Armenians in Turkey

The Armenians in Turkey ( Turkish Türkiye Ermenileri , Armenian Թրքահայեր Trkahajer even Թուրքահայեր Turkahajer , both meaning "Turkish Armenians") are for the most part the survivors of the Ottoman genocide of Christian Armenians from 1915 to 1917. Armenians are counted who have lived in the country since the founding of the Turkish state in 1923 by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk .

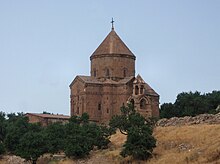

While they lived all over Anatolia before the genocide , today only an estimated 45,000 members live in Istanbul (around 75% of the Turkish-Armenian population), as well as a few in other cities. Only a few remains of the originally strong Armenian settlement in the country. The last still Armenian-settled village in Turkey is Vakif near Antakya , where survivors of the Musa Dagh stayed. Further north, on the island of Aghtamar in Lake Van near the city of Van , stands the now state-owned Church of Aghtamar , once one of the spiritual centers of historical Armenia . In this region, but also in central Turkey - mainly in the provinces of Van and Kayseri - an unknown number of so-called crypto - Armenians live , who do not reveal themselves to the outside world as Armenians. The Hemşinli should not be confused with these - Armenians who converted to Islam during the Ottoman Empire and who are Muslim today, mainly in the Erzurum province . In the past over 1.5 million Armenians lived in what is now Turkey, mainly in the east of the country, but today the total number is around 60,000, only a few of them outside the Istanbul region. Nationwide only 22 clergy are available. While there are 33 Armenian Apostolic , 12 Armenian Catholic and 3 Armenian Evangelical churches in Istanbul, only four Armenian Apostolic churches with a status as such remain in the rest of Turkey: in Kayseri ( Saint Gregory the Illuminator Church ), Diyarbakır ( St. Giragos Cathedral ), İskenderun and the village of Vakıflı in Hatay Province .

history

The Armenian people lived since at least the 7th century BC. In the Armenian highlands . The Armenian King Trdat III. (approx. 286–344) probably became a Christian in 314 and made Christianity the state religion in the same year.

For a long time the Armenian highlands were divided into western Armenia ( belonging to the Ottoman Empire ) and eastern Armenia ( belonging to Persia , later belonging to Russia ), but since the genocide of the Armenians it has been divided into regions to avoid the term “Armenian” or “Armenia” Eastern Anatolia or Transcaucasia (southern Caucasus region) assigned. Today all of western Armenia and parts of eastern Armenia (Kars, Ardahan, Igdir) belong to Turkey, while the rest of eastern Armenia forms the Republic of Armenia and parts of Azerbaijan as well as Nagorno-Karabakh .

Comparatively short phases of state independence of the Armenians alternated with foreign rule, among others, the Persians and the Romans or the Eastern Roman Empire . The Armenian Bagratid metropolis of Ani was occupied by Eastern Roman troops in 1045 and after it was conquered by the Turkish Seljuks under Alp Arslan on August 16, 1064, its population was wiped out. After the victory of the Sultan Alp Arslan over the army of the Eastern Roman Emperor Romanos IV in the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the way was clear for the Turkish conquest of Asia Minor. Armenian refugees from the subjugated motherland founded the Kingdom of Lesser Armenia in 1080 in Cilicia on the Mediterranean coast under the Rubenids , which, with the support of the Crusaders, was able to maintain its independence into the 14th century and where the seat of the Catholicos of All Armenians was now also located. A new settlement area for the Armenians was created here. The Cilician capital Sis became the seat of the Cilicia Catholic in 1293 and remained so after the Turkish conquest until the genocide in 1915. In 1375 the Mamluks took Sis, and in 1515 the former Little Armenia became part of the Ottoman Empire .

There was a split in the Armenian Apostolic Church in Cilicia in 1113, whereupon part of the clergy in opposition to the Catholicos Gregory III. Pahlawuni (1113–1166) moved his seat to the old monastery of Aghtamar with the Holy Cross Church (Surb Chatsch), appointed David I. Thornikian as a counter-Catholic and thus founded the Catholic of Aghtamar , which existed until 1915. Due to its close proximity to the main settlement areas of the Armenians around Wan , Bagesch and Musch , it had a greater influence on them than Sis.

In 1453 the last remnant of the Eastern Roman Empire fell with the metropolis of Constantinople . Shortly after the conquest in 1461, the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II (1432–1481) had the Armenian bishop of Bursa , Howakim, take over the leadership of the Armenian parish in the city. This established the Patriarchate of Constantinople of the Armenian Apostolic Church .

Through the Islamization under Turkish rule as well as through emigration first to Cilicia and later to Europe, the Armenians became a minority in their old settlement areas. Nevertheless, until the Great Genocide, they formed a significant minority in many cities and a local majority in some places, and there were numerous Armenian villages.

Within the framework of the Millet system , the Armenian Apostolic Christians were recognized as one of three non-Muslim denominations (milletler, singular millet) alongside the Orthodox faith nation under the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople (especially the Ottoman Greeks ) and the Jewish faith nation. The Syrian Orthodox Church of Antioch has long been assigned to the Armenian Millet and was not recognized as a religious nation of its own until 1873, while this was granted to the Syrian Catholics in 1829 and the Chaldeans in 1846. The “book religions” were protected on the basis of Sharia law, but were subject to discrimination . This concerned, for example, the value of testimony in court and the law of inheritance, but also the ban on carrying weapons. A poll tax ( cizye ) had to be paid for the status of protected person ( zimmi ).

In the Ottoman Empire, the Armenians had a reputation as a "loyal nation of faith" (millet-i sadika) , which enabled many to rise to high positions. The architects of both the Dolmabahçe Palace of the Ottoman sultans and the Ortaköy Mosque, for example, came from the respected Armenian Balyan family in the 1850s .

In addition to the Armenian town of Zeytun , the remote region of Sasun in Sanjak Mush in Vilayet Bitlis was an exception with regard to the possibilities of the native Armenians to maintain relative autonomy. The inhabitants of the 40 or so Armenian villages, known as Sasunzi ( Armenian Սասունցի , plural Sasunziner Սասունցիներ ), stood economically on their own two feet and also made their own weapons - contrary to the theoretical prohibition - and defended themselves against attacks by neighboring Kurdish tax collectors. The Armenian national epic David von Sasun , recorded in 1873 by Bishop Garegin Srvandztiants , also comes from this area . Autonomy ended at the end of the 19th century when the Kurdish neighbors were also forced under the control of the government. With the increasing loss of power of the Ottoman Empire, the Armenians' aspirations for autonomy were seen as a threat. The refusal of the Sasunziner to pay double taxes to Turks and Kurds, the government used in 1894 as an opportunity to deploy military supported by Kurdish volunteers and shoot at the Armenians, against which the farmers of Sasun offered armed resistance . At the same time, the Armenians in Zeytun organized their self-protection . The following massacres of the Armenians from 1894–1896 by Kurds and Turks killed several thousand Armenians in Sasun and over twenty villages. In total, around 200,000 Armenians died from the massacres under Abdülhamid II, who ruled from 1876 to 1909 , while others left the country in large numbers. In 1904, in Sasun, the Armenian resistance to tax collection was broken again with armed force. Even after Abdülhamid's fall, the Adana massacre occurred again in 1908 , which was branded as Adanayi voghperk in the collective memory of Armenian communities around the world.

In 1867, based on surveys it had carried out in previous years, the Ottoman government put the number of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire at around 2.4 million. The census on the eve of the First World War in 1914, on the other hand, showed only 1,225,422 Armenians, but 13.4 million Muslims out of a total of around 20 million inhabitants. The Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople determined a number of 1,914,620 members of the Armenian Apostolic Church, i.e. Armenians, in the Ottoman Empire on the basis of its church records and baptismal registers in 1913.

From the 1890s to 1915, three Armenian parties in particular were important in the political life of the Ottoman Empire: the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF, Daschnag), the Social Democratic Huntschak Party (Huntschak) and the Armenakan Party, later the Democratic-Liberal Party (Ramgawar) . After the destruction of the Armenian community of the Ottoman Empire, these parties continued their activity in the Armenian diaspora and played an important role especially in the Armenian community in Lebanon , but now also in Armenia and the Republic of Artsakh . In today's Republic of Turkey, however, the establishment of ethnically based parties is not permitted.

During the First World War , most of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire became the target of a policy of brutal massacres and bloody deportations organized by the Ottoman government of the Young Turks and known as the genocide of the Armenians and by the approximately 800,000 to 1.5 million Armenians died. At the end of the war, the Ottoman Empire was defeated by the Allies. Hopes of the Armenians to return to an independent Armenia in the historical settlement areas in what is now northeastern Turkey, provided for by the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, were however given by the military victories of the Turks under Ataturk and the defeat of the Democratic Republic of Armenia in the Turkish-Armenian War as well as in the Treaty of Kars smashed the border between Soviet Russia and the newly founded nation-state Turkey . The Treaty of Lausanne 1923 provided for the Armenians who remained in Turkey, on the basis of religious affiliation, not only legal equality but also at least minority rights such as the right to practice the Christian religion, Armenian schools and publications in the Armenian language.

Nevertheless, there was still the destruction of Armenian cultural assets such as churches and schools as well as a policy of Turkishization - especially in the former six Armenian vilayets . Surviving Armenians had to settle abroad and formed an Armenian diaspora there . Others stayed and denied their origins as “secret Armenians” (Gizli Ermeniler) or so-called “ crypto-Armenians ” (Kripto Ermeniler) . Any Armenian and non-Muslim, later also other non-Turkish place names were changed to Turkish names . Even after the genocide, Armenian cultural assets and lands were expropriated over the decades . In 1923 an economic congress in Izmir (İzmir İktisat Kongresi) decided to specifically support Turkish entrepreneurs and to mobilize capital from non-Muslim citizens or “inner strangers” (içimizdeki yabancılar) . In violation of the Treaty of Lausanne, very high special taxes were levied on non-Muslims, for example the Varlık Vergisi wealth tax , which was valid until 1944 , which amounted to 5% for Muslims and over 50% for non-Muslims and thereby ruined the economic existence of numerous Armenians and Greeks. In the course of the Cyprus crisis , nationalists organized the pogrom in Istanbul in 1955 , which particularly affected the Greeks, but also Armenians and Jews. Because of this, from 1955 to 1980, in addition to almost all Greeks in Istanbul, tens of thousands of Armenians also left Turkey. In addition, a large number of the few Armenians who remained in the former western Armenia gradually moved to Istanbul, where the only living Armenian community existed and thus opportunities to live as Armenians in Turkey. Even after 1970, property from Armenian institutions was expropriated on a large scale, including the Tuzla Ermeni Çocuk Kampı children's home with 1,500 children, where the later editor-in-chief of Agos , Hrant Dink , and his wife worked, which was closed by court order in 1984 and has been vacant since then . Bureaucratic harassment and attacks by nationalists make life difficult for the communities of the Armenians and other Christian minorities in Turkey.

In 1975, the Armenians in exile founded the Armenian underground organization Asala in Beirut , which until 1991 carried out a series of attacks on Turkish diplomats with a total of 46 fatalities and 299 injured. Although connections between the Asala and Armenians in Turkey could never be proven, the state stepped up against Armenians. As a result, Turkish nationalists carried out attacks on Armenian institutions in Turkey and issued threats. After losing the base of operations in Beirut to the Israeli invasion, the Asala carried out an attack on Ankara-Esenboğa airport on August 7, 1982 , killing 9 people and injuring 70. As far as is known, the attacks were very unpopular among the Armenians in Turkey. The Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink said on November 2, 2005 that Turkish Armenians walked around with their heads hanging down during the Asala period. The Turkish Armenian Artin Penik self- immolated himself on August 10, 1982 in Taksim Square in Istanbul after the attack on Esenboğa Airport, where he died five days later from the burns. The only surviving assailant of the Asala airport attack, Levon Ekmekjian , was sentenced to death by a military court in September 1982 and hanged on January 30, 1983 in Ankara . The German historian and journalist Jürgen Gottschlich regards the attacks in Asala as the main reason why the denial of genocide in Turkey remained unquestioned for many years.

The Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink founded the weekly Agos in Istanbul in 1996 together with Luiz Bakar, Harutyun Şeşetyan and Anna Turay , which addresses topics of the Armenians in Turkey and which appears partly in Armenian, but mostly in Turkish. In contrast to the Armenian-language newspapers Jamanak and Marmara , which are still published to this day, topics that had previously been taboo were now openly discussed, also in the Turkish language and thus in the Turkish public. In his articles, Hrant Dink advocated reconciliation between Turks and Armenians, human rights and minority rights in Turkey. He criticized both the denial of the Armenian genocide by the Turkish government and the campaign by the Armenian diaspora for international recognition of the genocide. Hrant Dink has been tried three times for " insulting Turkishness " ( Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code, which the EU has long been demanding to be deleted) and was convicted once, at the same time as receiving numerous death threats from Turkish nationalists. On January 19, 2007, he was shot dead in front of his newspaper building by 16-year-old contractor Ogün Samast . The murder of Hrant Dink triggered a very large wave of solidarity among Turks and Armenians in Turkey for the first time. Thousands of Turks protested against the murder on the evening of January 19, 2007 in Istanbul and Ankara and shouted in chants: “We are all Hrant Dink, we are all Armenians”. The murder was unanimously condemned in the Turkish press. More than 100,000 people attended Hrant Dink's funeral on January 23, 2007 and marched through the streets of Istanbul in protest. The Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk , winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature , pointed out that the Turkish government was partly responsible for the murder, which had made Hrant Dink an enemy of the state and thus a target. Like other Turkish intellectuals, he demanded the abolition of Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code, which is still valid today.

In December 2008, various Turkish journalists, professors and politicians launched the "I beg your pardon" ( Özür Diliyorum ) initiative , in which they called for an apology for the "Great Disaster" that the Ottoman Armenians were exposed to from 1915 to 1918. The campaign was also about the fact that Armenians were unable to speak openly about the events of 1915. By January 2009, 30,000 people in Turkey had signed. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan , however, declined an apology to the Armenians. The campaign, on the other hand, led to violent opposition and death threats against the signatories.

Of great importance in the relations of the Turkish government to the Armenians of the country has also the restoration of the Church of the Holy Cross (Surp Chatsch) on the island of Akdamar - the former seat of the Catholicosate of Aghtamar - which in 2005 by the Erdoğan government has been committed and Reopening when the church had also been repeatedly requested by Hrant Dink. On March 29, 2007, the Holy Cross Church, renovated with government funds of around 4 million YTL with the participation of the Turkish-Armenian architect Zakaryan Mildanoğlu , was reopened as a museum, but without a cross on the roof. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the Patriarch of Constantinople Bartholomew I and the Armenian Patriarch Mesrop Mutafyan as well as a delegation from the Armenian Ministry of Culture took part in the opening ceremony . The Catholicos of All Armenians, Karekin II. Nersissian , did not come despite the invitation, as the government had not fulfilled the request of the Patriarchate of Constantinople to reopen the church as such. On September 19, 2010, for the first time since 1915, a Christian service was held in the Holy Cross Church of Aghtamar, for which a cross from a museum in Van was placed in front of the church. Armenian believers from Turkey as well as from Armenia and the USA attended the mass, which was presided over by the Deputy Archbishop of Constantinople Aram Ateşyan . Aram Ateşyan said that ten years earlier neither such a service nor an open discussion about genocide and human rights was possible. At the beginning of October 2010 a 2 meter high and 110 kg heavy cross was placed on the roof of the Holy Cross Church and consecrated by the Armenian priest Tatula Anuşyan from Istanbul .

In the 2015 parliamentary elections , Armenians were re-elected to the Turkish National Assembly for the first time since 1961 , namely Garo Paylan for the HDP , Markar Esayan for the AKP and Selina Özuzun Doğan for the CHP .

Armenian press in Turkey

Two daily newspapers in the Armenian language appear in Istanbul : Marmara and Jamanak (founded around 1908), which is also the oldest daily newspaper in Turkey. In addition, the weekly Agos , founded by Hrant Dink , appears partly in Armenian, but mostly in Turkish.

Armenians in Istanbul

The Armenian community in Istanbul, numbered with 45,000 people (almost 75% of the Turkish-Armenian population), today has 33 Apostolic , 12 Catholic and 3 Protestant churches; 2 hospitals ( Surp Pirgitsch and Surp Agop ), 2 orphanages and 19 schools.

The Armenian Surp Pırgiç Hospital in Istanbul is one of the best in the country.

The Armenians of Istanbul live mainly in the districts of Pangaltı in Şişli and Kumkapı in the old town ( Fatih ). While the Armenians in Kumkapi, where the Patriarchate of Constantinople is also located, almost all belong to the Armenian Apostolic Church , the Armenians in Pangalti are partly in the Armenian Catholic or the Roman Catholic Church .

Armenians in Hatay Province

In the province of Hatay , there are two Armenian Apostolic churches, each with a church. After the First World War, the area became part of Syria and thus the French mandate area. When the area was first briefly declared Hatay state by Turkey in 1938 with the approval of the French and the other Western powers and then annexed in 1939, most Armenians emigrated as did the Arab Christians. Of the 7 villages on Musa Dagh , 6 emigrated as a group, while the residents of Vakif ( Vakıflı ) mostly stayed.

Most of the original residents of Vakif now live in Istanbul. The village has around 130 inhabitants in winter, all of them Armenians from Turkey, while in summer it has around 300 inhabitants, more than half of which are Armenians who are now living in Istanbul and who visit their homeland. The Church of Our Lady ( Armenian Սուրբ Աստվածածին եկեղեցի , Surp Asdvadzadzin ) in the village was restored between 1994 and 1997 with government support. Only occasionally does a priest come from Istanbul. The children of the village are mostly sent to Armenian boarding schools in Istanbul to have Armenian lessons, as there is no longer a school on site due to too few children.

İskenderun has a small Armenian church (Karasun Manuk) with a community of a few dozen Armenians.

Armenians in Kayseri and Diyarbakır

In the former western Armenia and central Turkey, there are now only two Armenian parishes with their own churches: in Kayseri the Church of Saint Gregory the Illuminator (Surp Krikor Lusaworitsch) and in Diyarbakır the St. Giragos Cathedral ( Surp Giragos). These congregations have very few members, as the Armenians either emigrated to Istanbul or abroad. Therefore, the Patriarchate of Constantinople has to send priests to worship services in these two churches at least once a year in order to meet the state requirement of a regular community life and not to be expropriated.

The St. Giragos Cathedral in the old town of Diyarbakır, already partially destroyed in 1915, was left to decay for years, but was reopened as a place of worship after renovation on October 22, 2011. During the Turkish offensive against the PKK in February 2016, the church was hit so badly by projectiles that parts of the roof and the outer wall collapsed. The church, like other buildings in the old town, was then expropriated and closed. In April 2017, the Turkish State Council (comparable to an administrative court) annulled the expropriation decision for St. Giragos because it violated the Treaty of Lausanne .

Crypto Armenians

After the genocide of the Armenians, numerous dispersed Armenians, including many orphans, stayed behind in the former western Armenia. Many were taken in by Turkish, Arab or Kurdish neighbors and thus saved. A large part grew up as Muslim Turks. In the absence of Armenian churches and clergymen, there is no way to live a Christian community life as an Armenian or even to carry out basic activities such as baptism or funeral. In many villages, however, entire families continue to live with the awareness of an Armenian identity without revealing this to the outside world. Many have moved to Istanbul over the decades because only there they can live openly as Armenians and practice Christianity in the Armenian churches.

These "secret Armenians" are also known as crypto- Armenians ( Armenian ծպտյալ հայեր , Turkish Kripto Ermeniler ) and must not be confused with the Hemşinli , who converted to Islam as Armenians during the Ottoman Empire . The Turkish historian Salim Cöhce, professor at İnönü University in Malatya , estimated in an article in the weekly newspaper Aksiyon in 2013 the number of crypto-Armenians in Turkey at around 37,000 families, of which 5,000 families in the province of Kayseri alone and 4,000 in the province of Van Familys.

Typically, the Crypto-Armenians form a small minority in the villages of the former Western Armenia, where they live among the Turks, Arabs and Kurds who immigrated to the area after the genocide. In the Argentine newspaper La Nación, however, an Armenian in Istanbul reported that his home village Arkint in Sasun still had around 400 inhabitants in 1965, including 250 Armenian Christians, 100 Islamized Armenians and 50 Muslim Kurds . Like the Sasunzines in earlier centuries, the residents were armed to defend themselves against Kurdish bandits who wanted to steal their wives. Up until the 1980s, Arkint was a predominantly Armenian village, until the residents sold their houses and emigrated to Istanbul, and in some cases further abroad.

Immigrants from the Republic of Armenia

Although Armenia and Turkey do not have diplomatic relations and the opinion of an “Armenian who works for a Turk” is very negative in Armenia in view of the very difficult relationship between the countries, there is immigration from Armenia to Turkey. The Armenians come to Turkey illegally as workers, which gives rise to better job and income opportunities. Istanbul, where there is an Armenian community and the best job opportunities, is the main destination for Armenian immigrants. Official Turkish estimates are between 22,000 and 25,000 Armenian illegals in Istanbul, and up to 100,000 in total. Many of them work in Turkish households as cooks or cleaners. A 2009 survey of 150 Armenian migrant workers found that most were women. In 2010, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan threatened to deport illegal immigrants to Armenia in view of the conflict over the recognition of genocide, but this has not yet been done. Some Armenian immigrants are determined to stay in Turkey. Due to the efforts of the Deputy Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople, Aram Ateşyan , the children of illegally immigrated Armenian parents in Istanbul were given the right to attend Armenian minority schools in 2011. However, since they are not Turkish citizens, they are not given any certificates. According to Aram Ateşyan, in the summer of 2011 there were around 1000 school-age children from Armenian immigrants who were supposed to go to Armenian schools.

Speech situation

The Armenian language in its western form , which differs from the Eastern Armenian language used by immigrants from the Republic of Armenia , is only spoken by a small percentage of Armenians in Turkey. While 82 percent of the Armenians only speak Turkish as their mother tongue among themselves and at home , Armenian is only predominant for 18 percent of the general population. The proportion is even lower among young people: while 92 percent speak Turkish as their mother tongue, only 8 percent speak Armenian. Turkish is increasingly taking the place of Armenian and it is believed that the once predominant Armenian language in Turkey will eventually become extinct over time . In Turkey, Armenian is defined as a language in clear danger and therefore viewed as threatened with extinction .

The dialect of the spoken by the hemshin peoples Armenian is the Homshetsi dialect .

Well-known Turkish Armenians

- Daron Acemoğlu - economist

- Hayko Bağdat - journalist

- Hayko Cepkin - musician

- Levon Panos Dabağyan - writer

- Agop Dilâçar - linguist

- Arat Dink - journalist

- Hrant Dink - journalist

- Markar Esayan - journalist and politician ( AKP )

- Ara Guler - photographer

- Rober Haddeciyan - writer, dramaturge and publisher

- Vartan İhmalyan - engineer and writer

- Cem Karaca (maternal side) - musician

- Rober Koptaş - journalist and historian

- Etyen Mahçupyan - journalist and policy advisor

- Mesrop Mutafyan - patriarch

- Garo Paylan - Teacher and Politician ( HDP )

- Adile Naşit (maternal side) - actress

- Aras Özbiliz - footballer

- Selina Özuzun Doğan - Lawyer and Politician ( CHP )

- Ruhi Su (very likely) - musician

- Arto Tunçboyacıyan - musician

- Garbis Zakaryan - sportsman

bibliography

- Béatrice Kasbarian-Bricout: Les Arméniens au XXe siècle. L'Harmattan, Paris 1984, ISBN 2-85802-383-X .

- Sibylle Thelen: The Armenian Question in Turkey. Klaus Wagenbach, 2011, ISBN 978-3-8031-2629-0 .

- Derya Bayır: Negating Diversity: Minorities and Nationalism in Turkish Law. London (PhD thesis: School of Law, Queen Mary University of London) 2010 ( PDF ).

- Bedross Der Matossian: The Armenian Commercial Houses and Merchant Networks in the 19th Century Ottoman Empire , in .: Turcica, 39, 2007, pp. 147–174.

- Dilek Güven: Nationalism and minorities: The riots against Christians and Jews in Turkey from September 1955. Munich, 2012.

- Tessa Hoffmann: Approaching Armenia. History and Present, Munich (2nd, updated and extended edition) 2006.

- Richard Hovannisian, Simon Payaslian (eds.): Armenian Constantinople. Costa Mesa CA, 2010.

- Mesrob K. Krikorian: Armenians in the Service of the Ottoman Empire 1860-1908. London, 1978.

Web links

- Mihran Dabag: The Armenian Community in Turkey. Federal Agency for Civic Education, April 9, 2014.

- Jaklin Çelik: My Armenian Istanbul. Federal Agency for Civic Education, April 26, 2016. German by Christina Tremmel-Turan and Tevfik Turan.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Foreign Ministry: 89,000 minorities live in Turkey ( Memento from May 1, 2010 in the Internet Archive ). Today's Zaman, September 29, 2008.

- ^ Robert W. Thomson: Mission, Conversion, and Christianization: The Armenian Example. In: Harvard Ukrainian Studies, Vol. 12/13 (Proceedings of the International Congress Commemorating the Millennium of Christianity in Rus'-Ukraine) 1988/1989, pp. 28–45, here p. 45

- ↑ Tessa Hofmann: Between Ararat and the Caucasus. A portrait of a small country in five key words. In: Huberta von Voss: Portrait of a Hope. The Armenians. Life pictures from all over the world. P. 24. Hans Schiler Verlag, Berlin 2004. ISBN 978-3-89930-087-1 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Mihran Dabag: The Armenian Community in Turkey. Federal Agency for Civic Education, April 9, 2014.

- ^ Robert H. Hewsen: Armenia: A Historical Atlas. University of Chicago Press, 2001. pp. 167, 206.

- ↑ Wolfgang Gust: The genocide against the Armenians. The tragedy of the oldest Christian people in the world . Munich / Vienna 1993, pp. 102-105, 121f.

- ^ A b Raymond Kévorkian: Les Armeniens dans l'empire Ottoman à la veille du génocide. Editions d'Art et d'Histoire, Paris 1992. pp. 53-56.

- ^ Stanford Jay Shaw, Ezel Kural Shaw: History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, Vol. 2: Reform, Revolution, and Republic. The Rise of Modern Turkey, 1808-1975. Cambridge 1988, pp. 239-241.

- ↑ TC Genelkurmay Baskanligi, Ankara. Arşiv Belgeleriyle Ermeni Faaliyetleri 1914–1918, Cilt I. Armenian Activities in the Archive Documents 1914–1918, Volume I. ( Memento of October 7, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (Census statistics 1914, PDF, editor: General Staff of Turkey , p. 609 .)

- ^ Hilmar Kaiser: Genocide at the Twilight of the Ottoman Empire. In: Donald Bloxham, A. Dirk Moses: The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies . Oxford University Press, New York 2010. S: 382.

- ^ Yasemin Varlık: Tuzla Ermeni Çocuk Kampı'nın İzleri ( Memento from December 6, 2006 in the Internet Archive ). BİAnet, July 2, 2001.

- ↑ Vatican Radio : Religious Freedom in Turkey-On the Situation of Christian Minorities in Turkey. ( Memento of October 16, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) 5. – 7. September 2004.

- ↑ Der Spiegel : Pope in Turkey - a visit to the 0.4-per mille community. ( Memento of June 7, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) November 28, 2006.

- ↑ Turkish daily Vatan in an interview with Dink, October 2, 2005 ( Memento from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Official Website of the Prime Minister, News, August 1982 ( Memento of April 14, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Turkey: A Cry for Bloody Vengeance. TIME, August 23, 1982

- ↑ Jürgen Gottschlich: Aiding and abetting genocide: Germany's role in the annihilation of the Armenians. Ch.links Verlag, Berlin 2015, p. 286.

- ↑ Dink was the voice of the Armenians in Turkey . Die Welt , January 19, 2007.

- ↑ Mass protest at editor's funeral ( Memento from March 12, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). The Guardian , Jan. 24, 2007.

- ↑ Hundreds expected at Hrant Dink's funeral . Wiener Zeitung , January 22, 2007.

- ↑ Susanne Güsten: Pamuk sees the mentality of lynching . Tagesspiegel , January 23, 2007.

- ↑ Özürr Diliyoruz FrontPage . Özür Diliyoruz. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ Turkey: Erdogan refuses to apologize to Armenians . In: Spiegel . Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ Robert Tait: Turkish PM dismisses apology for alleged Armenian genocide . In: Guardian , December 17, 2008. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ↑ Asli Aydintasbas: Should Turkey Apologize to the Armenians? . In: Forbes , December 26, 2008. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ↑ Mavi Zambak: The Armenian Church of the Holy Cross on lake Van reopened but only as a museum ( Memento of 29 September 2007 at the Internet Archive ), AsiaNews.it March 28, 2007, accessed on 29 March 2007

- ^ Armenian Church in Turkey reopened as a museum ( Memento from May 19, 2007 in the Internet Archive ). Neue Zürcher Zeitung , March 30, 2007.

- ↑ İşyerlerine Türkçe isim zorunluluğu geliyor ( Memento from September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ). Report of the Turkish newspaper Zaman from March 3, 2007.

- ↑ Akdamar Kilisesi'nin bu yılki restorasyon çalışmaları başladı ( Memento from September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ). Report of the Turkish newspaper Zaman from April 17, 2006.

- ↑ Armenia to send official team to church reopening ( Memento from September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ). Today's Zaman, March 16, 2007.

- ↑ Akdamar Kilisesi muze olarak açıldı. Newspaper article on cnnturk.com.tr, March 29, 2007.

- ↑ Van: Service in the Akdamar Church ( Memento from March 22, 2012 in the Internet Archive ). Report on www.trtdeutsch.com, September 14, 2010.

- ↑ Turkey allows first Armenian worship . Die Zeit , September 19, 2010.

- ↑ Akdamar Kilisesi'nin artık haçı var! ( Memento of October 3, 2010 in the Internet Archive ). Article of the Radikal of October 2, 2010.

- ^ Armenian Observers in Turkey's Parliamentary Election ( Memento of March 28, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). The Armenian Weekly, June 9, 2015.

- ↑ Ersin Kalkan: Türkiye'nin tek Ermeni köyü Vakıflı . Hürriyet , July 31, 2005.

- ^ Verity Campbell: Turkey. Lonely Planet , 2007. ISBN 1-74104-556-8

- ↑ Jürgen Gottschlich : The old man from Mosesberg. The daily newspaper , April 20, 2011.

- ↑ Iskenderun: Catholic Church - Katolik Kilisesi - Chiesa Cattolica - Catholic Church . In: anadolukatolikkilisesi.org . Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- ↑ Kayseri Surp Krikor Lusavoriç Ermeni Kilisesi Vakfı ( Memento from April 7, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Surp Giragos Kilisesi üç kavmin barış dualarıyla açıldı. Article in the Radikal of October 23, 2011 (Turkish)

- ↑ Roni Alasor, Anahit Khatchikian: Armenian Surp Giragos Church ready for Holy Mass ( Memento of April 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive ). Ararat News, October 18, 2011.

- ↑ Historic Armenian Church destroyed , kathisch.de, Feb. 15, 2016

- ^ Historical Armenian church in Diyarbakir destroyed , Kathpress , February 15, 2016.

- ↑ Why the Turkish government seized this Armenian church. ( Memento from April 14, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Al-Monitor, April 10, 2016.

- ↑ Ceylan Yeginsu: Turkey's Seizure of Churches and Land Alarms Armenians. New York Times , April 23, 2016.

- ↑ Uygar Gültekin: surreptitious expropriation in Sur. Agos , March 31, 2016.

- ↑ Sonja Galler: Assault on Diyarbakir's historic center: The city as spoils of war. Neue Zürcher Zeitung, April 18, 2016.

- ^ Turkey: expropriation of Armenian church halted. meconcern.org, April 6, 2017.

- ^ Turkey's Secret Armenians. ( Memento of February 13, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Al-Monitor, February 19, 2013.

- ↑ Türkiye'de, Araplaşan binlerce Ermeni de var ( Memento from May 1, 2013 in the Internet Archive ). Aksiyon, May 5, 2013.

- ↑ Avedis Hadjian: Huellas de los armenios secretos de Turquía. La Nación, February 10, 2013.

- ↑ Umut Uras: Armenian immigrants look for a better life in Turkey. Al Jazeera , April 20, 2015.

- ^ A b c Marianna Grigoryan, Anahit Hayrapetyan: Turkey: Armenian Illegal Migrants Put National Grievances Aside for Work. Eurasianet.org, September 2, 2011.

- ↑ Геворг Тер-Габриелян (Gevorg Ter-Gabrielyan): Армения и Кавказ: перекрёсток или тупик? In: Кавказское соседство: Турция и Южный Кавказ ( Memento from April 17, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ). Стамбул (İstanbul), 1. – 4. August 2008.

- ↑ Okan Konuralp: Ermeni çocuklar okullu olacak [Armenian children to be schooled]. Hürriyet , September 2, 2011.

- ↑ Children of Armenian irregular immigrants to attend community schools in Turkey. PanARMENIAN.Net, September 2, 2011.

- ^ Armenian immigrant children to be allowed in minority schools ( Memento of September 3, 2011 in the Internet Archive ). Today's Zaman, September 2, 2011.

- ^ Ruben Melkonyan: “Review of Istanbul's Armenian community history”. Panorama.am, September 29, 2010, accessed on December 14, 2010 (English).

- ↑ Tolga Korkut: UNESCO: 15 Languages Endangered in Turkey. Bianet.org, February 22, 2009, archived from the original on March 31, 2009 ; Retrieved October 31, 2009 .