Knot theory

The knot theory is a research field of topology . Among other things, it deals with investigating the topological properties of nodes . One question is, for example, whether two given knots are equivalent, that is, whether they can be merged without the cord being “cut”. In contrast to knot theory, knot theory is not concerned with tying knots in practice, but with mathematical properties of knots.

Mathematical definition

Take a knotted piece of string and glue the two ends together; In technical terms, the result is an embedding of the circular line in the three-dimensional space. Two nodes are considered to be the same if they can be transformed into one another by a constant deformation ( isotopy ).

In knot theory, the embedding of several circular lines is also examined; these are called entanglements (links). Another extension of the topic are multi-dimensional nodes, that is, embedding of the spheres of the dimension in the -dimensional space for .

A three-dimensional, closed, smooth curve that is not knotted and is therefore isotopic to the circular line is called an unknot or trivial knot.

Technical details: tame knots and ambient isotopy

Strictly speaking, the above definition needs to be improved in two places in order to correspond to the conventional concept of knots, because:

- It allows wild knots, i.e. H. infinite number of knots in a (finite) piece of string.

- With an ordinary isotopy, you can pull a knot so tight that it disappears.

There are two ways to fix these problems:

- Isotopy is replaced by ambient isotopy and limited to tame knots: With an ambient isotopy, the space around the knot must also deform continuously; a knot is called tame if it is ambient isotopic to a piecewise linear knot.

- One restricts oneself to smooth isotopies between smooth nodes, because every continuously differentiable node is tame, and every smooth isotope can be extended to an ambient isotope.

Both solutions are equivalent. Furthermore, all nodes are considered tame.

Knot diagrams and Reidemeister movements

In knot theory, a knot is often represented by its projection onto a plane. Every (tame) node has a regular projection, i.e. H. a projection with only a finite number of colons (intersections).

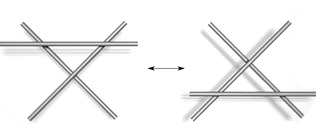

In order to be able to reconstruct the knot from a projection, one has to indicate at each intersection which of the two strands is above or below. A projection with this additional information is called a node diagram . Each tame knot can thus be represented by a diagram. However, such a diagram is not unique because each node can be represented by an infinite number of different diagrams. For example, the following local trains change the diagram but not the node shown:

; ; |

; ; |

. .

|

| Type I. | Type II | Type III |

These moves are called Reidemeister movements , in honor of Kurt Reidemeister . He showed in 1927 that these three moves are already sufficient: two node diagrams represent the same node exactly when they can be converted into one another by a finite sequence of Reidemeister movements.

Node invariants

Two nodes can look very different and still be the same in the above sense. As a result, it can be difficult to directly prove that two nodes are not the same. Therefore one chooses an indirect way: node invariants .

A node invariant assigns a number (or a polynomial or a group, etc.) to each node in such a way that the value does not change if the node is continuously deformed in three-dimensional space. In other words: you assign a value to each node diagram in such a way that the Reidemeister trains do not change the value. Examples:

- The number of crossings of a node is the smallest possible number of crossings that can be found in any node diagram of . The fact that the crossing number is an invariant can already be seen from its definition; but the calculation is generally very difficult.

- Alexander polynomial , the first polynomial variant of nodes, introduced by James Alexander in 1923

- HOMFLY polynomial

- The three-color number : A knot diagram consists of arcs and intersections; three arches meet at each intersection. In the case of a three-color scheme , each sheet is assigned one of the colors red, blue or green, in such a way that at each intersection the three sheets have either three different colors or three times the same color. The three color number is the number of three colorations. The three-colored number shows that the trefoil knot is knotted and that the Borromean rings are actually linked.

- The Jones polynomial assigns a Laurent polynomial to each node . The Jones polynomial can be calculated algorithmically with the help of node diagrams by adding suitable terms for all intersections to form an overall polynomial. For invariance it suffices to show that the polynomial constructed in this way is invariant among the three Reidemeister movements. The Jones polynomial can distinguish the trefoil knot from its mirror image. According to Edward Witten , it can be represented using observables ( Wilson loops ) of a three-dimensional topological quantum field theory , the Chern-Simons theory . This quantum field theory is also a gauge field theory, and depending on the choice of gauge group, different knot invariants are obtained (Alexander polynomial, HOMEFLY polynomial, Jones polynomial, etc.).

- By categorizing the Jones polynomial, Mikhail Khovanov introduced the Khovanov homology of links as a new knot invariant in the late 1990s . The Jones polynomial, HOMEFLY polynomial and Alexander polynomial are Euler characteristics of special homologies within the Khovanov homology. Edward Witten gave an interpretation as a topological quantum field theory - this time a supersymmetric gauge field theory in four dimensions - with Khovanov homology as the observable. Catharina Stroppel gave a representation-theoretical interpretation of the Khovanov homology by categorizing quantum group invariants. The Khovanov homology also has links to the Floer homologies .

- The system of Vasiliev invariants , a series of infinitely many knot invariants, which were introduced by Viktor Anatoljewitsch Wassiljew (Vassiliev) around 1990 . While in the usual knot theory an embedding of the circular line in the is considered - without singular points - Vasiljew considered the discriminant, i.e. the complement to the space of the nodes in the space of all images from the circular line in the . So he looked at the extension to singular nodes, which gives an infinite series of levels (non-singular, one colon, two colons, etc.). The Vasilyev invariants contain most of the previously known polynomial invariants. It is an open problem whether they are complete, that is, uniquely characterize the nodes. Maxim Kontsevich gave a combinatorial interpretation of the Vasilyev invariants. They can also be calculated in terms of perturbation theory using Chern-Simons theories.

Up to now, no easily computable node invariant has been found that distinguishes all non-equivalent nodes, i.e. is identical for two nodes exactly if they are equivalent. Finding one is an important goal of current research. It is also unknown whether the Jones polynomial recognizes the trivial node, i.e. whether there is a non-trivial node whose Jones polynomial is equal to that of the trivial node.

Disc knot

A knot in is called a (smooth) disk knot if it is the edge of a smooth disk in the half-space (the set of all with ). The disk belonging to the node is called the associated disk. Alternatively, disc nodes can be described as cross-sections of 2-dimensional nodes in . If one does not ask of the disk that it is smooth, but only that it is locally flat (a less strong property), one obtains the so-called topological disk nodes. For example, one can show that every node with a trivial Alexander polynomial is a topological disk node.

Many problems in knot theory are to determine whether a given knot is a slice knot. For example, it has only recently become known that the Conway knot is not a smooth disc knot . However, it is a topological disk knot because its Alexander polynomial is trivial.

Applications

For a long time, dealing with knots was of purely theoretical interest. In the meantime, however, there are a number of important applications, for example in biochemistry or structural biology , which can be used to check whether complicated folds of proteins correspond to other proteins . The same applies to DNA . There are other current applications in polymer physics . Knot theory occupies an important position in modern theoretical physics , where it is about paths in Feynman diagrams .

Knot theory is also used in related areas of topology and geometry. Knots are very useful for examining 3-dimensional spaces, since any orientable, closed 3-dimensional manifold can be created by stretching surgery on a knot or a loop. In hyperbolic geometry , nodes play a role because the complements of most nodes in the 3-dimensional sphere carry a complete hyperbolic metric.

literature

- Colin C. Adams: The Knot Book. An elementary introduction to the mathematical theory of knots. 1994; 2004, ISBN 0-8218-3678-1

- The knot book. Introduction to the mathematical theory of knots. Spectrum, Heidelberg / Berlin / Oxford 1995, ISBN 3-86025-338-7

- Meike Akveld: Knots in Mathematics. A game with strings, pictures and formulas. Orell Fuessli, Zurich 2007, ISBN 978-3-280-04050-8

- Gerhard Burde, Heiner Zieschang : Knots. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1985, ISBN 3-11-008675-1

- Gunnar Hornig: Magnetic secret . In: RUBIN - The science magazine of the Ruhr University Bochum. 2/01, pp. 6–10, ruhr-uni-bochum.de (PDF)

-

Louis H. Kauffman : Knots and Physics. World Scientific, 1991, ISBN 981-02-0343-8

- Node. Diagrams, state models, polynomial variants. Spectrum, Heidelberg / Berlin / Oxford 1995, ISBN 3-86025-232-1

- Charles Livingston: Knot Theory for Beginners , Vieweg, 1995, ISBN 3-528-06660-1

- Lee Neuwirth: Knot Theory. In: Spectrum of Science . August 1979, ISSN 0170-2971 (among others: model of a mathematical knot, relationships between geometry and algebra)

- Dale Rolfsen: Knots and Links. AMS Chelsea Publ., 2003, ISBN 0-8218-3436-3

-

Alexei Sossinsky : Nœuds. Genèse d'une théorie mathématique. Éditions du Seuil, Paris 1999, ISBN 2-02-032089-4 ( Science Ouverte ).

- Mathematics of knots. Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Reinbek 2000, ISBN 3-499-60930-4

Web links

- Robert G. Scharein: The KnotPlot Site . (Software for interactive visualization, manipulation and simulation of mathematical nodes)

- Cha, Liviongston: Table of knot invariants

- Alexander Stoimenow: Knot data tables

- Marc Lackenby: Elementary Knot Theory (misleading title, it is an introduction to current research)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gerhard Burde, Heiner Zieschang : Knots . 2nd Edition. de Gruyter, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-11-017005-1 , p. 2 .

- ↑ Gerhard Burde, Heiner Zieschang : Knots . 2nd Edition. de Gruyter, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-11-017005-1 , p. 2-3 .

- ↑ Richard H. Crowell, Ralph H. Fox : Introduction to Knot Theory . Springer, New York, ISBN 0-387-90272-4 , pp. 5 (statement 2.1).

- ↑ Florian Deloup: The fundamental group of the circle is trivial . In: The American Mathematical Monthly . tape 112 , no. 5 , May 2005, pp. 417-425 , doi : 10.2307 / 30037492 (Theorem 5).

- ↑ Victor V. Prasolov, Alexei B. Sossinsky : Knots, Links, Braids and 3-Manifolds (= Translations of Mathematical Monographs . Volume 154 ). American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI 1997, ISBN 0-8218-0588-6 , pp. 8 (§1.3).

- ↑ Richard H. Crowell, Ralph H. Fox : Introduction to Knot Theory . Springer, New York, ISBN 0-387-90272-4 , pp. 7 (statement 3.1).

- ↑ Knot Invariant , ncatlab

- ↑ Charles Livingston: Knot Theory for Beginners . Vieweg, Braunschweig / Wiesbaden 1995, ISBN 3-528-06660-1 , pp. 116 .

- ↑ Charles Livingston: Knot Theory for Beginners . Vieweg, Braunschweig / Wiesbaden 1995, ISBN 3-528-06660-1 (sections 3.2 and 3.3).

- ↑ Khovanov Homology , ncatlab

- ^ Vassiliev Invariant , Mathworld

- ^ Charles Livingston: Knot Theory for Beginners, Vieweg, 1995