Thousand and one Night

A thousand and one nights ( Persian هزار و يک شب, DMG hazār-u yak šab , Arabic ألف ليلة وليلة, DMG alf laila wa-laila ) is a collection of oriental stories and at the same time a classic of world literature . Typologically, it is a frame narrative with story boxes .

history

Suspected Indian origins

From the point of view of the earliest Arab readers, the work had the allure of the exotic , for them it comes from a mythical "Orient". The structural principle of the frame story and some of the animal fables contained therein indicate an Indian origin and probably date from around 250. An Indian model has not survived, but this also applies to many other Indian texts from this period. An Indian origin is assumed, but that the core of the stories comes from Persia cannot be ruled out. In addition, there were close ties between the Indian and Persian cultures at that time.

Original Persian version

The Indian stories were probably translated into Middle Persian in late antiquity , under the rule of the Sassanids , around 500 AD and expanded to include Persian fairy tales. The Middle Persian Book A Thousand Stories ( Persian هزار افسان- hazār afsān ), the forerunner of the Arabic collection, has been lost, but is still mentioned in two Arabic sources from the 10th century. Some of the characters in the Arabian Nights also have real models from Persian history, for example the Sassanid great king Chosrau I (r. 531 to 579). Since the Sassanids cultivated close cultural contacts with the Mediterranean region , elements of Greek legends - such as the Odyssey - probably also found their way into the fairy tale cycle in their time.

Translation into Arabic

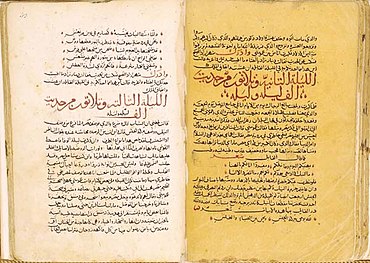

Probably in the later 8th century, a few decades after the spread of Islam in Persia, the translation from Persian into Arabic, Alf Layla ( Thousand Nights ) , arose . This probably happened in Mesopotamia , the old center of the Sassanid Empire and the location of the new capital Baghdad , seat of the Abbasid caliphs . At the same time, the work was " Islamized ", that is, enriched with Islamic formulas and quotations. The oldest fragments are from this time around 850 (so-called Chicago fragment ) and are mentioned in Arabic literature . These translations are characterized by the use of Middle Arabic , an intermediate form between the classical standard Arabic used in the Koran and the Arabic dialects , which have always been reserved for oral use. Around 900, the sister collection One Hundred and One Nights (Arabic Mi'at layla wa-layla ) was created in the far west of the Islamic world. The Arabic title Alf layla wa-layla was first mentioned in a notebook of a Cairo Jew from around 1150 .

In the course of time, further stories of various origins were added to the frame story, for example stories from Arabic sources about the historical caliph Hārūn ar-Raschīd and fantastic stories from Egypt in the 11th and 12th centuries. "Complete" collections, i.e. H. Collections in which a story repertoire was spread over 1001 nights are mentioned in one of the above-mentioned Arabic sources of the 10th century, but it is unlikely that more of them has survived than the story inventory of the cycle of the "Merchant and Djinni". Over the centuries, however, “complete” collections have been compiled anew, which, however, quickly disintegrated. Even the famous story of Sindbad was not included in all versions of the collection. As a rule, only fragments of the collection were likely to have been in circulation, which were then individually combined with other stories to form a new, complete collection of the Thousand and One Nights . Thus there is no closed original text for A Thousand and One Nights with a defined author, collector or editor . Rather, it is an open collection with various editors influenced by the oral storytelling tradition of the Orient. New compilations can be traced back to the end of the 18th century. One of the last is the Egyptian Review (ZÄR), recognized as such by the French orientalist H. Zotenberg, from which some manuscripts reached Europe soon after 1800, and others. a. by Joseph von Hammer, who made a French translation in Constantinople in 1806, but it was never printed (German translation by Zinserling, see below). The manuscripts of this review were also the templates for the printed editions of Boulaq 1835 and Calcutta 1839–1842, the text of which was considered to be the authentic text for a long time because of its quality and (apparent) completeness.

The oldest surviving Arabic text is the Galland manuscript , which was created around 1450 at the earliest. It is a torso that breaks off in the middle of the 282nd night, named after the French orientalist Antoine Galland (1646–1715), who acquired this manuscript in 1701. From 1704 Galland published a French adaptation of the collection of stories and thus initiated the European reception of the Arabian Nights . For the person of Scheherazade, he was inspired by Madame d'Aulnoy and the Marquise d'O , a lady-in-waiting of the Duchess of Burgundy . After his death in 1715, the manuscript came into the possession of the Bibliothèque du Roi , today's French National Library .

After Galland began to receive the Orient in Europe, the paradoxical process arose that European compilations (including the "defusing" adaptations) were translated back into Arabic and thus influenced the Arabic tradition itself. In 2010 the orientalist Claudia Ott announced that she had discovered a previously unknown Arabic manuscript in the Tübingen university library, probably from the period around 1600, which begins in a practically immediate continuation of the Galland manuscript with the 283rd night and lasts until the 542nd night. In 2010 Claudia Ott also discovered the oldest surviving compilation of the Scheherazad stories in the Aga Khan Museum in Andalusia: One Hundred and One Nights , the little sister of the large collection of stories that arose in Magreb and Moorish Andalusia . It dates from 1234.

content

Schahriyâr, king of an unnamed island "between India and the Empire of China", is so shocked by his wife's infidelity that he has her killed and instructs his vizier to give him a new virgin every - in some versions: every third - night from now on who is also killed the next morning.

After a while, Scheherazade , the vizier's daughter, wants to become the king's wife in order to end the killing. She starts telling him stories; at the end of the night it has reached such an exciting point that the king desperately wants to hear the continuation and postpones the execution. The following night Scheherazade continues the story, interrupting again in the morning at an exciting point, etc. After a thousand and one nights she gave birth to three children in the oriental print version, and the king grants her mercy.

In the final version of the printed edition Breslau 1824–1843, also from the Orient, it showed the king the injustice of his actions and "converted" him; he thanks God for sending him Scheherazade and celebrates a proper wedding with her; Children do not appear in this version. This conclusion can also be found in Habicht's German translation (Breslau 1824).

Galland had no draft text for his rather simple form of the conclusion, but all in all it corresponds most closely to that of the Breslau print: the king admires Scheherazade, inwardly moves away from his oath to have his wife killed after the wedding night and grants her mercy . In a letter from 1702, however, he already sketches this end of the Arabian Nights , which he must have known from his friends, who first informed him of the existence of the collection.

Shape description

The stories are very different; there are historical tales, anecdotes , love stories, tragedies , comedies , poems , burlesques and religious legends . Historically documented characters also play a role in some stories, such as the caliph Hārūn ar-Raschīd . Often the stories are linked on several levels. The style of speech is often very flowery and uses rhyming prose in some places .

History of translation and impact

In Europe , the Arabian Nights is often falsely equated with fairy tales for children, which in no way does justice to the role of the original as a story collection for adults with sometimes very erotic stories. The reason for this misunderstanding is probably the first European translation by the French orientalist Antoine Galland , who translated the stories 1704–1708 and thereby defused or erased the religious and erotic components of the original. Galland also added some stories that did not exist in his Arabic templates to his translation, e.g. B. Sindbad the Navigator , based on a stand-alone copy that he had already translated before he found out about the existence of the Arabian Nights collection , or Aladin and the magic lamp and Ali Baba and the 40 robbers that he had in Paris in 1709 Hanna Diyab , a storyteller from Syria , had heard. Hanna Diyab was a Maronite Christian from Aleppo, Syria, who traveled to Paris with a French trader. The publication of Galland had an unexpectedly large impact.

August Ernst Zinserling translated the text after the French translation by Joseph von Hammer into German (Stuttgart and Tübingen 1823-1824).

Max Habicht together with Friedrich Heinrich von der Hagen and Karl Schall (Breslau 1825) provided a complete translation based on the translation by Galland (“For the first time supplemented and completely translated from a Tunisian manuscript” ). The first German translation from original Arabic texts was made by the orientalist Gustav Weil . It was published 1837–1841 and was only true to the work cum grano salis : the poetry and rhyming prose parts were not true to form, the repertoire came from a selection of different versions. The first true-to-original translation comes from Richard Francis Burton , who published the stories in 16 volumes from 1885–1888 under the title The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night , causing a scandal in Victorian England . Based on the Burton translation, a German translation was created by Felix Paul Greve .

An edition published in Vienna between 1906 and 1914, first published by Cary von Karwath and later by Adolf Neumann, was also based on Burton's translation. On the title page, the 18-volume transmission was described as a "complete and in no way abbreviated (or censored) edition based on the oriental texts", but it was not only based on the Arabic original text, as were all previously published German translations, but followed in the erotic text passages, as well as in the title ("The Book of a Thousand Nights and One Night"), clearly the model of Burton. The erotically illustrated and bibliophile edition of 520 copies, intended only for subscribers , caused a scandal soon after its publication in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and in the German Reich because of the revealing text passages and the illustrations created by Franz von Bayros , Raphael Kirchner and others. The edition's illustrations - e.g. Some of the entire volumes were indexed and confiscated by the authorities.

Gustav Weil's translation appeared from 1837 (completely revised in 1865) and was based on the texts of the first Bulak edition from 1835 and the Breslau edition. Max Henning obtained another German translation for the Reclams Universal Library in 24 volumes. It appeared from 1896 and was based on a later Bulak edition and a selection of other editions and sources.

In 1918 the Tübingen orientalist Enno Littmann was commissioned by Insel Verlag to revise Greve's translation. However, he decided on an almost complete new translation, which he based on the edited Arabic edition from 1839–1842 (Calcutta II) printed in India.

The first translation from the Arabic text of the Wortley Montagu manuscript, a collection that originated in Egypt in 1764 and was brought to the Oxford Bodleian Library a little later, was done by Felix Tauer . It is viewed as a supplement to Littman's transmission.

Mahmud Tarshuna, a Tunisian Arabist, publishes Mi'at layla wa-layla on the basis of six Arabic manuscripts from the 18th and 19th centuries.

The Arabist and Islamic scholar Muhsin Mahdi , born in 1926, presented a critical edition of the Galland manuscript in 1984 after twenty-five years of work . The text of the oldest surviving Arabic version is now available in its original form. In 2004 the Arabist Claudia Ott published a German translation of this edition for the first time. Their goal was a transmission true to the text right down to the sound shape and metrics . During this time, Otto Kallscheuer emphasized her “clear, lively German” and that she did without “orientalizing embellishments”.

expenditure

(in chronological order)

Arabic text

- Calcutta I : The Arabian Nights Entertainments. In the Original Arabic. Published under the Patronage of the College of Fort William, by Shuekh Uhmud bin Moohummud Shirwanee ool Yumunee. Two volumes. Calcutta 1814-1818 ( Volume 1 ).

- Bulak edition : Kitâb alf laila wa-laila. Two volumes. Bulaq (Cairo) 1835. (First non-European edition. The text is based on a linguistically edited manuscript of the Egyptian Review [ZER] , which was recognized by Hermann Zotenberg and was compiled around 1775. Further editions appeared in the following years.)

- Calcutta II : The Alif Laila or Book of the Thousand Nights and one Night, Commonly known as "The Arabian Nights Entertainments". Now, for the first time, published complete in the original Arabic, from an Egyptian manuscript brought to India by the late Major Turner. Edited by WH Macnaghten, Esq. Four volumes. Calcutta 1839–1842.

- Breslauer or Habicht edition : A thousand and one nights Arabic. After a manuscript from Tunis, edited by Maximilian Habicht . After his death, continued by M. Heinrich Leberecht Fleischer. Six volumes. Breslau 1825–1843.

German translations

- Thousand and one Night. Arabic stories for the first time faithfully translated from the original Arabic text by Gustav Weil . With 2000 pictures and vignettes by F. Groß. Edited and with a porch by August Lewald . Four volumes. Verlag der Classiker, Stuttgart and Pforzheim 1839–1841.

- Thousand and one Night. Translated from the Arabic by Max Henning. 24 volumes. Reclam, Leipzig 1896-1900.

- The book of a thousand nights and one night. Complete and in no way abridged edition based on the existing oriental texts, obtained from Cary von Karwath ; with illustrations by Choisy Le Conin (that is Franz von Bayros ). 18 volumes. CW Stern Verlag, Vienna 1906–1913; Reprinted (reduced) in: Bibliotheca Historica , 2013.

- The stories from the thousand and one nights. Complete German edition in twelve volumes based on the Burton 's English edition obtained from Felix Paul Greve . Twelve volumes. Insel, Leipzig 1907–1908; also in: Digitale Bibliothek , Volume 87. Directmedia , Berlin 2003 (new edition in electronic form). ISBN 3-89853-187-2 .

- The stories from the thousand and one nights . Complete German edition in six volumes. Based on the Arabic original text of the Calcutta edition from 1839. Transferred by Enno Littmann . Insel, Wiesbaden and Frankfurt am Main 1953 and 1976; again Komet, Frechen 2000. ISBN 3-89836-308-2 .

- The stories from the thousand and one nights . The stories of the Wortley Montague manuscript of the Oxford Bodleian Library not contained in other versions of Thousand and One Nights , completely transferred from the Arabic original and explained by Felix Tauer , Insel-Verlag, Leipzig 1983.

- Tales of the Schehersâd from the Thousand and One Nights . German by Max Henning , in: Pocket Library of World Literature , Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin and Weimar 1983.

- Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall (ed.): Fairy tales from a hundred and one nights (= The Other Library , Volume 15). Greno, Nördlingen 1986. ISBN 3-921568-72-2 .

-

A thousand and one nights . Translated by Claudia Ott . Tenth revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2009 (based on the oldest known Arabic manuscript in the edition by Muhsin Mahdi : Alf laila wa-laila ). ISBN 3-406-51680-7 .

- Complete audio book edition: Hörbuchverlag , Hamburg 2004, 24 CDs, read by Heikko Deutschmann , Marlen Diekhoff , Eva Mattes , Katja Riemann , Charlotte Schwab , Elisabeth Schwarz . ISBN 978-3-89903-789-0 .

- Claudia Ott (translator): 101 night. Translated from Arabic into German for the first time by Claudia Ott based on the handwriting of the Aga Khan Museum. Manesse, Zurich 2012 (based on the oldest manuscript from Andalusia from 1234. Also contains previously unknown stories). ISBN 3-7175-9026-X .

- Claudia Ott (translator): A thousand and one nights. The happy ending. After the handwriting of the Rasit Efendi Library Kayseri, first translated into German by Claudia Ott. CH Beck Munich 2016. ISBN 978-3-406-68826-3

reception

Fictional literature

Various writers wrote sequels or more or less strongly based narratives, including:

- Théophile Gautier : La Mille et Deuxième Nuit ( story , 1842; German "The thousand and second nights")

- Edgar Allan Poe : The Thousand-and-Second Tale of Scheherazade ( short story , 1845; German "The Thousand and Two Nights of Scheherazade")

- Jules Verne : La Mille et Deuxième Nuit ( Opéra-comique , around 1850)

- Hugo von Hofmannsthal : The fairy tale of the 672nd night (story, 1895)

- Franz Hessel : The porter of Baghdad (story, 1933)

- Joseph Roth : The Story of the 1002nd Nights ( novel , 1939)

- Klaus Kordon : The Thousand and Two Nights and the Day After ( children's book , 1985)

Movie

- The silhouette film The Adventures of Prince Achmed by Lotte Reiniger (1926) is based on the stories from the Arabian Nights .

- Arabian Nights (1942), USA

- The 1945 film 1001 Nights is based on Aladin and the Magic Lamp

- Aladdin's Adventures (1961), Italy

- Aladdin's magic lamp (1966), USSR

- A Thousand and One Nights (1968) Adventure Comedy, I / E Original Title: Sharaz

- Aladin and the Magic Lamp (1969), French cartoon

- In 1974 Pier Paolo Pasolini filmed some key episodes under the title Il fiore delle mille e una notte (German: Erotic Stories from 1001 Nights )

- Aladdin (1986), Italy / France

- In 1992, the Disney film Aladdin emerged from the story Aladin and the Magic Lamp

- In 2000, the story of Scheherazade resulted in the film Arabian Nights - Adventures from 1001 Nights

- Ali Baba and the 40 thieves (2007) , France

- Miguel Gomez adapts the story in his trilogy "1001 Nights" into the parts "Volume 1: The Restless", "Volume 2: The Desperate" and "Volume 3: The Delighted" ( As Mil e Uma Noites : O Inquieto , O Desolado and O Encantado )

Opera

- The Caliph of Baghdad , comic opera by François-Adrien Boieldieu (music) and Claude Godard d'Aucour de Saint-Just (text), premiered Paris September 16, 1800

- Abu Hassan , Komische Oper by Carl Maria von Weber (music) and Franz Carl Hiemer (text), premiered in Munich , June 4, 1811

- Aladin or The Magic Lamp , opera by Nicolas Isouard (music) and Charles Guillaume Étienne (text), premiered in Paris , 6 February 1822

- Ali Baba or The Forty Robbers , opera by Luigi Cherubini (music) and Eugène Scribe and Anne Honoré Joseph Duveyrier, called Mélesville (text), use of the music from the opera Koukourgi , not listed , premiered in Paris , July 22, 1833

- The Barber of Baghdad , Komische Oper by Peter Cornelius (music and text), UA Weimar , December 15, 1858

- Ali Baba , opera by Giovanni Bottesini (music), world premiere in London , 1871

- Aladdin , opera by Christian Frederik Hornemann (music) and Benjamin Johan Feddersen (text), UA Copenhagen , 1888

- Sindbad , opera by Frederick Shepherd Converse (music), WP 1913

- Scheherazade , opera by Bernhard Sekles (music) and Gerdt von Bassewitz (text), premiere Mannheim , November 2, 1917

- Bright nights . Opera by Helmut Krausser (text) and Moritz Eggert (music), premier Munich , Munich Biennale 1997

- alf laila wa laila . Opera festival by sirene opera theater with 12 short operas based on stories from 1001 nights; Kristine Tornquist (text) and Akos Banlaky , René Clemencic , François-Pierre Descamps , Jury Everhartz , Lukas Haselböck , Paul Koutnik , Matthias Kranebitter , Kurt Schwertsik , Willi Spuller , Oliver Weber , Robert M Wildling (music), UA Vienna , Expedithalle der former anchor factory 2011

- Ali Baba and the 40 Robbers , children's opera by Taner Akyol (music) and Cetin Ipekkaya and Marietta Rohrer-Ipekkaya (text), premiered Berlin , October 28, 2012

operetta

- Indigo and the forty robbers , operetta by Johann Strauss (son) (music), premiered in Vienna , February 10, 1871

- Thousand and one nights , operetta by Johann Strauss (son) (music) and Leo Stein and Karl Lindau (text), new version of “Indigo and the forty thieves” by Ernst Reiterer , UA Vienna , October 27, 1907

music

- Scheherazade , symphonic poem by Nikolai Rimski-Korsakow , 1888

musical

- Scheherazade , musical by Vlastimil Hála (music) and Vratislav Blažek (text), UA Hradec Králové (Königgrätz) , 1967

ballet

- 1001 Notsch (1001 ночь). Ballet by Fikrət Əmirov (first performance: 1979 in Baku )

theatre

- Erotic and comical stories from 1001 nights , play by the Markus Zohner Theater Compagnie with Patrizia Barbuiani and Markus Zohner

- Thousand and One Nights , play by Barbara Hass with music by Nikolai Rimski-Korsakow for children from the age of five (Theater for Children, Hamburg)

radio play

- Helma Sanders-Brahms : A thousand and one nights. 1st to 14th night . With Eva Mattes , Dieter Mann , Ulrich Matthes u. a. Music: Günter "Baby" Sommer . Directors: Robert Matejka (1-12) and Helma Sanders-Brahms (13-14). Production: RIAS (later: DLR Berlin), 1993–2001. (CD edition: Der Hörverlag, 2005. ISBN 3-89940-647-8 ; awarded the Corine Audiobook Prize 2005.)

- Helma Sanders-Brahms: A thousand and one nights. 15th to 17th night . Director: Helma Sanders-Brahms. Production: DLR Berlin, 2002.

Others

- The nomenclature of the topography of the Saturn moon Enceladus is named after places and characters from the stories of the Arabian Nights.

Research literature

(in chronological order)

- Adolf Gelber: 1001 nights. The meaning of the Scheherazade stories . M. Perles, Vienna 1917.

- Stefan Zweig : The drama in a thousand and one nights. In: Reviews 1902–1939. Encounters with books . 1983 E-Text Gutenberg-DE .

- Heinz Grotzfeld: Neglected Conclusions of the Arabian Nights: Gleanings in Forgotten and Overlooked Recensions . In: Journal of Arabic Literature. Berlin 1985, 16. ISSN 0030-5383 .

- Johannes Merkel (Ed.): One of a thousand nights. Fairy tales from the Orient . Weismann, Munich 1987, 1994. ISBN 3-88897-030-X .

- Walther Wiebke: A thousand and one nights . Artemis, Munich / Zurich 1987. ISBN 3-7608-1331-3 .

- Abdelfattah Kilito: Which is the Arab book? In: Islam, Democracy, Modernity. CH Beck, Munich 1998. ISBN 3-406-43349-9

- Robert Irwin: The World of a Thousand and One Nights . Insel, Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 1997, 2004. ISBN 3-458-16879-6 .

- Walther Wiebke: The little history of Arabic literature. From pre-Islamic times to the present . Beck, Munich 2004. ISBN 3-406-52243-2 .

- Katharina Mommsen: Goethe and 1001 Nights . Bonn 2006. ISBN 3-9809762-9-7 .

- Hedwig Appelt: The fabulous world of a thousand and one nights . Theiss, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8062-2305-7 .

Web links

- Interview with Claudia Ott: New chapter in Arabic literary history - Manuscript of 101 Nights discovered

- English translation by Burton and other English editions

- A thousand and one nights in the Gutenberg-DE project

- The stories of the 1001 nights from Tunisia - Arabic stories ( Memento from April 30, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- Fairy tales from 1001 nights in the literature network

- Ali Baba and the 40 thieves as a free audio book ( memento from October 22, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) at Vorleser.net

- Stories from 1001 Nights (selection) - edited text

-

A Thousand and One Nights Public Domain Audiobook at LibriVox

A Thousand and One Nights Public Domain Audiobook at LibriVox

See also

- A thousand and one days , an extensive collection of Persian fairy tales

- The magic carpet is an element of several fairy tales from the Arabian Nights.

- Solomon

- Turandot

Individual evidence

- ↑ A thousand and one nights timeline

- ^ Jacob W. Grimm: Selected Tales. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth 1982, ISBN 0-14-044401-7 , p. 19.

- ↑ Jack David Zipes, Richard Francis Burton: The Arabian Nights. The Marvels and Wonders of the Thousand and One Nights. Signet Classic, New York 1991, ISBN 0-451-52542-6 , p. 585.

- ^ Jürgen Leonhardt : Latin: History of a world language. CH Beck, 2009. ISBN 978-3-406-56898-5 . P. 180. Online partial view

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Rachel Schnold, Victor Bochman: The Jews and "The Arabian Nights" . In: Ministry of Foreign Affairs (ed.): ARIEL . The Israel Review of Arts and Letters. tape 103 , 1996, ISSN 0004-1343 , ZDB -ID 1500482-X (English, mfa.gov.il [accessed on July 20, 2014]).

- ↑ a b Always new nights. In: The time. No. 24, June 10, 2010.

- ↑ Manuscript AKM 00513. Website of the book edition m. Introductory video

- ↑ A. Gelber, however, advocates the thesis that the order of the stories follows a well thought-out dramatic structure. Of course, it remains unclear how long this will to form would have to have influenced the design.

- ^ Hanna Diyab: From Aleppo to Paris . In: Christian Döring (Ed.): The other library . The Other Library, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-8477-0378-5 , pp. 489 .

- ↑ Enno Littmann: 1001 nights. Volume 6. Insel Verlag, Wiesbaden 1953, p. 649.

- ↑ [2] , Maḥmūd Ṭaršūna: Miʾat layla wa-layla. Tunis 1979.

- ↑ A Thousand and One Nights - the unknown original , ( Memento August 4, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Website for the book.

- ↑ Summarized reviews of the translation by Claudia Otts from NZZ, FR, SZ, Zeit, taz and FAZ. In: Perlentaucher.de

- ↑ Dawn B. Sova: Critical Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. A Literary Reference to His Life and Work . Facts on File / Infobase, New York 2007, p. 177 f. ( online ).

- ↑ Jules Verne: Scheherazade's Last Night and Other Plays . First English Translation. North American Jules Verne Society / BearManor Media, Albany / GA 2018 ( online ).

- ↑ A thousand and one nights. Internet Movie Database , accessed May 22, 2015 .

- ↑ 1001 Notsch on Klassika