Persian carpet

A Persian carpet ( Persian قالی qālī ) is a heavy fabric made for a wide range of useful and symbolic purposes that is made in Iran , Afghanistan, and the surrounding areas of the former Persian Empire . Persian carpets are produced for their own use, for local trade and for export. The Persian carpet is a basic component of Persian art and culture. Itis known colloquially in German-speaking countries as the Persian carpet . Within the group of oriental carpets , the Persian carpet stands out due to the special diversity and artistic quality of its colors and patterns. In 2010 the “traditional art of carpet-making” in Fars and Kashan was added to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity .

Persian carpets of various kinds were knotted at the same time by nomadic tribes, villages, urban and court manufacturers. This rough classification according to the social class for which carpets were made stands for different, simultaneously existing traditions, and reflects the long and rich history of Iran and the peoples who live there.

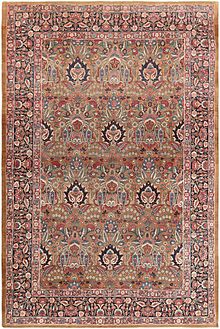

The carpets from the Safavid court manufactories in Isfahan in the 16th century are world famous for their diverse, rich colors and artistic patterns. The Safavid motifs and patterns influenced the court manufactories of the surrounding great powers of the Islamic world and were knotted again and again throughout the later Persian Empire up to the last imperial dynasty of Iran. In cities and market centers such as Tabriz , Kerman , Mashhad , Kashan, Isfahan, Nain and Ghom , carpets are made of high quality using different techniques and materials, colors and patterns. Nomads and residents of rural villages knot carpets with stronger and sometimes coarser patterns or highly simplified (almost diagram-like) figures, which are now regarded as the most authentic and traditional carpets in Iran.

During times of political unrest or under the influence of commercial production, the handicraft of carpet weaving went through periods of decline. The introduction of inferior synthetic paints in the second half of the 19th century proved to be particularly serious. Carpet weaving still plays an important role in the economic life of modern Iran. Modern production is characterized by the revival of the traditional art of dyeing with natural colors and traditional patterns, but also by the invention of modern, innovative patterns that are made in the centuries-old craft tradition. Hand-knotted Persian carpets have been valued all over the world as objects of high artistic and practical value and prestige since their first mention in ancient Greek scriptures up to the present day.

history

Early history: around 500 BC Chr. - 200 AD

Persian carpets are first used around 400 BC. Mentioned by the Greek author Xenophon in his work Anabasis :

"αὖθις δὲ Τιμασίωνι τῷ Δαρδανεῖ προσελθών, ἐπεὶ ἤκουσεν αὐτῷ εἶναι καὶ ἐκπώματα καὶ τκπώματα καὶ τάπιδας (καρab.

- Then he went to Timasion the Dardanian, because he had heard that he had some foreign drinking vessels and carpets.

"καὶ Τιμασίων προπίνων ἐδωρήσατο φιάλην τε ἀργυρᾶν καὶ τάπιδα ἀξίαν δέκα μνῶν." [Xenophon, Anabasis VII, 3.27]

- Timasion also drank to his health and gave him a silver goblet and a rug that was worth 10 mines.

Xenophon describes Persian ("foreign") carpets as precious and worth a diplomatic gift. It is not known whether these carpets were knotted or made using some other technique, e.g. flat weave or embroidery , but it seems interesting that the first mention of Persian carpets in world literature puts them in a context of luxury, Prestige, and diplomacy represents.

From the time of the Achaemenids (553–330 BC), Seleucids (312–129 BC), and Parthians (approx. 170 BC - 226 AD), no carpets have survived.

Sassanid Period: 224–651

The Sassanid Empire , which replaced the Parthian Empire , was one of the leading powers of its time alongside neighboring Byzantium for over 400 years . The Sassanids established their rule roughly within the boundaries already set by the Achaemenids. Their capital was Ctesiphon . This last Persian dynasty before the arrival of Islam followed Zoroastrianism as the state religion.

When and how exactly the Persians began to knot carpets is still unknown, but the knowledge of their manufacture and the knowledge of suitable designs for textile floor coverings was certainly known in the area comprising Byzantium, Anatolia and Persia for a long time. Anatolia , located between Byzantium and Persia, had been around since 133 BC. Under Roman rule. Geographically and politically, in changing alliances as well as through trade, Anatolia linked the Byzantine with the Persian Empire . In the artistic field, both empires developed similar styles and decorative vocabulary, as can be seen from mosaics and the architecture of Roman Antioch . A Turkish carpet pattern, depicted in Jan van Eyck's painting Virgin and Child by Canon van der Paele , could be traced back to late Roman origins and associated with Umayyad floor mosaics from Khirbat al-Mafdschar . The architectural elements in the building complex of Khirbat al-Mafjar are seen as exemplary for the appropriation and further development of pre-Islamic patterns in early Islamic art (Broug, 2013, p. 7.).

Flat weaving and embroidery were known during the Sassanid period. Finely crafted Sassanid silk fabrics have survived in European churches, where they were often used to wrap relics in them. More textiles of this type were preserved in Tibetan monasteries, from where they were taken by monks who fled to Nepal from the Chinese Cultural Revolution . Similar finds have also been preserved from burial sites such as in Nur-Sultan (Astana until 2019) , located on the Silk Road near Turfan . The high artistic level of the Persian weavers emerges from the reports of the Arab historian at-Tabarī about the Bahār-e Kisra , or "Spring of the Ḵosrow" carpet ( Pers .: فرش بهارستان , spring carpet ), which was used as spoils of war by the Arab conquerors of Ctesiphon fell into the hands of AD 637. The description given by at-Tabarī of the carpet makes it rather unlikely that this carpet had a knotted pile.

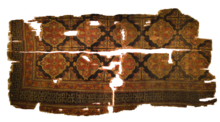

Fragments of knotted carpets from sites in northeast Afghanistan , probably from Samangan Province , were dated using the radiocarbon method to the period between the end of the second century and the early Sassanid period. Some of these fragments show images of animals such as various deer (sometimes lined up in processions like on the Pazyryk carpet ), or various winged mythical animals. The warp, weft and pile are made of coarsely spun wool. The fragments are tied with asymmetrical knots, as in later Persian and Far Eastern carpets. Every three to five rows of wefts, strands of unspun wool and strips of fabric and leather are woven in. These fragments are now kept in the Al-Sabah Collection in the House of Islamic Art (Dar al-Athar al-Islamyya), Kuwait .

The carpet fragments, although they can be reliably dated to the early Sassanid period, seem to have no relation to the magnificent court carpets that describe the Arab conquerors. Their coarse weave and the incorporation of pile on the side facing the floor rather suggest that these fabrics served better insulation against the cold of the floor. In view of their roughly drawn depictions of animals and hunting, it is more likely that these carpets were made by and for nomads.

Expansion of Islam and rule of the caliphs: 651–1258

The Arab conquest of Persia in 651 led to the end of the Sassanid Empire and the decline of the Zoroastrian religion in Persia. Persia became part of the Islamic world and was ruled by caliphs .

Arab geographers and historians who traveled through Persia also report for the first time that carpets were used as floor coverings. The unknown author of the Hudūd al-ʿĀlam reports that carpets were knotted in Fārs. 100 years later, al-Muqaddasi reports on carpets from the Qaināt. Yāqūt ar-Rūmī mentions carpets from Azerbaijan in the 13th century . The great Arab traveler Ibn Battuta reports that a green carpet was spread in front of him when he visited the winter residence of the Bakhthiar Atabeg in Izeh . The reports suggest that carpets were made by nomadic tribes or in rural workshops during the Caliphate in Persia.

The rule of the caliphs over Persia ended after the Abbasid caliphate was defeated by the Mongol empire under Hulegü with the conquest of Baghdad (1258) . The Abbasids withdrew to the Mamluk Sultanate of Cairo . The Mamluk Sultan Baibars installed the Abbasid al-Mustansir II as the next caliph in 1261. Although without political influence, the dynasty was able to maintain its religious authority until the conquest of Egypt by the Ottoman Empire in 1517 . Under the Mamluk dynasty, large-format carpets were made in Cairo, known as "Mamluk carpets".

Invasion of the Seljuks and Turkic-Persian tradition: 1040–1118

With the invasion of Anatolia and northwestern Persia by the Seljuks , a separate Turkish-Persian tradition developed. Fragments of knotted carpets were found in the Alâeddin Mosque in the Turkish city of Konya and the Eşrefoğlu Mosque in Beyşehir , and dated to the time of the Sultanate of the Rum Seljuks (1243–1302). Other carpet fragments were found in Fustāt . These fragments give an idea of what Seljuk carpets might have looked like. The finds from Egypt also prove that export trade was already being carried out at this time. Whether and how these carpets influenced Persian production is still unknown, because no clearly Persian carpets exist from this period or we cannot identify them as such. It is believed that the Seljuks introduced at least new patterns to Persia, if not the craft of carpet-knotting itself.

Mongolian Ilkhanate (1256–1335) and Timurid Empire (1370–1507)

Persia was invaded by the Mongols between 1219 and 1221 . After 1260 the descendants of Hülagü Chan carried the title " Ilchane ". Towards the end of the 13th century, Ghazan Ilchan built a new capital in Shãm, near Tabriz . He ordered that the floors of his residence be covered with carpets from Fārs.

With the death of Ilchan Abu Said Bahatur in 1335, the Mongol rule in Persia collapsed and the country fell into political anarchy. In 1381 Timur invaded Persia and founded the Timurid Empire . His successors retained the rule over a large part of Persia until they were subject to the alliance of the Aq Qoyunlu under Uzun Hasan in 1468 ; Uzun Hasan and his descendants ruled Persia until the rise of the Safavids.

In 1463 the Senate of Venice , looking for allies in the Ottoman-Venetian War, entered into diplomatic relations with the court of Uzun Hasan in Tabriz. In 1473 Giosafat Barbaro was sent to Tabriz as an ambassador. In his reports to the Venetian Senate, he mentions the splendid carpets that he saw in the palace several times. Some of them, he writes, were made of silk.

1403-1405 was Ruy González de Clavijo ambassador of King Henry III. of Castile at the court of Timur. He reports that in Timur's palace in Samarkand , “the floor was covered with carpets and reed mats everywhere.” Miniatures from the Timurid period show carpets with geometric patterns, rows of octagons and stars, knot ornaments and borders that sometimes resemble Kufic script. No carpets from Persian manufacture are known from the period before 1500.

Safavid Period: 1501–1732

In 1499 a new dynasty came to power. Its founder, Shah Ismail I , was a relative of Uzun Hasan. He is regarded as the first national ruler of Persia since the Arab expansion and established Shiite Islam as the state religion of Persia. Ismail I and his successors, Shah Tahmasp I and Shah Abbas I became important patrons of Safavid art. Court manufactories were probably set up by Shah Tahmasp in Tabriz, but certainly by Shah Abbas when he moved his capital from Tabriz in the northwest to Isfahan in central Persia during the Ottoman-Safavid War (1603-18) . For the art of carpet-knotting in Persia, this meant, as AC Edwards wrote: "That it rose from village level to the dignity of a high art in a short time".

The Safavid period is one of the highlights of Persian art, including carpet knotting. Carpets from the late Safavid period have been preserved and are among the finest and best-made knots that we know today. The phenomenon that the first completely preserved Persian carpets are of such perfect design assumes that carpet knotting as a handicraft must have been known for some time. Since no carpets from the Timurid period have survived, research has focused on book illustrations and miniatures from this period. The paintings depict carpets with colorful patterns made up of geometric ornaments of the same size, often arranged in cassette form and with "kufic" borders that come from Islamic calligraphy . The patterns are so similar to Anatolian carpets, especially the " Holbein carpets ", that a common origin is likely: Timurid patterns may have survived in both Persian and Anatolian carpets from the early Safavid and Ottoman times.

Early Safavid coffered carpets

A small group of preserved early Saafavid carpets is very similar to the painted carpets of the Timurid miniatures. The field of these carpets is divided into different, symmetrically arranged areas, which is why these carpets are called "coffered carpets". Preserved pieces are kept in the Metropolitan Museum of Art , New York, and in the Musée des Tissus , Lyon, a fragment is in the Museum of Islamic Art , Berlin. The field pattern mostly consists of eight-pass rosettes, which are surrounded by shield-shaped fields, filling motifs are dragon and phoenix pairs, cloud bands, arabesque tendrils and elongated cartouches. Some carpets have a medallion placed on the cassette field, these can be seen as a transition to the later medallion carpets. Tabriz is the place of manufacture .

"Model Revolution" and Dating

In the late 15th century, the patterns depicted in the miniatures changed fundamentally. Large-format medallions appear, the ornaments begin to flow in a curvilinear manner. Large spirals and tendrils, floral ornaments, images of flowers and animals often appear mirrored along the long or short axis of the carpet field and thus create harmony and rhythm. The older “ kufic ” border design is being replaced by tendrils and arabesques . All of these patterns required more sophisticated knotting techniques than those required for the straight, rectilinear patterns. Such a carpet cannot be knotted from memory, but needs artists to invent the pattern design, skilled weavers who execute the design on the loom, and a way to convey the artist's ideas to the weaver in an efficient way. Today this is made possible by templates (“cardboard boxes”). How the Safavid manufactories dealt with it is unknown. The result of their work, however, was the fundamental change in the pattern that was knotted, for which Kurt Erdmann coined the term "pattern revolution".

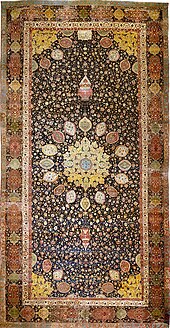

Apparently the new patterns were developed by miniature painters, for they first appear on book illuminations and book covers from the early 15th century. At this time, the pattern was established that was characteristic of the “classic” design of Islamic carpets: the medallion-and-corner design (pers .: Lechek Torūnj). In 1522, Ismail I hired the famous miniature painter of the Herat school, Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād, as head of the royal studio. Behzād had a decisive influence on the later development of Safavid art. The Safavid carpets known to us differ from the images in the miniatures, so that the book illustrations do not offer any help in classifying and dating the carpets known to us. Unfortunately, the same applies to European paintings, because in contrast to the Anatolian carpets that are well documented here, no Persian carpets are depicted on European paintings before the 17th century. Since a few carpets, such as the Ardabil carpets, have knotted inscriptions with the date, scientific attempts at classification and dating are based on these pieces.

“I know of no other refuge in this world than your threshold.

There is no protection for my head but this door.

The work of the Maqsud Threshold slave from Kashan in 946. "

The AH year 946 corresponds to AD 1539-40, so that the Ardabil carpet can be dated to the reign of Shah Tahmasp, who donated the carpets for the tomb of Sheikh Safi ad-Din Ardabilis in Ardabil , the spiritual father of the Safavid dynasty.

Another inscription can be identified on the hunting carpet, today in the Museo Poldi Pezzoli , Milan, and dates this carpet to the year 949 AH / AD 1542–3:

“Through the care of Ghyath ud-Din Jami,

this famous work that touches us with its beauty was accomplished .

In the year 949 "

The sources for a more precise dating and determination of origin flowed more abundantly during the 17th century. With the intensification of diplomatic exchanges, Safavid carpets came more often as gifts to European cities and states. In 1603, Shah Abbas I gave the Venetian Doge Marino Grimani a carpet with woven gold and silver threads. European aristocrats began ordering carpets directly from the Isfahan and Kashan factories , which were able to knot special patterns, such as European coats of arms, into the carpets. Occasionally the acquisition can be exactly traced: In 1601 the Armenian Sefer Muratowicz was bought by the Polish King Sigismund III. Wasa sent to Kashan to order eight carpets with the knotted coat of arms of the Polish ruling family. On September 12, 1602, Muratowicz was able to present the king with the carpets and his treasury with the invoice for carpets and travel expenses. It was mistakenly believed that representative Safavid carpets made of silk with interwoven silver and gold threads were knotted in Poland . Although the mistake was quickly cleared up, carpets of this type kept the generic name “Polish” or “Polonaise carpets”. Kurt Erdmann suggested that this type of carpet should be better described as "Shah Abbas carpets".

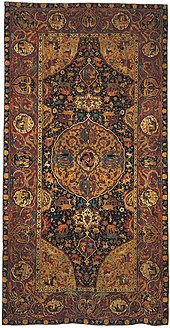

Medallion carpets

From the early Safavid period, the division into medallions and corners became the most common design principle. The middle of the carpet field is taken up by a round shape, the medallion. In the four corners of the field there are quarters of the same shape, the corner medallions. The design of the pattern is symmetrical, mirrored on the horizontal and vertical central axis. The designer of the pattern only needs to design a quarter of a carpet as a knot pattern. Often the medallion is assigned to cartouches and shield-shaped accompanying motifs in the longitudinal direction of the field.

Medallion carpets are divided into two groups, one with figurative and another with purely floral patterns.

- The best-known Safavid medallion carpet with figurative representations is the "Milanese Hunting Carpet" of the Museo Poldi Pezzoli, with inscriptions dated to the time of Shah Tahmasp I's accession to power. Its medallion is almost circular and corresponds to three quarters of the width of the field. The corner medallions are exact quarters of the central medallion. The riders and animals are axially symmetrical, both horizontally and vertically, so they are subordinate to the medallion structure. It is characteristic of the early carpets from this group that the pattern level of the figures is independent, and the medallion pattern can exist independently of the figurative motifs used. In later pieces such as the “Jagdteppich” from the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna or the “Rothschild” silk medallion carpet in Boston, figurative representations also appear in the borders. Stylistically, the Viennese hunting and the Boston Rothschild carpets represent further developments of the Milanese carpet and were probably knotted in Kashan, the center of Safavid silk weaving. The so-called “Sanguszko” carpets, structurally related to the “vase technique” carpets, date from the second half of the 16th century. With them, the classic medallion structure is modified, the corner medallions are usually quarters of a separate pointed oval. However, the rich figurative decoration is in the foreground. With a large variety of colors, the figures are drawn elegantly and safely.

- A group of small-format medallion carpets with floral motifs , mostly assigned to Kashan, emerged at the beginning of the 17th century and led over to the so-called “Polonaise” or “Shah Abbas” carpets.

Spiral tendrils carpets

Spiral tendril carpets are also known as “ Herat ” carpets under the name of their place of origin, presumably in East Persia . Axially symmetrical tendril systems cover the field on a mostly wine-red background. At their points of contact and intersection there are diverse palmetto blossoms, mostly with a flamed contour. The dark green or blue primed borders are traversed by wavy tendrils. In the earliest known pieces from the mid-16th century, animals and animal fighting scenes can still be found. Mostly of a large format, its tendrils are delicate, the palmette flowers large, the figurative representations are arranged exactly symmetrically. Carpets with more rigid tendrils and bands of clouds with a narrower color palette and lancet leaves divided into two colors are assigned to the 17th century. This type of carpet was exported on a large scale and depicted in Dutch paintings of the Renaissance period. It was also re-knotted in India and also exported to Europe.

In 2011 the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg was able to acquire a large fragment of a Safavid spiral vine carpet with depictions of animals, which complements a fragment that has been in the museum's possession since 1967. On the basis of technical weaving details such as the exactly matching coloring of the silk warp threads, it could be clearly demonstrated that the two fragments were part of a single, originally about 2.5 × 5.6 m large carpet. The carpet was cleaned and restored, the fragments brought together. The pattern of the carpet consists of a linear system of spiral tendrils, which connect cut flower ornaments. There are recognizable plastic groups of fighting animals. The impression of three-dimensionality is reinforced by the overlapping of the flower ornaments with individual bands of clouds. Influences of Chinese art can be seen in the fighting pairs of animals (lion and qilin ) as well as in the dynamically drawn bands of clouds. Two different Chinese artistic traditions have flowed into this design: tendrils and flower motifs come from Chinese porcelain art , the depictions of animals from Chinese painting and the Persian book illumination influenced by this. A treatise by Sadiqi Beg, the head of the book workshop Shah Abbas I (r. 1587–1598), distinguishes between spiral tendrils ( islimi ), Chinese flower motifs ( khatai ) and cloud shapes on the one hand, and figures and animals on the other. After the Mongol conquest and the establishment of the Ilchanate, the strong growth in trade with China in the 16th century brought a wealth of new patterns into the fine arts of the Persian court manufactories, which were ultimately also incorporated into the design of carpet patterns.

"Vase technique" carpets from Kermān

A special group of Safavid carpets was identified by May H. Beattie on the basis of technical and structural similarities and assigned to the Kerman region . Some of the carpets made using the "vase technique" show a directed pattern of flowers and plants emerging from vases. However, the technical term is used regardless of the carpet pattern.

Seven different types can be distinguished:

- Garden rugs (depictions of formal gardens and watercourses);

- Carpets with a centralized pattern, indicated by a large medallion;

- Multiple medallions with diagonally offset medallions and a row of subdivisions;

- directed patterns with individually arranged small scenes;

- Sickle-leaf pattern in which long, curved, sometimes compound serrated leaves dominate the field;

- Arabesque pattern;

- Grid pattern.

Their common, characteristic structure consists of asymmetrical nodes; the cotton warp threads are staggered and there are always three weft threads. The first and third wefts are made of wool and lie deep inside the pile. The middle weft is made of silk and goes back and forth from the pile to the bottom. As the carpet inevitably wears, the central weft becomes visible, creating a visual effect similar to railroad tracks running across the carpet.

The best-known vase technique carpets from Kerman are those of the so-called Sanguszko group, named after the Sanguszko house , to whose collection the most extraordinary piece once belonged. The medallion and corner design is similar to other 16th century carpets, but the colors and style of the illustrations are special. In the central medallion, pairs of human figures appear in smaller medallions and are surrounded by an animal battle scene. Other fighting animals are depicted in the field, while riders appear in the corner medallions. The main border also contains lobed medallions with huris , fighting animals or peacocks facing each other. Between the medallions of the border, phoenixes fight with dragons. Due to their resemblance to mosaics in the arches of the Ganjali Khan building complex in the Bazaar of Kerman, the completion of which is inscribed for the year 1006 AH / AD 1596, these carpets can be dated to the late 16th or early 17th century. be dated. Two other carpets in vase technique have inscriptions with a date: One bears the date 1172 AH / AD 1758 and gives the name of the knotter: Master Muhammad Sharīf Kirmānī. The other has three inscriptions indicating that it was made by Master Mu'min, son of Qutb al-Dīn Māhānī, 1066-7 AH / AD 1655-6. Carpets in the Safavid tradition were still knotted in Kerman after the fall of the dynasty in 1732 (Ferrier, 1989, p. 127.).

The end of Abbas II's reign in 1666 marked the beginning of the end for the Safavid dynasty. The declining country has been repeatedly attacked on its borders. A leader of the Ghilzai - Pashtun named Mirwais Hotak sparked an uproar in Kandahar and defeated the Safavid army, led by Gurgin Khan. In 1722 Tsar Peter the Great conquered many of the Caucasian territories of Persia in the Russo-Persian War (1722–1723) , including Derbent , Şəki , Baku , as well as Gilan , Mazandaran and Gorgan . In 1722 the Afghan army of Mir Mahmud Hotaki marched through eastern Persia and took Isfahan . Mahmud proclaimed himself Shah of Persia. The Ottomans and Russians took advantage of the resulting confusion and annexed further territories. These events put an end to the Safavid Empire.

Masterpieces of Safavid carpet weaving

AC Edwards opens his well-known book on Persian carpets with the description of eight masterpieces from the Safavid period:

- Ardabil Carpet - Victoria and Albert Museum

- Jagdteppich - Museum of Applied Arts (Vienna)

- Chelsea Carpet - Victoria and Albert Museum

- Animal and Flower Carpet - Museum of Applied Arts (Vienna)

- Rosenfeld vase carpet - Victoria and Albert Museum

- Medallion carpet with animals and flowers and a ribbon of inscriptions - Museo Poldi Pezzoli , Milan

- Medallion carpet with inscription, animals, flowers and ribbon of inscriptions - Metropolitan Museum of Art , Accession Number: 32.16

- Medallion carpet with animals and trees - Musée des Arts décoratifs (Paris)

Gallery: Persian carpets from the Safavid period

Zayn al-'Abidin bin ar-Rahman al-Jami, miniature, early 16th century, Walters Art Museum

Ardabil carpet in the LACMA

Hunting carpet, knotted by Ghyath ud-Din Jami. Wool, cotton, silk, 1542-3. Museo Poldi Pezzoli , Milan

"Imperial carpet" (detail), 2nd half of the 16th century, Persia. Metropolitan Museum of Art , New York

Carpet by Mantes , Safavid, Louvre

Afsharid (1736–1796) and Zand dynasties (1750–1796)

The territorial unit Persian was Nadir Shah , a warlords from Turkic the Afsharid Dynasty restored from Chorasan. He defeated both the Afghans and the Ottomans, reinstated the Safavids as rulers and negotiated with the Russian Empire over the return of the Caucasian territories of Persia in the Treaties of Resht and Ganja. In 1736 Nadir was crowned Shah himself. Nothing is known about carpet manufacture from the Afsharid period and the subsequent Zand dynasty . Edwards describes the carpet weaving from this period as an "insignificant craft".

Qajar dynasty: 1789–1925

In 1789 Aga Mohammed Khan was crowned Shah of Persia, the founder of the Qajar dynasty, which established order and comparatively peaceful conditions in Persia for a long time. Economic life awoke. Three important Qajar rulers, Fath Ali Shah , Nāser ad-Din Shah , and Mozaffar ad-Din Shah revived ancient traditions of the Persian monarchy. The carpet weavers from Tabriz took advantage of this opportunity by expanding their manufacturing operations from around 1885 and thus becoming the founders of modern carpet weaving in Persia. As early as 1840, numerous carpets were made that contained motifs from lithographed, scaled-down and coarser court miniature paintings, illustrations by Schahname and the Chamsa of Nezami .

Pahlavi Dynasty: 1925–1979

In the period after the Russian October Revolution , Persia was again the scene of clashes. In 1917 Great Britain used Persia as a base for an intervention in the Russian Civil War . The Soviet Union responded by annexing parts of northern Persia and established the short-lived Soviet Socialist Republic of Iran there . By 1920 the Persian government had given de facto control of the country to British and Soviet forces.

In 1925, with the support of the British government , Reza Shah Pahlavi deposed the last Shah of the Qajars, Ahmad Shah Qajar , and founded the Pahlavi dynasty . He established a constitutional monarchy that lasted until the Islamic Revolution in 1979. Reza Shah introduced social, economic and political reforms in his country, which was renamed Iran at his will . To legitimize their rule, Reza Shah and his son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi tried to revive old Persian traditions. Carpet knotting was also promoted, often with a return to traditional patterns from the Safavid court manufactory, and played an important part in these efforts. In 1935 Reza Shah founded the "Iran Carpet Company", which brought carpet production under national control. Carefully executed carpets were knotted for export and also used as diplomatic gifts to other countries.

The Pahlavi dynasty modernized and centralized the Iranian administration, trying to exercise effective control and authority over all of its citizens. Reza Shah was the first monarch to have modern weapons at his disposal. The military enforced his orders. In 1930 the nomadic way of life was declared illegal, and traditional tribal clothing and the use of yurts and tents were banned in Iran. Unable to roam, the nomads lost their herds and many died of starvation. During the 1940s and 1950s, while Iran was embroiled in World War II, and after Reza Shah was forced to abdicate in 1941, the nomadic tribes were able to live in relative peace. Mohammed Reza Shah consolidated his power during the 1950s. The land reform program of 1962, part of the White Revolution, offered advantages for land workers without landed property, but destroyed the traditional political organization of nomadic tribes such as the Kashgai and their traditional, nomadic lifestyle. The centuries-old tradition of nomadic carpet weaving, which was already seriously affected by the introduction of synthetic dyes of poor quality in the late 19th century, was almost destroyed by the last imperial dynasty of Iran.

Around 1970 J. Opie observed that traditional carpet weaving had almost come to a standstill among the large nomadic tribes.

Modern

After the Islamic Revolution , little information was initially available about carpet production in Iran. During the 1980s and 1990s, European customers became interested in Gabbeh carpets, which were originally made by the nomadic tribes for their own use and which differ from planned manufactory designs through their naive, abstract patterns, the coarse knotting and the use of natural colors .

In 1992 the first Grand Persian Conference and Exhibition showed modern Persian carpet designs for the first time. Iranian master weavers such as Razam Arabzadeh or Hossein Rezvani exhibited carpets that are made using traditional techniques, but show unusual modern patterns. After the “Grand Conferences” are repeated at regular intervals, two trends are currently emerging in Iranian carpet production. On the one hand, you see modern and innovative artistic designs, invented by the Iranian manufacturers, who carry the old tradition forward into the 21st century. On the other hand, the renewed interest in natural colors was taken up by the commercial side. The companies commission weavers from tribal villages with the production of carpets, supply the material and information on the design, but allow the weavers a certain degree of artistic freedom. Thus, the carpet-knotting business again offers a source of income for the Iranian rural population, especially for former nomadic tribes.

As a commercial household product, Persian carpets today face competition from other countries with lower wages and cheaper production methods: machine-made loop pile or hand-made carpets with a loop weave produce carpets with an “oriental” pattern, but without artistic value. Traditionally hand-knotted carpets in natural colors achieve higher prices because they are made with a high level of manual labor, which has essentially not changed since ancient times.

Manufacturing

Overview: production of a knotted carpet

Traditionally hand-knotting a rug is a time-consuming process that can take months to even years, depending on the size and quality. Carpets are made on a loom . Warp threads are stretched on this, into which rows of knots are alternately tied and weft threads are woven in.

The weaving of the carpet begins from the bottom of the loom by inserting a number of weft threads across the warp threads . The warp and weft threads form the basis of the carpet. The edges on the narrow sides often consist of more or less wide strips of flat woven fabric without pile. Knots made of wool, cotton or silk yarn are then tied next to each other around the warp threads. When a series of knots is completed, one or more weft threads are woven in to hold the knots in place. The weft threads are knocked down onto the row of knots with a comb-like instrument and the tissue is thus compressed. When the pile is finished, a flatweave edge is often added again before the carpet is removed from the loom. The protruding ends of the warp threads are attached and form the fringes. The long sides of the carpet are also attached and form the edges ("Schirazeh" or incorrectly "Schirazi", English: selvedge). The pile is then shortened to a uniform length and the carpet is then washed.

Traditional forms of looms in Persia

The task of the loom is to maintain the tension of the warp threads and to provide devices to hold them on different levels ("fans") and thereby to be able to guide the weft threads more easily above or below a warp thread through the fabric.

Horizontal loom

The horizontal loom is the simplest form; its beams are laid on the ground and fastened to the earth with stakes. The necessary tension of the warp threads is secured by driven-in wedges. This simple loom is suitable for the nomadic way of life because it is easy to assemble or dismantle and easy to transport. Carpets that are knotted on horizontal looms are often small in size. As the loom is set up and taken down more often, the tension of the warp threads will be different, so that the carpet will end up being more irregular and not as flat on the floor as a carpet made on a stationary, professional loom.

Upright looms

The stationary vertical looms are technically more advanced and are used in village and urban manufactories. There are three types of upright looms, which can be technically modified in different ways: the fixed village loom, the Tabriz or Bunyan loom, and the roll-bar loom.

- The fixed village loom is mainly used in Iran and consists of a fixed upper and a movable lower beam ("fabric beam"), which is fastened in slots in the side beams. The correct tension of the warp threads is created by wedges that are driven into the slots in the side bars. The knotters work on a height-adjustable plank, which is raised higher and higher as the carpet progresses. A carpet produced on such a loom can be as long as the loom is high.

- The Tabriz loom, named after the city of the same name, is traditionally used in northwestern Iran. The warp threads continue behind the loom like a vertical conveyor belt. The tension of the warp threads is adjusted and maintained with wedges. The knotters maintain a fixed position. When a section of the carpet is finished the warp threads are loosened and the section is pulled down onto the back of the loom. This process repeats itself until the carpet is finished. For technical reasons, a carpet can be knotted on a Tabriz loom that is a maximum of twice as long as the height of the loom.

- The scroll bar loom is widely used in the countries that manufacture carpets. It consists of two movable bars around which the warp threads are wrapped. The beams are attached with notches. When a section of carpet is ready it is wound onto the lower beam. In theory, a carpet of any length can be made on a scroll bar loom. In some, especially in Turkish, factories, several carpets are knotted one behind the other on the same warp threads and only cut apart at the end.

More tools

A number of important tools are needed to knot: a knife to cut the thread; a heavy, comb-like instrument with a handle ("comb beater") to compact the weft threads and knots, scissors to shorten the pile after one or a small number of rows of knots have been introduced. In Tabriz there is a tying hook at the tip of the knife, with which the knots can be tied faster. Sometimes a steel comb is used to comb out excess yarn when a series of knots is complete.

Additional instruments are used to further densify the pile, especially in those regions of Iran that make very fine carpets. In Kerman the weavers use a special tool in the form of a sword that is inserted horizontally into the shed (the space between the two levels of the warp threads). In the region around Bidschar , a nail-like rod is inserted between the warp threads and tapped firmly to compact the fabric even further. Bidschar is also known for his wet weaving technique. Pile, warp and weft threads are continuously moistened to keep them compact during the knotting process. After drying, wool and cotton expand, creating a very heavy and stiff fabric. Bidschar carpets are so tightly knotted that they are difficult to fold without damaging the fabric.

Other blades were traditionally used to shear the pile to an even height after the carpet was completed. Today this work is done faster and easier by machines that are guided over the carpet in a similar way to a sanding machine. If a relief effect is to be created, the pile is cut diagonally along the color borders at the desired points. Relief effects are very rare in classical Persian carpets, and are often seen in Chinese and Tibetan knotted carpets.

Carpet weavers on an upright village loom, Antoin Sevruguin around 1890

be crazy

The fibers of wool, cotton or silk are spun either by hand using a hand spindle or mechanically using a spinning wheel or industrial spinning machines by drawing and twisting the fibers into a yarn. Several individual yarns are usually twisted into one thread for greater thickness and stability. The direction in which the yarn is spun and twisted is referred to as either the “Z” or the “S twist”. Usually hand-spun single yarns are spun with a Z-twist and then twisted with an S-twist. This also applies to almost all oriental carpets, including the Persian carpet, with the exception of the S-spun and Z-twisted yarns of the Mamluk carpets.

Dyeing the yarn

The process of dyeing begins with the preparation of the yarn through pickling in order to make it receptive to the actual dyes. The dyes are dissolved in water and the wool is added to the dye solution for a certain period of time. The dyed yarn then has to dry in the air and in the sun. Some dyes, especially dark brown, require iron-containing stains that can attack the wool of the yarn. Therefore, brown-colored pile areas wear out faster and more, which can lead to a relief effect in antique carpets.

Vegetable dyes

Natural dyes used in Persian carpets are obtained from plants and insects. In 1856 the English chemist William Henry Perkin developed the first aniline dye , mauvein . A variety of other synthetic colors were subsequently invented. Compared to natural dyes, they were cheaper and easier to use. Their use in knotted carpets has been documented since around the mid-1860s. Synthetic dyes have changed the production of knotted carpets so fundamentally (disadvantageously) that the tradition of dyeing with natural dyes was almost completely lost. It was revived in Turkey in the early 1980s: chemical analyzes of wool samples from antique carpets led to the identification of the plants used for dyeing, and the dyeing recipes and procedures were experimentally reconstructed.

Accordingly, the following plants were used to dye carpet yarns:

- Red from the root of the madder (Rubia tinctorum) ;

- Yellow from different plants, including onion skins (Allium cepa) , different types of chamomile ( dog chamomile (Anthemis) , real chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) ), and milkweed (Euphorbia) ;

- Black : gall apple , acorns , gerber sumac (Rhus coriaria) ,

- Green : double coloration with indigo and yellow dyes,

- Orange : double coloration with madder and yellow dyes,

- Blue : Indigo from the indigo plant (Indigofera tinctoria) .

Some dyes such as indigo or madder were commodities and were widely available. Yellow or brown dyes were mostly obtained locally from plants in the area and therefore vary greatly from region to region. Many plants provide yellow colorings, in addition to the above, also grape leaves and pomegranate bark. Saffron is often mentioned as a yellow dye, the actual use of this precious but not very durable dye has not yet been clearly proven.

In Iran, traditional dyeing with vegetable dyes was revived in the 1990s. The general interest of customers in traditionally dyed carpets met dye masters like Abbas Sayahi, who had retained his knowledge of traditional Iranian recipes.

Insect dyes

Crimson colors are also obtained from the resinous secretions of the cochineal scale insect (Coccus cacti) and other scale insects of the species Porphyrophora ( Porphyrophora hamelii (Brandt) , Armenian scale insect; Porphyrophora polonica , Polish scale insect). Cochineal red, the so-called “laq”, was first imported from India, later from Mexico and the Canary Islands. Carmine colors were mostly used in regions where madder did not thrive, such as western and north-western Persia.

Synthetic dyes

Early synthetic dyes were found to be extremely fragile to light and moisture. They were so disappointing that Nāser al-Din Shah and his successor Mozaffar al-Din Shah tried to restrict their distribution by law and with tax measures. (Gans-Ruedin 1978, p. 13.). In contrast to this, almost any color and color intensity can be achieved with modern colors. With a carefully made modern carpet, it is almost impossible to tell with the naked eye whether natural or artificial colors have been used.

Abrash

The appearance of fine deviations within the same color is called "abrash" (Turkish abraş , literally, "blotchy, spotted"). Abraz can only be seen in traditionally colored carpets. If abrasch does occur, it suggests that there was probably only one person working on the carpet who did not have enough time or resources to dye all of the yarn that they needed for the carpet at once. So only small amounts of the required yarn were dyed from time to time. When the yarn was used up, new ones were dyed. Because the exact same color is hardly ever achieved a second time with natural colors, the color of the carpet pile changes when a new row of knots is tied with the newly dyed yarn. This change in color suggests that carpets were made by members of a nomadic tribe or in a small village. Abrasch can also be created intentionally by means of predefined color changes in a manufactured carpet.

Gallery: paints and dyes

Madder madder (Rubia tinctorum)

Indigo, collection of historical dyes, Technical University of Dresden

Knotting techniques

Persian carpets are mainly tied with two different knots: The symmetrical knot , also known as the Turkish or “Gördes” knot, is used in Turkey, the Caucasus, East Turkmenistan and some Kurdish areas in Iran. The asymmetrical knot , also known as the Persian or “Senneh” knot, is used in Iran, India, Pakistan, Turkey (for example in the carpets of the Ottoman court manufactory or Hereke carpets), Egypt and China. The term “Senneh knot” is misleading, as symmetrical knots are traditionally used in the city of Senneh.

- To tie a symmetrical knot, one end of the yarn is passed through between two adjacent warp threads and returned to the front under a warp thread, then wrapped around both warp threads like a collar and pulled out between them.

- The asymmetrical knot is tied by wrapping the yarn around only one warp thread and then passing it behind the adjacent warp thread and pulling it forward so that it separates the two ends of the thread. Depending on how the knot is set, it will later open to the right or left.

Asymmetrical knots allow more fluid, often curvilinear ("floral") patterns, while symmetrical knots are more suitable for the strong rectilinear ("geometric") patterns. However, as the Senneh carpets show with their elaborate, fine pattern, which are knotted in symmetrical knots, the fineness of the pattern depends more on the skills of the weavers than on the type of knot used.

- Another knot that is often used in Persian carpets is the " Jufti " knot, which is tied around four warp threads instead of two. A usable carpet can also be made with jufti knots, and jufti knots are often used in the larger, single color areas of a carpet to save material and time. Since carpets that are partially or fully knotted with Jufti knots only require half the material required for traditional knotting, their pile is less resistant and the carpets are not as durable.

Usually, the knots are knotted row by row on top of each other on the same warp threads. If the knots per row are knotted laterally offset to one another by a warp thread, one speaks of " offset sequence " or "offset" knot. This technique allows the knotting of finer curvilinear patterns, especially diagonals, and is often used with Turkmen carpets and rarely with Persian carpets.

There are also further structural criteria: The two warp threads belonging to a knot are either in the same plane (as shown) or in two planes separated by a taut weft thread (" layered "). With the Persian knot, the fully entwined warp thread lies on the underside of the carpet. Most carpets knotted in the Persian knot are layered, carpets of the nomadic tribes are more often unlayered. Due to the lower space requirement of the layered knotting technique, such carpets appear finer than the unlayered ones. Old carpets from western Persia ( Tabriz , Heris , Bidschar , Senneh, Hamadan , Farahan ) are knotted in a symmetrical knot.

Knot density

The number of knots is given in knots per square decimeter or, for example in English-language auction catalogs, in knots per square inch ( kpsi ) (conversion: dm²: 15.5 = si). The best way to count the knots on the back of the rug. If the warp threads are not layered too deeply, the two loops of a knot will remain visible and must be counted as one knot. Only one loop is visible in deep layers. The best way to recognize this is to look for sections of the pile with individual knots in different colors, for example in diagonals or lines.

Additional information can be obtained by specifying horizontal and vertical nodes separately. In the case of particularly finely knotted carpets (e.g. silk carpets from Kashan), one often finds a ratio of horizontal to vertical knots of 1: 1, for which the weaver requires considerable skills. Carpets made in this way are particularly dense and durable.

The knot density provides information about the fineness of the knot and thus the amount of work involved in making the carpet. The artistic and practical value of the carpet hardly depends on the number of knots, but on the quality and execution of the pattern and the materials used. Persian carpets from Heris , for example, often have a very low number of knots compared to the extremely finely knotted carpets from Kashan, Qom or Nain, but are often artistically satisfactory and very durable.

Patterns and ornaments

Certain, repeating ornaments, motifs, and patterns are a key feature of every Persian rug. The traditional conventions have remained unchanged for centuries. A Persian carpet has a large central field, which is surrounded by a wide main border and several secondary or guardian borders. The main border pattern is mostly floral, or contains arabesques, or both. The main border can also be divided into cartridges . The patterns of the secondary borders are subordinate to the main border and are kept correspondingly simple. Usually small ornaments are repeated. The pattern of the field is also subject to the convention. The most important thing is balance . The two halves of the field must be identical. With most carpets, the upper and lower halves must also be approximately symmetrical, but there are also traditionally oriented patterns such as prayer or vase carpets. As carpets are the most important piece of furniture in traditional room arrangements, their patterns should be visible from every direction.

Rectilinear and curvilinear design

A pattern can be described as either rectilinear (or "geometric") or curvilinear (or "floral"). Curvilinear patterns show rounded, flowing lines, often in the form of plant-like ornaments such as tendrils or curved leaves. The drawing is more fluid, the knotting is often complicated. Rectilinear patterns appear stronger and more angular. It is also possible to draw floral patterns in a rectilinear shape, these are then usually more abstract or more stylized. For this reason, the term pair “rectilinear / curvilinear” is preferred to terms such as “floral / geometric” in recent literature. Rectilinear pattern shape is associated with village or nomad carpets, while the more complex curvilinear patterns are reserved for the artistic planning of a manufactory.

Outline of the field, medallion and border

The pattern of a carpet can be described by the way its ornaments are arranged in the pile. A basic pattern can dominate the whole field, but the surface can also be covered by repeating ornaments.

In regions with traditional local patterns that have been respected since time immemorial, carpet weavers can work from memory, as the specific patterns are part of the family or tribal tradition. For the less sophisticated, often rectilinear patterns, this is completely sufficient. More elaborate, especially curvilinear, patterns require a carefully planned design. For this purpose, the samples are drawn to scale in the original colors on graph paper, often with the help of computer programs today. The resulting plan is called a "box". The knotters tie a knot in the carpet for each box on the graph paper. Each node thus represents a " pixel " from the entirety of which the sample image is created. The main traditional patterns have remained unchanged for centuries.

The area of the carpet field is arranged and ordered according to convention in such a way that the pattern is always recognizable as "Persian" in its entirety, despite all the diversity in detail. A pattern can be repeated and fill in the field completely ( "pattern report" or "allover" pattern). When the end of the field is reached, it happens that the pattern appears cut off at the edge. The impression then arises that the pattern continues beyond the border. This way of dealing with patterns, especially geometric ones, is generally typical of Islamic art. The field pattern of an oriental carpet is often based on complicated, superimposed spiral and tendril patterns in " infinite rapport " (Erdmann, 1943, p. 20.).

The pattern elements can be structured hierarchically. A typical pattern is the medallion , a symmetrical ornament mostly in the center of the field. Sections of the medallion or similar, corresponding elements fill the four corners of the field. The Persian "Lechek Torūnj" (medallion-and-corners) arrangement developed in Persia from patterns that were designed in the 15th century for book covers and miniatures . It found its way into the repertoire of carpet designs during the Safavid period in the 16th century. More than one locket can be used, and these can come in a variety of shapes and spacings in the field. The field can be divided into rectangular, square or diamond-shaped compartments.

In contrast to Anatolian carpets, the Persian carpet medallion usually represents the primary pattern. The infinite repeat of the field is subordinate to it, so that the impression is created that the medallion is "floating" on the field (Erdmann, 1965, pp. 47–51.) .

In most Persian carpets, the field is surrounded by stripes, the borders. The number of these varies from one to more than ten, but usually there is a wider main border , which is framed by narrower side or guardian borders . The main border is often filled in with more complex patterns. The side borders have simpler patterns such as meandering vine tendrils. The field and borders are traditionally always separate, but the pattern can also be varied in such a way that the field extends into the border. This is more commonly seen in 19th century Kerman carpets. It is believed that elements from French tapestries from the Aubusson or Savonnerie factories were the inspiration here.

The connection of the border corners poses a particular challenge for the design. The ornaments should be knotted in such a way that the pattern continues around the corner between the horizontal and vertical border without interruption. This demands great skill from the weaver when she works without cardboard. If the ornaments in the corners connect to one another correctly, one speaks of "dissolved" corners or "successful corner solution". In village or nomad carpets that are knotted without cardboard, the corners are often not dissolved. The knotters simply break off the pattern of a border when, for example, the horizontal border reaches the intended height, and begin with the vertical border. It also happens that the knotters improvise with the corner solution, i.e. do not lead the ornament completely around the corner. The analysis of the corner solutions makes it possible to distinguish nomad or village carpets from the production of urban manufactories.

Field motifs

The field, or sections of it, is mostly covered by smaller motifs. Although the pattern of the individual ornament can be very complicated, the overall impression is still homogeneous. Individual pattern elements can also be grouped and form a more complex motif:

- Boteh : The boteh pattern ( pers .: bush or bundle of leaves ) is also used in all countries that make carpets. Boteh can be displayed in both curvilinear and rectilinear styles. As with many of the very ancient patterns, its meaning is unclear. It is interpreted as the “Flame of Zarathustra ”, pine, palm, almond or pear or the imprint of a clenched fist in clay. In fact, it resembles a leaf pattern and, in its simplest form, is very similar to a serrated leaf. The most finely crafted boteh patterns can be seen on the Kerman carpets. Carpets made from Saraband , Hamadan and Fars sometimes show the boteh as a continuous pattern. On the old Mir and Saraband carpets, it often forms the only pattern in the field when lined up.

- Gül : (Pers./Turk .: Rose ): The Gül pattern is often found on Turkmen carpets, which are also made in Iran. Small round or octagonal medallions are arranged in rows across the entire field. Although the Gül motif itself is very complicated and colorful, the lined-up representation on the mostly monochrome red field creates a rather strict and monotonous impression. In Caucasian carpets, the Gül motifs are assigned a heraldic function because the respective Turkmen tribe can be identified from the pattern of the Gül.

- Herati : named after the city of Herat in what is now Afghanistan; composite motif of a rhombusenclosinga rosette . The corners of the diamond are connected with smaller rosettes. This ornament is in turn surrounded by lancet leaves, sometimes also referred to as fish ( mahi ). The pattern probably originated in Eastern Persia, but is used in all regions of the “carpet belt”. The Herati pattern appears particularly often in carpets from Bijar .

- Chartschang : (Persian crab ) The main motif consists of a large oval motif that looks like a crab. The pattern is widespread, but sometimes shows a clear resemblance to the palmette pattern of the Safavid period and the "Shah Abbasi" pattern. The “legs” of the crab could therefore correspond to stylized arabesques in a rectilinear style.

- Minah Chani : The pattern consists of flowers arranged in a row, which are connected by (often curved or circular) lines and in the middle of which there is a smaller flower. The pattern often covers the whole field. It is often seen on carpets from the Waramin area .

- Sil-e Sultan : consists of two vases placed one above the other, decorated with roses and flowering branches. Mostly there are also birds on the vase. This very young motif was created in the 19th century.

- Shah Abbasi : This pattern is composed of grouped palmettes. It is often seen in city carpets from Kashan , Isfahan , Mashhad and Nain .

- The Gol Henai (pers .: henna blossom ) is not very similar to the plant that gave it its name, but rather resembles the Persian garden balsam ( Impatiens balsamina ), and is also compared in western literature with a horse chestnut blossom.

- The Bid Majnūn - or weeping willow motif is often depicted together with cypress, poplar and fruit trees, mostly in a rectilinear design. It probably has its origin in the Kurdish pattern tradition, as the earliest carpets of this type come from the Bijar area .

- Other pattern elements consist of old motifs such as the tree of life , or floral and geometric elements such as stars, rosettes or palmettes.

Edge motifs

- Tosbagheh : According to a very old tradition, the Herati pattern in the field is accompanied by a main border, the pattern of which consists of large rosettes or palmettes alternating inwards towards the field or outwards, each accompanied by a leaf ornament on both sides. The composite ornament points alternately outwards or inwards towards the field. The rosettes are connected by tendrils from which the leaves extend. The ornament looks distantly like a turtle (viewed from the front). A border with this ornament is therefore called a "Tosbagheh" or "turtle" border. In Tabriz the ornament was known as the "samovar" ornament.

- Edge boteh : corresponds to the normal boteh motif

- Kufi border: takes its name from its similarity to an Arabic font . The ornaments usually appear white on a red background.

- serrated leaves : consists of a series of serrated leaves (e.g. grapevines)

Ornaments

- eight-armed star

- rosette

- swastika

- Greek cross , rare paw cross

Gallery: Common motifs on Persian carpets

Formats

The classic carpet formats used in Persia itself differ from the formats produced for the export market. Traditional Persian rooms are rather long and narrow, as long wooden beams for the ceilings were limited. In the middle of the room there was usually a magnificent main carpet, Ghali (Farsi:قالی) or " mian farsh ", which was rarely trodden . At the head of the room was a head rug, Kelleghi , and to the side of the main rug, there were two long, narrow side runners in Kenareh format. Larger and wider carpets were used less often in traditional living spaces and were more likely to be made for the Western European and American markets.

- Ghali ( Persian قالی, '(Main) carpet'): large-format carpet for the center of the room (190 × 280 cm).

- Dosar or Sedschadeh : The term comes from Farsi do , "two" and sar , a Persian unit of measurement that corresponds to about 105 cm. Dozar-sized carpets measure approximately 130–140 cm by 200–210 cm.

- Ghalitcheh ( Persian قالیچه): Carpet of very fine quality in Dosar format.

- Kelleghi or Kelley : long format , approx. 150–200 × 300–600 cm. This format is traditionally laid out at the head of a ghali carpet ( kalleh means "head" in Farsi).

- Kenareh : Smaller long format , 80–120 cm × 250–600 cm. Traditionally laid out along the long side of the main carpet ( kenār means "side" in Farsi).

- Saronim : Corresponds to 1 ½ sar . These smaller carpets are about 150 cm long.

- Sarcharak : Format approx. 0.80 m × 1.30 m

- Poschti : cushion, approx. 0.40 m × 0.60 m

- Pardeh : Format approx. 2.40 m × 1.40 m

Oversized carpets were ordered by the Shahs of the Pahlavi dynasty to decorate the Saadabad and Golestan palaces; Giant formats are made today, for example, for newly built large mosques such as the Great Sultan Qaboos Mosque . Special formats such as square or round carpets rarely occur, mostly as export goods.

Classification

Persian carpets can - in addition to their place of manufacture - be roughly classified based on the social context of their weavers. Carpets were and are produced by nomadic tribes as well as in villages, towns or (earlier) in court factories.

Nomad and ethnic tribes

The carpets of the nomads are knotted by different ethnic tribal groups, which differ from each other through different histories and traditions. Originally the tribes made carpets mainly for their own use, so the nomad carpets have retained the original patterns and knotting even more than the more commercialized carpets from the settlements and cities. After the nomadic way of life had changed significantly in the course of the 20th century towards more sedentarism, traditional carpet production almost came to a standstill in the 1970s, but was revived in the decades that followed.

Criteria for a knot in the nomadic tradition are (Brüggemann / Boehmer 1982, p. 58 f.):

- Unusual materials such as goat hair warp threads or camel wool in the pile;

- High quality wool with a long pile;

- small format as it fits on a horizontal loom;

- irregular format due to the frequent assembly and disassembly of the loom, which leads to uneven tension of the warp threads;

- stronger abrash;

- longer flat woven fabrics form the ends.

Technical characterization of Persian nomad carpets

| Kurds | Bakhtiari & Luri | Chahar Mahal | Qashqai & Khamseh | Afshars | Baluch | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| node | symmetrical | symmetrical | symmetrical | symmetrical & asymmetrical, left opening | symmetrical & asymmetrical, right opening | predominantly asymmetrically left-opening, rarely right-opening or symmetrical |

| Chain shot | Wool, sometimes cotton. Warp white or brown, weft brown or red | Wool, goat hair, cotton. Warp brown or white, weft brown or red. | Cotton, weft sometimes blue | Wool, weft white (Q.) or white and brown (Kh.), Weft natural color or red (Q.), or red and brown (Kh.) | Wool, warp white and brown, weft orange-red or pink | Warp white, weft dark brown, later also cotton |

| Shirazeh | Weft reversal or wrap | dark brown or goat hair, wrapped | wrapped in black wool | wrapped, two-tone (Q.), weft reversal and wrapping, natural-colored or dyed wool (Kh.) | Reversed weft, dyed wool | wrapped in brown wool or goat hair |

| degrees | Flat weave, 2 cm to very wide | Flat weave, 2–8 cm, natural color or striped | Flat weave, 2–5 cm | Flat weave, 2–5 cm, often with intertwined or brocaded stripes | Flat weave, 2–15 cm, natural colors or colored stripes | 2–25 cm, colored stripes, paperback |

| Main colors | Yellow, natural, or corroded brown | Dark blue, light red, deep yellow | Dark blue, light red, deep yellow | bright, radiant red, different shades of blue, rarely yellow, green | Yellow, salmon red | Bright blue |

Data from O'Bannon, 1995

Kurds

The Kurds are an ethnic group who predominantly live in an area that includes the areas in the respective border region of southeastern Turkey , western Iran , northern Iraq , and northern Syria . The high population and wide geographical distribution of the Kurds result in a wide spectrum of patterns, ranging from the rough and naively designed nomad carpets to the most sophisticated patterns of urban manufacture. The carpets can be as fine and lightly knotted as those from Senneh or as heavy and dense as the Bidschar carpets.

Senneh carpets

The city of Sanandaj , previously called Senneh, is the capital of the Persian province of Kordestān . The carpets knotted here are still known under the trade name “Senneh”, even in today's Iran. They are among the finest Persian carpets with knots up to 6200 / dm². The pile is shorn very shallow, the bottom made of cotton, and in antique silk rugs also made of silk. The typical Senneh carpet is relatively finely knotted and has a 'grainy' reverse side due to the heavily twisted pile thread and simple cotton weft. Some carpets have warp threads made of silk which, when dyed in different colors, produce different colored fringes, which are often referred to as "rainbow fringes" in the trade. These, as well as the frequently repeated boteh patterns, indicate a possible influence from India during the Mughal period. The field often appears in the basic color blue or pale red. The most common pattern is the Herati pattern on a contrasting base color. More realistically depicted floral patterns also appear, but seem to have been knotted for export.

Bidschar carpets

The city of Bijar is located around 80 km northeast of Sanandaj. These two cities and their surroundings were known as major centers of carpet weaving as early as the 18th century. The carpets from the Bidschar region show different patterns than the Senneh carpets. A distinction is made between “urban” and “village” Bidschar carpets. Bidschar carpets are characterized by their tightly packed pile, which is created using the special technique of wet weaving and with the help of a special tool. The warp, weft and pile yarn are kept wet throughout the knotting process. As the finished carpet dries, the wool expands and the fabric becomes very compact. In addition, the fabric is compacted during the knotting process by vigorous hammering on a nail-like device that is guided between the warp threads during the knotting process. The warp threads are alternately deeply layered, the fabric is further compressed by using weft threads of different thicknesses. Usually one out of three weft threads is significantly thicker than the others. The nodes are symmetrical, their density is 930–2100 / dm², more rarely even over 6200 / dm².

The colors of the Bidschar carpets are very exquisite, light and dark blue and rich to pale madder red. The patterns are traditional Persian, mostly Herati, but you can also see Mina Khani, Harshang, and simpler medallion shapes. Often the pattern is more rectilinear. A characteristic is that the ornaments often lack the usual accompanying contours in contrasting color, especially often with the small-scale pattern elements. Bijar carpets are easier to recognize by their special, stiff and heavy weave than by their pattern. Carpets from the Bijar region are difficult to fold without damaging the base. Carpets in full normal size, which only show examples of possible field and border patterns, are often referred to in the trade as "Wagireh" (pattern carpet). You can often see them in the Bijar region. Bidschar still exports new carpets, often with less sophisticated Herati patterns and good synthetic colors.

Kurdish village carpets

From a western perspective, there is not much information about the production of Kurdish village carpets in particular. We probably have insufficient knowledge because Kurdish carpets have never been specially collected and published in the West. Most of the time a carpet can only be identified as “northwest Persian, maybe Kurdish”.

As is so often the case with village and nomad carpets, the basis of village carpets is usually made of wool. Kurdish sheep wool is of particularly good quality and accepts colors well. A carpet with the characteristic properties of "village production" made of high-quality wool with particularly careful dyeing can be assigned to Kurdish production. In most cases, however, this allocation remains speculative. Most carpet patterns and ornaments are so widespread that they cannot be assigned to a particular tribe or region. There is a tendency to adapt the traditions of the surrounding Turkish and Persian regions in the course of the so-called “model migration”. If unusual deviations occur here, a Kurdish production from the respective area can be assumed. In the opposite case, however, northwest Persian cities such as Hamadan, Zandschan or Mahabad (Sauj Bulagh) have also adopted Kurdish designs in the past. The modern production shown in the “Grand Persian Exhibitions” seems to have deviated from this.

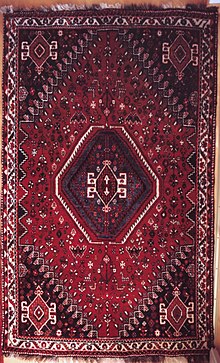

Kashgai

The early history of the Qashqai is in the dark. They speak a Turkic language - dialect similar to that in use in Azerbaijan and are probably under the pressure of the Mongol invasion during the 13th century from the north in the province. Fars immigrated. Karim Khan Zand appointed the leader of the Chahilu clan as the first Il- Chan of the Kashgai. The most important sub-tribes of the Kashgai are the Qashguli, Shishbuluki, Daraschuri, Farsimadan, and Amaleh. The Gallanzan, Rahimi and Ikdir also knotted carpets of medium quality. The carpets made by the Safi Khani and Bulli sub-tribes were considered to be of the highest quality. The carpets are made entirely of wool, mostly with ivory-white warp threads, which distinguishes the Kashqai from the Khamseh carpets, which are closely related in the pattern. Kashgai carpets are knotted with asymmetrical knots, while Kashgai gabbeh usually have symmetrical knots. The warp threads are alternately deeply staggered. The weft threads are dyed in the natural wool color or red. The edges are wrapped with different colored wool, creating a "candy cane" color effect (English: "barber pole"). Both ends of the carpet have short striped flat weaves. As early as the 19th century, workshops were being built around the city of Firuzabad . In these workshops carpets with repeated boteh or herati patterns and prayer carpets similar to the “millefleurs” carpets of contemporary production were made. The Herati pattern often appears stretched and fragmented. The Kashgai are also known for their flat woven fabrics and for the production of smaller, knotted saddlebags, larger bags using flat weave technology ( mafrash ), and their Gabbeh carpets.

The carpets of the Schischbuluki tribe ( lit. "Six Districts") are characterized by small central diamond-shaped medallions that are arranged concentrically from the center. The field is mostly red, details appear in yellow or ivory. Daraschuri carpets are very similar to those of the Shishbuluki, but more coarsely knotted.

After the original lifestyle of the nomads almost came to a standstill during the 20th century, most Kashgai carpets are now knotted in the villages on upright looms and have cotton warp and often weft threads. The patterns traditionally associated with the Kashgai are still used, but it is hardly possible to assign a carpet to a special tribal tradition. Many designs, including the traditional “Kashgai medallion”, which were previously assumed to originate from a real nomadic tradition, have now been shown to originate from the city's manufactory. They were integrated into the weaving tradition of the rural villages through a stylization process.

The revival of dyeing with natural dyes had a strong influence on the Kashgai carpet weaving. Beginning in the city of Shiraz , where the dye master Abbas Sayahi lived, the Gabbeh carpets in particular found great interest among buyers. These were originally knotted roughly from undyed wool for personal use. Since the reappearance of natural colors, they have been knotted in the full range of available colors. In modern production, the design of Gabbeh rugs still remains simple, but follows modern ideas.

Khamseh Confederation

The Khamseh Confederation (from arab.خمسة Kamsa , five [tribes]) was in the 19th century by the Persian government under the Qajar established to the power of weakening Kashgai strains. Five tribal groups of Arab, Persian and Turkish descent with the Arab tribes, the Basseri, Baharlu , Aynallu , and Nafar have been combined. It is often difficult to clearly identify a Khamseh-made carpet. The name "Khamseh" is often used as a trade name or by convention. Warp threads and side fastenings made of dark wool are mostly assigned to the Arab Khamseh tribes. The warp threads are usually not layered, the color scheme is rather dark. A stylized bird pattern ( "murgh" ), arranged around a sequence of small diamond-shaped medallions, is often assigned to the Khamseh. Basseri carpets are asymmetrically knotted, lighter in color, with more open spaces and smaller ornaments and figures. Hardly any carpets are known from the more agricultural region of Darab , where the Baharlu live.

Luri

The Lurs live predominantly in western and southwestern Iran. They are of Indo-European origin. Their language is closely related to the dialect of the Bakhtiari and the southern Kurds . Your carpets come to the market in Shiraz. They usually have a base of dark wool, with two weft threads after each row of knots. Symmetrical and asymmetrical nodes are used. The pattern is often divided into small sections of repeating stars. Diamond-shaped medallions with anchor-like hooks on both tips are also featured.

Afshari

The Afshari , a Turkic tribe , lived in the far east of Iran in the border area with Afghanistan and especially today - due to forced resettlement - in the southern Persian region between Shiraz and Kerman . They mainly made runner-sized rugs and bags of various sizes with rectilinear or curvilinear designs, both with central medallions and "all-over" patterns running across the field. The most common colors are light and pale red. The ends of carpets in flat weave often have many narrow colored stripes.

Baluch

The Baluch live in eastern Iran. They mainly knot small-format carpets and various bags in dark red and dark blue tones, often combined with dark brown and white. Camel wool is also used.

Village carpets

The carpets knotted in the villages of Iran are usually sold in regional market centers and then often have the name of this center as a trade name. Sometimes, for example with the “Serapi” carpet, the name of the village (Sarab) serves as a quality feature: A “Serapi” carpet is a Heri carpet of higher quality. Village carpets can be recognized by their coarser, more stylized pattern.

The following criteria indicate that a carpet comes from village production (Wilber, 1989, pp. 6-10.):

- Smaller format, often Dosar;

- knotted without template;

- Corners not resolved or improvised;

- Irregularities in the pattern structure or in individual ornaments.

Village carpets tend to have warp threads made of wool. Their patterns are not as sophisticated as the curvilinear patterns of the city or factory carpets. They often show abrash and clearly visible errors in detail. When simple upright looms have been used, the tension of the warp threads cannot be kept uniform, so village carpets can be irregularly warped, have irregular sides, and sometimes not lie perfectly flat on the floor. The sirazeh and fringes are worked out differently, not as regularly as with manufactured carpets. Village carpets are less likely to have layered warp threads, and narrower flat weaves at the ends that are not as long as are often the case with nomad carpets. The different ways in which ends and fringes are worked sometimes give clues to the origin of the carpet. Since the most common patterns were and are used everywhere in Iran, the carpet patterns are often not helpful in determining the provenance. A few structural features support identification and are listed accordingly. In order to assess them, the carpet must be available for examination; Illustrations only help if the structural features are clearly shown on them.

Since Edwards' classic description of carpets in 1952, many of the villages of that time have grown into modern cities. Old carpets from former village production are still on the market and can be identified by the characteristics described below. If newly manufactured carpets have the characteristics described, they could have come from a village in the vicinity of the centers mentioned or they could have been made with a conscious reference to regional tradition.

Northwest Iran

Tabriz is the market center of the Iranian northwest. The carpets from this region usually have a symmetrical weave. Heris is a local production center where mainly large-format, space-filling carpets are knotted. The warp and weft are mostly made of cotton, the knotting is rather coarse, but with good quality wool. Prominent central medallions are characteristic of Heri carpets, with strong, rectilinear ornaments, sometimes in repeat. Heri carpets of better quality are known under the name Serapi. In Sarab , runners and galleries with wide main borders are knotted, often camel wool or sheep wool dyed with camel hair is used. Large, connected medallions fill the field. The mostly rectilinear, geometric ornaments are colored pink and blue. Bakshaish carpets have a large shield-shaped medallion and coarsely drawn patterns in salmon red and blue. Karadscha produces runner formats with special square and octagonal rows of medallions.

Western Iran