea beach!

Will you keep us German and pure,

Send us a friendly lot

Until we rest with our fathers

In your home lap!

Important representatives of the ethnic group

- Christian Friedrich Werner (1759–1823), founder of the Evangelical German Teacher Training Institute Werner ( Werner School ) in Sarata

- Ignaz Lindl (1774–1845), priest and founder of Sarata

- Alois Schertzinger (1787–1864), co-founder of Sarata

- Rudolf Faltin (1830–1918), Protestant parish pastor in Kishinew and supervisor of the diaspora communities in the parish

- Gottfried Schulz (1846–1925), cattle dealer and, as a large landowner, the initiator of Bessarabian German settlements

- Gottlieb Schulz (1853–1916), cattle dealer and, as a large landowner, initiator of Bessarabian German settlements

- Andreas Widmer (1856–1931), Duma member of the 1st Duma (April – June 1906)

- Johannes Gerstenberger (1862–1930), landowner and Duma member of the 2nd Duma (February – June 1907)

- Daniel Erdmann (1866–1942), Mayor and Romanian Member of Parliament

- Immanuel Wagner (1870–1946), mayor and founder of the cultural history museum of the German colonists of Bessarabia in Sarata

- Daniel Haase (1877–1939), senior pastor of the Protestant Church and Romanian member of parliament

- Immanuel Winkler (1886–1932), pastor of Bessarabia German origin and politician of the Black Sea Germans

- Karl Schmidt (around 1900), Mayor of Kischnew , merits in urban development and clarification of the Jewish pogrom of 1903

- Karl Rüb (1896–1970), founder of the relief organization for Bessarabia and Dobruja Germans in the Federal Republic

- Karl Stumpp (1896–1982), researcher of German abroad in Russia and Bessarabia

- Otto Broneske (1899–1989), chairman of the German People's Council for Bessarabia , later Gauleiter for Bessarabia and chairman of the Bessarabian German compatriot

- Immanuel Baumann (1900–1974), senior pastor of the Protestant Church

- Christian Fieß (1910–2001), founder of the local history museum of the Bessarabian Germans

- Hugo Schreiber (1919–2007), lawyer and editor of the bulletin of the Bessarabien Germans

- Edwin Kelm (* 1928), chairman of the Bessarabian German Landsmannschaft

- Arnulf Baumann (* 1932), pastor and federal chairman of the auxiliary committee of the Evangelical Lutheran Church from Bessarabia

- Viktor Dulger (1935–2016), engineer, inventor, entrepreneur and important patron of art and science

- Heinrich Fink (1935–2020), theologian, unofficial employee (IM) of the MfS and chairman of the VVN-BdA

- Horst Köhler (* 1943), child of Bessarabian German parents and former German President

- Ute Schmidt (* 1943), historian

Priest Ignaz Lindl

Pastor Arnulf Baumann

Relationship to other nationalities and German ethnic groups

Bessarabia has always been a multicultural area that has always been a transit area for many peoples. The area was inhabited by a variety of nationalities, among which the Romanians ( Moldovans ) were the majority. After the Russians, Ukrainians, Jews and Bulgarians, the Germans in Bessarabia were the fifth largest minority according to the Romanian census of 1930, with a population of only three percent. Other minorities were the Gagauz , Gypsies ( Roma ), Armenians , Greeks and Albanians . Mixing of the population groups was rare, the coexistence presented itself as parallelism. It was mostly peaceful and in good neighborhood in a coexistence and coexistence over generations. Compared to the other population groups, the Germans had an economic advantage because of their typically German virtues ( hard work , orderliness, thrift). Respect for their reliability was expressed by the fact that business was done with the proverbial German word .

The German colonists mostly inhabited their own villages, as did the other peoples in Bessarabia. In mixed villages, the Germans clung to their national identity. The demarcation had no National Socialist (as it did not yet exist) causes or racist feelings of superiority. The decisive reason was the different religious affiliation. Since church and religion were identity-creating moments for the Bessarabian Germans abroad, there were hardly any mixed marriages. Nevertheless, the different ethnic groups lived side by side in peaceful cooperation. The Bessarabian Germans often employed Moldovans, Russians or Bulgarians as farm laborers on their farms. The Germans demanded as hard work from their assistants as they did themselves, but they paid and fed well.

Surrounding German ethnic groups were the Bukowina Germans in the northwest , the Transylvanian Saxons in the west , the Dobrudscha Germans in the south from the mouth of the Danube and the Black Sea Germans in the east from Odessa . There were no closer ties between the ethnic groups (apart from the joint representation by the German party in Romania during the interwar period ), but there was a certain fluctuation towards the south due to relocations in search of new land.

Language and dialect

In the Tsarist period until 1918, the Bessarabian Germans learned the Russian state language. After the transition from Bessarabia to Romania in 1918, Romanian had to be learned as the new state language. But one always stayed true to the German mother tongue . However, numerous foreign words crept into the vocabulary that were borrowed from the ethnic mix of Romanian, Ukrainian, Russian, Bulgarian and Gagauz components that lived there.

There were two different dialects within the German colonists, based on their different origins from Germany. The speakers were assigned to either the Swabians or the Kashubians . The colonists who emigrated from southern Germany were considered Swabians . Their dialects, the South Franconian and the Swabian , were most strongly represented. But the less common Kashubian Low German dialect was also retained. Kashubian had nothing in common with the Slavic Kashubian tribe from the Danzig area. In Bessarabia, Kashubs was a derisive name for the Warsaw colonists who had immigrated from the Grand Duchy of Warsaw . They had kept their East Pomeranian dialect .

End of colonist privileges and renewed emigration

Since immigration, the settlers had the privileged status of colonists under the leadership of the Welfare Committee for the Colonists of Southern Russia . In 1871 the privileges that had once been promised for ever were withdrawn. It was believed that the colonists no longer needed support because of their good economic situation. The introduction of the 15-year (six active, nine reservist years ) military service from 1874 and the scarcity of land suddenly led to an emigration of an estimated 25,000 people, especially to North America , Brazil and Argentina . Despite this emigration from Bessarabia, the German population had grown from 9,000 immigrants to around 93,000 within 125 years by 1940.

Russification

From 1880 the Russification intensified in the course of the emerging Pan-Slavism . At the beginning of the 20th century, many Bessarabian and Black Sea Germans went to the University of Dorpat , primarily to study Protestant theology . In February 1908 they founded the southerners' association Teutonia . The members included Otto Broneske, Georg Leibbrandt and Karl Stumpp.

All minorities in the Tsarist Empire were affected by the consequences of Russification, especially Jews through pogroms . The Bessarabian Germans were accused of a lack of assimilation. The climax were planned expropriations and deportations at the beginning of the First World War in 1915 as well as the closure of German schools. When Bessarabia secluded itself from the Russian Empire in the October Revolution in 1917 , the repression ended.

Romanian interlude

Bessarabia's connection to Romania

The Bessarabian Germans had been subjects of the Russian tsar for over 100 years since they emigrated from the states of the German Confederation . Between 1918 and 1940 they became Romanian citizens for 22 years. This was a consequence of the Russian October Revolution in 1917, when Bessarabia also began to strive for independence. Under the name "Landesrat" ( Sfatul Țării ), a national people's assembly was formed in the Bessarabian capital Chișinău (Russian: Kishinew), which took over the government. The Provincial Council declared annexation to Romania in 1918, probably because of the Romanian majority in the population. The Bessarabian Germans thus escaped the fate of the other Russian Germans and the neighboring Black Sea Germans in the Soviet Union, which consisted of social disadvantage up to deportation or forced labor. In return, the Romanian state partially restricted the cultural autonomy of the Bessarabian Germans (like all minorities). Only Romanian was allowed to be spoken in public .

National Socialist Aspirations

At the beginning of the 20th century, after almost 100 years abroad, contact with motherland Germany was completely broken. Like many other ethnic groups in the newly formed Greater Romania after 1918, the Bessarabian Germans remained a national minority. Politically, they were organized in the German People's Council for Bessarabia , which is considered conservative and ecclesiastical . Its representatives were dignitaries from church and business.

With the seizure of power of Hitler in 1933 attacked Nazi ideas on the 1,500 km away Bessarabia increasingly over. Most of the rural, ecclesiastical Bessarabian Germans remained politically disinterested or even negative about developments in Germany. The breeding grounds for the success of the Nazi ideas were:

- idealized image of Germany

- Discrimination against minorities through Romanization policy

- Revolt of youth and intellectuals against the conservative and church-oriented leadership group

The emerging National Socialism among the Bessarabian Germans was fed by the sources:

- From Transylvania , which, like Bessarabia, was part of Romania, the influence came from the National Socialist Self-Help Movement of the Germans in Romania (NSDR) and, after it was banned in 1933, from the successor organization National Renewal Movement of Germans in Romania (NEDR), which broke up in 1934 because of internal power struggles dissolved. The supporters organized themselves in the German party in Romania , which was temporarily chaired by the National Socialist Fritz Fabritius .

- The Bessarabian youth movement, which was originally influenced by the German Wandervogel movement, gradually adapted outwardly to the Hitler Youth . Festive gatherings were held with NS-like appearance through emblems, costumes and honors. Artur Fink from Tarutino was the initiator of the youth movement . He organized a more sporty youth work with field games, but also with paramilitary marches. There were also increased visits to the motherland Germany. The ideology in Nazi sense took place at training in the Transylvanian Sibiu .

- In 1933 the Bessarabian German Renewal Movement was formed in Tarutino . It included intellectuals (teachers, church leaders) as non-peasant professions. It aimed for a völkisch revival , idealized Germany and was anti-communist oriented. The group soon disbanded and joined the Transylvanian National Renewal Movement of Germans in Romania (NEDR). After its dissolution in 1935, National Socialist ideas continued to exist among representatives of the ethnic group, but wing battles for power and political orientation continued for years. The more radical wing of the renewal movement adopted Nazi ideologies from Germany, including the Führer principle . The moderate wing did not consider it appropriate to represent the National Socialist race and blood-and-soil doctrine abroad. He strove for the political equality of the German minority in the Romanian mother country.

"Back home"

To secure the attack on Poland , the German Reich concluded the German-Soviet non-aggression pact in August 1939 and the German-Soviet border and friendship treaty in September to partition Poland . So-called areas of interest between Germany and the Soviet Union were defined in confidential parts (Bessarabia was in the Soviet Union) and, in order to prevent nationality conflicts, the resettlement of German and Soviet minorities was agreed on a voluntary basis. In October 1939, Hitler appointed Heinrich Himmler Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Volkstum and entrusted him with the ethnic reorganization (Germanization) of Poland. For this purpose, the expulsion of Poles and Jews from the new eastern regions of the empire were organized in so-called local plans, whose land and property were used for the settlement of racially impeccable ethnic Germans but also Germans from the old empire. With the slogan "Heim ins Reich", the ethnic resettlement experts put the alleged securing of the survival of German minorities in the foreground. In fact, the National Socialist population planners wanted additional human reserves and manpower potentials for their long-term policies of conquest, expulsion, population and extermination to obtain.

Soviet occupation summer 1940

After the end of the German campaign in the west with the signing of the Armistice at Compiègne on June 22, 1940, the Soviet Union saw the time to demand the return of the former Russian territories of Bessarabia from Romania. With the military defeat of France, Romania had lost its ally. On June 28, 1940, the Soviet Red Army surprisingly occupied the territory of Bessarabia. Romania had previously received a 48-hour ultimatum for assignment. Romania mobilized, but did not take up the fight because the German government recommended giving in to Soviet demands. As agreed in the secret additional protocol of the 1939 Hitler-Stalin Pact , the German Reich tolerated the occupation. In relation to the Soviet Union it expressed its disinterest in the Bessarabian question , but not in the fate of the 94,000 or so members of the German-speaking minority living there. It called for the resettlement of the German population in accordance with the 1939 German-Soviet border and friendship treaty in the German Reich. On September 5, 1940, the Soviet Union and the German Reich signed a resettlement agreement in Moscow . He made it possible for all Bessarabian Germans to resettle in Germany. Every resident aged 14 and over could make the decision themselves. Propagated reasons to consent to the resettlement and even to see it as a rescue measure were:

- Fear of lawlessness ( deportation )

- Giving up one's own soil ( forced collectivization )

- End of German cultural and church life

- Beginning impoverishment in Bessarabia even before the occupation

- Hope for a materially better life in the German Reich

- "Völkische Duty" to "return" to the "motherland"

Between totalitarian regimes

The resettlement was in fact a withdrawal from 125-year-old settlement areas of German eastern settlers. Under the motto Heim ins Reich , the Nazi regime exploited resettlement for its propaganda purposes. The loss of homeland suffered by 93,000 people when they returned to the Reich was actually reversed. Quote:

- “He happily leaves” (the Bessarabian German farmer) “house and farm and returns home to the Reich with few belongings. His most ardent wish for many years to be able to return to his homeland in Germany has now become a fact. "

An SS man involved in the resettlement sketched his emigrated compatriots in Nazi propaganda style as follows:

- “The Bessarabian farmer can be described as good from a national and partly racial point of view. He has remained true to the customs and traditions as well as the language and dialect of his fathers for a century. "

The decision to leave the Bessarabian Germans in the autumn of 1940 was largely due to the measures taken by the new Soviet rulers, such as:

- Delivery of a harvest target

- Closure of German schools

- Confiscation of hospitals and pharmacies

- Expropriation of banks and industrial companies

- Arrest of landowners and members of other ethnic groups

According to Soviet sources, the measures in the occupied area served the purpose of Sovietization and the fight against counter-revolutionary activities. They continued even after the Germans left. At the end of 1940 the abandoned lands were assigned to newly established sovkhozes and collective farms . In 1941 around 30,000 residents of Bessarabia were deported to Siberia as "anti-Soviet elements" in gulags .

Relocation in autumn 1940

Almost all of a sudden, the 93,000-strong German ethnic group decided to resettle in September 1940 and left their 150 or so Bessarabian German settlements . Only about 1000 Germans remained (mostly because of spouses of different ethnic origins or of old age). The practical implementation was carried out by the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle (VoMi), an SS organization . 600 uniformed SS men (without badges) were sent to Bessarabia. They registered those wishing to resettle in the local schools. For subsequent compensation valued appraisers in a Soviet-German resettlement commission the value of the remaining property, such as land with buildings and inventory, livestock, harvest. Due to differing views on the concept of personal property, there were considerable differences of opinion about assets.

Between October 2 and 25, 1940, most of the Bessarabian Germans left with 30 kg of luggage per person. Women and children were transported by truck to the ports of the Danube Reni , Kilija and Galați (Galatz), which are up to 150 km away , where they were accommodated in assembly camps. The men followed there as a trek with covered wagons . After a short stop, the Danube fleet's excursion steamers set off 1000 km up the Danube towards Germany. The ships' destination was Prahovo and Semlin near Belgrade , where transit camps were set up. From there, after a short stay, the resettlers traveled by train to the German Reich. Many ethnic Germans living in what was then Yugoslavia had volunteered to help.

A number of disabled and sick people as well as the residents of the Alexander Asylum Compassionate Center in Sarata were transported in separate transports to state institutions in the German Reich and perished there in killing campaigns ( murders of the sick during the Nazi era ).

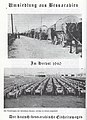

Transport from Klöstitz

Camp stay and naturalization

After their arrival in the Reich at the end of 1940 , the Bessarabian Germans were housed in around 250 resettlement camps in Saxony , Franconia , Bavaria , in the Sudetenland and in Austria . They lived cramped for a year or two in schools, gyms or ballrooms in inns.

As with all returnees, the native German population was initially aloof from the Bessarabian Germans because of their strange customs and traditions. Because of their region of origin, Bessarabia , they were initially mistaken for Arabs and derisively referred to as Better Arabs . Because of brought from their homeland, black Karakulmützen they were called also bobble hats .

Already in the early days of their return, men capable of military service were called up for military service. Men escaped the stay in the camp by volunteering for the SS . There was a need there because of their trilingualism (German, Romanian, Russian), which enabled them to work as an interpreter on the Eastern Front in the pursuit of partisans , Jews and commissioners of the Red Army . The Waffen-SS found welcome recruits among the Bessarabian Germans as well as among other Romanian citizens of German origin .

During the stay in the camp, the ethnic Germans had to undergo a naturalization procedure. This included a health and racial-political investigation. Only those who were classified as healthy, racially valuable and politically reliable could settle as a free farmer on their own soil in the eastern Polish territories conquered by Hitler's Germany ( O cases ) or as a recruit in the Waffen SS.

Around 12,000 Bessarabian Germans were not considered worth settling in the East for various reasons (health, racial, political) and had to hire themselves out as workers in the Old Reich ( A cases ). Farmers who had previously managed farms with 30 hectares or more should not be given land in the east to settle because of their Baltic cheekbones, chest hair or illnesses in the family, as a blonde province was to be created there according to Himmler's maxim . That was an open breach of the promise to reunite the national community and to resettle it with adequate compensation for its property left behind.

Resettlement in occupied Poland

In 1941/42, the Bessarabian Germans were resettled in occupied Poland , especially in Wartheland , in Danzig-West Prussia and, to a lesser extent, in the General Government. This happened within the framework of the General Plan Ost , a National Socialist settlement project for Germanization . The German occupying power confiscated the property and farms of Polish residents. The property was cleared by the German military through the use of force or threats of violence. Immediately afterwards (quote: "Sometimes the beds were still warm") Bessarabian German families were brought to the farms, which they received as (temporary) compensation for their abandoned property in Bessarabia. The former Polish owners often served as servants on the farms . Many of the Bessarabian Germans, who sprang from a strict ecclesiastical tradition, saw the injustice in their new beginning in the German Empire. Nevertheless, they accepted the assigned farms and dared to start over as independent farmers after the bitter time of inactivity and crampedness during their one to two year stay in the camp.

Bessarabian Germans were also settled in the General Government near the Russian border as part of Aktion Zamość . This led to partisan attacks at night in which many new settlers lost their lives. Probably emerging from the expelled farm owners, partisans took back their share. Even the SS-Landwacht Zamosc , a self-protection organization from the ranks of German-born new settlers under the leadership of the SS, could not stop the attacks.

Escape to the west

When the Red Army and with it the front drew closer in 1944/45 , the German settlement and Germanization project in the east failed after only two years. The Bessarabian Germans, like the rest of the resident German population, fled in refugee treks to the west into the area of the later Federal Republic of Germany and the later German Democratic Republic. Many were overrun by the approaching front and remained, in some cases for years, in Polish territories until they were expelled to Germany.

Bessarabian Germans in Germany

integration

In post-war Germany, of the around 93,000 people resettled from Bessarabia after the Second World War, around 80,000 had arrived in Germany. Around 2,200 members of the ethnic group perished in the war. In the immediate post-war period , around 50,000 people lived in the south of the Federal Republic of Germany , around 20,000 people in the north of the Federal Republic and around 10,000 people in the area of the German Democratic Republic . A statistical analysis of the home town index in 1964 showed that around 79,000 people were still alive, around 65,000 of them in the Federal Republic and around 12,000 in the GDR.

As newcomers, the Bessarabian Germans, like the rest of the expellees from the eastern German territories , faced an enormous integration effort. As a peasant people, most of the members of this ethnic group only knew about agriculture. When they arrived in Germany as dispossessed refugees, very few succeeded in making a new start as independent farmers. Most of the Bessarabian Germans turned away from agriculture professionally after 1945 and became industrial workers in both West and East Germany. Since they had left their property in Bessarabia in 1940 and had not received any compensation during the Third Reich, those living in the Federal Republic took part in the burden sharing from 1952 . That offered a partial financial replacement. A large part of the ethnic group settled in Baden-Württemberg , from where their ancestors once emigrated. The integration of the Bessarabian Germans into German society proceeded quickly in the same way as with other expellees and was completed in the first post-war years.

In an effort to be able to continue to practice agriculture, plans to emigrate came up within the Bessarabian Germans in West Germany in the 1950s. They wanted to emigrate in large numbers to Paraguay in South America . The plans could not be implemented for financial reasons.

Organizing

While associations of expellees and local associations were banned in the GDR for political reasons, after the Second World War Bessarabian Germans created the following organizations in the Federal Republic:

- Country team of the Bessarabian Germans

- Local history museum of the Bessarabian Germans

- Auxiliary Committee of the Evangelical Lutheran Church from Bessarabia

- Alexander-Stift (Diaconal geriatric care facility)

In 1960, the Landsmannschaft in Stuttgart built the home of the Bessarabian Germans . The Stuttgart location was chosen because the city had been sponsored since 1954. Another reason was the origin of most of the members of the ethnic group from what is now Baden-Württemberg before they emigrated at the beginning of the 19th century.

In 2006 the individual organizations merged to form the Bessarabiendeutscher Verein , but the Alexanderstift geriatric care facility became independent for economic reasons.

Pietist circles formed in the post-war period in the Bessarabic Community Association , also known as the Bessarabic Prayer Society . In 1974 the name was changed to Evangelical Community Association North-South .

Maintenance of tradition

Today the Bessarabiendeutsche Verein maintains the culture and tradition of the Bessarabiendeutsche. A newsletter appears monthly , and a home calendar every year .

Home meetings or anniversary events on the occasion of the founding of villages (numerous 190-year celebrations in 2004/05) take place regularly. Regular venues are Stuttgart and Bad Sachsa. Cooking courses are also offered to pass on the Bessarabian German cuisine. The events and the number of participants have increased since around 2005, although most of the experience generation of the settlement area abandoned in 1940 is no longer alive. The two-verse Heimatlied of the Bessarabian Germans , which Albert Mauch wrote in 1922, is often sung at the meetings . It is a connecting piece of music.

Since 2010 there has been a traveling exhibition under the motto Pious and Able People ... The German Settlements in Bessarabia 1814–1940 , which shows the history of the German colonists from the settlement in Bessarabia in 1814 until today. Previous and future positions were or are Chișinău , Comrat , Cahul , Tarutino , Odessa , Munich , Bilhorod-Dnistrowskyj , Minneapolis , Bismarck , Stuttgart , Chernivtsi , Hanover , Ismail, Ulm , Balti and Bonn . The exhibition was initiated by the historian Ute Schmidt and the visual artist Ulrich Baehr from the University of Hanover .

Today's contacts to the old homeland

Since the former Bessarabia belonged to the Soviet Union after 1945, contacts and visits to the old homeland were initially not possible from the Federal Republic . Individual trips from the GDR were possible due to membership of the Eastern Bloc, but only took place in a few individual cases. At the end of the 1960s there were first study trips to the region from Germany. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Bessarabian Germans have cultivated diverse contacts in the former Bessarabia, which became part of Ukraine and Moldova. The freedom to travel enables a number of organized “home trips” to be carried out every year. There is hardly any further tourism to the former Bessarabia due to the lack of destinations and gastronomy.

Due to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the population became extremely poor. The chairman of the Homeland Association of Bessarabian Germans Edwin Kelm called in 1991/92 in Germany diaconal institution Bessarabia aid to life. It carried out aid deliveries by truck for the people living in the former Bessarabia. Humanitarian aid items such as medicines, medical equipment and clothing came into the country through donations. Initially, the aid reached hospitals, old people's homes and orphanages in Akkerman, Arzis, Kischinew, Schabo and Tarutino. Goods later came to the formerly German communities and to other people in need. Around 70,000 aid packages were handed out. Schools were also provided with teaching and learning materials. Edwin Kelm personally ensured that the hospital in Schabo in the Ukraine, a former wine-growing settlement of Swiss emigrants, was improved .

Bessarabian Germans set up memorial stones in many of their home villages. To date (2010) there are bilingual memorial stones in around 50 settlements (from around 150 previously). There are memorial stones in all 24 mother communities. They are reminiscent of the places' earlier German past. The Bessarabian German Edwin Kelm planned and supervised the restoration of the oldest German church in Bessarabia in Sarata, which was inaugurated again in 1995. He was also involved in the construction of a new church in Bilhorod-Dnistrowskyj and the reconstruction of the German church in Albota (Moldova). In the 1990s, Edwin Kelm bought his grandparents' former farm in Friedenstal . He redesigned it into the farmer's museum, which opened in 1998 and donated it to the Bessarabiendeutsche Verein in 2009.

See also

Places and regions:

Other German-speaking minorities :

literature

- Immanuel Wagner: On the history of the Germans in Bessarabia . Local museum of the Germans in Bessarabia. Melter, Mühlacker 1958, (2nd edition, unchanged photomechanical reprint: Heimatmuseum der Deutschen in Bessarabien, Mühlacker 1982, ( Heimatmuseum der Deutschen von Bessarabien, series A 1, ZDB -ID 1333223-5 ), (reproduction Christian Fiess, ed.)) .

- Alois Leinz: Homeland book of the Bessarabian Germans - 20 years after the resettlement . Published on behalf of the Bessarabiendeutschen Landsmannschaft Rhineland-Palatinate. Wester, Andernach 1960.

- Alfred Cammann : On the people of the Germans from Bessarabia . Holzner Würzburg 1962, ( Göttinger Arbeitskreis Schriftenreihe 66, ZDB -ID 846807-2 ), ( Göttinger Arbeitskreis Publication 259).

- Friedrich Fiechtner: Home in the steppe . Selected and edited from the literature of the Bessarabian Germans. Association for the Promotion of the Literature of the Germans from Bessarabia, Stuttgart 1964, ( publications of the Association for the Promotion of the Literature of the Germans from Bessarabia 1, ZDB -ID 984243-3 ).

- Albert Kern (Hrsg.): Heimatbuch der Bessarabiendeutschen . Aid committee of the Evangelical Lutheran Church from Bessarabia, Hanover 1964.

- Jakob Becker: Bessarabia and its Germanness . Krug, Bietigheim 1966.

- Dirk Jachomowski: The resettlement of the Bessarabia, Bukovina and Dobruja Germans. From the ethnic group in Romania to the “settlement bridge” on the imperial border . Oldenbourg, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-486-52471-2 , ( Book series of the Southeast German Historical Commission 32), (At the same time: Kiel, Univ., Diss., 1984).

- Arnulf Baumann : The Germans from Bessarabia. Auxiliary Committee of the Evangelical Lutheran Church from Bessarabia, Hanover 2000, ISBN 3-9807392-1-X .

- Ute Schmidt : The Germans from Bessarabia. A minority from Southeast Europe. (1814 until today) , Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-412-01406-0 online

- Andreas Siewert (Ed.): Bessarabia. Traces in the past. A picture documentation . Baier, Crailsheim 2005, ISBN 3-929233-44-4 .

- Cornelia Schlarb: Tradition in Transition. The Evangelical Lutheran congregations in Bessarabia 1814–1940 . Böhlau, Cologne a. a. 2007, ISBN 978-3-412-18206-9 , ( Studia Transylvanica 35). on-line

- Ute Schmidt: Bessarabia. German colonists on the Black Sea . German Cultural Forum Eastern Europe, Potsdam 2008, ISBN 978-3-936168-20-4 , ( Potsdam Library Eastern Europe - History ).

- Ute Schmidt: "Home to the Reich"? Propaganda and reality of the resettlements after the "Hitler-Stalin Pact" . Journal of the Research Association SED, ZdF 26/2009, pp. 43–60.

Web links

General

- The Bessarabian Germans

- Genealogical sources on the Bessarabian Germans

- Odessa Digital Library with genealogical research on the Bessarabian Germans (English)

- German photos from Bessarabia from the 1930s (English)

- Childhood memories of a Bessarabian German farm ( Memento from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Local clan books of Bessarabian German communities and families

- Bessarabia German picture calendar

- Website of a native German writer from Bessarabia

- Moldovarious.com - article about Bessarabia German (English)

- Traveling exhibition "Pious and able people" on the German settlements in Bessarabia 1814–1940

Settlements

- Map of former German settlements in Bessarabia (PDF, 411 kb, zoomable)

- Gnadenfeld - A German daughter colony in Bessarabia

- Hannowka - A German Village in Bessarabia 1896–1940

- Klöstitz, a place in Bessarabia

- Orbeljanowka , a colony founded by Bessarabian German Templars in the North Caucasus

- Sarata, a German mother colony in Bessarabia

- Sofiental - A German daughter colony in Bessarabia

- Scholtoi - a village in northern Bessarabia

- Schabo - a Swiss colony in Bessarabia

- Swiss viticulture in Schabo, from Lac Léman to “Lac Liman” (Neue Zürcher Zeitung, June 27, 2012)

Relocation

- The German-Soviet State Treaty on the Resettlement of Ethnic Germans from Bessarabia and North Bukovina ( Memento of March 14, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- Call for the resettlement of ethnic Germans from Bessarabia and North Bukovina ( Memento from March 14, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- Description of the resettlement from 1940

- Report by a member of the resettlement commission ( memento from August 25, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- Resettlement, settlement, flight, displacement

- Hitler-Stalin Pact. Flawless human material by Ute Schmidt in FAZ from August 2, 2009

- Resettlement, settlement, flight, eviction with historical documents and photos

Individual evidence

- ↑ Origin of the Bessarabian families: The Warsaw colonists

- ^ The German colonists in Bessarabia, Karl Wilhelm Kludt, Odessa, 1900

- ↑ Johannes Dölker: The colonist horse in the local calendar of the Bessarbien Germans , 1966

- ↑ Cooking recipes

- ^ Bessarabiendeutsche: Haus und Hof

- ↑ Lindls person and effectiveness in: The German colonists in Bessarabia, Karl Wilhelm Kludt, Odessa, 1900

- ^ Axel Hindemith: State of health of the Bessarabian Germans. In: Yearbook of Germans from Bessarabia 2005 ( Memento from December 19, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) based on: Otto Fischer: About the living conditions of Germans in Bessarabia with regard to future resettlement , Vienna 1939.

- ↑ Hans Wagner in: Heimatkalender der Bessarabiendeutschen 1956 and Axel Hindemith: Bessarabiens Wappen in Jahrbuch der Bessarabiendeutschen 2008 ( Memento from October 29, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Bessarabiendeutsche: Bessarabisches Heimatlied

- ↑ Harald Seewann : TEUTONIA Dorpat / Tübingen - a union of German colonist sons studying from Russia (1908–1933) . Einst und Jetzt , Volume 34 (1989), pp. 197-206.

- ^ Hugo Schreiber: The renewal movement in Bessarabia in: Yearbook of Germans from Bessarabia 2008 ( Memento from October 29, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Markus Leniger: National Socialist People's Work and Resettlement Policy 1933–1945. Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-86596-082-5 , pp. 87 ff.

- ↑ Ute Schmidt: "Heim ins Reich"? Propaganda and reality of the resettlements after the "Hitler-Stalin Pact". P. 59.

- ^ Http://www.kloestitzgenealogy.org : The resettlement agreement of September 5, 1940

- ↑ Markus Leniger: National Socialist People's Work and Resettlement Policy 1933–1945. Berlin 2006, p. 87.

- ^ A b Karl Heinz Feulner: Return of the ethnic German farmers. As an agricultural appraiser during the resettlement campaign in Bessarabia in Fränkischer Kurier on December 29, 1940.

- ↑ Heinrich Himmler's resettlement order of October 12, 1939 as "Order 21 / II" (PDF file; 14 kB)

- ^ Resettlement in 1940

- ^ Rolf-Dieter Müller: On the side of the Wehrmacht: Hitler's foreign helpers in the "Crusade against Bolshevism" 1941–1945. Fischer TB, Frankfurt 2010, ISBN 978-3-596-18150-6 , p. 56.

- ↑ Ute Schmidt: "Heim ins Reich"? Propaganda and reality of the resettlements after the "Hitler-Stalin Pact". P. 55.

- ↑ Presentation on the website

- ^ Christmas letter 2009 of the Bessarabiendeutsche Verein