Istanbul pogrom

The pogrom of Istanbul ( Greek Σεπτεμβριανά, "September events "; Turkish 6–7 Eylül Olayları , "events of September 6th to 7th") describes violent riots against the Christian , especially Greek minority in Istanbul , Izmir and the Turkish capital Ankara on the night of September 6th to 7th, 1955. Turkish Jews and Armenians also fell victim to the crimes .

Human Rights Watch suspects a state organization to be behind the mass riots, others assume this is certain.

While Turkish newspapers reported 11 deaths at the time, recent studies assume 15 deaths (including two Orthodox priests and an Armenian).

background

After the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans in 1453, the city's Greek population continued to grow. Under the rule of the sultans they played important roles in social and economic life as well as in politics and diplomacy. Even after Greece gained independence in 1829, nothing changed.

Encouraged by the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I , the Kingdom of Greece tried to implement the " Megali Idea " (Great Idea) by attacking the Ottoman Empire and starting the Greco-Turkish War with the aim of territories in Asia Minor and inhabited by Greeks To incorporate Eastern Thrace . After the defeat of Greece, a radical population exchange was agreed in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne : Almost all Christians (Greeks) living in Turkey, around 1.5 million people, were moved to Greece, and around 500,000 Muslims (Turks) had to leave Greece. Exceptions were on the one hand the Istanbul Christians ( Phanariotes ) and island Greeks, on the other hand the Muslims (including Pomaks , i.e. Bulgarian Muslims) in western Thrace .

After the Greco-Turkish War, both sides distrusted each other. The Istanbul Greeks, who were exempt from population exchanges, began to leave Istanbul.

causes

The causes lie partly in Turkish nationalism , which sprouted after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, and in the escalating Cyprus conflict . The population also experienced a falling standard of living due to falling prices for agricultural products on the world market, mismanagement and corruption. The popularity of the government under Prime Minister Adnan Menderes sank dramatically. The government also encouraged an escalation between the religions by turning away from the principle of secularism and wanting to establish an Islamic state. Menderes explained this as follows:

“We have freed our previously oppressed religion from oppression. Without paying attention to the cries of the obsessed reformists, we changed the call to prayer back to Arabic, introduced religious instruction in schools and allowed the Koran to be recited on the radio. The Turkish state is Muslim and will remain Muslim. Everything that Islam demands will be observed by the government. "

Historians and political scientists assume that the state participated in the planning of the pogrom and that the Cyprus conflict was deliberately hyped. Accordingly, the events hit the Greek community of Istanbul without any action on their part. The government of the time believed that it had found the scapegoat for the economic and political grievances.

Connection to the Cyprus conflict

The pogrom was intensified by the Cyprus conflict.

The Ottomans had to lease Cyprus to the United Kingdom in 1878 (see also History of Cyprus under British Rule ). In 1914 the island was annexed by British troops and declared a crown colony in 1925 . Already in 1878 tried Greek Cypriots the annexation of Cyprus to Greece, the so-called "under Archbishop Sophronios Enosis " (Greek .: Ένωσις) to enforce. During this period there were several revolts which were put down by the British occupation forces.

In April 1955, the "Greek-Cypriot National Organization of Cypriot Fighters", EOKA, launched an armed struggle against the British colonial forces stationed in Cyprus and the minority of the Cypriot Turks who had lived there since the Ottoman conquest . The movements "National Union of Turkish Students", "National Federation of Turkish Students" and "Cyprus is Turkish", founded in 1954, used the activities of EOKA in Cyprus to protest against the majority of Greeks and the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople .

In 1955, the Turkish government, supported by the Turkish press, tried again and again to incite Turks against Greeks in order to underline the seriousness of the Turkish claims on Cyprus. A few weeks before the events of 6/7. In September 1955, some Turkish politicians made anti-Greek speeches. On August 28, Menderes claimed that the Greek Cypriots were planning a massacre against the Turkish Cypriots.

course

On September 6, 1955, the Turkish radio reported that a bomb had exploded in the birthplace of the Turkish state founder Kemal Ataturk in the northern Greek city of Thessaloníki . The daily İstanbul Ekspres immediately printed a special edition entitled: “Our father's house was bombed”. The paper identified the Greeks as the culprits. Ataturk's birthplace was already a museum back then and was located on the premises of the Turkish consulate. Therefore, the research has meanwhile also spoken of a "bomb attack on the Turkish consulate".

The time of the assassination had apparently been chosen to torpedo the London tripartite conference that had been in session on August 29, 1955 and which had not yet concluded, which discussed the Cyprus conflict. The tripartite conference invited by the British government was intended to achieve peaceful coexistence between Greeks, Turks and British people who were pursuing their own interests in the Mediterranean region. However, during the conference, the British government tried to play the Greeks and Turks off against each other without escalating the situation through a military conflict between the two states. The pogrom interrupted the conference.

The Turkish Nobel Prize winner Orhan Pamuk reported in his book Istanbul: Memories of a City , the Turkish secret service was behind the action, while the World Council of Churches in Austria suspected “Turkish provocateurs” and reported that there was one in the garden of the Ataturk House A load of dynamite had exploded, but only property damage had been caused.

In Istanbul

The nationalist association Kibris Türktür Cemiyeti (English: Cyprus is Turkish ), founded at that time, distributed and sold the special edition of the Istanbul Express newspaper throughout Istanbul . The members tried to use the breaking news to make propaganda for themselves, to stir up excitement and to get the people behind them.

The pogrom itself was evidently planned well in advance, because the thugs, who had been incited by nationalistic and religious beliefs, came from far away on September 6th by various means of transport. This fact became clear, among other things, when after the excesses of violence at the Haydarpasa train station, the authorities placed looters who wanted to return to their hometowns İzmit and Adapazarı with their looted property . In addition, the leaders of the extremists had obtained up-to-date lists of the addresses of houses and workplaces of Christians weeks earlier.

Around 6 p.m., a train of allegedly 250,000 people began to maraud through the streets in Istanbul. Not only from outside thugs exercised violence, but also Istanbul citizens participated as helpers, perpetrators and followers. Muslim residents of Istanbul are said to have flagged their houses with the national flag that night to reveal to the marauding mob which house should be spared or which house they could attack. In some cases, the helpers of the pogrom had labeled houses “Not a Turk” to indicate that they were open for looting.

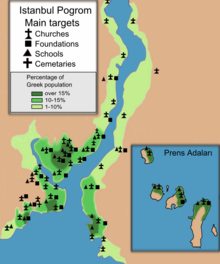

Murder, rape and gross abuse, including forced circumcision , went hand in hand with the destruction. There were also 32 seriously injured Greeks in Istanbul. Of the total of 80 Orthodox churches in and around Istanbul, between 60 and 72 were “more or less damaged” or set on fire. One of the damaged houses of worship was St. Mary, which the conqueror of Constantinople, Mehmed II , had given to his Greek architect Christodulos. In addition to the churches, more than 30 Christian schools were set on fire. Furthermore, the mob desecrated Christian cemeteries, the bones of the clergy, devastated around 3,500 houses, 110 hotels, 27 pharmacies and 21 factories and more than 4,000 to 5,000 shops and businesses. During the turmoil of the pogrom, businesses operated by Muslims were also attacked. When the riots against the minorities, the police either looked on inactive or tolerated them benevolently. The Ecumenical Patriarch Athinagoras I , head of Orthodox Christianity, held out in Phanar , which was besieged but not stormed.

The quick transport of the clubs within the city was ensured by cars, taxis, trucks and buses, but also by steamers and military means of transport.

In Izmir

Events similar to those in Istanbul took place in Izmir. The city governor Kemal Hadimil was later described as the initiator of the riots and is said to have been carried on the shoulders by local pogrom supporters. The aggression ended faster than in Istanbul, the center of violence.

In Ankara

In the Turkish capital, too, there were staged “spontaneous” outbreaks of violence against the Greek residents, but these were also brought under control more quickly than in Istanbul.

consequences

Damage

The total property damage caused is quantified differently:

- Turkish government agencies: 69.5 million Turkish lira (24.8 million US dollars )

- British diplomats: £ 100 million (around $ 200 million)

- World Council of Churches: $ 150 million

- Greek government agencies: $ 500 million.

As compensation for the riots, the Turkish government at that time paid a total of 60 million Turkish Lira (almost 21.5 million US dollars).

responsibility

The Menderes government blamed the pogrom of the political left around Aziz Nesin , Kemal Tahir and the socialists. The trials against Menderes and officials of his government and party, a total of 592 people, the Yassıada trials , initiated after the military coup in 1960 , established that his DP government and his continuing provocations were solely responsible . According to the Turkish penal code of the time , the death penalty was possible against persons "who seek to change, replace or repeal the constitution". Menderes was charged with “organizing anti-Greek riots in 1955”, “threatening the life of the former President İsmet İnönü ”, “organizing riots to destroy a newspaper” and corruption, and together with the governor of Izmir, Kemal Hadimil , Celâl Bayar , Fatin Rüştü Zorlu , Hasan Polatkan and ten other former government officials sentenced to death. In addition to Menderes, the ministers Zorlu and Polatkan were executed, the remaining death sentences commuted to life imprisonment . Celal Bayar was spared for reasons of age.

The Greeks tried to clarify responsibility through internationalization, but had little success in the eyes of the Greek historian Vryonis. The mass riots in Istanbul have not yet been researched by international organizations such as NATO or the UN ; the British NATO representative Cheetham described this as "undesirable". The US diplomat Edwin Martin described the allegations made to NATO as exaggerated. The governments of France, Belgium and Norway urged the Greeks to "let the past rest". The NATO Council issued a message that the Turkish government had done everything expected.

emigration

Almost all Turkish Greeks and Jews, as well as many Armenians, subsequently emigrated from Turkey, as for many of them the pogrom meant that they would never be recognized as Turkish citizens of equal status, but that they could be subject to attacks in the future. While almost 125,000 Orthodox Greeks lived as a minority in Istanbul in 1945, their number dropped dramatically from 1955. In 1999 there were still 2,500 Greeks living in Turkey. 1,650 of them lived in Istanbul in 2006. The Greek Orthodox Church emerged from the event strengthened in its international reputation.

Assessments

In the West, the Catholic Church dealt publicly and in detail with the pogrom as recently as 1955, while international politics remained silent almost entirely. In 1956, German academics began to deal with the “egregious excesses” in the context of current politics, including the historian Hans von Rimscha (1899–1987) and the political scientist Erik Boettcher. In the 1950s, the event was taken up in connection with other topics on various occasions, for example in 1959 by the sociologist Walter Sulzbach . The pogrom remained present in German-language scientific publications, but it did not reach the general public.

Several important works on the subject were published in 2005. In addition to a monograph by the Greek Byzantinist Speros Vryonis, Dilek Güven's Fahri-Çoker archive was made public in book form. Rear Admiral Fahri Çoker was a judge at the stand courts in Beyoğlu , which investigated the incidents following the events. Çoker, who died in 2001, bequeathed photos and documents from the proceedings to the Tarih Vakfı (“Foundation for History”) on condition that they be published after his death. The publication contains 246 photos and 175 documents on the events.

Orhan Pamuk , a Turkish author against whom the Istanbul public prosecutor had brought charges of “public degradation of Turkishness”, reported in his youthful memories of the blind destructive rage of his compatriots against all non-Muslims. For the writer and playwright Aziz Nesin , who died in 1995 , the perpetrators of that time were “people who became monsters”.

The pogrom is played down to this day in Turkey as "the September events". The responsible Turkish Prime Minister Menderes has a very high reputation in Turkey to this day. Streets have been named after him since the 1980s and a monumental mausoleum, the Anit Mezar, was built in Istanbul. In 1987 the international airport of Izmir was named after him and in 1992 the " Adnan Menderes University " was founded. In 2006/2007 his life was filmed for an extensive Turkish television series.

See also

literature

- Ülkü Agir: Pogrom in Istanbul, 6./7. September 1955. The role of the Turkish press in a collective looting and extermination hysteria. Klaus Schwarz, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-87997-439-9 .

- The anti-Greek riots of 6./7. September 1955 in Turkey. In: Pogrom. Journal for Threatened Peoples , No. 72/73, May 1980, p. 86 ff.

- Fahri Çoker: 6-7 Eylül Olayları. Fotoğraflar - Belgeler. Fahri Çoker Arşivi. Istanbul 2005, ISBN 975-333-197-5 .

- Dilek Güven: 6-7 Eylül Olayları. Istanbul 2005, ISBN 975-333-196-7 ( publisher information , German-language review ).

- Dilek Güven: Nationalism and Minorities. The riots against the Christians and Jews of Turkey in September 1955 (= Southeast European Work. Vol. 143). Oldenbourg, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-486-70714-4 .

- Dilek Güven: Riots against the Non-Muslims of Turkey: 6/7 September 1955 in the context of demographic engineering . In: European Journal of Turkish Studies (EJTS), Vol. 12 (2011), online since November 13, 2011, accessed on September 18, 2014.

- Helsinki Watch Report: Denying human rights and ethnic identity: The Greeks of Turkey. Washington 1992.

- Speros Vryonis: The Mechanism of Catastrophe: The Turkish Pogrom of September 6–7, 1955, and the Destruction of the Greek Community of Istanbul. New York 2005, ISBN 0-9747660-3-8 ( table of contents and reviews ).

- George Gilson: Destroying a minority: Turkey's attack on the Greeks . In: Athens News , June 24, 2005.

- Ilias K. Maglinis: Istanbul 1955: The anatomy of a pogrom ( Memento of February 9, 2008 in the Internet Archive ). In: Kathimerini , June 28, 2005.

- Robert Holland: Britain and the Revolt in Cyprus, 1954-59. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1998, pp. 75-78.

- Ali Tuna Kuyucu: Ethno-religious 'unmixing' of 'Turkey': 6–7 September riots as a case in Turkish nationalism. In: Nations and Nationalism , Vol. 11, No. 3 (2005), pp. 361-380.

- Karl Vick: In Turkey, a Clash of Nationalism and History . In: The Washington Post , September 30, 2005.

Web links

- 50 years ago a pogrom destroyed the old Constantinople. ( Memento from October 22, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) World Council of Churches in Austria (ÖRKÖ).

- Christiane Schlötzer: Pogrom against the Greeks in Istanbul. The Darkest Night on the Istiklal . Article on qantara.de from September 28, 2005 (accessed September 18, 2014).

- Thomas Seibert: A delicate anniversary for Ankara. Anti-Greek pogrom is being reworked . In: Der Tagesspiegel , September 7, 2005 (accessed September 18, 2014).

- Federal Agency for Civic Education (2014): The Istanbul Pogrom

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Michael Knüppel: The Turkish Orthodox Church . Pontus Verlag, Mönchengladbach 1996, ISBN 3980517802 , p. 106

- ^ A b c Munich University of Political Sciences (publisher): Political studies. Olzog Verlag, 1964, p. 560

- ↑ a b c d e f Wolfgang Freund (Ed.): Orient No. 1/1992. Deutsches Orient-Institut, Hamburg 1992, ISBN 3-89173-024-1 , p. 128

- ↑ a b c Greece. The Turks of Western Thrace. In: HRW.org , 1999, p. 8 (PDF; 350 kB) .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l 50 years ago a pogrom destroyed the old Constantinople. World Council of Churches in Austria (ÖRKÖ), September 5, 2005, archived from the original on October 22, 2007 ; Retrieved July 16, 2014 .

- ↑ A study by Dilek Güven on the private archive of the then highest military judge in a state of emergency, Rear Admiral Fahri Çoker, is based on central government planning of the events. The daily newspaper Radikal summarizes the study in a three-part series : Part 1 , Part 2 ( Memento of March 22, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) and Part 3 ( Memento of September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ a b c d e f Thomas Seibert: Tricky anniversary for Ankara. Anti-Greek pogrom is being reworked. In: Der Tagesspiegel from September 7, 2005 (article on the 50th anniversary)

- ^ Yeni Sabah September 8, 1955, Hürriyet September 8, 1955, Cumhuriyet September 8, 1955

- ↑ Helsinki Watch Report, 1990, p. 50

- ↑ a b c d Speros Vryonis: The Mechanism of Catastrophe: The Turkish Pogrom of September 6–7, 1955, and the Destruction of the Greek Community of Istanbul. Greekworks.com , New York 2005, ISBN 0-9747660-3-8 .

- ↑ Ahmet N. Yücekök: Türkiye'de Örgütlenmiş Dinin Sosyo-Ekonomik Tabanı. Ankara 1971, p. 93

- ↑ a b Klaus Detlev Grothusen, Winfried Steffani, Peter Alexander Zervakis: Cyprus. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1998, ISBN 3525362080 , p. 86.

- ↑ Wolfgang Freund (Ed.): Orient No. 1/1992. German Orient Institute, Hamburg 1992, ISBN 3-89173-024-1 , S. 127th

- ↑ Wolfgang Freund (Ed.): Orient No. 1/1992. Deutsches Orient-Institut, Hamburg 1992, ISBN 3-89173-024-1 , p. 125.

- ↑ a b Orhan Pamuk : "Istanbul". Memories of a city. Hanser, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-446-20826-7 .

- ↑ Cem Özdemir : The city of my mother. In: Der Tagesspiegel , November 30, 2003.

- ↑ a b c d e Herder correspondence. Monthly books for society and religion. Herder, Freiburg 1955, p. 125.

- ^ Steven Runciman, Peter de Mendelssohn (translation): Die Eroberung von Konstantinopel 1453. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3406025285 , p. 209.

- ↑ Turkish exchange rate 1923–1990 ( Memento from July 23, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The Verdict. ( Memento from January 5, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ) In: Time , September 22, 1961.

- ↑ George Gilson's review of the book by Speros Vryonis, ( June 17, 2008 memento in the Internet Archive ) Section Eyes shut on pogrom .

- ^ A b Günter Seufert, Christopher Kubaseck: Turkey - Politics, History, Culture. CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3406547508 , p. 162.

- ↑ Greece. The Turks of Western Thrace. In: HRW.org , 1999, p. 2, footnote (PDF; 350 kB) .

- ^ Hans von Rimscha, Erik Boettcher: The Soviet system in today's world , ISAR Fachbuch Verlag, Munich 1977, p. 1956.

- ^ Walter Sulzbach: Imperialism and national consciousness. European Publishing House, Hamburg 1959, p. 179.

- ^ Theodor Veiter: Nationality conflict and ethnic group law in the 20th century. Research Center for Nationality and Language Issues, Braumüller, Vienna 1977, p. 91.

- ↑ Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları: 6-7 Eylül Olayları. Fotoğraflar - Belgeler. Fahri Çoker Arşivi. Preface by Dilek Güven. Istanbul 2005, p. Ix.

- ^ Dilek Güven: Nationalism and minorities. The riots against Christians and Jews in Turkey in September 1955 . Oldenbourg, Munich 2012, pp. 148–153.