Anatolian carpet

An Anatolian carpet (also: Turkish carpet ) is a heavy textile floor covering that is traditionally produced by hand in the geographical region of Anatolia or Asia Minor and the neighboring areas for personal use, local trade and export. Anatolian carpets form an important part of the culture and heritage of Turkey today .

Carpet knotting is a traditional handicraft that goes back a long way to pre-Islamic times. In the course of the long history of Anatolia and the handicrafts of carpet manufacture, various cultural influences have been integrated into the design. Traces of Byzantine ornaments have been preserved in the carpet patterns as well as the traditional patterns and decorations of the Turkic peoples who immigrated from Central Asia. Even Greeks , Armenians , Caucasian and Kurdish tribes living in Anatolia or immigrated at different times there have introduced their traditional pattern. The adoption of Islam and the development of Islamic artinfluenced the design profoundly. The political and ethnic history and diversity of Asia Minor can thus be read from the patterns of carpet weaving.

Around the 12th century AD, when political and trade relations between Western Europe and the Islamic world became more intense, Anatolian knotted carpets also became known in Europe. Because direct trade was first established between the Ottoman Empire and Europe , oriental carpets were initially only known under the trade name “Turkish” carpets in Europe, regardless of their actual country of origin. It was only after the scientific interest of Western European art historians was awakened in the late 19th century that the artistic and cultural diversity of the Anatolian carpet was better understood.

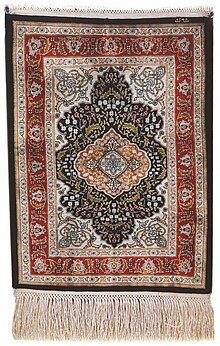

Within the group of oriental carpets , the Anatolian carpet is characterized by characteristic colors, patterns, structures and techniques. Mostly made of wool and cotton, sometimes also consisting of silk, Anatolian carpets are usually knotted with the symmetrical (“Turkish” or “Gördes” knot ). The formats range from small pillows ( yastik ) to large carpets that fill the room. The earliest surviving Turkish carpets date from the 13th century. Since then, different types of carpets have been continuously produced in factories , more provincial workshops, in villages, small settlements or by nomads . Each social group knows characteristic techniques and uses characteristic materials. Scientific attempts to assign a certain pattern to an ethnic, regional, or even just the nomadic or village tradition have so far been unsuccessful due to the continuous exchange of patterns in the context of extensive migrations and the influence of commercial production.

Traditional Turkish carpets were valued as works of art not only in their country of origin but also in Western Europe. Oriental carpets are already depicted on European paintings from the Renaissance period. Since the 19th century they have also been scientifically researched by art historians in Western Europe and Turkey. For some time now, flat woven fabrics ( Kelim , Sumak, Cicim, Zili) have also attracted the interest of collectors and scientists.

Initiatives such as the DOBAG initiative emerged in the 1980s, followed by the Turkish Cultural Foundation in the 2000s , the aim of which is to revive the traditional art of carpet-knitting with hand-spun wool dyed in natural colors and in traditional patterns.

history

It is likely that carpets with a knotted pile were first made by wandering nomads in geographical regions whose climate made it necessary to protect themselves from the cold ground in the tents. All items, including the looms needed to make them, had to be easy to transport. The raw materials also had to be readily available on the hike. Sheep and goats provided wool, and natural colors could be obtained from plants and minerals from the region. The knotted textiles could, depending on their design and size, represent both everyday objects and jewelry.

The origin of carpet knotting remains in the dark, because textiles wear out with use, are attacked by pests or rot easily. The controversy surrounding the alleged evidence of flat woven fabrics in the 7th millennium BC The settlement of Çatalhöyük , dated to the 3rd century BC, was ended when the excavation report was exposed as a forgery.

The oldest surviving knotted carpet is the Pasyryk carpet , which dates back to the 5th century BC. Is dated. Its place of manufacture is unknown, but its fine knotting in symmetrical knots and the finely worked pattern show that the craft of carpet knotting had already reached a high technical and artistic maturity at this early time.

The history of the Anatolian carpet must be seen in the context of the political and ethnic history of Anatolia. Anatolia is one of the countries where the oldest civilizations in the world lived, the Hittites , Phrygians , Assyrians , Persians , Armenians , Greeks . The city of Byzantion was founded in the 7th century BC. Founded by Greek settlers, destroyed and rebuilt as a Roman city in 303 AD by the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great . Carpet knotting was probably already known in Anatolia at that time, but no carpets have survived that could prove this. In 1071 AD the Seljuk Alp Arslan defeated the Eastern Roman Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes in the battle of Manzikert . This victory is seen as the beginning of the rise of the Seljuks while Anatolia was lost to the Byzantine Empire.

Seljuk carpets: travelogues and the fragments from Konya

In the early 14th century, Marco Polo wrote in his travelogue:

"... et ibi fiunt soriani et tapeti pulchriores de mundo et pulchrioris coloris."

"... and here they make the most beautiful silk fabrics and carpets in the world, and in the most beautiful colors."

Coming from Persia, Polo traveled from Sivas to Kayseri. Abu l-Fida quotes Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi, who reported on carpet exports from Anatolian cities in the late 13th century: "This is where Turkoman carpets are made, which are traded in all other countries". He, like the Moroccan merchant and traveler Ibn Battuta, name Aksaray as a major center of carpet weaving in the early to mid-14th century.

The oldest surviving knotted Anatolian carpets were found in Konya , Beyşehir and Fustāt and dated to the 13th century. They come from the time of the Sultanate of the Rum Seljuks . Eight fragments were found in 1905 by Frederic Robert Martin in the Alâeddin Mosque of Konya , four more were found by RM Riefstahl in 1925 in the Eşrefoğlu Mosque in Beyşehir in Konya Province. More fragments appeared in Fustāt, Egypt.

Due to their original size (Riefstahl published a carpet that is 6 m long), the Konya carpets can only have been made in a specialized city manufactory, because looms of this size do not find a place in a village house or a nomad tent. It is not known exactly where these carpets were once knotted. The field patterns of Konya carpets are mostly geometric and rather small in relation to the size of the carpet. The very similar patterns are arranged in diagonal rows: hexagons with straight or hooked outlines; Squares with stars in them and ornaments in between, similar to Kufic script; Hexagons or stylized flowers and leaves in diamond ornaments. The main border often contains Kufic ornaments. The corners are not "dissolved", which means that the pattern of the border appears cut off at the corners and does not continue around the corner. The colors (blue, red, green, more rarely white, brown, yellow) appear subdued. Often two different shades of the same color are right next to each other. No two patterns are alike on these carpets.

The carpets from Beyşehir are very similar to those from Konya in terms of pattern and color. In contrast to the animal carpets of the following period, images of animals are rarely seen on the Seljuk carpets. On some fragments there are horned quadrupeds facing each other, or birds on either side of a tree.

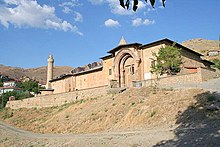

The style of the Seljuk carpets shows parallels to architectural decorative elements of contemporary buildings such as the Divriği Mosque or buildings in Sivas and Erzurum and could be related to ornaments of Byzantine art. Today the carpets are kept in the Mevlânâ Museum in Konya, and in the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art in Istanbul .

Carpet fragment from the Eşrefoğlu Mosque, Beyşehir , Anatolia. Seljuk period, 13th century

Carpet fragment from the Eşrefoğlu Mosque, Beyşehir , Anatolia. Seljuk period, 13th century

Animal carpet, Anatolia, 11. – 13. Century, Museum of Islamic Art (Doha)

Anatolian Beyliks

In the early 13th century, the Mongols invaded Anatolia. Taking advantage of the weakness of the Seljuk rule, Turkmen tribes, the Oghuz , united to form independent domains, the Beyliks . The sultans Bayezid I (1389–1402), Murad II (1421–1481), Mehmed II (1451–1481), and Selim I (1512–1520) gradually conquered the Anatolian Beyliks and subdivided them into the Ottoman Rich a.

Tales like the Dede Korkut confirm that the Turkmen tribes in Anatolia knotted carpets. It is not known what these carpets looked like because we cannot identify them. One of the Turkmen tribes, the Tekke, settled in southwestern Anatolia in the 11th century, but later moved back to their present area on the Caspian Sea. The Tekke tribes of Turkmenistan, who lived in the area around Merv and Amu Darya in the 19th century, knotted a special type of carpet, which is characterized by stylized floral motifs (" göl ") that appear repeatedly in rows on the field.

Ottoman Empire

Around the year 1300 a group of Turkmen tribes, now known as the "early Ottomans", migrated westward under Suleiman and Ertuğrul Gazi . Under Ertuğrul's son Osman I , they founded the Ottoman Empire in northwestern Anatolia . In 1326 the Ottomans captured Bursa , which became the first capital of the Ottoman Empire. In 1517 the Ottoman Empire defeated the Egyptian Sultanate of the Mamluks in Cairo in the Ottoman – Mamluk War (1516–1517).

Suleyman I , the tenth Sultan (1520–1566), invaded Persia and forced the Persian Safavid Shah Tahmasp I (1524–1576) to move his capital from Tabriz to the safer Qazvin , until 1555 the peace of Amasya could be closed.

With the growing political and economic influence of the Ottoman Empire, the capital Istanbul became a meeting place for diplomats. Dealers and artists. During the reign of Süleiman I, artisans and artists of various specializations worked together in the court manufactories (" Ehl-i Hiref "). Calligraphy and miniature painting in the scriptorias (“ nakkaşhane ”) exerted a strong influence on the design of the carpet patterns. In addition to Istanbul, different specialized court manufacturers were also located in Bursa , İznik , Kütahya and Uşak . Bursa was known for its silk fabrics and brocades, Iznik and Kütahya for ceramics and tiles, Uşak, Gördes and Ladik for carpets. The Uşak region produced some of the finest carpets of the 16th century. It is very likely that the “Holbein” and “Lotto” carpets were knotted here.

Animal carpets

|

|

|

|

Left picture : “Phoenix and Dragon” carpet, 164 × 91 cm, Anatolia, approx. 1500, Pergamon Museum , Berlin

Right image : Animal carpet, around 1500, Marby Church, Jämtland , Sweden . Wool, 160 × 112 cm, State Historical Museum , Stockholm |

||

Very few carpets from the transition period between the Seljuks and the early Ottoman empires have survived. A traditional Chinese motif, the fight between the phoenix (Chinese Fenghuang ) and the dragon can be found on an Anatolian carpet, today in the Pergamon Museum , Berlin. Radiocarbon analyzes date the carpet to the middle of the 15th century and thus to the early Ottoman Empire (Rageth, 2004, pp. 106–109). The carpet is tied with symmetrical knots (Beselin, 2011, pp. 46–47). The Chinese motif was likely introduced into Islamic art by the Mongol invaders during the 13th century .

Another carpet with two medallions showing birds facing each other on either side of a tree was found in the church in Marby, Jämtland Province , Sweden . The radiocarbon dating indicates an origin between 1300 and 1420. Fragments of this type of carpet were also found in Fustāt. The field of the “Marby” carpet is divided into two rectangles, each of which contains an octagon with two birds and a tree. The tree appears to be mirrored along the central horizontal axis of the medallion as if on a surface of water.

Until 1988, the “Phoenix and Dragon” and the “Marby” carpets were the only known “animal carpets” from Anatolia. Since then, seven more carpets of this type have appeared. They come from Tibetan monasteries, from which they were taken by monks who fled to Nepal before the Chinese Cultural Revolution . One of these carpets was acquired for the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art . It shows parallels to a painting by the Sienese artist Gregorio di Cecco: " The Wedding of the Virgin " from 1423. Large animals facing each other appear on the carpet, each with a small animal inside.

Animal carpets were depicted on European paintings of the Renaissance paintings in the 14th and 15th centuries and represent the earliest group of oriental carpets known in Europe for which comparative pieces have been preserved. They give an idea of what the carpets knotted in the late Seljuk and early Ottoman times might have looked like. Towards the end of the 15th century, this type of carpet disappeared and purely geometric ornaments became more common. This is associated with stricter compliance with the Islamic ban on images in the early Ottoman Empire.

"Holbein" and "Lotto" carpets

Anatolian carpets of the "Holbein" and "Lotto" types were named after Renaissance painters by European art historians of the 19th century, because the carpets of this type were initially only known from the paintings of these painters . Due to the distribution and size of the geometric medallions in the carpet field, a distinction is made between small and large-patterned "Holbein" carpets. The small-figured type is characterized by small octagons arranged in a regular row with a star pattern on the inside, which are entwined with arabesques . The big-figured type shows two or three large medallions, often enclosing eight-pointed stars. The MAK in Vienna, the Louvre in Paris, the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art in Istanbul keep particularly beautiful carpets of this type.

The oldest “Lotto” carpets have “pseudo-Kufic” main borders. The field usually has a red background and is covered with bright yellow leaf ornaments on the underlying repeat pattern of geometric arabesques alternating with cross-shaped, octagonal or diamond-shaped ornaments. Carpets of various sizes up to 6 m² have been preserved. CE Ellis distinguishes three main groups of the "Lotto" pattern: the "Anatolian", "Kelim" and the "ornamental" style.

“Holbein” and “Lotto” carpet patterns have little in common with the decorative patterns and ornaments seen on other objects of Ottoman art. Briggs showed similarities between these two types of carpets and those depicted on Timurid book illuminations. The pattern tradition of the “Holbein” and “Lotto” carpets could therefore go back to the Timurid period.

Type I (small pattern) "Holbein" carpet, Anatolia , 16th century.

Harem, Topkapi Palace , carpet in small-sized "Holbein" design

Type IV (large-patterned) "Holbein" carpet, 16th century, Anatolia .

Western Anatolian “Lotto” carpet, 16th century, Saint Louis Art Museum

Usak carpets

|

|

|

|

Left picture : “Medallion” Uşak carpet.

Right picture : White-ground “Selendi” carpet, Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art |

||

Star, medallion, double niche "Uşak carpets"

The region around the city of Uşak was mentioned by Evliya Çelebi as an important center of carpet production as early as 1671 . An Istanbul price register (“ narh defter ”) from 1640 already lists ten different types of Uşak carpets. A customs register from Caffa in the Crimea for the period from 1487 to 1491 also mentions carpets from Uşak and thus provides evidence of the long tradition of carpet production in this region. Records show that Uşak carpets were made on behalf of the Sultan to furnish mosques, especially for the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne . Compared to the large number of Uşak carpets known from Western Europe, especially Italy, only relatively few carpets of this type have survived in Turkey itself.

Stern-Uşak carpets were produced in various, often very large, formats. They are characterized by large star-shaped main medallions in an infinite repeat on a red field with secondary floral ornaments. The pattern is very likely influenced by northwest Persian book art or Persian medallion carpets. Compared to the medallion usak carpets, the concept of the “infinite repeat” appears to be pursued more consistently and more in line with the early Anatolian design tradition. The consistent reference to the infinite repeat allows the production of a wide variety of formats, since only a more or less large section of the repeat pattern has to be used.

Medallion usak carpets usually have a red or blue field decorated with flower grids or leaf tendrils, egg-shaped medallions alternating with smaller eight-lobed stars, or lobed medallions with interwoven floral decorations. Their border often shows palmettes on floral or leaf tendrils and “pseudo-Kufic” characters.

With their curvilinear pattern, the Medaillon Uşak carpets differ significantly from the patterns of older Anatolian carpets. Their appearance in the 16th century indicates a possible influence by Persian pattern formation. After the Ottomans occupied the former Persian capital Tabriz in the first half of the 16th century , they must have known Persian medallion carpets. Some pieces were in Turkish possession early on. Kurt Erdmann found some Persian specimens from this period in the Topkapı Palace . The medallion of the Uşak carpet, understood as part of an infinite repeat, represents a specifically “Turkish” idea that clearly stands out from the Persian understanding of the pattern of the independent central medallion.

Star and medallion usak carpets represent an important innovation because it was on them that floral motifs appeared on Turkish carpets for the first time. The replacement of the geometric by floral ornaments and the use of large, centered pattern compositions instead of the conventional infinite repeat was described by Kurt Erdmann as a "pattern revolution".

Another small group of usak carpets is called double niche usak . When they were designed, the corner medallions were moved so closely together that they form a niche at both ends of the carpet. This is understood as a special form of the (directed) prayer rug pattern, because an ornament that looks like a mosque lamp often hangs down from the top of one of the niches into the field. Viewed differently, this pattern scheme results in a classic Persian medallion pattern. In contrast to the Persian tradition, some double niche usaks have an additional central medallion. The double niche carpets are seen as an example of the integration and remodeling of Persian patterns into an older Anatolian pattern tradition.

White-ground "Selendi" carpets

On other carpets from the Uşak area, the floral pattern elements have been replaced by other motifs such as the so-called Cintamani motif, which consists of three colored spheres arranged in a triangle and spread over the field in an endless repeat. Often two wavy lines are drawn under the base of each triangle. This motif usually appears on a white background. Together with the bird and the small group of the scorpion carpets, they are grouped together as white-ground carpets. Bird carpets have a continuous pattern of quatrefoils that each enclose a rosette. Despite their geometric design, the patterns look like a row of birds. An official Ottoman price list (narh defter) from 1640 contains a “white carpet with a leopard print” from the town of Selendi, near Usak. This is why the white-ground carpets have been called Selendi carpets since this source discovery .

Cairene Ottoman carpets

After the conquest of the Mamluk Sultanate in Egypt by the Ottoman Empire in the Battle of Marj Dabiq near Aleppo and the Battle of Raydaniyya outside Cairo , two different cultures merged, which is also very clearly evident in local carpet production after this period. The earlier traditional weaving of the Mamluk workshops used clockwise ("S" -) spun wool that was twisted counter-clockwise ("Z" -) and a very limited range of colors and hues. After the conquest, Ottoman patterns found their way into the carpets, which were still knotted with wool that was spun and twisted using the old technique. The so-called Cairene Ottoman carpets were made in both Egypt and probably in Anatolia until the early 17th century.

Cairen Ottoman carpet, 16th century Museum of Applied Arts Frankfurt St. 136

“Chessboard” or compartment carpets from the 17th century

An extremely rare group of carpets that were previously thought to be derived from the Mamluk and Kairen Ottoman carpets are the chessboard or compartment carpets. Their origin is still controversial. The choice of color and pattern of the carpets are similar to those of the Mamluk carpets, but they are "Z-spun" and "S-twisted", similar to the early Anatolian and Caucasian carpets. Since the early 20th century, Damascus has been assumed to be the production site for lack of more precise information. Pinner and Franses argue in this direction, since Syria used to be part of the Mamluken and later the Ottoman Empire. which could explain the similarity of patterns and colors with the Cairene carpets. The dating of the checkerboard carpets also corresponds to the registration of “Damascus” carpets in European collectors' inventories from the early 17th century. Checkerboard carpets are also shown in Pietro Paolini's (1603–1681) self-portrait and in Gabriel Metsu's painting “Die Musikfreunde”.

Only about thirty of these carpets are known, all of which have a similar pattern shape composed of squares, in each of the corners of which there are triangles that enclose a star pattern. The pattern made up of these squares gave the carpets their name. The carpet group includes both large and small formats, with the large formats having more diverse patterns. The small formats are only known in two pattern variants: in one variant the triangles form an octagonal inner field for the star pattern, in the second variant, which could perhaps be a simplification of the first, the triangles that form the inner field for the star pattern are something extended and interconnected. All small-format chessboard carpets have a main border with cartouches and lobed medallions.

"Transylvanian" carpets from the 16th to 18th centuries Century

|

|

|

|

Left picture : Pieter de Hooch " Portrait of a family making music ", 1663

Right picture : Carpet of the Transylvanian type, 17th century. |

||

Transylvania , in today's Romania , belonged to the Ottoman Empire from 1526 to 1699. The region was an important center for trade with Europe. In Transylvania, too, Turkish carpets were very much appreciated and were often used as jewelry in wealthy homes, but especially to decorate Christian churches. You can still find antique oriental carpets from the period between the 16th and 18th centuries in the Protestant churches of the Transylvanian Saxons . The most important collection of these so-called “ Transylvanian carpets ” is still in the “Black Church” in Brașov . In the fortified churches , which were often built for defense , the carpets survived the eventful history of the country and were also protected from wear and tear because they were mostly only used for decoration or were stored in the church. The carpets are therefore often still in excellent condition despite their age. Among them are rare Anatolian carpets of the "Holbein", "Lotto" and "white-ground" Selendi types.

The term “Transylvanian carpets” comes from the early 20th century, when it was not yet clear that the carpets were actually made in Anatolia. In a narrower sense, it is nowadays understood to be rather small-format carpets with main borders, which are decorated with rows of elongated, angular cartouches, the interior of which is filled with stylized floral patterns, sometimes alternating with shorter star rosettes or cartouches. The field often has a prayer niche pattern filled with two pairs of vases with flowered tendrils symmetrically arranged along the central horizontal axis. In other pieces the field ornament is condensed into medallions of concentric, rounded diamonds and rows of flowers. The spandrels of the single or double niches contain rigid arabesques or geometric, rectilinear rosettes and leaf ornaments. The basic color is yellow, red, or dark blue. Church registers, trade registers and preserved archives on the one hand, and the depiction of such carpets in Dutch paintings of the 17th century on the other hand, allow the carpets to be dated very precisely.

At the time when the Transylvanian carpets were first depicted in Dutch paintings, royal and noble people had already begun to be portrayed with carpets of Persian and Indian origin, which were already considered to be precious and rare. The not quite so affluent citizens could still be depicted with the Anatolian carpets. The "Portrait of Abraham Graphaeus" by Cornelis de Vos from 1620, and Thomas de Keyser's "Portrait of an Unknown Man" (1626) as well as the "Portrait of Constantijn Huyghens and his secretary" (1627) are among the earliest paintings on which Ottoman Manufactory carpets of the "Transylvanian" type can be seen. Transylvanian commercial registers, customs clearances and other archival sources show that these carpets were exported to Europe in large quantities. This likely suggests that the demand for Anatolian carpets had risen sharply after a growing upper class at the time was able to afford these luxuries.

Anatolian carpets of the “Transylvanian” type used to be found in the churches of other European countries such as Hungary, Poland, Italy and Germany. They were mostly sold later and ended up in European and American museums and private collections. Besides the Transylvanian churches today also preserve Brukenthal Museum in Sibiu ( German Hermannstadt ), the Museum of Fine Arts , the Budapest, Metropolitan Museum of Art , and Skokloster Castle in Sweden important collections "Transylvanian" carpets.

In Anatolia itself only a few carpets, mostly small in size, from the transition period between the “classical” Ottoman period and the 19th century have survived. The reason for this is unknown. At the same time, Western European residences from this period are also less often decorated with oriental carpets. Probably only small quantities of carpets were exported at the time, perhaps because fashion had changed.

19th century: “Mecidi” style and the Hereke court manufactory

Towards the end of the 18th century, the “ Turkish Baroque ” or “Mecidi” style developed based on the French Baroque . Carpets were made according to patterns from the French Savonnerie and Aubusson factories. Sultan Abdülmecid I (1839–1861) built the Dolmabahçe Palace on the model of Palace of Versailles .

In 1843 a weaving mill was founded in Hereke , a coastal town 60 km from Istanbul in the Bay of İzmit . Hereke supplied the royal palaces with silk brocades and other fabrics. The Hereke court factory originally also owned looms for cotton fabrics. Silk brocades and velvets were made in a workshop known as a " kamhane ". In 1850 the cotton weaving mill was relocated to Bakirköy, west of Istanbul, and jacquard looms were set up in Hereke. While the manufactory produced exclusively for the Ottoman court in the first few years, its products were also generally available in the grand bazaar , Kapalı Çarşı, from the second half of the 19th century . In 1878 the manufactory was badly destroyed by fire and only reopened in 1882. Carpet manufacture in Hereke began in 1891. For this purpose, experienced carpet weavers from the knotting centers Sivas , Manisa and Ladik were appointed. The carpets were exclusively hand-knotted and initially only intended for the court and as diplomatic gifts. Only later was it also produced for export.

Hereke carpets are best known for their very fine weave. Silk and occasionally fine wool yarn, more rarely gold, silver or cotton yarn were used for this. The earliest Hereke carpets, which are still exhibited today in the Topkapı and other palace museums, feature a variety of colors and patterns. The typical “palace carpet” has intricate floral patterns. The medallion patterns of earlier Uşak carpets were used very often. Prayer carpet patterns from Hereke show geometric ornaments, tendrils and mosque lamps in the field, and the typical mihrab prayer niche. The term “Hereke carpet” has become the trade name for finely knotted carpets of the highest quality, regardless of where they are made.

Modernity: decline and revival

|

|

|

|

Left picture : Southwest Anatolian carpet with bright but harmonious colors.

Right picture : Kurdish tent bag ( chowal ), approx. 1880, with harsh synthetic colors |

||

The modern history of the Anatolian carpet begins in the late 19th century when the demand for oriental carpets increased sharply in the international market. The traditional hand-knotted carpet, dyed with natural colors, is a very labor-intensive product, as every step of its production, from extraction, cleaning, spinning, dyeing of the wool, opening the loom and tying each individual knot by hand, is very time-consuming . With the intention of reducing the effort and increasing profit in the face of increasing competition, the factories introduced synthetic colors, machine looms and standardized patterns. This led to a rapid decline in centuries-old traditions. Art historians recognized and complained about the degeneration of the old handicrafts early on. Above all, the introduction of synthetic colors, which were initially not lightfast and moisture-resistant, seems to have accelerated the process of decay of the tradition.

In the late 20th century, the loss of cultural heritage was recognized, and initiatives arose to counteract this and to revive traditions. From the 1980s onwards, the DOBAG initiative in Western Anatolia, and from the early 2000s onwards also the Turkish Cultural Foundation , endeavored to revive the old knotting traditions with hand-spun wool dyed with natural colors. The return to traditional dyeing and knotting and the renewed interest of buyers in such carpets was described by Eilland as the “carpet renaissance”.

Materials, technology, processes

In traditionally oriented households, women and girls mostly produce carpets and flat woven fabrics, both to pass the time and to earn money. Girls learn the craft and, if necessary, the traditional carpet patterns at a young age. As in most cultures, it is predominantly women who weave and knot at home. Men only work in modern factories.

Traditionally hand-knotting a rug is a time-consuming process that can take weeks to months, depending on the size and quality.

material

Natural fibers are predominantly used for hand-knotted carpets. The most common materials are wool, silk, and cotton. Nomads in particular also use goat hair and (rarely in Anatolia) camel wool.

Wool is the material that is most often used for knotting carpets because wool is soft, durable, easy to work with and (if it is produced in-house) not too expensive. Wool does not accept dirt as easily as cotton, does not become electrostatically charged and insulates against heat and cold. These properties are not as pronounced in other natural fibers. The natural colors of wool are white, brown, yellowish brown, yellow and gray. They can be knotted into carpets undyed. Sheep wool absorbs dyes well. Wool is traditionally spun and twisted by hand and dyed with natural dyes, but it can also be machined into yarn and dyed with synthetic dyes.

Cotton is mainly used for the basis of the carpet, the warp and weft threads into which the pile is knotted. Cotton is more tensile than wool and does not warp as easily, which is why carpets with a cotton base are more regular and lie flatter on the floor than those with a wool warp and weft. In Munich areas, cotton is also used in the pile, mostly to achieve white color accents. Cotton refinedthrough mercerization has a silky sheen. Mercerized cotton yarn, like silk, can also be used in the pile to produce fine, silk-like carpets more cheaply and to offer them at a lower price.

Wool on wool (wool pile on wool weft and warp): The traditional Anatolian knotting outside of the court and town manufactories often uses this structure. Wool cannot be spun as finely as cotton, which is why the knot is not quite as dense and the number of knots is not quite as high as when warp and weft threads made of cotton are used. Wool threads cannot be stretched as tightly, so carpets on a wool base are more likely to warp and sometimes do not lie completely flat on the floor.

Wool on cotton (wool pile on cotton weft and warp): Cotton is stronger than wool yarn and can be spun and twisted more densely. This combination of materials allows the creation of finer patterns. Since the cotton base does not warp as easily as a woolen structure, these carpets are more regular in shape and lie flatter on the floor. A “wool on cotton” carpet often indicates an urban or larger workshop. Since the pile can be knotted more densely, these carpets are usually heavier than pure wool fabrics.

Silk on silk (silk pile on silk weft and warp): The fine, stable silk threads in this construction allow extremely fine knots with a knot density of up to 28 × 28 knots / cm². Since silk yarns are not as elastic as wool yarns, pure silk carpets are more delicate and are used as wall decorations rather than on the floor.

Spinning the yarn

The fibers of wool, cotton or silk are spun either by hand using a hand spindle or mechanically using a spinning wheel or industrial spinning machines by drawing and twisting the fibers into a yarn. Several individual yarns are usually twisted or twisted together again because of their greater thickness and stability. The direction in which the yarn is spun and twisted is referred to as either “Z-” (clockwise) or “S-spinning / twisting” (counterclockwise). Usually hand-spun single yarns are spun with a Z-twist and then twisted with an S-twist. This also applies to almost all oriental carpets, including the Persian carpet, with the exception of the S-spun and Z-twisted yarns of the Mamluk and the Cairene Ottoman carpets developed from this type of carpet.

Dyes and coloring

Traditional natural colors are obtained from plants and insects. The English chemist William Henry Perkin invented mauvein , the first synthetic paint , in 1856 . A large number of synthetic dyes came onto the market in the period that followed. Cheap, easy to attach and use, they have been used in Ușak carpets since the mid-1860s. The first synthetic dyes were found to be extremely unstable to light and moisture. They were so disappointing that the Persian rulers even tried to restrict their spread by law and with tax measures. (Gans-Ruedin 1978, p. 13).

In Turkey there are no known attempts to restrict the use of synthetic colors, so that within a few years the old craft tradition of natural coloring in Anatolia was almost completely abandoned and finally forgotten. In the eighties of the 20th century, the old natural colors were redetermined by chromatographic dye analyzes from wool samples from antique carpets and the dyeing process was experimentally reconstructed.

After these analyzes, the following natural colors were used in Anatolian carpets:

- Red from the roots of the madder (Rubia tinctorum),

- Yellow from locally different plants, including onion skins (Allium cepa), various chamomile species ( dog chamomile [Anthemis], real chamomile [Matricaria chamomilla]), and milkweed (Euphorbia),

- Black : gall apple , acorns , gerber sumac (Rhus coriaria),

- Green by double coloring with indigo and yellow dye,

- Orange by double coloring with madder red and yellow dye,

- Blue : from indigo , obtained from the indigo plant (Indigofera tinctoria).

The dyeing process begins with the preparation of the wool in order to make it receptive to the dyes. To do this, the washed wool is dipped in a pickling solution. It then remains in the dye solution for a certain time and is then dried in the air and in the sun. Indigo-dyed wool comes out of the solution with a yellowish dyed color; the blue only develops through oxidation in the air. Some colors, especially dark brown and light green, need ferrous stains for the coloring to succeed. These stains attack the wool fibers, so that the pile in the areas of a carpet treated with these colors wears out faster and more. This can create a relief effect in older Anatolian carpets, the presence of which suggests traditional coloring.

In contrast to this, almost any color and color intensity can be achieved with modern synthetic paints. With a carefully made modern carpet, it is almost impossible to tell with the naked eye whether natural or artificial colors have been used.

Knotting and post-processing

Carpets are made on a loom , a horizontal or upright frame. Warp threads are stretched on this , into which rows of knots are alternately tied and weft threads are woven in. The warp threads can be colored, usually red or blue.

The weaving of the carpet begins from the lower end of the loom by introducing a number of horizontal weft threads across the vertically stretched warp threads. The warp and weft threads form the basis of the carpet. The edges on the narrow sides often consist of more or less wide strips of flat woven fabric without pile. Knots made of wool, cotton or silk yarn are then tied individually by hand around the warp threads. Most carpets from Anatolia use the symmetrical (“Turkish” or “Gördes”) knot. Each knot is looped around two warp threads in such a way that both ends of the pile thread between two warp threads are pulled forward again. The thread is then pulled down and cut with a knife.

When a series of knots is completed, one or more weft threads are woven in again to hold the knots in place. The weft threads are then tapped down onto the row of knots with a heavy, comb-like instrument, thus compacting the fabric. When the pile is finished, a flatweave edge is often added again before the carpet is removed from the loom. The protruding ends of the warp threads are attached and form the fringes. The long sides of the carpet are also attached and form the edges. The pile is then sheared to a uniform length (previously with a special blade, today with a machine that moves over the pile in a similar way to a grinding machine), and the carpet is then washed. Washing with chemical solutions, such as diluted chlorine bleach, can change the color of the carpet. A carpet can be artificially aged by either machining it or, as in the past, placing it on the street or in the sun for a while.

The upright pile of the rug usually slopes towards the bottom of the rug because each knot is pulled down and tightened before the thread is cut. If you run your hand over a carpet, the feeling is similar to that when you run your hand over an animal's skin: Every hand-knotted carpet has a “line”. From the direction of the carpet line you can determine which is the lower edge of the carpet, or at which end the knotting started.

The pile of Anatolian carpets is usually between 2 and 4 mm deep. Coarser village or nomad carpets such as those of the Yörüken can be up to 12 mm deep. Sleeping carpets ( yatak ) have pile depths of 20 to 25 mm.

Origins and Traditions of Turkish Carpet Patterns

The pattern design of Turkish carpets integrates a wide variety of traditions. Specific pattern elements are closely related to the history of the Turkic peoples and their interaction with the surrounding cultures, both in their Central Asian regions of origin and during their migration to and in Anatolia itself. The main influences come from Chinese culture and from the culture of Islam . Carpets from the region around Bergama and Konya are now considered to be those that are most closely related to the old pattern traditions. Its importance in art history is better understood today.

Central Asian traditions

The early history of the Turkic peoples in Central Asia is closely linked to the history of China. Contacts between the Turkic peoples and Chinese civilization are documented by Chinese sources since the early Han dynasty . In his essay on "Centralized Designs", Thompson brings the central medallion pattern, which is often seen on Turkish carpets, particularly pronounced in Western Anatolian carpets with the "Ghirlandaio" medallion , in connection with the "lottery valley" and the " cloud collar ( yun chien ) “Motif of Buddhist Art . He dates this pattern back to the Yuan Dynasty . Brüggemann has further developed this research approach and even traces the motif back to the time of the Han dynasty. The “phoenix and dragon” motif of early Anatolian animal carpets also goes back to Chinese pattern traditions.

Roman-Hellenistic traditions

Ancient Greek sources already report carpets. Homer writes in Iliad XVII, 350 that the body of Patroclus was covered with a “splendid carpet”. In the Odyssey , books VII and X, he again mentions “carpets”. Pliny the Elder wrote in his Naturalis historia Book VIII, 48 that carpets ("polymita") were invented in Alexandria. It is unknown where the carpets mentioned come from and whether they were flat-woven or knotted carpets, because the texts do not provide any information about them.

Athenaios von Naucratis describes luxurious carpets around 230 AD in his book "Deipnosophistes (German: The Banquet of the Scholars)". The ancient city of Sardis , whose carpets are mentioned here, is located in western Anatolia near Izmir .

“And underneath these were purple carpets made of the finest wool, with the pattern on both sides. And there were nicely embroidered, nicely crafted carpets on it.

[...] to lie on a lounger with silver feet, with a soft carpet of sardis spread out underneath, as precious as you can imagine. "

A carpet “with the pattern on both sides” could either be a flat weave or a knotted carpet. It is not clear whether “purple” refers to the color of the fabric or the dye of the yarn. It could mean either Tyrian purple or madder red . In any case, Athenaios mentions carpet manufacture in an Anatolian city for the first time. Their description as precious luxury objects presupposes a long tradition and development of the craft.

Anatolia was founded in 133 BC. Ruled by the Roman Empire , later by the Byzantine Empire . The Eastern Roman and Sassanid empires coexisted for over 400 years. In the field of art, both empires have developed similar styles and decorative vocabulary, as exemplified in the mosaics and architecture of Roman Antioch . An Anatolian carpet pattern, depicted in Jan van Eyck's painting “Virgin and Child by Canon van der Paele”, was traced back to late Roman origins by Brüggemann and associated with very early Islamic floor mosaics in the Umayyad palace of Chirbat al-Mafdschar . The architectural elements of the Chirbat al-Mafjar building complex are viewed as exemplary for the continued existence of pre-Islamic, Roman patterns in early Islamic art.

Influence of Islamic art

When the Turkic peoples immigrated to Anatolia from Central Asia , they moved through areas that were predominantly Islamic. According to the strict interpretation of the Islamic prohibition of images , the visual representation of people or animals is not allowed. Since the codification of the Koran by ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān in the year 651 AD / AH 19 and the reforms of the Umayyad caliph ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān , Islamic art has focused particularly on decorative writing and ornament.

Kufic borders

The borders of Turkish carpets often contain ornaments that are borrowed from Islamic calligraphy . Usually, “kufic” carpet borders consist of entangled “lam-alif” or “alif-lam” sequences.

Geometric rows of ornaments

Some of the earliest known Anatolian carpets from Konya , Beyşehir and Fustāt as well as from the Divriği Mosque often feature patterns of repetitive geometrically constructed ornaments in an infinite repeat, for example rows of octagonal medallions that enclose four-pointed, eight-pointed stars between them.

Parallels to preserved architectural decorative elements of the Divriği Mosque and other Seljuk buildings in Sivas such as the Ulu Cami from 1196, the Mavi Medresesi from 1271, built by the Armenian architect Kaloyan, the Sifaiye Medresesi from 1218 and the Çifte Minare Medresesi from 1271, but also Armenian buildings such as the Armenian Palace of Ani , as well as their use in the decor of faience and in ornaments in book illumination, point to the universal importance of geometrically constructed ornaments in early Islamic art. While their origins may be found in Byzantine art, they were only further elaborated and completed by Islamic artists. Only in the "pattern revolution" of the 16th century did regular geometric patterns lose their meaning for the design of carpet patterns under the influence of Timurid and Persian art.

Infinite rapport

The fields of Turkish carpets, especially early ones, are often filled with repetitive, interconnected patterns in "endless rapport". The carpet field thus offers a section of a pattern that in principle continues under the borders into infinity. Anatolian carpets of the “Lotto” or “Holbein” type are examples of field patterns in the “infinite repeat”.

Prayer rug pattern

A specifically Islamic pattern is the mihrab pattern , which represents the niche in a prayer rug , which in every mosque shows the person praying the orientation towards Mecca ( Qibla ). The mihrab pattern of Anatolian carpets often appears modified and can have a single, double, or horizontally or vertically multiplied niche. A carpet with several niches lying next to each other is called a prayer carpet or "saf" .

The execution of the niche pattern can therefore range from a concrete, almost architectural conception to a more ornamental understanding of the pattern. Particularly in the course of the integration of the niche patterns of the court and city manufactories into the village or nomadic pattern tradition, a process of stylization can be demonstrated for the prayer rug pattern.

Prayer rugs are often knotted from the top of the prayer niche to the bottom of the rug. If you run your hand over the carpet to determine the line of the pile, this can be seen well. Probably this procedure has both technical (the weavers can initially concentrate on the more complicated niche pattern and later adjust the more technically feasible sections) as well as practical reasons: the pile tilts in the direction in which the person in prayer throws himself to the ground, which is feels more comfortable.

Other influences

Large, geometric shapes come from the Caucasian or Turkmen tradition. Caucasian patterns could have found their way into the pattern repertoire either through migrating Turkish tribes or due to contact with Turkmen peoples who already lived in Anatolia.

A central medallion made of geometric, concentrically shrinking diamond shapes with rows of hooks is associated with the Yörüken nomads of Anatolia. The name Yörük is usually given to those Turkish nomads whose way of life differs the least from the Central Asian customs of the Turkic peoples, but is not defined ethnically.

In Anatolia, various ethnic minorities, for example the Greeks , Armenians and Kurds, have retained their cultural characteristics under the Turkish government . While Greeks and, above all, Armenians played an important role in carpet production in the past, it is currently not possible to link certain carpet patterns with their independent, Christian tradition. A detailed analysis of the carpet patterns in comparison with Armenian book illustrations and ornaments of the Armenian fine arts was presented in 1998 by V. Gantzhorn. Kurdish carpets follow an independent tradition and are assigned to the Persian carpets .

Social context: court and town manufactories, villages and nomads

Carpets were made at the same time by and for the four different social classes of the ruling court, the city, the rural village and the nomadic population. Elements of urban or manufacturing patterns were often adopted from rural handicrafts and found their way into the artistic tradition of village weavers and nomads. This appropriation of patterns took place in an active process called stylization.

Hofmanufaktur

Carpets, which were supposed to meet the representational needs of the ruling court, were mostly produced by specialized manufacturers that were often founded and sponsored by the sovereign. In order to illustrate power and status, representative “court carpets” developed a special design tradition that was influenced by the patterns of neighboring countries and their rulers. Carpets were made in the court manufactories as special commissioned work or as precious gifts. Their sophisticated patterns required a division of labor between an artist, who was to design the pattern and set it out on a plan called a cardboard box, and knotters, who received the finished cardboard box for execution on the loom.

Town and village

Carpets were also made in smaller factories in the cities of the Ottoman Empire. Usually the city manufactories had a broader repertoire of patterns and ornaments as well as artistically elaborated templates that were then executed by knotters. The color palette is rich and the knotting technique could be finer because the city manufactories had access to better quality material and skilled, specialized professional knotters. Larger formats can be produced on the fixed, large looms. The carpets are knotted according to cardboard, the manufactory often also provides the professionally dyed material. City manufacturers were mostly able to make carpets to order even from other countries, or they produced carpets for export trade.

Carpet production in the villages was mostly done at home, here too sometimes to order and under the control of guilds or manufacturers. Working from home does not have to be full-time, but can always be carried out when time permits in addition to other duties. As indispensable household items for one's own use, village rugs are part of a tradition of their own, which at times was influenced by the design of the larger workshops, but basically existed independently. Village carpets were often given to the local mosque as a pious foundation , where they have stood the test of time and are now available for research. Rugs that were knotted in rural areas rarely contain cotton for warp and weft threads, and almost never silk, as these materials had to be purchased on the market.

Patterns and ornaments from court and town manufactories found their way into the repertoire of the smaller town or village workshops. This process is very well documented for Ottoman prayer rug designs. The design was subject to the process of stylization by adopting original court patterns from smaller workshops and passing them on from one generation to the next . This describes a series of small, step-by-step changes both in the overall design and in the details of smaller patterns and ornaments over time. As a result, a pattern can change so much and deviate from the original model in terms of design that it can hardly be recognized again. In the scientific tradition of the art history of the “Viennese School” around Alois Riegl , the process of stylization was seen more as the “degeneration” of a pattern. According to today's understanding, stylization means more of a real creative process within a separate artistic tradition.

Stylization using the example of the Anatolian prayer rug

Ottoman prayer rug from the court manufactory, Bursa, late 16th century (James Ballard Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art )

Tribes and nomads

With the end of the nomadic way of life in Anatolia in the 20th century, and as a result of the resulting loss of specifically nomadic traditions, it has become difficult to recognize a real “nomadic carpet”. Social or ethnic groups such as the Yörük or Kurds have adopted a largely sedentary lifestyle in Turkey today. Individual aspects of the tradition such as the use of special materials, colors, knotting techniques or the treatment of the edges and ends of the carpet may have been preserved and can then be viewed as “nomadic” or assigned to a certain tribe.

Characteristics of nomadic production are:

- Unusual materials such as goat hair warp threads or camel wool in the pile;

- High quality wool with a long pile;

- small format as it fits on a horizontal loom;

- irregular format due to the frequent assembly and disassembly of the loom, which leads to uneven tension of the warp threads;

- pronounced abrash ;

- longer flat weaves than finishes.

The most "authentic" products of the villages and nomads are those that have been made for their own use and not intended for export or local trade. This also includes special bags and upholstery covers ( yastik ), the patterns of which are often derived from the oldest knotting traditions.

Regions

Anatolia is divided into three large geographical regions, the traditional carpet production of which differs in its characteristics. Carpet weaving focuses on local cities and trading centers, after which the carpets produced in their area are named. West, Central and East Anatolia have different technical, pattern and color traditions. Due to the inner-Anatolian migration and the adoption of patterns and colors that are successful on the market through commercial production that is independent of traditions, modern carpets can often no longer be assigned to a specific city or region, but only roughly to one of the three geographical regions. Older and antique carpets, on the other hand, can often be assigned to a special knotting center due to the materials and colors used, technical properties and a characteristic pattern.

In general, Anatolian carpets differ from other oriental carpets in that they more often have primary colors. The most common colors used in Western Anatolia are blue and red, while Central Anatolia is more likely to use red and yellow. Sharp contrasts are achieved by knotting in white wool.

Regional technical characteristics

| Western Anatolia | Central Anatolia | Eastern Anatolia | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chain | Wool, white | Wool, mostly white, sometimes brown | Wool and goat hair, white and brown |

| shot | Wool, dyed red, sometimes brown and white | Wool, colored brown, white, red or yellow | Wool, mostly brown, sometimes dyed blue |

| Number of weft threads | 2-4 or more | 2-4 or more | 2-4 or more |

| Layered chain | No | sometimes | No |

| Margins | Shot reversal, mostly red, sometimes other colors | Weft reversal, red, yellow, other colors | Weft reversal, polychrome, "zipper" -like edge fastening |

| degrees | Kilim finishes , red or polychrome stripes | Kilim, red, yellow, polychrome | Kilim, brown, red, blue striped |

| Colours | Use of carmine, blue, white accents | no carmine, yellow | Carmine |

Western Anatolia

Typical western Anatolian carpets have a light brick red and lighter red tones. White accents are common, green and yellow are used more often than in other Anatolian regions. The warp threads are often colored red. The sides are reinforced with three to four warp threads. The ends are often protected by wide bands of flat weave, into which a small ornament made of pile is sometimes knotted.

- Istanbul is the capital and largest city of Turkey. During the 19th century, the court manufactories of Topkapı, Üsküdar, and Kum Kapı produced silk carpets with "Ottoman-Safavid" patterns based on the model of the Persian carpets of the 16th century. Persian and Armenian weavers (from the areas around Kayseri and Sivas) were often involved. Kum Kapı was the Armenian quarter in Istanbul in the 19th century. Asymmetrical knots were used, the silk carpets often have silver and gold threads woven into them. The two most famous carpet pattern designers were Zareh Penyamian and Tossounian. Zareh is known for his prayer rugs, the mihrābnic of which often have the "sultan's head" shape, bands of clouds in the field, as well as palmettes, arabesques and Koran inscriptions . Zareh also often signed his carpets. Tossounian made high-pile silk carpets with shiny colors and red flat-weave ends. The patterns of his carpets are inspired by the Persian "Sanguszko" carpets. The colors are very carefully chosen, carmine red, jade green, yellow, and an intensely bright dark indigo.

- Hereke is a coastal town 60 km from Istanbul on the Bay of İzmit . A knotting workshop was built here by Sultan Abdülmecid I in1843. Originally she only produced for the Ottoman court, which commissioned carpets for the newly built Dolmabahçe Palace . Carpet production began in 1891, and master weavers from Sivas , Manisa and Ladik were hired for this. Hereke rugs are best known for their fine weave. Silk and fine wool threads were used, and occasionally gold, silver or cotton threads. Hereke farm rugs show a variety of colors and patterns. The medallion patterns of the older Uşak carpets were used again. Originally the term "Hereke" carpet only referred to the products of the court manufactory, but today it has become a trade name for luxurious carpets of this type.

- Bergama is the capital of the district of the same name in the province of Izmir in northwestern Turkey . As a marketplace for the surrounding villages, the name Bergama is also used as a trade name. The history of carpet weaving in Bergama probably goes back to the 11th century. Bergama carpets from the 15th century have been preserved, the patterns of which were knotted with minor changes until the 19th century and give the carpets a particularly archaic character. The best-known type of carpet that was knotted in Bergama for export is the so-called large-patterned "Holbein" carpet, or Holbein type III. A pattern derived from this at a later date is the “4 + 1” or “Quincunx” pattern, with a large square central medallion surrounded by smaller square medallions at the corners. The antique Anatolian carpets of the "Transylvania" type were also at least partly made in the Bergama region. Bergama carpets usually have large geometric ("Caucasian") patterns, or more floral, rectilinear patterns (the "Turkish" type). Carpets from the Bergama region use the typical West Anatolian color schemes with dark red and blue and white accents. The so-called bridal carpets ("Kiz Bergama") often have rosette patterns arranged in a diamond shape in the field. Village and peasant carpets from the Bergama region are often knotted in a coarser weave with strong, strongly stylized patterns in bright blue, red and white tones in sharp contrast.

- The village of Kozak is located north of Bergama in the province of Izmir in northwestern Turkey. According to their structure and colors, they belong to the group of Bergama carpets. Rugs of rather small format show geometrical patterns, often with rows of hooks, which are similar to Caucasian patterns.

- Yagcibedir is not a name of a place, but a brand name for a type of carpet that is knotted in the province of Balıkesir in the Marmara region . These carpets are characterized by their high knot density (1000–1400 / m²) and the muted colors. Geometric patterns in dark red, brown and black blue are similar to those of Caucasian carpets. In fact, Yagcibedir carpets are mostly knotted by people of Turkmen or Circassian origin who immigrated to this area a long time ago.

- Çanakkale is located on the east bank of the Dardanelles near ancient Troy . Carpets are mainly made in small villages south of Çanakkale. They show large square, diamond-shaped or polygonal pattern elements in powerful colors such as brick red, bright dark blue, saffron yellow and white. Ayvacık is a small town south of Çanakkale and Ezine , near the ruins of Assos and Troy. The carpets are also of the Bergama type. The DOBAG Initiative has been running workshops in the small hamlets around Ayvacıksince 1981, where they produce carpets with traditional patterns using naturally dyed, hand-spun wool. The initiative also has a production facility in the Yuntdağ area near Bergama. There, peopleof Turkmen descent weave robust, thick carpets, mostly with geometric patterns. Floral or prayer rug designs are rarely found.

- The area around Balıkesir and Eskişehir is predominantly inhabited by a Turkish tribe, the Karakecili. Their carpets are often small, with a cheerful bright red, light blue, white and pale green. The use of goat hair in the warp threads indicates originally nomadic tradition. The patterns are mostly geometric and often combined with stylized floral motifs. The borders sometimes show rows of diamond-shaped cartouches, which are similar to those in the more finely worked “ Transylvanian carpets ”.

- Bandırma is the capital of the province of the same name on the Marmara coast. Finely knotted carpets have been made there since the 19th century, predominantly in the prayer carpet pattern. The cotton ground and the fine knotting of wool and silk characterize the carpets from Bandırma as products of the city manufactory. In the course of the 19th century production slowed down and the use oflower quality silk, rayon, or mercerized cottonbecame more common. The name of the city and region is often used today to denote cheap imitations that do not necessarily have to be local.

- Gördes is about 100 km northeast of Izmir . Carpets were already being knotted there in the 16th century, the most valuable ones from the 18th century. The mass production that began in the 19th century has no artistic value. Their predominantly floral, stylized patterns go back to Ottoman patterns of the 16th and 17th centuries. The main border often features strung bundles of three pomegranates that appear to be bundled on their stems. A widebordermade up of seven strips ( sobokli )is also typical. Gördes is particularly known for its bridal and prayer rugs. The shape of the mihrab niches varies from simple stepped arches to artistically sophisticated architectural pillars and arches, often with a horizontal rectangular beam above the niche. The tip of the Geibels is often accentuated by a stylized shrub. Typical colors are cherry red, pastel pink, blue and green along with dark indigo blue. Older Gördes carpets have more vibrant colors. From the 19th century, larger accents can also be found in white cotton, and the colors become more muted overall. In the second half of the 19th century, the patterns from Gördes were popular models for the Bursa and Hereke factories, often knotted in silk; cotton is used extensively in late pieces. Imitations of the Gördes pattern can also be found in carpets from Tabriz.

- Kula is the capital of the Manisa province, about 100 km east of Izmir on the road to Uşak. Together with Ușak, Gördes, Lâdik and Bergama, Kula is one of the most important centers of carpet production in Anatolia. Often there are prayer rug patterns with straight mihrab niches. Another special regional pattern is the " mazarlik ", or cemeterypattern, a special type of garden pattern. Its particularly dark but intense color scheme gave a type of carpet from the region the name "Kömürcü (Köhler) Kula". The combination with predominantly yellow borders is characteristic of Kula carpets. Quite unusual for Anatolian carpets, even for oriental carpets in general, flax fibers are usedfor the warp and weft of the “Kendirli” -Kula.

- Uşak is located north of Denizli in the Aegean region . The region is one of the most famous and important carpet centers. According to structure and pattern, a distinction is made between different types such as the “star” and “medallion” usaks as well as the “white-ground” carpets from nearby Selendi. Ușak carpets were often depicted in Renaissance painting and were often named after the painters who depicted them in their pictures. The best known are the carpets of the "Holbein" and "Lotto" types.

- Smyrna carpets are knotted in the area around the city that is now called Izmir. The products from Smyrna differ from other Anatolian carpets by their finely worked, curvilinear "urban manufacture pattern". Individual ornaments show a direct relationship to the Ottoman "court manufactory carpets". The main border in particular often shows the elongated cartouchesknownfrom Transylvanian carpets .

- Milas is located on the southwestern Aegean coast . Prayer rug patterns with characteristic indented mihrabs, mostly with a plain brick-red background, have been knotted here since the 18th century. The gusset is usually in a beige tone. Most of the carpets from this period have a wide border in which eight-sided rosettes alternate with symmetrical, stylized palmettes on a light yellow background, which are framed by lancet leaves. Other carpets from the region are the so-called “Ada” (island) Milas carpets from the area around Karaova, with vertically warped polygons in the field, and the rare “Medaillon Milas” carpets with a mostly golden yellow medallion on a red background. In the borders you can often see crystal-like star patterns composed of arrow-like ornaments that point towards the center, similar to Caucasian carpets. Common colors are pale purple, a warm yellow, and pale green. The field is often brick-red in color.

- Megri is located on the Turkish south coast across from the island of Rhodes . In 1923 the name of the city was changed to Fethiye. The field of Megri carpets is often divided into three different, long fields with floral patterns in them. Prayer rug patterns with stepped gable ribbons occur. Typical colors are yellow, light red, light and dark blue and white. Megri carpets are also sold under the trade name Milas. Sometimes it is difficult to tell the difference between these two city manufactory products.

- The city and province of Isparta do not have a very long tradition of weaving. Local carpets tend to mimic Persian patterns. Their high pile and solid weave make the carpets particularly suitable for household use, which is why they are rarely exported.

Central Anatolia

Central Anatolia is one of the main carpet manufacturing regions in Anatolia. Regional knotting centers with specific patterns and traditions are:

- Konya (Konya, Konya-Derbent , Selçuk , Keçimuslu, Ladik, Innice, Obruk)

The city of Konya is the ancient capital of the Seljuk Empire . The Mevlana Museum in Konya has a rich collection of Anatolian carpets, including the carpet fragments from the Alaaddin and Eşrefoğlu mosques. Carpets from Konya often have a finely worked prayer rug pattern, with a monochrome field in bright madder red . Konya-Derbent carpets often feature two floral medallions in the field below the mihrab niche. The traditional Konya-Selçuk pattern uses narrow octagonal medallions in the center of the field, with three opposing geometric shapes topped by tulips. Another typical feature is a wide ornamental main border with detailed, filigree patterns that are flanked by two side borders that show the very old pattern of meandering tendrils and flowers. Carpets from Keçimuslu are usually sold under the trade name Konya and also show a similarly bright madder-red field, but the color of the main border is usually green.

Konya Ladik rugs also often have the prayer rug pattern. The field is mostly in light madder red, the mihrab niche is stepped. Opposite, sometimes directly above the niche, there are smaller gable patterns. These are often arranged in groups of three, with each pediment decorated with stylized, geometric tulip ornaments. Often the tulips are arranged upside down at the lower edge of the mihrab niche. The gable arches of the niche are often colored golden yellow and show water jug ( ibrik ) ornaments. The “Ladik sinekli” patterns are also typical of the Ladik region: on a white or cream-white field there are many small black ornaments that are reminiscent of flies (Turkish: “ sinek ”). Carpets from Innice are very similar to Ladik carpets with their tulip ornaments and the strong red field with complementary green arches. Obruk carpets have the patterns and colors typical of Konya, but the ornamentation is coarser and more stylized and thus point to the Yörük tradition of the villagers. Obstruc carpets sometimes come onto the market in Kayseri.

Carpets from Kayseri are characterized by their fine weave, a hallmark of the manufacture that is common in this area. Carpets are mainly knotted for export and often imitate patterns from other regions. Wool, silk and rayon are used. The top products from Kayseri often come close to those from Hereke and Kum-Kapı. Urgup, Avanos and İncesu are cities in Cappadocia .

Avanos carpets, often with a prayer mat pattern, are characterized by their dense weave. The field is often decorated with a very finely drawn ornament in the form of a mosque lamp or a triangular protective amulet (" mosca "), which hang down from the top of the niche. The prayer niche itself is often graduated or drawn in on the side in the classic "head-and-shoulder" shape. Often the field is bright red and surrounded by golden yellow gable fields and borders. The fine to very fine weave allows for a very sophisticated pattern design, by means of which Avanos carpets can be easily recognized.

Ürgüp carpets have a special color scheme. Golden brown often dominates, light orange and yellow are often seen. A locket within a locket is often in the field. This is held in the typical "Ürgüprot" and decorated with floral motifs. Palmettes fill the corner medallions and borders. The outermost side border often has a reciprocal crenellated pattern.

Carpets from Kırşehir, Mucur and Ortaköy are closely related and not easy to distinguish from one another. Both prayer niche and medallion patterns appear, as well as garden (“ mazarlik ” or “cemetery”) patterns. Pale turquoise blue, pale green, and pink are the predominantly used colors. Ortaköy carpets show a hexagonal central ornament, which often encloses a cross-shaped pattern. In the borders you can see stylized carnations arranged in a row of square frames. Carpets from Mucur, which only gained importance as a knotting center in the 19th century, have a stepped, unpatterned "prayer niche in the prayer niche" pattern in contrasting, bright madder red and light indigo blue, set off from one another by yellow outlines. The characteristic border design of Mucur consists of tile-like rows of squares, the individual motif of which is a diamond standing on top with a central eight-leaf rosette. Two V-shaped filling motifs in each corner complement the area around the diamond to the square. The colors of the Mucur carpet are intense, but cooler and can appear restless in the frequently used combination of medium blue, green, dirty yellow and purple of the border. Mucur and Kırşehir are also known for their row prayer rugs (" saph ").

Niğde is the market center for the area. If a prayer niche pattern is used, niches and arches are typically very narrow. The field is also often not much wider than the main border. In the field of Taşpınar carpets, one very often sees an elongated, almost oval central medallion. The dominant colors are warm red, blue, and light green. Fertek rugs are characterized by their simple floral ornaments. The field is often not, as is usually the case, delimited from the main border by means of a narrow secondary border. The outermost secondary border often has a reciprocal battlement pattern. The colors are composed of soft red, dark olive green and blue. Maggot carpets use cochineal red in the narrow fields that are also characteristic of Niğde carpets. A corrosive brown is often used as the basic color of the main border, which over time attacks the wool of the pile and creates a relief effect due to the increased wear on the areas colored in this way. Yahali is also a regional center and marketplace for the area. Carpets from here show hexagonal medallions with double hook ornaments in the fields and carnation ornaments in the main border.

Karapinar and Karaman belong geographically to the Konya area, but the carpet patterns are more closely related to the Niğde region. The pattern of the Karapinar carpets shows similarities to Turkmen door carpets (" ensi "), but comes from a different tradition. Three columns crowned by double hooks (" kotchak ") form the prayer niche. Opposite “double hook” ornaments fill the pillars in Karapinar and Karaman carpets. Another type of pattern that often occurs in Karapinar runners is composed of geometric hexagonal primary motifs arranged one above the other, in muted red, yellow, green and white.

State-run workshops, some of which have been developed as carpet weaving schools, produce the carpets from Sivas. The patterns imitate those from other regions, especially Persian patterns here. Traditional Sivas carpets are characterized by their dense, short-sheared, velvety pile in the sophisticated pattern design of the "Stadtmanufaktur". The main border often shows ornaments in rows of three carnation flowers on connected stems. Zara, 70 km east of Sivas, has Armenian settlements that make carpets with a pattern of multiple rows of vertical stripes that span the entire field. Each strip is decorated with finely crafted floral arabesques. The pile is sheared very short so that the detailed pattern is clearly visible.

Eastern Anatolia

Specifically Eastern Anatolian patterns are not known. Until the Armenian genocide in 1915, Eastern Anatolia had a large Armenian population. Occasionally, it is possible to identify a carpet as Armenian from a knotted inscription. Unfortunately, there is also no precise information on Kurdish and Turkish carpet weaving in the region. Research from the 1980s concluded that the tradition of carpet weaving in Eastern Anatolia was almost extinct, and more detailed information about the Eastern Anatolian patterning traditions was probably lost.

- Kars is the capital of the province of the same name in northeast Anatolia. In the area around the city, carpets are produced that are very similar to the Caucasian ones, with slightly more muted colors. The name "Kars" also serves as a trade name and then refers to the quality of the knot. Lower quality carpets from the region are sometimes referred to as "Hudut" (literally "border") carpets. These were mostly made in the border region between Turkey, Iran, Armenia and Georgia . Kars carpets often have "kasak" patterns, as seen in the Caucasian Fachralo, Gendsche, and Akstafa carpets, but their structure and materials are different. Kars or Hudut carpets often contain goat hair in the pile and backing.

Other East Anatolian carpets are usually not assigned to a specific region, but are classified according to the tribe that made them. Kurds and Yörük tribes had lived as nomads for almost their entire history and therefore tended to make tribe-specific patterns rather than regional ones. In the event that a carpet with a general Yörük pattern can be assigned to a certain region (Yörük also live in other regions of Anatolia), the name of the region is often preceded by the tribal name. A large Kurdish population lives in the areas around Diyarbakır , Hakkâri , and in Van Province . The cities of Hakkâri and Erzurum were market centers for Kurdish kilims , carpets and small-format knots such as cradles, bags ( heybe ) and tent decorations.

Galleries

Pattern of Central Asian origin: cloud ribbon, lotus seat, cloud collar

Patterns influenced by Islam: calligraphic borders, infinite repeats, prayer rugs

West Anatolian Lotto Carpet, 16th Century, Saint Louis Art Museum

Row niches - prayer rug (saph) in the Selimiye Mosque , Edirne

Row niches prayer rug (saph) in the Sultan Ahmed Mosque , Istanbul

See also

Web links

- Turkish Cultural Foundation: Turkish carpets and kilims, accessed November 30, 2015

- Weaving Art Museum website, accessed November 30, 2015

- Picture gallery, accessed on November 30, 2015

- Collection of classical Anatolian carpets of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (English), accessed on November 30, 2015

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Kurt Erdmann: Seven Hundred Years of Oriental Carpet . Bussesche Verlagshandlung, Herford 1966, p. 149 .

- ↑ a b c d Werner Brueggemann, Harald Boehmer: Carpets of the farmers and nomads in Anatolia . Verlag Kunst und Antiquitäten, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-921811-20-1 .

- ↑ Alois Riegl: Old Oriental carpets . Ed .: A. Th. Engelhardt. Reprint 1979. 1892, ISBN 3-88219-090-6 .

- ↑ a b Wilhelm von Bode: Near Eastern knotted carpets from ancient times . 5th edition. Klinkhardt & Biermann, Munich 1902, ISBN 3-7814-0247-9 .

- ^ The historical importance of rug and carpet weaving in Anatolia . Turkishculture.org. Retrieved January 27, 2012

- ^ Turkish Cultural Foundation. Retrieved June 29, 2015 .

- ↑ Çatalhöyük.com: Ancient Civilization and Excavation ( Memento of the original from January 1, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Catalhoyuk.com. Retrieved January 27, 2012

- ↑ Oriental Rug Review, August / September 1990 (Vol. 10, No. 6)

- ↑ Hermitage Museum: The Pazyryk Carpet . Hermitagemuseum.org. Retrieved January 27, 2012

- ^ The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art: The debate on the origin of rugs and carpets . Books.google.com. Retrieved July 7, 2012

- ^ William Marsden: Travels of Marco Polo, the Venetian: the translation of Marsden revised. Ed .: Thomas Wright. Bibliobazaar, Llc, [Sl] 2010, ISBN 978-1-142-12626-1 , p. 28 .

- ^ FR Martin: A History of Oriental Carpets before 1800 . Printed for the author in the I. and R. State and Court Print, Vienna 1908.

- ^ Rudolf Meyer Riefstahl: Primitive Rugs of the "Konya" type in the Mosque of Beyshehir . In: The Art Bulletin . 13, No. 4, December 1931, pp. 177-220.