Ethnic groups in Turkey

The population groups in Turkey include Turks , Kurds , Zaza , Aramaeans , Lasen , Armenians , Greeks , Circassians , Albanians , Pomaks , Bosniaks , Georgians , Arabs , Chechens , Jews , Roma and numerous other ethnic groups, whose proportion of the total population is very low is.

The Republic of Turkey, proclaimed in 1923, and its predecessor, the Ottoman Empire , is a multi-ethnic state . In particular, the coastal areas, border areas and Eastern Anatolia were mostly inhabited by other ethnic groups. A significant Greek minority ( Phanariots ) lived in Istanbul well into the 20th century .

The numerically largest minority of the Kurds in Turkey is not recognized by the state as a minority, nor is the indigenous Aramean minority . There are also other ethnic groups. Peter Andrews listed 51 ethnic groups. Despite the ethnic diversity, Turks make up the majority with at least 70–80% . In Turkey, censuses have not been asked for the mother tongue since 1985; the results were no longer published after the 1965 census .

In the Ottoman Empire

In the Ottoman Empire , the Turks were the titular nation. However, due to the size of the empire (west-east expansion: from Morocco to Persia, north-south expansion: from Ukraine to Sudan), numerous different peoples lived in the country. The multiethnic state was strong and the country therefore formed an ethnic mosaic . Even the area of today's Turkey was populated by numerous ethnic groups. The largest Muslim groups included the Albanians and Bosnians in south-east Europe, Arabs in North Africa, and the Turks and Kurds in Anatolia and Thrace. The Jews included the Karaim / Krimchaks in the Crimea and the Sephardim / Ladinos in Asia Minor. The Serbo-Croatians , the Ukrainians , the Georgians , the Armenians in Eastern Anatolia, the Greeks in the Peloponnese and the Arameans in the Middle East, as well as various other Slavic and Caucasian peoples were among the Christians.

The minority legislation was correspondingly pronounced at the time: Recognized ethnic groups and minorities were organized and legally classified in millets according to their religious affiliation . This system gave these religious groups certain rights to manage their own affairs. Islamic law , Sharia , applied to questions and disputes that affected both Muslim and Christian subjects . Non-Muslim subjects were called dhimmi . The tax burden of the dhimmi was higher than that of the Muslims. There were also a number of discriminatory regulations and prohibitions, such as the prohibition of certain mounts. Non-Muslim minorities had better opportunities for social advancement than most Muslims through conversion within the framework of boy reading . However, the guarantee of minority protection depended on the politics of the respective rulers due to the absolutist system of the empire until 1876.

Turkish nationalism

Turkish nationalism already existed in the Ottoman Empire in the second half of the 19th century. The Turkish nationalists included the Young Ottomans / Young Turks , who stood primarily for constitutionalism , but were also responsible for crimes against religious minorities. The Committee for Unity and Progress was also nationalist and opposed to ethnic-religious diversity. The then freedom fighter for the Turks and later state founder Mustafa Kemal Ataturk rejected both movements and wanted a modern Turkish nation state . He recognized the equality of all citizens regardless of religion or gender.

With the transition to Turkey, Turkish nationalism in the form of Kemalism formed an important basis for the new state. In 1924 the new constitution was passed, granting all citizens equal rights. A Turk was someone who professed to be a Turkish citizen regardless of ethnic or religious affiliation . Members of ethnic minorities, from 1928 also religious minorities, were able to rise to the highest state offices, provided they had professed Turkish citizenship and thus citizenship.

At the same time, plans were drawn up based on racist criteria: Armenians were banned from staying east of the Samsun - Silifke line , Arabs had to leave the border region with Syria, and Georgian Turks were to be excluded from the provinces of Rize, Kars and Ardahan. Greeks were only tolerated in Istanbul. Finally, the expulsion of the non-Turkish elements from the border area with Syria was implemented.

Extreme manifestations of Turkish nationalism found expression in the Turkish thesis of history ( Türk Tarih Tezi ) and in the so-called solar language theory . The early advanced civilizations of Anatolia were viewed as the result of early Turkish immigration and attempts were made to prove that Turkish was the original language from which all other languages derived.

This policy also began with the Turkishization of geography . Place names and field names that were not Turkish, not Muslim, disparaging or incomprehensible were changed, initially sporadically. But in 1956 a separate commission was established in the Ministry of the Interior . Harun Tunçel states in a study that by 1968 12,000 of 40,000 villages had been renamed. Furthermore, in 1977 a list of 2000 changed field names was published. The main goal was to erase the non-Turkish or non-Muslim character of the places by deleting additions to names such as church or ethnonyms.

Situation in the Republic of Turkey

There are 47 schools in the minority communities in Turkey, 22 of which belong to the Armenian, 22 to the Greek and 3 to the Jewish community. The classes for chemistry, physics and mathematics take place in the respective minority language, all other subjects are taught in Turkish.

The Ministry of Education, which is subordinate to Minister Hüseyin Çelik , received negative attention from the EU Commission in April 2003 . The minorities are exposed to certain discriminatory practices on the part of the authorities. It was complained that the content of the state-published history textbooks incited hostility against minority groups. In addition, the ministry obliged Turkish teachers to take part in further training measures of a Turkish nationalist nature and initiated new editions - actually - of outdated Turkish textbooks in which non-Muslims in Turkey are referred to as "spies", "traitors" and "barbarians". There is also no lack of information that their schools, churches and synagogues are “harmful communities”. Although Turkey has now been reprimanded by the EU for these orders, the controversial nationalist education minister Hüseyin Çelik remained in office.

Legal situation

Since the reform in 2005, the Criminal Code (tStGB) and the Code of Criminal Procedure with regard to minority policy have been in line with the rule of law. However, the legal practice and some controversial articles remain the subject of criticism:

- The Art. 301 TPC , the "State of insulting the Turkish nation, the Turkish Republic and the institutions and bodies", the criminal offense.

- Art. 81 lit. c) of the Political Parties Act, which requires parties to use only the Turkish language in writings and publications of their statutes and programs, at their party conventions, at meetings in public or in closed rooms, at their demonstration meetings and in their advertising .

- Art. 215 tStGB, which makes praising criminal acts and offenders ( suçu ve suçluları övme ) a punishable offense. Courts can impose prison sentences if, for example, people use the salutation “Dear Mr.” Öcalan ( Sayın Öcalan ).

- The electoral threshold of 10 percent prevents parties from entering parliament that fail to pass this electoral hurdle nationwide.

- Christian communities are not recognized as legal entities and must therefore always have a private person as the owner of real estate. In such ways, the Christian minorities are constantly threatened with the loss of their facilities (in addition to the places of prayer and schools).

- The anti-terror law, which allows the state to temporarily ban newspapers.

Turks

The Turks are the people who support the state and form the titular nation with a share of 70 to 80% of the total population . They speak Turkish , a Turkic language . Turkish is also the only official language. The majority of the Turks are Sunni Muslims , there are also Turkish Alevis . Only very small minorities are Christians or Jews.

Originally the Turks immigrated from Central Asia as Oghusen and, after battles with the local Byzantines, formed the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum as part of the great empire of the Seljuk princely family with Konya as the capital. They also formed the titular nation in the multi-ethnic state of the Ottoman Empire (which was also known as the Turkish Empire ). In Turkey, the Turks have been and are deliberately given preferential treatment by the state for a long time. So the Turks officially form the Turkish nation.

Numerous people from Turkish and assimilated families of other Muslim ethnic groups immigrated to Anatolia as displaced persons and survivors of massacres ( muhajir / refugees) , mainly after the Ottoman loss of Romanian and other areas . In the years 1855 to 66 alone, as a result of the Crimean War, there were one million. As a result of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 , 80,000–90,000 Turks and Tatars fled to Turkey and Bulgaria, and many Circassians who were resettled to Anatolia . Assimilated Muslim families who speak the Turkish language often also refer to themselves as Turks , although ethnically they belong to a different group. These include the Balkans ( Albanians , Bosniaks and the Gagauz , who speak a dialect of Turkish) and Caucasus peoples (Circassians, Meshes and Lases ) who immigrated in the 19th and 20th centuries . There were also people of Turkish origin who had migrated to Anatolia during the expansion of the Ottoman Empire from Anatolia to the Balkans or the Caucasus, including Balkan Turks and Adjara Turks .

Recognized minorities

According to the provisions of the Lausanne Treaty, which is still valid today , the following groups have minority status and therefore enjoy all minority rights:

- Armenians

- Greeks

- Jews (see Turkish Jews )

Armenians

About 60,000 Turks of Armenian origin live in Turkey. In Istanbul alone there are 45,000 Armenians. Under Turkish law, you have the same rights as all Turks, but in practice, like the Christian minority, they are often discriminated against and disadvantaged. Discrimination against minorities is an issue in Turkey's accession negotiations with the European Union .

The Armenian churches are also not legal entities and can therefore not carry out any legal transactions, such as buying real estate or other property. The churches are not allowed to train their staff themselves, and their property is repeatedly expropriated without compensation. Most of the around 2200 monasteries and churches registered in 1912/13 as well as Armenian schools have been destroyed or misused since 1915 - in some cases even after the founding of the Republic of Turkey (e.g. the demolition of St. Stepanos Church and the connected elementary school of St. Nerses 1971 in Istanbul, the Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator in Kayseri as a sports hall, the Monastery of Chtsgonk as an artillery target of the Turkish military, the Church of Our Lady in Talas as a mosque, the Varak Monastery near Van as part a farm, the Kaymaklı Monastery near Trabzon as a stable, the St. Garabed Monastery and the Holy Apostle Monastery of Mus as pasture and stables, the St. Illuminator Church in Mudurga near Erzurum as a prison).

The Armenian congregations currently have only 55 churches ( apostolic , catholic and evangelical ). There is a preschool, 17 elementary schools and 5 high schools. A total of 2,906 students are taught by 488 teachers at these schools (as of 2008). There are 52 Armenian foundations and 3 newspapers and a magazine. There are also two Armenian hospitals.

The murder of Christian priests and missionaries, which has increased in recent years, has not been committed by the state, but by fanatical citizens. They are by no means covered by the law. Various human rights organizations confirm this situation.

Greeks

The Anatolian Greeks are called rum in Turkish , whereas the Greeks are called Yunan . The Greeks in Eastern Thrace, Istanbul and Izmir are to be distinguished from the Pontic Greeks in the north and northeast of Turkey (Pontos Mountains). Almost a century ago, millions of Greeks lived in the coastal areas of Asia Minor. In 1914, about 1.73 million Greek-speaking people still lived in Turkey . The Greek minority played an important role in the economic and social life of the Ottoman Empire. During the First World War, however, the Greeks were persecuted . After the defeat of the Greek army in the Greco-Turkish War in 1922, the population exchange between Greece and Turkey - as provided for in the Lausanne Treaty - was decided and carried out. All but 120,000 Greeks were expelled.

The actual history of the Greeks in Asia Minor ended after around 4,000 years. Since the Greek colonization , beginning in the 11th century BC, Greece had always been the country around the Aegean Sea, with outstanding personalities from the cities of Asia Minor, today's Turkey, such as Homer and most pre-Socratic philosophers, e . B. Thales of Miletus, like the atomists who anticipated modern atomic theory, and many others. One of the most important shrines in Greece was the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus , which was counted among the Seven Wonders of the World .

As early as the 1930s, especially since 1932, Greeks have been increasingly discriminated against in Turkey. So they were only tolerated in Istanbul. Laws were passed to force the Greek minority to emigrate. The introduction of the Varlık Vergisi wealth tax in 1942, which was much higher for non-Muslims than for Muslims, drove many Greeks to financial ruin.

Around 55,000 Greeks lived in Istanbul until 1955, but most of them had to leave after a series of riots in September 1955 .

No more than 3,000 to 4,000 Greeks live in Turkey today, most of them in Istanbul and on the Aegean island of Gökçeada . Today they maintain 15 elementary schools and 6 high schools. There are a total of 217 students and 103 teachers. Two Greek-language newspapers appear. The Greeks own 75 foundations, 90 houses of prayer and a hospital.

Jews

Parallel to the secularization of the Turkish state after 1923, the Jewish community also experienced a change from a religious community to Turkish Jews , then to Jewish Turks and finally to Turks of the Mosaic faith . Most of the Turkish Jews ( Yahudi or Musevi ) are descendants of the 300,000 Sephardic Jews who had to leave the Iberian Peninsula after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492 or Portugal (1497) or who fled Nazi rule. The Spanish Jews originally speak the Ibero-Romanic Ladino , to which Turkish elements have been added over time. French dominates as the educational language. The Ashkenazi Jews come from Russia . In 1920 the Jewish community had around 100,000 members. Due to the persecution of Jews by the National Socialists , many Jews, especially scientists and academics, found refuge in Turkey in the 1930s . From 1941 onwards he emigrated to Palestine, which reached its peak after the establishment of the State of Israel . In 1949 alone, 20,000 Jews emigrated. The 1965 census counted a total of 38,000 Jews. Today around 17,000-18,000 Jews live in Turkey (as of 2016); before 2010 it was 26,000. The Jewish community maintains 36 synagogues, a preschool, a primary school, a grammar school and two hospitals. The weekly newspaper Şalom also appears there . The head of the Turkish Jews has been called Hahambaşı since around 1835 . Towards the end of the 17th century, a few years after the death of Shabbtai Zvi , a group of Jews converted to Islam called Dönme formed in Thessaloniki . There is also a Karaim community in Istanbul to this day . A study by the Center for Turkish Studies reports de facto entry restrictions for Jews in senior civil servants or high military positions.

Not recognized as a minority

Due to the fact that the Turks first immigrated to Asia Minor in the High Middle Ages, as well as the later nationality policy, there is an ethno-religious mosaic in Turkey. Most of the peoples living in Turkey are not recognized as a separate ethnic group. The main groups are:

- Iranians

- Members of various Turkic peoples

- Slavs

-

Caucasian

- Northwest Caucasians : Circassians (with Abazines , Adygejes, Kabardines and Abkhazians ), Chechens (with Ingush )

- South Caucasians : Georgians and Lases

- Semites

- Albanians

- Hemşinli

- Roma and Cathedral

Kurds

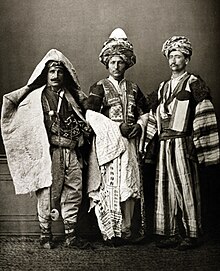

The photograph was taken by the Ottoman court photographer Pascal Sébah in 1873 and shown at the world exhibition in Vienna that same year .

history

The year 1514 was one of the decisive events in Turkish-Kurdish relations. When the Sunni Sultan Selim I went into the battle of Chaldiran against the Shiite Shah Ismail I, the Kurds (also Sunni) allied themselves with the Ottomans. As a result, they accepted Ottoman suzerainty over their territories in return for fixed privileges.

After a first failed attempt in 1876, Turkish parliamentarism began with the Young Turkish Revolution of 1908. Even after the founding of the republic in 1923, Kurdish notables (tribal leaders) were allowed to represent their interests in Ankara on the condition that they did not fight the indivisibility of the nation .

Even before the founding of the republic, there were uprisings by the Kurmanish and Zaza, driven by national and religious motives:

- 1920: the Koçgiri uprising

- 1925: the Sheikh Said uprising

- 1926: the Ararat uprising

- 1937: the Dersim uprising

- 1984: the PKK's armed struggle and war

Turkey often reacted with military harshness. In addition, the state took the following measures:

- The existence of a Kurdish people was denied by the state for decades.

- Numerous place names (most of them Kurmanji and Zazaki) were Turkish.

- Kurmanschen and Zaza were given Turkish surnames.

- The use of Kurmanji and Zazaki in public was prohibited by law in 1983. The ban was lifted in 1991.

- With the so-called “Tunceli Law”, regions in Western Anatolia were designated for the settlement (literally “assimilation”) of the Kurdish population. Other regions should be evacuated entirely. Further zones have been cleared for the resettlement of settlers of Turkish origin. Traditions were banned and tribal rights abolished. (cf. Franz)

- Kurdish parties have been banned several times (HEP, HADEP , DEHAP, DEP, DTP ), Kurdish politicians have been imprisoned and dozen of them have been murdered.

- During his liberalization phase, Prime Minister Erdoğan approached the Kurds. The ban on the Kurdish language was lifted, the teaching of the Kurdish language was included as an optional subject in the curriculum, state investment in the inhabited predominantly by Kurds areas massively increased, and the first time a peace process with the PKK started, but after two years failed .

Kurdish representatives were openly represented in parliament after 1991, when the SHP added some HEP members to their lists as independent candidates. The Kurdish party HEP failed at the ten percent hurdle. By working with the SHP, 14 HEP politicians made it into parliament as independents. Some time later, the SHP ended its collaboration with the HEP. The reason for this were various nationalist statements by the Kurdish parliamentarians and, above all, those that the SHP did not consider to be sufficiently distant from the PKK .

Political situation

By taking action against Kurdish politicians as part of the struggle against the separatist PKK, Turkey has deprived itself of possible contacts for solving the Kurdish question on several occasions. Kurdish parties are still not allowed to write statements in Kurdish. The use of Kurdish is still subject to restrictions in practice, despite the lifting of the language ban. These restrictions include fines for using forbidden Kurdish letters (W, Q and X), police seizure of Nouruz invitations containing the letter “W”, investigations into Kurdish-language pages on the Diyarbakir website and measures against Kurdish political parties who use the Kurdish language in their pronouncements. Kurdish park, street and place names are often banned by the responsible provincial administration ( Valilik ) or district administration ( Kaymakamlık ) on the grounds that they encourage separatism. In September 2000, the Turkish Administrative Court ( Danıştay ) unanimously banned such place and street names because they were separatist, incendiary or Kurdish. The reuse of former non-Turkish place names is also prohibited according to Art. 2 of the Provincial Administrative Law. There are no native-speaking Kurdish lessons in state schools and according to Art. 42, Paragraph 9 of the constitution, it is prohibited.

As Human Rights Watch reported on December 20, 2006, the government has inadequately fulfilled its self-imposed legal obligation from 2004 to the present to compensate hundreds of thousands of people, mostly Kurdish villagers, for the Turkish military measures against insurgents in the 1980s and 1990s. At that time, the villagers in the southeast of the country had been displaced. Human Rights Watch reported that reparations payments were arbitrary, unfair, or withheld from refugees.

In April 2013, the Turkish President Abdullah Gül admitted “serious mistakes by the state” in dealing with the Kurdish minority.

Religions

The vast majority of Kurds are Sunni Muslims. There are also Alevi communities among the Kurds. A religious minority among the Kurds are the Yazidis , a syncretistic religious community with elements from all oriental religions such as Mithraism , Zoroastrianism , Manichaeism , Judaism and Christianity . Ethnically, the Yazidis can be assigned to the Kurds. They still live in a few villages in Southeast Anatolia. Due to their religious affiliation, the Yazidis have been subjected to persecution by their Muslim neighbors in many cases. In today's Turkey, because of their ethnic and religious affiliation, they occupy a double position of outsider and have to endure discrimination. Often they are incorrectly referred to as "devil worshipers" (Şeytana tapan) . There is no longer any state-directed persecution, but most of the Yazidis have emigrated to Europe in recent decades.

Assyrian (Suryanil)

The Assyrians are a Christian minority in Turkey. Their number has fallen sharply in the last decades of the 20th century due to displacement and emigration. Their traditional settlement areas are the provinces of Mardin ( Tur Abdin ), Siirt and Hakkari. According to their denomination, they are divided into "West Syrians" and "East Syrians" ( Chaldeans and Assyrians ). There are no longer any East Syrian Christians in Turkey.

Western Syrians

The majority of the Western Syrians belong to the Syrian Orthodox Church . Their traditional settlement area is the Tur Abdin. The Zeitschrift für Türkeistudien (1/95) estimates their number in Turkey at 20,000 people, half of whom live in Istanbul due to internal migration. Their language is called Turoyo and belongs to the New Aramaic branch of Semitic. In 1997, the governor of the province of Mardin issued a ban on the monasteries Zafaran and Mor Gabriel from accommodating foreign guests and from teaching religion and mother tongue. International protests meant that at least the ban on accommodation was lifted. Language lessons in Aramaic are still prohibited.

Eastern Syrians

The majority of the East Syrians profess a church of the East Syrian rite, namely the Chaldean Catholic Church united with Rome or the independent Assyrian Church of the East of the so-called "Nestorians". The Center for Turkish Studies estimates their number at around 2000 people. They have largely left their villages in southeast Turkey and now live in Istanbul and Europe. Their language is one of the neo-Aramaic dialects.

Circassian

The Circassian people who immigrated from the Caucasus form a larger ethnic group within Turkey. Circassians live scattered across Turkey and mainly in villages. They are almost exclusively Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi orientation. Like the Ossetians and Chechens, the Circassians came to the Ottoman Empire as refugees from the North Caucasus after the Caucasus War 1817–1864 and the Russo-Turkish War 1877–1878 . Between the years 1855 and 1880, a total of around 600,000 Circassian refugees arrived in the Ottoman Empire. Today about 2 million Circassians live in Turkey. The closely related ethnic groups of the Abasins and the Abkhazians are also counted among the Circassians in Turkey . The vast majority of Circassians in Turkey have been assimilated, many now speak Turkish as their mother tongue and just under half still speak one of the Circassian languages , predominantly Kabardian (550,000 speakers) and, secondly, Adygean (275,000 speakers).

Ossetians

The Ossetians With about 100,000 people one of the smaller ethnic minorities in Turkey. They live mainly in large cities and scattered all over Turkey in their villages . The Iranian- speaking Ossetians are an immigrant Caucasus people, the vast majority speak Ossetian as their mother tongue. In contrast to the Christian Ossetians in Georgia and Russia, the Ossetians in Turkey are almost exclusively Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi direction.

Chechens

The Chechens With about 70,000 people one of the smaller ethnic minorities in Turkey. They live mainly in large cities and scattered all over Turkey in their villages . In Turkey, the Chechens also include the closely related Ingush ethnic group . Among the Chechens, there are 1,000 people, the largest contingent of civil war refugees from the Caucasus. The Chechens are an immigrant Caucasus people, the vast majority speak Chechen and Ingush as their mother tongue. The Chechens in Turkey are almost exclusively Sunni Muslims of the Shafiite direction.

Arabs

The Arabs form a larger ethnic group within Turkey. Their original settlement areas are the south and southeast of Anatolia in the provinces of Adana , Batman , Bitlis , Gaziantep , Hatay , Mardin , Mersin , Muş , Siirt , Şanlıurfa and Şırnak . Before the Syrian civil war, around 800,000 Arabs lived in Turkey. The Muslim Arabs form the largest group within this ethnic group. There are also 300,000 to 350,000 Nusairians and 18,000 Christians . Magazines or books in the Arabic language and script do not exist in Turkey. Arabic was permitted as the school language until 1929. On April 4, 2010, TRT at-Turkiyya , Turkey's first state television broadcaster in Arabic and, after TRT 6, Turkey's second state television broadcaster for minorities, went on air. Today, Arabic is taught as a cult language of Islam in technical schools for imams and preachers and in theological faculties.

In addition to the long-established people of Arab ethnicity, the war in Syria from 2011 brought several million refugees, preferably of Arab ethnicity, to Turkey, whose whereabouts are unclear and whose integration into the Turkish population is in question.

Assaults

Against Armenians

On January 19, 2007, the journalist Hrant Dink , known as the most prominent mouthpiece of the Armenians, was shot dead. Police officers triumphantly had themselves photographed and filmed with the journalist's killer and a Turkish flag, which sparked global protests. The perpetrator boasted that he had killed an unbeliever who offended Turkey.

Against Greeks

On the night of September 6th to 7th, 1955, a pogrom took place in Istanbul, but also in other parts of Turkey , primarily against the Greek minority. In the course of the crimes, however, Armenians and Jews were also victims. Murder, rape and gross mistreatment went hand in hand with destruction. The fanatical Muslim population set fire to around 72 Orthodox churches and more than 30 Christian schools in Istanbul alone. It also desecrated Christian cemeteries and the bones of the clergy, devastated around 3500 houses, 110 hotels, 27 pharmacies and 21 factories and an estimated 3500 to 4000 shops. The pogrom almost completely wiped out Greek-Christian life in Turkey, as around 100,000 Greeks left their old homeland as a result. From 110,000 Greeks in 1923, their number in Turkey has fallen to 2,500 today.

Against Kurds

On November 10, 2005, a hand grenade exploded in a bookstore run by Kurds in the middle of the afternoon in the district town of Şemdinli in the province of Hakkâri . A person was killed in the explosion and the shopkeeper was able to avoid the attack. People on the street caught the suspected bomber when he tried to get into a car with two other people in it.

On November 22, 2004, the Kurd Ahmed Kaymaz and his 12-year-old son Uğur were shot by Turkish police in front of their house in Mardin- Kızıltepe . On April 18, 2007, the four police officers responsible were acquitted.

On April 27, 2008, the pro-Kurdish party DTP organized an evening event in Sakarya Province . A group of around 100 Turkish nationalists tried to storm the hall. The celebrants were trapped in the hall for more than 5 hours, which is why 11 people developed circulatory problems. A man suffered a heart attack and died shortly after in hospital.

Against other minorities

In June and July 1934 a pogrom against Jews broke out in East Thrace , the aim of which was the complete Turkishization of European Turkey.

On July 2, 1993, an angry crowd gathered after Friday prayers in front of the Madimak Hotel in Sivas, where Alevi musicians, writers, poets and publishers were staying. Among them was the controversial writer Aziz Nesin , who had translated the heretical novel “ The Satanic Verses ” into Turkish. In the midst of the angry protesting crowd, incendiary devices were finally thrown at the hotel. The fire spread rapidly, with 35 people (including 34 Alevis) being burned alive; the author Aziz Nesin, who is said to have been the target of the attack, survived with minor injuries. Although the police and fire brigade were alerted early on, they did not intervene for eight hours. Witness statements and video recordings show how a few police officers helped the crowd and an advancing military unit withdrew. The Alevis call this attack the "Sivas massacre", although from their point of view the arson attack was aimed at them, and have since felt abandoned by the state.

See also

literature

- Hüseyin Aguicenoglu: Genesis of Turkish and Kurdish nationalisms in comparison , Münster: LIT 1997, Heidelberg Studies on International Politics; 5, ISBN 3-8258-3335-6

- Peter Alford Andrews (Ed.): Ethnic Groups in the Republic of Turkey . Wiesbaden 1989

- Wilhelm Baum: Turkey and its Christian minorities: history - genocide - present , Kitab Verlag, Klagenfurt-Wien 2005, ISBN 3-902005-56-4

- Karl Binswanger: Studies on the status of non-Muslims in the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century. Diss. Phil. Munich 1977, ISBN 3-87828-108-0

- Erhard Franz : Population Policy in Turkey. Family Planning and Migration between 1960 and 1992. Hamburg: Deutsches Orient-Institut 1994

- Klaus-Peter Hartmann: Investigation of the social geography of Christian minorities in the Middle East , Wiesbaden 1980

- Krisztina Kehl-Bodrogi: The Kızılbaş / Alevis. Research on an esoteric religious community in Anatolia. Islamic Studies 126. Berlin

- Hans Krech: The civil war in Turkey 1978-1999. Köster, Berlin 1999. ISBN 3-89574-360-7

- Kai Merten: The Syrian Orthodox Christians in Turkey and Germany , Hamburg 1987

- Jürgen Nowak: Europe's trouble spots. Nationality conflicts from the Atlantic to the Urals. Hamburg 1994

- Vartkes Yeghiayan: British Reports on Ethnic Cleansing in Anatolia, 1919-1922: The Armenian-Greek Section . Center for Armenian Remembrance, Glendale CA, 2007, ISBN 978-0-9777153-2-9

- Center for Turkish Studies (ed.): The ethnic and religious mosaic of Turkey and its reflections on Germany. Munster 1998

Web links

- Law On Foundations No 5737 ( the new law on associations ) (PDF; 99 kB; English)

- New report from the Turkish Foreign Ministry on the minorities of the Greeks, Armenians and Jews. In the Turkish Milliyet , December 12, 2008 (Turkish)

- Greek Orthodox Minority in Turkey (PDF; 130 kB; English)

- Human Rights Report of the US on Turkey for 2008 (English)

- Society for Threatened Peoples , Tessa Hofmann : Christian Minorities in Turkey

Individual evidence

- ↑ http://lerncafe.de/joomla/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=493&Itemid=689

- ↑ a b Klaus Kreiser, Christoph K. Neumann: Small history of Turkey. Stuttgart 2009, p. 473. (the value refers to Turks of Sunni faith, excluding Alevis )

- ↑ Guus Extra, Durk Gorter: The other languages of Europe . Demographic, Sociolinguistic and Educational Perspectives. Multilingual Matters, 2001, ISBN 1-85359-509-8 , pp. 39 ( Google Books [accessed April 2, 2010]).

- ↑ See also the dissertation by Karl Binswanger: Investigations on the status of non-Muslims in the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century. With a redefinition of the term Dhimma . Munich 1977

- ↑ a b Turkish Constitution of 1924 : Constitutional text ( Memento from November 1, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Vahé Tachjian: Etat-nation et minorités en Turquie kémaliste. in: Revue d'histoire de la Shoah, Center de documentation juive contemporaine, Paris 2003

- ↑ Online edition of the article Renamed Villages in Turkey by Harun Tunçel

- ↑ AZINLIK OKULLARINA. In: http://www.cnnturk.com/ . CNN Türk, June 19, 2009, accessed June 19, 2009 (Turkish).

- ↑ Regular report on Turkey's progress on the way to accession , 2003 p. 43 ( Memento of April 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF file; 602 kB)

- ↑ Hans-Lukas Kieser: ORIENT . Issue 1, 2003, p. 66

- ↑ Hürriyet , May 12, 2003

- ↑ Law No. 2820 of April 22, 1983 on political parties, RG No. 18027 of April 24, 1983; German translation by Ernst E. Hirsch in: Yearbook of Public Law of the Present (New Series). Vol. 13, Mohr Siebeck Verlag, Tübingen 1983, p. 595 ff.

- ^ Society for Threatened Peoples

- ↑ Anti-Terror Law No. 3713 of April 12, 1991, RG No. 20843 of April 12, 1991.

- ^ Michael Neumann-Adrian / Christoph K. Neumann: Turkey. A country and 9,000 years of history , Munich, 1990

- ↑ Review - Already after 1840, many Muslims had fled Europe after massacres. In the years 1855-66 there were one million in the wake of the Crimean War. Hundreds of thousands fled Serbia and Crete and thousands more after the Russo-Ottoman War. And now there was the massacre of Muslims in the remaining Balkan regions.

- ^ Article Turks in Encyclopaedia of Islam , Section The Turks outside Turkey from the late 19th century to the present

- ↑ Armenian cultural monuments in the neighboring countries of Armenia . ( Memento of July 30, 2004 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 363 kB) In: ADK 117 , vol. 2002, issue 3, pp. 38–40

- ^ Municipal council of the Church of St. Stepano in Haledjoglu in: Pogrom. Journal for Threatened Peoples , No. 85, Volume 12, Oct./Nov. 1981, p. 32

- ↑ arms Kurkdjian: The Türkifizierungspolitik Turkey . ( Memento of July 11, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 9.78 MB), page 13 (Armenian)

- ↑ Dickran Kouymjian: The destruction of Armenian cultural monuments - a continuation of the Turkish genocide policy . Page 156 in: Pogrom, series threatened peoples (ed.): The crime of silence. The trial of the Turkish genocide against the Armenians before the Permanent Tribunal of the Peoples . Fuldaer Verlagsanstalt, 2000 (Original title: Le crime de Silence. Le Génocide des Arméniens.)

- ↑ Astrig Tchamkerten: The Gulbenkians in Jerusalem . Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon 2006 p. 41

- ↑ a b Jean V. Guréghian: Les monuments de la région Mouch Sassoun - historique Van en Arménie . Sigest, 2008 ISBN 2-917329-06-8

- ↑ Photo series of the condition of the monastery in 2007 at derStandard.at, accessed on June 11, 2009

- ↑ Amalia van Gent: Borderline Trabzon. The trading city is the epitome of what Turkey should not enter the EU. It is considered a breeding ground for radical Islamists. A classic case of character assassination. In: NZZ Folio . June 2009, p. 52

- ↑ Pars Tuğlacı : Tarih boyunca Bati Ermenileri. Cilt III. (1891–1922) , Pars Yayin ve Tic., Istanbul and Ankara, 2004 ISBN 975-7423-06-8

- ↑ aidrupal.aspdienste.de ( Memento from November 1, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ gfbv.de ( Memento from November 5, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Execution in the name of the prophet . In: The world

- ↑ a b Shaw: The Ottoman Empire Census System and Population, 1831-1914

- ↑ Varlik Vergisi ( Memento from January 26, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Pogrom of Istanbul

- ↑ a b Rifat N. Bali : Les Relations entre Turcs et Juifs dans La Turquie Moderne, Istanbul: Isis, 2001

- ↑ a b Turkey Virtual Jewish History Tour | Jewish Virtual Library . jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- ↑ Why Jews in Terror-Stricken Turkey Aren't Fleeing to Israel Yet . hairetz.com. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- ↑ musevicemaati.com Official website of the Turkish Jews Turkish Jews Today: The present size of Jewish Community is estimated at around 26,000. ( Memento from October 20, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (Turkish, English)

- ^ Martin Sicker: The Islamic world in ascendancy: from the Arab conquests to the siege of Vienna. Greenwood Publishing Group, Westport, Conn. 2000, ISBN 0-275-96892-8 , p. 197.

- ^ A b Klaus Kreiser, Christoph K. Neumann A Little History of Turkey , Stuttgart 2009, p. 476f.

- ↑ See Act No. 2932 of October 19, 1983 on publications in languages other than Turkish, RG No. 18199 of October 22, 1983.

- ↑ With Art. 23 lit. e) of the Anti-Terror Law No. 3713 of April 12, 1991, RG No. 20843 of April 12, 1991.

- ↑ Law No. 2884 of December 25, 1935 on the administration of the Tunceli Vilâyets, RG No. 3195 of January 2, 1936.

- ↑ http://www.haber7.com/guncel/haber/1130318-kurtcenin-onundeki-engeller-bir-bir-kaldiriliyor

- ↑ http://www.haberturk.com/polemik/haber/749821-kurtce-secmeli-ders-mi

- ↑ http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/dogu-ve-guneydogu-da-yatirima-sifir-vergi-ve-faizin-yarisi-devletten-geliyor-19747131

- ↑ http://www.ensonhaber.com/dogu-ve-guneydoguya-35-milyar-liralik-yardim-paketi-2016-07-04.html

- ^ Sabah , October 25, 2005 . 100 million lira fines for using the letter "W".

- ^ Hürriyet , March 9, 2007

- ↑ Hürriyet , January 12, 2007

- ↑ Radikal , February 15, 2007 ( Memento of September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ). Sanctions against the HAK-PAR for using Kurdish.

- ↑ Sabah , March 2, 2007

- ^ Milliyet , February 26, 2007

- ^ Hürriyet , December 2, 2005

- ↑ Radikal , January 22, 2001

- ↑ Provincial Administrative Law No. 5442 of June 10, 1949, RG No. 7236 of June 18, 1949

- ^ Human Rights Watch , December 14, 2006

- ↑ Abdullah Gül admits Turkish mistakes in Kurdish policy. welt.de, April 3, 2013

- ↑ Svante Lundgren: The Assyrians: From Nineveh to Gütersloh . Lit Verlag, Münster 2016, ISBN 978-3-643-13256-7 .

- ↑ International Society for Human Rights

- ↑ Center for Turkey Studies (ed.): The ethnic and religious mosaic of Turkey and its reflections on Germany , Münster 1998, p. 128

- ↑ WED Allen, Paul Muratoff: Caucasian Battlefields - A History of the Wars on the Turco-Caucasian Border 1828-1921 . Battery Press, Nashville 1966; P. 104. ISBN 0-89839-296-9 (English)

- ↑ UNPO : Cherkessia (English)

- ↑ Ülkü Bilgin: Azınlık hakları ve Türkiye . Kitap Yayınevi, Istanbul 2007; P. 85. ISBN 975-6051-80-9 (Turkish)

- ^ Ali Tayyar Önder: Türkiye'nin etnik yapısı: Halkımızın kökenleri ve gerçekler . Kripto Kitaplar, Istanbul 2008; P. 103. ISBN 605412503-6 (Turkish)

- ↑ The Nusairians worldwide and in Turkey (Turkish) ( Memento from October 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Christians in the Islamic World - From Politics and Contemporary History (APuZ 26/2008)

- ↑ TRT-Arabic goes on air: The new station "TRT-Arabic" goes on air today.

- ^ Luke Coffey: Turkey's demographic challenge. Retrieved August 23, 2018 .

- ^ The Impact of Syrian Refugees on Turkey. Retrieved August 23, 2018 .

- ^ Daily Telegraph , Jan. 21, 2007

- ↑ Concern in Europe and Central Asia, January – June 2007, TURKEY ( RTF ; 51 kB) at Amnesty-tuerkei.de (accessed April 23, 2008)

- ↑ 'DTP'nin düzenlediği gecede gerginlik' on cnnturk.com (accessed April 27, 2008)