Opéra-comique (type of work)

The Opéra-Comique is a genus of opera in Paris of the 17th century from the suburban comedy with musical interludes ( Vaudeville originated) and up in the 19th century existed. It is characterized by the fact that the musical numbers are not connected by sung recitatives , but by spoken dialogues . Counterparts to this are the Singspiel or Spieloper in the German-speaking area and the Ballad Opera in English .

The works, which are included in the Opéra-comique, offer a colorful picture in terms of designation, form, content and number of acts . What they have in common, however, is that there are no lyrical gods in it, as in the tragedy . Their heroes are usually not nobles either.

In the course of time, the Opéra-comique experienced stylistic changes. Around the middle of the 19th century it split into two directions: one that approached the operetta and another that increasingly made use of the means of the grand opéra , until it was no longer possible to distinguish it from it.

term

Whether a work is comic or tragic is irrelevant for the genre Opéra-comique. The plot is often touchingly sentimental. The name comique stems from the fact that up to the 18th century the tragedy was reserved for the nobility (see class clause ) and the rising bourgeoisie had to be content with comedies .

Although influenced by Italy, the Opéra-comique replaced Italian, which the bourgeoisie was not familiar with, with the national language, which also applies to the German Singspiel . Since large parts were spoken, the roles could also be taken over by singing actors, and not just by (Italian) singing virtuosos.

Because the court theater remained in some German-speaking residences until 1918, even if it was increasingly opened to the bourgeoisie, the opéra-comique remained here in the 19th century as a bourgeois alternative to court opera. Traveling theaters, which still existed, and privately owned theaters (such as the Theater an der Wien or the Königsstädtische Theater ) were the original and main venues for this genre. This is illustrated by Albert Lortzing's Singspiele, most radically the "Freedom Opera " Regina from 1848. In Paris, on the other hand, the staid bourgeois opéra-comique of the 18th century changed after the Napoleonic theater reform in the wake of the French Revolution to the glamorous metropolitan area of the 19th century .

18th century

Fair theater

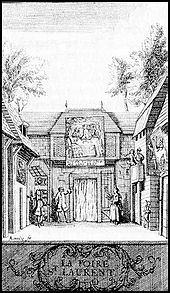

The Parisian fair theater had known comedies with inserted songs ( vaudevilles ) since the 17th century . They competed with the performances of Italian troops and attracted increasing attention from the bourgeoisie. Alain Lesage's opera parody Télémaque was one of the first pieces to be called Opéra-comique around 1715. In the vaudevilles, familiar melodies were underlaid with new texts, in the opéra-comique, on the other hand, the music was also newly composed. Often these pieces were called "comédie mêlée d'ariettes" ("comedy mixed with small arias") or "drame mêlé de chants" ("drama mixed with chants"), which indicates the mixture of spoken text and song.

Buffonist dispute

The rivalry between Italian and French music was always reignited. When an Italian opera troupe celebrated success in Paris in 1752, the philosopher and composer Jean-Jacques Rousseau presented his intermède Le devin du village ( The Village Fortune Teller ), an opera comique that, with the help of the court, could compete with the Italians. Rousseau, who was happy about the success but did not want to belong to the conservative “French” party, instigated the Querelle des bouffons ( Buffonist dispute ) in the following year with the Lettre sur la musique française ( letter on French music ) flatly condemned French opera music and raised the Italian opera buffa to heaven.

Like their Italian models, especially Pergolesi's Serva padrona , written in 1733, Rousseau's short opera is about the success of simple people, but comedy and intrigue have been withdrawn in favor of constructive, positive plot elements (see Rührstück ). Although Rousseau sought French recitatives , his example did not catch on : In the Opéra-comique, the spoken text of the fairground comedies remained. But the simple, sentimental tone pointed the way to the “serious” pieces of this genre.

Recognition and permanent venue

Thus, after the middle of the century, the opéra-comique became the bourgeois alternative to the courtly tragedy lyrique on the one hand and vulgar vaudeville on the other. Composers like François-André Danican Philidor or Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny developed their musical means. The poet Charles-Simon Favart boasted that, with the Opéra-comique, he had created an opera for the “honnêtes gens” (“honorable people”). He worked with the composers Egidio Duni and Antoine Dauvergne . The new building of the Comédie-Italienne - the home of the Opéra-comique - inaugurated in 1783 was named Salle Favart after him .

The composer Nicolas Dalayrac represented a lighter, comedy-like variety of Opéra-comique. His singing roles could often still be mastered by actors. André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry, on the other hand, is considered to be the pioneer of the more modern, more dramatic and musically more weighty opera comique. His best-known work, Zémire et Azor from 1771, has been described as the point of no return on the path of the former fair, spectacular Opéra-comique, to respectability . In his Richard Cœur de Lion ( Richard the Lionheart ) of 1784 a patriotic melody recurs several times - a preliminary form of the leitmotif . The composers who created opéras-comiques during the French Revolution include, in addition to Grétry and his Guillaume Tell ( Wilhelm Tell ) from 1791, Étienne-Nicolas Méhul , Nicolas Isouard and François Devienne .

Effect in the German-speaking area

Opéra-comique was admired and imitated in the German-speaking region, but its joke was often not understood. Marie Duronceray's Les amours de Bastien et Bastienne (1753), a biting parody of Rousseau's Devin du village , mutated again into a staid, touching singspiel in the German version of Bastien und Bastienne (1768) set by Mozart . Sentimental works were better understood. Since the French Revolution , it was fashionable that the everyday problems of ordinary people should be taken seriously and not laughed at. Méhuls Joseph (1807), for example, was played frequently and was the model for operas similar to Joseph Weigl's Die Schweizer Familie (1809). Nicolas Dalayrac's Nina or Madness from Love ( Nina ou la folie par amour , 1786), Die Wilden ( Azémia ou le nouveau Robinson , 1787), The two Savoyards ( Les deux petits savoyards , 1789) or Adolph and Clara ( Adolphe et Clara ou les deux prisonniers , 1799) were popular in the German-speaking area for decades.

Such older opéras comiques formed an inexhaustible reservoir for translations, adaptations and new settings well into the 19th century. The German touring theaters always had opéras comiques in their repertoire , which could be performed with relatively little effort. The first Viennese operetta , Suppés Pensionat from 1860, also goes back to an older Opéra-comique. However, a nationalist-oriented music historiography tried to pass off the German operas as original works.

The music theater of continental Europe was largely determined by Paris as the culturally leading metropolis . So wrote Gluck as conductor of the French Theater ( Burgtheater ) in Vienna 1758-1763 on French librettos several Opéras-comiques before the mentioned house (temporarily) the German Singspiel turned. Even if the last-mentioned experiment was seen as a “national” triumph in the 19th century - apart from the Abduction from the Seraglio (1782), nothing lasting came about in this context. The founding of the new privately owned theaters such as the Leopoldstädter Theater in 1781 and the Freihausheater in 1787 (in which Mozart's Magic Flute was premiered in 1791 ) shifted such singspiele from the courtly stage to the "bourgeois" stages in Vienna.

19th century

Reorientation

The emancipation of the opéra-comique was complete when, after the revolution, it was able to take the place of courtly tragedy. Luigi Cherubini's tragic opera Médée ( Medea ) from 1797 belongs to opéra-comique of this kind . In connection with theatrical melodrama, more modern types emerged, such as the rescue opera with its adventure material, which Henri Montan Berton used for example .

A troubled era of experimentation was during Napoleon's reign . In Beethoven's Fidelio (1805–1814), the first act is largely based on the older opera-comique, while the composer then goes with the spectacular Liberation Quartet to the rescue opera area to end the work in the large choir like a final oratorio .

The more modern “ spectacle pieces ” from France also had a considerable influence on so-called romantic opera , such as Carl Maria von Weber's Freischütz (1821), which, as an opera with a bourgeois subject and spoken dialogues, was one of the opéra-comiques of that time.

The names of the composers François-Adrien Boïeldieu and Daniel-François-Esprit Auber as well as the librettist Eugène Scribe are associated with the tradition of this younger and larger opéra-comique . Boïeldieu's La dame blanche from 1825 reinstated the aristocratic society in its old law and was thus in the service of the restoration . Aubers Le maçon ( The Mason ) from the same year, however, deals with the fate of craftsmen.

Profiling it from the Grand Opéra

In the 1827/28 season, when the melodrama poet and producer René Charles Guilbert de Pixérécourt was the director of the Opéra-Comique, the variants of the Parisian musical theater were closer than ever before, and the grand opéra split up as the successor to the old-fashioned one Wear the lyrique. The political importance of the opéra-comique only occasionally came to fruition and passed over to the grand opéra, as in Auber's La muette de Portici (1828), the performance of which on August 25, 1830 in Brussels sparked the Belgian Revolution . Although this piece is now counted as part of the grand opéra due to the five acts and the recitatives, it retained the characteristics of the opéra-comique with the integrated pantomime role and the socially low-ranking main characters.

During the pre- March period, people preferred entertaining works that were not offensive anywhere. They developed musical stylistic devices that made Gioachino Rossini famous. Aubers Fra Diavolo (1830) and Donizetti's La fille du régiment (1840) are among the most successful operas in this genre and remained in the repertoire for a hundred years.

In Adolphe Adams Le postillon de Lonjumeau ( Der Postillon von Lonjumeau ) from 1836, which was also successful in the German-speaking area, the tendency of the older opéra-comique towards the sentimental is again very clear: the alleged bigamy of the main character turns out to be loyalty because The second wife of the postilion, who has become a singing star, turns out to be his abandoned first: So he does not lead a lotter life, but is basically a dutiful citizen.

The grand opéra (which was based at the Paris Opera ), with its main representative Giacomo Meyerbeer , became the representative upper-class opera genre . Meyerbeer tried to turn Opéra-comique with his military camp in Silesia (Berlin 1844) into a representative aristocratic opera, but met with resistance in the German-speaking theater world. In Paris, the work was only able to gain a foothold in the French revision L'étoile du nord ( The Polar Star ) of 1854.

The opéra-comique was struggling to make a name for itself and emulated the grand opéra. With his artist drama Benvenuto Cellini (1838), Hector Berlioz was tied between opéra-comique and grand opéra. Opéra-comique could no longer present itself as an alternative to courtly opera and was no longer the “cheerful” genre.

Differentiation from the operetta

With the modern vaudevilles of the boulevard theaters and later with the music hall attractions, a kind of music theater for servants and workers emerged, so that the opéra-comique, like the grand opéra, represented the upper class.

The composer Jacques Offenbach criticized this and stated in a treatise from 1856 that he wanted to revive the “simple and true” Opéra-Comique of the 18th century, because the pieces played in the House of Opéra-Comique have now become “little grand opéras” . The result was Offenbach's Paris operetta at the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens . Offenbach's work Barkouf (1860) with a dog as the main character, performed at the Opéra-Comique, fell through. The grotesquely funny pieces had no future in this place. There were still serene works in this genre, for example those by Victor Massé .

Carmen and recent successes

The larger-scale Opéra-comique was able to hold up because the Grand Opéra seemed exhausted after Meyerbeer's death in 1864. Mignon by Ambroise Thomas (1866) after Wilhelm Meister's apprenticeship years , after Faust and Werther, again showed how well Goethe's fictional characters did on the French opera stage. With Bizet's Carmen (1875), the opéra-comique again became the leading genre of French music theater. The tradition that it was the opera of the "common people" and that it could also depict tragic fates in this milieu was taken up with Carmen . The fact that the protagonist doesn't care about civil values led to a scandal at the premiere.

Because the singing parts of actors were no longer manageable and singers had trouble with the spoken dialogues, but also because the denomination of the music was no longer considered appropriate to the opera, many opéras comiques were retrospectively provided with recitatives. Carmen shared this fate with Gounod's Faust from 1859 and Offenbach's Contes d'Hoffmann ( Hoffmann's Tales ) from 1881, which are counted among the last significant works of the genre.

With the urge for well- composed form , the opéra-comique gradually disappeared, around the same time that the Singspiel or the game opera had to give way to musical drama as a “high” and Viennese operetta as a “lower” genre.

Composers and works (selection)

-

François-André Danican Philidor (1726–1795):

- Tom Jones, Paris 1765.

-

Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny (1729-1817):

- Le roi et le fermier ( The King and the Tenant ), Paris 1762.

- Rose et Colas, Paris 1764.

- Le déserteur ( The Deserter ), Paris 1769.

-

André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry (1741–1813):

- Lucile, Paris 1769.

- Zémire et Azor , Fontainebleau 1771.

- L'amant jaloux ( The Jealous Lover ), Versailles 1778.

- Richard Cœur de Lion ( Richard the Lionheart ), Paris 1784.

- L'épreuve villageoise ( The Village Trial ), Versailles 1784.

- Guillaume Tell ( Wilhelm Tell ), Paris 1791.

-

Luigi Cherubini (1760-1842):

- Médée ( Medea ), Paris 1797.

- Les deux journées ( The Water Carrier ), Paris 1800.

-

Étienne-Nicolas Méhul (1763–1817):

- Joseph, Paris 1807.

-

François-Adrien Boïeldieu (1775–1834):

- La dame blanche ( The White Lady ), Paris 1825.

-

Daniel-François-Esprit Auber (1782–1871):

- Fra Diavolo , Paris 1830.

-

Gaetano Donizetti (1797–1848):

- La fille du régiment ( The Regiment's Daughter ), Paris 1840.

-

Adolphe Adam (1803-1856):

- Le postillon de Lonjumeau ( The Postillon of Lonjumeau ), Paris 1836.

- Si jétais roi ( If I were King ), Paris 1852.

-

Hector Berlioz (1803–1869):

- Benvenuto Cellini (1st version), Paris 1838.

- Béatrice et Bénédict, Baden-Baden 1862.

-

Ambroise Thomas (1811-1896):

- Mignon , Paris 1866.

-

Charles Gounod (1818-1893):

- Le médecin malgré lui ( The unwilling doctor ), Paris 1858.

- Faust (1st version), Paris 1859.

-

Jacques Offenbach (1819–1880):

- Les contes d'Hoffmann ( Hoffmann's Tales ), Paris 1881.

- Georges Bizet (1838–1875):

See also

literature

- Sieghart Döhring , Sabine Henze-Döhring : Opera and musical drama in the 19th century. Laaber Verlag, Laaber 1997, ISBN 3-89007-136-8 .

- Herbert Schneider, Nicole Wild (Hrsg.): The Opéra comique and its influence on the European music theater in the 19th century. Olms, Hildesheim 1997, ISBN 3-487-10250-1 .

- Thomas Betzwieser : Speaking and Singing. Aesthetics and manifestations of the dialogue opera , JB Metzler, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 978-347-645267-2 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ See David Charlton: Grétry and the growth of opéra-comique. Cambridge University Press , Cambridge 1986, ISBN 978-0-521-25129-7 .

- ↑ Patrick Taïeb, Judith Le Blanc: Merveilleux et réalisme dans "Zémire et Azor": un échange entre Diderot et Grétry. In: Dix-huitème siècle, 2011/1 (No. 43), pp. 185–201 ( digitized version ), here: p. 185.