Jewish Spanish

| Jewish Spanish | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

|

|

| speaker | 25,000 - 100,000 at most | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -2 | ( B ) lad | ( T ) lad |

| ISO 639-3 |

lad |

|

Jews Spanish , Judeo-Spanish , Djudeo-Espanyol (in Hebrew Scripture גֿודֿיאו-איספאנייול), also Ladino , Djudezmo and, in northern Morocco, Hakitía are names for a Romance language developed by the Sephardic Jews since the Middle Ages , which is sometimes called Sephardic (from Hebrew s (ĕ) farad: Iberia) after them . It has evolved over the centuries from different varieties of the Ibero- Romanic languages, especially Castilian, and under the influence of several contact languages . As a Jewish language, Jewish Spanish has many influences from Hebrew and Aramaic , but also from Arabic , Turkish , Italian , Greek and Slavic languages , depending on the area in which the Sephardi settled after their expulsion from the Iberian Peninsula. Borrowings from French , which was learned as an educational language in many Mediterranean countries , are also common. The relationship between Jewish Spanish and the Sephardi is comparable to that between Yiddish and the Ashkenazim in terms of cultural history and sociolinguistics .

The different language names

The designation of the language to be dealt with here is not uniform. Which of the well-known names is used is partly due to geographical reasons. Some researchers see the lack of a stylistically neutral name as an indication that the language is not held in high esteem and that "its speakers qualify it as jargon, as it were."

Jewish Spanish

( Djudeo-Espanyol , Spanish: Judeo-Español .) For many language historians, Judean Spanish is the appropriate term to denote the Sephardic language, as it refers to Spanish as its basis on the one hand and names the speakers of the language on the other.

Ladino

Ladino is often used, especially in Israel, to denote the language of the Sephardic Jews, but in a narrower sense only describes the process of interlinear translation from the Hebrew Bible and the Hebrew prayer book ( Seder and Siddur ) into that of the Jews of the Iberian Peninsula spoken Romansh of the Middle Ages. Ladino is therefore an artificially created written language that "only arises during the process of translating from Hebrew into Spanish [...]", ie an auxiliary language based on spoken Jewish Spanish and not a vernacular .

The basis of the word-for-word translations of the Hebrew holy scriptures is the obligation formulated in the Book of Deuteronomy not to change anything in the wording of the Bible text. If the Hebrew itself is not used, the translation should be as close as possible to the Hebrew original and transfer its particularities into the target language. It is believed that the Ladino was created in Spain in the 13th century to provide translations for Spanish Jews who did not understand sacred Hebrew. Ladino is closely based on the Hebrew text in syntax and choice of words. The aim was to reproduce the Hebrew text as precisely as possible, "in order to introduce the uneducated reader to the holy language via the national language and to give him an insight into the structure of Hebrew." This type of translation was often rejected against Spanish grammar in favor of Hebrew. A famous work is the Ferrara Bible, a translation of the Tanakh by using the Over Ladin driving that in 1553 Ferrara was printed. Over the centuries, Ladino also influenced the spoken language to a certain extent, but not the other way around.

In linguistics, the term calque language is also used for this ("traced language"). Calque languages were created from Hebrew for Greek, Italian, Arabic and Turkish, among others. Bible translations into German were also made using this method.

The Knesset , the Israeli parliament, prefers the name Ladino in the sense of Jewish Spanish. In 1996 it was decided to found the Autoridad Nasional del Ladino i su Kultura there .

Ladino is not to be confused with the Ladin language .

Djudezmo

(Also: Judezmo .) Derived from the Spanish word judaísmo , Djudezmo is originally the name of the non-Jewish neighbors of the Sephardi for the entirety of Jewish customs, outlooks on life, beliefs and the like. It is now also appearing as a term in linguistics, especially among American and Jewish researchers. This designation of the Sephardic language was widespread in Bulgaria, Macedonia and partly also in Greece and Romania.

In Turkey, the similar name djidió is common, derived from the Spanish word judío (Jew, Jewish).

Espanyol

(Also: Espanyolit, Spanyol, Spanyolit or Spaniolisch .) Especially in Turkey, this term is widespread where djidió is hardly or not in use. The term is derived from the Jewish Spanish word espanyol . In the form spanyol , it was the most widely used name of the Judeo-Spanish language in the old Jewish settlement areas in Palestine . The Jews there spoke mostly Jewish Spanish or Arabic before immigration from Eastern Europe began, which led to the emergence of a large, primarily Yiddish-speaking population group that was soon larger than the Palestinian Jews themselves. The forms ending in -it are the Hebrew names that go back to espanyol or spanyol .

Sephardic

(Also: Sefaradí , Sefardí or Sfaradí .) The term is not a name for the language used by the speakers themselves, but is used to distinguish the Sephardi from other ethnic subgroups of the Jewish people.

Hakitía

(Also: Hakitiya or Haketía .) As a name for the language of the Sephardic Jews, the term was used exclusively in northern Morocco. It is a separate dialect with essential differences to the Balkan Jewish Spanish. Therefore Hakitía is not a synonym of the above names. The term is derived from the Arabic words ḥakā 'to speak' or ḥekāiat 'story'.

Linguistics also uses the term Western Jewish Spanish when classifying the Jewish- Spanish dialects for Hakitía .

History and dissemination

Jews on the Iberian Peninsula before their deportation in 1492

Historians assume that the first Jews settled on the Iberian Peninsula as early as the 1st century BC , especially in the port cities of the Mediterranean coast. The oldest documentary evidence is a Jewish gravestone dated to the 2nd century of our time. It is known from written sources that in the 4th century the proportion of the Jewish population on the Iberian Peninsula was considerable.

The 10th and 11th centuries in Al-Andalus under the Caliphate of Cordoba were splendid times for Judaism . But the arrival of the Almoravids (1086–1147), who demanded conversion to Islam from those of different faiths, caused many Jews to flee, who then settled mainly in the Christian kingdoms of Castile-León , Aragon and Navarre . There the kings granted privileges to the Jewish settlements; the Jews paid duties and taxes in return.

With the exception of the Kingdom of Granada, the entire Iberian Peninsula had been recaptured by the Christians around the middle of the 13th century after almost half a millennium of Muslim rule. This was the best time of the Jews in the Christian kingdoms of their greatest prosperity in Castile and Aragon during the reign of Alfonso X . and Jaime I . The Jews lived in legal and communal independence, separated and independent of the Christian and Muslim citizenship.

Anti-Jewish propaganda in the second half of the 13th century culminated in 1391 in Seville with assaults against the Jewish community, which quickly spread. Within three months, around 50,000 of the 300,000 Jews were killed and entire communities destroyed. Many Jews were baptized or were forcibly baptized. The Jewish communities, which now mostly only existed in rural towns, became impoverished.

Origin of Jewish Spanish

Whether the Jews on the Iberian Peninsula already used a variety of their surrounding Romance languages in a comprehensive sense has not been established, but it can be assumed due to the existence of Jewish varieties of other languages. Certain deviations in vocabulary indicate this. According to this, there would have been Judeo- Castilian , Judeo- Aragonese , Judeo- Catalan and Judeo- Portuguese dialects, which differed slightly from the dialects of the Christian and Muslim population. “The fact that the Jewish-Spanish of the Ottoman Empire and the Haketía [in Morocco] z. Some of the innovations have in common [... and in addition, in both regions] the common loss of some words [can be ascertained ...] has so far been given too little attention, "emphasized the Romanist Gabinsky in 2011. Hebrew and Hebrew were often used to describe religious life Aramaic words, so that at least in this area of life the Jewish language usage differed from that of the Christian and Muslim population. The communal and legal independence of the Jewish communities should also have helped the development of a specifically Jewish vocabulary, especially in these areas.

Linguistic peculiarities of the Spanish of the Jews before 1492:

- own forms and arabisms to avoid typically Christian terms

- the word Dios (God) was changed to Dio , since the supposed plural ending -os contradicted the monotheistic belief

- the word domingo (Sunday) was not used due to the Christian background; instead, the term alhad , derived from the Arabic word, was usedالأحد al-ahad (the first; the first day of the week) goes back

- Hebraisms in the ethical field

- mazal 'star, star of destiny, destiny'

- kavod 'honor, glory'

- mamzer 'bastard'

- the verb meldar (Latin meletare 'to practice, to do something carefully') initially had the meaning of 'read religious texts'; in Jewish Spanish the verb took on the general meaning 'read, learn'

- Loan words from Arabic

- adefina 'buried'

- alarze 'cedar'

- Hebrew plurals also for some Spanish words

- ladroním next to ladrones 'thieves'

- Word formations with Hebrew words but Spanish suffixes or prefixes

- enheremar 'to ban'

- Hebrew suffixes for Spanish words too

- jsp. haraganud - Spanish haragán 'laziness'

The actual Jewish Spanish only developed after 1492, when the connection to the countries of the Iberian Peninsula was broken. After their expulsion, Judeo-Castilian, the Romance variety spoken by most Sephardic Jews, developed into an independent language that absorbed the other Judeo-Iberian varieties. In linguistics, the prevailing view today is that “Jewish Spanish is an independent - no longer Spanish - continuation of the Spanish language from the end of the 15th century.” It is more closely related to medieval Spanish than modern Spanish which took a different development.

Expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492

On March 31, 1492, the Catholic Kings Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon issued the Alhambra Decree in the course of the Christian reconquest . It contained the order for the complete expulsion within four months of those Jews from Castile, Leon and Aragon who did not want to be baptized. How many Jews left the country at that time cannot be precisely estimated; their number is estimated at 90,000 to 400,000.

Many of the Jews who stayed in Spain and converted to Christianity, so-called Marranos , later fell victim to the Inquisition because they were not considered credible Christians. This resulted in a wave of emigration by the Marranos, who then mostly accepted the Jewish faith again (especially in the 16th and 17th centuries).

In the Kingdom of Portugal, too, reprisals against subjects of Jewish descent increased. In the spring of 1506 at least 2,000 new Christians were murdered in Lisbon. This provoked a wave of refugees which, with the Inquisition that came into force in 1539, caused more Jews to emigrate; many of them had previously fled from Spain to Portugal because of the Alhambra Decree.

The destination of many emigrants was the Ottoman Empire of Sultan Bayezid II , who offered asylum to the displaced. The Ottoman Empire (Greece, Turkey, the Balkans, North Africa) wanted to participate in the European achievements in science and technology; therefore the Jews who fled from Spain were welcomed with open arms in the Ottoman Empire. The Sultan is said to have said: "How foolish are the Spanish kings that they expel their best citizens and leave them to their worst enemies." The newcomers were grateful and gladly put their qualifications in the service of their new homeland.

Outside of the Ottoman Empire, the refugees initially turned to Portugal, as well as Morocco, Italy and Northern Europe - France, England, Germany and the Netherlands. In northern Morocco, the Sephardi were numerically in the minority compared to the Arab and Berber-speaking Jewish population. Nevertheless, the Spanish or Jewish Spanish could hold up there. Moroccan Jewish Spanish is known under the name Hakitía and lexically strongly influenced by Arabic. The Sephardi, who fled to Italy, quickly gave up their Spanish language in their closely related linguistic milieu. The Sephardi who fled to Northern Europe also adapted more quickly to the respective national language. From the 17th century onwards, mainly Marranos came to the Netherlands and returned to their original beliefs.

The expulsion decree of 1492 was repealed in 1924. Today there are Jewish communities in Spain again.

Spread of Jewish Spanish

Even before the arrival of the Sephardi in the Ottoman Empire , Jews lived there, especially Romani people who spoke Greek , and a small number of Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi . In the neighboring Arab countries, the Jews spoke Arabic. The newly arrived refugees spoke various Ibero-Romance varieties, especially Castilian , Catalan and Aragonese ; later Portuguese- speaking Sephardi also came to the Ottoman Empire.

A political basis of the Ottoman Empire was the Millet system , i. H. the population lived in independent religious communities, the Millet communities. In this respect, the Ottoman state did not define itself as a homogenizing nation-state, but as a multi-ethnic "multi-ethnic state" that guaranteed the communities the protection of life and property as well as the free practice of religion and allowed them to organize independently. The Millet system ensured that the minorities could retain their cultural and linguistic characteristics. This was true for the Jewish minority as well as for the Christian minorities. This demarcation and the resulting concentration in a separate social milieu with its own cultural institutions led the Sephardim to form a collective identity; A strong social cohesion ensured an unhindered and free community life within which customs, traditions, language and religion could develop.

The fact that the newcomers prevailed linguistically in the main centers of the Ottoman Empire, in Constantinople ( Istanbul ) and Saloniki ( Thessaloniki ), was not only due to their numerical but also their cultural superiority. The Castilian Sephardi assimilated the other Jews of Iberian origin (Catalans, Aragonese, Portuguese), and a separate, predominantly Castilian Sephardic Koine developed , the Jewish-Spanish. “So Jewish Spanish is the continuation of the Jewish variety of Spanish from the end of the 15th century, which in the following period developed in isolation and separately from the Spanish language.” In addition, the Sephardic language played an important role in the 16th century as a means of communication between different ethnic groups, especially as a commercial language in the Eastern Mediterranean. In addition, Jewish Spanish in general retained its position not only as the language of everyday life, but also as the language of instruction, literature and the press in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Thanks to a number of factors, Jewish Spanish remained stable from the 16th to the 19th centuries. Lucrative economic conditions for Jewish craftsmen and merchants contributed to this, as did the Sephardization of the majority of the rest of the Jews, so that within the Jewish population of the Ottoman Empire there was soon a cultural homogeneity on a religious and linguistic basis, which was due to the unimpeded connection between the communities within one large state structure was given wings. Essential factors were also the sense of community of the Sephardi, the solidarity of the residents of the Jewish quarters with one another and their limited contact with the outside world, with the Jewish population specializing in a few branches of business.

Decline in Jewish Spanish

At the beginning of the 19th century the political situation in the Ottoman Empire changed and caused the decline of Jewish Spanish. Essential factors were industrialization and the associated decline of Jewish handicrafts as well as the emergence of a new bourgeois class that no longer defined itself ethnically but nationally and gave up its traditional cultural heritage.

The Edict of Gülhane of 1839 marked a turning point for the entire Ottoman society. The reforms (Tanzimat) aimed to modernize the country, the most important requirement being the strengthening of the central power. France served as a model. But the realignment changed not only the structure of the state, but also the education and language policy. The religious communities that have so far served the various population groups as generators of identification should step back behind the state institutions.

Some sections of the population succeeded in breaking away from the Ottoman Empire; they formed independent states ( Greece - 1830 with the exception of Salonika - 1913; Serbia - 1867; Bulgaria - 1878; Sarajevo - 1878; Romania - 1878). This changed the living environment of the Sephardi permanently, because now the Sephardic communities once united in a large empire belonged to different national states and were confronted with their minority politics. Lessons in the respective national language became compulsory everywhere.

As a result of these measures and the loss of traditional ways of life, Jewish Spanish was often given up in favor of the national languages Turkish , Greek , Bulgarian and Serbo-Croatian at the beginning of the 20th century . For example, in the censuses of Turkey in 1935 and 1955, almost 72% of the Jews surveyed stated Jewish Spanish as their mother tongue, whereas in the 1965 census only around 32% said they were native speakers and 18% named Jewish Spanish as a second language. In addition, the use of Jewish Spanish had withdrawn from the public to the private sector, to the family.

Meanwhile, the Spanish-speaking Jews resident in North Africa, after contact with the Spanish colonial power from 1860 onwards, very quickly adapted Jewish Spanish to Iberian Spanish. The variety known as Haketiya, which had gone its own way since the 18th century and separated from the Southeastern European variety Djudezmo, disappeared faster than the Djudezmo in the eastern Mediterranean, so that the mass immigration of Maghrebian Jews to Israel no longer strengthened the Jewish-Spanish-speaking population there .

German National Socialism also contributed in particular to the decline in Jewish Spanish. During the Shoah , Jewish-Spanish speaking Jews were persecuted and murdered like all other Jews, especially in the German-occupied countries such as Greece and Yugoslavia. In cities like Saloniki, in which the majority of Jewish Spanish was spoken in the past, or in the Sephardic communities of the Balkans, very few Sephardi still live today.

Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU)

The Alliance Israélite Universelle, founded in Paris in 1860, had a major influence on the development of Jewish Spanish . The founders of the AIU, Jewish intellectuals, strived for the emancipation and equality of the Jews and wanted to work for the rights of Jews worldwide. The aim was to improve the position of the Jews through modern Western upbringing and education.

Because of France's great influence in the Ottoman Empire, the AIU's engagement faced few bureaucratic obstacles. In 1910, 116 schools of the AIU were already active in the Ottoman Empire and Morocco. However, from 1920 to 1930 they were nationalized in Turkey, Greece and Macedonia .

Since the dissemination of the French language and culture played an important role in the schools of the AIU, classes were held in French almost everywhere. On the one hand, the AIU made a major contribution to the formation of the Sephardi, on the other hand, it pushed Jewish-Spanish into the family sphere. French was the language of the educated, Jewish Spanish was declassified to jargon and pushed into the background.

Amsterdam, Bordeaux, London, Emden and Altona: the northern diaspora of the Sephardi

It is noteworthy that the Spanish and Portuguese of the Conversos who emigrated from the Iberian Peninsula in the centuries after 1492 (see map) (i.e. Jews who converted to Christianity and their descendants who returned to Judaism in their new places of residence) do not differ significantly from the respective language forms of Iberian Peninsula developed. The transition from medieval to modern Spanish had already taken place, so that the typical sound of Djudeo-Espanyol, which distinguishes it from modern Spanish (for characteristics of Jewish Spanish see below), cannot be determined here. The Conversos already brought modern Spanish with them to Northern Europe. The writings of the Sephardic community in Amsterdam are also written in Spanish (and Portuguese) and not in Djudeo-Espanyol, which was only distributed in the Mediterranean and the Balkans, where the cultural ties between the Sephardic Jews and the countries of the Iberian Peninsula were broken.

Situation today and imminent death by speech

A Spanish survey from 1922 numbered 80,000 Hispanophones for Saloniki, 24,000 for Belgrade, 30,000 for Bucharest, 10,000 for Cairo, 6,000 for Alexandria and 50,000 for Bulgaria, but these figures are probably too optimistic, writes Armin Hetzer in his textbook Sephardic from the year 2001. An estimate from 1966 states that there are 360,000 speakers of Jewish Spanish worldwide, of which 300,000 in Israel, 20,000 in Turkey, 15,000 in the USA and 5,000 in Greece. In 2012, a leading researcher of Jewish-Spanish history and traditions, Michael Studemund-Halévy , estimated in an interview with the taz that there were only around 25,000 speakers worldwide. As a result, 22,000 Sephardi live in Turkey, but only 600 to 800 of them speak Jewish Spanish; In Bulgaria, out of 3,000 Sephardi, 250 to 300 are still speakers of Jewish Spanish. In Serbia there are two speakers, in Slovenia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia and Greece only a few, but larger groups of speakers in Paris, London, the USA and Israel. Taking into account the 1966 figures, the number of speakers in Israel today is likely to be around 20,000. Studemund-Halévy suspects that in the next generation, Jewish-Spanish will only be memories. However, there are also more optimistic estimates; J. Leclerc assumed in 2005 about 110,000 speakers, of whom about 100,000 lived in Israel.

Despite the decline in the number of speakers, efforts are being made to keep the language and culture of the Sephardic Jews alive. It is worth mentioning, among other things, two periodicals kept exclusively in Jewish Spanish. El Amaneser appears monthly in Istanbul and is published by the Sentro De Investigasiones Sovre La Kultura Sefardi Otomana-Turka . The magazine Aki Yerushalayim appeared 1980-2017 twice a year in print in Jerusalem, but will continue to exist as an online edition. In New York, the Foundation for the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture, FASSAC, is trying to save the culture of Sephardic Jews from oblivion. Sephardic communities also exist in Latin America. There is a very active community in Buenos Aires in particular, which publishes a monthly independent magazine in Spanish and Jewish Spanish. On the Israeli state radio there is a one-hour weekly broadcast in Jewish Spanish.

Three universities in Israel currently offer special programs for studying Jewish Spanish; there is also - unique in Europe - u. a. a master’s program in Paris, which combines the study of Jewish-Spanish language, literature and culture with that of other Jewish languages and cultures, as well as courses at other universities (e.g. in Marseille and Frankfurt am Main in the context of the subject Hebrew or Jewish studies , also in Hamburg, Tübingen and Basel in the context of Romance studies as well as in Madrid and the USA).

Dialects

Due to the extensive distribution area, different dialects have developed. The dialects of the Balkans (Oriental Jewish Spanish) are influenced by Turkish and Greek, the North African dialects (Western Jewish Spanish or Hakitía) by Arabic.

Oriental Jewish Spanish

The oriental Jewish-Spanish is divided into a southern and a northern variety, the northern in turn into a northwestern (former Yugoslavia ) and a northeastern (Romania and Bulgaria except for the coastal strip). The southern group includes the southern Balkans including Salonika and Istanbul as well as all of Turkey and eastern Bulgaria. Saloniki and its hinterland form a separate dialect zone.

Western Jewish Spanish (Hakitía)

Western Jewish Spanish was influenced by Arabic primarily on the lexical level. The greatest differences to oriental Jewish Spanish can be found in the vocabulary. Arabic had little influence on grammatical structures.

Basically, Western Jewish Spanish was closer to the standard Spanish language, as Spaniards lived in various cities on the coast of North Africa ( Ceuta , Melilla , Oran , Tangier , Asilah , Larache ) and Spain conquered northern Morocco in 1860 and managed it as a colony from then on. The latter in particular influenced the status of Jewish Spanish in this area. The higher a person rose on the social ladder, the less they used typical Jewish Spanish expressions; in fact, arabisms were almost entirely given up. Young people in particular only spoke in the family or in the Hakitía community. In this way, Moroccan Jewish-Spanish gradually approached standard Spanish.

The reputation of the Hakitía only began to change in Israel in the 1980s. Since the cultural and ethnic diversity of the Jewish people was now recognized as enriching, Hakitía was again understood for the first time as an autonomous language and a valuable cultural asset.

Jewish Spanish as a written language

Originally, Jewish Spanish was written using Hebrew letters. Both the so-called Raschi script and the traditional square script were used as block letters . The Raschidruck always appeared without vowel markings, the square script was mainly used to print headings and religious texts with the Masoretic vowel marks. These two fonts were mainly used in the major publishing houses Saloniki and Constantinople, while the majority of Sephardic Moroccan literature appeared in the handwritten variant of the Rashi script, the solitreo or soletero style (also letra de carta, letras españolas or Judezmo ) since there was a lack of publishers for Jewish-Spanish literature. As early as the 16th century there were some texts printed with Latin letters.

Books and magazines printed in Rashi script were easily read and understood in the various regions of the Ottoman Empire, despite different dialects and different pronunciations of Jewish Spanish.

The modernization and social upheaval in the Ottoman Empire also influenced the life of the Sephardic Jews. The desire to adapt to modern society promoted the examination of the Jewish-Spanish culture. In this context, from the end of the 19th century, newspapers also discussed the Jewish-Spanish language and its writing. The spelling developed into a central topic in the debates of the Sephardic intellectuals, promoted by the AIU and by the Turkish spelling in Latin letters, which was implemented by Kemal Ataturk after the establishment of the Republic of Turkey (1923) . The background of the discussion was also the poor reputation of Jewish Spanish, the lack of uniform linguistic standards and the fact that Jewish Spanish was a Romance language, which suggested the use of the Latin script. Luzero de la Paciencia by Turnu Severin, in Romania, was the first Jewish-Spanish newspaper to use Latin characters from 1887. The magazine Şalom was printed in Latin letters right from the start (1947).

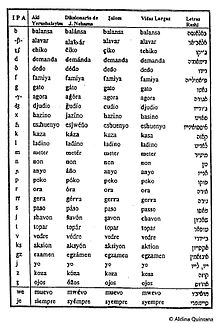

The aim of the debate was to develop an orthography with Latin letters that would take into account the phonetics of Jewish Spanish. Editors of various newspapers worked out new graphics of Jewish Spanish which existed side by side and in some cases still exist. The best known are the graphics of the magazines Aki Yerushalayim (Israel) and Şalom (Turkey), the graphics based on the Dictionnaire du judéo-espagnol (Madrid, 1977) by Joseph Nehama and the French-oriented graphics of the Association Vidas Largas (France). Since no uniform, stable norms have been developed for a long time, as no language academy established fixed rules for Jewish Spanish, various orthographic systems still exist today, which are mostly based on the surrounding languages. Depending on the place and medium , the word noche is written noche (Aki Yerushalayim), notche (Vidas Largas) or noçe (Şalom).

It took “... - after 1992 - around eight years until the Sephardi, after heated discussions, agreed on an approximately uniform and, above all, systematic spelling of their language, following the model of the Aki Yerushalayim magazine published by Moshe Shaul . There are still no normative bodies, but the intention is already well on the way to being implemented. "

Characteristics of Jewish Spanish

Jewish Spanish is an Ibero-Romance language and is so closely related to Spanish that mutual understanding is usually easy. Syntax, phonology, morphology and lexicons are based in many respects on Spanish from the late 15th and early 16th centuries. In addition, there are own innovations and a large number of elements and loan words from the surrounding languages. The differentiation between Jewish Spanish and Spanish was evident from around the beginning of the 17th century.

Jewish Spanish is usually written without accents. This applies above all to the Aki Yerushalayim spelling . Exceptions are made in cases where one might be inclined to shift the stress point to another syllable.

The following description of the language features also refers to the graphics of Jewish Spanish in the Aki Yerushalayim magazine published by Moshe Shaul .

Jewish Spanish Alphabet ( Aki Yerushalayim )

| Letter | IPA | Example Jewish Spanish (jsp.) |

translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. | [a] | agora | now |

| B. | [b] | biervo | word |

| CH | [tʃ] | chiko | small |

| D. | [d] | devda | fault |

| DJ | [dʒ] | djudió | Jewish |

| E. | [ɛ] or [e] | ermuera | daughter in law |

| F. | [f] | fierro | iron |

| G | [G] | guevo | egg |

| H | [x] | hazino | ill |

| I. | [i] | inyeto | grandson |

| J | [ʒ] | vijitar | visit |

| K | [k] | content | satisfied |

| L. | [l] | lingua | language |

| M. | [m] | reportable | read |

| N | [n] | negro | bad |

| NY | [ɲ] | espanyol | Spanish |

| O | [O] | orozo | happy |

| P | [p] | preto | black |

| R. | [r] | reushir | success |

| S. | [s] | somportar | bear |

| SH | [ʃ] | shukur; bushkar | thank you; search |

| T | [t] | topar | Find |

| U | [u] | umo | smoke |

| V | [β] | vava | grandmother |

| X | [gz] | exemplo | example |

| Y | [j] | yelado | cold |

| Z | [z] | zirguela | plum |

phonetics

The vowels are like in Spanish a, e, i, o, u . Differences to today's Spanish are particularly noticeable in the diphthongization .

- jsp. pueder - span. poder 'can';

- jsp. buendad - Spanish bondad 'goodness';

- jsp. adientro - Spanish adentro 'inside, in'

- jsp. Vierbo - span. verbo 'verb'

- jsp. kero - span. quiero 'I want'

- jsp. penso - Spanish pienso 'I think'.

In the consonant system it is noticeable that the Jewish Spanish did not undergo the Castilian disonorization , Spanish reajuste de las sibilantes del idioma español , which only took place after the expulsion of the Sephardic Jews towards the end of the 16th century in Spain. For example, words like abajo , mujer or gente , which are pronounced with the velar [x] in today's Spanish , retained the old Spanish palatal pronunciation of [ʃ], [und] and [dʒ] in Jewish Spanish . In Jewish Spanish, the sound [ʃ] is usually written with -sh-:

- jsp. abasho - Spanish abajo 'below'

- jsp. deshar - span. dejar 'to let'

- jsp. pasharo - Spanish pájaro 'bird'

- jsp. bushkar - Spanish buscar 'to search'.

A relic from Old Spanish is the initial f- as in fierro (Spanish hierro 'iron' or ferir (Spanish herir 'injure, damage')), but this preservation is not generally Jewish-Spanish, but regionally limited. The opposition / b / (occlusive) and / v / ( fricative , realization regionally different [v] or [β]), which are homophonic in New Spanish, was also retained .

Innovations in the phonetic area of Jewish Spanish are as follows:

- Transition from nue- to mue-: jsp. muevo - Spanish nuevo 'new'; jsp. muez - span. nuez 'nut'

- Transition from sue- to eshue-, esfue-: jsp. es.huenyo - span. sueño 'dream, sleep'

- Transition from -iu- to -iv-: jsp. sivdad - Spanish ciudad 'city'; jsp. bivda - span. viuda 'widow'

- Yeísmo: jsp. yamar - Spanish llamar 'to call'; jsp. maraviya - span. maravilla 'the magnificent'

- Elimination of [j] after -i- or -e-: jsp. amario - Spanish amarillo 'yellow'; jsp. akeo - Spanish aquello 'that'

- Metathesis -rd- to -dr-: jsp. vedre - Spanish verde 'green'; jsp. tadre - span. tarde 'late'.

morphology

The Jude-Spanish morphology largely corresponds to today's standard Spanish. Some key differences are:

- different gender of some nouns: jsp. la azeta - Spanish el aceite 'the oil'; jsp. la onor - Spanish el honor 'the honor'; jsp. la tema - span. el tema 'the subject'; jsp. la idioma - span. el idioma 'the language'

- Gender marking of nouns - -o, -a instead of -e : jsp. la klasa - Spanish la clase 'the class'; jsp. la fraza - Spanish la frase 'the sentence'; jsp. la katastrofa - Spanish la catástrofe 'the catastrophe'; jsp. el atako - Spanish el ataque 'the attack'

- Adjectives are usually given a gender mark in the feminine: una situasion paradoksala , la revista kulturala

- the perfect (span. preterito perfecto ) does not exist in Jewish-Spanish

- the compound past (pasado kompozado) is formed with tener as an auxiliary verb

- In the past tense (pasado semple) the 1st Ps.Sg. + Pl. of the verbs of the a-conjugation in -i, -imos : (f) avlar, (f) avl i , (f) avl imos (Spanish. hablar, habl é , habl amos ).

Examples of regular verb conjugation:

Present:

| -ar verbs yevar 'carry, take away' |

-er verbs komer 'eat' |

-ir verbs suvir 'lift up, go up' |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| yo | yevo | komo | suvo |

| do | yevas | komes | suves |

| el, eya | yeva | come | suve |

| mozotros | yevamos | comemos | suvimos |

| vosotros, vozotras | yevásh | komésh | suvísh |

| eyos, eyas | yevan | come | suven |

Preterite:

| -ar verbs yevar 'carry, take away' |

-er verbs komer 'eat' |

-ir verbs suvir 'lift up, go up' |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| yo | yeví | komí | suví |

| do | yevates | committee | suvites |

| el, eya | yevó | komió | suvío |

| mozotros | yevimos | komimos | suvimos |

| vosotros, vozotras | yevátesh | komitesh | suvitesh |

| eyos, eyas | yevaron | komieron | suvieron |

syntax

Basically, the Judean Spanish syntax corresponds to the Spanish, i.e. SVO word order, pronouns and numerical words come before the relational word, adjectives and genitive attributes are after the relational word. The most typical innovations in Jewish Spanish are the Balkan constructions with the subjunctive instead of the infinitive:

- jsp. Ke ke aga? - span. ¿Qué quiere (s) que haga? 'What should I do?', Jsp. kale ke aga - spanish tengo que hacer 'I have to do'.

Lexicons

A significant part of the basic Spanish vocabulary of the 15th century, which is well preserved in Spain to this day, has been preserved. As a result, communication between speakers of both languages is possible without any problems. It is easier for Spanish speakers to understand, as Jewish Spanish often contains only one or two of a large number of synonyms.

- span. nunca and jamás 'never' - jsp. just nunka

- span. empezar, comenzar and principiar 'to begin' - jsp. only empesar and prisipiar

There are a number of Jewish Spanish words that differ greatly in their meaning from modern Spanish:

- atravesar jsp. 'vomit' - span. 'measure something through, traverse'

- boda jsp: 'holiday' - span. 'wedding'

- sakudir jsp. 'clean' - span. sacudir 'shake, shake'.

On the other hand, meanings from Old Spanish have been preserved for many words that modern Spanish no longer knows:

- afeitar jsp. 'put in order' - span. 'shave'.

Even more numerous are the words that have not only been preserved from Old Spanish in terms of their meaning but also of their form:

- jsp. agora - span. ahora 'now';

- jsp. estonses - span. entonces 'then';

- jsp. solombra - Spanish sombra 'shadow'.

Innovations that use typical elements of Spanish can be found in the area of word formation:

- Derivations on -edad: jsp. derechedad , djustedad - span. justicia 'justice'; jsp. provedad - span. pobreza 'poverty'

- Derivatives on -és: jsp. chikés - spanish infancia, niñez 'childhood; jsp. muchachés - Spanish juventud 'youth'.

It is noticeable that Jewish-Spanish preserved only a few Arabicisms from the Hispanic period. In addition, entire parts of the vocabulary were given up (especially in the field of fauna and flora) and new ones were created, such as the names of birds. The general terms ave and pasharó (Spanish ave 'bird, poultry'; pájaro 'bird, little bird') have been retained, the other bird names are borrowed:

- jsp. bilbiliko - Spanish ruiseñor - Turkish bülbül 'nightingale'.

In addition, Jewish Spanish has many words from Hebrew that are often related to religion. Linguistic contact with the surrounding languages results in lexical influences from Turkish and, to a lesser extent, Italian; Influences of French can be traced back to the role of AIU. Greek, Slavic and Romanian influences were mostly limited to the regional area. The Portuguese-speaking Sephardi, who settled in the eastern Mediterranean after their expulsion from Portugal, also influenced the lexicons of Jewish Spanish.

- Hebraisms: ganéden 'Paradise, Garden of Eden'; sedaká 'alms, charity'

- Turkisms: adjidearse de 'to have pity on'; djomerto 'generous'

- Gallicisms : banker 'banker'; matmazel ~ madmuazel 'Mademoiselle'; regretar 'regret'

- Italianisms: adío 'adieu, bye'; lavoro 'work'; nona 'grandmother'.

- Lusitanisms : chapeo 'hat'; kalmo 'calm'; malfadado 'mishap'

Text example

"LAS KONSEJAS I LOS KUENTOS POPULARES DJUDEO-ESPANYOLES"

"Ke azian muestros padres en los tiempos ke no avia ni radio ni televizion i ke el uzo de los sefaradis era de pasar la noche adientro de kaza, kon la famiya o kon los vizinos? Uno de los divertimientos los mas populares de akeyos tiempos era el de sintir las narasiones de kuentos i konsejas. Sovre todo en las largas noches de invierno, kuando eskuresia bien presto i toda la famiya estava en kaza, arekojida al deredor del 'tandur', del brazero, ke plazer era de eskuchar los kuentos i las konsejas sovre las fantastikas aventuras de prinsipes o kavipes barraganes, o de mansevos proves ma intelijentes i korajozos, ke kombatiendo contra dragos i leones, o contra ichizeras i reyes krueles, riushian siempre a salvar a sus keridos ia yegar a porto a salvo, malgrado todas las difikultades i todos los pelentavan . "

Audio samples

The following audio examples of Jewish Spanish are from the Ladinokomunita website.

- Audio sample 1 (MP3 file; 390 kB)

- Audio sample 2 (MP3 file; 364 kB)

Language comparison Jewish Spanish - Spanish

Jews Spanish El djudeo-espanyol, djidio o djudezmo es la lingua favlada por los Sephardim, djudios arrondjados de la Espanya Enel 1492. It una lingua derivada del kastilyano i favlada por 25.000 personas en komunitas en Israel, la Turkiya, antika Yugoslavia, la Gresia, el Morocco, Mayorka i las America, entre munchos otros.

Spanish El judeo-español, djudio o djudezmo es la lengua hablada por los sefardíes, judíos expulsados de España en 1492. Es una lengua derivada del castellano y hablada por 25,000 personas en comunidades en Israel, Turquía, la antigua Yugoslavia, Grecia, Marruecos, Mallorca y las Americas, entre muchos otros.

German Judenspanisch, Djudio or Djudezmo is the spoken language of the Sephardi, Jews who were expelled from Spain in 1492. It is a language derived from Spanish and is spoken by 25,000 people in communities, including Israel, Turkey, the former Yugoslavia, Greece, Morocco, Mallorca, America.

See also

literature

- Johannes Kramer : Jewish Spanish in Israel. In: Sandra Herling, Carolin Patzelt (ed.): World language Spanish. ibidem-Verlag, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-89821-972-3 , pp. 291-310.

- Tamar Alexander: El klavo de Djoha 'El Kantoniko de Haketia' en la revista Aki Yerushalayim. In: Pablo Martín Asuero / Karen Gerson Şarhon: Ayer y hoy de la prensa en judeoespañol. Actas del simposio organizado por el Insituto Cervantes de Estambul en colaboración con el Sentro de Investigasiones Sovre la Cultura Sefardi Otomana Turka los días 29 and 30 de April 2006. Editorial Isis, Istanbul 2007, pp. 97-105.

- Anonymous (o. A.): Las konsejas i los kuentos populares djudeo-espanyoles. [1] , accessed October 3, 2012.

- Barme, Stefan (2004): Syntactic Gallicisms in modern Southeast European Jewish Spanish. In: Busse, Winfried (ed.): Judenspanisch VIII. Neue Romania 31 . Berlin: Institute for Romance Philology, pp. 73–91.

- Bitzer, Annette (1998): Jews in Medieval Hispania. History, cultural achievement, language. In: Busse, Winfried (Ed.): Judenspanisch III. New Romania 21 . Berlin: Institute for Romance Philology, pp. 7–150

- Studemund-Halévy, Michael (2014): La Boz de Bulgaria. Barcelona.

- Studemund-Halévy, Michael et al. (2013): Sefarad on the Danube. Barcelona.

- Bossong, Georg (2008): The Sephardi. History and Culture of the Spanish Jews . Hamburg: Beck.

- Busse, Winfried (1991): On the problematic of Jewish Spanish. In: Busse, Winfried (Ed.): Judenspanisch I. Neue Romania 12 . Berlin: Institute for Romance Philology, pp. 37–84.

- Busse, Winfried (1999): The language (s) of the Sephardi: Ladino, Ladino. In: Rehrmann, Norbert / Koechert, Andreas (ed.): Spain and the Sephardi. History, culture, literature. Romania Judaica Volume 3. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer, pp. 133-143.

- Busse, Winfried (2003): Judeo-Spanish writing systems in Roman letters and the normalization of orthography. In: Busse, Winfried (Ed.): Judenspanisch VII. Neue Romania 28 . Berlin: Institute for Romance Philology, pp. 105–128.

- Busse, Winfried (2011): Brief Characteristics of Jewish Spanish. In: Busse, Winfried (Ed.): Judenspanisch XIII. New Romania 40 . Berlin: Institute for Romance Philology, pp. 171–196.

- Busse, Winfried / Kohring, Heinrich (2011): Foreword to / in Gabinskij, Mark A .: The Sephardic Language . Tübingen: Stauffenberg, pp. 7–9

- Busse, Winfried / Studemund-Halévy, Michael (eds.) (2011): Lexicologia y lexicografía judeoespañolas . Peter Lang, Bern

- Diaz-Mas, Paloma (1992): Sephardim. The jews from Spain . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Fintz Altabé, David (2003): Reflexiones sobre la grafía del judeo-español. In: Busse, Winfried (Ed.): Judenspanisch VII. Neue Romania 28 . Berlin: Institute for Romance Philology, pp. 59–85.

- Gabinskij, Mark A. (2011): The Sephardic Language . Tübingen: Stauffenberg.

- Christoph Gabriel, Susann Fischer and Elena Kireva: Jewish Spanish in Bulgaria. A diaspora language between archaism and innovation. In: Doerte Bischoff, Christoph Gabriel, Esther Kilchmann (Eds.): Language (s) in Exile. (Jahrbuch Exilforschung 32) Edition Text + Critique, Munich, pp. 150–167

- Gerson Sarhon, Karen (2004): Judeo-Spanish: Where we are, and where we are going. [2] >, accessed March 18, 2013

- Hetzer, Armin (2001): Sephardic: Introduction to the colloquial language of the Southeast European Jews . Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Kramer, Johannes / Kowallik, Sabine (1994): Introduction to the Hebrew script . Hamburg: Buske.

- Kowallik, Sabine (1998): Contributions to the Ladino and its history of orthography . Tübingen: Buske.

- Liebl, Christian (2007): Early recordings of Judeo-Spanish in the Phonogrammarchiv of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. In: Busse, Winfried (Ed.): Judenspanisch XI. New Romania 37 . Berlin: Institute for Romance Philology, pp. 7–26.

- Overbeck de Sumi, Ruth (2005): Urtext and translation of the Hebrew Bible in Sephardic Judaism. A linguistic analysis of Ladino versions of the Book of Ruth . In: Busse, Winfried (Ed.): Judenspanisch IX. New Romania 34 . Berlin: Institute for Romance Philology, pp. 109–216.

- Platikanova, Slava (2011): Jacques Loria. Dreyfus I. In: Busse, Winfried (Hrsg.): Judenspanisch XIII. New Romania 40 . Berlin: Institute for Romance Philology, pp. 109–133.

- Esther Sarah Rosenkranz: The Sociolinguistic Development of Sephardic in the Diaspora - with special consideration of the development in Israel. Diploma thesis, University of Vienna, Vienna 2010

- Quintana Rodríguez, Aldina (2004): El sustrato y el adstrato portugueses en judeo-español. In: Busse, Winfried (ed.): Judenspanisch VIII. Neue Romania 31 . Berlin: Institute for Romance Philology, pp. 167–192.

- Quintana Rodríguez, Aldina (2006): Sephardica. Geografía Lingüística del Judeoespañol . Peter Lang, Bern.

- Şahin Reis, Seminur (2005): The Sephardi in the Ottoman Empire and in Turkey since 1839. In: Busse, Winfried (ed.): Judenspanisch IX. New Romania 33 . Berlin: Institute for Romance Philology, pp. 217–259.

- Socolovsky, Jerome (2007): Lost Language of Ladino Revived in Spain. [3] , accessed February 21, 2013.

- Studemund-Halévy , Michael (2012): A fabulous world. [4] , accessed September 27, 2012.

- Transversal magazine , issue 2 , volume 13: Focus on Sefarad in Austria-Hungary. Journal of the Center for Jewish Studies, University of Graz . Studienverlag, Innsbruck 2012 (three articles on the Sefarad in Sarajevo, in Bosnia, on Baruch Mitrani in Vienna and on the Balkans, pp. 9–80).

- Varol, Marie-Christine (2003): Normalización grafica del judeoespañol: ¿Por qué? y ¿Para quién? In: Busse, Winfried (Ed.): Judenspanisch VII. Neue Romania 28 . Berlin: Institute for Romance Philology, pp. 87-104.

- Varol, Marie-Christine (2008): Manual of Judeo-Spanish. Language and Culture . Bethesda: University Press of Maryland.

Web links

- Jewisch Language Research website

- about Jewish Spanish at Orbis Latinus

- Phonogram archive in Vienna, Austria

- Ladinokomunita

- Ottoman-Turkish Sephardic Culture Research Center

- Society for Sephardic Studies in Jerusalem, Israel

- Center for Ladino in Israel

- The Sephardic singer Yasmin Levy

- Ladinokomunita.

Newspapers and magazines:

- Aki Yerushalayim : Israeli culture magazine in Jewish Spanish

- Şalom : in Istanbul, Turkey, newspaper of the Sephardic Jews with articles also in Jewish Spanish

- El Amaneser : monthly Jewish- Spanish supplement to the newspaper Şalom , published by the Ottoman-Turkish Sephardic Culture Research Center

- Sefaraires : monthly, independent publication of the Sephardic community in Buenos Aires, Argentina

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 24

- ↑ Sephardi are those Jews whose ancestors lived in Spain until their expulsion in 1492 ( Decreto de la Alhambra ) or in Portugal until 1497 , as well as descendants of Jews who converted to Christianity, who remained on the Iberian Peninsula after the expulsion of the Jews and later because of them emigrated from persecution and converted back to Judaism. The latter were not involved in the development of the Judeo-Spanish language, as their places of refuge (France, England, Holland, Northern Germany) were not in the settlement areas of the Judeo-Spanish-speaking communities ( Ottoman Empire , Morocco).

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 23

- ↑ Bitzer 1998: 120

- ↑ Busse 1991: 42

- ^ Overbeck 2005: 117

- ^ Overbeck 2005: 115

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 17f

- ^ Overbeck 2005: 144

- ^ Overbeck 2005: 134

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 18f

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 18

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 25

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 20

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 20

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 21

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 21

- ↑ Alexander 2007: 97

- ↑ Alexander 2007: 99

- ↑ Bitzer 1998: 15-18

- ↑ Bitzer 1998: 25

- ↑ Bitzer 1998: 32

- ↑ Bitzer 1998: 25

- ↑ Bitzer 1998: 44

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 44

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 43–44

- ↑ Bitzer 1998: 126-127

- ↑ Bitzer 1998: 121

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 14

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 13

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 36

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 16

- ↑ Quintana 2004: 168-169

- ↑ Bossing 2008: 57

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 38

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 16

- ↑ Barme 2004: 73

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 34

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 37

- ↑ Şahin Reis 2005: 217-219

- ↑ Şahin Reis 2005: 224

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 37

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 14

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 40

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 41

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 41

- ↑ Platikanova 2011: 113

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 41

- ^ Kramer / Kowallik 1994: XV

- ^ Şahin Reis 2005: 243

- ^ Hetzer 2001: VI

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 42f

- ↑ Platikanova 2011: 120

- ↑ Platikanova 2011: 121

- ↑ Platikanova 2011: 122

- ^ Hetzer 2001: VI

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 27

- ↑ taz

- ↑ Studemund-Halévy 2012

- ↑ http://www.ethnologue.com/language/lad

- ↑ Eltster dzhudezme-zhurnal shlist printed nusekh. In: Forverts , March 2017, p. 35.

- ↑ https://www.kan.org.il/tv-guide/#stations_kanTarbut

- ↑ http://www.inalco.fr/langue/judeo-espagnol

- ↑ https://www.uni-frankfurt.de/42965714/Studieng%C3%A4nge

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento of the original from May 26, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed October 3, 2012

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 54

- ↑ Alexander 2007: 99f

- ↑ Alexander 2007: 100

- ↑ Alexander 2007: 100f

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 20

- ↑ Fintz Altabé 2003: 59

- ↑ Busse 2003: 112

- ↑ Busse 2003: 116

- ↑ Fintz Altabé 2003: 60

- ↑ Busse / Kohring 2011: 8

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 49

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 47

- ↑ Busse 2011: 171

- ↑ Armin Hetzer: Sephardic: Judeo-español, Djudezmo. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2001, ISBN 3-447-04465-9

- ↑ Busse 2003: 115

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 85f

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 95f

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 46f

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 49

- ↑ Busse 2011: 174-177

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 46

- ↑ Busse 2011: 177-180

- ↑ Gabinskij 2011: 108 and 135

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 113

- ↑ Gabinskij 2011: 146ff

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 50

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 165ff

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 168f

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 169

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 169f

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 51

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 51

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 47

- ↑ Barme 2004: 81

- ^ Quintana 2004: 178

- ↑ Gabinsky 2011: 172-175

- ↑ Quintana 2004: 183-187

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento of the original dated December 14, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.