Geometric patterns in Islamic art

Filling an area decoratively with geometrically constructed patterns is part of the visual arts of many cultures. In Islamic art , this form of ornamentation achieved a special form and perfection. More recently, the ornaments have attracted increased interest from European artists such as MC Escher , mathematicians such as Peter Lu and physicists such as Paul Steinhardt .

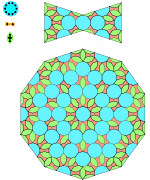

Islamic geometric patterns are made up of repetitive polygonal or circular surfaces that overlap or are intertwined to form complex patterns, often in the form of mathematical tiling . Over time, the geometric constructions became more and more complex. They can stand alone as a decorative ornament, a frame for other (floral or calligraphic) ornaments, or fill in the background.

Together with the arabesque , a flat, stylized tendril ornament made of forked leaves in swinging motion, and calligraphic inscriptions, geometric patterns are characteristic of Islamic art. It is typical for this that the patterns and ornaments, once developed and understood in their construction, were used to decorate different objects. In great variety to geometric elements found in Islamic architecture , as Persian in patterns girih tiles , Moroccan Zellij -Kachelwerk, the architectural elements of the Muqarnas the west of the Islamic world and the Indian Jali , but also in the ceramic art, book covers embossed leather, carved in wood, on metal, and in fabrics, woven fabrics, carpets and flat woven fabrics .

The modern discussion as to whether or not all 17 known mathematical ornament groups appear in the Alhambra shows how far the ingenuity of Islamic artists explored the limits of what is mathematically possible even according to modern understanding in the 15th century.

origin

Parts of the later Islamic world such as Anatolia , Egypt and Syria have been in existence since the 1st century BC. Ruled by the Roman Empire , later by the Byzantine Empire . The Eastern Roman and Sassanid empires coexisted for over 400 years. In the field of art, both empires have developed similar styles and decorative vocabulary, as exemplified in the mosaics and architecture of Roman Antioch .

According to the strict interpretation of the Islamic ban on images , the visual representation of people or animals is not permitted. Since the codification of the Koran by ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān in the year 651 AD / AH 19 and the reforms of the Umayyad caliph ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān , Islamic art has focused particularly on decorative writing and ornament , even if numerous works of art show that this Ban on images was not consistently observed.

Principles

symmetry

Symmetry is an expression and fundamental tool used by the human mind to process information. From a wide range of possible symmetries, each cultural group selects a number with the help of which it deals with information and preserves it.

In the pattern formation of Islamic ornament, the mirror symmetry is particularly important, both in the composition of the entire surface, as well as an individual ornament. Simple geometric elements such as the square have mirror symmetry in both the horizontal and vertical axes. The isosceles triangle, in mirror or rotational symmetry, or the cross are simple shapes that comply with the laws of symmetry. More complex motifs, such as the arch pattern of the muqarnas , can be understood as a further development of the rule of symmetry. Motifs such as human or animal figures can only be brought into harmony with the rule of symmetry if they are presented in an abstract form, stylized. In this case, mirror symmetry is often reintroduced by doubling the motif, for example in the form of opposing animal ornaments. Davies explains the rules of symmetry in detail using the Anatolian kilim as an example .

Self-complementing (reciprocal) patterns

Usually a pattern is seen in a context, for example on a background. A self-complementing (reciprocal) pattern is more complex, its predominance over the background is canceled. An ornament can alternately become more prominent, or optically fade into the background, from which a new pattern develops at the same time, depending on how the viewer aligns his perception. Simple examples of self-complementing patterns are border patterns such as meanders , self- complementing “battlements” or “arrow” patterns. Self-complementing patterns are experienced as dynamic, as the balance of the motifs in the eye of the beholder is constantly changing.

Infinite rapport

Repeating, interconnected geometric patterns can in principle be thought of as continuing into infinity. The surface therefore offers a section of a pattern that continues into infinity. Depending on the size scale used, an area can be filled with a larger or smaller section of the infinite pattern, the pattern thereby appears more detailed or monumental depending on the scale.

Sample construction

The construction of geometric patterns in "Islamic style" follows certain traditionally established rules:

- Structure from basic geometric shapes, derived from them and irregular shapes;

- Visual layering of different pattern levels;

- Structure through emphasis on individual elements and choice of color.

Within these rules, the designing artist or craftsman finds freedom for independent design and innovation, yet the pattern as such remains unmistakably anchored in the tradition of Islamic art. The most important principles are exemplified using a vault gusset from the Darb-e-Imam shrine , Isfahan.

basic forms

Islamic geometric patterns are made up of circles and polygons, some of which overlap and intertwine, and in the play of complex symmetries, mirroring and rotating with respect to one another, fill an area.

The simplest basic geometric patterns are the circle , on the basis of which pentagons , hexagons and octagons can be constructed. Expressed in the form of mathematical tiling , ornament compositions built up from these basic forms can expand infinitely and thus symbolize infinity . They are constructed on grids, all you need is a ruler and compass.

A simple hexagon or octagon pattern is created from a circle, which is divided into sixths or eighths with a compass and ruler. If these are lined up next to one another and one below the other and the spaces in between are filled with suitable rectangular or cross-shaped tiles, the result is a six-pass pattern as in the window from Chirbat al-Mafjar , or a simple parquet pattern of cross-shaped tiles and octagons as on the facade of the palace of Ani in Northwest Anatolia. It takes more effort to divide a circle into five equal sections to construct a pentagon.

Window in Chirbat al-Mafjar , around 740 AD

Palace of Ani with square and octagon / cross ornaments

Inlays (detail) of pentagons around a ten-pointed star, Topkapı Palace , Istanbul

Derived forms

Polygons can be derived from the basic shapes by repeated circular divisions ; this creates ten, twelve or 16-pointed stars that form “visual anchor points” in the center of a pattern or in a row, the spaces between which are filled by identical or irregular shapes. 9 and 11-pointed star patterns are more complicated to construct.

Irregular shapes

In addition to the regular basic shapes, irregular shapes also appear in geometric patterns, where not all angles are the same and all sides are the same length. Often there are dragon shapes or irregular hexagons, where one angle is more acute and two sides longer, or intermediate pieces shaped like a bow tie.

Sample section, scale

|

|

|

|

Left picture : Pattern of girih tiles , based on ten-pointed stars, Darb-e-Imam-Shrine , Isfahan

Right picture : Construction of the pattern in the Darb-e-Imam-Shrine. Yellow line: outline of the vault gusset. Decagon blue, “ bow tie ” red. The bandwork overlaps the flooring below . |

||

An essential principle of Islamic pattern design is the principle of the infinity of the pattern. Geometric patterns made up of repeating elements can be thought of infinitely. Accordingly, only a section of the pattern appears on a given area. Depending on the chosen scale, the same pattern can look very detailed or monumental.

Pattern nesting and self-similarity

Characteristic of Islamic art is the superimposition of different levels of view or image in one and the same ornament. A surface can be divided into larger geometric sections or fields by an underlying geometric pattern. This is often done using a geometrically constructed grid, which is given spatial depth by means of a braided band design . The individual fields are inserted into a superordinate pattern and can in turn contain geometric ornament constructions. This nested pattern formation can have criteria of self-similarity . Depending on the point of view of the observer, the nesting gives rise to different perspectives on a surface: From a greater distance, the architectural composition of a building appears as a whole, as the surfaces come closer, the surfaces are subdivided until the details of the pattern can be seen up close. Occasionally, pattern elements, for example hexagons, also overlap, so that several elements share individual sections.

Main details and colors

One and the same geometric pattern can appear different by emphasizing individual components. The outlines (or “joints” in a tile work) can be designed narrow, so that a mosaic effect is created, or deliberately kept wide, even emphasized by narrow, elongated elements, so that the underlying, larger pattern is emphasized. If the grid is made in the form of braided ribbons , the impression of spatial depth is created.

The color of its elements also has a major influence on the perception of a geometric pattern . Monochrome design or the use of shades of the same color make a pattern look different than when it is designed in different colors.

development

The development of the patterns can best be traced back to the ornamental decorative elements in architecture, since in buildings, in contrast to moving objects, the place of origin is clear and the history of the building is well documented or can be traced on the building itself.

Simple geometric pattern

The earliest surviving examples of geometrically constructed ornaments in Islamic art were found in the winter palace of Chirbat al-Mafjar from the Umayyad period , which still clearly show Roman, Syrian and Persian traditions. The ornaments of this building complex, as well as those of the Mshatta facade from the same era , are regarded as exemplary for the continued existence of pre-Islamic, Roman and Persian patterns in early Islamic art: the geometric floor mosaics were probably made by Syrian craftsmen in the Roman tradition, the stucco sculptures clearly show Persian, some coarser stucco figures also show the influence of Coptic art from Egypt. A window found at the base of a staircase in the palace's bathhouse has a six-pass pattern inscribed in a circle. The carved ornament shows that the window is intended to consist of a single braided band . This form of ornament is taken directly from the ancient Roman pattern tradition.

Further examples of early geometrical patterns of lined-up diamonds on top can be found in the main mosque of Kairouan , Tunisia, and the 9th century Ibn Tulun mosque in Cairo .

Multi-rayed star patterns and irregular elements

The Friday Mosque of Isfahan was built around 1086 with significantly more complicated 5 to 10-pointed girih tiles , heptagons, and irregular hexagons. 9, 11 and 13-rayed girih, which are more complicated to construct, appear in Persia in the 11th century, and 8 and 12-ray rosette patterns can be found in the architectural decorative elements of the Divriği Mosque and other Seljuk buildings in Sivas . The late stage of development is in the 14th century with 14-rayed patterns in the Jama Masjid in Fatehpur Sikri , India (1571–1596) and up to 16-rayed stars in the Alhambra (1338–1390) and the madrasa of the Sultan Hasan Mosque in Cairo (1463).

Bronze door in the madrasa of the Sultan Hasan Mosque , Cairo, 14th century.

Mihrabnic of the Jami Masjid, Fatehpur Sikri, 1571-5

Examples

Book art

In Islamic book art , the development of geometric patterns can be traced: The Koran manuscript of Ibn al-Bawwab from the 11th century still clearly shows the structure of various circular shapes. Later geometric ornaments are also constructed from circular shapes. Although always present, the individual circular shapes take a back seat to the complex overall pattern. A regional design language is created in accordance with the different styles that have developed in the various Islamic countries. The illumination of the crane manuscript by Arghûn Schâh from the 14th century can be clearly assigned to the world of forms of the Egyptian Mamluk Empire. The basis of the construction, usually a multi-rayed star, can be determined by counting the rays of the central star pattern. In the case of the book illumination of 1180, this is an eight-pointed star from which increasingly complex braided band patterns develop radially outwards.

Koran manuscript of Ibn al-Bawwab , Baghdad, around 1000.

Ceramics

Zellij ( Arabic الزليج, DMG az-Zallīǧ ), derived from azulejo, is ceramic jewelry made of glazed terracotta tiles, which are put together from individual pieces in a plaster to form a pattern, and typical of the art of the Islamic West, Morocco and Moorish Spain . Zellij are used to decorate walls, floors and architectural elements such as fountains or basins.

Zellij consist of complex patterns made up of individually shaped, hand-cut tesserae . The underlying star patterns can have up to 48 or 96 rays, mostly due to the geometry, the number of rays can be divided by six. By varying the color and size of the tesserae and the fill patterns inserted between the rays of the star, the possible variations are almost unlimited. The most perfect Zellij can be found in the Alhambra in Granada .

Zellij are still made in the traditional way today and were used, for example, in the Great Mosque of Paris (1926) or - with the help of computer-aided design - to furnish the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca (1996).

Ceramic goods such as plates, bowls, vases or bottles are ideal for radial or tangential patterns due to their round basic shape. Geometric patterns often structure the naturalistic ornaments used.

Alhambra , detail of the Gireh wall decoration

Ỉznik ceramic bowl, 16th century, with pattern from group 6

Historical and art history sources

Written records of the construction and use of geometric elements from their time of origin are only sparsely preserved. The Topkapı scroll , made during the Timurid reign in Persia at the end of the 15th or beginning of the 16th century, contains 114 patterns for quarter or half-domes made from girih tiles , muqarnas , geometric ornaments and geometrically constructed calligraphy .

The 19th century Mirza Akbar scroll , now in the Victoria and Albert Museum , London, was put together by the court architect of the Qajar dynasty. In this manuscript, pinholes along the lines show that the manuscript served as a template for ornaments that were copied from the scroll. A third manuscript from the 16th century, similar in structure to the Topkapı scroll, comes from Bukhara , Uzbekistan.

Owen Jones published his influential work “ The Grammar of Ornament ” in 1856 , in which he established “general principles for the arrangement of form and color in architecture and the decorative arts” , represented by 100 colored plates in chromolithography with ornaments from all styles and ages Cultures were illustrated, including color tables of geometric Islamic ornaments.

Émile Prisse d'Avesnes published his three-volume work “ L'art arabe d'après les monuments du Kaire, depuis le VIIe jusqu'à la fin du XVIIe ,” in Paris from 1869–1877 , with 200 plates and a volume of text with numerous vignettes, in whom he described the "Arab" art, which he on a documentation trip to Egypt from 1858 to 1860 on behalf of Napoleon III. had met.

The work of Jules Bourgoin Les Arts arabes, architecture, menuiserie, bronzes, plafonds, revêtements, marbres, vitraux, etc. avec un texte descriptif et explicatif et le trait général de l'art arabe , Paris, 1867–1873, is in one English edition under the title “ Arabic Geometrical Pattern and Design ” still in print today.

Ernest Hanbury Hankin, who lived in British India for a long time , published a study on Mughal architecture in 1925 under the title " The Drawing of Geometric Patterns in Saracenic Art ". He defined a “geometric arabesque” as a pattern, formed “with the aid of construction lines, consisting of touching polygons”, and uses the example of the Akbar mausoleum (1605–1613).

Islamic patterns in modern mathematics

Peter Lu of Harvard University came in Darb-e Imam in Isfahan , Iran from the 15th century on patterns that the Penrose tiling seem to anticipate. Tile ornamentation in the sense of non-repeating, infinite tiling was demonstrated at the Gonbad-e-Kabud complex in Maragha , whereby a set of five easy-to-construct basic shapes, made up of Girih tiles in an equilateral polygonal shape, was used. From the 15th century, according to today's mathematical understanding, the property of self-similarity , as we know it from fractals , can be discovered. The girih in the Alhambra are considered to be an excellent example of the use of double periodic patterns in Islamic art. Whether or not all 17 known mathematical ornament groups appear in the Alhambra is controversial.

Web links

- Museum with no Frontiers: Geometric Decoration , accessed December 10, 2015.

- Animation of the Gireh pattern on the Topkapı scroll , accessed December 11, 2015

- Peter J. Lu and Paul J. Steinhardt: Decagonal and Quasicrystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture , Science (2007) , accessed December 11, 2015

- Utrecht University, Faculty of Science, Department of Mathematics - Seminar Mathematics in Islamic Arts 2010 , accessed on December 11, 2015

- Examples of Kufic script from the Topkapı scroll , accessed December 11, 2015

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Peter J. Lu and Paul J. Steinhardt: Decagonal and Quasi-crystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture . In: Science . 315, 2007, pp. 1106-1110. doi : 10.1126 / science.1135491 . Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- ↑ a b Branko Grünbaum: What Symmetry Groups Are Present in the Alhambra? In: Notices of the American Mathematical Society. Vol. 53, No. 6, 2006, ISSN 0002-9920 , pp. 670-673, digital version (PDF; 2 MB) .

- ↑ MD Ekthiar, PP Soucek, SR Canby, NN Haidar: Masterpieces from the Department of Islamic Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art . 2nd Edition. Yale University Press, New York 2012, ISBN 978-1-58839-434-7 , pp. 20-24 .

- ^ Dorothy K. Washburn, Donald W. Crowe: Symmetries of culture: Theory and practice of plane pattern analysis . University of Washington Press, Seattle 1988, ISBN 978-0-295-97084-4 .

- ↑ a b Peter Davies: Ancient Kilims of Anatolia . WW Norton, New York 2000, ISBN 0-393-73047-6 , pp. 40-44 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Eric Broug: Islamic geometric design . 1st edition. Thames & Hudson Ltd., London 2013, ISBN 978-0-500-51695-9 .

- ↑ Eric Broug: Islamic geometric design . 1st edition. Thames & Hudson Ltd., London 2013, ISBN 978-0-500-51695-9 , pp. 7 .

- ↑ Eric Broug: Islamic geometric design . 1st edition. Thames & Hudson Ltd., London 2013, ISBN 978-0-500-51695-9 , pp. 167-193 .

- ↑ Louis Werner: Zillij in Fez. Saudi Aramco World. May-June 2001, Vol. 52 (3), pp. 18-31. online ( Memento of the original from December 28, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed December 12, 2015

- ↑ Gülru Necipoğlu, in: Timurid Art and Culture - Iran and Central Asia in the fifteenth century (Ed .: L. Golombek and M. Subtelny): Geometric design in Timurid / Turkmen architectural practice: Thoughts on a recently discovered scroll and its late gothic parallels . EJ Brill, 1992. , online [1] , accessed December 10, 2015

- ^ Owen Jones: The Grammar of Orient . online , accessed December 12, 2015.

- ↑ Jules Bourgoin: Arabic Geometrical Pattern and Design . Dover Publications, 1974, ISBN 978-0-486-22924-9 .

- ^ Ernest Banbury Hankin: The Drawing of Geometric Patterns in Saracenic Art. Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India No. 15 . Government of India Central Publication Branch, 1925. online , accessed December 12, 2015

- ^ Philip Ball: Islamic tiles reveal sophisticated maths. Nature, February 22, 2007, [2] , accessed December 10, 2015